issue 3 | 2023

the quarterly of the Swedish Finn Historical Society

Publisher

©2023 All rights reserved. Inside This Issue A Brief History of the Art Nouveau Movement...5 Vernacular Finnish Log Construction in America...6 Replot Bridge...12 Capturing the Uncorrupted...14 John Hellund & His Swedish Finn Church...22 How Our Ancestors Lived...26

of a storage

Swedish Finn Historical Society 1920 Dexter Avenue North Seattle, Washington 98109 info@swedishfinnhistoricalsociety.org www.swedishfinnhistoricalsociety.org 206•706•0738

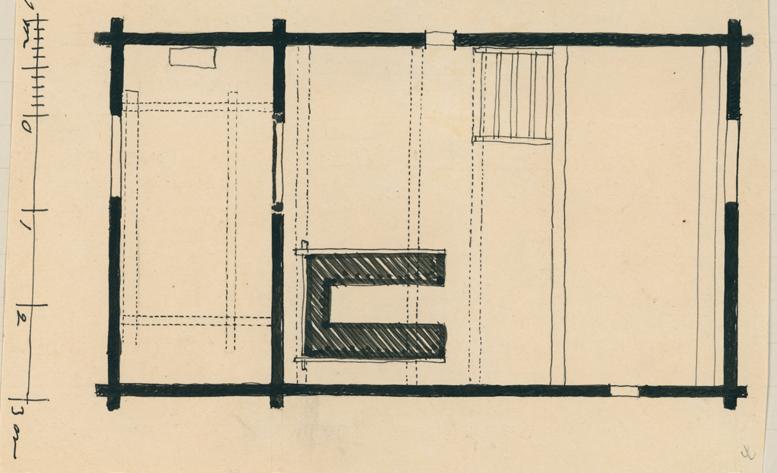

Illustration

building by Hilding Ekelund, 1914, Southeastern Ostrobothnian Commonwealth Buildings Collection, Society for Swedish Litterature in Finland.

Issue 3 December, 2022 Editor Cassie Chronic Layout & Design Kimberly Jacobs Editorial Staff Iona Hillman Toni Nelson Nancy Nygård Hannah Kourujärvi Guest Writers Frank Eld (Harkonen) Pär-Erik Levlin Cover Image Sauna Mauno Mannelin Historical Photo Collection Finnish Heritage Agency Additional copies are available for purchase at $10.00 per copy.

Photo by member Jane Ely.

Children in front of a storage building. Photo by Valter W. Forsblom, 1914, Southeastern Ostrobothnian Commonwealth Buildings Collection, Society for Swedish Litterature in Finland.

From the Editor | Issue 3

With a general theme of Finland Builds our volunteer team has come together to present the third quarterly edition. From log cabins, saunas, churches, bridges, and other monuments we see the talent and tools our Swede-Finn forefathers brought to their new homeland. Today their inspiration and influence extends around the world.

My own great-great grandfather, Mathias Karjenaho Abrahamson, was one of the first Finnish pioneers to arrive in 1865 and file his homestead in the area of Minnesota known as the Big Woods. Today, the Cokato Finnish American Historical Society preserves some of the traditionally built pioneer buildings at the Finnish Pioneer Park at Temperance Corner in Cokato, Wright County, Minnesota. My second great-grandfather’s name appears on the memorial plaque at the park, and

I have wondered if he helped construct the church or perhaps the savu sauna located there.

As we work to bring these quarterly publications to our membership, we build and deepen our understanding of our heritage. Our team is planning for 2023 and seeking topics or themes that we can begin to research. We are looking for stories from our readers, stories about your families that will help build a connection from the past to the present, traditions or customs that are part of your Finnish culture. Your ideas and requests will help us build our content framework. Please send your thoughts and ideas for future issues to info@swedishfinnhistoricalsociety.org. As we enter this new year the Kusiner team wishes you all, peace and joy.

Cassie Chronic, Editor

2

Photo by Valter W. Forsblom, 1914, Southeastern Ostrobothnian Outbuildings, Collection, Society for Swedish Litterature in Finland.

From the Director | Issue 3

I always enjoy the hopefulness that blankets the the world for a few days at the start of a new year. Suddenly everything is possible again.

Finnish emigrants must have been very hopeful when they bought land in their new country. It also must have been comforting to build something familiar while surrounded by the unfamiliar. Certainly, architects Gesellius, Lindgren, and Saarinen were inspired by the potential of Finland when they designed The National Museum of Finland—a museum that was completed seven years before Finland’s independence. Possibility gives birth to hope.

This issue features photos from an optimistic expedition to catalog the spirit of Finland by cataloguing the details of outbuildings in South-

ern Ostrobothnia. It is the glimpses of personality that I found the most interesting. A young woman, making a familiar frozen expression of someone that has found themselves in front of a camera is a stranger to us. Yet, we also know from her expression that she is not opposed to being photographed. I can see her shyness and a bit of giddiness. She overcomes shyness for the possibility of a photograph.

Like our ancestors, I am also hopeful. This year holds so much possibility for The Swedish Finn Historical Society and our members. But that is for the next issue.

Gott nyyt år! Kim

3

Illustrations by Hilding Ekelund, 1914, Southeastern Ostrobothnian Outbuildings, Collection, Society for Swedish Litterature in Finland.

4

Architects Armas Lindgren, Eliel Saarinen, Albertina Östman, & Herman Gesellius, Helsingfors, 1890s. Photo by C.P. Dyrendal. Historical Photo Collection, Finnish Heritage Agency.

