21 minute read

WHO IS THIS GUY?

Before the summer of 2019, Texas A&M’s Shaine Casas wasn’t exactly impressing anyone with his swimming. But if his performances since then are any indication, the end results could be spectacular. His coaches see his potential as basically unlimited, and recent history makes it tough to disagree. As for Casas, he has similarly lofty expectations for himself.

BY DAVID RIEDER

Advertisement

In the spring of 2019, Shaine Casas was showing promising ability, but nothing that indicated that the then-19-year-old would win a national title in a few months. Certainly, no one— at least no one outside of his inner circle—imagined that Casas would soon become the country’s best collegiate swimmer.

The last time the United States held a major selection meet, the 2018 summer nationals, Casas was a total non-factor. He swam five events and qualified for two B-finals, one C-final and two D-finals. At his first NCAA Championships eight months later, Casas finished as high as 11th in the 200 fly in two consolation finals appearances.

Now, the 21-year-old McAllen, Texas, native and Texas A&M junior enters the college championship season with the top time in the country in four events while threatening American records. He has never competed internationally, but he has become a contender, if not a favorite, to qualify for the Tokyo Olympics. And the person least surprised by all that success?

Shaine Casas.

ALL HE NEEDED WAS A LEVEL PLAYING FIELD

“I definitely believed I was talented, and I was very ambitious,” Casas said. “I just felt like I didn’t have the same resources or opportunities as other swimmers. I felt like I had to wait to get my chance. I had to move for a summer just to get a chance to train with a really good club program doing doubles and a somewhat thought-out and methodical weight program with Nitro. I always felt like I was at a disadvantage until I got to the level that everybody was at, and I felt once the playing field was even, I could really explode and put distance on people.”

Since the summer of 2019, Casas has been on a hot streak, seemingly surpassing every expectation in sight, and he oozes confidence in his abilities. He’s flown somewhat under the radar since not a single national-level meet has been held since U.S. nationals in August 2019, but it was at that meet when Casas made his career breakthrough, posting massive time drops to win the 100 meter back and finish second in the 200 back (behind Austin Katz) and the 200 IM (behind Ryan Lochte).

In his sophomore season swimming for the Aggies (2019-20), Casas was masterful. He won SEC titles in the 200 yard back and 200 IM and finished second in the 100 back to reigning 50 meter back World champion Zane Waddell. He led off four A&M relays, including a victorious effort in the 200 medley, and the team finished in an impressive second place. He was set up to star at NCAAs, seeded first in the 200 back and 200 IM and second in the 400 IM.

But when the NCAA meet was canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic, Casas lost his big chance. Soon after, he lost another opportunity when the Olympic Trials and Olympics were postponed to 2021. Carrying so much momentum and knowing he had such a huge chance to prove himself on a significant stage, the cancellations were a severe bummer.

“I felt like I didn’t have any closure, really,” Casas said. “I was pretty frustrated, and I was upset for a while because I felt like I was robbed. Going into a meet seeded first, there was a good possibility I could have won. I could have lost, also, but I felt like I had a lot to prove that season.”

SOMETHING SPECIAL

When Texas A&M men’s head coach Jay Holmes and associate head coach Jason Calanog were interviewed together, they recalled their first impression of Casas upon his arrival in College Station in the summer of 2018...and both men laughed.

“He broke his ankle at U.S. junior camp, so he was on crutches for six to eight weeks when he got here, so he wasn’t

doing anything. He was just a lazy bum just hanging out at practice, just pulling,” Calanog said. “He really went to nationals (that year)—I swear to God...what was it, Jay, after like three or four weeks of training?...and he went all best times and was (the top 18-and-under finisher at nationals).

“Really, that’s when we knew that we had something special.”

The coaches described the swimmer they now see every day in practice as a relatively normal college swimmer who “just happens to be super-talented at swimming”...and a good teammate who rarely takes things too seriously, but he can be stubborn and complain about a set he doesn’t like.

“His brain is really like a 10-yearold, but he’s in a 21-year-old body,” said Calanog, who actually believes that Casas has the same natural talent and abilities of a high school swimmer he once coached in Jacksonville: a certain Caeleb Dressel.

“He just doesn’t know his potential yet because it’s literally limitless. With strokes, distances, he has no idea. And we have no idea. We’re just trying to prepare him the best we can,” Calanog said. “I never thought I would have another chance to coach somebody this good,” he added.

