To Care

Article 1 Article 2 Article 3 Lust Article 1 Article 2 e Anarchy Issue Article 1 Article 2 Article 3 Extravagance Article 1 Article 2 Article 3 Article 4 Credits Advertisements

Obsession has always been misunderstood.

When we imagine our obsessions, we think of beauty, of money, of fame — all are desired, but ultimately become sources of addiction and harm, double-edged swords. Obsessions are insa tiable; we reach for them, they hurt us back, we reach again. It’s an endless chase, often for the worse. Too much, it seems like, is a bad thing.

But what would a world without obsession look like, feel like, sound like? We asked ourselves: would it be worth living in? What if we em braced obsession to the fullest, if no vice or fas cination was too outlandish or indulgent? What about when obsession becomes inspiration, and the chase becomes creative? Rather than always reaching, you gaze, and create what you yearn for while inspired by the beauty you see.

We want to reimagine Obsession, to nd the point at which too much becomes good. We hope Issue 03 will expand your perception of obsession and leave you wanting more, so that you create more.

WRITING DIRECTOR

Helenna Xu BLOG DIRECTOR

Natalie Daskal

CONTENT EDITORS

Mary Clare Cameron

Katie Sharp

WRITERS

Maddie Arruebarrena

Mae Brennan

Isabelle Grassel

Connor Marrott

Jane Miller

Cameron Oglesby

Elisabeth Olsen

BEAUTY DIRECTOR

Alexy Monsalve

MAKEUP ARTISTS

So a Gomez

Skye Sharp

DESIGN DIRECTOR

Anna Kulczycka

LAYOUT ASSISTANTS

Annie Brown

Devlin Hose

Christina Sayut

GRAPHIC ART ASSISTANTS

Sydney Ellis

Kyla Goksoy

Brian Johny

When people ask me “Why Notre Dame?” the answer is always, “Strike.”

When deciding where to go to college, I found out about this magazine from a friend, and I knew this was where I wanted to be. Since then, being a part of this community has been one of the most profound experiences of my life.

ank you to each and every person who’s been a part of Strike; your creativity and trust in this team have helped create the piece of art that is Issue 03.

To my parents and friends, I’m beyond grateful for your constant support and for being a source of inspiration.

ank you to Taylor, Katelyn, and Ryan for being my workwives and making this semester so memorable.

To Trinity, thank you for helping create such a special place where I

Strike is an incredible outlet for expressing creativity and culture in the busy world we live in. It has been a pleasure for me to take part in the process of creating Issue 03. ank you to everyone on sta and all models for helping make our vision of e Obsession come to life.

To Gracie and Ryan, thank you for convincing me to join Strike. I am so grateful that I got to be a part of this community and see your creativity in action.

Taylor and Trinity, your hard work and dedication to Strike is so inspiring. ank you for making my experience with Strike one to remember.

Strike out,

or the past three semesters, Strike has been our way of spreading and cultivating creativity on campus, sharing our love for fashion, art, and writing. We are beyond grateful to have had the opportunity to connect with our sta and express our creativity, shining light on all that Strike o ers. It’s always exciting to work towards the nal print issue, but the community of students we have created is what we truly work towards, and we cannot wait to see what the Strike community has in store for the future.

Creating a magazine is no small task; it’s an experience like nothing else, and it often goes wrong. It was a semester of

When deciding to attend Notre Dame, I hoped I would nd a creative community to be a part of and to express my passions. As soon as I discovered Strike, I knew I had made the right decision. Having the opportunity to be a part of the Strike community has been my favorite experience at Notre Dame. From each and every shoot to the hours of ed iting and design work, I could not be more thankful to be surrounded by such a passion ate group who strives to bring creativity to our campus.

ank you to each person who has made Strike possible and allowed us all to express our creativity in our unique ways. To Gracie, Katelyn, and Ryan, thank you for your constant support and positive energy throughout this semes ter. To my parents and friends, thank you for your encourage ment and listening to me talk about Strike 24/7. And to Trinity, I cannot thank you enough for believing in me and allowing me to work by your side this semester as Co-Editor-in-Chief. ank you for bringing Strike to campus and leading this creative community.

Strike out,

brainstorming, working, then reworking (a lot of reworking) to ensure we created something everyone is proud to have worked on. At every concept meeting, tting, fundraiser, business call, photo shoot, and more, we consistently embrace the excitement our sta brings. It kept us going, always reaching towards this copy: a nal product that makes us all proud, one we all celebrate, one we’re all obsessed with sharing!

To Emma Oleck, thank you for being a constant source of joy and support. Your passion for Strike is and always will be an inspiration. To Gracie and Ryan, we never fail to be in awe of your innovative creativity and are so thankful to have

had you by our side, creating our world of Obsession. To Katelyn, thank you for your persistent dedication and ability to keep us on track with everything other than shoots that keep this magazine run ning. To our dedicated sta , thank you for committing your time and creativity to every role you ll. Your talents and e orts allowed us to create such a special issue of Strike, such a welcoming com munity this semester. is issue is only possible because of you.

As you explore our third issue, we hope you become immersed in our world of Obsession and fall just as in love with Strike as we have.

