9 minute read

Borders in Film

Borders in Film Article by Anthony Sennett

American Honey (2016) By December 31st, a nearly innumerable collection of films will be crammed into a memory box. No matter the artistic pedigree, intent, or cultural value, any work from these past ten years will be concretely related to one another. While the age of the superhero will most likely define this era of American cinema in retrospect, a beautiful array of voices were heard outside of the Marvel cinematic universe. Mid-decade, indie audiences witnessed the birth of a boldly deconstructed and raw form of realism from the likes of American Honey (2016), Tangerine (2015), and Heaven Knows What (2014), in tandem with the hyper-stylized revelations of Sorry to Bother You (2018), The Love Witch (2015), Anomalisa (2015), and the good and bad of Nicholas Winding Refn’s neon-soaked world. A renaissance in horror came to fruition due to the likes of Robert Eggers, Jordan Peele, and Ari Aster, and sci-fi reached new heights with Denis Villenueve’s Arrival (2016) and Blade Runner 2049 (2017) and Alex Garland’s Ex Machina (2014) and Annihilation (2018). Reasserting their unyielding talent, David Fincher, Wes Anderson, and Paul Thomas Anderson cemented their status as masters. Along with all this, the heartwarming hug Lady Bird (2017) provided was equalized by the stomach wound inflicted by Suspiria (2018). Although there is an abundance of realized and budding talent within the states, there is no reason to remain within the boundaries of the english language. No matter how great of a selection America boasts, the need for outside perspectives is essential to sustaining a diverse and well-rounded artistic atmosphere.

Advertisement

While the 2000’s were prevalently filled with escapist fantasies of middle earth and wizard kids, there was an emergence of films extraneous to America growing more accessible and popular. From Spirited Away to Pan’s Labyrinth, a more diverse spectrum of voices and styles were beginning to share the spotlight with the likes of James Bond and Tom Cruise playing the character of Tom Cruise. In 2009, on a strip of land along the Mediterranean Sea, director Yorgos Lanthimos introduced the Greek New Wave to the world. Releasing his second feature film Dogtooth, Lanthimos’ style was mundanely surreal, providing an unsettlingly raw lens through which to view the human condition. The following year, he would star in Athina Rachel Tsangari’s Attenberg. As Tsangari stated, “I thought it would be interesting to observe Marina (the main character) the way Attenborough observes his subject, with a kind of scientific tenderness.” This approach is reflected in the opening scene, focusing on an emotionless, uncomfortably prolonged make out session. This audaciously bleak presentation is the defining characteristic that would

Tangerine (2015)

Heaven Knows What (2014) remained constant in her’s and Yorgos’s artistic evolutions. While the collaborative nature of their relationship brought out the best in each other, their dependency on one another was also out of necessity. Living in a country continuously plunging deeper into economic disaster, these artists’ micro-budgeted self expressions are stifled by the very place that inspires them. With family being at the forefront of societal importance in Greece, Lanthimos and Tsangari’s stories subvert the expectations their homeland had set for so long. While Athina pledged to stay and explore said disastrous state through her art further, Yorgos moved away from the wreckage, importing their unorthodox style for an American audience, releasing one more Greek-language film Alps (2011) before his first English-language feature The Lobster (2015). With a larger budget and star-appeal, the indie hit breathed even more fresh air into an increasingly multifarious market, with a writer proclaiming “it opens [one’s] eyes to a new way of storytelling.”

