DISCOVERY

Profile of a young hunter

MUSIC

Interview with a jazz virtuosa

MASTERY

Craft beer pioneers

Profile of a young hunter

MUSIC

Interview with a jazz virtuosa

MASTERY

Craft beer pioneers

info@plose.org

www.plose.org

Contributors

1 Journalist Barbara Bachmann wanted to understand what attracts young people to hunting, although she herself would never be able to shoot a wild animal. For her report (p. 20), she headed out with a gamekeeper in search of some common ground – and a herd of chamois.

2 COR photographer Caroline Renzler had done her weekly shop before visiting traditional corner shop Market Oberhofer in Vals/Valles to take photos for our article on p. 30. Nevertheless, she still came away with a bag full of goodies: two Christmas tree baubles, her favourite chocolate, a nourishing skin balm and a magnet as a souvenir of the photo shoot.

3 At first, she said she was the wrong person for the job, as she didn’t even like beer all that much. But now, after eventually agreeing to write our article introducing the Eisacktal valley’s new craft beer pioneers (p. 42), COR author Bettina Gartner has changed her mind: “Never in my wildest dreams had I imagined that beer could taste so good and that there could be so many different flavours.” Cheers!

Cor. Il cuore. Das Herz. The heart. As it beats, it unites our past, present and future. What is life? The life you’ve already lived? The life you’re currently living? Or the life that’s still to come? It’s probably best described as a mixture of all three. The more we remember the past, understand it and learn from it, the better equipped we are to deal with the present and the more optimistic we can feel about what lies ahead. The stories in this issue reflect this.

Happy reading!

The Editorial Team

PUBLISHERS

Brixen Tourismus Genossenschaft Tourismusgenossenschaft Gitschberg Jochtal Tourismusgenossenschaft Klausen, Barbian, Feldthurns und Villanders Tourismusgenossenschaft Natz-Schabs Tourismusverein Lüsen

CONTACT info@cormagazine.com

EDITORIAL TEAM Exlibris exlibris.bz.it

PUBLISHING MANAGEMENT

Valeria Dejaco (Exlibris)

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Lenz Koppelstätter

ART DIRECTOR Philipp Putzer farbfabrik.it

AUTHORS

Valeria Dejaco, Lisa Maria Gasser, Bettina Gartner, Amy Kadison, Lenz Koppelstätter, Debora Longariva, Judith Niederwanger and Alexander Pichler (Roter Rucksack), Silvia Oberrauch

PHOTOS Cover photo: Michael Pezzei; Florian Andergassen (6-7), Leonhard Angerer (68-69, 72), archives, Albert Ceolan (41), Peter Daldos (41), Nicho De Biasio (16), Markus Denicolò (16), Frauenarchiv Bozen – Bestand Frauen für Frieden (71), Frei & Zeit (15), Alex Filz (17, 61), Hannes Fistill (61), Wolfgang Gafriller (15), Matthias Gasser Photography (79), Mirja Kofler (3), Manuel Kottersteger (61), Tourismusverein Lüsen (79), Alex Moling (12-13), Helmut Moling (41, 65), Tourismusgenossenschaft Natz-Schabs (63), Kloster Neustift (40-41), Hannes Niederkofler (8-9, 14, 78), Paragliding Gitschberg (61), Michael Pezzei (18-19, 20-28, 52-60), private, Caroline Renzler (3, 30-31, 32-39, 42-49, 62), Roter Rucksack/Judith Niederwanger & Alexander Pichler (82), J. Konrad Schmidt (64), Patrick Schneiderwind (73), Patrick Schwienbacher (15), Shutterstock/Svet La (14), Shutterstock/clarst5 (24), Shutterstock/Dario Pautasso (27), Shutterstock/zlikovec (27), Shutterstock/01elena10 (42), Shutterstock/sonsart (77), Shutterstock/Sompao (81), Shutterstock/ Annabell Gsoedl (81), Shutterstock/Tatiana Diuvbanova (81), Tiberio Sorvillo (10-11, 40), Annemone Taake (17), Konstantin Volkmar (16), Wikimedia Commons/Llorenzi CC BY-SA 3.0 (74), Günther Willeit (65), Harald Wisthaler (80), Oskar Zingerle (14)

ILLUSTRATIONS

Cristóbal Schmal (4, 66)

TRANSLATIONS AND PROOFREADING

Exlibris (Valeria Dejaco, Alison Healey, Debora Longariva, Milena Macaluso, Charlotte Marston, Federica Romanini, The Word Artists)

PRINTED BY Lanarepro, Lana

6 Old Ideas – Reimagined!

New and Approved

18 Q&A with...

Martina Prast Hofer, youth leader at the Villanders whip cracking club

20 Forests, Fresh Air and Fulfilment

Out and about with gamekeeper Alex Bergmeister

30 Safe from SabreToothed Tigers

A tribute to corner shops

32 Alpine Roots Run Deep

An interview with musician Ruth Goller

40 Spectacular Places

Neustift Abbey

42 Brewed from the Heart

We meet craft beer pioneers

50 Letter by Letter

A piece of history

52 Guardian Angels of the Mountains

Three winter sports experts tell their stories

61 Ready for Action!

In the safe hands of professionals

62 The World of Krapfen Pastries

Five delicious varieties

64 Soaking up the Sun

A visit to the Pacherhof winery

66 A Beginner’s Guide to South Tyrol

Part 6: Breaking Bread

67 A Short Dictionary of South Tyrolean

Understand what the locals say

68 A Cold Conflict

Searching for traces of a former NATO base

76 Beautiful Things

Products from the region

78 Favourite Spots

Where you can feel at one with nature

82 A Well-Deserved Break

The story behind a favourite photo

Farm to table, zero food miles. These cool concepts may sound new, but they’re far from it. The region’s farmers and innkeepers can still remember how things were before. Today, new yet old, tried-and-tested local supply chains are re-appearing. Food is being served directly from the fields – like here in Natz/Naz – as well as from the meadows, mountains and local waters. Because it’s healthy. And tastes delicious!

From fresh, imaginative new dishes to leisurely winter hikes in the mountains and long bike rides in the valley, the best discoveries are sometimes waiting for you where you’d least expect them. And they’re all the better for it

Winter is for taking things slowly. Today’s tourists are embracing a different side to the magical colder months. One that does them a world of good. So take your time to admire panoramic views, like those you can enjoy while snowshoeing on the Rodenecker and Lüsner Alm mountain pasture.

A generation of young, talented chefs is emerging. They often dive into their grandmothers’ recipe books for inspiration and reinvent the old dishes they find there. Like here in Brixen/Bressanone, where the team at Vitis wine bar wow their guests with light summer dishes.

Sleek like a racing bike, robust like a mountain bike and comfortable like a trekking bike, gravel bikes are all the rage. They are ideal for long rides, short leisure trips and multi-day bikepacking tours, far away from road traffic. For example, on the valley cycle paths running up and down the Eisacktal valley.

Did

You Know That...

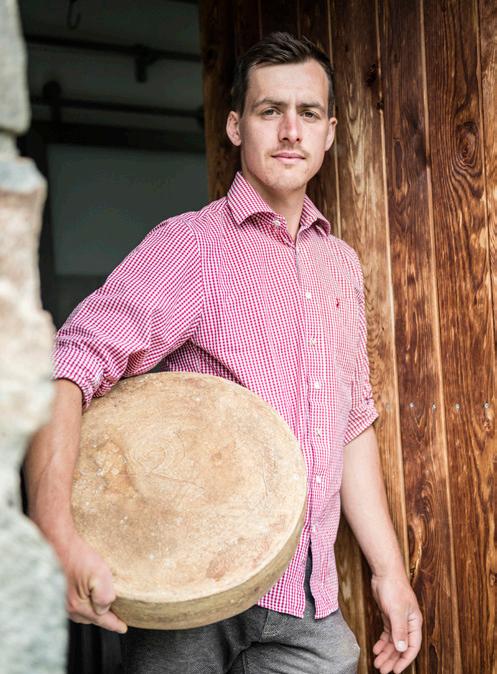

...a certified cheese sommelier is behind the award-winning cheeses produced at the Kreuzwiesen Alm mountain lodge in Lüsen/Luson?