I’ve poured hours into the two issues I led as co-Editor-in-Chief. By now, anyone can assume the answer if they ask what I’m working on: without fail, it’s Strike. I’ve de nitely spent too much time on this issue. But how could I not? ere are so many moments of beauty scattered throughout the process: seeing a rsttime model’s face light up as we show her photos during a shoot; watching an article evolve from idea to draft to work of art; looking around at the launch as people eagerly ip through pages that are the culmination of their hard work. We took too many photos, spent too long editing layouts, and we’ll probably get too excited at launch. So, is too much a good thing?

I hope the answer comes in the pages that follow. I’ve spent the last three years trying to grow Strike from an idea to a community — and I wasn’t alone. ank you to eresa and Taylor, who were always by my side, to Gracie, who led this issue where it needed to go, to Matt, my ever-con stant source of support, and to my family for encouraging me that

Comparison is the thief of joy, they say. It’s still the rst place my mind goes — and I’ve gone there often. I think I’ve been rejected from most of the things I’ve ever applied for in college. Every time, I care so much; I can’t help it. It comes like a gut punch, when you read the email: ank you for your application, but… en I’ll hear about someone else, who did get it, and I’ll imagine what it would have been for me, torturing myself with what I could’ve done di erently, how I could’ve changed a sentence’s phrasing, when I should’ve said something smarter.

I feel like I’m drowning in cares, like everything matters so deeply and I feel it all in the center of my heart, every rejection, every missed opportunity, every time I let something slip through my ngers. It all leads towards the future, making a ‘what could have been’ rather than ‘what is.’ e funnel of life, my dad calls it. Every decision we make sends us slipping an inch further down the funnel, until there’s only one path in front of us, which we have to follow. It matters what path I end up on, I tell myself. To be happy, to have money, to make the people who love me proud enough. Other people seem like they’re doing it all; how do I not compare, when they get something I wanted so badly? I would have to not care.

I’ve tried caring; I haven’t tried letting it go. Would it be freeing? At rst, the idea feels delicious: to oat, as if on the ocean, letting waves of happenings wash over me. It doesn’t matter if I don’t get it; it doesn’t matter if I do. e path the funnel leads to is

simply a path. No one is better than the other; I’m not more passionate about one over another. I could oat through these formative years, without getting upset, without regret, without jealousy. Without care.

Gray with indi erence. Better than green with envy, I suppose.

en what, though? Indi erence would infect my life. Not caring about the bad, about what I miss out on, about what I lose, means I would eventually stop caring about the good — what I love, what I depend on. I could nd myself in a place I used to dream of, and it wouldn’t matter. Obsession disappears and with it so does pain, but passion follows. My heart wouldn’t be hurting, but what would it be?

So it’s worth it, I guess — to care. It’s a ne line we have to walk: to care, without comparing, to let everything matter without succumbing to it all mattering too much. To nd something between drowning and oating. I’m hoping that the funnel makes use of all this rejection and leads me to a path I love, one that inspires me to obsession. If not, though, maybe I’ll learn to care so much that I push out of the path I feel forced into and create one that I love to the point where I no longer compare.

By Trinity Reilly

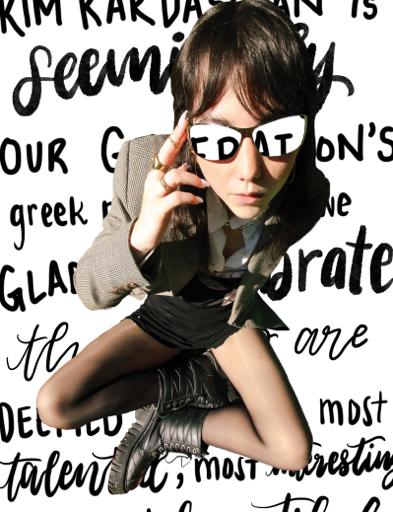

The rise of Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram has allowed us to consume the daily life of a celebrity at an alarming rate, using their stories to help make sense of our own. In the 21st century, it is impossible to deny the reliance we have placed on celebrities to navigate an increasingly confusing world. Social media has allowed celebrities to insert themselves in almost all facets of existence, from how to bake to how to navigate international politics. Such in uence is now broadly accepted as the norm. Whilst sometimes conducive to society, celebrities have in ltrated our lives in one form or another, and this relationship remains troubling for both the celebrity and the audience. Our exposure to celebrity culture has led to a shocking rise in low self-esteem.

With clinical precision, celebrity culture has induced a “picking-apart” approach as we poke a hole in the illusion of perfection and thrive on the pleasure of seeing others’ misfortune. Accounts attracting millions of followers dedicate a large portion of time to playing the celebrity surgery sleuth. is desire to lift the veil for transparency in the hope of improving self-esteem often does more harm than good. Despite this love to dissect the bodies and faces of those in the public eye, this “before and after” mentality does not improve body image issues and is detrimental rather than bene cial.

