Blakey Davis Coltrane

BOP Monk

MParker ulligan

The Rise of Bop

A Journey Through a Jazz Evolution

In the dimly lit corners of Minton's Playhouse in Harlem during the early 1940s, a quiet revolution was brewing. The smoke-filled room, alive with murmured conversations and the clink of glasses, held within it the seeds of a seismic shift in jazz music. The big bands of swing still dominated the airwaves and ballrooms, but for a select few visionaries, the time had come to challenge convention

At the heart of this movement was a tightly-knit group of young musicians who sought to break free from the predictability of swing arrangements. Thelonius Monk, with his angular piano chords, and Kenny Clarke, who revolutionized drumming with his shifting rhythms, were among the first to experiment They found a kindred spirit in the alto saxophonist Charlie "Bird" Parker, whose lightningfast improvisations seemed to channel something otherworldly. Not far behind was trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie, a flamboyant performer whose technical prowess matched his imaginative, complex lines Together, these musicians began to redefine the language of jazz They played with harmonic structures, introducing extended chords and chromatic improvisation. Their rhythms, spurred by Clarke’s innovations on the ride cymbal, created a more dynamic, unpredictable interplay among the instruments At Minton's and Monroe’s Uptown House, the rules of jazz were being rewritten, one after-hour jam session at a time. By the mid-1940s, bebop had taken shape, though it remained an underground phenomenon. The first recordings of this bold new style came with small groups featuring Parker and Gillespie Tracks like "Ko-Ko" and "Salt Peanuts" became emblematic of bebop’s energy and complexity

Gillespie’s big band, though initially a financial gamble, introduced the masses to this art form, with tunes like "A Night in Tunisia" blending bebop with Afro-Cuban influences. Despite its brilliance, bebop faced resistance. Many found the music too challenging, its intricate melodies and breakneck tempos a stark contrast to the accessible swing tunes of the era Yet, for those who listened closely, bebop offered unparalleled freedom and emotional depth. The music became a badge of intellectual sophistication and artistic integrity, embraced by both musicians and an emerging audience of jazz aficionados

Bebop's rise coincided with the emergence of iconic venues that served as incubators for this avant-garde movement. In addition to Minton’s, Birdland opened in 1949, named after Parker himself, becoming the premier destination for bebop performances The Royal Roost and later the Five Spot Cafe also became hotbeds of innovation, where audiences could witness legends like Bud Powell on piano and Max Roach on drums pushing the boundaries of jazz. These players were not merely virtuosos; they were storytellers, weaving narratives through their solos. Powell’s fiery yet lyrical playing gave the piano a new voice, while Roach’s polyrhythms turned drumming into a conversation with the rest of the band Miles Davis, a young trumpeter with a cool demeanor, entered the scene during this period, contributing to Parker’s quintet and developing his own voice that would later shape jazz history.

As the 1950s progressed, bebop evolved into hard bop, a style that infused the complexity of its predecessor with the soulful, bluesy undertones of gospel and R&B Musicians like Horace Silver and Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers became standardbearers for this next phase. Hard bop brought jazz back to its roots, resonating with wider audiences while maintaining its artistic edge.

This period also saw the rise of funky bop, characterized by grooves that were both intricate and infectious. Cannonball Adderley’s "Mercy, Mercy, Mercy" and Lee Morgan’s "The Sidewinder" exemplified this genre, bridging the gap between bebop’s intellectualism and the visceral appeal of danceable rhythms

At the same time, soul jazz emerged, blending bebop’s sophistication with the raw emotional power of rhythm and blues. Organists like Jimmy Smith and saxophonists such as Hank Crawford carved out a niche that brought jazz to nightclubs and jukeboxes across America

By the 1960s, the spirit of experimentation that had birthed bebop led jazz into uncharted territories Latin influences, brought to the fore by musicians like Gillespie and percussionist Chano Pozo, merged seamlessly with bop. Their collaborations introduced a global sensibility to jazz, evident in classics like "Manteca."

What began as a late-night experiment in Harlem reshaped the course of music forever. Bebop, with its relentless drive for self-expression and its embrace of complexity, became the foundation for countless jazz styles that followed Its pioneers, from Monk to Bird, were more than musicians; they were architects of a cultural revolution.

