28 minute read

DOC’S GUYS

In the late 1960s into the early 1970s, Doc Counsilman’s Indiana University swimming program was a focal point of the sport. His legendary teams were a dominant presence not just on the collegiate scene, but also on the national—and international—stage.

BY JOHN LOHN

Advertisement

Words were not necessary. All that was required was a glance around the natatorium. A look at the banners that celebrated past championships...A look at the honor roll of Olympians...The intensity and purpose that defined the workouts taking place in the pool...The concentration in the eyes of the coach monitoring the work that was underway.

When Doc Counsilman took the reins of the Indiana program in 1957, the Big Ten Conference belonged to Michigan and Ohio State. Within a few years, though, Counsilman shifted the balance of power to the Hoosier State, and that control endured for two decades, with Indiana also emerging as a major force at all levels of competition.

From 1961 to 1980, Counsilman led the Hoosiers to 20 consecutive Big Ten Conference crowns, and Bloomington, Ind. became a hub for top talent. Athlete after athlete—and team after team—passed along vast expectations in two departments. First, the Hoosiers were going to win, plain and simple. They were going to contend for championships and compete at an elite level. More, they were going to conduct themselves with class, and honor the traits of their coach—humility, dedication and loyalty.

NOBODY BETTER

dominated his sport than Doc Counsilman.”

The preceding quote was once uttered by legendary Indiana basketball coach Bob Knight, a man who shared a campus with Counsilman. While the two men were opposites—Knight’s explosiveness contrary to Counsilman’s serenity—there was an appreciation for the success each maintained. And, boy, did Counsilman excel in his profession!

Nothing matched what Indiana was able to conjure up during the height of the Counsilman era, defined as the mid-1960s into the mid-1970s.

At the 12 NCAA Championships held between 1964 and 1975, Indiana put together a sensational run that included six team titles and five runner-up finishes. During that stretch, the rivalry between Indiana and the University of Southern California (coached by another legend, Peter Daland) was second to none—regardless of the sport. Every year in which Indiana was the second-place finisher at the NCAA Champs, USC was the victor. Meanwhile, in four of Indiana’s championships, Southern Cal was the runner-up.

DYNASTIES AND RIVALRIES

What the University of Texas has done under the guidance of Eddie Reese is certainly worth mentioning in the same breath as Counsilman’s Indiana heyday. Since Reese arrived at Texas in 1979, he has led the Longhorns to 14 NCAA team titles (a record) and