National Museum of Finland completed in 1910. Photo by Heikki Havas. Finland’s Architecture Museum.

A Brief History of the Art Nouveau Movement in Finland

by Iona Hillman

by Iona Hillman

Art Nouveau was an international art movement popularized by artists during the late 19th and early 20th century as a reaction to the domination of neoclassicism in academic art. In Finland, this movement developed alongside Kansallisromantiikka (romantic nationalism)—or Jugend. During a period of conflict under Russian imperialism, the struggle for independence and a desire for a unifying national identity gave rise to a new, modern style of art and architecture.

Taking inspiration from the Kalevala, artists and architects utilized traditional Finnish motifs and themes to address the growing crises of political and social identity. The fusion of Finnish medieval features with international influences from surrounding European countries allowed for the movement to be a catalyst for the rise of romantic nationalism. The movement aimed to reestablish Finnish heritage and culture while simultaneously progressing into a modern age of economic growth, prosperity, and independence

Gesellius, Lindgren, Saarinen

At the height of the Art Nouveau movement, three Finnish architects – Herman Gesellius, Armas Lindgren, and Eliel Saarinen – founded an architectural firm that would oversee the development of Finland’s most important buildings in the early 20th century. After establishing their firm in 1896, Gesellius, Lindgren, and Saarinen took on numerous projects including the construction of the Helsinki Central railway station, the National Museum of Finland, Hvitträsk, and the Finnish pavilion at the Paris 1900 World Fair. Drawing inspiration from the National Romantic style and Art Nouveau trends, the three architects built monuments reminiscent of Finnish medieval architecture and the British Gothic Revival.

Ceiling fresco in the dining room of Hvitträsk.

Photo

5

by Soile Tirilä. Historical Photo Collection, Finnish Heritage Agency.

Vernacular Finnish Log Construction in America

by Frank Harkonen Eld

by Frank Harkonen Eld

Most Americans have a fascination of log cabins. It’s almost a romantic relationship. Many people pine (no pun intended) to live in a log cabin in the woods—their dream house! For some, cabins symbolize the rugged frontier. But, whatever the appeal, how often does anyone give any thought to where, or how, the American log cabin originated? Just as they did the sauna, it was the Finns who introduced the log cabin to the landscape. The Forest Finns in the New Sweden Colony built the first log cabins and saunas in America. Since then, the log cabin has become an icon of the American frontier, wherever it might be. The sauna and the log cabin are the Finnish legacy.

Years of extensive travel and research within the Finnish communities of the United States and Canada have demonstrated that these early emigrants brought with them, from Finland, a distinctive style of vernacular log construction. These craftsmen utilized the same unique building techniques everywhere they settled, with the exception of New Finland, Canada. Whether it was the first Forest Finns who arrived in America in the 1630s or those Finns (and other Nordics) who were a part of the “great migration” of the 1900s, they practiced a style of building that was unlike that of other nationalities. Finnish log building required a learned skill. It is a craft no longer practiced—a lost art.

6

Figure 1. Mortenson house in Pennsylvania.

Few examples of New Sweden era cabins exist. However, a small vestige of this legacy still remains, including the Mortenson cabin, in Pennsylvania, built by an ancestor of John Morton, a signer of the Declaration of Independence. See fig. 1.

For the next two hundred years since the introduction of the log cabin in New Sweden, multiple nationalities constructed varying types of log houses and buildings when they migrated into the American frontier. Even in 1890s, if you didn’t settle in a densely populated urban area, most everywhere else in upper United States was still the wilderness! Just as the other groups, when the Finnish immigrants came they, like the others before them, built cabins and farm buildings, but they also built saunas wherever they settled. None could be classified as dream houses! Most initial cabin were only one or two rooms. They were necessary shelters built with materials at hand. But the log buildings of the Finns (and other Nordics) were different from those built by other groups.

When the Finns arrived, they had to find work as most had little money. While some stayed in the populated east and worked in cities, small town mills, and stone quarries, most scattered to the remote frontiers of the northern Midwest and the western regions, settling near other Finns. These Finns did whatever they had to, to make a living.

Many worked in the mines while others labored in the timber industry. However, as soon as possible, most followed the dream of owning land. After a century of famine, starvation, and being displaced from their lands in Finland, they were determined to have a place of their own. They knew if they owned land they would not starve to death, as many had in Finland. Even a small parcel allowed one to raise food and meat. Most immigrants came from rural Finland and many had been tenant farmers, or crofters, with no opportunity to own land. In America, they could realize the dream of a place of their own.

In America’s remote frontier, Finns acquired their land by either homesteading or by buying cut over, “stump land” from lumber companies. These homesteads were often subsistence farms. Most Finns never made their living from these lands but worked other jobs. For example, my father was a carpenter, my maternal grandfather owned a small mill. Both homesteaded in a Finnish community in Idaho. In Ishpemming, Minnesota, these farmsteads were referred to as “mine farms”, because their owners worked in the mines. After they acquired their land, the Finns set about building their log structures. Usually all the buildings on these frontier farmsteads were built of logs from the property, using centuries-old log building techniques learned in Finland. Many remaining farms still contain original log saunas,

7

Figure 2. Kangas homestead near Embarass, Minnesota.

cabins, or barns. See figures 2–3.

