The Confluence summer 2024

Change is the only constant in life. Here at SVC, we have been experiencing many changes throughout the year so far. We are now six months into our new co-leadership model, having said farewell to Rebecca Ramsey, our previous executive director, at the end of February. In her place, SVC has established a leadership team of three managing directors, Sara, Ty, and myself, as our version of a co-leadership model, which many nonprofits throughout the nation are implementing. I’m happy to report that midway through the year we and our amazing, talented staff and board have made great progress in our transition and have continued to offer all of the same SVC conservation and education program services that you have grown to expect. We’ve even added additional opportunities and partners, such as a citizen science project with the Owl Research Institute to learn more about the owls that call the Swan Valley home and locate nesting territories, all of which will better inform the protection of these sensitive sites. This is just another way we add capacity and help inform management decisions by agency partners when planning future activities. We’re ecstatic to have Ty on board as our managing director of development and philanthropy and have already realized financial growth and stability from having a position focused solely on fundraising.

As we spring into summer, our education program staff are busy coordinating and teaching our Wildlife in the West college field semester course, hosting various tracking classes, and leading tribal youth from the Mission Mountains Youth Crew. All of these programs are connecting people with the natural world, sharing more about careers in natural resources, and training the next generation of conservation leaders. Our conservation staff are busy planning and conducting high-priority fuels reduction treatments around people’s homes and access roads, building electric fences to prevent bears’ access to unnatural human attractants, and distributing bear-resistant trash cans, just to name a few ongoing efforts.

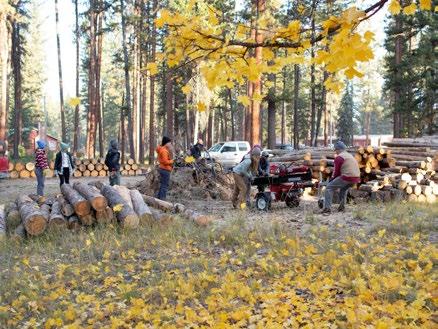

But the biggest and most unexpected change was that the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) plans to sell our beloved Condon Work Center, and we’ve been told to seek an alternative home base by the time our current partnership agreement expires in March 2025. This is the place that SVC calls home for our office space, the visitor center, the place to interact with community members and visitors to provide valuable information and education, our meeting place with partners and constituents, the base of operations for local wildfires, the site of our annual community firewood day, and so much more. The Condon Work Center is the place we’ve called home since 1996. When the USFS originally wanted to mothball the facility, one of our parent organizations, Swan Ecosystem Center, formed a partnership with the USFS to maintain and run the visitor center for the benefit of the community and visitors, by providing information and education, while maintaining a USFS presence in the Upper Swan Valley. While this has been our home for nearly thirty years, I often marvel at the several-hundred-year-old culturally modified ponderosa pine trees just outside of our office, and think about the Indigenous tribes that have called this place home since time immemorial.

While we are still learning more about the process and timelines for the USFS to convey the Condon Work Center, we do know that the USFS process will include completion of a land survey for the facilities and land, appraisals of the property, going through the NEPA process, and public scoping, before the property would go up for bid. One thing we know is that SVC, other conservation organizations, and community members have accomplished a successful history of land conservation; this culminated with the Montana Legacy Project, Montana’s largest land conservation deal that prevented the development of 67,000 Swan Valley acres of

Swan Valley Connections

6887 MT Highway 83

Condon, MT 59826

p: (406) 754-3137

f: (406) 754-2965

info@svconnections.org

Mary Shaw, Chair

Jessy Stevenson, Vice-Chair

Donn Lassila, Treasurer

Kathryn De Master

Rachel Feigley

Zoë Leake

Dan Stone

Rich Thomason

Aaron Whitten

Tina Zenzola

Emeritus

Russ Abolt

Anne Dahl

Steve Ellis

Melanie Parker

Tom Parker

Maria Mantas

Neil Meyer

Rebecca Ramsey

Advisors

Kvande Anderson

Steve Bell

Jim Burchfield

Larry Garlick

Chris La Tray

Tim Love

Alex Metcalf

Pat O’Herren

Casey Ryan

Mark Schiltz

Lara Tomov

Mark Vander Meer

Gary Wolfe

Staff

Luke Lamar, Managing Director

Sara Lamar, Managing Director

Ty Tyler, Managing Director

Andrea DiNino

Kirsten Frazer

Mike Mayernik

Jackie Pagano

Uwe Schaefer

Taylor Tewksbury

The Confluence is published by Swan Valley Connections, a non-profit organization situated in Montana’s scenic Swan Valley. Our mission is to inspire conservation and expand stewardship in the Swan Valley. Images by Swan Valley Connections’ staff, students, or volunteers, unless otherwise noted. All rights reserved to Swan Valley Connections. Change service requested. SwanValleyConnections.org

Plum Creek Timber Company lands that would have forever changed the wild, rural character of the Swan Valley. The thought of USFS lands, our public lands, being sold to the highest bidder and becoming private property does not sit well with me and many others.