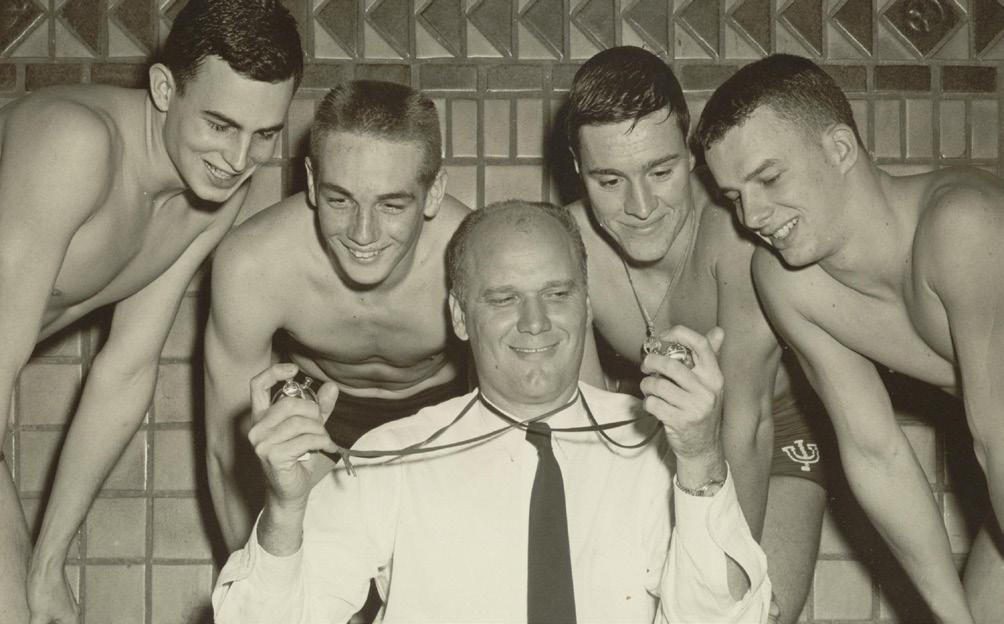

<< Dr. James E. “Doc” Counsilman started his coaching career at Indiana University in 1957. From 1961 to 1980, he led the Hoosiers to 20 consecutive Big Ten Conference crowns, and Bloomington, Ind. became a hub for top talent. On that 1961 team were (from left) Stan Hurt, Dick Beaver, Frank McKinney Jr. and Bill Barton. [PHOTO FROM SWIMMING WORLD ARCHIVES]

12 runner-up finishes. In the 41 NCAA Champs Texas has contested with Reese in command, the team has finished among the top three on 33 occasions.

Before both Counsilman and Reese, Robert Kiphuth had his own dynasty at Yale, where he compiled a 528-12 dualmeet record and won four NCAA titles between 1918-59. The Bulldogs added eight runner-up finishes at the NCAA Championships, and Kiphuth was known as an innovator through the implementation of interval training and dryland work that emphasized weightlifting.

No, swimming is not a contact sport like football, where players from rival teams can physically punish one another through a crushing blow in the open field. Still, the rivalry between Indiana and USC >> In 1968, Counsilman’s Hoosiers won the first of six straight NCAA team championships, a record that has not been matched. That same year in Mexico City, IU swimmers (from left) Don McKenzie (2), Mark Spitz (2) and Charlie Hickcox (3) went home with seven Olympic gold medals among them. Of course, four years later in Munich, Spitz was fierce. captured that many gold medals all by himself! [PHOTO PROVIDED BY INTERNATIONAL SWIMMING HALL OF FAME]

“I wouldn’t say there was hatred. That might be a little too strong,” said Gary Hall Sr., a three-time Olympian who competed individual medley at the 1968 Olympics, where he also picked up a collegiately for Indiana. “But we didn’t like one another. That silver medal in the 100 backstroke and added another gold medal in wasn’t a mystery.” the 400 medley relay.

The truth is, Indiana could easily have captured its first NCAA Also hailing from Indiana’s most-dominant days were individual team title in the early 1960s. Fueled by Hall of Famers Chet Olympic titlists Don McKenzie (100 breaststroke) and Jim Jastremski, Mike Troy, Ted Stickles and Kevin Berry, the Hoosiers Montgomery (100 freestyle), with Mike Stamm (100 backstroke/200 were loaded, and had little difficulty reigning atop the Big Ten backstroke) and John Kinsella (1500 freestyle) capturing Conference. However, due to infractions by the football team, all silver medals. Indiana teams were barred from NCAA championship contention from 1960 to 1963. ALWAYS STRIVING FOR SUCCESS

STACKED WITH TALENT

Finally, in 1968, the breakthrough came for Counsilman’s program, as the Hoosiers raced away from their NCAA counterparts. That championship marked the first of six straight titles, a record that has not been matched. As Indiana rolled through the opposition, it did so behind rosters that were stacked with talent.

Actually, calling these Indiana squads loaded would be an understatement. A fan of the program once quipped that Counsilman went to battle with an atomic bomb, compared to the water gun of his foes. Meanwhile, experts suggested that if Indiana had faced any country in the world in a dual meet, it would have prevailed.

The biggest weapon in the Indiana arsenal was undoubtedly Mark Spitz. The 11-time Olympic medalist, who is best known for his seven gold medals at the 1972 Games in Munich, flourished for the Hoosiers from 1969-72. Although Spitz rated as the world’s premier swimmer, he was treated like any other member of the Indiana roster.

“What Doc had was this great ability to make you feel like the most important person in the pool,” Spitz said. “Everyone came away with that feeling, whether he was a Mark Spitz or a walk-on.'”

Among the other standouts at Indiana during its heyday years were Hall and Charlie Hickcox. Hall was a world record holder in multiple events and medaled in three Olympiads (1968, 1972 and 1976). As for Hickcox, he won double-gold in the 200 and 400

Not surprisingly, the atmosphere at the Midwestern school was intense, team members pushing one another to reach their goals and to achieve the next significant milestone within their reach. The option to coast through a workout did not exist—not with teammates and not with Counsilman.