While the Greek New Wave honed a singular style through which citizens of a country express themselves, the opposite is true of France, a powerhouse of innovate and distinctive cinema home to the infamously provocative Gaspar Noé. His two releases this decade withheld nothing, with the ultra-erotic Love (2015) and nightmarish Climax (2019) pushing boundaries no other director or region had previously attempted. Julia Ducournau’s Raw (2016) provides a graphic tale of a vegetarian tasting meat for the first time, spawning a need for human flesh. Her vision is so unabashedly unique it transcends any horror or coming of age trope previously set in place, garnering controversy for its truly unfiltered

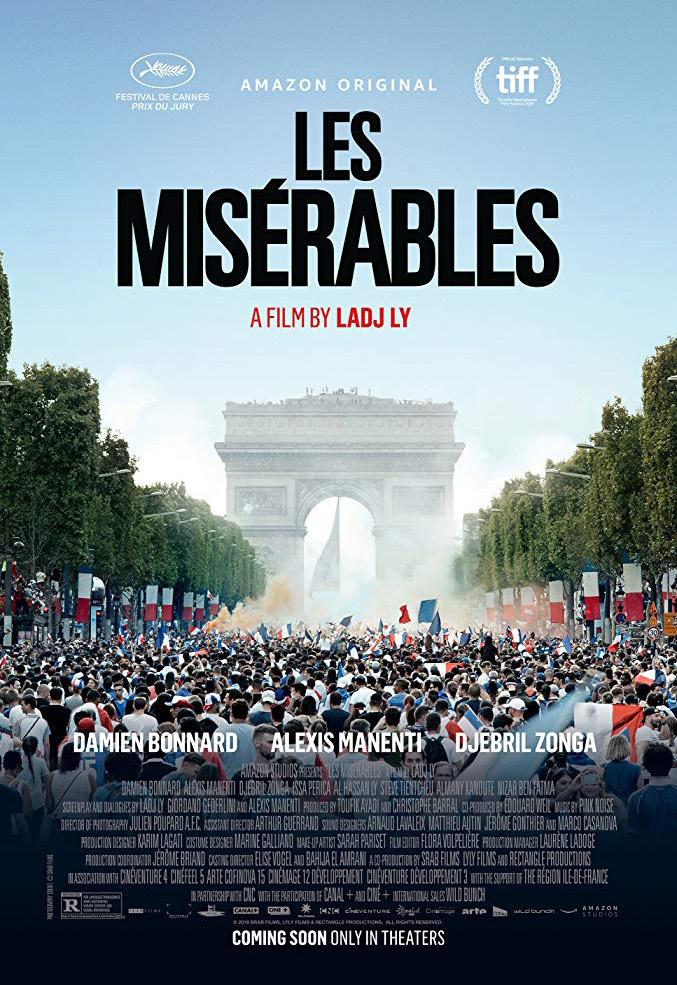

presentation. This level of artistic expression is not new to the country, as proven by its rich catalog of work from Jean Cocteau to Agnes Varda. Using his countries’ artistic past to frame the present, Ladj Ly’s Les Miserables (2019) provides an unflinching look at police brutality in impoverished areas around Paris. Using child actors from the very slum Ladj himself had lived in, this autobiographical directorial debut explodes with urgency, even being screened for the president amidst widespread riots due to the same issues. On the other end of the spectrum, films such as Oliver Assayas’s Clouds of Sils Maria (2014) and Celine Sciamma’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire (2019) present themselves with beautiful ambiguity, grounded in reality yet elevated by their stunning presentations and subtle surrealist imagery. French cinema shows no sign of slowing down, and a vast horizon of impossibly eclectic and uncharted art is ready for global