The seeds planted by bebop would also germinate into fusion, as artists like Miles Davis and Herbie Hancock began incorporating electric instruments and rock elements into their music Davis’s "Bitches Brew" and Hancock’s "Chameleon" represented a bold leap forward, yet they carried within them the DNA of bebop’s fearless innovation.

As the final notes of a bebop tune fade, they leave behind a legacy of boundless creativity From the frantic energy of "Ornithology" to the groove-laden pulse of funky bop and the global embrace of fusion, the story of bebop is one of continual reinvention a testament to jazz’s enduring spirit of innovation

Moanin

The Jazz Messengers

(1957)

Released in 1958 on Blue Note Records, Moanin’ is widely regarded as one of the most iconic hard bop albums ever recorded. The record not only solidified Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers as the gold standard of small jazz ensembles but also became a defining statement of the hard bop movement Its infectious grooves, bluesy melodies, and fiery improvisations capture the essence of jazz’s soulful and sophisticated side The title track, composed by pianist Bobby Timmons, became a jazz standard and a gateway for many listeners into the genre Moanin’ exemplifies Blakey’s mission to create music that connected with audiences on a visceral and emotional level while maintaining technical brilliance. It remains one of the most beloved albums in the jazz canon. Moanin’ was recorded on October 30, 1958, at Rudy Van Gelder’s studio in Hackensack, New Jersey

Produced by Alfred Lion for Blue Note, this album showcased one of the greatest iterations of the Jazz Messengers lineup. Each member contributed to the album’s vibrant sound and enduring legacy:

Art Blakey – Drums Blakey’s drumming is the driving force behind the session His dynamic range from thunderous explosions to subtle grooves creates a powerful and propulsive backdrop.

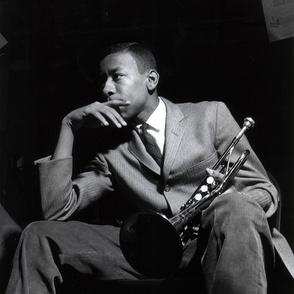

Lee Morgan – Trumpet

At just 20 years old, Morgan’s fiery tone and expressive phrasing are astonishing His solos blend technical precision with blues-drenched emotion

Benny Golson – Tenor Saxophone Golson brings compositional sophistication and a smooth, lyrical style to his improvisations. His contributions as both a performer and a composer elevate the album

Bobby Timmons – Piano Timmons’ gospel-infused playing is the soul of the record His ability to blend complex harmonies with earthy rhythms is evident throughout.

Jymie Merritt – Bass

Merritt’s steady, swinging lines anchor the group, providing a firm foundation for the horn players and Blakey’s powerful drumming

Moanin’ is an essential album not just for hard bop enthusiasts but for anyone exploring jazz It encapsulates everything that makes Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers legendary: fiery energy, deep blues roots, gospel influences, and a balance of technical skill and emotional depth The album is a perfect entry point into the hard bop style and remains a towering achievement in Blakey’s extensive discography. Whether you ’ re a seasoned jazz fan or a newcomer, Moanin’ is an album that demands to be heard

Moanin

The album opens with Bobby Timmons’ legendary title track, an infectious gospel-blues anthem. Timmons’ call-and-response theme is instantly recognizable, and the solos are brimming with personality: Morgan’s exuberant trumpet, Golson’s smooth tenor, and Timmons’ own rollicking piano chorus Blakey’s drumming drives the tune with his signature shuffle groove, creating a perfect mix of soul and swing

Are You Real

A Benny Golson composition, this tune features a more intricate melody and harmonic structure. The interplay between Morgan and Golson is tightly woven, and the solos are both lyrical and fiery. Blakey’s drumming is particularly dynamic, adding depth and energy to the performance

Along Came Betty

Another Golson classic, this track leans into a romantic and cinematic feel, showcasing his gift for crafting lush, melodic ballads. Morgan’s restrained trumpet solo is a highlight, demonstrating his versatility Timmons’ delicate comping and Blakey’s brushwork add to the track’s warm, tender mood

The Drum Thunder Suite

This three-part suite, composed by Golson, places Blakey’s drumming front and center It begins with a dramatic, martial theme before transitioning into a swinging middle section and closing with a percussive finale Blakey’s solos are both explosive and intricate, showing his unparalleled skill as a drummer and storyteller