“When I got there, I knew the tradition was rich,” Hall said. “Everyone knew about the past, and that’s why they gave themselves to the program. There was an obligation to carry on the tradition by stepping up and doing your part. We came to be part of this family, and it was important to do whatever was needed to maintain a high level. Nothing less was accepted. Every day, we tried to one-up each other. We were all trying to get Doc’s attention.”

The trust the athletes had in Counsilman was immeasurable, and that faith came from two primary areas. More than anything, Counsilman’s track record spoke for itself, and his troops knew exactly what his leadership produced. As a complement, Counsilman was an innovator and unafraid to introduce new tactics and training methods.

Counsilman placed an emphasis on strength training and film analysis, and he frequently called his athletes into his office to analyze 16-millimeter film and study ways they could cut time. Counsilman also emphasized underwater filming and was known to place lights on the fingers, hands and arms of his swimmers and, with the natatorium lights shut off, use the lights to detect proper hand and arm entry into the water.

>> Including Counsilman and diving coach Hobie Billingsley, 15 swimmers/ divers/coaches from Indiana University have been inducted into the International Swimming Hall of Fame—with 11 swimmers having trained with Doc. (Pictured: Gary Hall Sr., Class of 1981, signs his honoree display at the Hall of Fame Museum in Fort Lauderdale, Fla.) [PHOTO PROVIDED BY INTERNATIONAL SWIMMING HALL OF FAME]

THE X-FACTOR: DOC

However, the Indiana program was not suffocating. Rather, it stressed accountability and taught the swimmers the importance of self-reliance and responsibility to others. This mentality was engrained in the Hoosiers and passed along from class to class.

“Great swimmers usually have an innate sense of how they function. They seem to know instinctively how hard they need to work and when they need to ease off,” Counsilman said. “There’s no need for the slave-driver approach to coaching. By respecting the swimmer’s perceptions about his swimming—and by good communication—a coach can develop the sensitivity to understand the swimmer’s basic needs.

“The great coach must have two basic abilities: He must be a good organizer and a good psychologist. The good organizer will have the large team, will attract the good swimmers from other teams, and develop (Mark Spitz) and (Gary Hall). The good psychologist will be able to handle the parent problems, get along with the city council and be able to communicate successfully with the swimmers. He will have the super teams.”

Outside of the pool, Indiana’s legendary teams were tight-knit, with a common gathering place the home of their coach. While Counsilman monitored his athletes’ academic progress and allowed the use of his personal office as a work or study center, his wife, Marge, played the role of team mom. Marge Counsilman often cooked meals for the Hoosiers and provided them with a comfort zone, especially those feeling homesickness.

The potential of an NCAA program, including top guns Texas and Cal-Berkeley, winning six consecutive team championships would be quite a challenge in the current era, due largely to greater depth from coast to coast. So, Indiana’s record is likely safe, the passing of time only adding to the legend of what Counsilman constructed.

“Doc was unusual in a lot of ways compared to others I’ve known in the sport,” Hall said. “He was intelligent and had incredible personality traits. He made everyone feel special, and that was a key with the superstars. He related to everyone on the team and spoke a vernacular that resonated with the guys on the team. He used his share of four-letter words, and he was funny. He showed such humility, and the team followed his example. It was an honor to be coached by him and to be part of that program.”

The ORIGINAL Resistance Swim Team Training Gear USED BY ATHLETES W O R L D W I D E