Exactly what boundaries can he push? >> In the 100 meter back, his 52.72 from 2019 nationals made him the seventh-fastest American of all-time in

He’s already within striking distance the event, and he finished the year ranked fifth globally and second among Americans behind Ryan Murphy. His of American records in backstroke and 200 back time of 1:55.79 was good for sixth in the world in 2019, third among Americans behind Ryan Murphy and Austin Katz. (Pictured: Casas after winning 100 back at 2019 U.S. nationals) [PHOTO BY CONNOR TRIMBLE ] butterfly short course, and his coaches insist he’s even better long course. His weak stroke? Not breaststroke. “He talks a PROGRESSION OF TIMES lot of trash to our breaststrokers,” Holmes SCY PREVIOUS BEST 2019-20 2020-21 ALL-TIME RANK said. “He has gotten up and raced them a 100 Back 45.94 44.48 43.87 4th couple times in practice and given them all they can handle.” 200 Back 1:39.84 1:37.20 1:36.55 4th

But remember, Casas is just 21, a 100 Fly 45.91 45.26 44.98 Just outside top 25 college junior with untapped capability, 200 Fly 1:41.31 1:40.33 1:39.23 8th but a long process of growth ahead of him 100 IM — — 47.23 1st (unofficial) as he seeks to join the swimming world’s elite ranks. 200 IM 1:42.29 1:39.91 1:38.95 3rd Even as they marvel at his capabilities, Holmes and Calanog want to make sure coming back to training for a second time to be even more difficult, they help set him up for sustained improvement and consistency. and briefly, he even questioned whether he could return to his usual That means teaching him skills in mental preparation, and Calanog form. But as the college season began, those questions quickly has been applying what he learned from his days at Bolles working went by the wayside as he put together brilliant performances meet with Dressel, Ryan Murphy and Joseph Schooling. Sometimes, after meet. they have to preach patience. “I think my physical maturity has finally matched my talent,”

“We encourage Shaine to grow, but we’re not trying to have Casas said. “I felt like whenever I got here, my strokes were fine, him grow up too fast because he needs to be able to go through but I was too weak, too slow off the walls, not enough power in this process himself and be able to figure all this stuff out,” Holmes and out of turns. I really focused in the weight room, lost fat. I’ve said. “We’re not trying to run too fast here. We want Shaine to be had a dramatic physical change.” Shaine and grow up and experience this. I really believe the older The highlights from Casas’ brilliant fall include a stunning 200 he gets, the more dangerous he’s going to get. It’s going to be fun yard fly at a dual meet against TCU. Casas had come to college for us.” as a butterflyer, and his only junior nationals title had come in the 100 meter fly as a 17-year-old in 2017 when he tied for first REBOUNDING FROM COVID-19 with Alexei Sancov in 53.24. He swam mostly butterfly through

Shortly after returning to swimming in late spring last year, his freshman year before his backstroke exploded and suddenly Casas had to take another break from the pool when he contracted become his best stroke. Still, he was training fly, so he expected COVID-19. While he did not suffer from severe symptoms, he found that stroke might catch up to his backstroke eventually.

will be chasing tough American records in all his events, but his recent progression shows that breaking national marks is inevitable.

“Honestly, it doesn’t matter what I swim,” Casas said. “I’m just focusing on being a racer and being in the moment and doing what I can to win, because that’s honestly the only thing that matters these next couple meets. Times are cool, but it’s all about winning. First place is the one that’s remembered.”

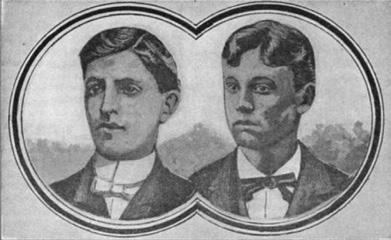

KILLER INSTINCT After the college season, Casas intends to chase the Olympics. In the 100 meter back, his 52.72 from 2019 nationals made him the seventh-fastest American of alltime in the event, and he finished the year ranked fifth globally and second among Americans behind Ryan Murphy. His 200 back time of 1:55.79 was good for sixth in the world in 2019, third among Americans behind Murphy and Katz. And he bears watching in the butterfly events, as well. But on top of that, Casas has started to build that edge, the killer instinct you see in all the great champions—that little bit extra that could push him over the top. >>(From left) Texas A&M associate head coach Jason Calanog and head coach Jay Holmes recalled their first Take his mentality regarding training impression of Shaine Casas when he arrived on campus as a freshman. Casas had broken his ankle at U.S. junior camp, yet he still went to nationals that year after just three or four weeks of training. “And he went all best times and racing: “Honestly, it starts months and was (the top 18-and-under finisher at nationals),” said Calanog. “That’s when we knew that we had something before,” he said. “As the season starts, special.” [PHOTO BY CRAIG BISACRE/ TEXAS A&M ATHLETICS] you’re thinking about, ‘Oh, what’s this guy doing? How hard is this guy pushing