Blues March

Golson’s military-inspired tune combines a march rhythm with bluesy phrasing, creating a unique and joyful piece. Morgan’s solo is a standout, full of bold phrases and bluesy inflections. Blakey’s drumming evokes a parade, complete with sharp rimshots and a driving cadence

Come Rain or Come Shine

A standard composed by Harold Arlen and Johnny Mercer, this rendition showcases the group ’ s ability to take a familiar tune and make it their own. Golson’s warm tenor saxophone leads with an emotional solo, while Timmons’ piano adds a gospel-tinged backdrop Blakey’s sensitive playing enhances the tune’s understated elegance

The Saxophone Colossus Sonny Rollins

Sonny Rollins, born Theodore Walter Rollins on September 7, 1930, in New York City, is celebrated as one of the most influential and enduring figures in jazz history A tenor saxophonist with an innovative approach and unyielding creativity, his career spans over seven decades, leaving an indelible mark on the genre.

The 1950s were his breakthrough years Albums like Saxophone Colossus (1956) cemented his place among jazz royalty. Tracks like “St Thomas,” inspired by his Caribbean heritage, “Blue 7,” with its complex improvisation, and “Moritat” brought listeners into a world where melody met bold, rhythmic invention. Then there’s The Bridge (1962), recorded after a self-imposed sabbatical During this period, he famously practiced on New York’s Williamsburg Bridge, seeking solace and honing his craft. This album, featuring guitarist Jim Hall, bassist Bob Cranshaw, and drummer Ben Riley, represented not just a return but a reinvention. The interplay on tracks like “Without a Song” was a testament to his never-ending quest for growth. Rollins’ other standout works include Way Out West (1957), where he explored a stripped-down trio format with bassist Ray Brown and drummer Shelly Manne, and Freedom Suite (1958), a powerful statement on civil rights wrapped in musical brilliance

Born and raised in Harlem, a neighborhood alive with cultural and musical energy, Rollins grew up surrounded by the rhythms and sounds of jazz. He picked up the alto saxophone as a young boy, later transitioning to the tenor saxophone, which became his voice. By his late teens, he was performing with seasoned musicians like Babs Gonzales, J.J. Johnson, and Bud Powell. .

Over his career, he played alongside legends Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk, and Max Roach among them. His partnership with Clifford Brown and Max Roach’s quintet is often regarded as a zenith in modern jazz, particularly on albums like Clifford Brown and Max Roach and Plus Four (1956)

But it wasn’t just about the big names. Rollins had a way of elevating any musical context, his improvisational style marked by thematic development and a fearless willingness to explore John Coltrane, Wayne Shorter, and Joshua Redman have all pointed to him as a profound influence, proof of his reach far beyond his contemporaries

Even as trends shifted, he never stopped innovating From the avant-garde explorations of East Broadway Run Down (1966) to the global textures of Road Shows, Vol 1 (2008), his work reflected an insatiable curiosity. Though health issues led him to retire from performing in 2012, he remains a vocal advocate for music and its transformative power

His accolades speak volumes a National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Master, a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award, and countless others But the true legacy lies in the music: the way it swings, soars, and connects. Rollins’ sound is a conversation, a story, a challenge. It’s jazz at its most alive.

JaneDoe

Essentials

25 Mid-Century Bop Albums

Bebop (1940s–early 1950s)

Charlie Parker – Charlie Parker with Strings (1949–1950)

Parker blends bebop with lush orchestral arrangements, redefining the jazz soloist's role

Dizzy Gillespie – Groovin’ High (1945)

A collection of Dizzy’s early bebop sessions that capture the style’s fiery birth

Thelonious Monk – Genius of Modern Music, Vol. 1 (1947–1948)

A pivotal album introducing Monk’s unique compositional and improvisational genius.

Bud Powell – The Amazing Bud Powell, Vol. 1 (1949)

Powell’s virtuosic piano playing was central to the bebop movement.

