Today, America stands at a critical crossroads, with divisions more palpable and intense than anything we’ve seen in decades. This division extends far beyond politics—it infiltrates daily life, shapes policy, and threatens our collective sense of security, belonging, safety, and identity. The recent 2024 presidential election marks a defining moment in American history, underscoring the critical era we are living in. As young people, we are the future. We have inherited a seemingly irreparable system that is, and will remain, our responsibility to reshape. We must come together to face these challenges with unity and hope. Faded Glory is our reflection of this responsibility; it is our analysis of a moment in time in which our nation’s ideals feel more like fantasy than reality.

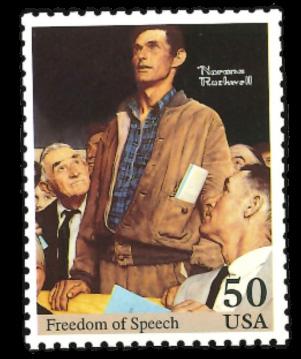

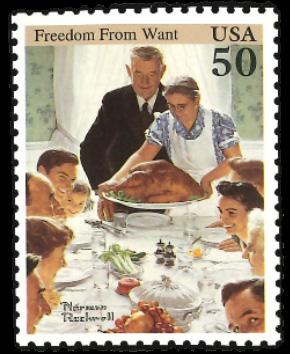

In 1941, when America was in the midst of World War II, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt spoke to the country in his State of the Union address. He laid out four freedoms—Freedom of Speech, Freedom of Worship, Freedom from Want, and Freedom from Fear—that he believed to be the right of every person. Two years later, iconic American artist Norman Rockwell created the Four Freedoms paintings, a depiction of the concepts laid out by FDR. Today, the vibrancy of these freedoms feels faded as extreme political and social polarization fractures our country. Faded Glory reexamines these freedoms in a modern context, sparking conversations about the nuanced challenges our country currently faces—and will face—in the coming years.

We are a fashion, culture, and art magazine. Art always has been, and always will be, a mirror of its times, historically serving as a powerful means for raising awareness and driving change. From Keith Haring’s 1980s art highlighting the AIDS epidemic to Picasso’s 1930s work protesting war, art has consistently served as a vessel for awareness and a call for change. With times as challenging as these, we see it as our responsibility as a collective of artists and creatives to use our platform with intention. Faded Glory is Strike Boston’s contribution to a narrative; it is a representation of our beliefs, concerns, and hopes.

Through this issue, we hope to highlight the complexity of the country. America is a melting pot, a collection of the beauty of so many cultures, it is a refuge for those escaping bad situations, a place in which its citizens have the power to elect those they feel represent them. We recognize these positive attributes and feel privileged to live in a nation that offers such freedoms. However, we can also recognize the contradictions and hypocrisies this country is built on, and the painful history behind the freedoms we enjoy today. Faded Glory is an attempt to celebrate all that we have, but also to call attention to all the hard work that must be done to turn these concepts of freedom into a true reality for all Americans. As James Baldwin famously wrote, “I love America more than any other country in the world, and exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.”

Issue 06 is a culmination of the hard work of our team of extremely talented and motivated creatives. A picture is worth a thousand words, and our visuals capture the nuanced emotions and complexities woven into the fabric of our nation. But as evocative as these images are, our words are worth a thousand pictures; the articles written by our writing team bring depth and perspective that complements the visuals they accompany. So as you flip though Faded Glory, we encourage you to read the articles that go along with each shoot, as each component works together to paint a full picture.

Faded Glory transcends a simple critique of a divided nation; it is an invitation to remember and to question, and a call for each of us to uphold democratic values. As we present our modern interpretation of FDR’s Four Freedoms, we invite you to consider these inalienable rights within the political landscape you inhabit. Reflect on your role in ensuring that these freedoms and their ideals are upheld and strengthened so they do not simply fade away. Our generation is the future, and we believe that our voices have a space in the conversation.

NAOMI COHEN

Publishing issue 06 marks the end of my third semester as editor-in-chief, yet writing this letter never seems to get easier—I have so much more to say than can fit in one page. Strike is the defining highlight of my college experience, and it has become so much more than a creative outlet. The hours I’ve poured into this magazine have shaped me—as a leader, as a collaborator, as a creative, and as a person—in ways I never could have imagined. Every moment has been amazing, and I feel incredibly lucky to be a part of this team.

Bella and I began developing the concept for Faded Glory last spring, knowing from the start that it would be a challenging theme to approach. We went back and forth countless times, figuring out how to execute it in a way that felt meaningful and sensitive. We knew the result of the 2024 election would impact our creative direction and we remained mindful of its influence as we worked. On November 5, after gathering our own individual thoughts, we quickly regrouped to refine the tone we wanted to set. Our team brought that vision to life, and I couldn’t be prouder of what we’ve created together.

Working alongside this team has been a true gift. I want to thank every single person on this team—your hard work, dedication, and creativity have not only brought this issue to life but made the entire process truly enjoyable. I owe a special thanks to my co-editor, Bella Bohnsack—my design soulmate and collaborator in every sense of the word. Bella, working with you has been so incredible, and I only wish we could do this forever. My deepest thanks also goes to my friends and family for their constant support. Mom, Dad, Jonah, Caleb—thank you for always being there.

Creating issue 06 has been a labor of love, and I am beyond excited to finally share it with all of you. Thank you for being a part of this journey. I’ll see you next semester ;)

Strike out,

BELLA BOHNSACK

What a semester, and what an issue! I joined Strike Boston as a freshman for our first issue (which feels like forever ago), so it feels surreal to be a senior finishing our sixth issue. As this was my last issue as an Editor in Chief, I can’t think of a better issue to go out on. Faded Glory has a very special place in my heart, as it was particularly challenging, given the complex and sensitive nature of the topics we explored. The amount of thought, care, love, and hard work that was poured into this issue by the Strike Boston team is something I am truly proud of. I am forever grateful to everyone at Strike Boston (especially my incredible Co-EIC Naomi) for making my time as an Editor in Chief such an unforgettable experience. It will forever hold a very precious place in my heart.

To say the 2024 presidential election was disappointing is an incredible understatement. It was heartbreaking. My heart, my love, and my prayers are with all women, people of color, members of the queer community, migrants, and all the other marginalized communities within the United States who will feel the impact of these next four years. If you disagree with my disappointment, sadness, and heartbreak, I don’t care- sorry not sorry.

I also want to use this space to give a couple of shoutouts. First of all, a massive shoutout to everyone in the Strike Boston issue 06 staff. You all killed it, and I am constantly blown away and inspired by your talent, work ethic, and thoughtfulness. Secondly, Naomi. It was a joy (as always) working with you. You are a star. I don’t know how I will work with anyone else in the future. You set the bar high, and I wish we could just keep doing this forever- it’s so much fun. You have no idea how excited I am to see where you take Strike Boston for issue 07. Finally, an extra big shoutout to my roommates and my family (especially my mom)- I would not be able to do any of this without your love and support.

I love you all.

EDITORS IN CHIEF NAOMI COHEN BELLA BOHNSACK

SOCIAL MEDIA MANAGER

Ella Strayer

SOCIAL MEDIA CONTENT

Director: Tracianna Walcott

Hannah Lashin

Madison LIoyd

Kayla Baltazar

Madeleine Dorman

Jewel Silva

SOCIAL MEDIA GRAPHICS

Samantha Sanders

Brian Curry

Sanju Menon

Vivian Wu

ADVERTISING

Director: Grace Pisciotta

Sofia Bernitt

Helena Wang

Ava Spurgeon

Hwarin Zoh

Lydia Velasquez

Christina Chen

FINANCE

Director: Tejirie Ogufere

Director: Dia Arora

PRODUCTIONS MANAGER

Sarah-Eve Gazitt

MULTIMEDIA

Director: Ashley Braren

PHOTO

Ellie Watson

Isabella Oland

Maria Dikman

Pablo Gonzalez

Lucas De Oliveira

VIDEO

Dylan Record

Tyler Hom

Rachel Solomon

EDITORIAL DESIGN

Director: Alicia Chiang

BEAUTY

Director: Maria Fischer

Ella Strayer

Sarah-Eve Gazitt

Mindy Tran

Sophia Groen

Rebecca Livstone

STYLE

Director: Sof Martinez

Shannah Virivong

Katie England

Capri Bold

Sophia Tierney

Chloe Rowen

WRITING

Director: Rachel Zhong

Rachel Yu

Esmeralda Moran

Alissa Doemling

Altea Peyser

13 U.S. STATES REPRESENTED

6 COUNTRIES ACROSS THE GLOBE

17 COUNTRIES REPRESENTED BY OUR FIRST-GEN STAFF’S PARENTS

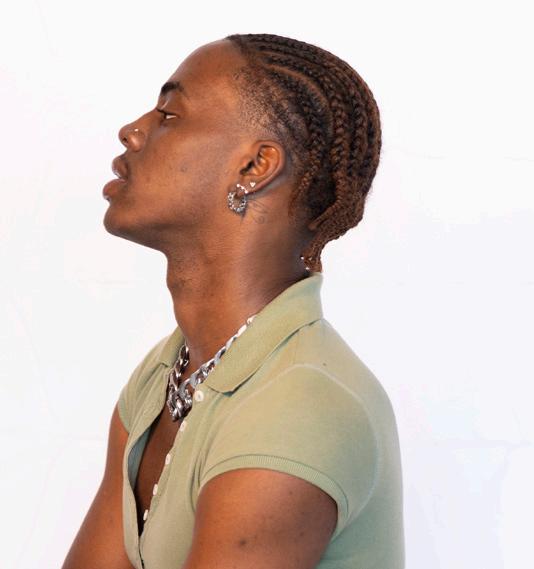

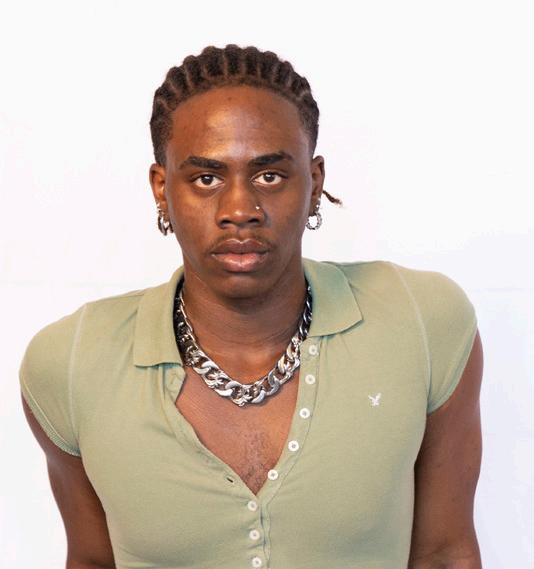

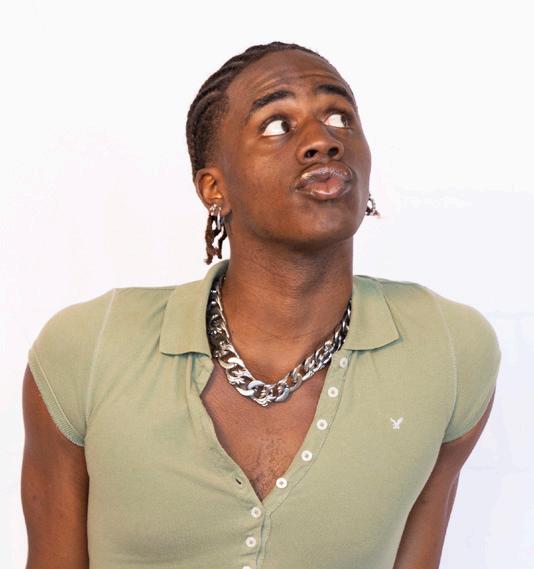

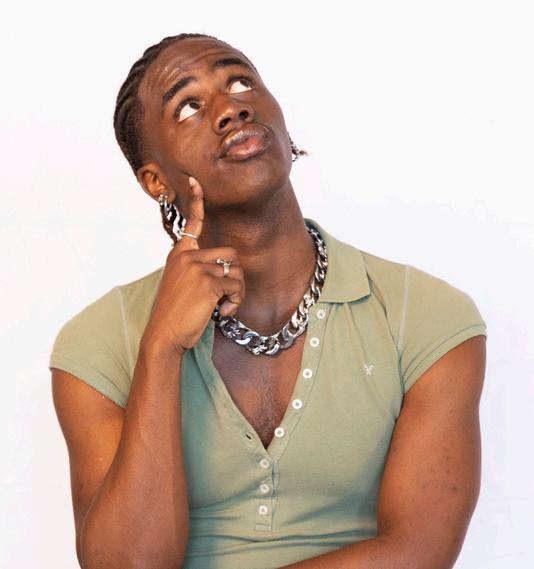

Shot on the nineteenth of October twenty twenty four at 42.350320, -71.111570 for issue 06 of Strike Magazine Boston’s “Faded Glory.” Editorial design completed by Alicia Chiang, Naomi Cohen, and Bella Bohnsack.