IN WATER RESISTANCE TRAINING GEAR

Increase stamina & speed | Quicker acceleration | Enhanced Endurance

NZCordz.com | 800.886.6621

FREE SHIPPING ON ALL ORDERS OVER $50

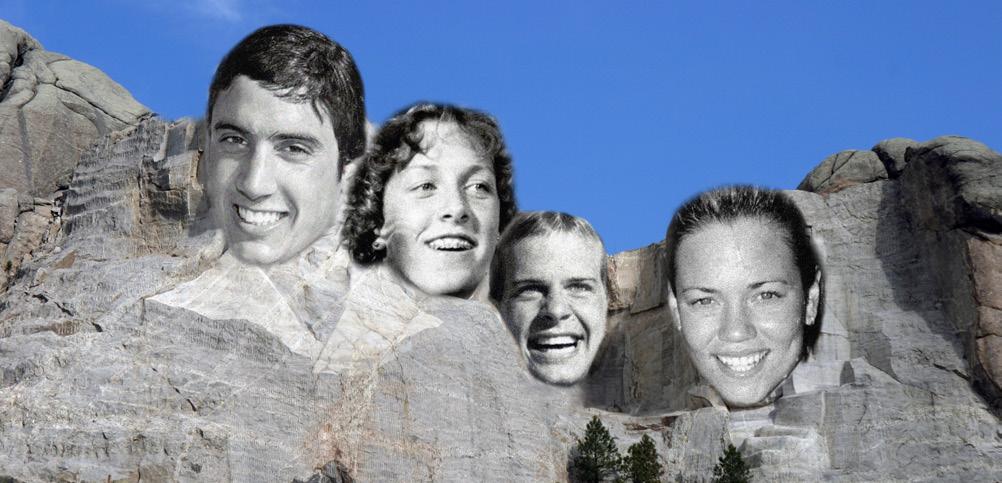

THE MOUNT RUSHMORE

OF NCAA DIVISION I SWIMMING

If there were a sculpture made of the top American NCAA Division I swimmers similar to the one depicting four U.S. Presidents on Mount Rushmore, Tracy Caulkins, Natalie Coughlin, Pablo Morales and John Naber would be worthy honorees. No other U.S. swimmer has won more NCAA D-I individual titles than those four.

BY ANDY ROSS

>> PICTURED ABOVE (FROM LEFT): PABLO MORALES, TRACY CAULKINS (PHOTO BY HORST MULLER), JOHN NABER (PHOTO BY BOB INGRAM) & NATALIE COUGHLIN (PHOTO BY TONY DUFFY) >> Tracy Caulkins was often referred to as one of the greatest female swimmers of all time, but she was only able to compete in one Olympics, where she won three gold medals. The U.S. boycott the Games in 1980, and Caulkins retired from the sport after the ’84 Games at the age of 21. [PHOTO BY USA SWIMMING/PROVIDED BY INTERNATIONAL SWIMMING HALL OF FAME]

TRACY CAULKINS, FLORIDA (12)

100 breast 1984; 100 fly 1982; 200 fly 1982-84; 100 IM 198283; 200 IM 1982-83-84; 400 IM 1982-83-84 (also swam on four winning relays)

Tracy Caulkins won 12 NCAA titles in her career at the University of Florida from 1982-84. But she was in a unique position compared to other swimmers who competed after her: Back then, swimmers weren’t limited to the number of individual events they could swim. That changed in 1987 when NCAA rules stated that swimmers would be limited to three individual events and four relays or two individuals and all five relays.

Then again, Caulkins only swam three years of college instead of four, forgoing her senior year and retiring after the 1984 Olympics in pursuit of completing her schooling—she earned her bachelor’s

degree in broadcasting in 1985.

As a freshman in 1982, she won five titles: 100 breast, 100 fly and all three IMs—100, 200 and 400. She also helped the Gators win the 400 medley relay en route to Florida winning the first championships ever held for NCAA Division I women.

In 1983, she added four more individual titles: the 200 fly plus another 100-200-400 IM sweep. Later that year, the NCAA coaches proposed changes to the championship meet format that would eliminate the 50s of strokes (excluding freestyle) and the 100 IM.

With her college/national/international success, Caulkins is still regarded today as one of the best American swimmers ever.

Her 400 yard IM American record of 4:04.63 set in 1981 lasted for 11 years until it was finally broken by Stanford’s Summer Sanders in 1992. And her 200 IM mark of 1:57.06 from 1984 lasted until Sanders broke it in 1991. Her times from the ’80s would still be competitive today...and she didn’t have the advantage of kneeskin techsuits, polyurethane caps or really any knowledge on underwater kicks.

NATALIE COUGHLIN, CAL (11)

100 back 2001-02-03-04; 200 back 2001-02-03; 100 fly 200102-03-04 (also swam on one winning relay)

Natalie Coughlin was near perfect in her NCAA career, winning 11 of a possible 12 NCAA individual titles in her four years at CalBerkeley from 2001-04. She won four titles in the 100 butterfly and 100 backstroke, and three in the 200 back.

