UNITED STATES EMBASSY BRASÍLIA

Inside

Roberto Burle Marx’s 1938 design for the rooftop garden of the Ministry of Education and Health (today known as the Gustavo Capanema Palace) in Rio de Janeiro

front cover:

front cover:

Inside

Roberto Burle Marx’s 1938 design for the rooftop garden of the Ministry of Education and Health (today known as the Gustavo Capanema Palace) in Rio de Janeiro

front cover:

front cover:

“An embassy is a symbol of the relationship between peoples and countries. Sixty years after the completion of the original chancery building, this new embassy building, built on the same location within the heart of Brasília, renews that commitment to our relationship. It honors our past accomplishments together while serving as a symbol to reinforce the shared ideals and goals of our nations. The new building also celebrates the history and unique aesthetic of the city of Brasília, while bringing a fresh perspective of what an embassy can be. I am particularly pleased with how the building will enhance and reflect the visual characteristics of Brasília while also representing inclusion, community, openness, and sustainability—values our two nations share.”

Douglas KoneffChargé d’Affaires Ad Interim

U.S. Embassy Brasília

November 2022

Map of Brazil, highlighting its major cities and waterways. The federal capital, Brasília, is the sole major city located near the center of the country.

When Brazil announced its independence in 1822, the United States was the first to recognize the new nation. Today, the countries enjoy a strong and growing partnership, anchored by the U.S. Embassy in Brasília and four consulates general across the country.

Positioned in the heart of Brazil’s federal capital, the embassy supports a rich and open dialogue on issues ranging from economic growth and prosperity to educational access, global health, and climate change. Sharing space with twelve U.S. federal departments and working with over 10,000 consular visitors annually, the embassy is an important part of the United States’ work across South America.

The 12-acre site is prominently located at the entrance to the Southern Embassy Sector, close to the ceremonial Monumental Axis that organizes Brasília. With its renowned modernist urban plan, architecture, and landscapes, the city—a UNESCO World Heritage site—provides an extraordinary cultural context in which to design a platform for strong relationships among people and governments.

In 2016, the U.S. Department of State Overseas Building Operations (OBO) commissioned architect Studio Gang and landscape architect OLIN to design a new embassy in Brasília that builds on the legacy of this remarkable place and expands on the deep foundations of Brazilian-U.S. diplomacy. With its bold structural expression, curving form, and open, welcoming gesture to the city beyond, the new campus design honors the daring modernist history of Brasília and its original designers. By bringing the latest in building innovation and a contemporary ecological perspective to the World Heritage city, it simultaneously aims to catalyze a more mutually beneficial future for the two nations, as well as the planet we all share.

The idea to transfer Brazil’s capital from coastal Rio de Janeiro to the country’s interior dates back as far as the 19th century. Conceived as a means to unify the diverse nation and grow its economy, the capital’s relocation began in earnest in 1956 under President Juscelino Kubitscheck, accompanied by a national competition that called on architects, engineers, and urbanists to plan the new city from scratch. The winning entry of Lúcio Costa (1902–1998) laid down Brasília’s foundational design gesture of two crossing axes, which resembles an airplane or bird in flight. Rising out of Brazil’s highlands in less than four years, Brasília was inaugurated in 1960—an impressive feat of planning, labor, and imagination.

The U.S. Embassy’s distinguished location, near the heart of Costa’s plan and major cultural and civic institutions, signified the close friendship between Brazil and the United States. Selected by Secretary of State John Foster Dulles in 1958 when Brasília was still heavily under construction, the site’s position also reflects the city’s functionalist design, which divides the capital into superblocks and sectors by use.

Above: Workers march through Brasília’s Cerrado grasslands as the National Congress Building rises behind them, ca. 1959.

Left: Brazilian President Juscelino Kubitschek (left) and planner Lúcio Costa (right) locate the Monumental Axis in 1957.

Above: Workers march through Brasília’s Cerrado grasslands as the National Congress Building rises behind them, ca. 1959.

Left: Brazilian President Juscelino Kubitschek (left) and planner Lúcio Costa (right) locate the Monumental Axis in 1957.

Left: The location of the U.S. Embassy, marked here by the Great Seal of the United States, is overlaid on Lúcio Costa’s 1957 competition-winning sketch of Brasília’s urban plan. Costa organized the city along “two axes crossing at right angles; the sign of the cross itself.” Integrated into the highlands, the cross adapts to the topography by curving along the natural ridge. View corridors along the axes highlight the city’s civic buildings.

Below: The people who built Brasília included thousands of migrant workers, as well as members of the nearby Quilombo Mesquita community —many of whom still live in the area surrounding Brasília. The city’s construction markedly changed the landscape they had farmed and maintained for centuries.

An aerial view of Brasília reveals the proximity of the United States Embassy to the city’s Monumental Axis and the landmark buildings that line it.

National Congress

In February 1960, shortly before the city’s inauguration, Presidents Dwight D. Eisenhower and Juscelino Kubitschek laid the chancery’s cornerstone together, reaffirming the nations’ friendship and their shared goals.

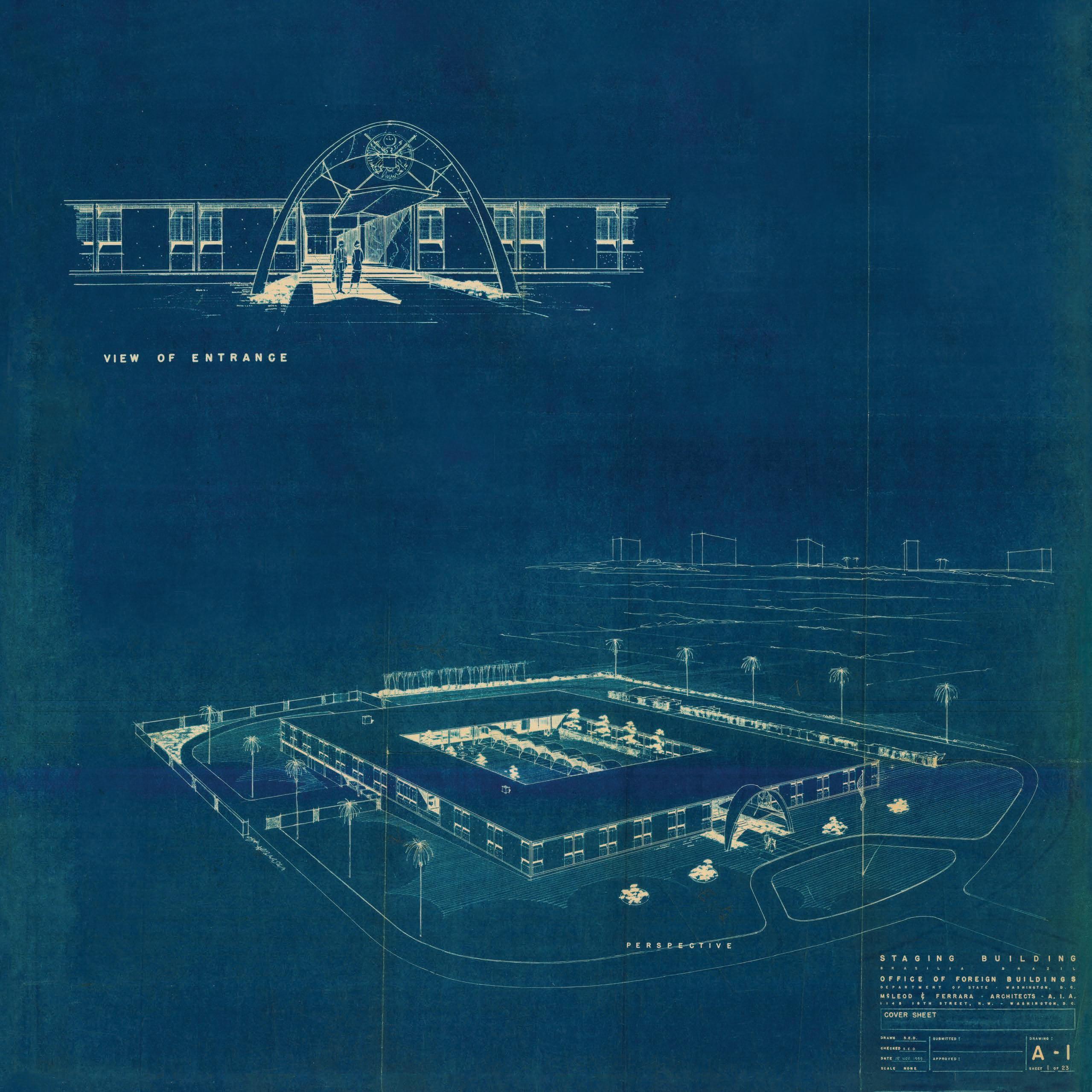

Designed by Washington, D.C.-based firm McLeod and Ferrera and inaugurated in April 1962, the first chancery was a modest, single-story building that reflected the post-World War II ethos of the Office of Foreign Buildings. Clad in white brick and stucco, and organized around a central courtyard, the architecture was modernist, planar, and animated by the gardens and waterscapes of Brazilian landscape designer Roberto Burle Marx. The Ambassador’s residence and housing for embassy staff occupied most of the new building, with the front bar set aside for offices.