Preparing the Cabin Logs

The homesteader’s first task was to clear the land for planting. The trees from this process were harvested to build the log structures. The logs were worked while they were green (recently cut), as they were much easier to hew (square) into building logs. Although logs were often left round when they were used in hay or livestock sheds, Finns typically squared the logs for heated buildings like cabins and saunas. These logs were debarked, marked with a string line, scored with an axe, and then hewed on both sides to a thickness of six inches (figure 4). Squared logs were longer lasting as they shed rainwater and exposed the more durable heartwood. The logs in traditional American log buildings commonly remained round as this required less labor and skill to construct. A marked exception to this was the German settlers, who also squared their logs.

Figure 4. Squaring the log.

8

Figure 3. Kaanta homestead near Palo, Minnesota.

Cabin Construction

In traditional early American log construction, logs were horizontally stacked and the corners locked together using saddle notching, or in some cases, dovetail notches. Large gaps (interstices) remained between the logs and had to be sealed with daubing and chinking (figure 5). This was a fairly simple process that required little experience. Most log cabin construction in America reflects these techniques. The Finns however, did not leave gaps between their logs as they stacked them. They fitted their logs tightly together. This was accomplished by scribing the profile of the lower log onto the log directly above with a

unique, handforged tool,the vara (figure 6). The upper, scribed log was then hewed to match the lower log’s profile, while at the same time, creating a channel to fit tightly over the lower log (figure 7). This technique of scribing and fitting by the Finns eliminated the use of chinking (figure 8). They used a double notch or a double dovetail (or some variation) to lock the corners together (figure 9). It was a learned skill. Since this building technique was much more difficult and time consuming than the easier “stack and chink” method of other builders, why did the Finns do it?

9

Figure 5. German cabin with chinking.

Figure 6. Scribing logs with a vara.

Figure 7. Hewing the channel.

Figure 8. Fitted logs.

Figure 9. Double notch corner notching.

Figure 10. Double dovetail corner notching.

Centuries of experience in log building taught the Finns that chinking will deteriorate and fall out over time and, therefore, must be maintained. So the Finns eliminated it. As the Finns stacked their carefully scribed and fitted logs together, they placed moss between the logs to prevent air infiltration.

It is what one does not see that distinguishes a Finnish cabin from a traditional log cabin. You see no chinking. Also, this is how it was explained by Bill Axe, the last Finnish axemen in Idaho. When he was asked how one would know if a cabin was Finnish built, he replied, “If you stand inside on a sunny day and look at the logs and no light shows through, it was probably built by a Finn!”

It is extremely rare to find any chinking in Finnish log construction. If it was used, it usually indicates the building was a temporary structure, or

built under time constraints, or the builder simply lacked experience in Finnish building techniques. One notable exception is found in New Finland, Canada, where no suitably straight or sufficiently large trees were available for scribing and fitting so they were forced to use chinking. However, the builders covered the logs with siding as quickly as possible

In New England, it was different for the Finns. Most went to work in the mills and quarries and lived in town. But when it became possible, many of these Finns also acquired land. They bought abandoned Yankee farmsteads to have a place of their own. They did not need to build log houses or barns because these farms already had buildings intact. But the Finns built one more building, a sauna. Many of these were built of log using the same Finnish building techniques, although

10

Figure 11. Rhode Island sauna.

sometimes large and straight trees were no longer available as seen in figure 11. This sauna exemplifies “sisu” and skill. This Rhode Island Finn, determined to have a sauna like in the “old country,” with scribed and fitted logs, used the material he had available!

Today, many examples of Finnish log construction remain, scattered throughout communities throughout America where they Finns built their farmsteads. Some in various stages of disrepair while others, preserved by historical museums and individuals who cherish this Finnish legacy, stand as monuments to the skill, sisu, and unique craftsmanship of these early Finns who introduced the log cabin and sauna to the American landscape (figure 11).

About the Author

Frank Eld, pictured below, is the author of Finnish Log Construction—The Art. He is one of the founders of the Long Valley Preservation Society. Today the society governs Historic Roseberry, Idaho. The townsite has twenty restored historic buildings that include a schoolhouse, a general store, and a museum. During the summer, Frank crosses the continent in his “Finnebago” researching and restoring historic Finnish buildings.

11

Figure 12. Outstanding example of Finnish log construction in Minnesota.

Replot Bridge | Replotbron

by Nancy Nygård

Growing up in the Pacific Northwest, near many bodies of water, I have seen and traveled over many types and styles of bridges. During my first trip to Finland in 2019, on The Swedish Finn Historical Society Heritage Tour, the importance of travel and the evolution of Finnish bridges was readily apparent. From the sixteenth century, when people walked or rode horseback between population centers, landowners provided crossings over bogs and small bodies of water by building causeways or crossings of piled stones.

With the abundance of timber, wooden bridges began to appear over rivers and smaller lakes. However, by the eighteenth century, the development of vaulting techniques, and improved masonry skills saw the construction of stone bridges. Many of these survive today and we crossed them during our travels in 2019. However, the bridge that made the biggest impact on me was the gorgeous modern cable-stayed tuftform bridge that connects the island of Replot with Finland’s mainland.

Arguably, one of the most beautiful bridges in Finland, the

Replot Bridge is 3,428 feet (1,045 meters) long. Olavi Knihtila was the architect for the bridge which opened August 27, 1997. The cable-stay bridge style is a cost effective choice to span distances between 800 and 300 feet. When the span is shorter or longer, a different bridge style makes a better choice.