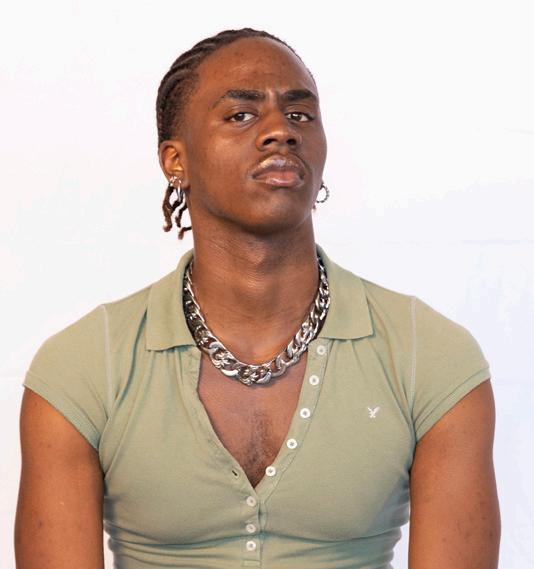

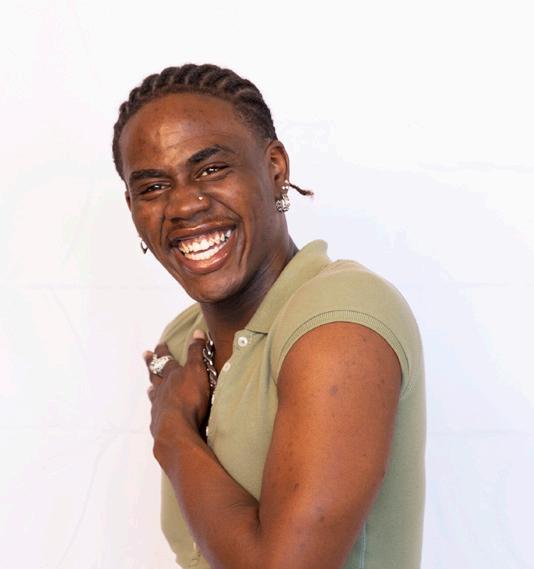

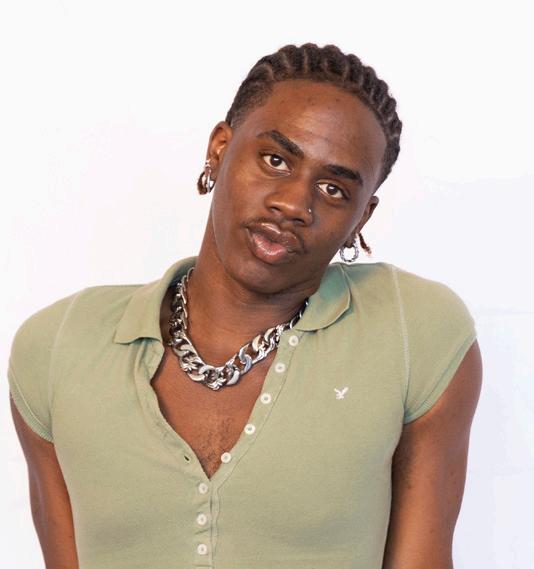

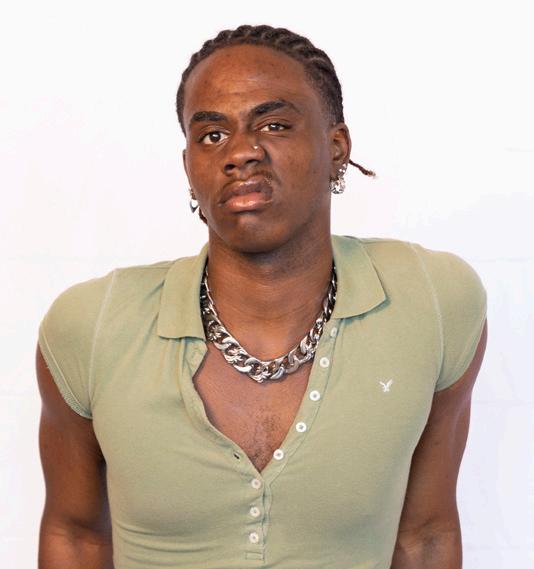

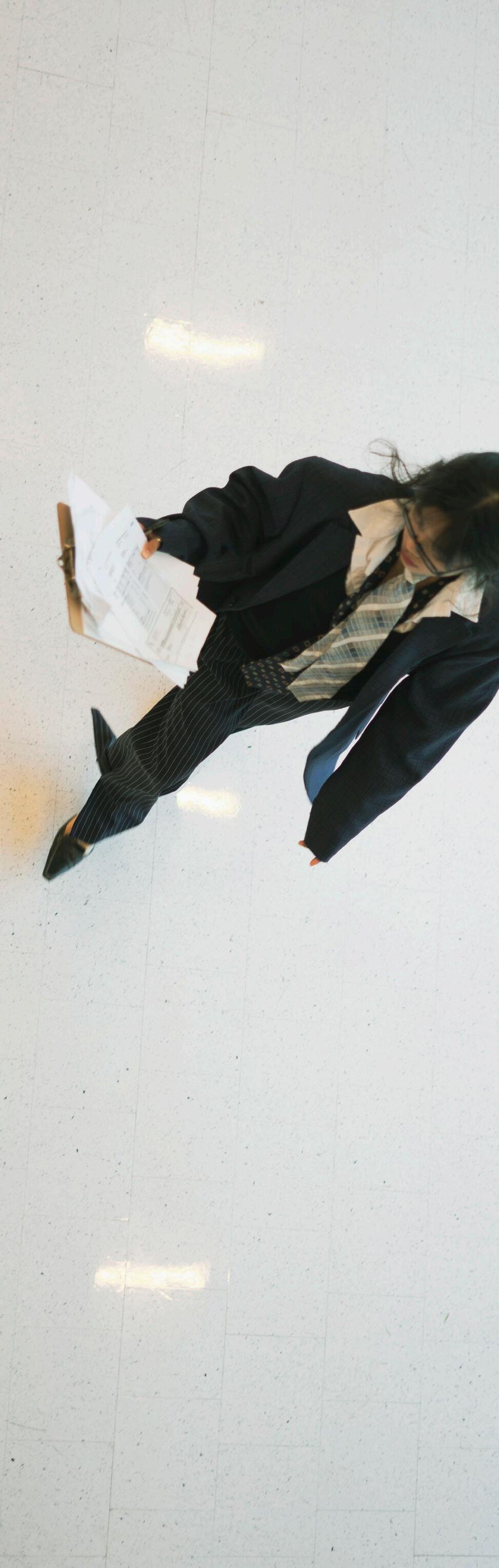

A lone blue-collar man with weathered hands and dirty clothes stands up in a town hall meeting, an outlier in a sea of neatly dressed attendees. His white-collar counterparts look upon him as he dissents—not with disgust and annoyance, but with attentiveness and curiosity. This is Norman Rockwell’s interpretation of Freedom of Speech— the first of FDR’s four freedoms.

A free and democratic country where every citizen has a voice. Americans can vote according to their beliefs and have the power to elect those who will make decisions in the country’s best interest. They can access independent news sources and freely share their opinions on current issues. However a closer look at America reveals that this freedom is not, and seldom has been, as rosy as it seems. Voter suppression, corruption, prejudice, and hate are as ingrained in American history as the ideals upon which it was founded. Despite collective action, protest, and persistent advocacy, Americans are often powerless in the face of the few who hold influence.