Both celebrities and their audience are impacted by the dissection of “perfection.” Celebrity culture remains a strict observer of a beauty ideal. Celebrities are forced to conform to impossible standards of beauty. Taunted and shamed for imperfections and vili ed when attempting to live up to these standards, there is an impossible standard of beauty exacerbated by celebrity culture. Supported by the media’s microscopic lens, there is a “damned if you do, and damned if you don’t” approach.

e way we relate and respond to celebrities has a signi cant impact on celebrity and audience well-being. When we start perceiving celebrities as a combination of physical parts that one can judge, there is a tendency to treat people in our lives as well as ourselves in the same manner. Whether it be through

the screen of a mobile phone or a mirror, celebrity culture has encouraged us to analyze, examine, and diagnose every detail of ourselves. We have trained ourselves to be hyper-aware of every fault and feature and fail to acknowledge the main purpose of the human body is not “aesthetic.”

e rise of modern technology has turned celebrity worship into a billion-dollar industry. Each year, millions tune in to watch the Oscars, to scrutinize performances, out ts, and acceptance speeches. We have become unapologetic celebrity addicts, a trait endemic to humanity.

Human beings have always worshipped. Historically, this was the gure deemed most special in society — the best hunter, the best athlete, the most beautiful, and the most spiritual. Earliest societies had celebrities, the Ancient Greeks cherished its thinkers, and we ock to beings of in uence who apparently possess the solutions to all of life’s problems.

Kim Kardashian is our generation’s Greek philosopher as we gladly celebrate those who are deemed society’s most talented, most interesting, and most beautiful. We develop deep bonds with celebrities as we immerse ourselves in their lives, emulate their style, and lay witness to their mistakes and mishaps. Whether we know them personally or not is irrelevant. is bond with our favorite stars is constructed from envy, admiration, and borderline obsession.

We seem to mistake an all-encompassing knowledge of celebrities for genuine intimacy. e infatuation with the rich and famous provides a release from the often monotonous life the everyday person leads. Celebrity culture has given a false sense that we know those we see on the screen, ampli ed more so by the label of “reality” applied to those in the public eye. ough the great personas of yesteryear have been replaced by actors, socialites, and billionaires, the obsessive plague with celebrities persists.

By Mae Brennan

If I could tell you that you live brightly within my waking mind that we walk daily together through rose gardens, and laugh over burnt pots of home-brewed co ee that you have burned yourself into the constellations and converse, teasing, on the drive to work — Would you believe me?

(I know we don’t speak.) Would you smile softly as if to say of course, you were there too?

I think we should agree to keep stealing away together to that dew drenched rose garden at midnight our sacred realm of secret rendezvous where our patiently repressed joys blessedly break forth in sweet laughter. We are quite ingenious, you know, to have found this place outside the fetters of time and space. such detail is burdensome — a million lives can be borne by moonlight and memory. someone said once that time past and time future all fold over in an eternal presence. the romantics know not to imagine undue nality in what has happened — ephemeral truth resists our vain e orts to inter it with stone tombs of the past.

You left me, I know. I know. what was called us ended years ago. but an us will never truly end — it births an eternally present world of memories and endless echoing corridors what could have and would have been stand like mirrors and the same rains will fall again and again.

you have burned yourself into the constellations and its blazing brightness inscribed your hazy shape on my retinas. you smile at me knowingly (these secret spells are never said). you will meet me there tonight, I am sure.

By Mary Clare Cameron

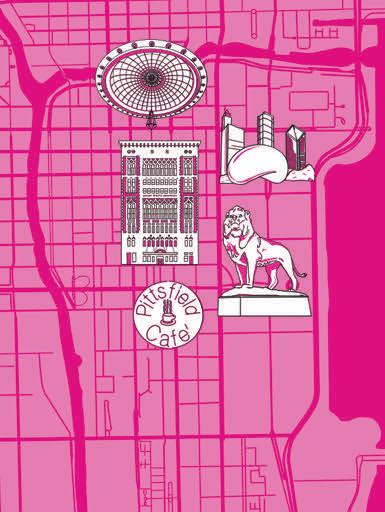

I am at school right now, and I feel kind of lost. e stress from expectations to achieve and juggling between relationships is overwhelming, and I never seem to get anything right. I think of how I have never felt freer than when I’m in Chicago, and this tender nostalgia always brings me ease.

I remember when I went on a date at the Art Institute. e anticipation was driving me insane, but my familiarity with the city comforted me, made me feel as if I could blend into the background and just disappear. But seeing him ended up being the best part of my summer, and I know the city itself was part of the reason, with the brilliant sunset on Mag Mile and the unique smell on the Red Line. Perhaps I no longer talk to that person anymore, but I won’t forget how we wandered together in the galleries purposelessly, catching each other’s glimpses.

I also miss the time when I could walk to a co ee shop on a summer day. Interactions with strangers were not anxiety-in ducing but rather warm like the lakeside summer breeze. No one cares about what I’m wearing. I see everyone through their eyes without having to read their intentions. I couldn’t help but smile when the cashier remembered my order, realizing how far a little extra e ort could go. e co ee tasted like magic. I took a little more time on each sip instead of gulping it down in the morning before class. Often at school, I struggle and race with time and could never catch up. But at this moment, I was breathing, and time was sitting in my hands, rather than slipping through my ngers.

But I would be lying to myself if I said Chicago is perfect. When I talk to my friends at school, it makes me sad when people’s rst reaction when Chicago is mentioned becomes fear and resentment. But their feelings are justi ed, because gun violence creeps into every neighborhood, and the loss of life is unacceptable. I can’t go to the art museum or my favorite co ee shop if I don’t feel safe. And these moments where you fall in love with being alive should be available to everyone.