The cable-stay style was originally introduced by the Venetian architect, Fausto Veranzio in 1595. It didn’t catch on quickly. The Truss and Suspension bridge style continued to be the favored style for the next three to four centuries. The popularity of

12

View of the Replot Bridge in Korsholm, Finland from Fjärdskäret skerry. Photo by BEF. CC BY-SA 3.0, 2008.

the cable-stay style wasn’t helped when two cable-stay bridges built in the early 1800s in Europe (Scotland and Germany) collapsed with disastrous results to human life. However, with modifications (stronger steel and improved tension in the cables) a cable-stayed bridge was successfully built in Ströms and, Jämtland, Sweden in 1955. Since that time, especially in the last thirty years, with the aid of advanced computer technology, the cable-stay bridge has become the bridge of choice for American architects and engineers. The US currently has over forty cable-stay bridges and plans in the works for many more.

In the cable-stay style, the bridge covers a greater distance than the truss and suspension style. The load (weight of the deck) is supported through the cable directly to the tower as opposed to the load being supported by vertical cables between larger cables that run between towers. The diagonal positioning of the cables offers a more open, aesthetically pleasing look of the bridge and its surroundings.

Sources: Tejada, John. About Cable-Stayed Bridges; Why this Bridge is Suddenly Everywhere, English. YouTube video, 8:07, accessed September 13, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W8_ wRcGUud4.

Replot Bridge, Wikipedia, accessed September 27, 2022. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Replot_ Bridge.

Björkstrand, Daniel. Amazing Finland, Replot Bridge, YouTube, 3:46, accessed September 13, 2022. https://youtu.be/CPPYb5Oeo28.

Finn Days. Driving Over the Most Beautiful Bridge in Finland. Replot bridge, Near Vaasa, YouTube video, 3:22, accessed September 13, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TD2yY92rVjU.