“I went about a second-and-a-half faster than I thought I was himself?’ It’s just the little details and how going. I thought I was going about 1:40 or 1:41-low, and I looked, you can beat them at every single thing so that when it comes and I was 1:39-low, and I was like, ‘OK, that’s pretty cool.’ I didn’t down to it, you just don’t lose. really know my butterfly yet, but I’ve kept at it, and it’s finally “There’s a physical part—just outwork your competition—and gotten to the level of my backstroke,” Casas said. “That was just then the mental part, which is even more important...which is just a random stellar swim that I had. I honestly couldn’t explain that knowing and being 100% confident that you can beat them, no one to you. It just happened.” And then, at A&M’s Art Adamson Invitational, Casas swam matter what. Even if they want it, you just want it more.” the 200 yard IM in the same pool where Dressel had annihilated the American record (1:38.13) almost three years earlier, and * * * Casas blasted a 1:38.95 200 IM, good for the third-fastest performance ever. Still, Casas is a normal college kid who loves playing video

“When Caeleb went that, I was like, ‘That pool record might games whenever he gets the chance—“I have a big range of stay for 20, 30, 40 years,’” Calanog said. “When (Casas) goes 1:38 games,” he said—and he loves his three brothers, Sean, Seth and two years after, I was like, ‘Oh my God, Jay! Maybe that thing’s Jimmy, and his mother, Monica. It’s just that every chance he’s actually going to be broken!’” had to race in the pool over the past two years, he has simply

In early January, Casas competed in long course for the first been astonishing. time since 2019 nationals when he swam at the TYR Pro Swim Of course, COVID has limited those chances, and Casas never Series in San Antonio. There, he won the 100 fly in 51.91 and also got to show just how good he could be in 2020. But when those finished second in both the 100 (54.32) and 200 back (1:58.04), on both occasions behind Olympic champion Murphy, who Casas was racing head-to-head for the very first time. So in his event lineup, Casas has options. That includes on the championship meets do return, Casas will get his chance to close out a season on his own terms. “I feel like a legacy I would love to have is to be just the guy NCAA level, where he would be a massive national title favorite that could do anything, basically,” Casas said. “I’m no Michael in both backstroke events and the 200 IM, but also a massive threat Phelps. There can only be one. I just want to be known as the kid in both butterfly events, where he could face off deep fields that that just always seemed to flip the switch and keep going, even include Georgia’s Luca Urlando and Camden Murphy, Texas’ when people thought it was done, or keep surprising them, even Alvin Jiang and Sam Pomajevich and Cal’s Trenton Julian. Casas when they thought they had seen everything.”

THE VALUE OF SWIMMING IN

BY BRUCE WIGO

In the early 1900s, there was scarcely an American alive who was unfamiliar with the name of Frederick Funston. He was the most decorated and celebrated hero of the Philippine-American War (1899-1902)—famous in military and swimming history for his willingness to have his men swim across rivers, under fire, when, according to press reports, “They couldn’t otherwise get at the enemy quickly enough to suit them.”

Funston was a man who, upon his untimely death in 1917, had forts, camps, streets, avenues, schools, statues and even a class of naval transport ships named after him. In Iola, Kan., his boyhood home has been preserved and still operates as a biographical museum.

But today, he is the target of a “cancel culture” that seeks to remove his name from public spaces, along with the names of Columbus, Paul Revere, Washington and Lincoln.

By his own admission, Funston committed what would be considered to be war crimes against the Filipino insurgents, and while the imperialist subjugation of the Philippines was an atrocious affront to U.S. ideals, there are things that can be learned from Funston’s story and the role he played in American history and swimming.