The chancery was expanded in 1972 with a two-story addition designed by Omaha-based architecture and engineering firm Henningson, Durham, and Richardson (HDR). The new structure, clad in white Vermont marble, added a courtyard surrounded by office space immediately to the southeast of the original chancery, continuing its simple, modern lines with a formal representational approach and distinct entrances for staff and visitors.

Aerial photograph of the original chancery, ca. 1960s. In the decades since, the surrounding land has filled with embassies and Brazilian departmental offices.

Blueprint perspective drawings of the original 1962 United States Embassy in Brasília, designed by McLeod and Ferrera. The arched main entrance shown in the drawings was never built.

The 1972 addition brought improved functionality to the mission. Like the original chancery it abuts, the new building was rectilinear, with a courtyard garden cut into its floorplate. Its car park and main entrance featured shade trees and soft curves.

The embassy’s diplomatic presence and main entrance have faced east since 1962. Over time, other nations constructed their chanceries facing west, which left the U.S. chancery’s back to its neighbors. A top goal for the renewed campus is to create stronger relationships with these neighbors, as well as more fluid circulation paths for the different users across the embassy site.

The coffered ceiling of the 1972 lobby, with the new courtyard garden beyond.

The coffered ceiling of the 1972 lobby, with the new courtyard garden beyond.

A photograph of the original chancery courtyard. While many of the garden’s plant species and landscape features specified by Burle Marx in 1960 were substituted in the following years, the angular pools, rock arrangements, and tropical scheme that remained maintained the spirit of his plan.

Brazilian landscape designer Roberto Burle Marx (1909–1994) was renowned for his expressive, geometric designs and tropical planting schemes. As a self-taught botanist and trained artist who was captivated by Europe’s expressionist painters, Burle Marx infused his gardens with lyricism, drama, and experimentation. His desire to celebrate and preserve Brazilian landscapes added an ecological purpose to his work.

Among the array of tropical species Burle Marx selected for the 1962 chancery courtyard garden were red- and purple-flowering plants and large pequi fruit trees. A diverse range of aquatic vegetation also formed part of his original plan, complementing the angular pools and visually linking together to create a sense of continuity in the small space. A scalloped canopy walkway designed by McLeod and Ferrera crosses the courtyard, providing shade and echoing the curved, modernist forms present throughout Brasília. The color, rhythm, and cohesion that defined this small garden and many other Burle Marx landscapes underscores the cheerfulness of the age and its confidence in the future.

Top: The courtyard garden by Roberto Burle Marx in the original chancery, shown here in the 1970s.

Bottom: Roberto Burle Marx wearing elephant ear leaves during a botanical expedition in Ecuador, 1974.

1.

2.

1.

2.

Concrete’s ability to make curving and tapering forms possible—from the repetitive arched façade of Oscar Niemeyer’s Alvorada Palace to his crown-like Cathedral—is on exuberant display in Brasília and Brazil at large.

Responsiveness to the sun is the most apparent environmental driver of the local architecture, where various types of screens, louvers, and brise-soleils are deployed to mediate the intense daylight during the long summer season. The play of light and shadow across these often curved and layered façades brings additional interest to their forms. Landscape elements such as plants, water, and topography also permeate the city, bringing richness and cooler microclimates to its outdoor gathering places.

Studying this vocabulary informed the design of the new embassy, allowing its architecture to benefit both functionally and aesthetically from the innovations of Brazil’s earlier generation of architects.

6.

4.

3.

(1) A model of the Cathedral of Brasília, 1958.

(2, 3) Alvorada Palace, Brasília, 1959.

(4) Niemeyer’s Edifício Copan, São Paulo, 1961.

(5) Chapel of the Alvorada Palace, Brasília, 1959.

6.

4.

3.

(1) A model of the Cathedral of Brasília, 1958.

(2, 3) Alvorada Palace, Brasília, 1959.

(4) Niemeyer’s Edifício Copan, São Paulo, 1961.

(5) Chapel of the Alvorada Palace, Brasília, 1959.

The new embassy design anticipates a greener, more vibrant and equitable future for the United States’ diplomatic mission in Brazil. Conveying an overall sense of optimism and vitality, the project draws on the unique qualities of Brasília’s natural and built environment—from the prevalence of indooroutdoor spaces to the innovative use of reinforced concrete— to honor this heritage while evolving it to address the needs of the twenty-first century and beyond.

The design aims to deepen connections between people and place, creating opportunities for cultural exchange and community-building at all scales. The landscape honors the tropical exuberance and richness of Burle Marx’s vision, while weaving the region’s indigenous Cerrado ecosystem into daily encounters, providing visitors, staff, and diplomats with an ever-changing experience of Brazil’s biodiversity and beauty.

Through its honest use of material, the embassy’s elegant and high-performance façade builds on Brazil’s long history of material and construction innovation, such as climate-responsive architecture and finely crafted mosaics. Environmental stewardship and resilience are further strengthened through incorporating renewable energy and other green strategies into the embassy facilities and site.

Officials and diplomatic visitors approach the embassy from the northeast, along the representational path, which echoes the curve of the new chancery building as it passes through the site’s biodiverse landscape.

The original embassy, with its rectilinear form and central courtyards, was designed for elegant efficiency and indoor/outdoor use, according to the modernist principles of the time. The new embassy carries these concepts forward and expands on them, reaching beyond the modernist box to engage the entire site and its urban and ecological context in support of the diplomatic mission.

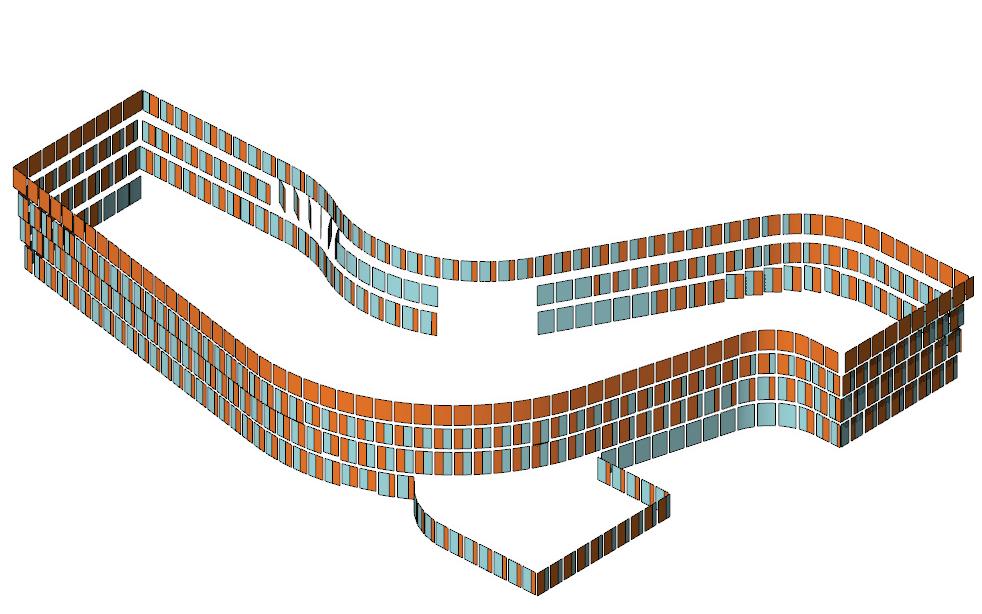

To unify and clarify the embassy’s complex functions while creating a memorable experience, the design deploys a formal tool prevalent in nature: curvature. Seen throughout Brasília, from the monumental civic structures of Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer (1907–2012) to the sinuous shoreline of Lake Paranoá, curves at the new embassy exercise their full capacity to foster a flow of relationships. Each one is leveraged to generate intimacy, connection, or a feeling of welcome.