13

capturing the uncorrupted

by Kimberly Jacobs

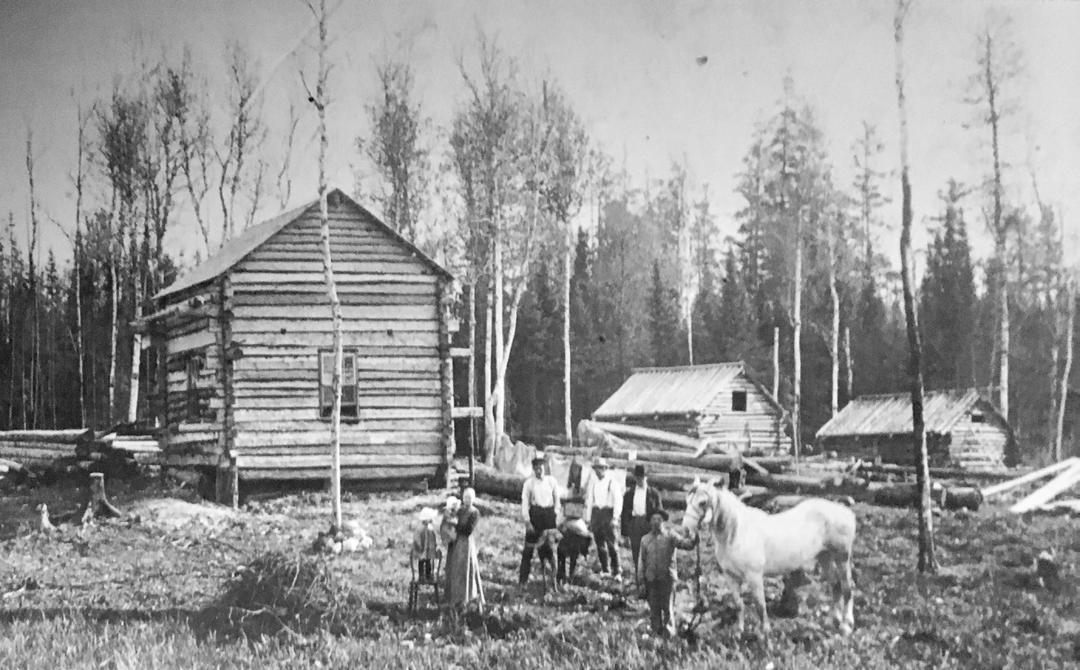

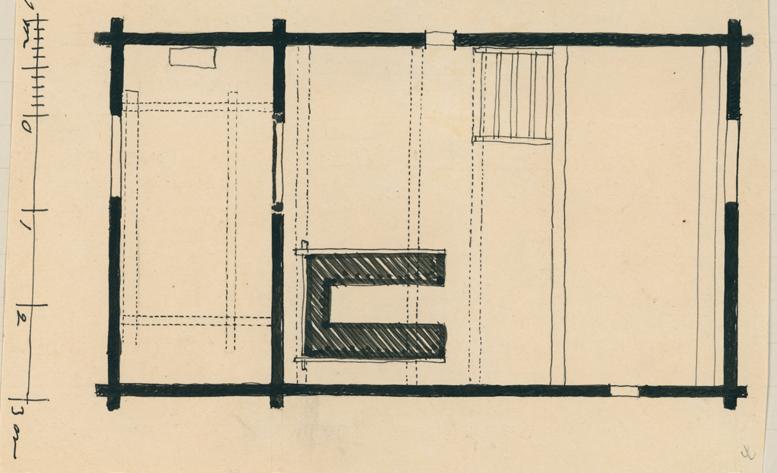

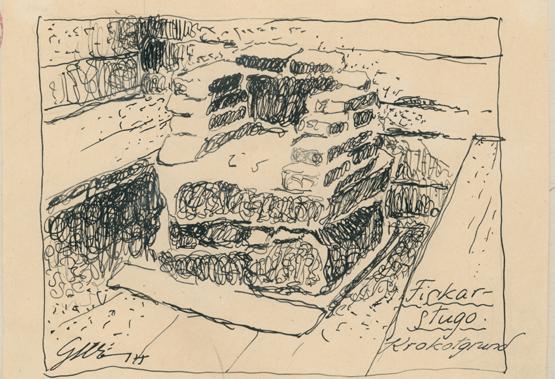

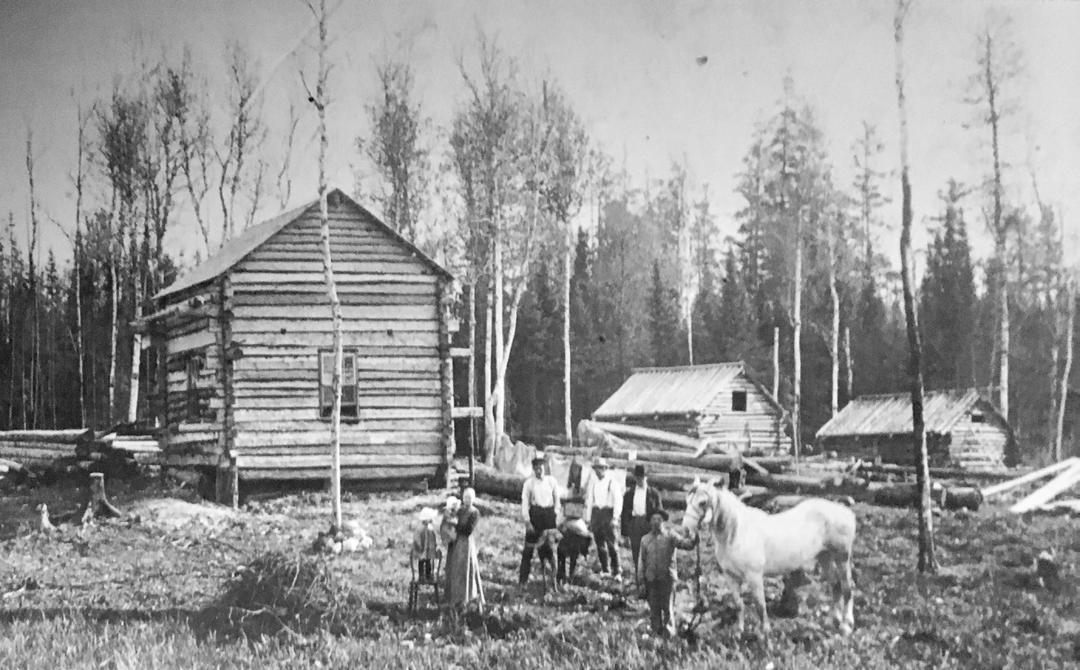

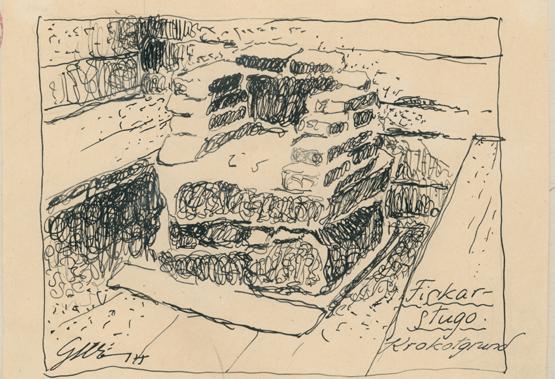

Photo essay features photographs by Valter W. Forsblom and illustrations by Hilding Ekelund. All of these images are part of the Southern Ostrobothnian Rural Buildings Collection of the Swedish Literature Society in Finland.

Previous page: Sauna of Josef Henrik Skogman-Gammelsved Right: Sauna floorplan.

Above: Lillstulänga of Josef Henrik Skogman-Gammelsved Right: Floorplan of Lillstulänga Lower righ:t Otpposite side of the Lillstulänga.

16

Josef Henrik Skogman-Gammelsved, Ömossa, Sideby

In 1914, the Swedish Literature Society in Finland sent its first ethnographic expedition to southern Ostrobothnia. Lead by Valter W. Forsblom, the ethnographers documented the houses and building of everyday Ostrobothnians. Students from the University of Technology drafted floorplans and cross-sections.

Architecture student, Hilding Ekelund, drafted and sketched many of the images from this expedition. Later he became a prominent architect. Like Ekelund, Finland’s most respected artists had long studied and idealized the common folk. Zacharias Topelius wrote on ancient Finnish wedding customs for his doctoral

Karl Storlås, Lålby, Lappfjärd

dissertation. In the 1890s, Akseli Gallen-Kallela documented folk art and architecture in eastern Finland. Both Gallen-Kallela and Jean Sibelius drew artistic inspiration from the Kalevala, itself a product of the ethnographic collection of Finnish folktales. They held the idea that the soul of Finland was carried in the pure traditions of the uncorrupted peasantry.