900,000

THAT’S HOW MANY apple trees blossom in the 270 hectares of orchards in Natz-Schabs/ Naz-Sciaves every spring. The plateau’s villages – Natz/Naz, Schabs/Sciaves, Raas/Rasa, Viums/Fiumes and Aicha/Aica – celebrate the awakening of spring in late April and early May with the annual Blossom Weeks festival, which includes orchard tours, herb walks and tasting sessions at nearby farms. As part of the event, local restaurants also serve deliciously light and fresh flower- and herb-inspired dishes. The highlight is the Blossom Festival in Natz on 1st May, where you can try local specialities and listen to live music while enjoying the mild spring temperatures.

natz-schabs.info

JOHANNES HINTEREGGER, a farmer at the Zalnerhof farm in Lüsen with a passion for dairy, makes cheese and matures it on spruce boards in an earth cellar on the Lüsner Alm mountain pasture, where his brown cows graze in summer. You can visit the alpine dairy at the Kreuzwiesen Alm and watch as he uses old recipes or his own new, creative ideas to make eight different types of cheese from the fresh raw milk produced that day, natural rennet and salt. His varieties include the intense, cone-shaped Lüsen Ziggokas as well as a South Tyrolean grey cheese and an alpine cheese infused with pine needles, both of which won Silver at the International Alpine Cheese Olympics. All the varieties bear the Roter Hahn (Red Rooster) quality seal, which means they meet strict quality standards. And as a cheese sommelier, Johannes is able to recommend the perfect wine to accompany each of his cheeses.

kreuzwiesenalm.com

1

Adventure nature trail, Rodeneck/Rodengo

Children will love this woodland adventure trail, which is fun for all the family. Here, you can balance on tree trunks, build fairy houses from moss and branches, and even have a pine-cone throwing competition as you wander through the woods. The circular route runs from the Ahner Berghof farm to a nearby reservoir and back again and you can learn plenty about trees and forests along the way. The start of the route can be easily reached by the Almbus, which runs once an hour.

Start and end point: Ahner Berghof, Rodeneck

Duration: 40 minutes

Distance: 1.5 km

Elevation gain: 67 m

Highest point: 1,396 m

Hiking in the foothills – our top tips for spring and autumn hikes in some fascinating locations

2

Gereuther Höfeweg farm trail, Brixen/Bressanone

Despite the tough conditions and steep alpine meadows, generations of farmers have lived off the land on the Pfeffersberg mountain slope to the west of Brixen. A new circular trail now connects nine of their rustic historic farms, so visitors can witness how farming traditions are still lovingly upheld. Don’t miss the old sawmill that had fallen into disrepair but has now been painstakingly restored.

Start and end point: Gereuth/Caredo near Tils/Tiles above Brixen (can also be started from several other points)

Duration: 2 hours

Distance: 5.3 km

Elevation gain: 280 m

Highest point: 1,429 m

3

Waterfalls and Dreikirchen circular hike, Barbian/Barbiano

Now including some newly installed resting points, this easy circular hike takes you from the village of Barbian to the spectacular Barbian waterfalls, past the architecturally intriguing Hotel Briol and on to Dreikirchen/Tre Chiese. Along the trail and in the woods, you’ll find wooden benches and platforms for sunbathing, picnicking and staring dreamily into the valley.

Start and end point: Barbian village centre

Duration: 4 hours

Distance: 8.6 km

Elevation gain: 560 m

Highest point: 1,353 m

New additions to the town’s thriving gastro scene

12:00pm

MEDITERRANEAN TAPAS AT SOLEY

Inspired by relaxed Mediterranean dining, the idea behind the sharing tables at the new Soley restaurant is to serve small plates and light bites so that everyone can help themselves. The dishes are best sampled alongside a chilled glass of Eisacktal valley white wine.

soley-suites.com

5:00pm

LATE-19TH-CENTURY CHARM AT THE JAROLIM

Late afternoon is still early enough for coffee but also late enough for an aperitif. Whether you prefer an espresso macchiato or a negroni sbagliato, you can now enjoy a drink in style at the lovingly renovated art nouveau bar of Hotel Jarolim, which dates back to 1891.

hotel-jarolim.it

8:00pm

MONASTIC SIMPLICITY AT FINK

With its modern yet traditional design, the recently renovated historic fink hotel is the ideal spot to spend a relaxing evening. Here you’ll find old vaults, light wooden tables and a small regional menu featuring lots of seasonal vegetables and a few select meat-based dishes inspired by the food once served to the monks and nuns of this pious episcopal town.

fink1896.it

SITTING ATOP a rocky outcrop high above Klausen/Chiusa stands an imposing abbey that has inspired legends aplenty. Over the centuries, Säben Abbey –which dates from 1686 – has been known by several names, including the Holy Mountain, the Cradle of Christianity in Tyrol and even the Acropolis of Tyrol. The two-kilometre, 40-minute climb to the abbey from Klausen town centre runs past Branzoll Castle and was once a spiritual pilgrimage route. Since 2023, visitors to the site can listen to a new audio guide covering 10 points of interest along the walking route up to the abbey. Read by South Tyrolean actors and authors, the guide tells stories about life in the abbey, archaeological finds and hidden art treasures. It can be played free of charge on your smartphone and is available in German, Italian, English and Ladin.

“I’d love to play the first male paramour in Jedermann (Everyman) at the Salzburg Festival,” says actor TOMMY FISCHNALLER-WACHTLER. “Swapping the genders of the characters or cast would be exciting and in keeping with the times.” Tommy, who was born in Brixen/Bressanone, recently received the Nestroy Theatre Prize for Best Newcomer for his role as Effi Briest at the Bronski & Grünberg Theatre in Vienna, Austria.

The actor first performed on stage at the age of 14 with the Klausen/ Chiusa-based ensemble Rotierendes Theater. After completing his studies at the Music and Arts University of the City of Vienna, he also began acting on film. The 27-year-old has been a permanent member of the ensemble at the Tyrolean State Theatre in Innsbruck, Austria, since 2023 and is playing the lead role in Café Schindler in 2024. To relax, he loves returning to his home village of Raas/Rasa: “I go back home to spend time with my family. My parents’ house, nature and the peace and quiet are oases of energy for me.”

A growing number of hotels are being awarded the official South Tyrol Sustainability Label in recognition of their commitment to the environment. However, individual holidaymakers can make a difference too. Read our 5 tips for a more sustainable holiday:

Pack a reusable drinks bottle. Hotels have to throw away a surprising amount of rubbish left behind by their guests, including mountains of plastic water bottles. You can help put a stop to this by packing your own drinks bottle and refilling it with the high-quality spring water readily available across the region.

Try local wine. Instead of French white wine or red wine from Tuscany, choose a wine made on your hotel’s doorstep like an elegant Sylvaner from the next-door village or a rustic Portugieser from the neighbouring farm. The region’s knowledgeable restaurateurs and sommeliers will gladly recommend the right local wine to accompany every dish.

Give your car a break. Even if you travel to South Tyrol by car, you can leave it parked up on arrival and use public transport for your days out hiking, skiing or exploring. Bus and train travel is included in your tourist card and most places are very well connected.

Eat seasonally. Be it strawberries in spring, chanterelle mushrooms in summer or chestnuts in autumn, all locally grown ingredients are seasonal by definition and taste all the better for it. If you’re self-catering, you can support regional growers by shopping for groceries at the farmers’ market instead of the supermarket. Plus, you can support sustainable supply chains by looking for restaurants that cook with locally grown ingredients.

Choose veggie options. In the past, both Alpine and Mediterranean cuisine did not include much meat. Little wonder then that the region’s restaurants cater so well for vegans and vegetarians. Why not give a veggie dish a go when eating out?

Martina Prast Hofer, 42, who runs the youth training sessions at the Mir Flonderer Goasslschnöller whip cracking club in Villanders/Villandro

Interview — LISA MARIA GASSER Photos — MICHAEL PEZZEIWhat skills do you need to crack a whip properly?

Having no fear is absolutely crucial. Beginners start by learning a basic move, which involves circling the whip in a horizontal figure of eight above your head, pulling it quickly backwards and cracking it. It’s important to keep your legs and hips swinging in the same rhythm. Then you’ll make a lovely loud sound. Once you’ve got the hang of the technique, practice makes perfect. At championships, the judges award points for volume, rhythm and posture.

What makes whip cracking so popular?

It’s an age-old pursuit. You get to spend time outdoors, burn off some energy and help keep a traditional custom alive. Our

club is very close knit. It includes entire families, and members of all ages come together to support and help each other. When we take part in competitions, for instance, the girls all plait each other’s hair. For performances, the girls and boys wear white and light green checked shirts, jackets with our club’s logo and blue aprons with their names embroidered on. The majority also wear lederhosen or jeans.