In her freshman season, she secured two of her three wins over Olympic gold medalists. In the 100 yard fly, she upset Stanford’s Misty Hyman to set an NCAA record at 51.18. In the 100 back, she bested Hyman again and future Olympian Haley Cope for an American record of 51.23. In the 200 back, Coughlin bested 1996 Olympic gold medalist Beth Botsford of Arizona by four-and-a-half seconds to take nearly two seconds off the American record with a 1:51.02.

Her three NCAA records (she just missed Jenny Thompson’s 100 fly American mark of 51.07 set in 1998) landed her on the cover of Swimming World (May 2001) and launched herself as a household name. She had also been an excellent high school swimmer (SW’s Female High School Swimmer of the Year, 1998), but she took that next step in her rookie year of college.

The following year, 2002, was, perhaps, the best of her college career. As a sophomore, she destroyed the American record in the 100 fly, becoming the first woman to break 51 seconds and almost the first to break 50—a 50.01, which stood as the American record for 13 years. In the 100 back, she did break that magical 50-second barrier with a 49.97, which lasted as the American record for 15 years until 2017. On the last day of the meet, she set two more American standards: a 1:49.52 in the 200 back (which stood until 2009) and a 47.47 in the 100 free in leading off the 400 free relay.

Coughlin again won the 100 fly and both backstroke races in 2003, and in her senior year, she had a chance to finish her four-year college career by winning all 12 of her individual events. Despite a relatively disappointing showing on the two relays on Day 1, she bounced back with wins in the 100 fly and 100 back on Day 2. That left the all-important 200 back as her final hurdle.

This was before meets were streamed live online, so when ESPN2 televised its tape-delayed coverage of the 2004 NCAA Women’s Championships, it waited until the very end to show the 200 backstroke—even after the 400 free relay—to give its audience the opportunity to see whether or not Coughlin could make history.

In 2004 (and one other time in 2000), the events were held short course meters instead of yards. The 200 back was an event in which Coughlin held the world record...and Cal’s golden Golden Bear was under world-record pace at the 50, 100 and 150 (by nearly a full

>> Sixteen years after her college career at Cal, Natalie Coughlin was still competing at the age of 38, representing the DC Trident of the International Swimming League. [PHOTO BY MIKE LEWIS ]

second). But on the final 50, Coughlin struggled (“I couldn’t move my legs, I couldn’t kick,” she would say later). Auburn’s duo of Kirsty Coventry and Margaret Hoelzer both passed Coughlin, with Coventry (the eventual Olympic gold medalist in 2004 and 2008) touching in 2:03.86, the second-fastest 200 back in history.

Still, Coughlin finished her career with 11 individual victories, second only to Caulkins.

PABLO MORALES, STANFORD (11)

100 fly 1984-85-86-87; 200 fly 1984-85-86-87; 200 IM 198586-87 (also swam on three winning relays)

Stanford’s Pablo Morales is officially the winningest male swimmer in NCAA Division I history with 11 individual titles from 1984-87. John Naber had held that distinction after the 1977 season with 10 wins, but Morales passed him after taking Titles #9, 10 and 11 at the 1987 NCAAs at Texas.

He swept all four years of the 100 and 200 butterfly, and won three titles in the 200 IM during his sophomore, junior and senior seasons. However, as a freshman, Morales, swimming in his very first college championship finals, finished fourth in the medley (1:48.08), albeit only 13-hundredths off Ricardo Prado’s (SMU) winning time of 1:47.95.

Two days later at that 1984 meet, Morales held off Prado in the 200 butterfly (in which Prado was the defending champ) by 1-tenth of a second, 1:44.33 to 1:44.43. On the meet’s middle day, Morales clocked an American record in the 100 fly (47.02).

In 1985, Morales broke American records in both butterfly events, becoming the first man to break 47 seconds in the 100 (46.52) and the first to break 1:43 in the 200 (1:42.85). He also won the 200 IM in 1:46.08. 1986 was more of the same for Morales, who broke the American record again in the 100 with a 46.26 in prelims, taking the final in 46.37. His 200 IM inched closer to the American record of 1:45.08 with a 1:45.43, and his 200 fly (1:43.05) was just a couple tenths