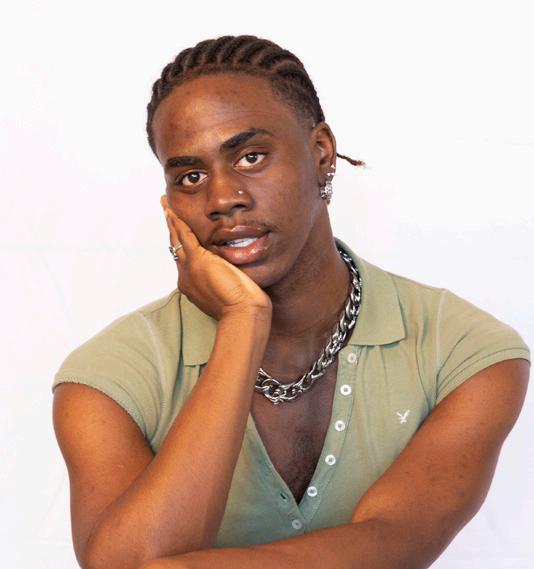

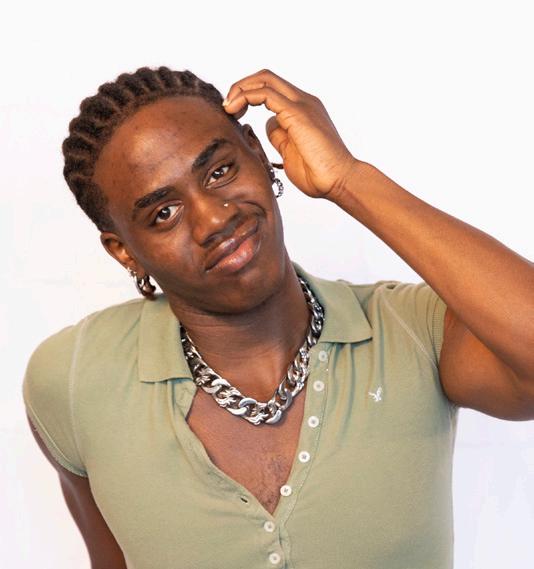

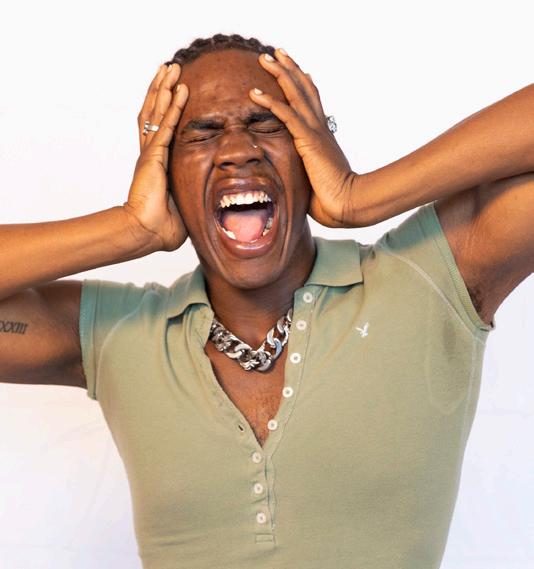

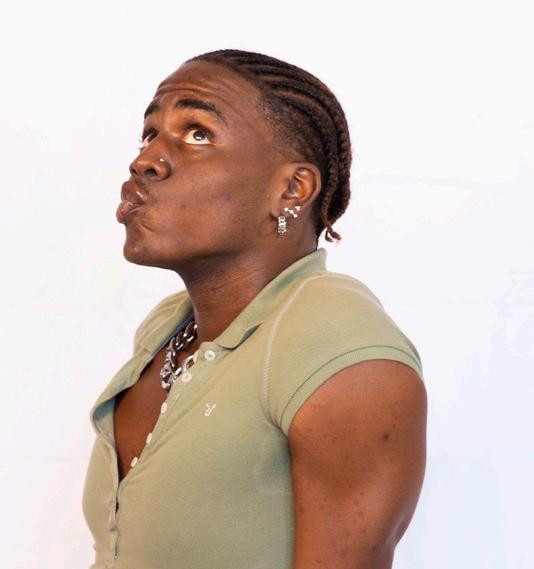

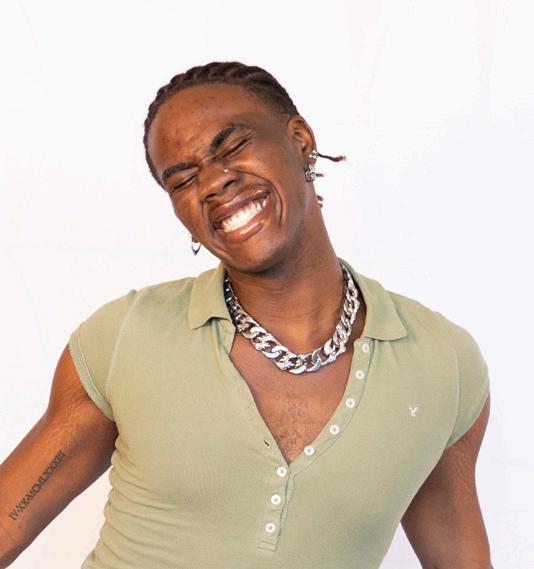

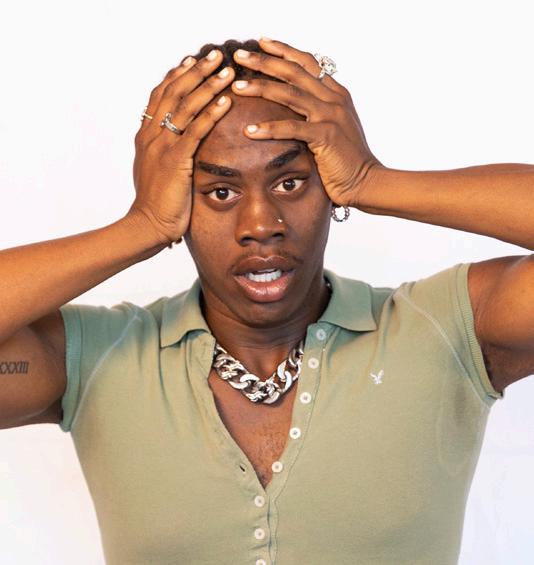

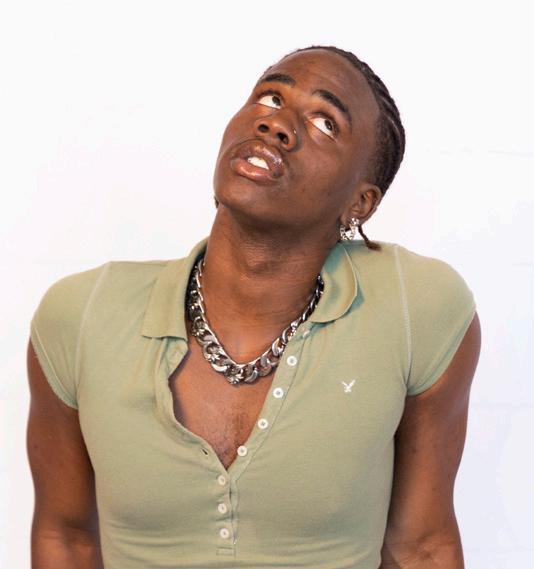

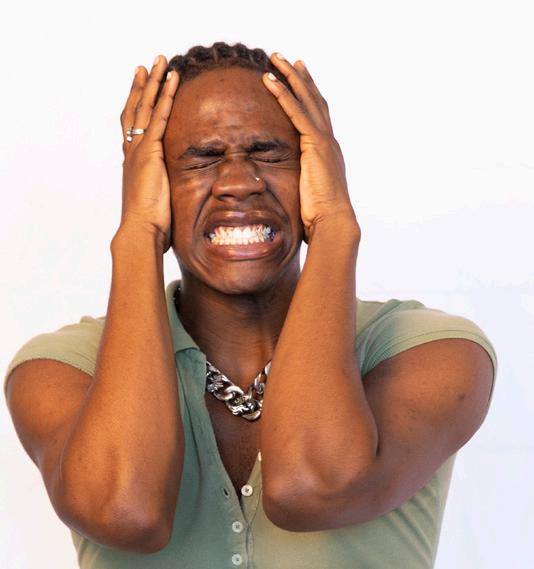

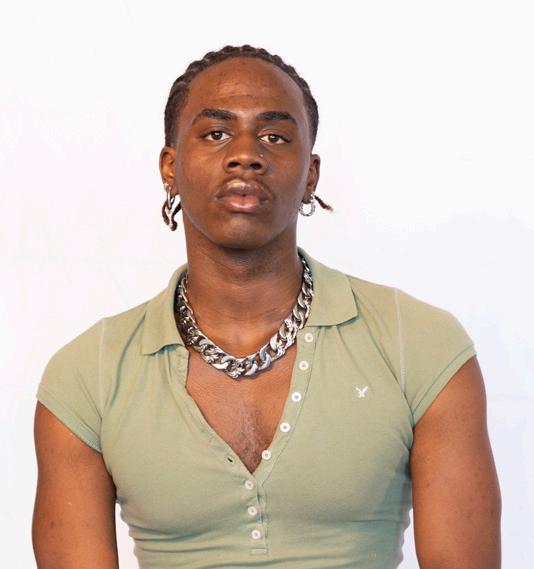

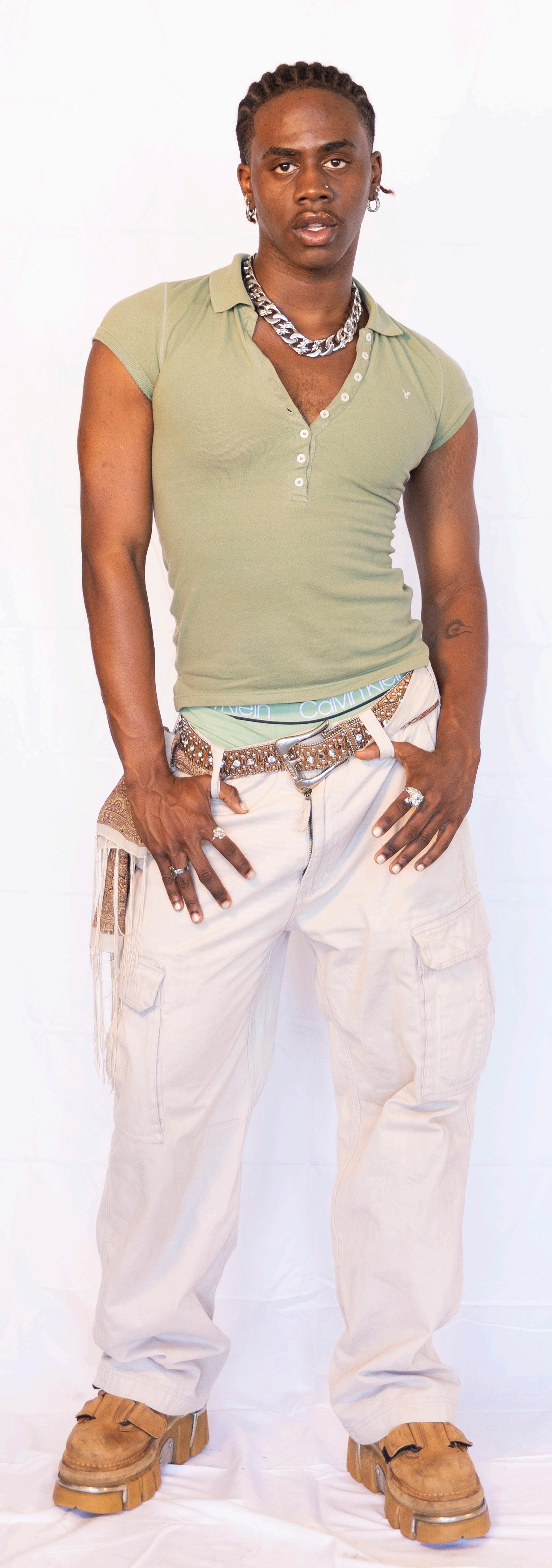

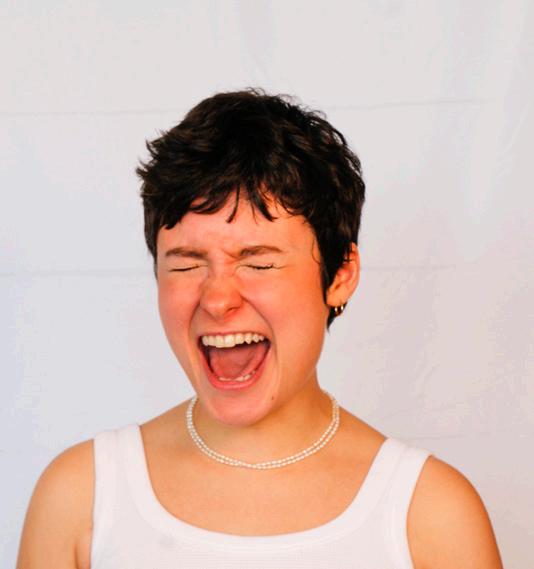

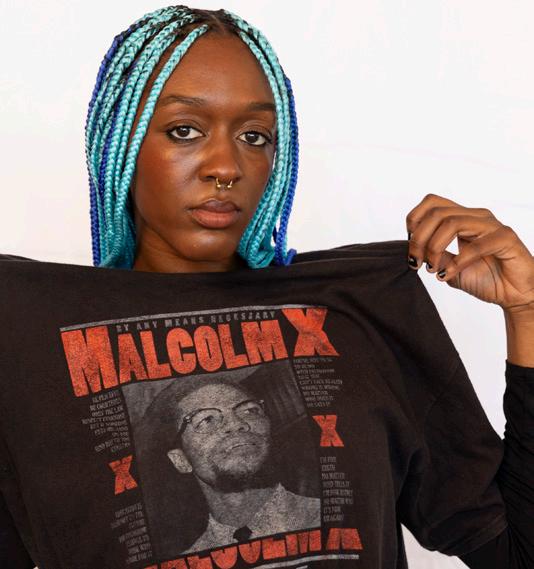

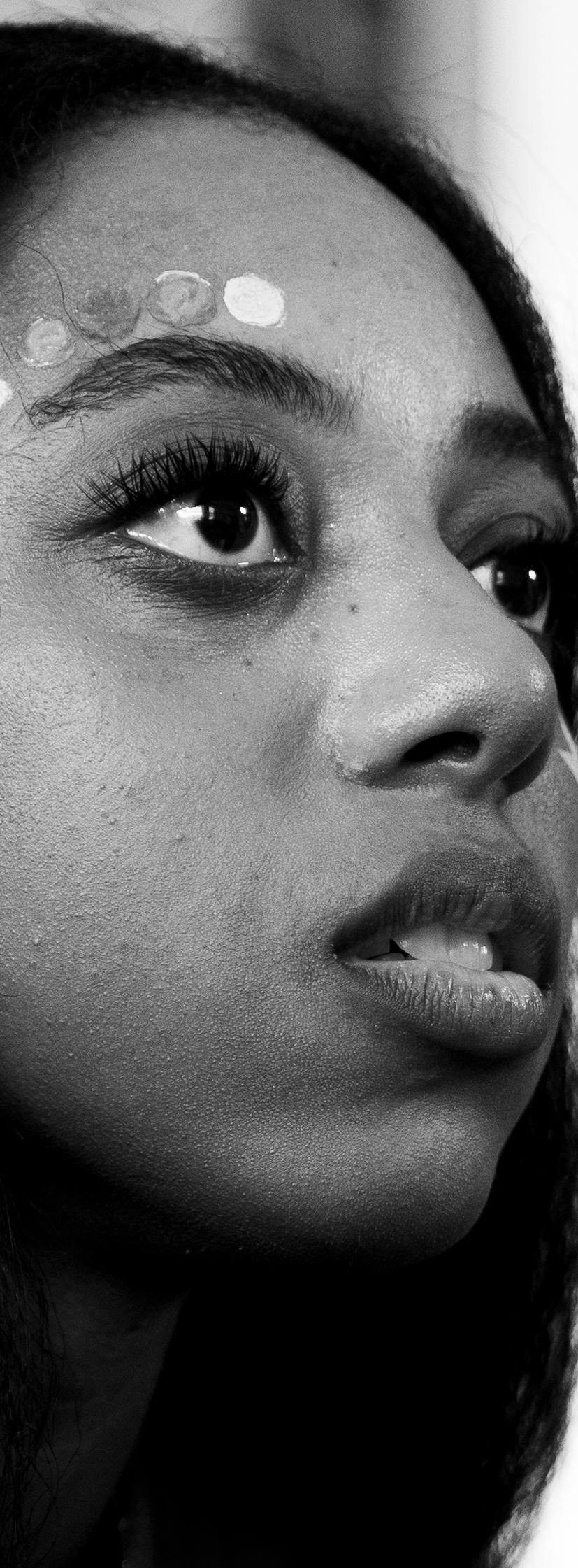

With an awareness of the limitations of freedom of speech as a tool for change, this shoot explores the concept on an individual basis—the freedom of expression. Featuring photographs of people in their most natural form paired with interviews, this shoot celebrates the individuality and unapologetic uniqueness of the next generation of leaders. It offers a glimpse into inner identity and how it is expressed outwardly through physical appearance.

SHE/HER TWENTY

PREMEDICAL NEUROSCIENCE MAJOR

INTERVIEWED BY ESMERALDA MORAN ON OCTOBER NINETHEETH TWENTY TWENTY FOUR

Why did you decide to stay in Boston for college? Did you think you would end up here? I wanted to go to New York. I was like, I’m queer, I’m young, I’m black, and I’m fun. Why would I be in Boston? Like, this place has always felt very restrictive. This place has always felt very restrictive for me. Like, I go study abroad. Every single semester I’ve been like, I go abroad, like I have fun. My mom encourages me, like, she loves the idea. She was also untraditional, like, she was a traditional Nigerian growing up, but like she was raised untraditionally Nigerian, so, like, she was never holding me back from anything.

Do you feel like you have to make your personality accessible?

Yeah, so like, this is me, and like this is how I talk when I’m in class, because, you know, we need to have your white people voice, but it’s just, I don’t know it’s, it’s definitely interesting when you kind of have to do that transition. I know going to college with white people is completely different, because there’s the idea of, like, class difference. Class didn’t hit me so much until I got to college, because especially at BU... when I grew up, it’s like we knew who the rich kids were. So it wasn’t until I got here, when I really started feeling the impacts of literally not being able to afford the same opportunities as people around me.