I don’t want anyone I know who lives in Chicago and the greater Chicago area to lose their sense of belonging. I treasure all the streets I’ve walked, all the memories at high school proms, and all the night sky’s neon lights. I don’t want to always be watching my back when I leave my house, and no one should. ere has to be restoration, perhaps long-awaited change. Until a sense of security is restored for everyone, it’s not enough.

But I’m not going to stop loving Chicago. Loving a place is like loving a person. Loving is not ignoring all the aws and pretending they don’t exist — it’s recognizing and acknowledging them and seeking the solution to grow with this place, this person. I’m pursuing higher education to give back to the people and place I love. I want you, whether you’re from Chicago or just visiting temporarily, to feel the repose and spontaneity Chicago has gifted me. Chicago, I will not turn my back on you. I love you.

Strike Out,

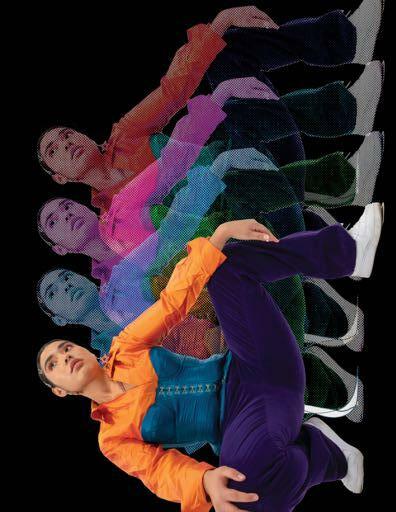

(noun) an intense longing: craving.

Green light.

My desire is like a hunger that can never be satiated. It is a relentless hunt in which I can never seem to run fast enough to catch my prey. With every hour I get a little faster until I am just an arm’s length away from my x ation. Extending my arm beyond its reach, straining my shoulder, stretching my ngers as straight as they go, I can just barely feel it graze my ngertips as it falls short of my grip. is chase turns into an obsession. I wake up with an intense feeling of deprivation — my empty stomach growling with a hankering for just this one thing. I can smell it. I swear I can even taste it. At this moment my senses can not be entertained by anything else. is hunt is all-consuming.

Yellow light.

Today I nally catch my prey. And then tomorrow I will catch it again. I am not sure if it slowed down or if I sped up, but I no longer spend every day engulfed in a chase, hoping I get close enough just to touch it. Now I can feast on it whenever I want. My appetite is satiated — although it seems to grow smaller every day. My senses become immune to the familiarity of the taste, the smell, the feel. e excitement of that rst touch begins to fade as the object I am chasing begins to feel like it is my own. I no longer ache when it is not within my reach. And I begin to miss that ache. I miss the way it consumed my every thought, directed my every movement, lled up my lungs with every breath.

Red light.

I no longer wake up with a craving for more. My desire — driven by mystery, excitement, obsession — faded with the same intensity as it began. is desire drove me to run; now I stand still and wonder why my feelings faded. As I chased it, it felt like I could not stand to be without it at that moment. When did it lose its allure? And why didn’t it develop into something more, something deeper? As I ran and ran, my feelings were intense, vibrant, felt in every nerve as my feet hit the ground. And now I feel nothing. is all-consuming chase took everything out of me, and now I am nothing at all.

By Katie Sharp

roughout American history, fashion has always been used to signal political identities. In the 1970s, Saint Laurent’s pantsuit gave a uniform to the sexual liberation movement, in the early 1900s, purple was donned by the su ragettes to covertly beg for enfranchisement, and in the 1960s, conformity-breaking leather jackets sported by the Black Panther Party be came an extension of their radical politics.

Fashion o ers a unique method of dissent: a way to convey political messages, marked by acts of activism and struggle, with clothes that empower the wearer. Fashion has allowed for dissent to be ingrained into daily life, con stantly reminding society of who we ought to be. But fashion today has lost its radical roots. Fashion no longer acts to subvert authority by breaking conformity; rather, it has turned into a commodi cation tool to pro t o of social activism.

e commodi cation of social movements in fashion is just one symptom of the American parasite of capitalism. Companies like Tar get, whose annual revenue in 2020 raked in over $93 billion, have manufactured clothes, dishware, and home goods with pride ags, and Walmart, whose annual revenue in 2020 raked in over $559 billion, manufactured Black Lives Matter t-shirts ever since the murder of George Floyd. Distributing this ideology through products and fashion seemingly ampli es queer, BIPOC, and feminist social issues. However, the brands that manufacture “activist” clothing

merely create a facade to protect capitalism’s reputation.

Since the 2010s, feminism and other forms of political activism have become popu lar among consumers, encouraging brands to commodify activism for capitalist gains. Activist commodi cation refers to companies that shift various activist movements away from their radical beginning and towards cultural performanc es, like wearing clothes. e radical anti-institutionalist messaging in earlier protest fashion now has become lost because activism has been commodi ed. Iron ically, activist fashion now con rms and strengthens the various economic institutions that activist fashion originally fought against.

is commodi cation of activism is a way for companies operating in capitalist economic systems to exploit consumers; as progressivism remains popular among the growing consumer base of Gen Z, marketing products associated with radical ideologies seems like a natural way to expand the fashion industry’s consumer base. Walmart, Target, Urban Out tters, and

countless other popular fashion companies are not designing clothing with radical messaging because those companies believe in radical, anti-institution alist activism; these brands are selling radical messages because they know it will sell.