Romantic nationalism had influenced the arts and sciences in Finland since the first half of the nineteenth century, when the concept of independent Finland was new. At the time of the expedition, Finland had lost much of their autonomy and independence was on the minds of many. Independence would create Finnish nationality. But in a multicultural and multilingual nation, what would that mean? Thus, ethnographers felt an imperative to document and preserve folk culture—the authentic source of Finnishness.

Left: Outbuilding of of Karl Storlås in Lålby, Lappfjärd.

Right: Detail of outbuilding of Karl Storlås.

Soures Leerssen, Joep, ed. 2018. Encyclopedia of Romantic Nationalism in Europe. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. https:// ernie.uva.nl/viewer.p/21

Lönnqvist, Bo. 1991. Folkkulturens skepnader till folkdräktens genealogi, Series III, Volume 2. Helsingfors: Svenska Folkskolans Vänner.

Rosenström, Marika. “Det digitaliserade folklivet på Finna.” Svenska Litteratursällskapet i Finland, December 3, 2018. Accessed December 1, 2022. https://www.sls.fi/sv/blogg/det-digitaliserade-folklivet-pa-finna

Images: SLS 235 Sydösterbottniska allmogebyggnader collection, Svenska Litteratursällskapet i Finland. Photos by Valter W. Forsblom. Illustrations by Hilding Ekelund.

17

18

Outbuilding of of Alfred Pellfolk, Tjöck, Kristinestad.

19

Alfred Pellfolk, Tjöck, Kristinestad

Above: Farm courtyard of of Alfred Pellfolk, Tjöck, Kristinestad.

Below: Floorplan of outbuildings. The note, “Skala!” indicates Hilding forgot to include the scale of his illustration.

Opposite page

Top left: Floorplan of fishing cabin.

Middle left: Detail drawing of the fireplace in fishing cabin.

Top right: Cross section of fishing cabin.

Bottom: Josef Henrik Häggkvist’s fishing cabin in Sideby. The barefoot young man wearing a student cap is thought to be Hilding Ekelund.

Alfred Pellfolk, Tjöck, Kristinestad

Alfred Pellfolk, Tjöck, Kristinestad

Josef Henrik Häggqvist’s Fishing Stuga, Sideby

Josef Henrik Häggqvist’s Fishing Stuga, Sideby

John Hellund and His Swedish Finn Church

by Hannah Kourujärvi

On July 29, 1906, seven men and their families met to discuss the need for a church for the Swedish Finn community in Seattle. They were John Hellund, Frank Lillquist, Henry Lillsjö, Alex Jackson, John Sirén, John Lillquist, and Alex Koll. They collected $50.75 and $45.00 was pledged.

The first worship service was held on September 16, 1906, at Sveaborg Hall in Seattle. By Decem-

ber 16, 1906, the name Evangelisk Lutherska Svensk-Finska Församlingen was adopted. In 1923, the name of the church was changed to Emmaus Evangelical Lutheran Church. In 1910, they started construction of their church, with land donated by Henry Lillsjö, and building materials donated by the community. Frank Lillquist was treasurer, and Alex Koll, secretary. John Hellund, was made chairman.

22

Swedish Finn Historical Society Emmaus Lutheran Photo Collection

John Hellund, born as Johannes in 1869, in Pedersöre. He emigrated to the United States in 1886. John married Greta Sofia Gers on March 1, 1890. According to Johanna Padie, Swedish Finn Historical Society board member and granddaughter of John and Greta, they both went to the same church back in Finland, but had not met each other until living in Brooklyn. They owned a grocery store in Brooklyn until 1905, when they sold it. With their five children in tow, they took the train to Seattle.

John invested his money in property. In 1910, he built his family home in Ballard which is still standing today. John worked as a carpenter for the Finnish builder A. W. Quist, who was also contracted to build the historic Medical Dental Building in downtown Seattle. At the time of its completion, the Medical Dental Building was the third tallest building in the world, to be built with reinforced concrete. A. W. Quist also agreed to help build the Swedish Finn Church.

23

Top left, top right, bottom left: Ruth Stold and Wesley Gregor wedding at Emmaus Lutheran Church, 1954. Above: John Hellund. Photos from Hellund Family Collection, courtesy of Lori Lind.

Johanna Padie wrote in her family history that John worked as a carpenter for the church and built the center dome. “Services were held downstairs until the upstairs was finished.” Johanna’s family lore is that John initially started the congregation at his house because “he had five daughters and a pump organ.” John’s daughter Ellen is quoted in Johanna’s family history saying “Papa got people together saying that we must build a church for all these people.” Though Johanna Padie admits she doesn’t know how much is true or just family myth.

John was known for being a community leader, and a counsel to the Swedish Finn community of Seattle. He was the man a recent Finnish emigrant could talk to if they needed a job. Johanna was five years old when her grandpa John died on May 20, 1940, a few months after his 50th wedding anniversary, which was celebrated at Emmaus. She remembers him as a kind and gentle man. John’s funeral was held at Emmaus Lutheran Church and he is buried at Pacific Lutheran Cemetery.

Johanna has many fond memories of Emmaus. In fact, her very first kiss was in the church’s kitchen. Johanna remembers “sitting in the pews

24

as a young child,

Emmaus Lutheran 1923 confirmation class. John’s daughter, Edna, is in front row, third from left. Swedish Finn Historical Society Emmaus Lutheran Photo Collection.

and looking up at the coved blue ceiling and thinking it must be heaven.”