Is there anything you’ve picked up from your parents?

Yeah, like, I never grew up with the idea to not feel confident. And thankfully, my mom wasn’t, like, colorist, which is very predominant in, like, Nigerian communities sometimes, but she never was. She’s very light. But she grew up very Nigerian prideful…. I never had insecurities that were formed at home. They were formed at school, really. She’s also six feet tall. She wears four inch heels. I’ve never seen anything shorter. She’s a gala girl. She always grew up, like, every outfit was customized. Everything that we went to Nigerian events for, which were big gala events, were customized. She’d get fabric from home. She was very comfortable in herself. She walked around as such. She, like, growing up, she had to make herself seem like this bigger than life figure. And that’s how mothers really do feel like in households of color, I feel like, yeah. She made herself feel so, like, big, like she’s like, Oh, they try to cross me at work. I’m gonna show them who I really am. Like, that’s the type of person she was. I come from a household where my mother was such a dominant figure, and that really, like, translated down to me in the way I pursue things. I want to be overly grossly educated. I want to be super over accomplished. I love pursuing all activities of my life.

You’re first gen, yeah? Did you kind of find it difficult to navigate culturally?

That was a very big impact as to why I was a lot more quiet growing up. And I’m West African, but at the time, like, being West African wasn’t considered something I would be proud of. I have very West African features. I’m very, like, very purely Nigerian. Like, I’m a little Egyptian too, but, like, it’s not the culture that I grew up in. But, like, I could never really deny it. Not that I wanted to, but I never had the chance to. So it was like, there was this moment of ostracization growing up in a predominantly white institution. But just, like, I’m very comfortable with myself now compared to high school. But that was a very big transition, of having to adjust. Lowkey Black Panther was like when people started being okay with the idea of, like, Pan Africanism. And it’s not a westernized sense, and it’s a very, like, African origin sense. And so it wasn’t until then that, like, tribal pride started coming out. It wasn’t just like Nigerian, it was like my tribe.

In high school, did you ever get involved in clubs? Extracurriculars?

Yeah, I was a big club girl. It just really depended on how much time I had after class, and because my parents worked and things like that, I just would stay after and so I was part of like, 10 clubs that I would just circle through and go to. I was a part of, like, oh, a fashion design club, I was part of, like, an anime cartoon club, I was part of a drawing club. I did like, poetry, I really loved my poetry club. Writing club, pre health and medicine. So I kind of just, like, did everything that catered to all my interests. And then in terms of, like, sports, I did dance for like 10 years up until high school, and then I did track during high school. So but I wasn’t really, like, a track, track kid. Like, I didn’t have like, the knee brace or anything.

When you were in high school, what kind of kid were you? What did your report cards say?

Um, I was definitely, I wouldn’t say goody two shoes, but I was, like, compared to my other siblings, I was definitely the more academic rigorous type. Like, my mom growing up never went to my, like, conferences. Never was concerned about necessarily my position in class, in terms of, like, how I’m doing academically, because I’m okay with fending for myself I guess. But I was definitely, like, the black sheep, like, I was definitely like, very rebellious in the way where it’s like, I would challenge. I’m Nigerian, so it’s like, we have, like, you know, traditional norms. And I would definitely challenge that. But that’s definitely how I grew up. I was definitely really quiet, shy up until, like, high school.

INTERVIEWED BY ESMERALDA MORAN ON OCTOBER NINETHEETH TWENTY TWENTY FOUR

Can you tell me a little about yourself?

I am the oldest of four siblings, and holy shit. I feel like my identity is, like, always surrounded by everything else around me, as opposed to, like, me talking about myself. But I am a lover of everything creative, artistic, but also everything like science, logical, mathematical. So I try to balance both worlds in different ways, and they’re both huge passions of mine.

How did teachers used to describe you on report cards?

That’s a great question, because I was the kid that was always well put together. Straight A student, always listened to everyone’s directions, but I always talked out of turn, and I always said whatever I wanted. And that did cause a lot of problems, but it really helped me with my own expression of myself and, like, me growing up. But that was always on my report cards, like, she doesn’t shut up and she needs to focus on task, even though she’s a good student.

What is it like to be a woman of color in STEM? Yeah, for sure. I actually think this is a really, like, interesting answer, because people expect South Asian women to pursue this kind of field, and people kind of, like, expect us to be like doctors,

lawyers, engineers, and they like us to fit that stereotype. And in a way, I was trying to combat the stereotype of, I did it because I had to, and replace it with, I did it because I want to and I’m passionate about it. So I’m kind of trying to, like, I guess, pursue this career channel, and show my passion for it, as opposed to like, Oh, I did this because it’s in my culture, that sort of thing.

What is it like to work with so many men?

I think there is, like, beauty in feminine qualities, like traditionally feminine qualities of, like, diplomacy and, like, being sensitive. And I think I kind of try to balance the sensitive and diplomatic and empathic aspect of myself with, like, also advocating for myself. So at the same time, I try to hear people out, see where they’re coming from, but also, like, I don’t let people’s opinions of me dictate how I’m supposed to feel about something. So I kind of just let people talk and do their thing, and then people who want to change will allow themselves to be changed, and people who want to bring you down can only bring you down if you let them so.

What would you say to your younger self?

I would tell her to do exactly what she’s doing, because at the time, or even now, you think about whether what you’re doing is right or wrong, and

you’re always concerned about how it’s going to affect the future, or how it’s going to affect, like, who you’re going to become, but I think that who you are going to become is always going to be what it’s meant to be. So like, just keep doing what you’re doing.

Do you see your younger self in who you are today? Or have you evolved into something else?

I definitely see my past self now in myself, because I see her in, like, the way that she walks and bosses people around, is overconfident and talks a lot. And I also see the parts of her that have grown that, like, were very emotionally distant, that were, like, not so empathic, and how she’s kind of grown to be a little bit more than herself. So I see both.

Do you take any inspiration from your younger self? I definitely think I do, because I wore some of the most horrendous outfits ever, and I think just seeing what I’m wearing, I’m like, wow, she really did not give a fuck, like, I would wear my princess tutus and my rock star beaded necklaces and my tiaras out to freaking target, and I’d be like, this is what I want to wear today. And my parents, being the coolest parents they were, were like, that’s how she wants to express herself. Let her do that. And I think, like, seeing that expression and creativity not be inhibited or, like, downplayed, was so important in who I became, because it just let me be who I wanted to be.

Does culture have any influence on the way you dress?

I think for sure it has. Because being South Asian, being Indian, we love color, and we love, like, vibrance and going all out and just, like, looking like a bedazzled, like, piece of disco ball. Um, so I feel like that’s definitely influenced me, especially, like, with respect to jewelry, because in Indian culture, we kind of value more gold jewelry, and it’s more of, like, a thing for us, but Western, like, you see a lot of silver, you see a lot of silver going on. So, like, I mix those, and I just wear a lot of mixed metals.

Did you expect yourself to end up in Boston?

Actually, I never thought I would be here. I thought I was gonna live in Chicago forever. I thought I was gonna do, like, the cookie cutter route of, like, live with my parents and move out, and I’m staying close to home, that sort of thing. But I’m really glad that I did move out, and that I moved across the country because I was able to build a life for myself and, like, do my own thing, but also, like, explore what else the world has to offer, and that’s really cool.

If you could have a dinner with any five people, living or dead, who would you pick?

I’ll add six to that because I would have every single member of my family at one table. So I’d have my brother, my mom, my dad, my stepmom and my two sisters.

HE/HIM

ON OCTOBER NINETHEETH TWENTY TWENTY FOUR

Do you experience stage fright and how do you deal with it?

I feel like, with me, one of the reasons why I even got into theater was because of, like, how much, how exhilarating it felt. It felt being on stage, like, in front of people. I feel like stage fright, for me, is something that, like, I don’t know, I feel like I kind of enjoy, which is like, kind of crazy, like, I enjoy the like, anxious energy that it gives me, because it means that, like, I care, and like being able to, like, use that to like, entertain or educate or or like entertain or educate has just been like, so, so beautiful.

Okay, so on the like on Death Row, what would your last meal be?

Oh, it would probably be something home cooked and from like my mom, my aunts and uncles, like a really good soul food dish, like baked macaroni and cheese, baked beans, like some grilled chicken and like, it would just be Easter, Easter dinner.

If you won an Oscar, who would the first person you would go and tell?

The first person I would go and tell, I would tell my mom, like, in a heartbeat, she would be the first person that I would call just because I feel like she’s been with me on this journey for the longest, and

like, although it hasn’t been, like, easy pursuing this because, like, it’s just a very time consuming, like, ordeal. I feel especially like when you’re growing up, you’re still in school and trying to act but I feel like my mom has always pushed me and inspired me and told me that, like, I can do anything that I put my mind to, and all it takes is, like, working dedication.

Where do you stand in birth order?

I’m the eldest.

Okay, so do you give a lot of advice?

Yeah, I feel like I like, I have to be kind of like someone that is like they can rely on, or like they can go to when they’re like, in trouble, or like, need someone to, like, help them see something from a different perspective. I feel like, yeah, because me and my brothers are all very different. They’re all very, like, masculine, like football players. So it’s like, been an interesting like, balance growing up with like, being the oldest and still being someone that, like, they can trust or they seek, like protection from when, like, physically like they are, like, the like, stronger ones, you know what I mean? So it’s like, yeah, I love my brothers. I do. I miss them so much. Yeah, a little basketball team.

Would you be a parent?

Oh, yes. I think, I think when I learn to be a little like, less selfish of a human being. Because I feel like right now I’m very, like, young, spirited, and I very much have my priorities first, and that’s just not the mindset for no child. Um, but yeah, definitely in the future, I would say maybe not a lot. My mom had a bunch, and now, like, I have four brothers.

What advice would you give your younger self?

Girl, I’d tell my ten year old self, girl, calm down, please. Because I feel like I’ve always known that I wanted to, like, make a life off of being like an artist or creating, like, even since I was young. So like, I think the other side of that is being completely like, anxious and like, so focused on, like, getting there that like, you’re not, like, living in the moment, and you’re only ten, like, girl, you should not be anxious or stressed out. It’s understandable that you are but, like, chill and live life, because, like, there’s gonna be so much life coming at you in the next, like, few years, so just like, be there.

If you could be in any Broadway show, past or present, and have drinks with the cast after, what or who would it be?

Oh, it would definitely be the original cast of Dream Girls, the musical with like, Cheryl Lee, Ralph Loretta, Devine, Jennifer holiday that was, like, one of the first musicals I ever, like, really, really got into and like, lowkey inspired me to do theater just because, like, it was one of the first times that I feel like blackness on a stage was, like, associated with, like, elegance and poise. Not the first time, but my first time viewing like, viewing black people and this kind of, like, beautiful Hollywood landscape, and understanding that there, like, is a place, and we can make a spot for ourselves there. And like, this is just as much a part of our story, because it’s like, about exploring Motown and like, it’s like, about, our kind of supreme esque, like, girl group and like, just dealing with that type of, like, that section of black art, and like, I just love…I just love it. And the cast is stacked too, they’re all so amazing. And I would just love to be in that show.

How is Florida?

It’s, it’s like home to me. But like, I feel like Florida has so many different types of people within it, um, like, especially Orlando that, like, it’s like this, like, little petri dish. I feel like there’s like, the like, crazy, crazy, like Republican white people. But there’s also, like, a really big black population and a really big, like, Hispanic population. So there’s like, a lot of different people in Orlando, and I like it. I like…I like, it’s home for me.

What influences did you have growing up?

I grew up, like, my entire family is, like, black, like black and Southern, and, like, black American and Southern, um, so, like, my home life was very, very, like black oriented, like very African American. But like, when I would go to school because of, like, the schools that I went to, and like me wanting to pursue the arts and theater and stuff like that, it put me in, like, a lot of white spaces. So, like, it was, like, an interesting thing. Like, I would go home and be, like, very, very black, but then at school, it’s very, very white.

INTERVIEWED BY ALISSA DOEMLING ON OCTOBER NINETHEETH TWENTY TWENTY FOUR

Describe yourself in one word. Freshman year of high school, my English professor called me eccentric. I remember I took it as a compliment, I thought, this word definitely has a positive connotation. But then I looked it up and it kind of has a neutral leaning towards negative connotation…but I still like to think of it in a positive sense.

Describe your outward self in one word. Bubbly. I’ve had people meet me and get to know me a little more and say you’re completely different from how I perceived you first-impression wise. I come off very cheerful, very bubbly, very extroverted and I bring people out of their comfort zone. I try to volunteer to be the first one to open up the space for being vulnerable, but who I actually am, I’m very shy. I’m very reserved, I’m always ruminating and always in my own bubble, so it’s very much a concerted effort when I go and purposely interact with people.