While SVC is in the beginning stages of exploring if we are interested in pursuing the property for our own uses, as well as other potential community benefits, we are also preparing for the unknowns if we are not able to stay in our office space past March 2025, and looking at alternative long- and short-term options. Needless to say, all of these options come with financial costs, whether that is purchasing the Condon Work Center, renting other office space and storage units, or installing short-term options or building long-term solutions on our currently undeveloped Swan Legacy Forest property. In the meantime, we have requested that the USFS allow us to stay in the office past March, while they go through the conveyance process. We do not yet have an answer for this request.

For this reason, we need you, our supporters, more than ever. Support can range from making additional donations to help with these costs, to contacting USFS personnel to urge them to let us stay in our office space, to calling or emailing your elected officials. As always, our door and office are open here at the Condon Work Center (for now), and we welcome any thoughts, ideas, or discussion as we continue with this process.

One thing I know for certain is that the Swan Valley contains a passionate human community that is as wild and resilient as our ecosystems. Wherever this process leads, SVC will continue to face changes and challenges like we have so many other times in our organization’s history, and I’m sure we’ll continue to be a leader for inspiring conservation and expanding stewardship in the Swan Valley and beyond, as we continue to grow and mature as an organization.

Onward & Upward,

Luke Lamar, Managing Director- Conservation & Operations

SVC has maintained a beneficial partnership with the USFS, which has benefited both the USFS and SVC’s missions. (The Condon Work Center is an important place for carrying out all of these partnerships, and provides a community hub for information and education dissemination. Without it, the community ties to the USFS will be nearly nonexistent.)

All of our projects/programs and partnerships combined have accomplished $11,367,000 of work since SVC’s origin.

In total, the USFS has contributed $1.27 million towards these efforts. SVC has leveraged those funds, contributing $6.23 million while working with other partners to provide $3.87 million in funding towards those same efforts.

Read more about the history of the Forest Service presence in the Swan and the Condon Work Center on page 8 and find USFS contact information on page 10.

Meet the cover artist:

Kaetlyn grew up in and around the suburbs of Boston, Massachusetts. She studied art at Wellesley College, received an MFA from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and moved to Southwest Montana in 2011. She finds inspiration in the history, flora and fauna of the American West.

“I make black and white portrait drawings of animals interlaced with colorful little worlds of painted flora, birds and insects. The black and white areas of my work are drawn with tattoo needles on scratchboard panels. The colored elements are painted in acrylics.

I love observing, learning and wondering about wildlife, from our big Rocky Mountain fauna to the tiniest little garden spider. I’m especially interested in the similarities and connections between human beings and wildlife.”

See more of her stunning artwork at www.kaetlynable.com

By Taylor Tewksbury

The sound of your own labored breath cuts through the stillness as you post-hole through early-spring snow. As you approach the edge of a newly awakened meadow, a flash of gray feathers zips past the still-sleeping aspens. As you reach for your binoculars, two golden eyes blink back at you from the outstretched branch of a cottonwood tree. Your eyes lock on the bird’s massive size, the vole dangling from its tightly clenched beak. Then, just as quietly as it came, the Great Gray Owl disappears again into the forest.

Fleeting moments such as this offer a rare glimpse into the life of one of North America’s largest owl species. Despite their size, Great Grays remain enigmatic, maneuvering the forest in near silence. More research is still needed to understand the raptor species and their needs, so we can better live on the landscape with them.

This spring, the Owl Research Institute (ORI) partnered with Swan Valley Connections to better understand this elusive species and their habitat within the Swan Valley. Based in Charlo, Montana, ORI is a non-profit organization dedicated to owl and wildlife conservation through research and education. To increase knowledge on Great Gray nesting needs, ORI has spent years monitoring known nest sites and surveying new areas for breeding pairs. Beginning in March, Great Gray owls nest in large, broken-top trees, called snags, which must be able to accommodate the bird’s massive size. Through their research, ORI aims to inform responsible management of these unique snag features and key Great Gray nesting habitat.