In reality, it is the capitalist economic system that actively works against true liberation for all people. When we buy into commodi ed activism, our money signals to power that we are will ing to ignore labor exploitation. Capitalism, to which nearly every social issue can be traced back, wants to distract you by selling a “Black Lives Matter” or “Destroy the Patriarchy” t-shirt.

Brands commodifying activism for economic gain code to the public that wearing certain clothes is the de nition of activism, ignoring the hope of true gender, racial, or sexual liberation. Fashion used to be a legitimate expression of radical politics; now,

however, capitalist institutions produce “radical” clothing that depoliticizes movements. Being part of a movement no longer means protesting, calling your representatives, or volunteering through grassroots activism; being part of a move ment, now, is about what’s in your closet. No one is individually culpable for the creation of performance activism. Rather performance activism is a trend carefully crafted by the capitalist economic system, which coerces the wallets of Gen-Zers into spending more money.

So, before you buy that shirt for pride that’s hanging on the rack in your local Target, ask yourself: who is this for?

Shouldn’t our clothing be supportive of the marginalized communities we want to liberate? Shouldn’t our clothing re ect true anti-institutionalist activism? If we want to use fashion as a method for dissent, we cannot give into the facade of liberation that capitalism has created by commodifying activism.

By Connor Marrott

,,

The rules keep us in order. The rules keep us from doing the wrong thing.

The rules keep us in order. The rules keep us from doing the wrong thing.

The rules keep us in order. The rules keep us from doing the wrong thing. The rules keep us in order. The rules keep us from doing the wrong thing.

The rules keep us in order. The rules keep us from doing the wrong thing. The rules keep us in order. The rules keep us from doing the wrong thing.

The rules keep us in order. The rules keep us from doing the wrong thing. The rules keep us in order. The rules keep us from doing the wrong thing.

The rules keep us in order. The rules keep us from doing the wrong thing. The rules keep us in order. The rules keep us from doing the wrong thing. The rules keep us in order. The rules keep us from doing the wrong thing. The rules keep us in order. The rules keep us from doing the wrong thing. The rules keep us in order. The rules keep us from doing the wrong thing.

The rules keep us in order. The rules keep us from doing the wrong thing. The rules keep us in order. The rules keep us from doing the wrong thing.

The rules keep us in order. The rules keep us from doing the wrong thing. The rules keep us in order. The rules keep us from doing the wrong thing. The rules keep us in order. The rules keep us from doing the wrong thing. The rules keep us in order. The rules keep us from doing the wrong thing.

The rules keep us in order. The rules keep us from doing the wrong thing. The rules keep us in order. The rules keep us from doing the wrong thing.

The rules keep us in order. The rules keep us from doing the wrong thing. The rules keep us in order. The rules keep us from doing the wrong thing. The rules keep us in order. The rules keep us from doing the wrong thing. The rules keep us in order. The rules keep us from doing the wrong thing.

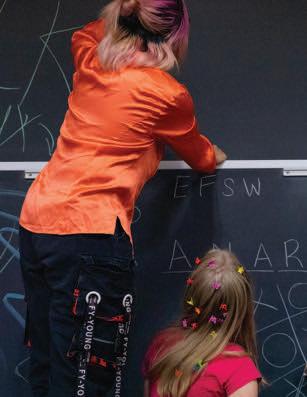

1. Gather your materials — you’ll need two pairs of pantyhose (play with colors!), fabric scissors, and a couple of safety pins.

3. Cut the feet o the panty hose. Match up the rst cut leg with the other and cut so that each leg is an equal length.

2. Cut the crotch out of the pantyhose big enough to t your head in, as you need to be able to put it on through this hole.

4. Repeat with your second pair of pantyhose.

As a child, I used to hate rules. All rules, but especially fashion rules. I simply just didn’t understand them. I wanted to wear what I wanted, and as someone who couldn’t really match clothing, this meant I was never following the rules. My mom loves to tell this story about the time when I was four and how much I loved to wear these plastic princess dress-up shoes. ey were stunning and I never took them o . My mom needed to take me to the store and wanted me to put on real shoes. ese were plastic dress-up shoes not really meant to be worn outside of the house, so her request was in no way unreasonable; however, I refused. I was determined to wear these plastic dress-up shoes to the store, and apparently, I was so stubborn that I wore them out on the town, showing them o for the world to see. I didn’t care about the rules or what was socially acceptable to wear. ere were so many occasions in which I would wear the oddest combination of out ts out of the house, and I am sure I am not alone. I don’t know if it was because picking out the out ts myself established some sense of agency, or simply because I was young and didn’t have a care in the world, but I was always happiest in these odd out ts.

However, as an adult, I feel like this sense of freedom and don’t-care attitude has dwindled. I no longer wear pink plastic dress-up shoes to the store. I try to make my out ts match and abide by these so-called “fashion rules.” I am now older and have even more freedom to act on this individuality, yet I choose not to.

is lack of insubordination and following of the rules does not just apply to fashion now but to all aspects of my life. At some point, these rules stopped becoming annoying things that we had to follow, but instead standards and norms that we chose to follow. Expectations were rst forced upon us, but we have now taken them upon ourselves. e older we got the more appealing these rules became. But at what point do these expectations and unwritten rules we have created stop acting as guides and start controlling our lives?