Describe your inner self in one word. Sensitive. I feel everything so extremely deeply. It’s so hard, everything I experience is at such an extreme. The difference between feeling so completely energized and excited and euphoric versus the deep hole of depression that I sometimes spiral into.

What is one thing you wish more people knew about you?

My heritage because unfortunately people can’t tell and people are shocked that I speak Spanish, people are always shocked that I’m the first in my family from either side of the lineages; the entire before lineage was all from Venezuela. The entire before lineage was all from Cuba. People just see me and they don’t know me. So I just wish people knew that I’m half Venezuelan, half Cuban, and that I am the first of either side. And, like, it’s so crazy because, like, obviously then my uncles and my aunts immigrated to the states also, for so many reasons. And so then they had their children. So I have cousins that were also born in the States, but I am the first. So it feels like a big weight sometimes. Because obviously I did bio. They wanted me to be a doctor, and I’m not quite following that. So sometimes it feels like I’m letting them down because I was expected to, like, single handedly raise my family out of poverty and, like, raise us, like, a class system or whatever.

Who is someone that never fails to make you laugh?

My brother Andres. He is so funny, I don’t know if it’s because we’re only, like, 14 months apart. And so it’s so funny because when people grow up, like, so close in age like that, it’s almost like you

develop, like, a twin telepathy almost.

What does “being yourself” mean to you?

Accept the cringe. I always beat myself up about what social faux pas I just made. Like oh, I accidentally interrupted that person. Obviously, I am mindful of that, and I try not to do that. Or, oh, I just did a little TMI or, I was just way too reserved and it made everyone else feel awkward because I wasn’t extroverted enough. Sometimes you come into a room with anxious energy and it spreads, but I feel like I’ve been trying to forgive myself for it. Just trying to show myself, like, kindness and gentleness and forgiveness. And no one else is gonna remember, like, that word that you misspoke because you got, like, like, tongue tied. Like, you are the hardest person on yourself.

When was the last time you cried?

During therapy on Thursday. But also the time before that was the Sarah Kinsley concert. Her song Black Horse, there’s this one line to be wild to be obscene, to stop playing the first born daughter in the american dream. The way that hits, it just resonates so much. It was such a release to be able to cry during that, trying to release myself of those expectations.

What’s something you’re proud of?

I just feel like the world is so messed up and hard, there’s so much going on right now. I feel like all of us grew up with the fears of wars happening abroad that are a result of the U.S. We have the fears of, like, the recession while we were growing up, we have climate change on our minds, Like, it’s just I am proud of being alive. Like, it is a miracle that I’m still here, I feel. I’m really proud of, like, getting that BU degree. That shit’s hard. Like, I didn’t think I was gonna make it out of that.

How has the way you express yourself changed as youve grown and matured?

I’ve become more in tune with how I want to represent myself, and I’ve grown to become more comfortable with my femininity, and I think I’ve also become more keenly aware of how others perceive me in reaction to how I dress. So it’s a lot of self awareness and an awareness of how other people see me that has changed how I dress. It’s so nice to be an adult now because I get to actually choose what I wear every day. Sometimes it’s a flop, but other times, we slay.

What would you choose as your death row meal?

My mom’s carne molida. She also likes to put raisins in it, which is really funny. It’s a ground meat meal with potatoes, carrots, and all of her seasonings, and raisins and rice, and it’s just so delicious. That would be my last meal. It would have to be made by my mom.

INTERVIEWED BY RACHEL YU ON OCTOBER NINETHEETH TWENTY TWENTY FOUR

If you could describe yourself in one word, what would it be?

One word...I would probably say determined.

Describe your outward self in one word.

I feel like outward, like, I’ve heard a lot of people say I’m kind of, like, scary. I’ve done, like, crazy colors in my hair and I’m always, like, I just forget I even have them until someone points them out.

What’s something you’re proud of?

I’m very proud of the fact that I’m taking a lot of, like, I guess hard classes. Yeah, and I’m doing well in it. Like, I learned how to code. It’s actually really fun. I took my exam last week and it was, like, it’s easy, and I was like, oh my god, this is great! So I’m really proud that I kind of stuck with it. I taught myself a new skill.

Let’s say you just won a Nobel Prize. What would it be for?

I think I’d win for, like…it’d be cool if I got the peace prize. I think that’d be cool. Because that’s, like, oh, you’re going out of your way to, like, kind of like, get relations with other countries. Yeah, a hundred percent. Like, I’m not in international relations, but I think that’d be really cool if I could, like, yeah, go internationally and try and help people out. Yeah,

meet new people. With my law degree. Yeah, a hundred percent. I think it aligns with law as well.

Who is the first person you would tell?

Um, the first person I would call is probably, honestly, probably my best friend. Yeah. I was gonna say my mom, but like, my mom would already know. But I’d call my best friend. I’d be like, oh my god, like, we’re out here. Like, can you believe I won? Like, I’m probably crying. Her name’s Heaven. Um, but yeah, we’ve been friends since, like, what, like seventh grade.

When do you feel the most yourself?

The most myself? This kind of sounds like probably, oh, I keep talking about her. This is so embarrassing. But probably when I’m with my best friend. Or, like, when I’m by myself in my room, and I, like, I have nothing to do. Like when I generally have nothing to do, when I can, like, choose, and, like, put my time and energy into things I like. Like, I play guitar, um, or I’ll, like, play Sims, something like that. I’m just, like, by myself. I’m doing my thing. You know what I mean?

What’s your favroite song at the moment? Probably Be Sweet by Japanese Breakfast.

Who inspires you?

I have a few. I feel like my mom is, like, main thing. She’s an immigrant. You know, I mean, like, I’m not very, like, I guess, like, Christian. Some people are very much into it. I’m trying to get more into it, but, like, I’m not. Yeah, it’s like, that’s her thing. She’s never once, like, doubted it. She doesn’t doubt herself. She doesn’t doubt, like, what she believes. I guess, like, personal things I never doubt, like who I am or I’m not, like, what I can do. Things like that.

Dogs or cats?

Cats. Okay, let me I’ll explain. Cause, like, when I have my off days, I’m not getting up and going on a walk. Yeah, and you need to go feed the dog. Like for a cat, they eat whatever, they come cuddle with you. Like yeah, they’re like, very feminine. They’re very, like, always wanting to nap. Yeah. Dogs are very much men, they like to be happy…like always.

What would you choose as your death row meal?

Yeah, no, no. I could never go to prison, I’m serious. So first, for breakfast, first of all, my mom would be there. I don’t know why she’s there, but she’d be cooking my food. And she’d make me ackee and sawfish. It’s this Jamaican national dish, it’s really good. I get it for breakfast. And then for lunch, I would order all you can eat, like, sushi, like, seafood boil. And then for dinner, I’d get pasta and steak. And then for dessert, I can’t even eat all this, but I’m just gonna keep eating so they can’t kill me, you know what I mean? Just keep eating. And for dessert, I would get a nice vanilla, chocolate, you know the milk cakes where it’s a big circle? There’s chocolate inside? Yeah, I want that. I feel like I would need, like, Pepto after all of that. No, I’m gonna just keep going, keep going. And I’d be like, if it comes down to it, I’d be like, guys, just give me a shot, I’ll be okay. I need to die happy and full.

What’s one thing you wish people knew about you?

Probably that I’m very compassionate. I feel like I’m very empathetic and, like, I know it’s crazy to say cause people shouldn’t call themselves empathetic, but, like, I think in my experience, a lot of people wouldn’t expect that from me. I think I care a lot about people. I try to make their lives easier. Cause I feel like that’s, you know, like, treat people how you want to be treated or whatever. But also it’s like, I think by me doing that, I’m like, putting good karma out. Do you know what I mean? And I don’t really want it back. It’s more about like, I’m doing good things. So, like, over time, everything else would be better, if that makes sense. And I think it’d be great if people knew that. Cause then they’ll kind of, like, lean on me for support more. I feel like a lot of my friends, when we first started being friends, didn’t think I would be like that type of person, like, emotionally, like hugging, and things like that. And, like, over time, like, oh my God, like you’re so, like, you’re so silly and you love to, like, give them, you love crying and all these things. I’m a cancer.

When I walk down the campus of Boston University, I experience the street bustling with creativity and diversity of outfits. While I recognize some familiar faces, most are strangers whose unique stories are left untold in the second I brush past them. But through a quick exchange of looks, each stranger passing by could grant me a glimpse into their being, their personhood and their beliefs — all through the way they dress.

Reciprocally, I dress for the same intricacy and exchange of perception. I walk down Comm Ave wearing a cut-offthe-shoulder shirt that I altered, along with thrifted lightwash jeans paired with a brown leather belt. My outfit is tied together with my Japanese Onitsuka Tiger sneakers and an embroidered red jacket, which is a hand-me-down from my sister. Each of these pieces I wear tells a story about where I’ve been and what I believe in: the pieces I thrift represent an effort to maintain environmental and economic sustainability; the clothes I alter symbolize my own personal and artistic taste; the shoes carry a subtle nod to the Japanese culture I grew up in; and the handme-downs remind me of my family.

When I was younger, self-expression was often limited to my parents’ authority. The way I dressed was a proxy for my parent’s beliefs and perceptions, as they were the ones who picked out my outfits and bought my clothes. Most people have the true authority to explore their style only when they’re more grown and independent — for me, that was college.

Starting my college journey over two years ago, I fully realized the societal importance of fashion as a channel for self-expression. Every person has their own special and unique story, and the easiest way to tell that story is through our external means of expression. Fashion is a vehicle for us to express our beliefs, no matter how deep

or trivial, and it naturally evolves over time in conjunction with our beliefs. Growing up in the Bay Area and still figuring myself out as a teen, my fashion was based more on practicality than anything else. Now in college, I’ve gained a stronger sense of who I am and have truly begun dressing in ways that align with how I feel — my style has become a distinct part of me. Whereas before my fashion was much more feminine as I conformed to societal norms, I now feel much more comfortable straying away from these stereotypes and dressing outside of a gendered context. We are inherited with the ability to make a silent statement — whether based on faith, politics, or values — through the clothes we wear.

But fashion has also become increasingly complicated and nuanced, and is often inaccessible to many. With pressure built by social media and consumerism, everyday fashion has quickly become commodified into trends that come and go, leaving little room for personal creativity and expression. While fashion used to be an outlet for artistry and personality, with pieces so bold they were timeless, trends are now quick and impractical, yet inescapable. These eras of change have twisted the original intention of fashion as a true cultural art form.

In this generation, the fashion industry has become a double-edged sword: the need to look stylish has come at the cost of originality and makes it difficult to truly use fashion as a means of expression. Despite this evolving culture, however, fashion still holds the power to connect and learn from others. To combat the changing climate of fashion, we can still reclaim our originality and creativity in meaningful ways. Whether that’s through the colors and brands we choose to wear, how we customize certain pieces, or how bold we make our statements, fashion offers infinite space for us to tell our stories however subtly or loudly we choose.

My first language was Korean. In my household, my parents solely spoke to me in Korean, allowing me to adapt to the language as I grew up. They stressed a sense of pressure to ensure I grew up speaking and deciphering Korean fluently. Whether it was over casual discourse at the dinner table, or through the K-Dramas on TV, Korean was the sole language exchanged in my house.

Despite our shared understanding of Korean, a language barrier remained between my parents and I — they didn’t speak English as well as I did. Both of my parents knew how to read, speak and write in English: my (father) got his PhD here in the States, and my (mother) took numerous English classes. Although my parents both studied the language comprehensively, there was still a slight obstacle, a wall between us. As my English gradually strengthened in school, my comprehension of it reached a sense of unfamiliarity for them. Yet my increasing proficiency in English slowly pulled me away from the fluency I once had in Korean.

Although my family spoke Korean only in the house, whenever we’d go out for dinner, run errands or attend appointments, I obligatorily played the role of a “messenger” for my . When ordering her food or scheduling appointments, I would speak on her behalf. This eventually became habitual—my would rely on my English knowledge to relay her thoughts.

My knows enough English to speak for herself and is confident in her ability to do so, but the option of having me as her “translator” provides her with a sense of comfort and reassurance that her thoughts are being expressed verbatim.

But the roles are ultimately reversed once I’m placed in a Korean-speaking situation with my or : they speak on my behalf. I know enough Korean to speak fluently, but having my parents speak for me feels convenient and, frankly, easier.

As I relied on my parents for communication, I began to allow others to speak for me. My tendency to align with what other people thought intensified, even at times when I felt otherwise. Because growing up I was taught to avoid being an inconvenience to others, I became comfortable with the idea of “people pleasing.” I considered the opinions of others before my own.

In situations when I was asked to express my opinion, I would always go for the safer option—lying when asked if I was hungry, or saying I liked things I didn’t. I knew I had a voice of my own, but I would allow external voices to drown out my own.

It was an easier route. I didn’t want anyone to feel like I was burdening them, so I kept quiet in many situations to avoid being an inconvenience.

As I observed positive reactions to my submission, this obedience became a standard practice. I felt like more people enjoyed my company if I simply agreed and

complied. I would avoid sharing how I truly felt out of fear of feeling like a hindrance.