Naber won the 100 against some stiff competition from Indiana (John Murphy, Mel Nash and Bill Schulte) in 49.94... but a day earlier, Naber became the first swimmer to break 50 seconds for 100 yards of backstroke with his 49.85 leadoff leg for the 400 medley relay. The 200 was a different story, as he won by 3-1/2 seconds with a 1:46.82—two seconds faster than his American record from the year before. His winning time was faster than the 200 yard butterfly American record for the first time in history. After starting his college career a perfect six-for-six, Naber tasted defeat for the first time in 1976 when Long Beach State >> Not only did Pablo Morales become the winningest NCAA Division I male swimmer in history with 11 individual titles, but he also was a member of five NCAA championship teams at Stanford—three in swimming (1985-87) and freshman Tim Shaw, the reigning 200-4001500 meter freestyle World champion, beat two in water polo (1985-86). [PHOTO BY TIM DAVIS PHOTOGRAPHY ] him in the 500. It was tabbed as the race of the meet, away from his own record (1:42.85, 1985). and it lived up to the hype. Shaw and Naber

As a senior in 1987, Morales needed two victories to tie Naber became the first two swimmers to go under 4:20, with Shaw coming as the winningest male swimmer in NCAA D-I history...and three out on top at 4:19.05 to Naber’s 4:19.71. wins to surpass him. That race almost repeated itself the next night when Naber held

The 200 IM on Night 1 was, perhaps, his toughest challenge. He off Cal freshman Peter Rocca in the 100 back final, 49.93 to 49.95. had been leading at each turn, under record pace through 150 yards. But in the 200 back, Naber put a bit more distance between himself But Texas’ Doug Gjertsen was charging hard on freestyle, and and soon-to-be Olympic teammate, winning in 1:46.95 to 1:48.09. Morales was hurting. Feeling the effects of a 21.9 butterfly split on A few months later, those two swimmers repeated their 1-2 finish the opening 50, Morales was still able to hold on to win in 1:45.42 in the 100 and 200 meter back at the 1976 Olympics in Montreal. to Gjertsen’s 1:45.82. He missed UCLA’s Bill Barrett’s American In his final NCAA meet in 1977, Naber (4x Olympic gold record (1:45.00, 1982) by less than a half-second...but the hard part medalist, 1976) and Shaw (400 free Olympic silver medalist, 1976) for Morales was over. met once again in the 500 free. Shaw won again, this time in 4:17.39

In the 100 fly, Morales, with a 46.47, also just missed his own (the third fastest time in history) to Naber’s 4:19.07. American record from a year before, but he solidified a 1-2-3 finish In the 100 back, Naber broke his own American record with a with Stanford teammates Jay Mortenson and Anthony Mosse, being 49.36 to win his fourth straight title in the event, then finished with the only swimmer to break 47 seconds. a 1:46.09 in the 200 back for another American record.

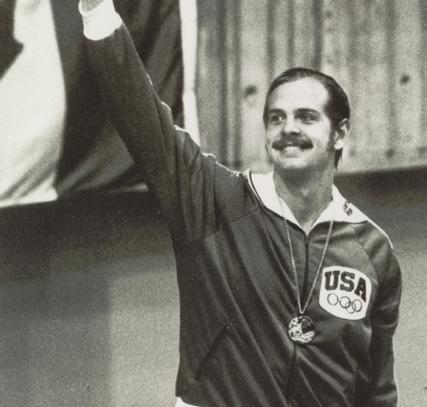

The final night in the 200 fly, Morales led from the outset and Besides all of his individual successes, Naber helped USC win was hardly challenged, winning with an American record of 1:42.60, four team titles all four years of his college career. ahead of Mosse at 1:44.25. It was a perfect ending for Morales, who had become the top male swimmer in college history with 11 NCAA individual titles. >> While John Naber was at USC, winning 10 individual titles and four team championships, he also competed at the 1976 Olympics in Montreal, where he won four gold medals—all in world-record time—and one silver medal. [PHOTO BY BOB INGRAM ]

JOHN NABER, USC (10)

500 free 1974-75; 100 back 1974-75-76-77; 200 back 197475-76-77 (also swam on five winning relays)

USC’s John Naber had held the record for most NCAA D-I individual titles for a decade after he won 10 from 1974-77, sweeping the 100 and 200 back all four years, as well as earning two wins in the 500 free.

As a freshman in 1974, Naber swam his first college championship final in the meet’s first race, the 500 free. All he did was upset Indiana’s John Kinsella, the American record holder (4:24.49), who was vying for his fourth consecutive title. Naber won in 4:26.85; Kinsella finished sixth in 4:33.69.