You teach the art of whip cracking to children. But what can adults learn from the children in your group? Children have a very relaxed approach and aren’t scared to get stuck in and give everything a go. In contrast, adults are often afraid of getting injured by accidentally whipping themselves around the ears. That’s why our older members tend

to duck their heads. The children also take part in championships. This spurs them on to practise and train even harder because they want to show off what they can do. Winning a cup or medal makes them feel really happy and proud.

Goasslschnöllen (whip cracking) is an Alpine custom that shepherds and carriage drivers once used to communicate with each other and their animals. The “Goassl” (whip) consisted of a twisted leather or hemp rope attached to a leather or wooden handle. The shepherds and carriage drivers would swing the whip jerkily through the air creating a loud cracking sound (known as the “Schnöll”) in order to make themselves heard. Today, whip cracking has evolved into a popular sport enjoyed by adults, young people and children alike. In South Tyrol, there are over 30 whip cracking clubs whose members perform at traditional events and compete in regional and world championships across all age categories.

Want

A growing number of young South Tyroleans are taking up hunting. Why are they so attracted to it? And what does it mean to be a hunter today? We head out into the Pfunderer mountains in pursuit of answers with gamekeeper Alex Bergmeister

COR reporter Barbara Bachmann was a vegan for many years and hunting has always been alien to her. Why is it currently having such a huge resurgence? “For the same reason people are becoming vegan,” says Alex Bergmeister. Hunters and vegans are both motivated by their shared dislike of intensive livestock farming and blind consumption.

ALEX BERGMEISTER, 27, is holding his binoculars up to his eyes, his gaze fixed straight ahead before turning slowly left and then right. “They must be here somewhere,” he says into the silent countryside all around him. “If you wait here long enough, you’ll usually see up to 100 chamois,” he explains. Just a few hours earlier, another spot he visited had been teeming with local wildlife – chamois, marmots and deer, including some stags. But now, on this unseasonably cold afternoon for late August, there are no signs of anything.

We’re in the Steindlerberg area at the far end of the Pfunderer valley, which is arguably one of the most remote places in South Tyrol. The summits here are overgrown with grass right to the very top and the landscape is reminiscent of The Shire in The Lord of the Rings, only we were greeted by whistling marmots instead of hobbits. Wearing sturdy hiking boots and carrying a rucksack packed full with bandages, a penknife, gloves, a hat and a second jacket, Alex strides purposefully through the land of his childhood. As he clambers over streams and past twisted larch trees bent double by the wind, his green clothes provide him with almost perfect camouflage against his surroundings. He finally comes to a stop at a large, flat stone and takes a seat.

In his work as a gamekeeper, Alex sees more wild animals than people. He’s passionate about hunting. I, on the other hand, haven’t eaten meat for years, still think there are lots of benefits to leading a vegan life-

style and wouldn’t dream of killing an animal. Years ago, I raised an injured fawn like I would a child. It had lost its right hind leg after being run over by a mower and I spent months cleaning its wound and bottle feeding it with goat’s milk. And now I’ve just spent the past hour tracking a gamekeeper and hunter’s every turn. You’re probably wondering what possessed me. But I’m fascinated to find out why a young person like Alex is so captivated by hunting when I mainly associate it with shot animals.

Earlier, as we were driving up the stony road to the forest in his black VW Tiguan, the sounds of a Styrian harmonica playing on the radio, Alex started to explain. “My dad is a hunter, and I always wanted to be just like him.” Growing up, he accompanied his father into the forest whenever he could. And later, as an adult, he began to learn all about the local flora and fauna, as well as about hunting rifles and the laws around them. Like all young people with an interest in hunting, he says that he was very careful not to do “anything silly” because any prior convictions would have prevented him from gaining his firearms licence. In 2015, he passed his hunting exam and began hunting.

I ask him what his best experiences have been as a hunter so far. Instead of immediately reminiscing about one of his own triumphs, Alex first tells me about the time one of his friends shot a wild boar right in front of him. His own greatest trophy was an →

“My dad is a hunter and I always wanted to be just like him,” says Alex. In 2015, he passed his hunting exam after learning all about the local flora and fauna, as well as about hunting rifles and the laws around them.

Gamekeepers are more than just hunters. They are responsible for protecting animals and nature by monitoring the entire hunting ground, taking steps to combat poaching, reporting all violations of the law and handing out the appropriate penalties. The most important aspect of their work is observing the wild animals, their population sizes and state of health. This includes counting or estimating their numbers as accurately as possible. They also help to implement hunting quotas and maintain the hunting ground.

More information: jagdverband.it

As a gamekeeper, Alex is responsible for the hunting ground in Pfunders, Mühlbach and Mittewald. Whenever he looks down into the valley, he has no regrets about his career choice.

“Even though I often have to get up at 4am, I feel so much freer than I did before.”

18-year-old female chamois. When he shot her, he was barely older than the animal herself. “I was young and fanatical and went out hunting every weekend, even in rain and snow,” he recalls. He then explains how the older the animal, the cleverer it is because it knows to avoid places where it has been in danger before.

Still seated on the large lookout stone, we gaze down at the meadows full of lady’s mantle, yarrow and blueberries. I learn that rich soil provides game animals with all the nutrients they need. “There’s one,” says Alex suddenly. He’s spotted our first chamois. He passes me the binoculars and digs out a large spotting scope from his rucksack to get a better view. The animal’s hide is still light, but soon it will turn darker to help it keep warm over winter. Alex explains to me that the speed at which the hide changes colour is an indication of how healthy the animal is.

Together with his father, Alex is responsible for the hunting ground in Pfunders/Fundres, Mühlbach/Rio di Pusteria and Mittewald/Mezzaselva, which covers around 20,000 hectares and is used by roughly 150 hunters. I ask him what he enjoys most about his job. “I trained as a carpenter. I would earn more working on a building site, but I wouldn’t be as happy,” he says, adding that whenever he looks down into the valley, he has no regrets. “Even though I often have to get up at 4am, I feel so much freer than I did before.” So what’s the worst part of his job? “Having to hand out penalties,” he replies, for instance when hunters accidentally shoot a buck instead of a doe.

Left

Has society’s view of hunters changed over the years? According to Alex, some hunters used to sit proudly with blood-stained fingers in their local inn after a hunt. Today, there are very strict rules around hunting. “Killing is part and parcel of it, but it’s only a small element of what it means to be a hunter.” Hunters are also responsible for maintaining balance in the ecosystem.

Below

The remote Pfunderer valley is reminiscent of The Shire in The Lord of the Rings, only it is home to whistling marmots instead of hobbits.

In addition to monitoring the wild animals, Alex is required to count or rather estimate their numbers as accurately as possible. According to Alex, there are at least 700 chamois across the entire Pfunderer high mountain range, which is considerably more than the numbers of red and roe deer. Of these 700, hunters are permitted to shoot around 70 each year, half of which are bucks and half of which are does without kids. “Shooting a doe with kids is definitely frowned upon among hunters,” says Alex, adding that this has always been the case even in days gone by.

Talking of days gone by, I ask Alex whether society’s view of hunters has changed over the years. He tells me that it was once common for hunters not to wash their hands after a hunt and to spend hours sitting with bloodstained fingers in their local inn. Back then, hunters were glorified and viewed with pride, and the pursuit was accepted by society without discussion. Poaching was also rife, and legends abounded. “Today, the laws governing the illegal possession of firearms are rightly very strict,” says Alex. “And anyone carrying a rifle must have no trace of alcohol in their system.”

Undeterred by the drop in temperature, we both put on another jacket and continue to keep watch from our lookout post. “Game animals prefer warmer weather too,” Alex jokes. I want to know whether young hunters are any different to those from older generations. “Young hunters appreciate how lucky they are to still be able to hunt,” he replies. He explains that they are fully aware of how mounting criticism could result in hunting being abolished sooner or later. Instead of telling gory stories, young hunters now post photos of their kills on social networks like Instagram. They don’t want to provoke people unnecessarily, so they are much more likely to post aesthetic photos of dead animals that, at first glance, look as if they are sleeping.