I always believed this behavior was a product of empathy, and I convinced myself this was the only way I could make others like me. I allowed external opinions to dictate my own. I convinced myself that my “people pleasing” was acceptable, as long as I was maintaining an agreeable and down-to-earth reputation amongst others. Though I didn’t want to allow others’ opinions to pulverize mine, I felt as though it was the easier option.

Despite the power my voice held to translate for my , I couldn’t figure out how to speak for myself. I had a voice to relay messages for my , but I didn’t have a voice of my own.

Now, as a college sophomore, I am learning how to adapt to situations independently, and I’m gradually realizing that I’ve never truly prioritized my own feelings and opinions. Although I still struggle with communicating my thoughts and avoiding people-pleasing tendencies, I’m starting to acknowledge how voicing the most authentic version of myself allows me to gain a stronger sense of comfort and reassurance than I had before.

By attending university in a more fast-paced and dynamic city, I’ve begun to realize that no one will listen to your opinions unless you voice them succinctly. I ultimately learned that you need to share a healthy, reciprocating relationship with your thoughts.

I remain attentive to the opinions that people have regarding me and my personality. I’m someone who cares deeply, maybe too deeply, about how I’m portrayed from an outside perspective. But there comes a point when one has to realize they don’t have control over the perceptions that people will hold of them.

When I was growing up, the language that was being spoken at any given moment determined the voice that was given a space.. Now that I’m nearly 20 and living away from home, I’ve finlly become accustomed to speaking confidently on my own behalf. Overall I feel as though I’ve given myself a new mindset. Ever since I have committed to prioritizing authenticity, I have constructed so many fulfilling relationships and connections. We tend to overlook the power our voices have—but becoming your authentic self comes only when you develop confidence and comfort with your own voice.

PAGE LAYOUT: ALICIA CHIANG, NAOMI

INTERVIEWERS: ESMERALDA

Shot on the second of November twenty twenty four at 42.345670, -71.118670 for issue 06 of Strike Magazine Boston’s “Faded Glory.” Editorial design completed by Alicia Chiang, Naomi Cohen, and Bella Bohnsack.

Norman Rockwell’s iconic painting, “Freedom of Worship,” depicts a diverse group of individuals united in their respective faiths. While Rockwell focused on traditional religious practices, this shoot explores a different kind of devotion: the fervent fandom of sports.

In the United States, sports have evolved into a cultural phenomenon, shaping identities, communities, and even national narratives. Like a religion, sports offer a sense of belonging, a shared purpose, and a set of rituals. Fans dedicate their time, money, and emotional energy to their teams, riding a wave of intense feelings—from the euphoria of victory to the despair of defeat.

This shoot delves into the emotional rollercoaster of sports fandom, capturing the passion, camaraderie, and collective experience that binds fans together. It explores the rituals, practices, and superstitions that accompany sports, highlighting the ways in which they mirror religious practices. By examining the cultural impact of sports, this shoot aims to reveal the profound ways in which they shape our lives and identities.

Rachel Zhong

If you haven’t noticed, Sunday service has taken on a new form, where Americans lock eyes on a screen split into four of the same ball-throwing, body-tackling action— better known as Sunday football.

Other than their name, these two Sunday activities function almost identically. Their crowd-gathering nature draws people for collective experiences, be it in a church or a stadium. Christians sing hymns, and sports fans chant. Beliefs, identities, and values are expressed and made tangible through these voices. Just as practicing religion can be likened to the daily ritual of eating a meal, being a sports fan is like partaking in that ritual, only with different dishes made from the same ingredients.

As the saying goes in the world of economics, “sports are like a religion.” Early on, however, when these two cultures were first compared, the “like” was omitted— sports were religious. As evident as the rivalry between Glasgow’sRanger Football Club and Celtic Football Club— one representing Protestants and the other Catholics—the pitch became a space that deepened their shared identity. This identity extended beyond the coach and players to include everyone involved, even the stadium janitors. Under the growing lure of capitalism, this case, from Franklin Foer’s book “How Soccer Explains the World,” eventually transformed into an inclusive, commercial brand – doesn’t it sound like today’s American franchise?

Major leagues take a share in capitalism and have reoriented the connotation of games and teams in our heads.

My observation of the Bostonian’s game day routine is as

listed: bar, beer, bets, booing, boasting in Boston team merchandise, more booing if lost and extended bender if won. All of these activities escalate when the opponent is their rival. My high school friend from Massachusetts made known that she would burn my Yankee hat (a Chinese fashion I once blindly followed). The sensation is even greater when shared with family and friends. Everything sports come foster with a greater sense of belonging formed among various identities as the fruit of globalization. From this point, sports uphold a benchmark distinct from that of religion.

“Soccer isn’t the same as Bach or Buddhism. But it is often more deeply felt than religion, and just as much a part of the community’s fabric, a repository of traditions,” writes Foer in the prologue of his book How Soccer Explains the World.

This ideology can be said for any sport but is most accurate to Americans. Pitches, fields, courts and stadiums blatantly roar to us the core of American values – achieving from hard work. In other words, sports are the never-ending chase of the American dream, where we worship the rousing success of our sweat and tears.

If, as Henryk Machón said, religion is attempting “a holistic interpretation of reality,” sports are attempting a holistic exploration of human ambition within that reality. To fulfill this shared social perception, sports take on a ritualistic nature in America. So, we participate in sporting rituals to stake our claim in the dream and engage in the most primal form of endeavor through physicality. Sunday Football somehow manages to hold our full attention in this digital age.

Esmeralda Moran

My Sundays were spent next to my grandfather, our eyes transfixed on the screen as we watched shortstop Derek Jeter make his way to home plate to bat and position himself to swing. We’re hesitant to touch our food, scared that the second we take our eyes off the screen we’ll miss the action. Sports commentator Michael Kay’s voice was steady, soothing us both as we took the chance and bit into our food. We watched as Jeter wound up his bat, swung, connected with the ball and ran like his life depended on it. My grandfather cheers, fork falling to the ground as he begins clapping, the noise echoing in the living room. There was no fear by the time Jeter reached third base; we knew he had it in the bag. It was when we saw him slide onto home base that we knew we were safe. Another point for the Yankees, another win as always. These were weekends well spent—moments like this are ingrained in my mind as my first experiences with baseball.

There has never been a time in my life when baseball didn’t affect my daily routine. Growing up just five minutes away from Yankee Stadium, my blood inescapably ran navy blue and white. The roar of the crowds drifted through my windows and hinting at whether or not they won that night. The YES logo was burned into the screen of my grandfather’s television and the remote at home had a shortcut to the same channel. I could never imagine a time without the sport playing somewhere in the background of my life.

Despite my lifelong allegiance to pinstripes, I realized I’d be entering enemy territory by going to college in Boston. Of course, I was aware of this rivalry, admittedly unbothered by the team and their fans who I considered too intense for my liking. The animosity of those fans was unfamiliar to me until I set foot in a stadium I was never meant to be in to begin with. Not only did I feel like I was an imposter, but a part of me felt like I was betraying my home team. The roar of fans in the stadium felt strange: it was smaller, but feistier as well. Despite the waves of red surrounding me, I made my home in the green stadium, still enamored with the spirit of baseball in my rival’s hometown. The crack of the ball against the bat is entrancing, the adrenaline fueled by the crowd’s cheers transfixes me, and I’m reminded every time of how much I love the game.

Although it may not rival football in popularity, baseball still embodies patriotism in the United States. The sport became a safe haven for patriotism as it rose in popularity during times when the country was under duress. The birth and growth of lionized baseball talents were a part of that ideology. Babe Ruth,a cornerstone of baseball history, rose to stardom in the midst of World War I. During these times, sports brought the American people together, offering a

sense of community and unity. As the country grew and opened its doors to other cultures and communities, the influence and popularity of baseball rose alongside it. About 10% of its members are Dominican, most coming directly from the island. Despite not being American, the influence of baseball is driven into our hearts and minds. Baseball culture is as essential to American culture as breathing is to living. The one driving force that unites our nation is sports, cultivating the best of us to form a community fueled by competition. It is in baseball that I find myself at home, knowing that for those nine innings, I am one with everyone around me.

The years spent translating for my family and navigating spaces filled with people from generations of established roots here – all of it fades away the second I step foot into a stadium. The wash of red or navy blue calms my nerves. Here, I could forget that English is not my first language and that I am the child of two immigrants who left their lives behind for better opportunities. It is here that I remember I am an important asset of baseball, and that my team thrives with people like me in it. It is in these stadiums that I am proud not only to be Dominican, but also American.

It is difficult to educate yourself about a new culture that’s seemingly exclusive. It is especially difficult when you don’t have the resources to help you fit in. Being a part of the first generation in my family to be born and raised in the United States, I found myself at a crossroads in navigating my identity. Was I supposed to push aside my origin and conform to Americanism just because I was born here? Or was there a way to coexist with the Dominican identity that had been passed down to me by generations? These questions burned deep into my brain and drove me into a bit of an identity crisis, so I learned to adapt to the people around me and take from them what I could, as it was the only resemblance to American culture I had.

But baseball made me realize that I didn’t need to adapt to sports culture. In America, sports culture breeds competition, with an ever-present need to outperform others – to be the best of the best. I was no stranger to this, spending my childhood in parks with baseball mitts and rubber baseballs. This sensation transcended the need for the same language, same background, same anything. When you stand alongside hundreds of other people, all cheering for the same sport, it’s hard to remember that there was ever a point where you were different from the person standing next to you. At that moment, you are all baseball fans and you are all Americans. Despite grappling with the ever-changing cultural landscape of the U.S., one thing has remained the same: the love for sports.

PHOTO:

PABLO GONZALEZ

LUCAS DE OLIVEIRA

VIDEO:

TYLER HOM

BEAUTY:

ELLA STRAYER

REBECCA LIVSTONE

SOPHIA GROEN

MARIA FISCHER

STYLE:

SOF MARTINEZ

SOPHIA TUERNEY

SHANNAH VIRIVONG

MODELS:

TRACIANNA WALCOTT

KALIKA REECE

RACHEL SOLOMON

KAITLIN AMADO

SOCIAL MEDIA:

TRACIANNA WALCOTT

MADELEINE DORMAN

PAGE LAYOUT:

ALICIA CHIANG

NAOMI COHEN

BELLA BOHNSACK

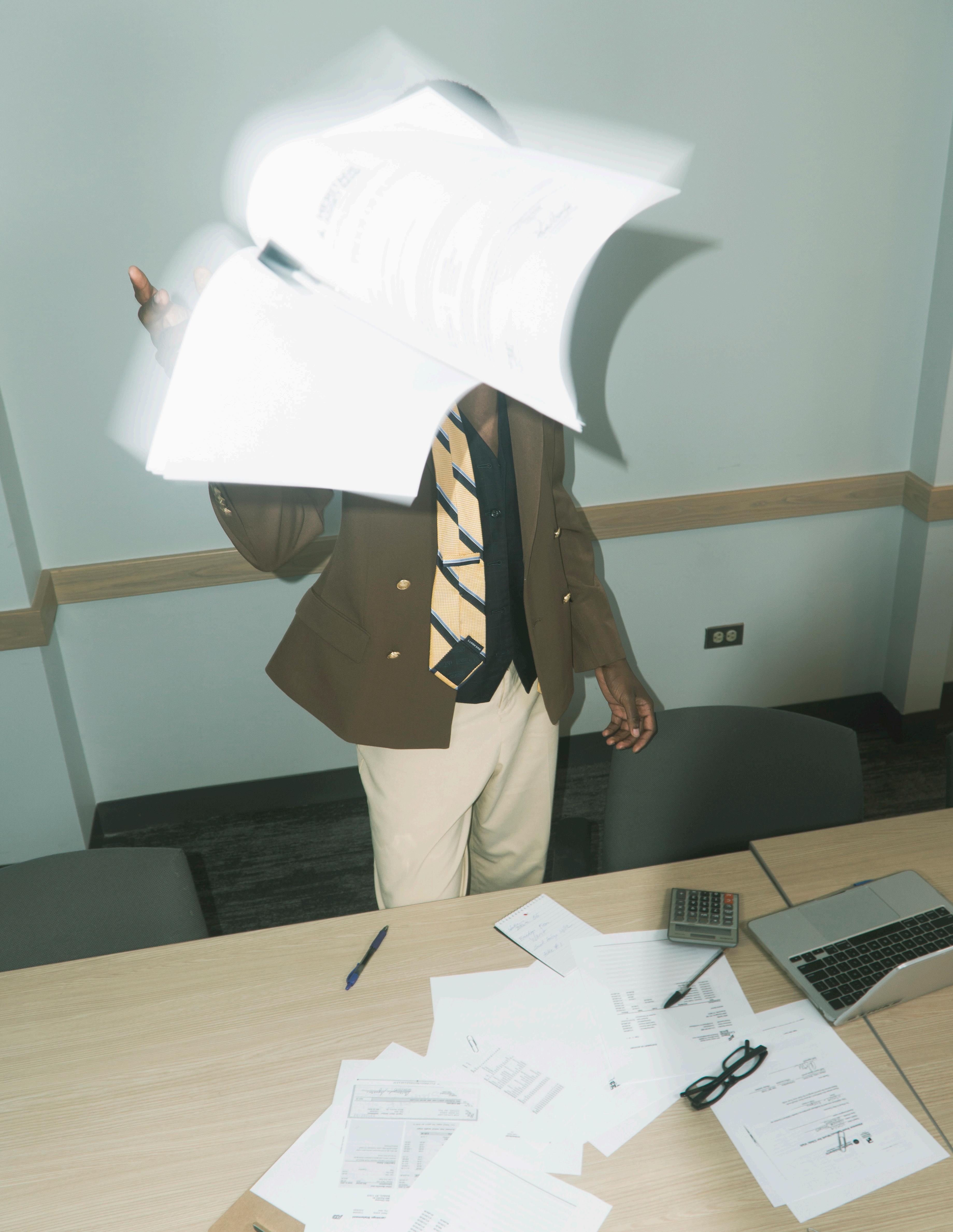

Shot on the twelfth of October twenty twenty four at 42.350761, -71.109039 for issue 06 of Strike Magazine Boston’s “Faded Glory.” Editorial design completed by Alicia Chiang, Naomi Cohen, and Bella Bohnsack.