For many landscape-scale monitoring efforts, data collection is time-intensive, which can limit the reach of a project.

However, by training SVC volunteers on their field protocol, ORI was able to expand their Great Gray work in the Swan Valley. From late February to early April, volunteers deployed ARUs, or autonomous recording units, across the valley. From dusk to dawn, these ARUs recorded the sounds of the forest, including Great Gray vocalizations. ORI then analyzed the data collected by these units to identify potential nesting sites in the project zone.

Thirteen volunteers contributed roughly 300 volunteer hours to the project, covering a lot of ground in the process. SVC volunteers deployed a total of 61 ARUs, 47 of which detected owls. In addition to Great Gray owls, the ARUs deployed around the Swan Valley detected Northern Saw-whet, Northern Pygmy, Barred, Great Horned, and Long-eared owls. These detections may provide insight into breeding pairs in the valley that were previously unknown, which is a great starting point for future studies.

These outcomes would not have been possible without the volunteers who generously contributed their time and knowledge of the valley to this project. SVC would like to thank Tina Zenzola, Nick Gistaro, Chris Moore, Jan Moore, Mary Shaw, Mark Benedict, Rob Rich, Helene Michael, Mark Leffingwell, Sharon Lamar, Steve Lamar, Anne Dahl, and Amber Langley for their efforts this spring.

SVC would also like to thank ORI’s Beth Mendelsohn and Troy Gruetzmacher for sharing their expertise, as well as the opportunity to learn and partner with them through the project. If you would like to learn more about ORI’s work or would like to report a Great Gray nesting site, please visit www.

owlresearchinstitute.org. Remember, Great Grays are highly sensitive to disturbance, and harassment of nesting locations can lead to negative outcomes for the birds. Please do not visit known nesting areas unless you are working with ORI to collect data.

If you would like to support projects like these, please consider donating to our June Ash Memorial Bird Fund! If you are interested in getting involved in future citizen science opportunities with SVC, please contact our Education Program Coordinator, Taylor Tewksbury at taylor@ svconnections.org.

And if you’d like to hear more about the project, make sure to join us at the Swan Valley Community Hall for our quarterly potluck & presentation on Wednesday, August 7th, where we’ll be joined by ORI and a handful of our volunteers.

By Kayla Heinze

I’ve been told that trees have the best memories, their roots as long as their patience in the sun. But every time you put your curious nose to the dirt I too could remember the soil’s remembrance, nearly tasting the new beginnings and spring morels.

Like the novels of the ponderosas, our paths tell the truth that this world’s beauty won’t always be pleasant which is why the sun remains, after you have gone. A deep fire scar, love is the darkest soot, it never leaves this land. You the footfalls and me the mud that holds them still.

For it is only in the clearing of loss that tomorrow can set seed so in this ashy soil I am arnica, sprouting, and I can promise when the forest burns the green doesn’t vanish it just dances, briefly, as smoke against the sky— our weathered hearts wisest when we remember.

Kayla Heinze was our Resident Education Assistant this summer. Her regular role is the Communications and Outreach Coordinator for The Vital Ground Foundation. She enjoys working at the intersection of science, sustainability, and storytelling.

By Kayla Heinze

During our first week in the valley, we tramped through the emerging skunk cabbage and pre-mosquito swamp to place a game camera on a bear bath site. Six weeks later, at the end of our course, we returned. Now battling squadrons of mosquitos and thick brush scratching us up to our knees and waists, we collected the footage showing all that had transpired at the spot while we’d been exploring the rest of the valley and beyond for SVC’s Wildlife in the West class. We watched as grizzlies, black bears, mink, deer and ducks wandered in front of the camera and wondered about what other creatures might have been lurking just out of view. Less than a mile as the crow flies (or raven…we saw plenty of those too) from the barn where we’ve been staying, it’s fair to say these creatures truly constitute backyard wildlife.

A 9-credit college course drawing students from across the country, Wildlife in the West focuses on threatened and endangered species conservation and their interactions with rural communities. With so many of those species making use of the Swan Valley, we were often attuned to this hyperlocal scale of backyard wildlife. We learned to note the differences between felid and canid tracks, as to tell which creatures were roaming our shared roads and trails. We got to know the valley intimately (perhaps a little too much) as we practiced identifying a variety of scats around Condon.