“Killing is part and parcel of hunting,” says Alex. “But it’s only a small element of what it means to be a hunter.” Responsible hunters also help maintain balance in the ecosystem. They relieve animals of their suffering following road accidents, feed animals and give them vital salt to prevent them from starving to death in snowy winters, and help to bring fawns – like the one I hand-reared – to safety by carefully removing them from long grass before the summer mowing season in such a way that their mothers don’t abandon them. And yet, after all that, they still shoot them. I ask Alex what it is about shooting animals that is so alluring. “It’s the sense of achievement. You’ve finally outwitted the animal, often after being run around in circles by it.” I learn that the world of hunting is full of rituals. After delivering the fatal shot, hunters pick up a twig, break it in half and place it in the animal’s mouth to give it “its last bite of food”. They then place a second twig into the right-hand side of their hat. Although I can’t understand the satisfaction hunters feel after shooting an animal, I am at least pleased that Alex seems to respect the living creatures he hunts.

“There was a time when only a few young people were interested in hunting,” he says. Recently, however, he’s witnessed a real surge in popularity. Why is hunting having such a huge resurgence? Alex’s answer astounds me. “For the same reason people are becoming vegan,” he replies. Excuse me? “Hunters don’t want to give up eating meat, but they want to know where it comes from and are prepared to take action into their own hands. They don’t just eat the meat but shoot the animal themselves and prepare and cut up the carcass to make products like smoked dry sausages.” In other words, hunters and vegans are both motivated by their shared dislike of intensive livestock farming and blind consumption. I can certainly see the logic in that argument.

As well as being his place of work, Pfunders is Alex’s local hunting ground, but he no longer hunts here, since gamekeepers have to be impartial. He only uses his rifle to shoot a sick or injured animal. “My work is just as fulfilling as hunting,” he says, before his attention is caught by a pair of baby chamois. No matter how many he’s seen over the years, the sight still brings him joy. Instead of talking, we gaze spellbound as a herd of around 20 chamois comes into view and starts grazing, the little ones sticking closely to their mothers. Mesmerised, Alex and I have finally found some common ground. If I’d been on my own, I would probably have turned around much sooner and missed this wonderful sight. I now know that patience is best learnt from a hunter.

+ Recommended hike Pfunders/Fundres mountain lodges circular trail

This circular route from the hamlet of Dun (1,468 m) takes you through green mountains to the Egger-Bodenalm and Gampiel Alm farms, the latter of which offers panoramic views across the Pfunderer valley and Rodenecker and Lüsner Alm mountain pasture to the Peitlerkofel mountain. Both farms are very family-friendly, and the forest and mountain tracks are easy to manage for children used to walking.

Duration: 3 hours 40 minutes

Distance: 8.9 km

Elevation gain : 720 m

Highest point: 2,050 m

outdooractive.com/r/16570958

The tranquil Pfunderer mountains are fantastic for non-hunters to explore too, such as on a hike through the local pastures. Take a pair of binoculars with you to look for chamois like a gamekeeper.

The South Tyrol Sustainability Seal identifies destinations, accommodations and restaurants that actively contribute to conscious travel. Get to know which they are and walk with South Tyrol towards a sustainable future.

suedtirol.info/sustainable-holiday

An Aunt Emma shop (Tante-Emma-Laden) is what German speakers affectionately call local corner shops. Here, our author pays tribute to how these magical places bring villages together, create a comforting sense of security and provide continuity in our otherwise rapidly changing world

As I step inside, look around and greet the man behind the sausage counter, I have a funny feeling that I’ve been here before. I’ve visited many Aunt Emma shops in the past, but this is the first time I’ve set foot in Market Oberhofer in Vals/Valles. That said, once you’ve seen one corner shop, you’ve seen them all, so similar are they in terms of fittings, products and clientele. Large supermarkets are anonymous and cold, but here I feel at home.

A village shop like this provides continuity in our otherwise rapidly changing world. The fixtures have stayed largely the same over the years and – with the exception of a few organic, gluten-free and soya products that have made their way on to the shelves – the range of goods pays very little heed to current trends. That’s part of what makes Aunt Emma shops so magical. Here, you don’t have to decide between dozens of pasta shapes and an absurd number of yogurts. The shops likely stock fusilli and spaghetti as well as low-fat and full-fat yo -

gurt and possibly a soya alternative. And that’s it. This take-it-or-leave-it approach is so refreshing in a world where you are constantly faced with a barrage of decisions due to there being so much choice. Should I watch the new Netflix series, a film on Amazon Prime, a documentary on catchup or just zap through the TV channels? Do I need a shampoo for fine, greasy, frizzy or dry hair? The shampoo aisle often makes me want to literally tear my hair out. But in an Aunt Emma shop, I can simply pick up the one shampoo available, suitable for all hair types, and just like that, problem solved!

5 6 7

If we are to believe Yuval Noah Harari, the world-renowned Israeli historian and best-selling author of Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, the existence of Aunt Emma shops is down to evolution. One of Harari’s theories is that our ancestors didn’t just develop language to warn each other of an approaching sabre-toothed tiger, but rather that language primarily evolved for the purpose of gossiping because gossip seems to be the glue that binds groups of people together. And where exactly do people meet to catch up on the latest village gossip? In the village shop, of course! Where better to share news about births and deaths than among shelves stocked with nappies and memorial candles? Or to swap recipes and housekeeping tips among bread dumpling ingredients and cream cleaner? The village shop is a safe space where people can come together and chat without fear of being attacked by a sabre-toothed tiger.

If I received warning that our planet was about to be taken over by aliens, I’d seek refuge in an Aunt Emma shop!

1 — Proud managers Alfred Oberhofer and his niece Helena in their Market in Vals.

2 — A comb, nail file and brush – everything you need to look wellgroomed.

3 — The entrance to the private staff room behind the butter and yogurt.

4 — Tabloid press, mountains and plenty of gossip.

5 — Wire shopping baskets piled high as if in a still-life painting.

6 — An amusing souvenir of the Pope or a serious memorial candle? That’s for the customer to decide.

7 — Patriotic stickers featuring an emperor, eagle and edelweiss.

Acclaimed bassist Ruth Goller on swapping punk for jazz, her move from Brixen/Bressanone to London, composing as a child, a rebellious youth spent in idyllic surroundings – and music that sounds like home and comes right from the heart

Interview — LISA MARIA GASSERRuth, you describe yourself as quiet, calm and reserved. Would you say the same of your music?

RUTH GOLLER: My own music, yes. But in much of my other work, I really ramp up the energy. I used to play punk music, and I love loud, powerful sounds as much as I do soft, delicate ones. To me, there’s emotion in the music at both of these extremes.

You formed a punk band during your school years in Brixen. How did you first get into music?

My dad sang in choirs and played the clarinet in the local music group. My mum, on the other hand, was the most unmusical person I’ve ever known. But both my parents wanted their children to learn an instrument. I chose the

violin when I was six years old, and my older sister, Barbara, chose the piano. Like most children back then, I loved listening to music and was always recording songs off the radio from artists like Michael Jackson and Queen. What made me a bit different was that I also loved composing from a young age.

With a pen and paper?

No! We had a piano at home. I couldn’t actually play the piano, but I spent a lot of time tinkering about on it and improvising. I liked to do more than just play music from a sheet.

Is it true that you also couldn’t play guitar when you put together your punk band?

When we started out, none of us four girls knew how to play our instruments. We simply picked up the guitar, bass and drumsticks and had a go. I’ve always trusted my ear and my instincts!

When did you switch from guitar to bass?

I’ve always loved the deeper notes. One day, I spotted a second bass lying in the corner of the rehearsal space we shared with some other bands. I began experimenting with it and eventually started to write pieces for two basses and one guitar.

Was punk music your way of rebelling against your parents and your idyllic upbringing in South Tyrol?

Not consciously. I had a free and easy childhood and could do whatever I wanted. In Brixen, people recognised me because of my ripped trousers and red dreadlocks. I guess that made me rebellious. But I was able to be that person because my dad trusted me and didn’t put any constraints on me. I had more freedom than my friends, and that’s probably why I was a bit more extreme than them.

After you finished school, you swapped the serene tranquillity of South Tyrol for the hustle and bustle of London. What made you choose London specifically?

I could have ended up anywhere. After school, my friends all decided to study chemistry, maths or law. But I knew that I wanted to stand on the stage with my bass and my bandmates and make music. I just didn’t know how to make my dream a reality. At that point, I was completely self-taught, and I knew virtually nothing about music theory or how to actually play the bass properly. By chance, I heard about a small London music school for beginners. I gave them a call, sent them a cassette with some recordings of my punk band, and the rest is history!

Moving to a huge, strange city on your own when you were just 20 was a brave thing to do!