The architecture and landscape design are guided by a series of arcs of different radii that blend seamlessly and organize the different paths of movement across the site. Situated at its highest point, the new chancery greets visitors arriving from all approaches with a dynamic identity and sense of invitation. Its curved plan gives the façade a sense of movement, animating the journey of officials and diplomats along the representational path and verdant garden swath. This path leads to the main entrance—located at the nexus of the urban view corridors linking Brasília’s Residential Sector, Monumental Axis, and Congress— where the building bends inward to embrace visitors as they arrive. Embassy staff and consular visitors approach the building from the east, intuitively guided by garden pathways through an unfolding sequence of spaces.

The chancery bends in and out like a river. Its coves and promontories form generous openings, offer views of civic and cultural landmarks, and merge effortlessly with the landscape. Expanding on the oasis quality of the restored Burle Marx garden at the northwest, the architecture and landscape work together to create a range of courtyards and gardens across the site. Making the joy and health benefits of Brazilian indoor/outdoor living readily available, these green spaces infuse the entire campus with a simultaneous sense of openness and protection, and interweave the natural beauty of the city and region into the everyday.

Architecture and landscape fluidly merge in the design, as shown in this rendered site plan.

Diplomacy is, by definition, the art of building and maintaining constructive relationships. The design of the new embassy aims to embody and facilitate communication by setting up multiple ways for people to connect with each other, as well as Brasília’s pleasant climate, rich ecology, and extraordinary architecture.

At the scale of the individual, the embassy’s flexible, day-lit meeting and working spaces support productive interactions and connection to the outdoors, encouraging planned and impromptu collaboration. At the scale of the site, a range of indoor-outdoor spaces enable gathering to promote intellectual and cultural exchange between diplomats, staff, and visitors. At the city scale, a visually open and welcoming perimeter establishes a gracious relationship between the site and its surroundings while maintaining access, safety, and security. At the scale of the nation, the embassy serves as a vital symbol of the relationship between the United States and Brazil, while its sustainable design demonstrates a greener way forward for diplomatic architecture at the global scale.

Sustainably sourced wood brings a warm, natural feeling to the interior of the gallery and the spaces that branch off from this hub.

The representational path continues into the chancery, through the main lobby, and into the gallery, which is located directly in the center of the building. This daylit, triple-height space is the hub for the entire embassy. Organizing the flow between work, meeting, and dining spaces, it also establishes a natural social center where people can cross paths and converse. A grand stair connects to a spacious balcony that overlooks the space below, and provides views out to the terrace and landscape beyond.

An early model reveals the gallery’s fluid connection between outdoors and indoors, as well as the architecture’s use of horizontal planes to permit views while ameliorating solar heat gain.

A section cut through the gallery shows how the space links multiple levels and brings diffuse natural light and living vegetation deep into the interior.

The legacy of indoor-outdoor spaces in Brasília is carried forward in the new gallery. Daylight filters in through its glazed entry, skylights, and façade, while staff and visitors gain clear views and easy connections to the garden, terrace, and the consular spaces below. An intricate ceramic tile mosaic on the eastern wall brings color and a human scale to the space.

The chancery’s slender footprint provides abundant natural light and outdoor views for the workspaces, contributing to the health and well-being of the embassy community.

The workspaces are developed on an activity-based model to establish spaces for community and connection, as well as spaces for tasks requiring focus. The modular interior planning approach allows for movement and energy to be apportioned according to the mission’s evolving needs, optimizing flexibility to accommodate growth and change over the building’s lifecycle.

In the executive suite, a shared entrance foyer acts as a connection point for staff and visitors, encouraging openness, connection, and transparency. Full of daylight and warm wood tones, the Chief of Mission’s office provides a comfortable environment for work and conversation.

Locally sourced emerald marble brings the geology and beauty of the region to the space.

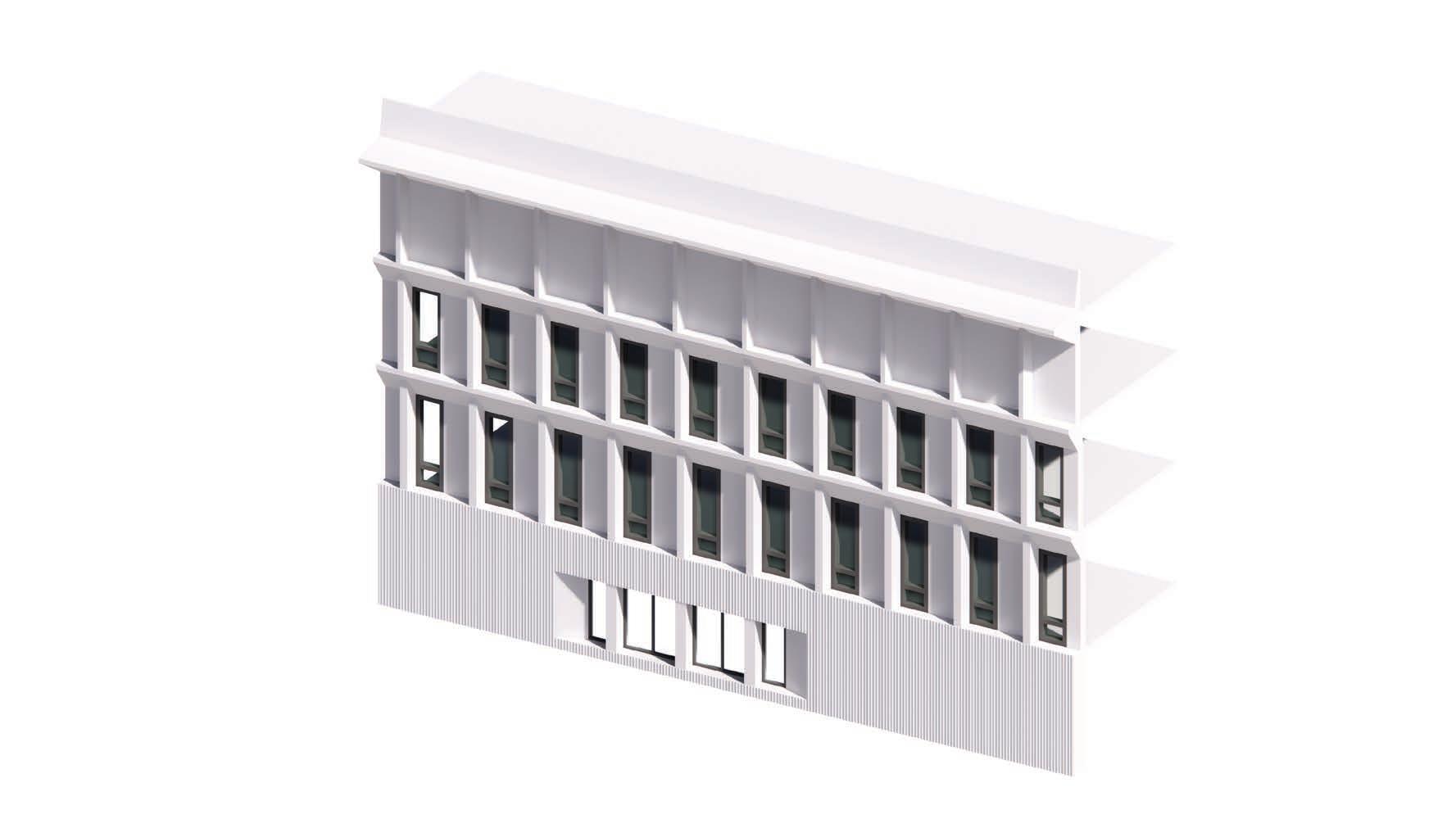

As fluid and organic as the new chancery may appear, it is composed of regular modules and devised for efficient construction. The geometry is built up from straight segments and arcs, and driven by the desire to create an intuitively functional and spatially compelling experience for all of the embassy’s diverse users.