Fats Navarro – Fats Navarro Featured with the Tadd Dameron Quintet (1948–1949) Navarro’s lyrical trumpet style is on full display, complemented by Dameron’s elegant arrangements

Miles Davis – Birth of the Cool (1950)

Though rooted in bebop, this album launched the "cool jazz" aesthetic, influencing countless artists

Sonny Rollins – Moving Out (1954)

Early Rollins displaying his burgeoning prowess as a tenor saxophonist in the bebop idiom

Sarah Vaughan – Sarah Vaughan (1954)

Featuring Clifford Brown, Vaughan’s album showcases how bebop influenced vocal jazz.

Hard Bop (1950s–1960s)

Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers – Moanin’ (1958)

One of the quintessential hard bop records, blending blues and gospel influences with bebop

Clifford Brown and Max Roach – Clifford Brown and Max Roach (1954)

A masterpiece of hard bop, showcasing Brown’s brilliance and Roach’s rhythmic ingenuity

Horace Silver – Song for My Father (1965)

Silver’s most celebrated album, combining soulfulness with sophisticated hard bop compositions.

Sonny Rollins – Saxophone Colossus (1956)

A hard bop essential, featuring the iconic “St Thomas” and Rollins’ unparalleled improvisation

Miles Davis – Workin’ with the Miles Davis Quintet (1956)

Part of the legendary Prestige sessions, it highlights Davis’s hard bop sensibilities with a stellar lineup

Cannonball Adderley – Somethin’ Else (1958)

A lyrical, bluesy hard bop masterpiece, with contributions from Miles Davis

Lee Morgan – The Sidewinder (1964)

A classic hard bop album with a funky edge, Morgan’s title track became a crossover hit

Hank Mobley – Soul Station (1960)

Mobley’s finest hour, blending smooth tenor sax lines with a hard-swinging rhythm section

Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers – Hard Bop (1957)

As discussed, an essential album defining the hard bop genre

Freddie Hubbard – Open Sesame (1960)

Hubbard’s debut album, showcasing his fiery trumpet style and hard bop sensibility.

Cool Jazz and Bop Hybrids

Dave Brubeck – Time Out (1959)

A cool jazz masterpiece with complex rhythms and melodic appeal, bridging bop and innovation

The Modern Jazz Quartet – Django (1956)

A cool yet soulful blend of classical influences and bebop improvisation

Gerry Mulligan Quartet – Jeru (1954)

Baritone saxophonist Mulligan’s elegant and airy cool jazz compositions shine

Stan Getz – Focus (1961)

Getz’s blend of lyrical cool jazz phrasing and orchestral backing reflects bop’s evolution

Post-Bop (Late 1950s–1960s)

John Coltrane – Blue Train (1957)

Coltrane’s first major statement as a leader, blending hard bop with his emerging modal approach.

Miles Davis – Kind of Blue (1959)

While modal jazz, it represents a culmination of bebop’s harmonic language, inspiring generations.

Wayne Shorter – Speak No Evil (1964)

A post-bop gem, blending advanced harmony, lyrical compositions, and Shorter’s bold tenor sax voice

Jack Kerouac

A Spontaneous Bop prosody

The Beat Generation emerged in the post-World War II era, a time of conformity and burgeoning consumerism in the United States. In stark contrast, the Beats were seekers, yearning for spiritual enlightenment, personal freedom, and authentic experience Kerouac, alongside figures like Allen Ginsberg, William S Burroughs, and Neal Cassady, became emblematic of this countercultural wave. The Beats rejected the rigid structures of mainstream society, and jazz specifically bebop provided the perfect metaphor and framework for their rebellion Bebop, with its complex harmonies, rapid tempos, and emphasis on improvisation, revolutionized jazz in the 1940s Pioneered by artists like Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, and Thelonious Monk, bebop was not music for dancing but for listening, an intellectual and emotional journey that demanded engagement Its practitioners pushed boundaries, challenging both their technical abilities and the expectations of their audience. For Kerouac, bebop was more than just music; it was a way of life He often described it as the sound of freedom, chaos, and raw emotion, capturing the restless energy he sought to emulate in his prose Kerouac’s masterpiece, On the Road, is perhaps the most vivid illustration of jazz’s influence on his writing The novel, written in a spontaneous burst of creativity on a single scroll of paper, embodies the freeform, improvisational nature of bebop Its sentences pulse with rhythm, and its narrative flows like a saxophone solo, veering off into unexpected directions yet always returning to its central themes of wanderlust, friendship, and the search for transcendence Kerouac himself likened his writing style to the "first take" philosophy of jazz musicians raw, unfiltered, and immediate This "spontaneous prose " technique, which Kerouac developed, sought to capture the immediacy of lived experience Like a jazz musician riffing on a theme, Kerouac eschewed traditional grammatical structures and linear storytelling in favor of long, winding sentences that mimicked the ebb and flow of thought He often wrote under the influence of music, allowing