In 1967, the Emmaus congregation joined with the Lutheran church founded by Danish Americans, St. John’s. Combined, they dropped the “s” and became St. John Lutheran. The Emmaus congregation sold their building, and it was used as an Assyrian Orthodox church until recently. In 2020, Johanna was able to tour the building that was once Emmaus Lutheran Church during renovations to convert it into a single family home. Johanna said “[I was] looking at the studs and walls of the original structure and thinking ‘my grandfather built this.’” The Swedish Finn Historical Society reached out to the architect in charge of the renovations, who assured us they are preserving many of the original details.

Sources:

Padie, Johanna. Emmaus Lutheran Church Questions, October 25, 2022

Padie, Johanna. “Written Memories of Johanna Padie.” Seattle, Washington, n.d

Evangelisk Lutherska Svensk-Finska Församlingen Record Book Collection. Seattle, Washington, 1906. Swedish Finn Historical Society Archive.

Tanner Andrews, Mildred. National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: Medical Dental Building (Report). National Park Service. October 10, 2005.

25

Emmaus Lutheran 1949 confirmation class. SFHS Volunteer Verna Eriks second from the left. Swedish Finn Historical Society Emmaus Lutheran Photo Collection.

How Our Ancestors Lived

by Par-Erik Levlin

Originally published in Medlemsblad för Levälä Släktförening, No. 11, March, 1989. Reprinted with permission from Levälä Family Association.

In genealogical books you will mostly find only short dates about our ancestors’ births, marriages, and deaths, but not what it means to be a farmer in those days. To know that, you have to read history, and I don’t know how easy it may be in the U.S.A. to find books about the history of Finland and Sweden. I think you might find the book by the author Wilhelm Moberg, A History of the Swedish People, and I think you all know his novel series about emigration to the U.S.A., The Emigrants, Unto a Good Land, The Settlers, and Last Letter Home. But the conditions varied from district to district. I will try to describe how they were in Ostrobothnia far back in time.

People settled there very long ago. As early as in the Stone Age hunters wandered along the shore, and from the Bronze Age, 4000 years ago, we have plenty of ancient monuments. Through pollen analysis on samples from our peatbogs, scientists have proved that grain was grown there at the time of the birth of Christ. Cattlebreeding is even older, but hunting and fishing were still much more important.

As we, in the middle of the sixteenth century through the taxpayers lists, get to know the settlements and also are able to trace some of our ancestors, we see that Ostrobothnia still had a coastal population. The foremost exception was the Kyro area inside Vasa. The villages were small. Most of the farms were spread out with no close neighbour. In what at present is the Nykarleby area, at that time the village of Lepu, we had seventy farms along the Nykarleby River. Others

26

Seal boat, Replot, 1926. Ethnology Photo Collection, Finnish Heritage Society.

were spread out into the coastal villages of Munsala and Socklot. Higher up along the river you have to go to what now is Harma to find settlers from the Kyro area.

On the farms several generations lived together. The taxpayers’ lists mentioned only the husband by name. He usually paid personal taxes for five to ten persons of working age (fifteen to sixteen years old). As there were also children and old people on the farm, this number had to be at least doubled to get the real population number. As they, on Levala, paid taxes for thirteen persons, there must have been a lot more people on the farm. The areas on each farm, which were cultivatedted with barley or rye, were small, only six to ten acres. As they then normally gave only three and one-half times grain, they had to buy large amounts of bread grain. Besides grain nothing else was grown except turnips, but for these they didn’t have to pay tax.

The cultivation of corn was necessitated by cattlebreeding, without the dung from the cattle, the fields didn’t give any crops. The access to dung was consequently a limiting factor for agriculture. The livestock consisted foremostly of cows and sheep. Goats were not so common in Ostrobothnia. For working and transport they had horses. The number of animals were limited by access to cattle food for the winters. They got the feed from the meadows and the sea and lakeshores, marshes, or wherever they could find something. They also used leafy branches and straw.

In Lepu village (now Nykarleby) the farms were placed near the river. The fields were also near rivers. Among the fields and forests were meadows. The meadows were also a part of the cultural landscape, as they were made through clearing the forest and had been kept open with axe and scythe. The meadows, however, were not com-

27

Seal hunters towing boat onto the ice, Replot, date unknown. Ethnology Photo Collection, Finnish Heritage Society.

pletely free from trees. There were birches and alders left in about six yards intervals. They shaded the ground and kept it wet. They also fertilized it with their leaves. The fields and meadows were fenced off from the forest. In summer, the cattle grazed in the forest and had to be kept out of the meadows. After fields and meadows were harvested, cattle were let in.

The cows gave milk only in the summertime and from the milk butter was made. In the fall they had to slaughter the part of the cattle they could not feed during winter. In that time the cows were very small, only three hundred to four hundred pounds, and they gave only three hundred quarts of milk in a year.

The fishing was almost as important as farming. Even farms far from the shore had fishing waters in the sea. Creeks and rivers were rich in fish, and salmon fishing was good. We can compare them with the streams in Alaska today. The best fishing was in the spring as the fish spawn. In the spring tons of herring were caught. They were salted in barrels or dried. As salt was very costly, even a third method of preservation was invented. The herring was put in barrels, one portion herring to one portion of salt. The barrels were closed airtight. The herring turned sour and was preserved as sour herring. Even today it is regarded as a great delicacy in northern Sweden.

