9 minute read

Impact of dra regulations of Geoscience Act on exploration companies

GEOSCIENCE ACT Could draft regulations pose a threat to exploration companies in SA?

By AngloGold Ashanti senior specialist: legal Aviona Mabaso

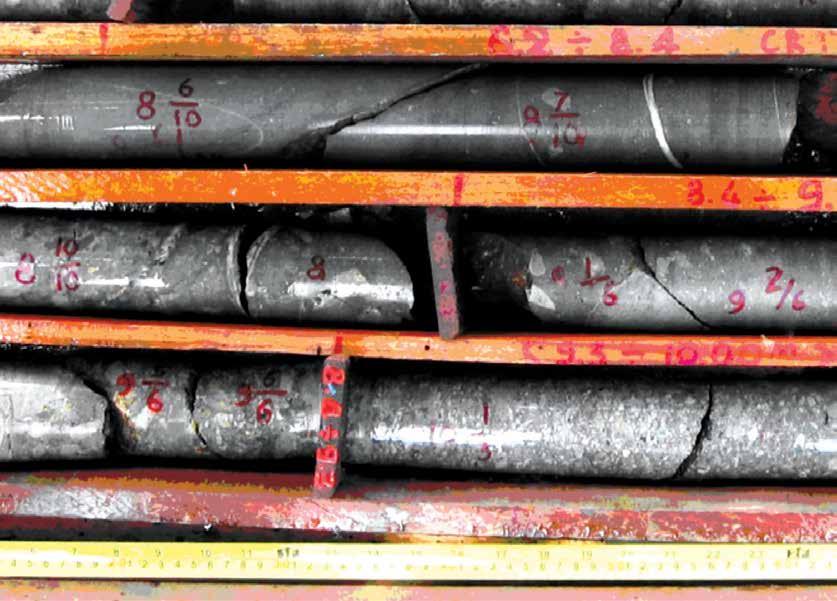

Mining is a big, expensive business. To actually take a greenfields project from nothing to bankable feasibility and all the way to actual mining is an expensive exercise. It’s funded by investors who have the appetite for such a risk or gamble that millions of dollars can be sunk into the ground to find nothing. It is therefore no surprise that information on a mineral resource is closely guarded intellectual property of the explorers. In South Africa the Geoscience Act makes provision for the Council for Geoscience to serve as the national custodian for geotechnical, prospecting and all other geoscientific information relating to the earth, the marine environment and geomagnetic space, all of which must be lodged with the council. The Mineral and Petroleum Resources

Development Act (MPRDA) also makes provision for the lodging of data with the council. The Council for Geoscience’s objectives are to promote the search and exploitation of minerals in the country, undertake research in the field of geoscience, act as a national advisory on geohazards to infrastructure and development and geoenvironmental pollution brought about by mineral exploitation and other actives, and provide specialised geoscientific services. The council is represented by a board that consists of a chairperson and o icials appointed by the mineral resources minister from the departments of water and sanitation, rural development and land reform, as well as human settlements,

Aviona Mabaso.

The dra regulations “ require extensive disclosure of prospecting and mining information.“ – Mabaso

science and technology, Treasury, and four people with appropriate experience or knowledge.

Although the Geoscience Act specifically prohibits the council from undertaking any mining development for itself or any research on behalf of any private institution that would favour another in acquiring an asset, the holders of prospecting rights are required to submit progress reports and data relating to their prospecting operations to the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy (DMRE) and the Council for Geoscience.

No person may dispose of or destroy any record, borehole core data or core-log data except in accordance with the direction of the DMRE in consultation with the council. These records are not generally accessible to the public.

Recently the mineral resources and energy minister published dra regulations for public comment that would require extensive disclosure of prospecting and mining information by rights holders and non-right holders.

If enacted, these dra regulations would require all onshore and o shore prospecting geoscience data and info (e.g. technical reports, progress reports and prospecting reports) on reconnaissance and prospecting to be lodged annually by the right holder from date of grant or within 30 days of it lapsing.

There is a regulation titled “lodgment of all onshore and o shore geoscience data and information, not related to reconnaissance and prospecting”. Although it was not specified, I believe this provision was supposed to apply mutatis mutandis in respect of mining rights and mining permits.

All onshore and o shore geoscience data and info collected by any non-right holder would need to be lodged as well. Non-rights holders include South African and foreign governments, and private and public entities. Any foreign entity that undertakes geosciences research would need to inform the council within 60 days, and submit a report of their research within an agreed time

frame of completion of research. It doesn’t mention by when South African non-rights holder entities need to submit geoscience data and information it collected.

All historical onshore and o shore prospecting and reconnaissance geoscience data (e.g. technical reports, progress reports and prospecting reports) that is more than 15 years old would need to be lodged within 18 months of the commencement of the dra regulations. This obligation also seems to apply to any person (private/public, including foreign governments and entities).

The MPRDA already has some disclosure obligations with respect to prospecting. Firstly, the holder of a prospecting right or reconnaissance permission is required to keep and submit proper records of their operations, submit annual progress reports and data, and submit a further report on expiry of the right, to the regional manager of the DMRE. That manager must submit this to the council.