the syncopated rhythms of bebop to guide his pen In Visions of Cody, a semi-autobiographical exploration of his relationship with Neal Cassady, Kerouac’s prose becomes even more experimental, bursting with fragmentary impressions and streamof-consciousness passages that mirror the improvisational solos of Parker or Gillespie

The Beat movement’s affinity with jazz extended beyond its stylistic influence on writing Jazz was the soundtrack to their lives, a shared passion that united the Beats in their bohemian haunts and late-night gatherings Clubs like Minton’s Playhouse in Harlem or the Five Spot Café in Greenwich Village became sanctuaries where Beats and musicians alike could commune in their shared rejection of societal norms For Kerouac, these spaces were sacred, offering a glimpse of the transcendence he so desperately sought Jazz also provided the Beats with a model for community and collaboration. Just as bebop musicians engaged in call-and-response, trading solos and building on each other’s ideas, the Beats inspired and challenged one another Kerouac’s friendship with Neal Cassady, for example, was as improvisational and intense as a jazz duet, with Cassady’s frenetic energy and stream-ofconsciousness storytelling serving as a catalyst for much of Kerouac’s work Similarly, Ginsberg’s poetry and Burroughs’ experimental prose pushed Kerouac to explore new creative territories, much like the interplay between musicians in a jam session. Thematically, the Beats and bebop shared a preoccupation with freedom and transcendence For bebop musicians, improvisation was a form of liberation, a way to break free from the constraints of traditional jazz and express their individuality For Kerouac and the Beats, the road, the poem, and the novel became vehicles for similar explorations. Their works often grapple with themes of alienation, spirituality, and the quest for authenticity in a conformist world

In The Subterraneans, Kerouac explicitly draws on his experiences in the jazz clubs of San Francisco, weaving the music and its culture into a story of love and loss that is as ephemeral and bittersweet as a jazz ballad

It’s important to note, however, that the Beats’ relationship with jazz was not without its complexities. While they revered the music and its creators, they often romanticized and appropriated aspects of Black culture without fully engaging with the systemic racism that shaped the lives of the musicians they idolized Kerouac and his contemporaries were undeniably influenced by the vitality and originality of jazz, but their engagement with it sometimes veered into the realm of fetishization, reflecting broader cultural tensions of the time

Despite these critiques, the legacy of Kerouac and the Beats is inextricably linked to jazz

Together, they forged a new artistic language, one that celebrated improvisation, spontaneity, and the unfiltered expression of emotion Kerouac’s writing, like a bebop solo, continues to resonate with its urgent rhythms and timeless quest for freedom. The Beat Generation, much like the jazz musicians who inspired them, left an indelible mark on American culture, reminding us of the power of art to challenge, inspire, and transcend

their engagement with Bop sometimes veered into the realm of fetishization

THE BIRTH OF THE COOL

West Coast Cool

The mid-20th century marked a period of remarkable evolution in American music, with jazz at its creative epicenter. Among the many styles that emerged, West Coast or "Cool Jazz" distinguished itself through its relaxed tempos, sophisticated arrangements, and a refined aesthetic that stood in contrast to the fiery intensity of bebop Rooted in California’s laid-back cultural vibe and driven by an influx of talented musicians, Cool Jazz became a defining genre of the 1950s, leaving an indelible mark on the jazz tradition and American popular music

Cool Jazz didn’t appear in a vacuum. Its origins trace back to the late 1940s, with pioneers like Miles Davis, Gil Evans, and Gerry Mulligan experimenting with a more measured, nuanced approach to jazz

The landmark 1949-1950 recordings known as *The Birth of the Cool* sessions set the template for the style, emphasizing intricate arrangements, subtle dynamics, and a departure from bebop’s frenetic energy

California’s post-war boom attracted musicians from across the country The state’s burgeoning film and recording industries, coupled with a growing appetite for modern jazz, made the West Coast a fertile ground for experimentation. Cool Jazz found its natural habitat in the sun-soaked urban centers of Los Angeles and San Francisco, where an audience seeking sophistication embraced this fresh sound.