But the class also required, as much conservation work in Montana does, a lot of driving. We spent a week roaming the Flathead Valley, visiting with staff from the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes and talking about the landscapewide debates involving native fish conservation and bison reintroduction. Later we hauled through the Blackfoot Valley, stopping to talk with ranchers, trappers, and conservation specialists. From there we made our way over to the grasslands of the Rocky Mountain Front, where we heard from, among others, Blackfoot Confederacy members about bison and Montana Department of Fish Wildlife & Parks staff about their

conflict prevention work with grizzly bears. These wide- scoping conversations marinated in our minds as we took in the Crown of the Continent ecosystem at the broad scale that comes with spending hours on the highway.

While many of the students are studying and living in places that do not harbor the same suite of predators, large mammals, native birds, and fish that the Swan Valley does, both the hyperlocal and landscape-scale lessons they’ve learned here will serve them well. Wherever we are, conservation requires us to marry a love for the most detailed and delicate biological realities with the big picture thinking that can protect those realities. As they make careers in environmental law, riparian restoration, marine biology, recreation management and more, the wisdom of this valley, with its precious ecological richness and diverse stakeholder usage, will, at least in small ways, be with them.

At the bear bath, the ducks laid eggs and the plants grew taller towards the sun each passing week. It stayed light out longer as the footage neared the solstice and the end of our time in this special place. The whole time, as the landscape changed around us, we were changing too—becoming more nuanced, informed and passionate in our understandings and approaches to collaborative wildlife conservation. Headed back to our respective lives and undertakings across the U.S., we can now see more clearly, even if more complexly, a path forward for vulnerable species and the people who live with them. Like placing our game camera at the bear bath, we’ve focused our field of view based on past observations and our faith in the future. Watching these students learn, I feel this faith vividly. I trust that while they might complain along the way, they will wear every bug bite and bruise as a badge of honor that they are rising to the worthy challenges of conservation here in the Swan Valley and beyond.

By the Upper Swan Valley Historical Society

Throughout the years, the Forest Service has had a lasting impact on the landscape and culture of the upper Swan Valley. Many residents were employed by the Forest Service from the local teenagers on the Young Adult Conservation Corps (YACC) crews, to the seasonal trail crews, fire crews, planting crews, spraying crews, building crews, fire lookouts, to the full-time employees. The Condon Work Center has remained an important part of the fabric of the community.

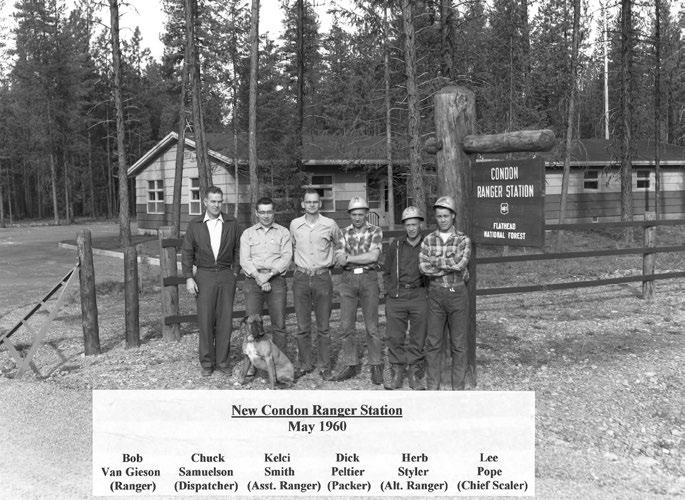

When the Forest Service decided to build a new ranger station near the airstrip and partially completed highway in the upper Swan Valley in 1957, Bob Van Gieson played a key role in planning the new administrative site. As the ranger at the Condon Ranger District from 1955-1959, Van Gieson came on duty at a time of increased logging and road-building. He witnessed the spruce bark beetle salvage logging operation in the mid-to-late 1950s.

“The logging came on real big…They [USFS] could see the need for some pretty good roads there in the Swan Valley. They got the Bureau of Public Roads to build the Kraft Creek and the Cold Creek Roads…They were built to primarily access these beetle-infested areas,” Van Gieson recalled in an interview with historian Suzanne Vernon.

Back then, the Condon Ranger Station was located near Condon Creek on present-day Condon Loop Road. It served as a year-round base of operations for the trail crews, packers, lookouts, and fire guards. Today, the historic site is known as the Old Condon Ranger Station.