Two overlapping circles establish the layout of both the architecture and landscape. The larger of the two circles encloses the bustling center of the chancery, with the gallery located within. The smaller of the two marks out the midpoint of the building, gently pushing it inward to form the curve of the main entrance. This geometry draws people from the surrounding site into the main lobby and gallery, creating a strong sense of invitation and simplifying movement across the site.

Reaching beyond the center and extending to form an S-shape, the chancery’s spine organizes its different programs into two wings that provide a clear distinction of uses. Along the perimeter, the modular logic of bays accommodates the embassy’s operational needs and optimizes office floorspace, providing flexibility and adaptability for present and future uses. When viewed in perspective, the bays’ regular rhythm is perceptible and accentuated by the architecture’s curving walls and deep façade.

Above: A conceptual sketch by Jeanne Gang shows the elemental geometry that gives order to the chancery’s form. The building’s central axis is oriented toward the Monumental Axis of Brasília, connecting the embassy with the city at the urban scale.

The curves of the chancery are reflected in the landscape of the consular garden and the sheltering overhang of the consular entrance pavilion. The garden’s blend of native Cerrado grasses and other plants greets visitors with a sample of the biome’s diversity.

The consular services area is designed to accommodate a large volume of visitors with an inviting, intuitive, and calm experience. Natural light and materials create a warm welcome, while the soft curve of the space—echoed in the lines of the ceiling and the layout of the consular service booths—helps guide visitors while providing privacy at the booths. Views of the surrounding gardens contribute to a peaceful, open feeling for this important touch point between the mission and U.S., Brazilian, and third-country visitors.

Brightening the consular services area, a reception desk of mosaic tile continues the abstracted rainforest pattern featured in the gallery one level above.

Whether painted, printed, or woven into tapestries, the vibrant, densely layered compositions of Beatriz Milhazes combine Brazilian elements with American and European abstraction. Her references range widely from Brazil’s biodiverse flora and the Tropicália movement of the late 1960s, to Baroque architecture’s opulent and expressive forms.

Milhazes’ tapestry in the main lobby will bring texture and vivid color to the space, greeting visitors with a distinctly Brazilian sense of welcome. The tapestry will be woven in the centuries-old “basselisse” technique by Maison PINTON, master Aubusson tapestry makers.

The U.S. Department of State’s long-running Art in Embassies program celebrates the work of U.S. and host country artists, encouraging cross-cultural dialogue and fostering mutual understanding.

The work of two internationally renowned Brazilian contemporary artists will be on display in the new embassy. In the main lobby, a unique tapestry by Rio de Janeiro-based Beatriz Milhazes will greet those arriving to the chancery with her signature vivid colors and abstract geometry. Proceeding into the triple-height gallery space, occupants and visitors will find a suspended sculpture by Ernesto Neto, also from Rio, whose biomorphic forms evoke a sense of lightness and wonder.

Ernesto Neto’s art explores Brazilian traditions and ideas about the relationship between our bodies and the world around us. Often inhabitable or interactive, his pieces invite viewers to touch and sometimes smell them, offering a multi-sensory experience that encourages happiness and contemplation.

Shown above is Neto’s 2018 work Gaia Mother Tree, a sculpture made of hand-knotted cotton strips that was temporarily installed in the main train station of Zurich, Switzerland. Neto’s original sculpture for the new embassy’s gallery will similarly emphasize the grand height of the space, as well as its intended use as a central gathering place.

Delicate cobogó brick screens frame views of the surrounding gardens, filtering light while creating a sense of intimacy for those within.

A range of shaded courtyards and gardens throughout the embassy grounds welcome staff and visitors and provide space for conversation, events, and exchange. At the eastern edge of the restored Burle Marx garden, a pair of outdoor kitchens in the new courtyard pavilion provide a special gathering point. Here, the embassy community can meet, strengthen friendships, and celebrate holidays like the Fourth of July and Proclamação da República

As shown in this conceptual sketch by Jeanne Gang, the different ribbons of landscape interweave with the embassy buildings. The landscape works with the architecture to perform multiple functions, creating habitat for wildlife, storing and filtering water, providing shade and cooling, and promoting the health and wellness of embassy staff.

Fitness and exercise programming cluster around the restored Burle Marx courtyard in the northwest of the site. A fitness center lines the southern edge of the courtyard and its pavilion, with sport courts located to the north. Taken together, these programs make the Burle Marx garden a central node within the embassy site, reactivating the garden’s historic role as a social hub.

The fitness center is directly adjacent to an outdoor court, allowing fitness activities to seamlessly flow between inside and outside.

Complementing the campus’ ground-level courtyard gardens, the embassy’s terrace is an elevated perch with views of the surrounding landscape. Accessed directly from the gallery, this large outdoor social and event space provides a natural link between the indoor and outdoor spaces, serving as a relaxing forum to deepen relationships between staff and diplomatic visitors.

On a day-to-day basis, the terrace offers a lush, shaded environment to enjoy dining or meeting with colleagues. Surrounded by varying heights of vegetation, and framed by the sinuous chancery façade, the terrace creates an immersive environment for many types of embassy functions.

The terrace’s tropical plant species establish an abundance of colors and textures throughout the seasons, as well as visual privacy from the adjoining gallery, consular garden, and consular entrance pavilion. Staff and visitors can also take in views of the mature treetops of the neighboring French embassy gardens, located to the south.