I often feel that I am in a state of anarchy, and it’s scary. Completely

unsure of what is next in life, and if what I am doing is right or wrong. So, I cling to the rules, hoping they will give me a sense of direction, help me to avoid the chaos. ey give us somebody to tell us what to do. To notify us if what we are doing is okay. Life feels like a state of disorder and that’s daunting. But is that any way to live? Afraid of the chaos? Afraid of authenticity?

We have to embrace the anarchy. We have to em brace the chaos.

Anarchy may seem daunting, as in a traditional sense, anarchy is a lack of authority. However, in life, when defying societal norms, the authority is you. You get to decide what your life looks like, not these imaginary rules to which we have decided to hold ourselves. We often nd ourselves held to certain standards and expectations thrust on us by society, but these rules aren’t real. Who is to say what de nes success? Happiness? Or even what is fashionable? at is up to us.

Don’t just embrace the chaos, take control of it. is is your opportunity to seize this moment. Create a space for yourself and make it your own. Channel that childlike disobedience, wear the plastic princess shoes, or better yet break the rules and make your own, and when you don’t like those, break them too and start over. Find yourself and lose yourself all at once. It’s your life to live and you can only do it once, so why follow the rules, especially ones that aren’t even real?

As adults, it can often seem that everything we do is wrong and that we need to have rules to give us some sense of direction in our lives, but only we can truly determine what is right and wrong for ourselves.

Break the rules. Break free.

Be anarchy.

By Isabelle Grassel

Do you remember your rst child hood dream?

Wasn’t the fan tasy such a rush? Does anything compare to that euphoria and such? Did you y over the earth on your own set of wings? Did you gaze down at a crowd as they watched you sing? And did you yearn for attention like I did when I was young? Have you grown and realized that attention values nearly none?

Is attention almost enough for me now, as I stand in front of a late-night crowd? Do I shine in my dress — the one chosen for the show? Do my eyes have that glimmer — that crucial model glow? Will my smile show wide on that camera lens? Will it capture my likeness in a way they can comprehend? And how can I describe this rush? Is there anything on me their gazes don’t touch?

When I step o the runway, do you miss me much? Do you want me back for just one more touch? With every touch, do I become more obsessed? Is this supposed to feel like my childhood euphoria and such? Why do you compliment me again and again? Do I truly shine as bright as you say? Can anyone feel authentic this way?

Nevertheless, should I believe the praises? Should I trust your smooth talk about my high-gloved hands and clean-cut cat eyes? What do you want from me, and

why do I want to continue to provide?

If you say I’m beautiful, why do I feel so cheap? Why am I holding my breath all of a sudden? Does this room feel smaller to you? Does “beauty” sometimes su o cate you, too?

Why am I making my way back home? Do I really wish to be alone? Why does my ego spur me to return? Will I ever learn? Do I surrender the reins, turning back to your sweet nothings and last lies? Is it too soon to miss that meaningless high? Will I ever see the pictures from tonight?

Is today the day I relive my show? Where did the elusive time go? Do I open the le or stare in the mirror all the while? Will these pictures re ect the version of me I wish to see? Why am I unsettled by an image of me? Is there anyone else I could pretend to be?

When did self-criticism become my obsession? Has attention abandoned me — left me to learn my lesson? Where did my dream go — the one I imagined not so long ago? Will I ever stop feeling this faded and ushed? Why doesn’t this feel like a euphoric rush?

Can I ask you a question?

Does this feeling of fragility ever lessen?

By Maddie Arruebarrena

Today I turn twelve. I wake up early to check if the backyard is adequately prepped for all sixty-two of my guests tonight. I passed out invitations in class weeks ago — powder pink and bordered with irides cent glitter. e waterslide had arrived this morning. Both three-tiered cakes were in position on the eight foot bu et table, waiting to be drooled over by my classmates. Impressing twelve-year-olds is easy — have food and fun and a lot of it. e more food and fun, the more people I had to call “friends.” I have come to understand the simple exchange. And my peers have come to expect a certain standard for my parties. I go back to my room and start getting ready, eager to debut the brand new swimsuit and matching cover up combo my mom had gotten me from the mall.

Today I turn fourteen. I wake up to texts from my friends expressing their excitement for the rager I will be hosting tonight. Far from a “rager,” I know this event will be an opulent display of des serts and decorations and pictures of me. e poolhouse was already dressed with several hundred pink and gold balloons. My mom enters carrying ve cake boxes full of pastries and cookies. e tubs of french fries and chicken will arrive later — along with too many pizzas — to feed over one hundred of my acquaintances. I know I will spend the evening cleaning up after my classmates and praying they manage to have a

good time without spilling on my mother’s pillows.

Today I turn sixteen. e country club is rented out and my mother has been decorating for hours already. Each lightbulb has been unscrewed and replaced with a pink bulb to match the custom neon sign that welcomes attendees. ree tables of food. ree. Gold dusted macarons and pink chocolate-covered pretzels surround both cakes. Chicken and wa es adorn the bu et table, but there are several options if you don’t like chicken and wa es, of course. ere is a photo booth where I will spend the evening taking pictures with all one hundred and fty attendees standing in high heels and a skintight hot pink dress. e tiara that squeezes my skull reads “16” in fake diamonds. I put on a smile to match the appearance of my venue and pretend to have an outrageous time. My guests arrive, and I let them eat cake.