In a letter to the USFS archeologist Gary McClean, Van Gieson wrote, “I received a radio message one day…that I was to develop a site plan for a new station and submit a properly drawn plan for this station – all to be done within the next three days.”

The construction began in 1957. “Buildings were situated within and around a U-shaped station driveway. It contained two permanent residence sites, a several-stall garage, a combination office-warehouse, and a centrally located well site,” Van Gieson wrote.

The third residence was moved to the site from the Hungry Horse dam project, and is now called the Condon House. Later in 1962, the Forest Service built a kitchen, and bunkhouses were also added to the site.

Landscaping was a concern at the new ranger station. “We tried not to do anything that would detract from the “natural forest” appearance…I made certain the grove of ponderosa pines in front of the office were preserved,” Van Gieson wrote.

In those days the Forest Service often employed local residents of Swan Valley. “They wanted people who knew the country,” Herb Styler explained in an interview with Suzanne Vernon.

Styler witnessed many changes during his tenure working for the Forest Service from 1953-1977. He headed up the trail crews, cruised timber, and fought fires. He was promoted to Alternate Ranger, later known as the fire control officer. Early on, he and his family lived at the Old Condon Ranger Station, before they moved to the Condon House at the new administrative site.

In 1973, the Condon Ranger District was combined with the Swan Lake District, and many of the full-time employees were moved to the administrative site located in Bigfork. The facility at Condon became known as the Condon Work Center. “It was sad…That ranger station anchored the whole community. The amount of employment it provided was incredible,” Suzanne Vernon said in a Michael Jamison Missoulian article.

When Cal Tassinari first worked at the Condon Ranger District in 1960, most of the trailheads were located in the valley bottom. “One in particular that I can remember, Piper Lake, was about 16 miles from the trailhead. And now it’s about five and a half,” he explained in an interview with Suzanne Vernon.

Tassinari came from the Clearwater District in Idaho after Condon District Ranger Fred Matzner (1960-1962) encouraged him to transfer. “At that time we were getting fifteen or twenty thousand dollars a year to build trails to an “all-purpose standard,” Tassinari said.

Later on, Tassinari became the first Wilderness Ranger in Region One, overseeing the management of the Mission Mountains Wilderness. He worked with District Ranger Jack Dolan (1969-1973) to develop a Wilderness management plan that emphasized education. “Few Wilderness areas have had the quality care that this one has,” Tassinari said. “Local people know the area intimately and can provide managers with good information,” he shared.

Perhaps the longest-serving Forest Service employee in the upper Swan Valley was Leita Anderson, who worked 43 seasons. She started working as a cook’s assistant in the fall of 1959 and was promoted to head cook at the Condon Work Center in 1975.

In 1988, the year of the Scapegoat Wilderness Fire and dozens of other local fires, Leita and her crew of local women prepared over 20,000 meals in the kitchen at the Condon Work Center. A Seeley Swan Pathfinder article in 1988 reported, “Firefighters in the hundreds have been bedded down at the Work Center buildings, tents, and the Community Hall…This facility is one of the few Forest Service facilities left that is capable of handling situations of this magnitude.”

Leita Anderson was widely loved and contributed an incredible amount to the community. She passed away this year and will be deeply missed by many. A celebration of life will be held on July 20, 2024 at 1PM at the Swan Valley Community Hall

In the early 1990s, the local timber economy was sagging, and tensions between conservationists and loggers were running high. Under the leadership of Rod Ash, residents formed the Swan Citizens’ ad hoc Committee in 1990 to maintain and enhance both the economic livelihood and the quality of life in the Swan Valley. The common thread of love of the Swan brought together an unlikely alliance of loggers, conservationists, developers, outfitters, old-timers, and newcomers. The ad hoc committee members were determined to define themselves by the things they agreed on, not the things that divided them.

Professional facilitator and resident, Alan “Pete” Taylor volunteered to help community members communicate effectively about sensitive issues and build consensus. There were no by-laws, no president, or officers. Everyone got a chance to be heard, and everyone listened with respect. Flip charts were used to display each speaker’s main points. At the end of each meeting, new co-chairs would volunteer to guide the next.

Through consensus-building collaboration, the ad hoc committee encouraged more local involvement in Forest Service land management decisions. The committee worked with the USFS staff to promote small salvage sales by local loggers.