I was more extreme than my friends because I had more freedom than them.

Brave but exciting! As soon as I was accepted, I packed all my things together, put my amp, bass and suitcase into my car, and drove all the way from Brixen to London. I didn’t have anywhere to live at first, so I spent the first few nights sleeping in my Renault, which I’d parked up on Tower Bridge. I got a job in a bar so picked up English quickly, and after a year at the school, I had a good grasp of music theory, harmonics and different styles and techniques. Then, in 2002, I started studying jazz at Middlesex University in northwest London.

How did you make the transition from punk to jazz? Aren’t the two genres worlds apart?

Not to me. Growing up, I knew absolutely nothing about jazz. In fact, I only discovered it by chance in London when I was browsing through the music school’s audio library and came across American jazz musician John Coltrane. I fell in love with his music straightaway. It gave me such a sense of energy and freedom – just like punk music did. While studying in London, I also learnt all about the art of improvisation, which was something I’d been doing intuitively on the piano,

guitar and bass for years. That’s when I realised jazz was for me.

But you’ve never wanted to be pigeonholed?

No, I don’t like it when people ask me what type of music I make. My music is influenced by all the different genres I enjoy – from jazz and punk to techno and electronic music. And lots of improvisation, of course! I often start the writing process at home, simply by playing whatever comes to mind. Then, when I listen back to the recording, I find parts that I really like and compose a piece around them.

Is your state of mind reflected in your music?

Yes, always. That’s what I love about improvising. My music comes from deep inside me and mirrors what I’m feeling in the moment.

Are you not afraid of revealing your innermost thoughts and feelings? That’s art. It’s what we artists do.

Do you ever worry about how your music will be received?

A long time ago, I realised that I can’t control who likes and doesn’t like what I do. The only thing I can control is what

“When I was young, my grandma told me ghost stories from the

and from my

who was convinced that he saw dead people in the

Even now, I feel certain forces that spark my creativity.”

Listen to Ruth Goller’s latest solo album, Skyllumina, here:

I think about it. If people like or dislike my music, then so be it. Even if someone doesn’t like my music, that’s okay because it means I’ve still triggered their emotions. My solo project Skylla isn’t exactly what people would call popular music. It’s pretty unconventional.

Skylla is also the title of your first album. It’s a very mystical name. Are you inspired by mythological legends and figures?

Absolutely. I’m influenced by all the South Tyrolean myths that I grew up with and have loved reading ever since I was a child. When I was young, my grandma often told me ghost stories from the mountains and from my grandpa, who was convinced that he saw dead people in the woods. Grandma was a firm believer in ghosts, so, as children, we definitely believed in them too. Even now, I feel certain forces that spark my creativity. I can’t explain them, but they’re certainly there.

What else do you draw inspiration from when you are composing?

Life and all its experiences – from nature and music to the people I encounter along the way.

What do you say when somebody asks you where you come from?

I say that I’m from the Alps. I think that’s what characterises us as South Tyroleans the most. Mountains and landscapes define people more than borders.

You currently live on the outskirts of London, but regularly return to Brixen.

Since moving to London over 20 years ago, I’ve always come back to Brixen at least once a year for Christmas. These days, I return more often simply because I like spending time here.

What keeps you coming back to South Tyrol?

My sister lives in Brixen and we’re very close, especially since our parents passed away. We speak to each other every day and spend a lot of time in our father’s childhood home in Pufels/Bulla surrounded by nature and the mountains.

43, moved from Brixen to London in 1999 and studied at Middlesex University. She has played in a diverse array of successful punk jazz bands, releasing numerous albums with them. As a bassist, she has performed alongside many legendary musicians, including jazz giants like Marc Ribot and rock stars like Paul McCartney and Damon Albarn. In 2021, she released her solo album Skylla, which went on to receive huge international acclaim.The peaceful seclusion and tranquillity are the complete opposite of my usual life in London, which is jam-packed with travel, concerts and constantly meeting new people. South Tyrol is the perfect antidote to all that.

Where are your favourite places to spend time and recharge when you’re in Brixen?

I love hiking from Schalders/Scaleres to the Schrüttenseen lakes. I also make sure that I visit the Radlsee lake and the Plose mountain whenever I’m here.

Do you feel equally at home in South Tyrol as in London?

That’s a tricky question, which I often ask myself. I’ve now spent more years living in London than I did in South Tyrol. I was convinced that I’d feel more like a Brit by this point. I know the city and its culture, and the vast majority of my social circle are there. But I still feel a strong connection to Brixen and South Tyrol. It’s where I grew up and first laid down roots, and I feel at home here. I feel at home in London too, but it’s different.

Does music feel like home too?

Yes. The music that I write is heavily influenced by traditional Tyrolean music. It seems to find its way into my music whether I mean for it to or not. I rarely listened to traditional folk music when I was young and I know very little about

the genre. Yet I end up writing a lot of strong melodies where I can hear the sounds of Tyrol coming through.

What music makes you think of South Tyrol? And how about London?

I associate South Tyrol with very simple melodies like the old folk songs that our grandma used to sing to us. Songs like Kein schöner Land in dieser Zeit (No Country More Beautiful in this Time). London is the complete opposite. The city is a melting pot of cultures and people who all bring their own unique styles and genres to the table – everything from improvisations and classical pieces to African and Brazilian beats. London-based artists often mix these sounds together, which is something I like to do too. I take nuggets of inspiration from here, there and everywhere.

You’ve already performed at Dekadenz in Brixen several times, most recently with your latest album, Skyllumina. Does jazz appeal to audiences in your hometown as much as folk music?

Yes, it does actually. I would say that jazz is just as popular in Brixen as it is in the rest of the world. And by that, I mean that a small proportion of the population listen to it. It’s not exactly pop music! But Dekadenz and the South Tyrol Jazz Festival have undoubtedly raised its profile considerably. The festival organisers put together a fantastic programme every year, which always attracts a lot of people.

While composing, Ruth Goller sometimes hears “the sounds of Tyrol coming through” in her work. When she’s back home in South Tyrol, she loves hiking to the Schrüttenseen lakes in Schalders.

+ Tucked away in old stone walls on the winding, narrow streets of Brixen’s oldest district of Stufels/Stufles, the Anreiterkeller cellar cabaret theatre is immensely popular with theatre and jazz lovers alike. Founded by the Dekadenz Group in 1980 as an alternative cultural venue, this charming spot is loved by locals for its tiny stage and small tables with very little legroom. But what it lacks in size, it more than makes up for in atmosphere.

dekadenz.it

+ Every summer, hundreds of well-known jazz artists and upand-coming musicians are invited to play at the South Tyrol Jazz Festival, which has been running since 1982. Spread over ten days, the festival is held at an eclectic array of venues across South Tyrol, ranging from concert halls and bars to historic streets and squares, monasteries, factory buildings, and even mountain summits, lakes, rock faces and pastureland. Of course, there is also plenty of food and drink on offer to accompany the music.

suedtiroljazzfestival.com

+ Many locals still call this iconic bar and café in the centre of Brixen’s old town by its previous name Jazzkeller. The lively venue has stayed true to its musical roots and regularly hosts intimate concerts featuring local singer-songwriters and poppier artists as well as the jazz and blues it was originally known for. The menu includes an impressive number of craft beers from South Tyrol, Italy, Belgium and Germany, which are a particularly refreshing treat when enjoyed in 3fiori’s cool courtyard with its ivy-covered walls during the heat of summer.

3fiori.com

Founded by Blessed Hartmann of Brixen in 1142, the Abbey of the Augustinian Canons of Neustift is one of the largest abbey complexes in Tyrol and looks back on 900 years of history. To this day, it remains a vibrant religious and cultural centre with a Baroque church and magnificent library, as well as a school boarding house, an education and conference centre, and a winery

Built like a fortress

Since around 1200, the entrance to the abbey has been guarded by a round two-storey chapel. Known as the Engelsburg or Castle of the Holy Angel, the chapel is one of the most important Romanesque buildings in Tyrol. It was named after its counterpart in Rome and built as a loose imitation of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. The crenellations and arrow slits were added in the late 15th century to defend the abbey against a possible attack by the Ottomans.

A piece of the Far East

In 2021, wall paintings dating from 1775 to 1780 were uncovered under seven layers of plaster in the anteroom to the library hall. The previously undiscovered paintings feature exotic birds and everyday scenes inspired by China. They show how the Rococo era’s fascination with the Far East also left its mark on Neustift Abbey. A similar style of artwork can be found in the court art commissioned by Empress Maria Theresa at the Hofburg Palace in Innsbruck.