Three generations of a happy American family gathered around the dinner table. Despite the bountiful meal before them, the diners do not look hungrily or expectantly at the food, but instead look lovingly and happily at each other. This is Norman Rockwell’s interpretation of Freedom from Want—the third of FDR’s four freedoms.

The American Dream. No matter who you are, no matter where you came from, no matter the circumstances you were born into, every American is told they have the chance to build a prosperous and successful life for themselves. A capitalist society that rewards hard work with a white picket fence, 2.5 kids, and happiness. But this idealized land of opportunity is a facade. Some are born with a silver spoon in their mouth, every opportunity and resource at their fingertips. Most are not so lucky— overworked and underpaid, forced to be cogs in the machine of an increasingly commodified world. Work to want, want to work.

This shoot explores the dark underbelly of American corporate success. In the setting of a 1980s Wall Street office, three successful corporate workers ungracefully face the everyday monotony and stress of work life. Muted colors, brutalist architecture, anxiety, and exhaustion. An exploration of what happens when want becomes need, and when desire turns into greed.

Rachel Yu

America sustains a work culture where people work arduously and strain themselves for one common goal: wealth. There ultimately lies a heightened sense of pressure on individuals to pursue certain career paths, like medicine or law, in order to monetarily align with the ideal American lifestyle. But this shared goal of wealth is uncertain — we’re not guaranteed it, no matter how hard we work.

With values and ideals like the “American Dream,” we are constantly told to strive for our dreams. But if your goal isn’t to be a lawyer, doctor or entrepreneur, then the traditional notion of a “dream” instantly becomes unrealistic and unattainable. As the gig economy heightens throughout the United States, there is an underlying sense of pressure to put a well-paying, six-figure job before your dreams for the modern definition of the “good life.” But what exactly are we working so hard to achieve beyond just money?

The gig economy drives us to want more than we already have, it compels us to become greedy. We are constantly in search of newer, stronger opportunities, ones that would provide us with the sense of fulfillment and satisfaction of the opulent lifestyle we yearn for. People constantly post pictures of themselves and their material possessions on social media as symbols of status, showcasing their ability to thrive in the gig economy. Extravagant vacations and luxury goods serve as a beacon of pride. But the sense of fulfillment people receive from an opulent lifestyle is never enough, as we are never satisfied, as the American corporate culture trains you to constantly take rather than

give. These 40-hour work weeks and 9-to-5 schedules train us to go to extreme lengths to reach a certain hierarchical state. We gain nothing from this cycle other than money.

This sense of greed and envy generates greater dissatisfaction among us. In America, we are confronted with the realities of a dissatisfying economy, which ultimately intensifies competition among everyone. When given the privilege to reward ourselves for hard work with a luxurious lifestyle, we tend to exploit that power and privilege to see how far it can take us. But once you reach that sense of comfort and an idealized wealth, will you truly be content?

Of course, I acknowledge that working is a necessity in American culture—you need to work to get by and bring stability to your life. As a college student who hasn’t even entered the corporate world yet, I completely understand that money can be a powerful and compelling force behind the drive to work.

But we are constantly striving to show that we are doing so much better than we actually are. We desire an idealized image and reputation of ourselves, especially on social media platforms, to display and show off our material goods and the lifestyle we’ve built for ourselves.

People work so hard in American corporate culture, only to feel dissatisfied and compelled to display a “perfectly picturesque” lifestyle. It makes me question whether the American Dream is truly rewarding in the end.

Esmeralda Moran

Shampoo squelches between my mother’s fingers as she works them into the woman’s scalp. This is her fifth client within the past hour and the dryers are all taken. It’s a busy day, but a busy day is better than sitting around in an empty salon waiting for someone to walk in. In another lifetime, she would have gone to college and studied computer programming like she wanted to. In another lifetime, she would have accepted the offer to play nationally for the women’s volleyball team in the Dominican Republic. In this lifetime, she is confined to a 9-to-5, more like an 8-to-10 or 8-to-12 if things get busy.

In this lifetime, there was no privilege of generations spent in the United States, roots already established, American culture embedded in our blood. Here we are still naive, an eyesore to the public already calloused by the brutal truth of the American Dream. The odds were never in my favor, it seems.

As the first in my family to live and breathe under a different red white and blue flag, I’ve realized the jarring difference in the way I’ve grown to interpret opportunity compared to the rest of my family. Opportunity to them, no matter how impossible it seems, is still obtainable. To them, the streets are still paved with gold and Lady Liberty opens her arms to all, excusing their shortcomings in exchange for blind hope that something better will come their way. Whereas through the cracks in the streets, I only see a reminder that what was once a possibility is now long gone.

The reality that my upbringing can determine how the world will treat me is a punch in the face. Despite being born in America, my class, physical appearance and mere existence will be a deterrent to achieving any semblance of a normal life. In spite of this harrowing realization, I keep moving forward, knowing that my situation is far better than what either of my parents went through in their lifetimes.

My privilege is born of guilt. My qualms about an 8 a.m. class are nothing when I think of my mother, who worked on a tobacco farm from childhood to age 20. Groaning at the mountain of homework piling up is inconsequential against my mother’s experience being left in the Dominican Republic while my grandmother immigrated to the United States alone, unaware that she could have brought all her children over rather than waiting two decades to be reunited with them. My trivial complaints dwindle to nothing when compared to the struggles my mother endured, only to fall short of the dream she was promised, still living a life of hardship.

While rinsing the shampoo out and reaching for a bottle of conditioner, my mother never fails to mention how proud she is of me to anyone within earshot. The first to attend college, the first to go to a private college, and the one who will succeed, she says. These words linger in my ears and remind me that I am more than my shortcomings. Yes, the odds are stacked against me and yes, I know that it will feel like I go through more setbacks than steps forward, but I am accomplishing something more important than anyone could anticipate.

The moment my mother came to the United States and reunited with her family, she was finally given back the normality of being with the people she loved most. When she had me here, she promised never to abandon me or to let me struggle as she did. It was channeled through her constant berating: looking over my shoulder as I wrote homework in the language she couldn’t comprehend, showing up to parent-teacher-conference and nodding fervently as I translated the high praises my teachers gave me were proof enough of this promise. Her feelings of anger and betrayal when I told her I wanted to go to school in Boston, her breakdown upon realizing that we would have to pay $1,000 per semester, an amount we couldn’t afford, and the hundreds of calls I was forced to make in order to ask the school to consider lowering that amount because we live below the poverty line.

Despite the gutting feeling of embarrassment and painful awareness of the possibility of being unable to attend the school I spent every effort to get into because I couldn’t accumulate a month’s worth of income in less than two weeks, I continued to advocate for myself at my mother’s request. Her feelings of relief, joy and pride that her daughter would be going to college were unforgettable. The fighting had worked out and I’d be going, achieving a dream my mother never had the chance to do. When my godparents drove me to Boston to move in, because she couldn’t risk closing the salon for a day and losing money, I realized that the American Dream she always talked about was not an abstract idea–it was me.

The American Dream comes in many shapes and forms. Some are owning a home, some are becoming rich, some are moving up in class. The fact that I will walk across a stage with a red robe and black cap is more than enough for my mother. She continues to open her salon at 8 a.m. every day, enduring the fumes of hair dye and blow dryer smoke, happy to know that I have a “normal” American experience.

ELLIE WATSON

BEAUTY

STYLE: CAPRI BOLD, SOPHIA TIERNEY KATIE ENGLAND

MODELS: NICOLE LEE DAVID FILS-AIME LUDOVICA PUKIA

SOCIAL MEDIA: TRACIANNA WALCOTT

KAYLA BALTAZAR HANNAH LASHIN

MADISON LIOYD

PAGE LAYOUT: ALICIA CHIANG NAOMI COHEN BELLA BOHNSACK

Commercialism, materialism, and consumerism. Can’t beat ‘em? Join ‘em. Adidas sneakers and Burt’s Bees chapstick. A bright red guitar and glowing lava lamp. Star Wars key chains on black coach bags. These are a few of our favorite things.

Shot on the twenty eighth of September twenty twenty four at 42.345670, -71.118670 for issue 06 of Strike Magazine Boston’s “Faded Glory.” Editorial design completed by Alicia Chiang, Naomi Cohen, and Bella Bohnsack.

Two parents peacefully tuck their children into bed. The father holds a newspaper donning “BOMBING” and “HORROR,” but his attention is on only his children. His face is not full of worry and dread but is painted with tenderness and love. This is Norman Rockwell’s interpretation of Freedom from Fear, the fourth of FDR’s Four Freedoms.

Unlike the depiction in Rockwell’s painting, living without fear in the modern-day United States is a luxury. Minority groups, people of color, women, trans individuals, and many others still face unacceptable levels of hate and violence, making living without fear an aspiration, not a reality. While living in the United States is a blessing compared to other parts of the world, it is crucial to point out where we can improve. Today, people still feel fear, even in places where they should be the safest, like homes, schools, and even walking down the street.

This shoot examines the question of What would it be like to live without fear? It is inspired by the works of Black Mirror, specifically the episode “Nosedive,” where everything is a bit too good, everyone is a bit too happy, colors are a bit too bright, and smiles are a bit too large. However, a dark reality lurks beneath. This interpretation of freedom from fear aims to capture this idealized vision of the United States that people often hold in the back of their minds: big smiles, lawn chairs, coke on a sunny day, without a care in the world.

Altea Peyser

Finding myself outside an abandoned house in the hills of Northern Italy, I had no idea I was about to time-travel and connect with the Earth in a way I had not in years. Standing in prickly late summer grass, my lanky 17-yearold self felt so distant from my childhood self; the little kid who played in nature, climbed trees, and made homes for fairies; when nothing stood between her world of magic and the ground on which she stood. Time held no meaning until childhood drifted away, and adolescence made way for a colder world.

In the blur of adolescence, I emerged into a world where my homework existed on a two-dimensional screen. I had disconnected from myself, a little girl I held within.

Ecstatic dancing, a rehumanizing experience, broke down my barriers and enlivened a familiar magic that existed between utter presence and the warmth of the earth becoming one with my swaying body.

As the sun drifted lower and lower, I curiously waited, surrounded by strangers, a DJ, our warm leader who sought to bring this Indian meditative art form to Italy. She spoke three rules: be barefoot, do not speak, and do not use any substances. The next second, I was in meditation. Free to move however we wanted, we entered something more akin to an ecstatic trance than a dance. Without the context, one might have taken this gaggle of souls for a cult group.

Sober and barefoot meant no physical limitations existed except our own. As we began, our leader’s voice echoed across the hills, and my mind went into a two-fold resistance.

The first was my judgment of those around me. The voices in my brain began to mock the older individuals, characters of all genders of whom I knew nothing, dancing alongside me. I pushed on, imitating others’ outlandish moves. Slowly, I realized my fellow dancers were all content, and that I had projected judgment for myself onto them. I thought I looked ridiculous, embarrassed of my swaying limbs, without a barre or classical ballet steps to lean on.

What came next shifted my presence, allowing me to contend only with the present moment. Entering a deep meditative state, an utter calmness overcame me, with freedom from all judgment, once binding barriers. With my fellow dancers, I grew unafraid of eye contact, crawling in the grass and hanging from the nearby trees. Still, without speaking, I frolicked with the souls of strangers, which would become intensely familiar. Time held no meaning aside from the sun sinking lower into the hills, and before I knew it two hours had passed; two hours of pure movement, connection, and present fun. Reconnecting with my inner child, I released all fears, realizing I had grown to become my biggest fear of all.

Altea Peyser

Are we truly living on this Earth, or in the flashing signals of this technological era? Today’s phones have become an escape from discomfort, numbing us from our humanness and the world.