In 1995, the ad hoc Committee worked with the USFS staff on the 30-acre Ponderosa Pine Restoration Project north of the Condon Work Center to restore the forest to a historic, park-like condition. That same year, the USFS announced the pending closure of the Condon Work Center. Alarmed at the possible lack of a Forest Service presence in the Swan Valley, the ad hoc Committee decided to apply for nonprofit status to facilitate fundraising efforts.

Many of the ad hoc subcommittee members of the Ponderosa Pine Restoration Project became the first Board of Directors of what became known as the Swan Ecosystem Center (SEC). The first board members included Rod Ash, Bob Cushman, Sue Cushman, Anne Dahl, Neil Meyer, Tom Parker, and Mary Phillips.

“We decided, rather than just whine, to see what we might be able to do to keep the Forest Service here, and maybe even become a better manager of the area, and that there would maybe be more involvement with the citizens,” Rod explained in an interview with Suzanne Vernon. “We were looking at ways in which we might be able to cooperate with the Forest Service and keep the place open,” he said.

With the support of District Ranger Chuck Harris, the Forest Service agreed to form a partnership with SEC to keep the Condon Work Center operational. This collaboration allowed SEC to act as a liaison between the Forest Service and the public. Tourists and locals alike could continue to stop in at the visitors center to get up-todate information about trail conditions, fishing regs, and camping sites.

In 1996, SEC applied for a grant to pay someone to write the articles of incorporation and apply for nonprofit status. “So we looked at the group, and only one person could use a computer, and that was me,” Anne Dahl said in an interview with Steve and Sharon Lamar.

With her newly acquired grant-writing skills, adept problem-solving ability, and tactful communication skills, Dahl was soon hired as the executive director of SEC.

That same year, when the Forest Service announced they would no longer fully fund the wilderness ranger contracts in the Mission Mountains and the Swan Front, SEC spearheaded fundraising efforts to match federal funds to keep the rangers working.

SEC’s staff focused on forest stewardship, outdoor education, local history, and scientific research. To sustain the land and boost the economy, SEC partnered with many public and private entities over the years to complete stewardship projects. In addition to partnering with the USFS to keep the Condon Work Center office open, SEC built a wheelchairaccessible trail within the Ponderosa Pine Project called the Ever-Changing Forest Trail. Dahl secured grant funding from the Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation (DNRC) to help private landowners with fuel reduction projects. Funds were also secured from the Missoula County Weed District to help landowners reduce weeds on their property. SEC also partnered with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to complete wetland restoration projects and to conduct waterfowl counts.

In the late 1990s SEC partnered with another local nonprofit, Northwest Connections, to form Swan Valley Bear Resources, a group whose mission was (and still is) to promote coexistence between people and bears. “It was a really bad berry year. Many bears had been transferred or had to be euthanized, and Kathy Koors, who has been a warm-hearted animal lover, couldn’t take it. So, we started searching for funding…We applied to Disney for an emergency fund to get the bear-resistant dumpsters,” Dahl said.

During the Crazy Horse fire in 2003, the Forest Service used the Condon Work Center as their headquarters, while the Incident Command Post was set up at the Gordon Ranch. The fire incident commander kept the SEC staff informed, so they could answer questions from the public.

In 2016, the Swan Ecosystem Center and Northwest Connections merged into a single entity and was renamed Swan Valley Connections (SVC). Today, SVC continues to partner with the Forest Service to engage in projects that support economic activity and natural resource stewardship.

Since 2006, the Great Northern Fire Crew has been stationed at the Condon Work Center when not on fire assignments. A Type 2 Initial Attack Crew, the group rented the bunkhouse, kitchen, and other facilities at the site.

“I think it’s a good idea to make use of the place,” said longtime smokejumper Mike Patten in the Michael Jamison Missoulian article in 2007. “The Forest Service seems to be shifting more to the urban areas. This is more like the old-time Forest Service, being out here in the woods with the barracks and the mess hall. Once you close a place like this, it’s forever. It’d be a shame to lose a spot like this,” he said.

In June 2024, District Ranger Chris Dowling announced the impending sale of the Condon Work Center.