A few weeks ago, I turned nineteen. I spent this birthday at my favorite restaurant with just my family, my roommate, and my best friend. e six of us sat around the table and laughed while we ate. Instead of the desire to present, I felt a sense of peace. I was surrounded by genuine friends who were there to celebrate our relationships. ere was no crowd to entertain, no peers to impress, no friendship to earn. My smile was real. I couldn’t help but feel the love as I looked at their faces bathed in candlelight. is was luxury. is was wealth. is was how birthdays are supposed to feel.

By Cameron Oglesby

Iwas once asked in a presentation to my class what “community” means. My peers and I instantly thought of Notre Dame and the common experiences, places and traditions that make this place so special. As a class we agreed community requires work and attention; there are certain things you do to maintain the community and your place in it. We were then asked if we considered ourselves a part of the South Bend community. Silence rippled across the class and, in that moment, I could feel the disconnect between Notre Dame and South Bend.

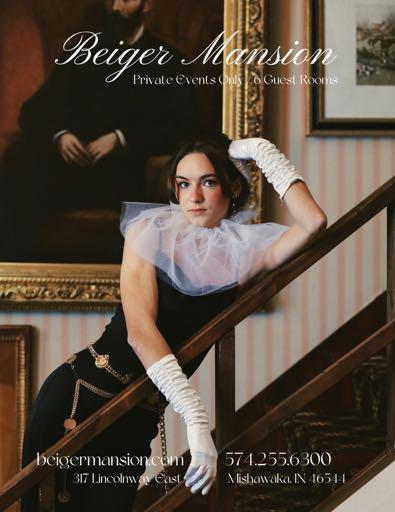

While other universities feel more connected to their college towns, it can be easy to get comfortable in the bubble that is our campus. e University of Notre Dame is located in South Bend, Indiana. e town was once a midwest ern industrial hot spot where many ma jor companies were based, including the Studebaker car. e historical impact of these industries are well preserved in the iconic mansions owned by the compa nies higher ups. Colloquially referred to as “Studebaker Mansions,” these homes have been maintained and are now muse ums and bed and breakfasts.

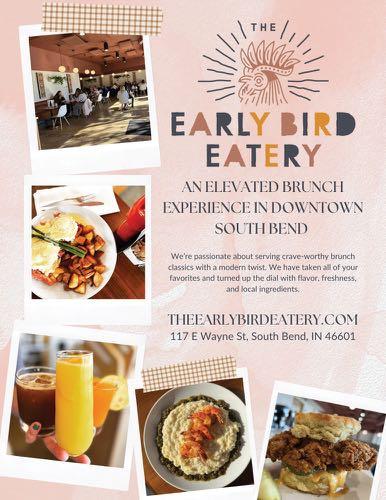

As we formed e Obsession, I knew I wanted South Bend to be an import ant piece of Issue 03. e excessiveness of Extravagance is dizzying — it’s the giddiness of becoming tipsy on cham pagne. Luxury is coursing through your bloodstream; it’s in the soft movements of your wrist as you sip and in the ow of your satin gown. Luxury is also linked to history and value that collects over time to be appreciated anew. We chose the Beiger Mansion as our shoot location to create this experience.

Beiger Mansion is steeped in history. It was completed in 1908 and has since been restored, after a disastrous re, and meticulously curated by Ron Montan don and Dennis Slade. e mansion is completely unique. Every wall is covered in framed portraits and ornate mir rors. e armoires and co ee tables are topped with vases over owing with oral arrangements. Curtains and pillows are accented with tassels and embroidery. Some honorable mentions include the life-size suit of armor, the grand marble replace and the cellarium. e space

balances antiquity with this subtle vi brance that feels contemporary. e main dining room feels like the set for So a Coppola’s Marie Antionette, designed for high tea and a dance party. To compli ment and contrast the scene, models wore modern renditions of Rococo era garments. e energy in the mansion was so alive as models swayed to Frank Sina tra being played over the sound system.

Issue 03 took the ideas of obsession and community and altered how we see our selves, taking Strike outside of the studio to places that now feel like home. While

we are not the rst or only students to begin this venture, it was important to Strike that we create a connection with our college town. We feel beyond grate ful to have been able to shoot at Beiger Mansion and bring a piece of local histo ry to the pages of this issue. e kindness extended to us by South Bend creatives like Mr. Montandon and Mr. Slade has helped begin to bridge this gap and grow our own Strike community.

By Gracie Simoncic

Chandeliers, crystal glasses. Bread and butter. Add some jam.

Co ee and cream. Sticks of honey. A teapot warms her soft hands.

White table cloths. Ebony chairs. Flowers weaved into her hair. Velvet couches. Golden candlesticks. Anoth er glass of wine.

e soft hymn of a violin.

Street lamps, crumpled cans. Empty cup boards. She shudders. Peeling walls. Narrow halls. Sawdust never

Down in the village, she, only a child, waits. In shoes without soles and rags for clothing. e clock ticks. e hours chime. A knock never comes. Plates are decorated with strawberry pastries. Bowls are lled with cream and berries. White hands grasp platters of goodies. One by one men in black and white lter into the dining room of golden mirrors and glistening chan deliers. Dessert is served and laughter is pervasive.