A treasure trove of books and parchments

The abbey is home to almost 100,000 books. 20,000 of them can be found in the Rococo library hall, which extends across two floors with shelves of books reaching right up to the partially gilded stucco ceiling. Bound in fine calfskin with titles written in gold lettering, the books line the walls beautifully and range from extensive compendiums of herbs to song collections. The smallest book measures just five by five millimetres and presents the Lord’s Prayer in seven languages. The library’s oldest book, meanwhile, is a handwritten copy of the Dialogues by Pope Gregory the Great, which dates from the 10th century, making it older than the abbey itself..

Baroque splendour

In the mid-18th century, the abbey church was transformed into the impressive light-flooded, colourful sacred space you see today. Its style is typical of the southern German Late Baroque era. The stucco work, which features numerous rose-coloured angels, is by Anton Gigl from Wessobrunn and the frescoes are by Matthäus Günther from Augsburg. The building itself, together with its Romanesque bell tower and three-aisled nave, was built around 1200, while the Late Gothic choir dates from the late 15th century.

A centre of cultural history and research

Visits to the abbey museum start at the refurbished coach house and take you on a journey through the abbey’s 900-year history. The museum includes exhibits on the abbey’s works of art, books and scientific instruments from the Middle Ages and early modern period. It also gives an insight into the intensive research being conducted behind the scenes, as many pieces in the abbey’s extensive collections have yet to be fully examined.

A winery steeped in history

Wine has been produced on the land around Neustift Abbey ever since the abbey was first founded almost 900 years ago, making the site home to one of the oldest active wineries in the world. For centuries, the wine was only produced for the abbey’s own use, but today it is sold worldwide.

+ Tip: A deluxe guided tour provides a unique opportunity to see some of the rooms that are usually closed to the public, such as the prelate gallery. The tour ends with a wine and cheese tasting .

kloster-neustift.it

Drink responsibly!

If you think South Tyrol is only for wine lovers, think again! A new generation of master beer brewers are making a name for themselves with their very own locally brewed creations. We visit three breweries to find out more

instincts.

Who would think that an area known primarily for its wine would have so many craft beers?

Thomas Lanz

In an attempt to establish a common quality standard that underpins all their creative efforts, the members of the association of South Tyrolean craft brewers have agreed to each make at least one beer from grains exclusively from the region.

Sometimes you have to look twice to see what’s right in front of you. That’s something Thomas Lanz from the Putzer hotel and restaurant in Schabs/Sciaves knows only too well. “Some guests ask us if we serve beer,” he says, grinning as he points towards the floor-to-ceiling windows by the restaurant’s entrance. Through them, the neighbouring on-site brewery and its brewing copper, lauter tun, and fermentation and storage tanks glisten brightly. It’s hard to miss the brewery when ordering a coffee or aperitif at the Putzer’s bar. And yet, it’s no surprise that a few guests overlook it at first glance. After all, South Tyrol is known primarily for its wine, not its craft beer. While Sylvaner, Kerner and Vernatsch are household names, Alma, Treibstoff and Birmehl are often only familiar to people involved in South Tyrol’s current beer boom.

Thomas Lanz, co-owner of the ❶ Viertel Bier brewery in Schabs, is one of them. As are Alexander Stolz from the ❷ Hubenbauer in Vahrn/Varna and Norbert Andergassen from the ❸ Gassl Bräu in Klausen/Chiusa. The trio are among 15 craft beer brewers in South Tyrol with a passion for reviving the artisan tradition of beer-making. They have formed an association of South Tyrolean craft brewers committed to making natural beer without using filtration or pasteurisation. While industrially produced beer

is distributed in huge quantities, craft beer is mainly sold directly where it is brewed so comes fresh from the tank like in times gone by.

Back in the late 19th century, beer was gaining popularity in South Tyrol, and the area was home to almost 30 large breweries all vying for customers. But then the First World War broke out, borders were redrawn, and in 1919 South Tyrol became part of Italy. Ingredients and materials previously imported from north of the Brenner Pass, like grain, hops and copper for brewing vessels, became difficult to get hold of. One brewery after another closed its doors. Only the large Forst brewery in Algund/Lagundo survived, soon gaining a monopoly on beer in South Tyrol.

It wasn’t until 1995 that the tide began to turn. More businesses began applying for brewing licences again and now brewers found that being part of Italy actually worked to their advantage. As Norbert Andergassen from the Gassl Bräu explains, “Unlike Germany, Italy doesn’t have a beer purity law, so there are no limits to our imagination.”

Norbert was one of the first officially certified beer sommeliers in Italy. Today, he works hand in hand with his brewer Timo Puntaier to conjure up all sorts of inventive creations. Besides the traditional malt, water, hops and yeast, the pair add ingredients like basil and chestnut flour to their beer. Most recently, they’ve started using pear flour. Made from dried, finely ground pears, this flour was used

for many years as a substitute for sugar, which was unaffordable in poor farming communities. Large quantities of this natural sweetener were once made in Verdings/Verdignes near Klausen. Today, this village has revived the tradition and celebrates this humble local ingredient every year with a festival dedicated to food and beer flavoured with pear flour. The beer is brewed with a generous helping of pear purée because, as Norbert explains, “pear flour on its own doesn’t create a strong enough flavour”.

The idea to make unusual varieties of beer actually came from Norbert’s wife, Helga. “She loves trying new things,” he explains. All this thinking outside the box is certainly paying off. “Before, guests came in and simply ordered a beer. But today, they ask us about all the varieties we have.”

Sadly, it’s too early in the day for us to sample our first beer, so a cappuccino will have to do. Despite the time, we can already hear a rumbling coming from the Gassl Bräu’s copper brewing vessels, which are housed directly in the dining area itself. Since opening their restaurant in the heart of Klausen’s medieval old town almost 20 years ago, the Ander-

gassens have extended it considerably. In fact, the site where the kitchen now stands was once a small guesthouse with a skittle alley. Today, the fermentation and storage tanks are directly below the kitchen. A narrow channel of water known as a Wiere runs straight through the bar area and is covered by a glass screen. “This water was used by the tanners and joiners who once worked along our lane,” explains Norbert. He doesn’t use this water for brewing, however. Instead, he uses spring water from Latzfons/Lazfons, a village high above Klausen due to it being “very soft and not needing any treatment”.

Water may be the most inconspicuous ingredient in beer, but it has always had a profound impact on the drink’s characteristics. Dark beers were traditionally brewed in places where hard water with a high mineral content was available. The undesirable sharp, bitter taste created by these minerals could be masked using dark roasted malt, which has a strong natural flavour. Pale beer was therefore best made using soft water. Today, minerals can be removed from or added to the water as required, meaning

Brewed from South Tyrolean barley and rye, it bears the South Tyrolean seal of quality. Has hints of elderberry, lychee and lemon balm and is ideal as an aperitif or an accompaniment to light appetisers.

hubenbauer.com

When Alexander Stolz (right) and Gregor Wohlgemuth from the Hubenbauer brewery in Vahrn started out in 2014, they were complete novices. They bought themselves two books and a 250-litre vessel, which they promptly managed to warp on their first brewing attempt after applying too much heat and pressure. Today, they are experts and produce 100,000 litres a year.

that a beer’s qualities no longer depend on the local water’s composition. Despite this or perhaps because of it, Alexander Stolz from the Hubenbauer in Vahrn believes that a beer’s regional character should be preserved. His brewery is located on a narrow road in an old farmhouse dating back to 1197. The word Hofbrauerei (farm brewery) is displayed proudly on its stone walls. This name can only be used by breweries that produce at least half of the ingredients used in their beer themselves. At the Hubenbauer, this figure stands at over 70 percent. “We are the only large agricultural brewery in South Tyrol and grow our own grains, fruit and vegetables as well as rear cattle,” says Alexander. “We smoke our malted barley alongside our sausages.”

Alexander took over the farm from his father in 2014. He hadn’t initially planned to add a brewery. “I wasn’t a huge fan of beer,” he admits. “But my friend Gregor was.” Gregor Wohlgemuth’s passion for beer is written all over his face. His eyes light up as he explains how he persuaded Alexander to give brewing a go. “Alex got hold of a 250-litre vessel and I bought two books on how to brew beer,” says Gregor, who is originally from Meran/Merano.