Les Miserables (2019) While France has cemented itself as a center of the arts, every country has a valuable cinematic voice to offer. There is a beautiful quality to films that resonate beyond the borders of their land, yet still tell a story uncompromisingly specific to the region they originate from. Stemming from the turmoil of gender politics in Turkey, Deniz Gamze Erguven’s Mustang (2015) highlights the horrible conditions women of all ages endure in her country, rightfully comparing their standard of living to “the middle ages.” Managing to work around the censorships Iran has placed on cinema, Asghar Farhadi’s A Separation (2011) provides another unflinching view of gender relationships and the investigative system in Iran, vividly depicting what is banal to their culture yet so foreign from a modern American perspective. With a narrative comparable to Blue Valentine (2010) and Marriage Story (2019), the complexities of A Separation’s failing marriage are universally understood. Three years later in Iran, however, a film inherently tied to western art surfaced; Ana Lily Amirpour’s A Girl Walk Home Alone at Night. Inspired by old spaghetti westerns and nosferatu, this tale of a lonely vampire subverts the genres it originated out of. The jarring amalgamation of cultures makes it inherently political. As writer Moze Halperin believes, the contrast between the presentation of the female lead being a vulnerable, lonely woman ‘walking alone’ and the fact that this very character is a predator “speaks to America’s strange tendency to read the chador as a symbol of both victimization and threat.” This decade also saw famed Iranian director Abbas Kiarostami’s creating a french-based film with Certified Copy (2010), centering around a discussion on the value of originality yielding beautiful results. While Pawel Pawlikowski’s phenomenal Cold War (2018) could be simplified as a story of undying love, it is an inherently Polish film, grounding itself in the harsh realities of post-war life, with the rhythm of their relationship evolving out of history itself. In 2013, a king of Japanese filmmaking, Hayao Miyazaki, released his most mature film The Wind Rises, a story fueled by the corruption of capitalism using pacifist ideology. By critiquing his countries’ hubristic and damning attitude in World War II, Miyazaki was met with opposition from the political right. Drawing from the modern day insight on poverty in Japan, Hirokazu Kore-eda created an equally honest depiction of the struggles of his culture in Shoplifters (2018). Stating “I don’t portray people or make movies where viewers can easily find hope,” this philosophy gave way to one of the most raw portrayals of the evils of capitalism, a message easily translatable across borders.

In the end, due to the widespread influence of western culture and the domineering presence of American filmmaking, making an english language film has been the most accessible way for artists to create work with universal impact. Sebastian Lelio, Claire Denis, Pablo Larrain, Yorgos Lanthimos, and Denis Villeneuve are a handful of directors who have made their english language debut this decade, spawning their most widely notable films to date. While there is beauty in bringing the expansive

viewpoints and singular voices of foreign directors to the ideology and culture of the United States, there is, thankfully, a larger cultural shift taking place. With the widespread acclaim of both Roma (2018) and Parasite (2019), international art is becoming more accepted and revered by the masses. Both of the films previously mentioned are created by masterful directors after a long run of english-language films. With Roma being helmed by such a renowned artist as Alfonso Cuaron, he took his success and created a Spanish language narrative centered around a soft-spoken live-in maid in Mexico City. The platform he gave this intimately stunning work of art led to Yalitza Aparicio, the film’s star, becoming the first Indigenous American woman to receive an Oscar nomination. Being amongst the best reviewed films of the decade on top of its record breaking screening attendance statistics, the Korean language film Parasite

Roma (2018) further attenuates the shift in artistic consumption. The reason for its success and ability to transcend the barriers inherently restraining its success was put most eloquently by Bong Joon Ho, the director, himself: “I tried to express a sentiment specific to Korean culture, all the responses from different countries were pretty much the same. Essentially, we all live in the same country called capitalism.” Tying in with the same appeal Shoplifters held a year earlier, the desire for truth is as strong as ever. With themes of spirituality explored in Alice Rohrwacher’s Corpus Celeste (2011), Ida (2013), and Uncle Boonmee Recalls his Past Life (2010), these core human interests are not something divided by regions. While it is integral to call for more diversity within the American Hollywood system, we can find representation outside this country as well, with, for example, the LGBTQ+ narratives of Xavier Dolan, Thelma (2017), The Handmaiden (2016), and A Fantastic Woman (2017). While Parasite is far from the first international film to resonate deeply amidst so many different societies, it serves as a beacon of hope for what is to come in the 20’s. With Disney continuing to rapidly reveal itself as a lifeless, cash-grabbing monster, now is a more vital time than ever to bring international directors to the forefront.