ALWAYS KNOWN AS A “FIGHTER”

Funston was a “little” man—only 5 feet 4 inches tall and 100 pounds—but so was Napoleon a small man. In spite of his size—or because of it—he was always known as a “fighter.”

His early adult life was one of almost unbelievable adventure. In the early 1890s, he participated in scientific expeditions in the Dakota Badlands, Death Valley and in Alaska along the Klondike and Yukon Rivers. Then in 1896, he sneaked into Cuba to join insurgents in their revolution against Spain—and he found his calling.

He fought in 22 battles against the Spanish, was wounded three times, and had several horses shot out from under him. When America declared war on Spain, he returned to Kansas, where he was appointed a colonel and commandant of the 20th Kansas Volunteers. The war ended before his unit could join the fight, but he finally got to see action in the Philippines, fighting the Filipinos who opposed America’s imperialistic ambitions and sought their own independence.

The Kansas 20th had their first encounter with the enemy in

>> Brig. Gen. Frederick Funston was on the cover of Harper’s Weekly on Nov. 11, 1899. He served 19 years in the military from 1898-1917 and was promoted to major general in November 1914.

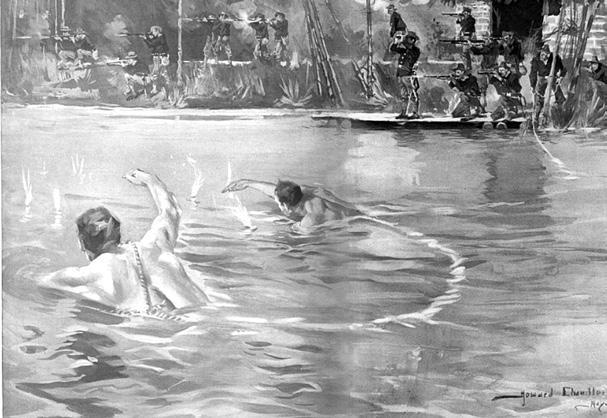

March of 1899 when they reached the banks of a stream and came under fire from the rebels entrenched on the opposite bank. Funston selected 20 men who could swim and instructed the rest of the company to keep the heads of the enemy below their trenches, using their Mauser rifles and Colt-Browning machine guns.

With a shout of “Let’s go, men,” and holding his revolver up out of the water, he led the swimmers across the river. On reaching the other side, the protective fire stopped, and the little band of Kansans charged and captured 80 Filipino insurgents. A “hero” was in the making.

In the weeks that followed, Funston and his men proved the utility of swimming in combat situations several more times. On April 25, their advance was halted by another river. Outmanned and outgunned, the Filipinos had retreated across a railroad bridge, which they destroyed after the last man had passed. Now they were entrenched on the opposite shore.

Thinking it important to get after them at once, Funston and several volunteers crawled along the wreck of the bridge, dodging a few happily misdirected bullets. When the bridge could take them no farther, Funston dropped into the water and swam to the beach, followed by the others. Emerging from the water with a yell and a few shots, they captured what was left of the rebels. The opposite bank secure, engineers were able to construct a foot bridge over the broken span of the Bag-Bag Bridge, and the rest of Funston’s infantry continued their advance.