It was an auspicious start for the Trojans—and a not-so-welcome start for the Hoosiers. By meet’s end, USC beat Indiana by one point to put a halt to IU’s six-year winning streak.

Naber would go on to win the 100 and 200 backstrokes, both in American record time (50.51, 1:48.95), as the Trojans celebrated their first national title in eight years.

As a sophomore in 1975, Naber blasted an American record in the 500 free with a 4:20.45—more than six seconds faster than his winning time a year earlier. And he added two more American records in his specialty, the backstroke.

OLYMPIC RIVALRIES OF YESTERYEAR

BY JOHN LOHN | PHOTOS BY INTERNATIONAL SWIMMING HALL OF FAME

Rivalries have always defined the sport. Michael Phelps vs. Ian Crocker. Gary Hall Jr. vs. Alexander Popov. Shirley Babashoff vs. East Germany. These are just a few rivalries that stand out and should long be remembered.

But what about the rivalries from the early days of swimming?

Many of these duels have been forgotten, lost over time. As our “Takeoff to Tokyo” series continues, Swimming World takes a look at some of these rivalries from yesteryear.

ZOLTAN HALMAY vs. CHARLES DANIELS

As the Modern Olympics gained traction and grew in popularity, Hungary’s Zoltan Halmay and the United States’ Charles Daniels engaged in what can be considered the first true rivalry in the sport. On four occasions between the 1904, 1906 and 1908 Olympic Games, Halmay and Daniels produced gold-silver finishes, with each man winning a pair of titles.

Halmay got the early advantage on Daniels, winning the 50 freestyle and 100 freestyle at the 1904 Olympics in St. Louis, with Daniels claiming the silver medal in each event. Daniels, however, had the stronger overall Olympiad, thanks to victories in the 220 freestyle, 440 freestyle and in the lone relay contested.

On a head-to-head basis, Daniels took control of the rivalry at the 1906 Intercalated Games in Athens and the 1908 Olympic Games in London, where he prevailed in the 100 freestyle. The 1906 title is considered unofficial, however, as those Games are not recognized by the International Olympic Committee. Halmay and Daniels each held world records during their careers in the 100 freestyle and 200 freestyle.

Halmay won nine medals during his Olympic career to the eight medals earned by Daniels, although Daniels held the edge in gold medals with five to Halmay’s two. Both men are inductees of the International Swimming Hall of Fame.

RIE MASTENBROEK vs. RAGNHILD HVEGER

Most rivalries feature multiple major faceoffs over several years, but the rivalry between the Netherlands’ Rie Mastenbroek and Denmark’s Ragnhild Hveger consisted of one race. Yet, their one duel was an epic battle in the 400 freestyle at the 1936 Olympics in Berlin.

>> Zoltan Halmay & Charles Daniels

>> Rie Mastenbroek & Ragnhild Hveger

>> Andrew Charlton & Arne Borg

>> Dawn Fraser & Lorraine Crapp

The race was held on the last day of the Games, but by that point, Mastenbroek had enjoyed a fruitful competition. With gold medals already secured in the 100 freestyle and 400 freestyle relay plus a silver medal won in the 100 backstroke, Mastenbroek was a star and merely looking to finish the Olympiad with a flourish. Meanwhile, Hveger was hoping to play the role of spoiler. Little did she know, she’d also play the role of motivator.

Before the start of the 400 freestyle final, Hveger was given a box of chocolates, which she shared with her teammates and several competitors. Among those who did not receive a chocolate was Mastenbroek, who took the snub personally and used it as fuel for the final race of the Games. While Hveger held the lead for most of the race, Mastenbroek shifted into a higher gear down the stretch and reeled in her foe to prevail by more than a second and in Olympicrecord time.

While Mastenbroek became a swim instructor the next year, thereby losing her amateur status and Olympic eligibility, Hveger figured to have future opportunities for Olympic gold. But with World War II forcing the cancellation of the 1940 and 1944 Games, Hveger didn’t get that chance at her peak. She was also banned from the 1948 Games for her ties to Nazism, and while she raced at the 1952 Olympics, she was past her prime and finished fifth in the 400 freestyle. individual showdowns, Fraser and Crapp produced a split, Fraser winning the first of three consecutive Olympic titles in the 100 freestyle and Crapp winning convincingly in the 400 freestyle. Together, they helped Australia to gold and a world record in the 400 freestyle relay.