The pair wanted to brew a top-fermented beer that was the complete opposite of the pale beer traditionally drunk in South Tyrol. Their first attempt failed miserably when the brewing vessel warped under the heat and pressure. But they kept trying and their efforts eventually paid off. The two self-taught brewers became beer connoisseurs and their initial 250 litres turned into an annual volume of 100,000 litres.

As we chat to Alexander and Gregor around a table that they regularly use to hold beer tastings, they seem so relaxed that you might think their vision became a reality all on its own. In truth, it took umpteen hours of renovation work and hundreds of thousands of euros of investment. Today, their brewery is housed in the Hubenbauer’s old barn, which just a few years ago was still filled with tractors

“We smoke our malted barley alongside our sausages.”

members of

make natural beer in small quantities without using filtration or pasteurisation. The

in each

or beer garden.

and hay. Through the large windows, we catch a glimpse of Vahrn’s cemetery, which sits on the other side of the barn’s walls. The church is also a stone’s throw away. It’s certainly an unusual setting for a brewery.

That said, a little divine intervention has always been welcomed. There’s even an old German saying that goes “Hopfen und Malz – Gott erhalt’s” (“God save hops and malt”). Today’s generation of master brewers also rely on courage, a love of experimenting and a healthy dose of naivety. Could these shared characteristics stem from the fact that many young brewers are career changers? Before immersing themselves in brewing, Alexander was a building surveyor and Norbert was a mechanical fitter. Thomas also worked in the construction industry before establishing the Viertel Group with three co-founders. The Group now runs four establishments in and around Brixen, which have been serving Viertel’s very own beer since 2021. Viertel’s beer is brewed by Leonhard Schade, a brewer in his mid-20s from Bavaria in Germany. Despite only recently joining the team, he’s already developed his own creation called the Festbier.

Alexander Stolz →“Before, guests came in and simply ordered a beer. But today, they ask us about all the varieties we have.”

Norbert Andergassen

Basil beer

A light summer beer

Every year in mid-May, the Gassl Bräu rings in the warm weather by tapping this light, refreshing beer. Its distinctive yet well-balanced flavour comes from basil grown in the South Tyrolean mountains and pairs perfectly with summer dishes. gassl-braeu.it

Leonhard swills his beer in a glass, clearly very proud of it. It tastes malty and slightly sweet, and the fizz lingers delightfully on your palate. “It has a beautiful amber colour and is very clear for unfiltered beer,” he points out, explaining that this is due to the time it is left in the tank. This step allows any “unpleasant flavours” – often reminiscent of the smell of nail polish – that may develop during fermentation to be broken down.

Before Leonhard gets to work, he already has a clear picture of a beer’s composition in his mind. Brewing is often a case of trusting your instincts. Or, as Leonhard puts it, finding the right balance. One step where this is important is during lautering, which is the process of filtering the mash (the mixture of malt and water) and separating the liquid from the residual solids. If the liquid is allowed to drain too quickly, valuable sugar may be lost. Alternatively, if the process is too slow, a huge amount of tannins remains, which inhibits fermentation. Once brewed, Leonhard’s Festbier can remain in the tank for 90 days before being bottled. “This is a luxury that industrial breweries can rarely afford,” says Thomas, who is Leonhard’s brewing assistant as well as his boss.

Unlike Germany, Italy doesn’t have a beer purity law, so there are no limits to its brewers’ imaginations. Brewer Timo Puntaier has even mixed ingredients like basil or chestnut flour into the Gassl Bräu’s beer.

Rather than being lone wolves, South Tyrol’s craft beer pioneers work as a team. Even local competitors will help each other out if a brewery runs out of hops or malt or if a pump breaks down. And they all celebrate each other’s successes. “Every good local beer is an advert for us all,” says Gregor.

Just like Viertel Bier, the Hubenbauer has brewed some award-winning beers. Visitors from other parts of Italy are particularly huge fans of the region’s artisan beers. Northern Italy has been a hotspot for Europe’s craft beer boom over the past decade, and the Italian beer market is growing rapidly. South Tyrol’s beer drinkers also love sampling new creations. In an attempt to establish a common quality standard that underpins all their creative efforts, the members of the association of South Tyrolean craft brewers have agreed to each make at least one beer from grains exclusively from South Tyrol. In doing so, they are promoting the use of regional ingredients, strengthening their ties with South Tyrolean farmers and opening up new local supply chains. “Ultimately, people don’t only drink beer for its taste, but because they have an emotional connection to it,” says Leonhard. Emotions are created by experiences. And experiences make history. By giving visibility to a longstanding tradition and bringing exciting new flavours to the table, that’s exactly what South Tyrol’s young master brewers are doing.

Date: 2nd century AD

Size: 18 x 19 cm, 7.4 cm thick

Material: reddish clay

Travel back to Roman times and imagine you’re watching a brickmaker hard at work. In the praefurnium, the kiln’s furnace, thick pieces of firewood are already ablaze, and soon the combustion chamber will reach the required temperature of 700 to 1,000 degrees Celsius. Next to the kiln, reddish clay bricks are neatly lined up, waiting to be fired. The clay has already been cleaned with water and mixed with sand before being shaped into square slabs in a wooden mould.

Before being fired, the bricks are left out to dry until they have a leathery consistency. As you watch brickmaker Secundio pick one up, they are still wet and soft. Hesitantly at first, he uses a fingertip to scratch letters into the clay: an S, an R and a P in capitals using the Roman alphabet. Then he gradually ventures to write his name. On the far left, he inscribes a spidery S and then, on the far right, a lower-case o. It’s as if he’s trying to work out how much space he’ll need. Then he has a go at forming the syllable Se followed by a C, a D and an R. He finally feels ready. Now he writes Secundio at the very top of the brick, applying much more pressure given his new-found confidence.

The fact that our mysterious writer only inscribed a single name suggests that he was a slave. The lettering he used has led historians to believe that he was practising his writing in the 2nd century AD. At this time, a large Roman estate stood on the site where the brick was found – the Plunacker in Villanders/Villandro – and Secundio likely worked in its brickyard. A century earlier, Emperor Augustus had declared the area part of the newly formed Roman province of Raetia.

Why are experts so sure that the inscriptions are writing exercises? The order in which they were made (letters, syllables and finally whole words) matches the method described by Roman educator Quintilian for teaching writing in Roman schools. At the end, Secundio scratched two words starting with “A” into the brick, which was almost dry by that point: aurum meaning “gold”. And agnos meaning “lamb”.

+ In 1979, traces of human life spanning over 7,000 years were uncovered on the Plunacker in Villanders, a sun-drenched slope at 880 metres above sea level. The discoveries included evidence of Mesolithic hunters, the first farming communities from the Neolithic period and early places of worship from the Copper Age, Bronze Age and Iron Age. The archaeological site is one of the most important for this period of time in the Alps. The best-preserved finds come from a Roman estate (dating from the 1st to 3rd centuries AD) and include evidence of livestock and arable farming, workshops and brick kilns. The site’s Archeoparc displays finds and the remains of buildings from all these periods, allowing you to walk in your ancestors’ footsteps.

archeo.bergwerk.it

Interview — BETTINA GARTNER

Interview — BETTINA GARTNER

We meet three inspiring people – a mountain and ski guide, a ski lift expert and lead mountain rescuer, and a mountain skills trainer – who all share a passion for scaling summits and for keeping people safe in the mountains. Read on to find out about their fascinating work and lives, moments of joy and misfortune, and the wonders they see in nature

trustworthy one

As a child, I was afraid of heights. I only had to look down from a balcony, and everything would start spinning. It wasn’t great for a boy like me who was desperate to get out into the mountains. I used to spend my summers watching over goats on a mountain pasture. They clambered up everything, and I soon realised that I’d need to overcome my fear if I wanted to keep up with them. So I started climbing every boulder, wall and rooftop that I could and forced myself to look down. And then one day, the spinning stopped.

I’ve still got a slight fear or rather a healthy respect for heights, but that’s a good thing. It’s probably stopped me from being too reckless and cocky. When I was 15, I started climbing on my local mountain, the Tribulaun, which stands at 3,096 metres above sea level. I was also a member of the Alpine association and mountain rescue service at the time and was keen to learn as much as I could about how to stay safe.

After finishing school, I moved to England and spent 12 years living there. I wanted to learn English because we hadn’t had the chance at school. While I was there, I began working as an outdoor activities instructor – and I continued this line of work when I returned to South Tyrol. My job was to teach young people and adults how to work as a team and how to trust and rely on each other. But it also taught me to trust in my own skills.