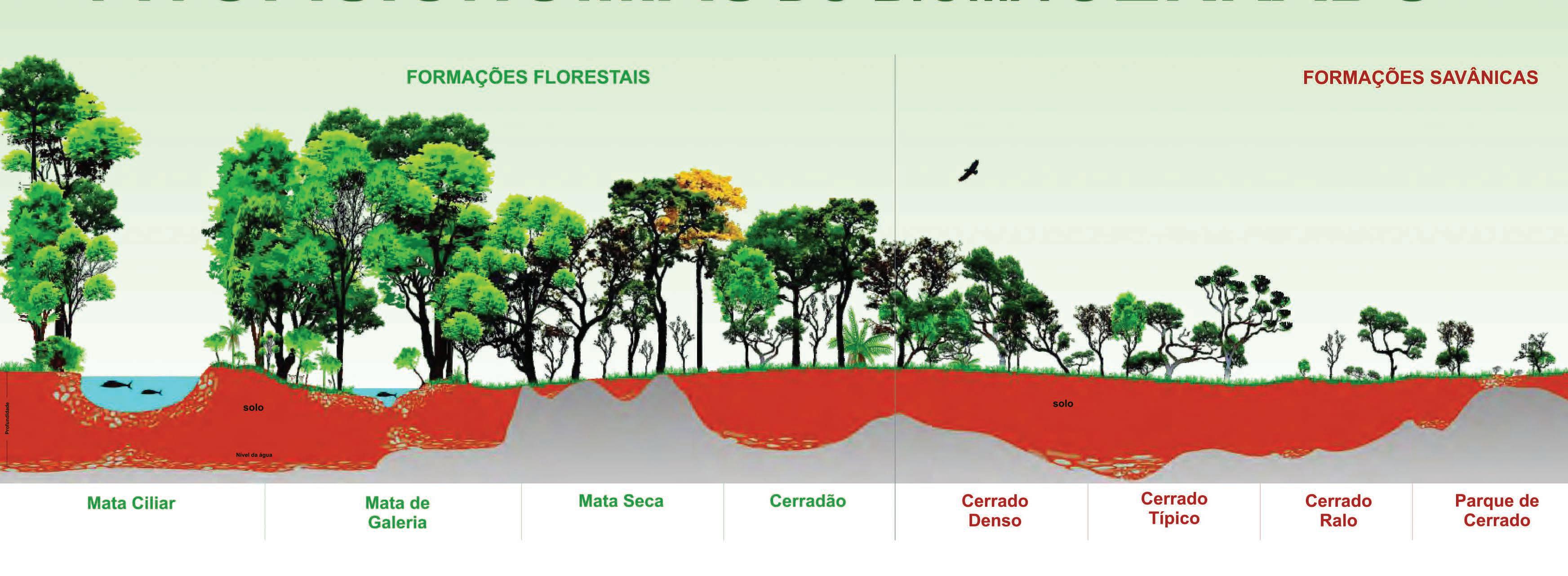

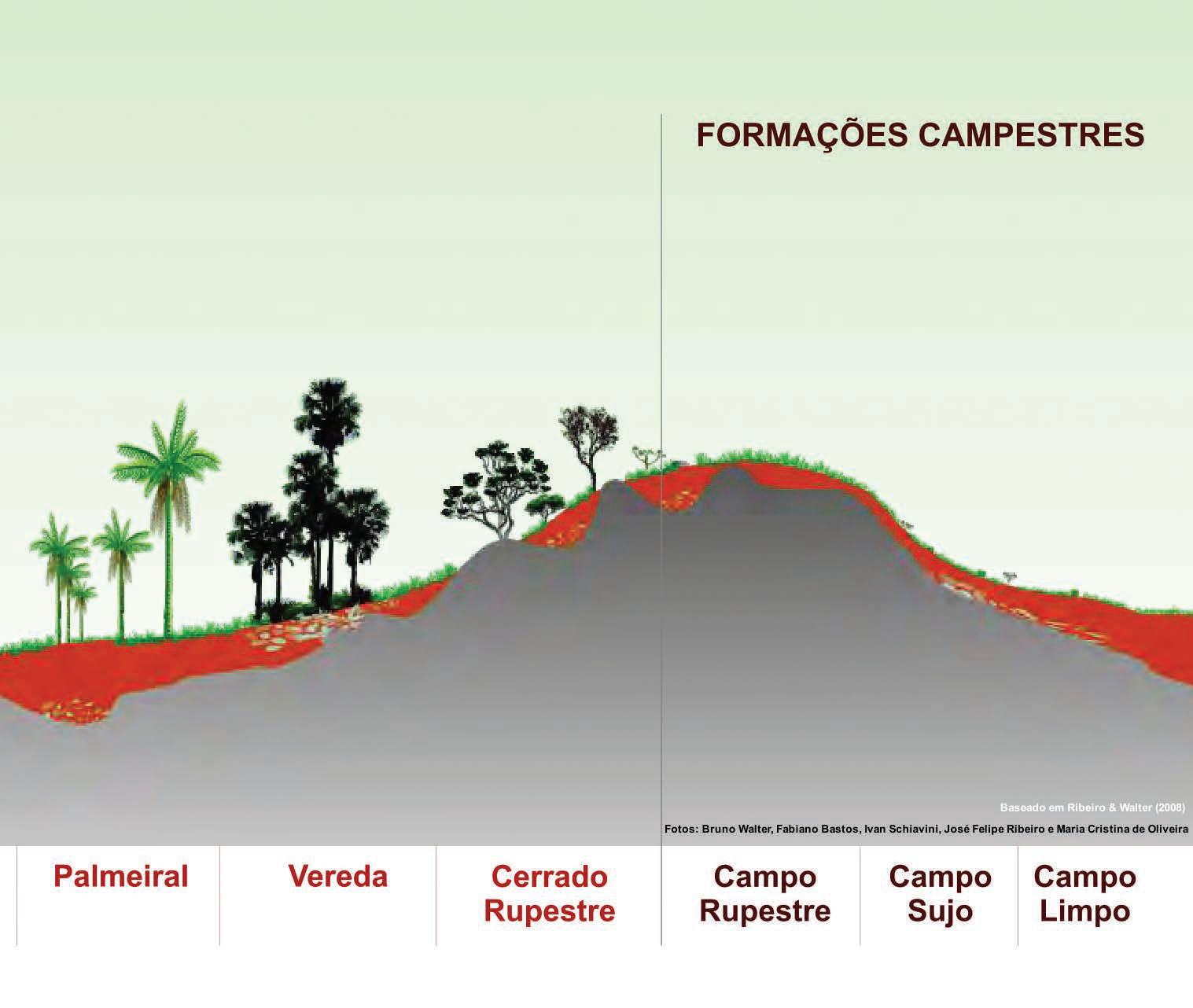

Known almost singularly for its iconic tropical Amazon Rainforest, Brazil is, in fact, home to five different biomes. Brasília is located within one of its most biodiverse, if most unfamiliar: the Cerrado, which covers approximately 22 percent of the country and supports approximately 4,800 endemic plant and vertebrate species, from golden grass (Syngonanthus nitens) to the maned wolf (Chrysocyon brachyurus).

The Cerrado’s visual richness stems in part from its seasonal variation. Vibrant, colorful flowering plants take on goldenbrown tones when they go to seed in summer. Gnarled, twisted, and bowed tree trunks with thick bark record the alternating abundance and scarcity of water during its two well-defined seasons: wet and dry. Today, the Cerrado’s ecological diversity, as well as its vulnerability to deforestation, is shifting public understanding of its importance.

The new embassy campus will be one of Brasília’s first civic projects to reintroduce this indigenous landscape. Seeking to join local partners in deepening appreciation for the Cerrado and the urgency of conserving it, the landscape design’s fluid mosaic of gardens, terraces, pathways, and vegetated roofs together magnify the subtle beauty of the biome and reinforce that Brasília lies at the heart of the Cerrado.

The landscape design of the new embassy highlights the golds, reds, and purples that characterize the vast Cerrado ecoregion.

Brasília’s annual rainfall is average for Brazil as a whole, due largely to its two seasons that flip from wet to dry.

Heavy rains during Brasília’s summer season regularly lead to issues of flash flooding, while low humidity during the dry season often results in droughts. As climate disruption, deforestation, and urbanization increase, these dualistic conditions grow even more extreme, raising the stakes of climate mitigation— whether at the scale of the embassy or the planet. Preserving and restoring Cerrado species, which store enormous amounts of carbon and act as giant sponges during the wet season, offers opportunities to combat climate change while protecting the region’s biodiversity.

Right: Many locales have four seasons, but Brasília has only two: wet and dry. Heavy rains between October and March comprise the wet season, while very low humidity dominates the remaining months of the year, which make up the dry season. Brasília also enjoys a consistently pleasant, warm climate year-round, with monthly average temperatures between 66°F and 72°F.

Below: The Cerrado landscape ranges from dense gallery forest along rivers to open grassland and shrubs at higher altitudes. The main type of vegetation within the biome, cerrado sensu stricto, is savanna woodland with 10 to 60 percent tree cover.

“The Cerrado is home to the most spectacular transformations that nature can provide. After a six months’ drought, when most of the plants are leafless and the only colors are the ocher of the soil, the thorn and limbs of the trees, with the full fall the Cerrado comes through.”

Roberto Burle Marx Brazilian Landscape DesignerRanging from lush, tropical vegetation to droughttolerant species local to Brazil’s savanna, three distinct planting zones—the garden swath, Cerradão, and Cerrado—organize the embassy’s landscape design.

Forming the heart of the landscape, the garden swath is a wishbone-shaped, richly planted series of gardens. It connects the restored Burle Marx garden in the west to the representational path and garden, and continues through the chancery’s main entrance, into the gallery, and back out to the terrace. Like Brasília itself, the garden swath is carved out of the Cerrado. Weaving together outdoors and indoors, and maintaining continuous views of the landscape, the zone is defined by dark green and silver tropical plants—a familiar planting system that features so vividly in the popular imagination of Brazil, and offers shade, comfort, and vibrancy.

Serving as a transitional layer of vegetation between the garden swath and the Cerrado planting zones, the Cerradão mixes drought-tolerant canopy trees and understory vegetation native to the region. Framing the garden swath at the center of the landscape, the Cerradão provides year-round greenery alongside seasonal variety.

The embassy’s largest planting zone, the Cerrado, enlivens and stitches together the remaining landscaped areas, from the American Center Garden and main entrance pavilion at the east to the fitness area at the northwest and the site periphery. Endemic grasses and herbaceous vegetation native to the biome burst with color in the wet season, and transition to layers of golds, bronzes, and yellows in the dry season.

The character of the embassy’s Cerrado landscape changes throughout the year. During the wet season, various tones of green, accentuated by colorful flowers, dominate the landscape. As the dry season arrives, the vegetation transitions to tones of gold and tan, highlighted by dark brown seed heads and pods, and residual stems.