Secondly, no closure certificate may be issued unless the Council for Geoscience has confirmed in writing that complete and correct prospecting reports in terms of s21 of the MPRDA have been submitted, and complete and correct borehole core data or core-log data that the council deems relevant has been lodged.

In the case of a (mining) right or permit holder, the complete and correct surface and relevant underground geological plans must have been lodged.

Lastly, s30(5) of the MPRDA requires all information submitted to the Council for Geoscience (by the holder) in terms of s21 of the MPRDA to be kept confidential until such right prospecting right/reconnaissance permission has lapsed, is cancelled, or terminated, or the area they relate to has been abandoned or relinquished.

S30(3) of the MPRDA entitles holders and applicants to specify which information may be disclosed and what must be treated as confidential and remain undisclosed.

Although the council may take information into custody except where another law imposes a restriction on the publication or display of such information, the way that the current dra regulation is phrased, all geoscience data and information may be made accessible and disseminated and made available on written request (of anyone). This includes information submitted in terms of the Geoscience Act as well as the MPRDA.

This conflicts with s30 of the MPRDA and is ultra vires section 6(2) of the Geoscience Act. The regulations contain no secrecy or confidentiality provision regarding documents, information, and particulars so provided. This would be a huge hindrance to trying to sell exploration projects. Keep in mind that the Geoscience Act already allows the council to produce and sell reports, maps, computer programs and other intellectual property which it generates from its research.

Although nothing stops owners of information from monetising and selling the data, they can’t warrant/guarantee that the info is and will remain confidential/ secret. The Council of Geoscience would end up being the biggest competitor of other explorers. This could deter investors from investing in exploration companies in South Africa. A er all, investors of exploration companies are investing to gather data. ■

Exploration companies invest to gather data. Prospecting geoscience data.

Mineral resource information is closely guarded intellectual property of the explorers. “ “ – Mabaso

COMMODITY PRICES

A BUOY FOR SA’S MINING INDUSTRY

The sun is not setting on the mining industry, but if South Africa wants to optimise the benefit, the sector needs to improve its preparation for the opportunity on its way.

South Africa’s mining industry, while able to continue during the COVID-19-induced lockdowns, was still hindered by the disruptions caused with employees contracting the virus or whose members in their communities fell ill.

Compounded by the recent civil unrest in many parts of the country, while mine production wasn’t directly a ected, downstream processes were; and so were the communities who work in the mines.

While the labour-intensive industry is seeking solutions for their current challenges, the market presents growth opportunities.

The most popular mining commodities are no longer gold and diamonds, but rather platinum group metals (PGMs). These commodities have performed very well over the past couple of years.

The prices of metals used in environmentally friendly projects and products are expected to increase as demand increases. This is because of the re-electrification of the world, including renewal energy solutions and electric cars.

With the current chip shortage that is expected to be solved in the next year or two, this will push up the demand for PGMs and other metals. This is due to the pent-up consumer demand as economies are opening up a er COVID and global logistic challenges, from vehicles to white goods and other electronics.

China is increasing its metal stockpiles. This is in anticipation of the upcoming demand.

There is a massive opportunity for South Africa as well as countries in the rest of Africa to meet the expected increase in demand which is expected to continue on an upward trajectory.

Delays in the development of new mining projects in South Africa could place the country in an unenviable position where it may lose out to its competitors on the rest of the continent.

An increase in revenue from higher commodity prices may make some mining companies reconsider their position on investing in new projects. This will also have a positive knock-on e ect to assist in reducing the level of unemployment in the country. The current financial position of most mining companies is stronger. There has been a concerted e ort to reduce debt levels, which could factor into a revisit of new opportunities. There are concerns that the higher commodity prices will not hold and may decline as is customary with all commodity cycles. But for about the next three to five years, the current upward trajectory should remain with bouts of volatility. The mining industry does go through commodity price cycles,

Johann Erasmus where prices do decrease, but historically demand has always bounced back. Executive director at 1nvest Aside from the labour costs, one of the concerns for the industry is accessibility to regular, uninterrupted power supply. The recent allowance of 100MW power production permitted without a generation licence is a positive step forward, and will ease the burden for the industry. Mining companies are also being proactive in their environmental, social and governance responsibilities, especially around people and the environment. Mining historically has a poor reputation when it comes to environmental and social concerns. But it is important to note that especially new mines who have access to © ISTOCK – Wiyada Arunwaikit newer technology are incredibly conscious about the e ect they have on the environment and the communities that support them. Water, especially in a country that has a limited supply, is another concern that the mining industry has. In the industry, using water wisely and safely must be top of the agenda. New technology is allowing the mines to be more water-conscious not just in usage but to protect the resource from contaminations. While some may say it’s a sunset industry, mining in South Africa has the opportunity to grow and flourish, and it remains a large contributor to the country’s GDP. If the sector prepares well and South Africa can become a beneficiation hub in Africa, it will be an instrumental sector in assisting our economy, and place the country on a stronger road to recovery. ■