While Fraser and Crapp exchanged world records in the 100 freestyle and 200 freestyle early in their rivalry, Fraser took command in that area in 1956 and never yielded either standard back to her countrywoman, although Crapp maintained her world mark in the 400 freestyle. Meanwhile, Fraser beat Crapp in the 100 freestyle at the 1958 British Empire and Commonwealth Games.

The missing element in the rivalry was a 1956 showdown in the 200 freestyle. The event would have allowed for the women to meet at a point between their strengths, Fraser moving up from the 100 freestyle and Crapp moving down from the 400 freestyle. However, the 200 freestyle did not become part of the Olympic schedule until the 1968 Games.

ANDREW CHARLTON vs. ARNE BORG

At the 1924 and 1928 Olympic Games, Johnny Weissmuller was the undisputed star, thanks to back-to-back victories in the 100 freestyle and a gold medal in the 400 freestyle. In the shadow of Weissmuller, though, Australia’s Andrew “Boy” Charlton and Sweden’s Arne Borg built a strong rivalry.

In four individual races featuring Borg and Charlton between the 1924 and 1928 Games, each man walked away with four medals, including one gold medal. There was no doubt they defined the distance-freestyle events, their Olympic excellence supported by world-record performances, although the bulk were posted by Borg.

Charlton took the upper hand in the rivalry at the 1924 Olympics in Paris when he topped the field in the 1500 freestyle, leaving Borg with the silver medal. Borg added another silver medal in the 400 freestyle, with Charlton picking up the bronze medal. But Weissmuller was too much for either opponent to handle, as he won the race by more than a second despite being better known as a sprinter.

At the 1928 Olympics in Amsterdam, Borg reversed the finish of four years earlier by capturing gold in the 1500 freestyle, with Charlton grabbing the silver medal. Charlton (silver) and Borg (bronze) again medaled in the 400 freestyle, but as was the case at the previous Olympiad, they were beaten for the gold, this time by Argentina’s Alberto Zorrilla.

DAWN FRASER vs. LORRAINE CRAPP

The passing of the torch is a common way for rivalries to develop, largely due to the incumbent not wanting to yield power to the upstart. This scenario played out between Australians in the 1950s, as Dawn Fraser—her country’s rising star— supplanted Lorraine Crapp as the big name in a country that loved the sport.

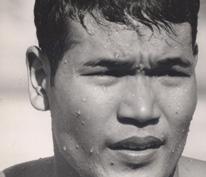

The 1956 Olympics allowed Fraser and Crapp to meet in their homeland, as Melbourne served as the host. In two MURRAY ROSE vs. TSUYOSHI YAMANAKA

The best rivalries are those that go back and forth, neither competitor with an overwhelming edge. On occasion, however, rivalries exist in which one athlete is dominant. Such was the case when Michael Phelps sat atop the sport and repeatedly owned his meetings with fellow American Ryan Lochte and Hungarian Laszlo Cseh.

A half-century earlier, Australian Murray Rose and Japan’s Tsuyoshi Yamanaka had a similarly one-sided rivalry. Between the 1956 Olympics in Melbourne and the 1960 Games in Rome, Rose and Yamanaka met in four distance-freestyle finals. In three of those events, Rose and Yamanaka posted sweeps of the gold and silver medals, with Rose standing on the top of the podium each time.

At a home Olympiad in 1956, Rose set a world record to beat Yamanaka in the 400 freestyle, then held on to defeat his future University of Southern California teammate in the 1500 freestyle. Four years later, the 400 free produced an identical result, this time Rose claiming a three-second win over Yamanaka. In the 1500 freestyle, Rose was dropped to the silver medal by Aussie John Konrads, while Yamanaka finished out of the medals in fourth.

At the 1961 Amateur Athletic Union Championships, Yamanaka finally reversed his fortunes, as he beat Rose in the 200 freestyle and 400 freestyle, the shorter distance producing a world record. For Yamanaka, the effort couldn’t erase his Olympic losses to Rose, but nonetheless was satisfying, given a statement he made months earlier.

“Before I die, I want to beat Murray Rose,” Yamanaka said.