When I wasn’t working, I started doing some ice and rock climbing (with and without a rope) in the UK, France, Switzerland and South Tyrol. Wherever you are, preparation is key to a successful climb. It’s imperative that you check the weather, memorise the

trickiest sections of the route and pack the right equipment. And by that, I don’t just mean a drink and an energy bar, but also a compass, map, first-aid kit, bivouac bag and survival blanket – everything you might need in the event of an emergency.

Luckily, I’ve only ever been caught up in one minor mishap, which happened while I was climbing with a friend from England. We were scaling an overhang on a 1,000-metre-high ice wall in the Mont Blanc region when his wallet suddenly flew out of the side pocket of his wind jacket. It held everything, from his ID and plane tickets to his traveller’s cheques. We ended up having to spend the night on the glacier and were only able to return to the foot of the ice wall two days later. Amazingly though, we managed to find most of his things. What a stroke of luck!

When I returned to South Tyrol in 1989, I embarked on two different courses. I studied philosophy, education and psychology in Innsbruck, Austria, before going on to work as a primary school teacher of integration and English. And at the same time, I trained to become a mountain guide. In the late 1990s, I became one of the first to offer snowshoe walking tours, and I’m still doing it to this day. I recently led a group of visitors from Sicily, and they said that they had never seen so much snow in their lives. One member of the group – a grown man – was as excited as a child. What more could you want?

I retired from teaching three years ago and can now dedicate myself fully to my work as a mountain guide. I have the freedom to explore our wonderful natural surroundings whenever I want and love sharing this experience with visitors from around the world.

As a young boy growing up in a quiet valley in the north of South Tyrol, Max Röck had a fear of heights. Today, aged 64, he works as a mountain and ski guide and has been helping visitors safely navigate the mountains near his home for almost 30 years.

On first impressions, Monica Borsatto doesn’t seem like the type of person to instil fear in others. She comes across as quiet and down to earth. And yet, as she tells us with visible amusement, she gave several men “quite a shock” when three years ago she was appointed the Brixen team leader for Italy’s national mountain rescue service CAI. A woman had never held this position in South Tyrol before.

As well as blazing a trail for women through her voluntary work as a mountain rescuer, Monica is accustomed to usually being the only woman on the management team in her job as an environmental engineer. But she brushes this off with a wry smile and a shrug of the shoulders. “In the technical world, objective results are what count,” she says. “Less time is spent thinking about these things than in other lines of work.”

Despite her Veneto roots, Monica appears to have no trouble fitting into life in South Tyrol. She speaks so naturally when she talks of “we South Tyroleans”, it’s as if she has always been here. She feels completely at home in her beloved mountains and heads outdoors and up the rocky summits every chance she gets. Her place of work varies depending on which hat she’s wearing. In her role as a mountain rescuer, she’s based at the large civil defence centre in Brixen, which is shared by several emergency services.

All rescue missions begin from here and there’s a helicopter landing site right next to the building. However, she spends most of her working hours in her office, which is surrounded by historic buildings in Brixen’s old town. The jackets in her office’s cloakroom hang on ropes and carabiners, a pair of wooden skis from the 1960s stands in one corner, and the seat from a chairlift dangles from the ceiling in the middle of the room. Monica acquired the seat when the lift was decommissioned a few years ago, and today it serves as a decorative reminder of her position as one of 100 engineers in Italy appointed as directors of lift operations for the country’s ski resorts. In this role, she oversees the operation of eight lifts in Arabba/ Marmolada by managing the technical inspections, maintenance, servicing and any incidents or downtime.

As a director of lift operations and lead mountain rescuer, Monica holds a lot of responsibility for her teams. She also plays an important role in shaping the landscape of the ski resorts where she works. As an environmental engineer, she specialises in planning mountain lifts and ski slopes. She even designed the men’s downhill ski slope for the World Ski Championships in Cortina in 2021. Dropping 805 metres in height over a length of 2,740 metres and with a maximum gradient of 62 degrees, the dizzying slope was named “Vertigine”, which means vertigo. In true Monica style, it’s pretty frightening!

Born in the Italian region of Veneto but now living in Brixen/Bressanone, 51-year-old Monica Borsatto is a pioneer – not because she was the first to conquer any summits, but because she was the first woman in South Tyrol to become a lead mountain rescuer. And if that wasn’t enough, she is also an environmental engineer and director of ski lift operations.

Matthias Hofer always keeps a shovel in his rucksack. Here he is using it to dig out a piece of snow to check its structure and condition.

Matthias examines the snow crystals using a hand lens. Whether they are big or small, angular or round gives clues as to the state of the snow and how stable the snow pack is.

Are the mountains more dangerous in summer or winter?

In winter because of the risk of avalanches. Saying that, many avalanches can be avoided as long as people pay attention to two fundamental factors.

Which are?

The avalanche risk level and the gradient of the slope. The higher the risk level, the more important it is to stick to less steep terrain. For example, at avalanche risk level 2, you should avoid areas within a 20-metre radius where the terrain is steeper than 40 degrees. At avalanche risk level 3, you must keep to slopes with a gradient of 35 degrees or less. And at avalanche risk level 4, this threshold drops to 30 degrees, and you also need to consider where any potential avalanche debris could fall. It’s also important to pay attention to any hazards mentioned in the avalanche report, such as old snow, and approach these with particular care.

You make it sound easy.

It is. Statistics from South Tyrol clearly demonstrate that these rules were not observed in 90 percent of avalanche incidents. The people involved were in areas that were too steep given the avalanche risk level. Around two thirds of all accidents happen at avalanche risk level 3 – for exactly this reason!

Do I need an expert guide to venture off-piste?

Not necessarily. You can head out on your own, as long as you stick to what you know you can do safely. As Austrian alpinist Paul Preuss once put it, “Your ability determines what you can do.”

What if I’m feeling less confident?

There are plenty of courses on offer from mountain guides or your local Alpine association. Or you could join someone more experienced and qualified and pick up tips from them. As the saying goes, the greatest masters are those who never stop learning.

How did you start developing your understanding of the mountains?

As a child, I worked with my uncle on the mountain pasture in Villanders, and those experiences sparked my fascination with nature. For years, my goal was to become a mountain guide, but it’s not an easy career to pursue when you’re young. You have to master many different routes and difficulty levels across all the disciplines of high-altitude hiking, ski touring and climbing. That takes time, which is why I initially had to earn a living as a surveyor. I eventually became a mountain guide in 2010. But it was only when I was

offered a job as a training manager for the South Tyrolean mountain rescue service four years later that I was finally able to turn my love of conquering the mountains into a career.

What must both pros and amateurs always do before venturing into the mountains? They need to plan their route carefully by considering several factors. What’s the weather like? What does the avalanche report say? And how many people are in my group? If you’re heading out with a guide, six people is the ideal number for ski touring and around ten people for snowshoeing. But no matter how well you’ve planned everything, you should always expect the worst.

How do you mean?

You should always mentally prepare yourself for extreme situations. That means treating mountain sports no differently to how you treat an activity like driving. What would you do if a motorbike overtook you but then crashed right in front of you around the next bend? If you imagine a situation playing out in your mind, it’s less shocking if it actually happens. This doesn’t stop you from making mistakes, but it can be incredibly helpful.

Matthias Hofer, 43, from Villanders/Villandro changed careers to become a ski and mountain guide 13 years ago. Today, he trains rescuers, ski instructors and hiking guides, gives talks to share his knowledge and provides expert assistance following accidents in the mountains.

You sound like you’re talking from personal experience...

I once took two customers on a ski tour in Trentino. They were both highly experienced but still wanted me to guide them. We were climbing a steep gully and were just ten metres from the top when I suddenly had a feeling that we were in danger and needed to turn back. I lowered the customers down a steep section, but before I could descend it myself, I was carried away by an avalanche.

Can you remember what ran through your mind in that moment?

I thought to myself: “It’s May, the season is coming to an end, and how typical that today of all days is the first time all winter that I don’t have my ABS avalanche airbag with me.”

You didn’t think about your family or about dying?

No. The size of the avalanche and the flat ground beneath the gully meant that I knew straightaway that nothing too serious would happen. The next thing I thought was that I needed to get rid of my ski poles. If your hands get stuck in the straps, the poles will just pull you downwards during an avalanche. I spotted a good place to discard my poles, where I could pick them up again later. And that’s exactly what I did because, thankfully, I was only buried up to my waist.

Were you afraid afterwards?