West Coast Cool Jazz was characterized by its relaxed rhythms and subtle dynamics, which contrasted sharply with the aggressive tempos of bebop. This laid-back groove created space for intricate melodic and harmonic interplay, offering listeners a chance to savor the music’s subtleties The genre also stood out for its complex arrangements, often influenced by classical music, with counterpoint and formal structures lending it a chamber-like quality.

Instrumentation played a significant role in shaping Cool Jazz’s unique sound. Smaller ensembles were the norm, and musicians often explored unconventional pairings, such as alto saxophone with French horn or tuba, to produce distinctive timbres While improvisation remained central to the style, it prioritized group cohesion and thematic development over virtuosic soloing, emphasizing a more restrained and reflective approach

Several artists and groups epitomized West Coast Cool Jazz, each contributing their own flair to the genre The Dave Brubeck Quartet, for instance, pushed boundaries with innovative uses of odd time signatures, exemplified by their 1959 album *Time Out*, which featured the iconic track “Take Five.”

Meanwhile, Chet Baker, both as a trumpeter and vocalist, captured the essence of the cool aesthetic through lyrical playing and hauntingly understated singing

Gerry Mulligan’s contributions were equally significant As a baritone saxophonist and arranger, his piano-less quartet with Chet Baker became a defining sound of the early 1950s. Stan Getz, known as “The Sound,” brought a warm, velvety tone to his tenor saxophone playing, and later collaborations with Brazilian musicians introduced bossa nova to the jazz repertoire Finally, Shorty Rogers and His Giants blended swing, bebop, and cool jazz into a style that was as distinctive as it was accessible

The West Coast’s jazz scene revolved around legendary venues like The Lighthouse in Hermosa Beach, where bassist Howard Rumsey led the Lighthouse All-Stars, and San Francisco’s Black Hawk These clubs fostered a vibrant community of musicians and listeners who celebrated the artistry of Cool Jazz.

The proximity to Hollywood studios also played a role Many jazz musicians found work scoring films and television, further refining their compositional and arranging skills. The cinematic quality of Cool Jazz, with its evocative moods and textures, often paralleled the visual storytelling of mid-century film noir

Cool Jazz emerged during a period of significant cultural change in America. Its emphasis on sophistication and subtlety resonated with the country’s growing middle class, eager for art forms that mirrored their aspirations. The genre also reflected California’s post-war optimism, with its sunshine-drenched locales and promise of reinvention

However, Cool Jazz was not without controversy. Some critics accused it of being overly intellectual and detached, contrasting it unfavorably with the emotional immediacy of bebop and hard bop. Others pointed out the racial dynamics of its popularity, as many Cool Jazz icons were white musicians benefiting from a genre rooted in African American innovation

By the late 1950s and early 1960s, Cool Jazz began to wane as hard bop, modal jazz, and free jazz took center stage Nevertheless, its influence persisted The emphasis on arrangement and texture informed later developments in jazz and popular music, including the fusion styles of the 1970s and the smooth jazz of the 1980s Artists like Pat Metheny and even certain aspects of indie music today owe a debt to the Cool Jazz ethos

West Coast Cool Jazz represents a unique chapter in the history of jazz a period where artistry and accessibility coalesced into a sound that was as thoughtful as it was pleasurable Though its heyday was brief, the genre ’ s legacy endures, a testament to the timeless appeal of music that dares to take a deep breath and savor the moment For listeners and musicians alike, Cool Jazz remains a reminder that sophistication and soulfulness can harmonize in the most beautiful ways.

"At this time, 1947, bop was going like mad all over America. The fellows at the Loop blew, but with a tired air, because bop was somewhere between its Charlie Parker Ornithology period and another period that began with Miles Davis. And as I sat there listening to that sound of the night which bop has come to represent for all of us, I thought of all my friends..."

Kerouac