The dancing forms and contrasting colors of the new landscape are underpinned by ecological principles, microclimates of topography, and solar orientation. Plant species are selected for their innate ability to balance the extreme changes in precipitation that take place in Brasília throughout the year. Less trafficked areas of the landscape comprise drought tolerant Cerrado vegetation that yield a burnished backdrop of gold and russet tones against the more lush, irrigated, and activated center. Embracing these contrasts showcases a commitment to resiliency and habitat restoration, advancing the embassy’s ecodiplomacy goals of environmental stewardship, while simultaneously celebrating the Cerrado’s visual richness.

In concert with establishing an intricate and inspiring native palette, melded with the equally culturally significant tropical palette, the planting design provides opportunities to educate embassy users and the greater public about the ecological history of the region and demonstrate precedents for future sustainable planting practices.

The embassy’s original courtyard garden, planned by Roberto Burle Marx, is an important piece of Brazilian design history that, over time, has shifted away from his vision. Using his 1960 drawings, the garden will be restored to fully reflect Burle Marx’s concept, bringing back the original planting scheme, rock sculptures, and water feature geometry. This renewed landscape will become the anchor for the northwest portion of the embassy site. To maintain its intimate courtyard character while updating the adjacent uses, the massing of the surrounding buildings remains the same, but the structures are replaced and reprogrammed as an outdoor pavilion, fitness area, and residences.

The restored 1962 courtyard hosts new uses along its porous perimeter. Cobogó brick screens allow natural light and views to filter through while maintaining the garden’s original, semi-enclosed character.

Located just fifteen degrees south of the equator, Brasília receives strong, direct light year-round—especially from the north—due to the steep angle of the sun. Providing shade and ventilation is therefore essential to creating comfortable indoor and outdoor spaces. Architects and builders have long managed the local climate using a variety of passive cooling strategies, from the pilotis and brise-soleils of Brazil’s modernists, to overhanging roofs and the Portuguese tradition of ceramic tiles (azulejos) that line façades and courtyards to reflect the sun and improve thermal comfort.

The new chancery’s façade design advances these inherited techniques using contemporary analytical tools and building technologies for site-specific outcomes that respond to the local climate. Not only providing shading, insulation, and skin that offers protection from the weather, the façade is also structural, and precisely tuned to maximize environmental performance as well as programmatic and security requirements.

The American Center Garden, framed by the gentle curves of the consular services lobby and office levels above, offers a lush, shaded area for cultural and educational events. The soft green edge of the elevated terrace blends with the vegetation of the intimate courtyard below, creating a multi-layered garden experience.

The design of the chancery façade takes Brazil’s tradition of layered, screen-like façades even further into the third dimension. While projects like Niemeyer’s Obra do Berço, shown at right, operate in the vertical plane by stacking fins in front of glazing, the chancery façade engages both the vertical and horizontal planes—not only using them to block and direct sunlight, but also deepening and “pulling apart” these layers to create occupiable, sheltered spaces at the threshold between indoors and outdoors.

This condition is readily visible at the south end of the gallery, where the façade’s grid projects outward and away from the transparent curtainwall, becoming a balcony and a trellis for hanging plants that overlook the outdoor terrace below.

Right: The gallery’s large skylight filters natural light onto the balconies and dining area below, visually connecting indoors and outdoors in the vertical dimension.

Above: Obra do Berço, in Rio de Janeiro, was designed by Oscar Niemeyer and completed in 1937.

The depth and angle of the chancery’s structural concrete fins respond to specific solar conditions— both self-shading to reduce solar heat gain and maximizing useful natural daylight to the floorplates. Given Brasília’s southern tropical latitude, the fins are most pronounced on the north, east, and west where solar gain is highest and the most shading is needed. On the south face, there is less solar exposure, and accordingly the fins’ depth is shallower.

In addition to the fin geometry, the infill of each façade bay is precisely tuned to a mix of factors. As the façade uncoils in plan, areas that locally receive less solar gain are granted more glazing; conversely, the more exposed bays have narrower windows.

The infill of the bays also responds to program. Bays that are adjacent to public-facing programs or work areas that need daylight are more open than areas that need less or no daylight, such as some meeting rooms, mechanical spaces, and storage.

Below: The infill of each façade bay began with a careful analysis of three interrelated factors: solar exposure, adjacent program, and opportunity for visual connectivity. Weighing all three together, a percentage of opaque wall versus window was then assigned to each individual bay. The result is five types of infill panels, ranging from fully opaque to full glazed and arranged in increasing increments—like a horizontal shutter being drawn across each bay— that integrate the competing demands into an orderly composition.

Above: Designed in plan, section, and elevation, the façade’s north and south overhangs were carefully tuned to the sun angles of Brasília’s winter and summer solstices, respectively. Around the time of the summer solstice, the sun’s path “tips over” directly overhead to shine on the building’s southern façade. The slight overhang on this face accounts for the sun’s maximum angle of 82 degrees altitude from the southern horizon.

Left: Built by local craftsmen with deep knowledge of concrete construction in Brasília, a full-scale mock-up of the embassy’s northwest corner demonstrates the design’s integration of structural, environmental, and aesthetic criteria. The façade’s selfshading properties are evident in the long shadow line stretching down the side of the corner fin.

In addition to the use of concrete as a structural and finish material, Brazilian architecture also frequently employs indigenous woods, intricate screens, and ceramic tiles—materials that help cool hot temperatures, let in light, and make use of local resources. The new embassy incorporates all of these fine-grained elements, imbuing the project with a sense of craft and place as well as playfulness and beauty.