Interested in letting the USFS know about your thoughts on their decision to sell the Condon Work Center and/or informing SVC to seek alternative office space elsewhere? If so, please contact:

Chris Dowling • Swan Lake District Ranger 406-837-7500, chris.dowling@usda.gov

Anthony Botello • Flathead National Forest Supervisor 406-758-5208, anthony.botello@usda.gov

Leanne Marten • Regional Supervisor 406-329-3315, leanne.marten@usda.gov

By Andrea DiNino

Close your eyes and picture an item that’s been in your family for generations. Or maybe a photo of your grandparents when they were younger. How does the item, or items, make you feel? Does it fill you with a greater sense of who you are and where you came from? These physical items allow us to form a deeper connection to the people and places we came from; the tangible links us to the history, in a way that simply hearing about those times and individuals cannot. Maybe they also serve as reminders or symbols for family values.

I can picture an old black and white photo of my grandfather, Settimio (or Sam, as he went by here in America) from Italy. He’s leaning against a shiny, beautiful classic car, and he’s wearing dress pants and a button-up shirt, with his sport jacket flopped over his arm. He’s got a wide smile on his face. While he passed away when I was in the first grade, I can still picture that same smile while he pushed me on the swing set in our backyard. When he came to America, he started a towing and auto body business, the same business that my father and brother run today, and the place my nephew had his “first day of work” at the age of 12 just last week.

My dad has always worked hard and taken care of the things he owned, be it cars or any other machine. And he instilled those values in his children. One time when he first came to visit my sister and me in Montana, we ran through the car wash three times in one week (twice in a single day); he had not yet conceded to dirt roads during mud season. But I know these values came from my grandfather, and I’m reminded of that when I look at this photo.

That’s just going back one generation. I wish I had more connecting me to my great-grandparents, great-greatgrandparents, and so on.

Tim Ryan, department head of the Culture and Language Studies and Indigenous STEM instructor for the Salish Kootenai College Native American Studies Division, was one of those people who helped to map out most of the CMTs in western Montana, from the Flathead Reservation and around Flathead Lake, up to Eureka, deep into the Bob Marshall Wilderness, and down to the Bitterroot area. While Tim may not have a degree in archaeology, his on-the-job-training, background working with the Tribal Historic Preservation Office, and cultural knowledge all added valuable skills and knowledge to the joint effort between the Tribal and state preservation offices.

The Condon Work Center, where the Forest Service, Swan Ecosystem Center, Great Northern Fire Crew, and Swan Valley Connections have all called home, is also home to a stand of culturally modified ponderosa pine trees. And, it was home base for the Young Adult Conservation Corps (YACC), where Tim served as a crew leader from 1977-1978; the experience greatly impacted him and his life path. Tim remembers his first overnight trail clearing trip in the Jewel Basin while working with YACC. He was flown into the Jewel to clear trails and work alongside a Vietnam veteran. The man was kind, but barely spoke. During the day, Tim followed along behind him on the trail, clearing the branches and brush that were left behind from the chain sawing ahead. It’s one of the fondest memories he holds from his youth.

“...I can see the cultural values built into the scarring of these trees: take what you need, not more than that.”

Culturally modified trees (CMTs), or scar trees, are one of these special ancestral connections for Indigenous peoples. A CMT can be one of many tree species found here in northwest Montana, including ponderosa pine, whose bark was stripped in the springtime to reach the sweet cambium layer for eating, or river birch, utilized for its cambium, sap, and bark (which was used for several things, including basket-making for berry gathering). While trees can live for hundreds or thousands of years, many CMTs throughout the West have been lost to things like logging, development, and wildfire. Although one scarred tree on the Flathead Reservation has been dated back to 1743.

Montana has made a focused effort to find and map out the locations of these incredibly important cultural artifacts, and we’re lucky to have some vast areas where these trees have at least been protected from logging and development – in the national parks and Wilderness areas. In a Denver Post article, Montana’s state archaeologist, Stan Wilmoth, shared that “Montana spent more than a decade mapping and dating hundreds of scarred trees…The impetus to study the trees came from a ‘strong and articulate advocate’ in the form of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes.”

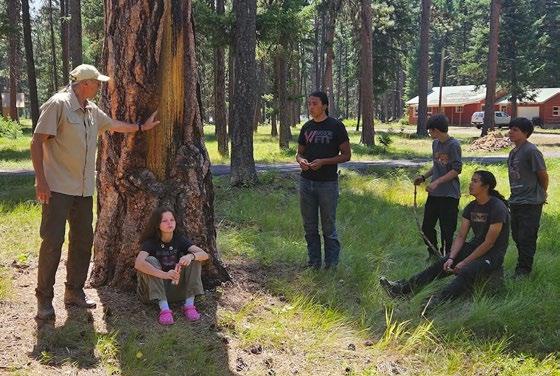

Today, life has come full circle for Tim, as he leads the Mission Mountains Youth Crew, an effort to expose Indigenous high school students to the careers and opportunities available in the field of natural resources. The group meets with different professionals in the field, helps with various projects, including trail clearing, and learns more about their cultural history on the landscape, their homelands. The past few years, Tim has introduced each crew to the scarred ponderosa pine trees at the Condon Work Center, sharing what these trees mean to him and others.