The seal catch was the only thing of importance as far as hunting was concerned. In March, all the men from the villages, divided into groups of eight to ten, went out on the ice of the Gulf of Bothnia dragging a boat. The boat was covered with the sail and at night used as a camping site and to save them if the ice broke up. From there they made daily hunting tours. Before they had firearms, the seal was hunted with harpoons, the hunter had to get close. The most important part of the seal was the lard, from which they bolied seal oil. It was sold as lamp oil all over Europe, but meat and skins were also used. The hunting tour ended in the beginning of June, and usually every hunter had gotten two to three barrels of oil.

In the forest, near the shore of Ostrobothnia there was not much to hunt. Of fur, only squirrel skins or gray skins were exported. The elk was already so rare in the seventeenth century that the government limited its hunting.

Not until the seventeenth century did wood gain value for its products. Earlier, people could get timber for building houses everywhere. But during the end of the sixteenth century, the woods in Europe began to diminish. Sawmills were built in Sweden and Finland but even more important was the production of tar, The procedure was known as far back as the Middle Ages and was produced everywhere for private use. Then it was produced for export. The manufacturing created lots of employment. Young growing pines had to be barked from the ground to five yards up the trunk. This was repeated for several years until all the bark was gone. Doing so, the pines produced plenty of resin to protect themselves. One year after the last barking, the pines were cut and brought to a place with a tarpit where a stack was built. There the pine wood was covered, airtight, and burned with little air, so the resin was converted into tar. The tar ran out through a pipe in the bottom of the pit. The biggest production of tar in Sweden and Finland occurred in Ostrobothnia.

If we take a look at the farmer’s year in the seventeenth century, it may have begun after Christmas when one man was sent out in the forest to hunt squirrels with bow and arrow. Two others or a man and a woman went out to bark pines for tar production. Others stayed home producing barrels for storing salt fish and seal oil. In March, all healthy men went out seal hunting and when they went home in the first days of June, the fishing period began. The work in the fields was left for the women, young boys, and old men. The cattlebreeding was solely a job for women, as it has been up to our day. In July, the harvest of winter food for the cattle began and, in that, everyone on the farm took par.t So also in the harvest of crops in August and September. In the fall there was also threshing work and some fishing. In Novem-

28

ber, a man from the farm, in company with other villagers, went by boat to Stockholm to sell products from their farms. Thus, another hardworking year was gone and it was Christmas.

To complete this short essay, we can look at a list of what the Ostrobothnian farmers brought to Stockholm in the year 1556 in both quantity and value:

Product Quantity Value in marks

Salt herring 3,070 barrels 24,520

Butter 87,500 pounds 11,010

Seal oil 73,700 pounds 5,300 Dry fish 46,100 pounds 2,440

Salt salmon 345 bushels 2,000

Seal skins 2,870 pieces 540 Gray skins 670 pieces 70 Boats 54 pieces 810

Various 300 47,000

Source: Svenska Osterbottens historia. Printed in Wasa, 1977.

After duty was paid they had 40,000 marks left. But this was not all they produced for sale. Parts of their products were brought to Raumo, Åbo and some cities in Sweden. How big this part was we don’t know. Because their own grain crops, estimated in value to be 50,000 marks, covered only half of their need for bread grain, they had to buy the other half. They also had to buy large amounts of salt. They did not have much left over for the years crops failed.

About the Author Pär-Erik Levlin, 1920–2008, founded the Levälä Family Association in 1979. His research began with David Eriksson Leväla, born 1704, and his eight children born on the Levälä farm in Ytterjeppo, Nykarleby. The result was eight volumes of Levälä family history. They are available in The Swedish Finn Historical Society’s research library.

Stand of debarked trees being readied for tar production. Photo by Uuno Peltoniemi., Ethnology Photo Collection, Finnish Heritage Society.

29

Tarpit. Photo by I.K. Inha. Ethnology Photo Collection, Finnish Heritage Society.

Tools of the tar trade, 1936. Photo by Eino Mäskinen, Ethnology Photo Collection, Finnish Heritage Society.

Swedish Finn Historical Society

1920 Dexter Avenue North Seattle, WA 98109

Address Service Requested

Non-Profit org U.S. Postage Paid Seattle, WA Permit NO. 592

Swedish Finn Historical Society

Membership Application name address email phone number Membership Levels individual—$30.00 family—$40.00 lifetime—$500.00 senior/student—$25.00 patron—$50.00 business—$100.00

Kusiner Subscription Type printed copy mailed to home—$25.00 electronic copy—free with membership Membership Level $ Kusiner Type $ total enclosed $ signed mail to:

Swedish Finn Historical Society 1920 Dexter Avenue North Seattle, WA 98109 OR join online: www.swedishfinnhistoricalsociety.org

Membership renews on an annual basis in January. If new members join mid-year or later, the membership will extend through the following calendar year. An electronic subscription to our Kusiner publication is complementary with every membership and begins at the time of joining. If you wish to receive printed copies add $25 to cost of your annual membership.

Members in Europe can use this account to pay their dues: Aktia Bank Östra Centrum, Helsingfors.

Account number: 405500-1489157 IBAN number: FI9240550010489157 Bank BIC cose: HELSFIHH.

•••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••

by Iona Hillman

by Iona Hillman

by Frank Harkonen Eld

by Frank Harkonen Eld

Alfred Pellfolk, Tjöck, Kristinestad

Alfred Pellfolk, Tjöck, Kristinestad

Josef Henrik Häggqvist’s Fishing Stuga, Sideby

Josef Henrik Häggqvist’s Fishing Stuga, Sideby