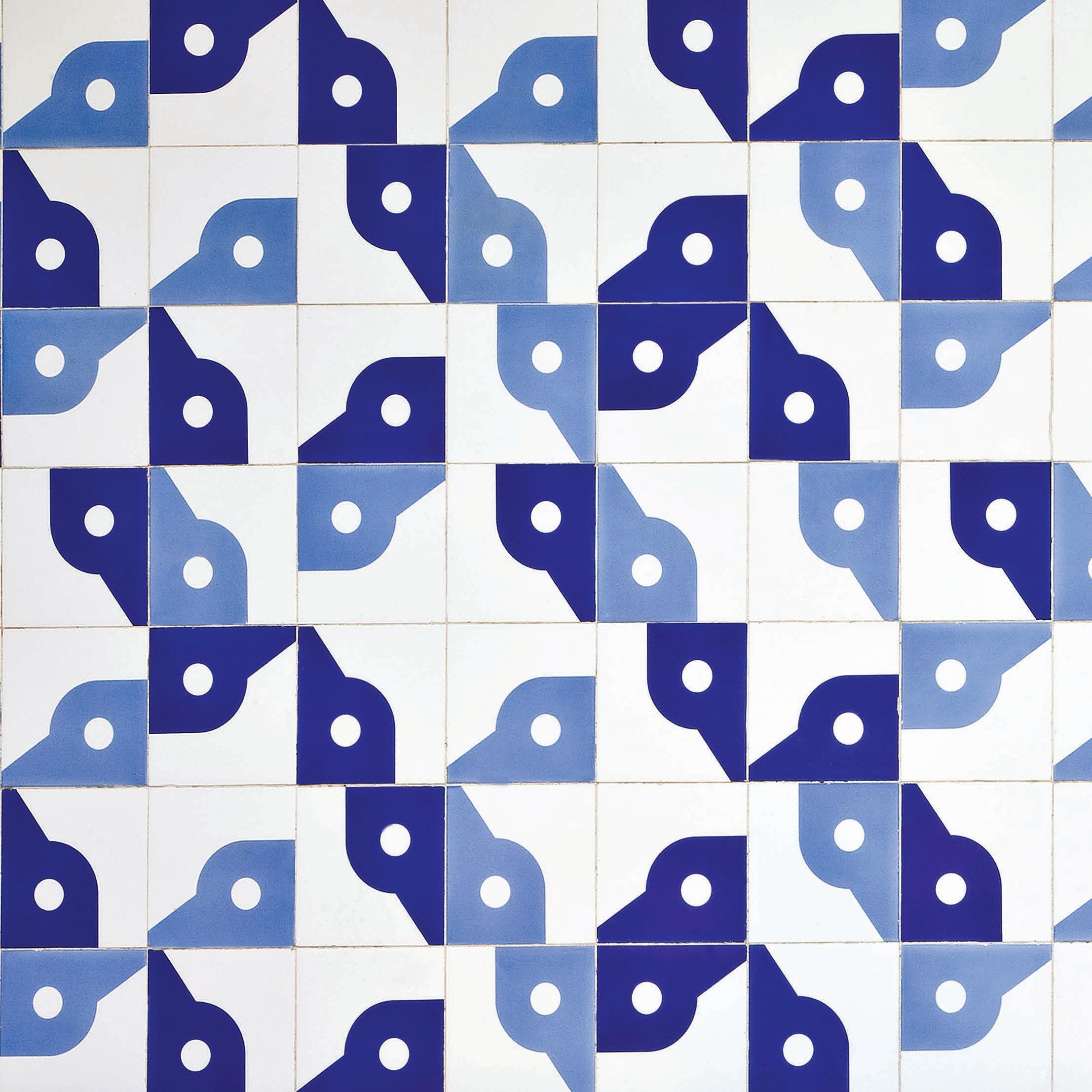

The distinctive work and process of Athos Bulcão (1918–2008) was an important touchstone for the design. Bulcão, who is most often remembered for the vibrant color and bold patterns of his screens and ceramic mosaics, created his work in very close collaboration with artisans. His characteristic patterns emerged in conversation with masons as they stood together on construction sites, turning, flipping, and laying each tile on the wet cement mortar bed to find beautiful, lively compositions in that moment.

The new embassy design builds on this history of using simple, local materials to make a bold visual impact. Hand-sized ceramic tiles bring a sense of familiarity, texture, and human scale to prominent interior and exterior spaces throughout the site, including the gallery and façade bays.

Opposite, top: The gallery features a multi-story ceramic tile mosaic that abstracts the distinctive leaves of Brazil’s tropical plants through a contemporary version of Bulcão’s process.

Above: Brazilian painter and sculptor Athos Bulcão’s tile- and screen-work are part of Brazil’s living tradition of geometric, graphic play. Here, he works with masons on site to define the layout of a mosaic.

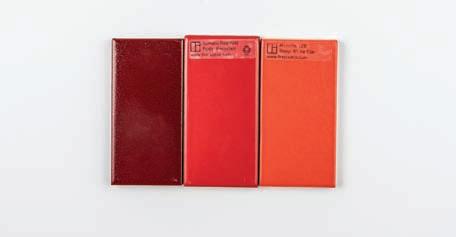

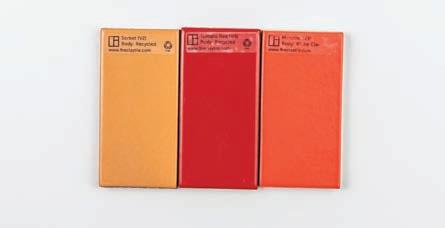

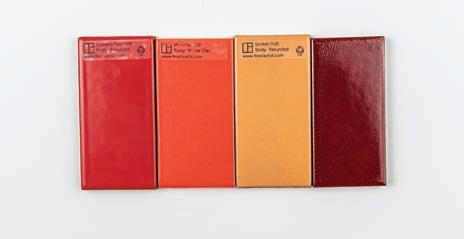

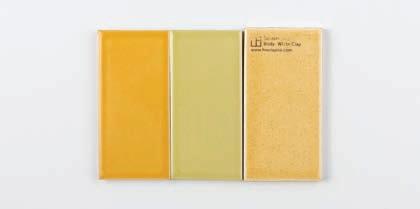

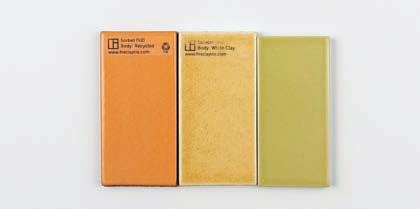

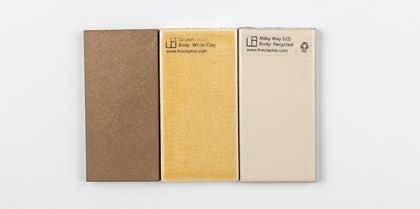

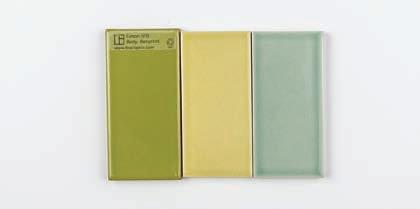

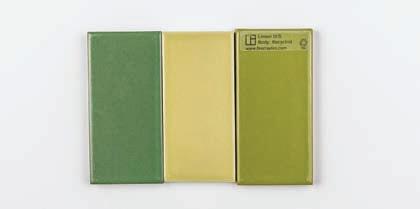

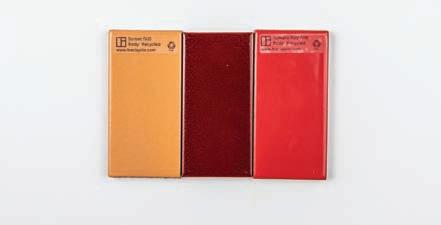

Specific plants from the Cerrado were used to define the façade’s tile palette. Savanna grasses and low-slung plants that typify the ecosystem’s wet and dry seasons were referenced to determine the neutral base colors, while the accents draw inspiration from the warm and cool tones of indigenous flowering plants. In both cases, key landscape species were identified and emulated with combinations of three or four tile colors. Arranged in vertical bands on the curving façade, the tile creates a shifting mural in tune with the landscape.

Warm Accents

Cool Accents

Wet

Wet

Like the bright, multicolored work of Athos Bulcão, ceramic tiles introduce a sense of color, contrast, and geometric play to the embassy’s façade. Two color groups organize the tile palette—a set of neutral bases and bright accents, which evoke the ocher carpet of the Cerrado landscape and its vivid pops of color. For the neutral bases, the design adopts the greens and golds characteristic of the landscape’s wet and dry seasons. For the colorful pops, it draws on the rush of reds, burgundies, oranges, blues, and violets seen in the Cerrado’s spring blooms.

Applied in vertical bands, the colored tiles are selectively placed to harmonize with the site’s ribbons of vegetation. Where the drier Cerrado ribbon sweeps toward the façade, the base layer responds with an abundance of gold hues. Where the verdant garden swath passes through the gallery to the terrace, green tones appear. The accents also move across the building in response to the local presence of different species of flowering plants. The resulting expression is both playful and principled, tying the embassy to its environment.

The principles of ecodiplomacy guide the embassy’s sustainability goals. Defined as the act of conducting foreign relations by demonstrating a commitment to the environment, ecodiplomacy depends on both policy and practice.

To ensure the embassy treads lightly on the local site and the planet as a whole, the design thoughtfully incorporates green strategies and systems into the DNA of the project.

From the reuse of the existing Burle Marx courtyard, which informed the broader landscape strategy of promoting the local habitat and hydrology, to the strong emphasis on conservation, efficiency, daylight, and views, the design improves the building’s environmental footprint. It simultaneously supports the well-being of all occupants, creating a healthy and pleasant place for diplomacy that can lead to further cooperation and policy advances, including on sustainability and resiliency issues worldwide.

Southern Hemisphere Winter Solstice

DIVERSE + DROUGHT RESISTANT PLANTING TYPOLOGIES

OPTIMIZED WINDOW-WALL RATIO

SELF-SHADING FACADE

Southern Hemisphere Winter Solstice

DIVERSE + DROUGHT RESISTANT PLANTING TYPOLOGIES

OPTIMIZED WINDOW-WALL RATIO

SELF-SHADING FACADE

Southern Hemisphere

Summer Solstice

December 21

OUTDOOR GATHERING SPACES

RAINWATER + GREYWATER REUSE

PHOTOVOLTAIC ROOFS + CANOPIES

REUSE OF BURLE MARX COURTYARD

VEGETATED ROOFS

SHADED + LIGHT COLORED WALKWAYS

SPORT COURTS FOR HEALTH + WELLNESS

Responding to the site’s most challenging conditions—the climate’s intensely wet and dry seasons—the re-introduction of droughttolerant Cerrado plants represents a naturally resilient solution.