Our lives have changed. Once in a direct relationship with our environment, we are now occupied in conversation with our smartphones, ominous omnipresent encyclopedic cameras. Politicians tweet from their toilets and tragic news comes to us before our morning coffee. Apps are designed with gambling tactics, feeding into algorithms and breeding our addiction to the screen. For dopamine hits, we talk, shop, eat, and meet online, expecting more and more. But are we stopping to consider what it all is, what lies beyond the chronic flow of media streaming past our gaze? Do we look and dance with what stands right before us?

We navigate the present with oversaturated information and perspectives, detracting from the joys of deliberation and speculation. Answers to simple questions are at the tips of our fingers. Last Saturday afternoon, for example, I craved a good cinnamon roll, and before I could suggest asking a friendly neighbor, my friend exclaimed, “Here we go!” She had googled “bakeries near me.” We had been

conveniently led straight to a bakery, following an arrow on the screen’s moving map; our senses made to be engaged in five different ways and absorbed into a single screen. Any sense of risk and ambivalence vanished from the venture to find a treat. I had no incentive to chat up my neighbor or stop to consider other food alternatives. Who knows what words could have been exchanged in a conversation with my neighbor, or whether we would have discovered a new treat, possibly more delicious. We became estranged from a small moment that might have enhanced our humanness. That momentary experience would have resulted from thousands of years of evolution without this device. A majority of today’s science is based on smart human brains, not smartphones.

What’s the effect? How is the phone rewiring our brains, thinking, and notions of self? Do we know who we are when rushing through life, absorbing reflections of our images all the time, music streaming through our ears, and echo chambers of the internet splashing across our minds 24/7? Is this device alienating authentic human nature and stripping us of our connection with the natural world? Maybe we’d see the answer if we set out without our phones. The present might taste as sweet as a warm cinnamon roll.

PHOTO: BELLA OLAND, PABLO GONZALEZ

BEAUTY: SARAH-EVE GAZITT, MARIA FISCHER

VIDEO: DYLAN RECORD, TYLER HOM

STYLE: SOF MARTINEZ, SHANNAH VIRIVONG, CHLOE ROWEN, CAPRI BOLD

MODELS: AVA MOLLOHAN, ELIJAH CARRION, CAPRI BOLD

SOCIAL MEDIA: TRACIANNA WALCOTT, JEWEL SILVA, MADI LLOYD

PAGE LAYOUT: ALICIA CHIANG, NAOMI COHEN, BELLA BOHNSACK

Shot on Polaroid Now Gen 2 Camera with damaged i-Type film. The film was damaged going through airport security scanners as I was traveling to Ireland to spend Christmas with my extended family in December 2023.

Growing up in America, visiting my extended family in Ireland every year has always been a special experience for me and I constantly associate the holiday season with community and spending time with family. These polaroids capture the warmth of being in my aunt and uncles house on Christmas eve and Christmas day, and the airport x-ray damage on the i-Type film leaves a mark on the images that signify the lengths that my family and I go to just to celebrate the holiday’s with those closest to us.

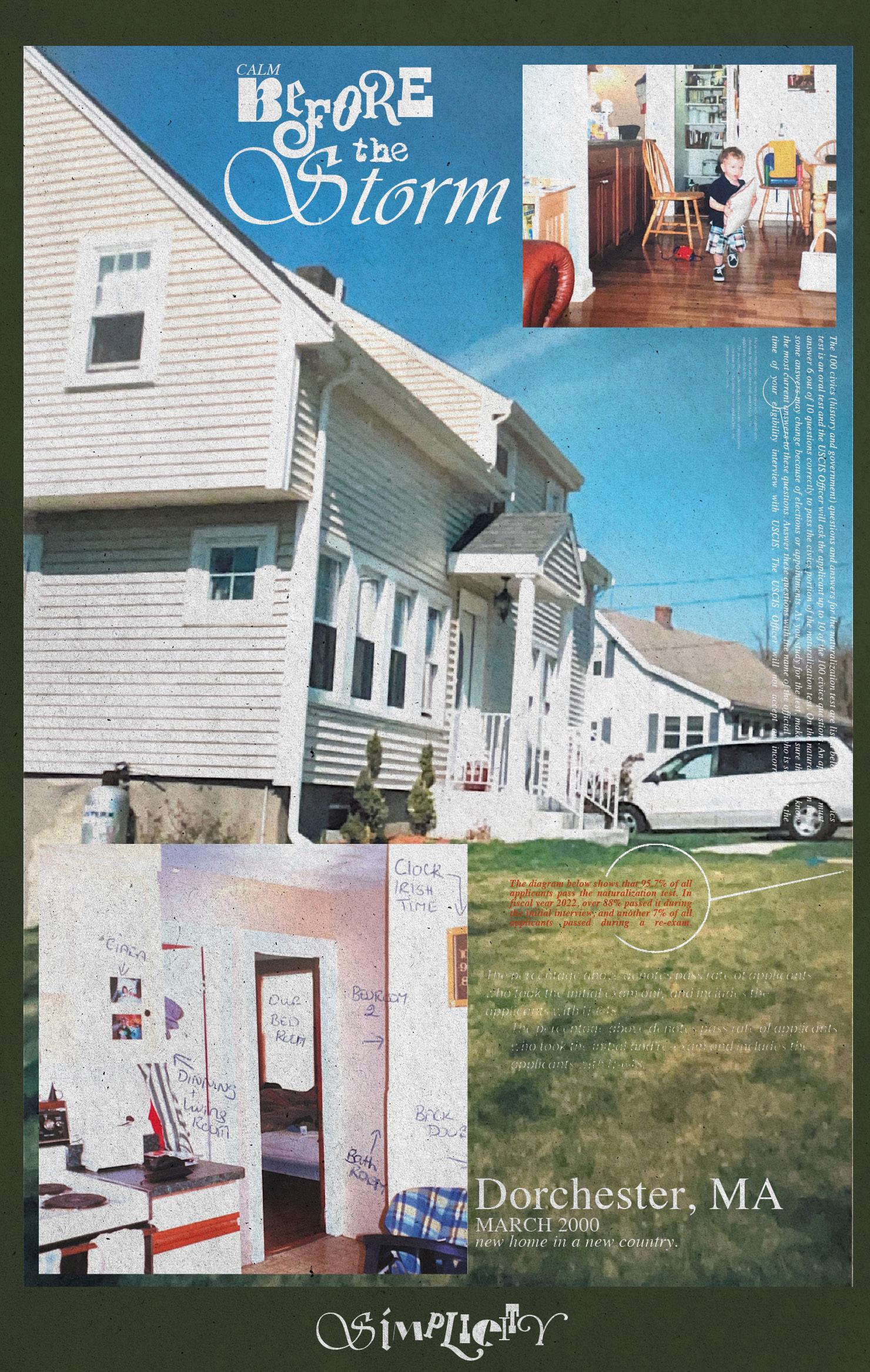

Created in November 2023, this piece takes inspiration from my parents experience moving to the United States in 2000 to start a family in a new country. Full of opportunity and hope, my parents built our lives from the ground up starting in Dorchester, MA. The title “Calm Before The Storm” comes from the stillness and simplicity of my parents lives prior to raising four kids far away from the place where they grew up.

The piece features distorted text taken from the US naturalization test, a process that my parents and oldest sister underwent in 2016 — 16 years after moving to this country. The typography on the piece features mismatched typefaces spelling out “Calm Before The Storm”, representing the diversity of cultures and experiences that Dorchester, MA contains.

I’ve always been drawn to a patchwork type pattern, I knew I wanted a variety of different prints and fabrics on the jeans. The Delray Beach fabric panel was taken from an old shirt from the annual surf festival that happens in my hometown, keeping the piece authentic to me.

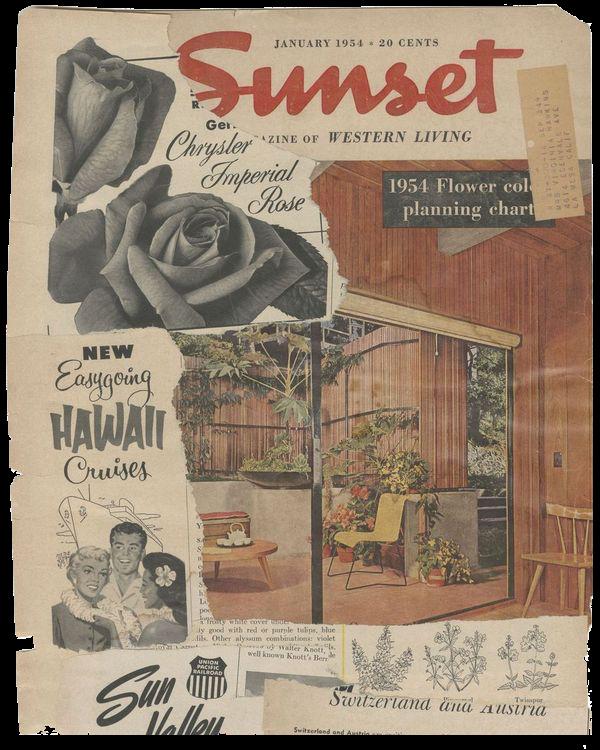

My handmade collages breathe modernity into fragments of carefully sourced 1940s magazines. By deliberately juxtaposing vintage images and textures, I craft abstract compositions that serve as a deeply personal expression.

These pieces are meticulously organized to create a visual narrative that bridges nostalgia with contemporary artistic vision. By reimagining these vintage elements, I invite viewers to explore the intersection of past and present, evoking a sense of timelessness that resonates with the audience.

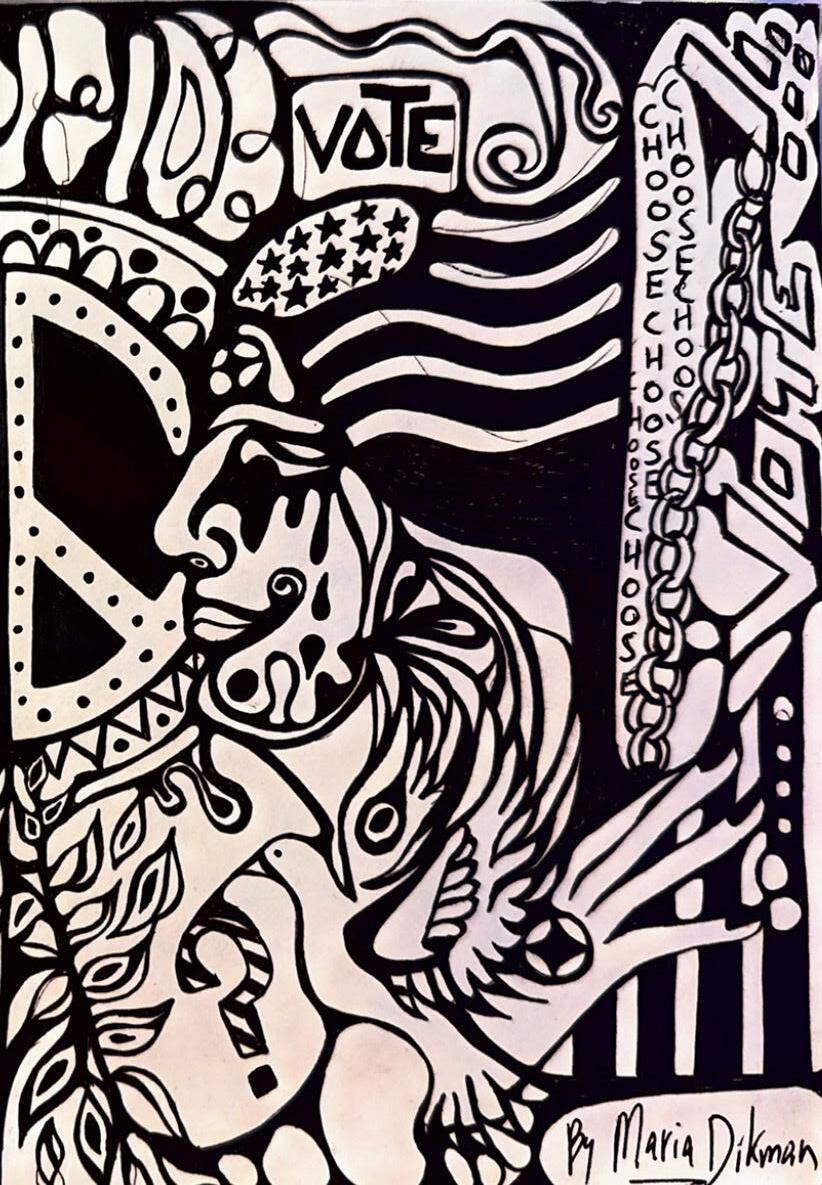

We all fight for a piece of the cake, yet deep down, we share a longing for peace— perhaps the only thing that truly matters.

This artwork delves into the relentless tug-of-war of election season, where we fiercely champion one side, but beneath it all, peace is the ultimate pursuit.

STRIKE OUT.