These trees, Tim shares, are on what was likely the historic wintering grounds of the Salish, Kootenai, and Pend d’Oreille, and are probably between 150-250 years old. The Swan Valley was used extensively by these tribes, and the places they wintered were often defined as home base; each winter season, they would return to these areas for the less intense weather and decent amount of resources offered. While there hasn’t been much archaeological study done on the river terrace above the Swan River, Tim imagines that would be the ideal spot for winter camping.

Once the snow melted, trees’ cambium layers would be one of the first sought-after food sources. In the spring, trees get a rush of nutrients and the sap-rich cambium layer offers a high content of simple carbohydrates, such as glucose, sucrose, and fructose, a welcomed treat after months of relying heavily

on dried meats and other preserved foods.

The scarred trees often mark the paths, trails, and mountain passes the tribes would use as they continued on with their subsistence lifestyle, harvesting the roots, bulbs, berries, and proteins that aligned with each season.

“[These trees] are living artifacts of my ancestors,” Tim shared. “Traditional ecological knowledge told them not to totally remove the bark from all around the tree, or they’d kill them...I can see the cultural values built into the scarring of these trees: take what you need, not more than that.”

Another value that seemed ever-present was “utilize every bit that you can.”

Trees offered so much more than the sweet treat of cambium. A birch tree could be stripped to get to the sweet sap, but its bark was also used for making baskets and containers, something lodgepole bark was also good for. A cedar’s fibrous bark lent itself to making rope. Engelmann spruce and white pines were preferred for their not-too-thick bark as a wrap for a cedar-frame canoe. Tim has also made spoons, dishes, and cups from tree bark…just some of the many uses of what he appropriately summed up as “bark technology.”

Tim continues to work closely with the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) Heritage Program Manager, who oversees these cultural properties within the National Forest, to prioritize protecting the CMTs.

Trees in the Bob Marshall Wilderness area may be safe from being cut down, but they are not safe from the threat of wildfire. In 2003 some CMTs were lost to a series of wildfires that occurred, and today there are vulnerable trees that remain at risk. One of Tim’s ideas and hopes is to form a workforce to make the two-day hike in and hand-clear ladder fuels (or smaller trees and brush) that have built up around the CMTs. (While the group would be open to anyone interested in helping, Tim hopes to connect more Indigenous youth and tribal members to their rich heritage found within these trees.)

Ryan with Mission Mountains Youth Crew at a culturally modified ponderosa pine

Traditional wester red cedar bark basket (right) and Engelmann spruce basket (below) made by Tim Ryan

Sunday, August 25, 2024 • 3pm-6:30pm the nest on swan river • bigfork, montana in the

Thank you to sponsors!our

Ticket includes: hors d’oeuvres • hosted bar • live music by Jessie Thoreson and the Crown Fire silent + online auctions www.SwanValleyConnections.org/summer-soiree-in-the-swan

Always check our website for more details and the most up-to-date information

July 24

Forest Insects & Disease Workshop with MT DNRC

July 24-28

Wildlife Field Techniques- LGBTQ+ Affinity Course (FULL) with Queer Nature

July 27

Swan Valley Bear Resources Bear Fair (Bigfork)

august 1

Living with Beavers Presentation with MT FWP

august 7

Quarterly Potluck - Great Gray Owl Project (ORI)

Swan Valley Community Hall

august 10-18

Weeklong Wildlife Tracks & Sign Course (FULL) + CyberTracker Certification

august 12

Online Auction OPENS

august 25

5th Annual Summer Soirée in the Swan The Nest on Swan River

august 26

Online Auction CLOSES

September 5-6, 12-13

MSU Forest Stewardship Extension Class

September 13-18

Montana Master Naturalist Course + Certification

October 2

Quarterly Potluck - Rare Carnivore Monitoring Update

Swan Valley Community Hall

October 3

Community Firewood Day Volunteer Opportunity