Recycling HVAC condensate and retaining stormwater on-site for irrigation further helps the embassy weather the drier months. These efforts keep the non-Cerrado gardens verdant year-round while reducing water consumption for irrigation by over 50 percent compared to the standard green building (LEED) baseline. Moreover, the embassy’s use of low-flow fixtures is estimated to reduce indoor water consumption by more than 40 percent relative to the LEED baseline.

While many of these interventions may go unnoticed day-to-day, locally sourced building materials, including jatoba wood and emerald marble, feature prominently throughout the embassy, demonstrating and cultivating best practices in sustainability within the diplomatic community and beyond.

Electric vehicle charging stations installed on site support lower-emission commutes to and from the embassy, deepening the mission’s commitment to a greener future.

The new embassy visibly exhibits how natural and built systems can work together to improve human comfort and resiliency. Both living trees and the finely engineered façade, for example, provide shade—contributing to creating cooler spaces and lowering operational carbon emissions.

Above: An analysis of the building’s average annual illuminance determined that internal blinds would rarely need to be drawn, with no space being “overlit” over the course of a year.

Below: An axonometric diagram of the north-facing façade demonstrates how the chancery’s deep structural fins and horizontal stepping prevent the interior from being too bright, despite the harsh sun from this direction.

The optimized light levels produced by the embassy’s self-shading fins reduce solar heat gain and allow the majority of staff workstations to be located within three meters of the façade, reducing electricity use for lighting. Outside, the high percentage of non-absorptive surfaces across the entire site, created through the abundance of vegetation and light-colored pedestrian hardscapes, reduces the heat island effect and creates a comfortable outdoor environment.

Further showcasing the embassy’s commitment to advancing ecodiplomacy goals, the design is estimated to achieve 20 percent regulated energy savings relative to an industry standard baseline, ASHRAE 90.1-2013. These savings stem from dedicated outdoor air systems and chilled beams, which decouple ventilation from conditioning, as well as LED lighting with daylight sensors. With the addition of a large photo voltaic array covering various roof structures, the project should achieve more than 45 percent regulated energy savings relative to the baseline for typical new construction.

Conserving and adapting existing structures is inherently a sustainable act, generally saving between 50 and 75 percent of embodied carbon emissions when compared to constructing a new building. Restoring and reactivating the embassy’s original Burle Marx courtyard and its structures, now more than sixty years old, allows new generations to enjoy this culturally significant landscape and understand the environmental value of adaptive reuse.

Taken together, the project’s sustainable strategies allow it to target a goal of LEED Silver at minimum through the U.S. Green Building Council’s Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) green building program, as well as the local environmental goal of PROCEL certification.

Screens, fans, greenery, and an open-air design help passively lower energy consumption while providing a pleasant climate for gathering at the restored Burle Marx courtyard.

The planning, design, and construction of a U.S. diplomatic facility only happens with the contributions of many. We extend particular thanks to the OBO staff and leadership from real estate through operations and to our partners in Diplomatic Security, the Bureau of Western Hemisphere Affairs, and Embassy Brasília who contributed to making this safe, secure, functional, and resilient platform a reality. This collective team has ensured that this new U.S. diplomatic campus represents American values and the best in American architecture, design, engineering, technology, sustainability, art, culture, and construction execution. Without their diligent work and expert advice, this project would have not been possible.

Ambassador William H. Moser J. Douglas Dykhouse Director, Overseas Buildings Operations Principal Deputy Director, Overseas Buildings Operations

James Burnett FASLA

Peer from Office of James Burnett

Joshua David

Peer from World Monument Fund

Julie Snow FAIA

Peer from Snow Kreilich Architects

Design Team

Studio Gang

Lead Architect

KCCT Associate Architect

Atria Local Architect

OLIN Landscape Architect

Engineering & Consultant Team

Thornton Tomasetti

Structural, Façade, & Blast Engineer

Arup

MEP, Acoustical, AV, & Lighting Engineer

Langan

Civil Engineer

Atelier Ten Environmental Engineer

Mason & Hanger

Telecom & Secure MEP Engineer

Jensen Hughes

Security, Fire Protection, & Life Safety Engineer

Hopkins Food Service Consultant

Morris Wade Associates / Dharam Consulting

Cost Management

“Working in Brasília is a dream for architects and builders around the world, and we are proud to continue the careful planning and timeless design found throughout the city. With preservation and restoration of the Burle Marx courtyard, we will celebrate our history as the first embassy in the city, while the new buildings will enable the U.S. Mission Brazil to grow and adapt for decades to come. Whether our diplomatic partners are looking to host dignitaries on the landscaped terraces or holding economic symposia in the gallery and conference rooms, this project will be a stage from which the United States and Brazil can share the amazing work we do together.”

Ambassador William H. Moser DirectorOverseas Buildings Operations

November 2022

All sketches are the work of Jeanne Gang and are courtesy and © Jeanne Gang. Unless otherwise noted, all other images are courtesy and © Studio Gang.

Inside Front Cover: Roberto Burle Marx, Instituto Burle Marx; Page 4: (t) Marcel Gautherot, Instituto Moreira Salles Collection; (b) Companhia Urbanizadora da Nova Capital do Brasil (Novacap); Page 5: (t) (bl) Companhia Urbanizadora da Nova Capital do Brasil (Novacap); (br) Arquivo Público do Distrito Federal; Pages 6–7: Joana Franca; Page 8: (t) Arquivo Nacional; (b) Archival postcard; Page 9: McLeod & Ferrara Architects; Pages 10–11: (l) (tr) Archive of the Office of Foreign Buildings; Page 12: Archive of the Office of Foreign Buildings; Page 13: (t) Archive of the Office of Foreign Buildings; (b) Archive of Luiz Correia de Araújo; Pages 14–15: (tl) (bl) Companhia Urbanizadora da Nova Capital do Brasil (Novacap) (cl) (c) M. Fontenelle, Companhia Urbanizadora da Nova Capital do Brasil (Novacap); Pages 18–19:

OLIN; Page 35: Mark Niedermann; Page 44–45: (b) Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária (Embrapa); Pages 48–49:

OLIN; Page 54: George Everard KidderSmith, Museum of Modern Art; Page 58: Fundação Athos Bulcão; Page 59: (bl) Fernando Stankuns; (bc) Donatas Dabravolskas; (br) Marcos Vinícius Bessa/ AIG-MRE; Page 65: Atelier Ten; Inside Back Cover: Edgard Cesar, Fundação Athos Bulcão

Barber, Daniel A. “Le Corbusier, The Brise-Soleil, and The Socio-Climatic Project of Modern Architecture, 1929–1963.” Thresholds, no. 40 (2012): 21–32. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43884894.

Bergdoll, Barry, Carlos Eduardo Comas, Jorge Francisco Liernur, and Patricio Del Real. Latin America in Construction: Architecture 1955-1980. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2015.

Doherty, Gareth, and Leonardo Finotti, eds. Roberto Burle Marx Lectures: Landscape as Art and Urbanism. Zürich: Lars Müller Publishers, 2018.

Fellet, João. “A história do quilombo que ajudou a erguer Brasília—e teme perder terras para condomínios de luxo,” BBC News Brasil, July 1, 2018. https://www. bbc.com/portuguese/brasil-44570778.

Staübli, William. Brasília. New York: Universe Books, Inc., 1965.

Strassburg, Bernardo B. N., et al. “Moment of truth for the Cerrado hotspot.” Nature Ecology & Evolution 1, 0099 (March 2017). https://doi. org/10.1038/s41559-017-0099.

Tavares, Paulo. “Brasília: Colonial Capital.” e-flux, October 2020. https:// www.e-flux.com/architecture/the-settlercolonial-present/351834/braslia-colonialcapital.

U.S. Embassy Brasília is a publication by Studio Gang and the U.S. Department of State Overseas Buildings Operations.

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without permission from U.S. Department of State Overseas Buildings Operations.

Every reasonable attempt has been made to identify owners of copyright. Errors or omissions will be corrected in subsequent printings.

Right: Athos Bulcão’s 1972 tile panel for the SQS 316 Kindergarten in Brasília. Part of the city’s modernist design history, Bulcão’s graphic mosaics reinterpret the Portuguese tradition of tin-glazed tiles (azulejos).