the Rio Grande, where they found the locals again entrenched in force on the opposite shore, protecting the remnants of another bridge. Some 600 yards below the bridge, scouts found a small raft that the enemy had unsuccessfully attempted to burn. To turn this raft into a small ferry would require swimmers to carry a heavy rope to the other side, necessarily within close proximity to enemy trenches. When he asked for volunteers who could swim, Pvt. Edward White and Pvt. William Trembley were selected. “White and Trembley stripped stark naked behind the cover of a clump of bamboos,” Funston wrote in his report. “They took the ends of the rope between them and plunged into the river. As soon as they did, the ‘music’ began. They were powerful swimmers, but their progress was >> American soldiers in the Philippines swimming to an assault on the insurgent entrenchments. slow, owing to the strength required to drag [DRAWN BY FREDERIC REMINGTON] the heavy rope, which was being paid out to them by their comrades on the bank.” The “music” Funston referred to was the sound of a hundred men firing automatic rifles, the Hotchkiss revolving cannon and Colt machine guns. “The greatest lover of the sensational could not have wished for anything more thrilling,” Funston wrote. “The two men battling slowly across the current with the snakelike rope dragging after them; the grim and silent men firing with top speed over their heads into the trenches on the other bank; the continuous popping of the revolving cannon, a gun of the pompom type, the steady drumming of Gatling guns and the constant succession of crashes from the big field pieces; the thin film of smoke rising along both banks of the river, and the air filled with dust thrown up by striking shells and bullets, made the scene that could not fade from one’s memory in many a lifetime. There was now being carried out one of the most difficult of military operations, for the Rio Grande was, in fact, a vast moat for the defense on the north bank. “Finally, the two swimmers, panting and all but exhausted, dragged themselves out on the other bank at the base of the world that had been so mercilessly battered. The fire of the artillery and the machine guns now ceased for fear of hitting the two men, and only a few of the detail of infantrymen were allowed to fire, under strict supervision, as their bullets must clear White and Trembley by only a few feet if the latter stood up. There was, however, no cessation of the fire on the works between them and the north end of the bridge. “The situation of the two naked and unarmed men was, of course, precarious, as they were separated from all the rest of the division, while all around them were hundreds of the enemy, who were, however, prevented from molesting them by the fire still sweeping adjacent trenches. Finally, White and Trembley made a noose in the end of the rope, gathered in several feet of slack, and, astonishing to relate, made a dash for the trench and slipped it over one of the bamboo uprights of the work, returning then to the river bank, while we opened fire again directly over them to prevent the occupants of the trench from cutting the rope.” The ferry line now established, it was found that the raft would >> Outmanned and outgunned, the Filipinos had retreated across a railroad bridge, support only eight men at a time. So Funston and seven others which they destroyed after the last man had passed. Now they were entrenched on the opposite shore. Thinking it important to get after them at once, Funston and several volunteers crawled along the wreck of the bridge, dodging a few happily pulled themselves across by the rope, and in a few moments, had joined White and Trembley on the other bank. Two men took the raft misdirected bullets. back for another load, and as soon as two dozen had landed, they

NATIONAL HEROES

The “yellow press” turned Funston, White and Trembley into national heroes. They were awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor, and Thomas Edison’s film company reenacted their feats with actors in New Jersey. The fame of Fred Funston and the 20th Kansas Volunteers was further magnified in popular culture through musical compositions for both piano and community bands. Among the titles were “Funston and His Men,” “Funston’s ‘Fighting 20th’” and “The Dare Devil March.” Editorials declared that their feats >> To turn a raft into a small ferry (top were “likely to make swimming so illustration) required two swimmers popular that everybody and everything to drag a heavy rope to the other side of the Rio Grande within close will adopt it,” and that “ambitious proximity to enemy trenches. Privates youths will hereafter begin preparations William Trembley and Edward White for their careers by learning to swim.” (inset illustration, from left) did so amidst the firing of automatic rifles, This led to a boom in pool building in a Hotchkiss revolving cannon and Colt communities and schools across the machine guns! Successful in their nation as well as swimming instruction mission, the two men, along with Funston, became national heroes and were awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor. for our nation’s military.

For his work, President McKinley rewarded him a promotion to brigadier general when he was only 36 years old. In 1906, Gen. Funston was in command of the military base at the Presidio in San Francisco when the earthquake struck. His leadership and actions were widely praised and credited with saving the city from chaos, starvation, looting and destruction.

In 1914, when the Mexican Revolution broke out, President Wilson assigned Funston to oversee the occupation of Veracruz. He was later put in charge of the 150,000 men assigned to protect the 2,000-mile U.S.-Mexican border. Among his subordinates were Douglas MacArthur and John “Blackjack” Pershing.

Shortly before the United States entered World War I on April 6, 1917, Funston, now a major general since November 1914, was destined to lead the American Expeditionary Forces to Europe, but he died of a heart attack a month-anda-half earlier at the age of 51, leaving the position to General Pershing. >> The fame of Funston and the 20th Kansas Volunteers was further magnified in popular culture through musical compositions for both piano and community bands. Among the titles were “Funston and His Men,” “Funston’s ‘Fighting 20th’” and “The Dare Devil March” (pictured).

Bruce Wigo, historian and consultant at the International Swimming Hall of Fame, served as president/CEO of ISHOF from 2005-17. The illustrations provided with this story are from his private collection.

In this month’s March issue, Bruce Wigo explores the value of swimming to military history. For a related story, see page 9 (“DID YOU KNOW: about Prince Dabulamanzi and the Battle of Isandlwana?”)