A ceiling leaks into a pot of brown liquid. Dust accumulates on wooden

swept away.

A twin bed. A frayed blanket. A uorescent bulb fades.

A cold oor. A kindling re. An empty tin of grain.

e muteness of dreams forgotten.

Stained walls and stained glass windows. Su ocating silence and loathsome laughter.

A man knocks on the door. A woman in a bonnet opens.

e clipboard that says ”support for the unfortunate” is given a shiny smile and a shake of the head.

A pleading face. A door closes. A man steps back. He walks away.

cupboards. A child’s life withers with a single uorescent bulb above her. Minute by minute the light grows softer, mo ment by moment the child grows quieter. Supper is missed and silence is deafening.

Silver spoons click against glass. Drops from the ceiling thump against iron. Seconds served, then thirds and fourths. First meals skipped, then seconds, then thirds. A glass is shattered and laughter erupts. A window is broken and shivers commence. Plates are cleared brimming with sweets untouched. A child is forgot ten, uncared for, unloved.

By Jane Miller

it’s the giddiness of becoming tipsy on champagne.

Beauty: Alexy Monsalve

Design: Anna Kulczycka and Kyla Goksoy

On-Set: Taylor Dellelce and Trinity Reilly

Photography: Grace Beutter and Olivia Guza

Production: Gracie Simoncic, Ida Addo, and Megha Alluri

Styling: Ebube Obi-Okoye, Emiliegh Yan, Gracie Simoncic, Maddie Sullivan, and Mary Kate Temple

Writing: Mae Brennan, Mary Clare Cameron, and Trinity Reilly Models: Claire Niehaus, Ian Coates, James Galante, Maddie Sullivan, and Maya Nyachae

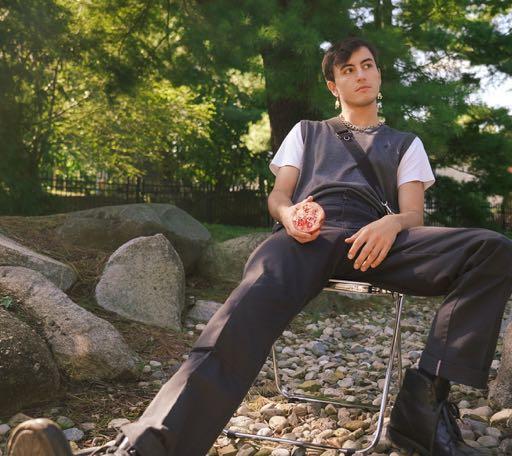

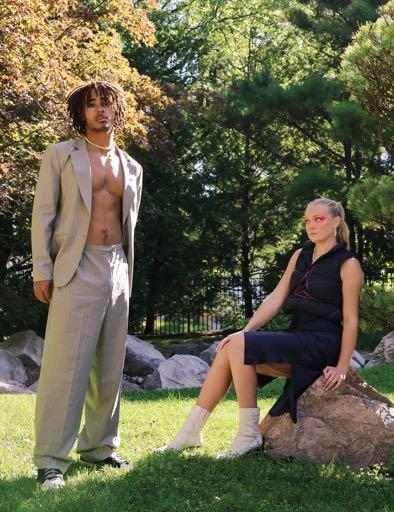

Beauty: Skye Sharp and So a Gomez

Design: Christina Sayut and Sydney Ellis

On-Set: Annelise Hanson, Mae Brennan, Taylor Dellelce, and Trinity Reilly

Photography: Leah Ingle and MK McGuirk

Production: Gracie Simoncic, Ida Addo, and Megha Alluri

Styling: Ebube Obi-Okoye, Emiliegh Yan, Gracie Simoncic, Maddie Sullivan, and Mary Kate Temple Writing: Helenna Xu and Katie Sharp

Models: Andy Donovan, Emileigh Yan, Skye Sharp, and Tor Cox

Beauty: Alexy Monsalve, Skye Sharp, and So a Gomez

Design: Christina Sayut and Devlin Hose

On-Set: Ryan Bland, Shannon Kelly, Taylor Dellelce, and Trinity Reilly

Photography: Leah Ingle, MK McGuirk, and Olivia Guza

Production: Gracie Simoncic, Ida Addo, and Megha Alluri

Styling: Ebube Obi-Okoye, Elle Akerman, Emiliegh Yan, Gracie Simoncic, Maddie Sullivan, and Mary Kate Temple

Writing: Connor Marrott, Isabelle Grassel, and Maddie Sullivan

Models: Annelise Hanson, Ashlyn Poppe, Audrey Wild, John Paul Llanos, Katie Compton, Kyla Goksoy, Matthew Guarnuccio, and Micaela Alvarado

Beauty: Alexy Monsalve

Design: Annie Brown and Devlin Hose

On-Set: Katelyn Wang, Ryan Bland, Taylor Dellelce, and Trinity Reilly

Photography: Grace Beutter, MK McGuirk, and Olivia Guza

Production: Gracie Simoncic, Ida Addo, and Megha Alluri

Styling: Ebube Obi-Okoye, Gracie Simoncic, Maddie Sullivan, and Mary Kate Temple

Writing: Cameron Oglesby, Gracie Simoncic, Jane Miller, and Maddie Arruebarrena

Models: Cleveland Sellers, Dami Bertin, Eno Nto, and Hope Gallagher