Transformation, Intensification

Moderator:

Speakers:

YW = Yvonne Weldon, SG = Stephen Garton, RD = Robyn Dowling, CL = Catherine Lassen (moderator), AL = Anne Lacaton (speaker), JPV = Jean-Philippe Vassal (speaker), HF = Hannes Frykholm, KG = Kate Goodwin, GJ = Graham Jahn, BS = Bridget Smyth

Catherine Lassen

Anne Lacaton, Jean-Philippe Vassal

5 Abstract

6 Welcome to Country Yvonne Weldon, Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council

6 Opening Prof Stephen Garton, Vice Chancellor, University of Sydney

6 Opening Prof Robyn Dowling, Head of School and Dean, Sydney School of Architecture, Design and Planning

8 Introduction

Catherine Lassen, Senior Lecturer and Rothwell Chair Coordinator, Sydney School of Architecture, Design and Planning

9 Living in the City: Transformation, Intensification

Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal

32 Discussion

38 Bios and Further Readings

Abstract

Session 1 focused on the design philosophy and principles in the work of Lacaton & Vassal, as a way of introducing the overarching theme of the Symposium, “Living in the City,” and the question of housing. In addition to contextualising housing as essential to the quality of everyday life for inhabitants and within cities, the presentations by Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal illustrated how the development of fundamental design principles shaped, and was in turn shaped by, their practice’s design and research projects.

Drawing on architectural ideals associated with works such as Le Corbusier’s Maison Dom-Ino (1914–15) and the Case Study Houses program (1945–66) in the United States, Lacaton & Vassal advocate that we “build simple,” using a minimum of materials and construction elements. At the same time, their aim is to “build double” by adding about 50% of unprogrammed space for freedom of use and movement and to look for “a flat like a villa” to provide a generosity of inhabitable indoor and outdoor spaces. Most crucial in their work, however, is the particular attention to and appreciation for the existing, advocating for a careful and precise examination of existing situations, which they refer to as “situationes urbaines capables,” or urban situations with capacities. This represents a rejection of the dominant tendency for demolition and new construction, advocating instead for meaningful architectural and urban transformations that are carried out with care, precision and ambition, as demonstrated in the Grand Parc project in Bordeaux by Lacaton & Vassal in collaboration with Frédéric Druot and Christophe Hutin.

In the discussion, Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal elaborated on their attitude towards the modern project. In their view, while the modern movement powerfully contributed to the liberation of architectural design through simple structural systems and materials, they are highly critical of the ‘tabula rasa’ approach promoted in modernist urban planning projects. They consider such doctrines, which ignore almost any given context—social, historical or otherwise—as deeply problematic and “an act of violence.” At the same time, they emphasised that the principles of modern architecture have been very influential to the development of their own design philosophy. The discussion also turned to the situation in Australia, where many housing complexes have multiple private owners rather than a single (social) housing association, as is common in France. While recognising the challenges posed by multiple individual owners for large transformation projects, they were hopeful that, through a commitment to the design principles of care, precision and ambition in relation to the potential in what already exists, such challenges can be overcome. In other words—and this became clear in their presentation—immense care towards the existing is not limited to architectural and physical objects, but also includes the social and historical structures embedded within them.

SYDNEY SCHOOL 5

The Symposium began with Yvonne Weldon’s powerful Welcome to Country. We acknowledge the Welcome to Country as a living, cultural practice and would like to invite the reader to take the time to listen to it in the recording.

SG

Thank you. I’m Stephen Garton, the Vice Chancellor. A pleasure to welcome you all here to the Rothwell Chair Symposium. But before I begin, let me also acknowledge that we are here today on the land of the Gadigal people of the Eora Nation, and pay my respects to Elders past, present, and future and thank Yvonne for her generous Welcome and Acknowledgement of Country. It’s always humbling for the University to think that research and education has been going on here for tens of thousands of years. And of course, in the context of this Symposium, we now know that First Nations peoples in Australia transformed the environment, actively engaged with the environment but in a sympathetic way that was nurturing and caring for the Country in the long term. That’s one of the reasons why the University’s new sustainability strategy has Caring for Country as one of its key planks, because we want to learn from the First Nations’ approach to managing the environment, which is so important for us all.

It’s a great pleasure to welcome you all here for this event and particularly our special guests Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal, who are going to give the Symposium presentation. Their presence here as the Rothwell Chairs owes a great deal to Susan and Garry Rothwell whose generous donation has made all of this possible. So, I really want to thank you on behalf of the University and the broader community for your generosity to enable this great event to happen.

Wonderful things can happen from philanthropy, and this is just one of the ways in which we can embrace and show in this particular context the importance of architecture, the importance of the environment and the ways in which we, every human, lives in a space and engages with space. And therefore, how we manage space, how we construct space is so important to everyday life, consciousness, and our sense of wellbeing.

So, it’s a great opportunity, I think, to hear from very distinguished architects about how they approach that classic problem and classic questions for us all. In that context, I have to say that I have a great deal of fondness for the School of Architecture, Design and Planning. They are a bunch of wonderful people and colleagues who have impressed me with their innovation, their engagement with student learning, their research. But my estimation of the sta and the students has risen considerably in the context of this event. How did you pick the Pritzker Prize winners a year before they got it? I mean, that is just fantastic. What insight, what understanding of the discipline! Congratulations, that is really good. I think the applications for future versions of the Chair will be bountiful because everyone will want a Pritzker and, therefore, they will want a Rothwell before they get a Pritzker.

It is a great opportunity to welcome these very distinguished architects. I watched a YouTube video this morning just to get a bit of their sense of the democratisation of landscape. One thing that really impressed me was the idea of not just demolishing buildings to build anew but to reconstruct and reconfigure architecture in more meaningful ways that really open up the space for human living. It’s a terrific and—from a historian’s perspective—a great way of approaching architecture.

So, it’s now my pleasure to introduce the Dean, Professor Robyn Dowling, who will say a few more words and a more informed set of words than I will. Thank you, Robyn.

RD

Thanks very much, Stephen, for your very kind words. I would also like to acknowledge that we are meeting on the Land of the Gadigal People of the Eora Nation, and to pay my respect to Elders, past, present and emerging. Vice-Chancellor, Garry and Susan, Anne and Jean-Philippe, guests who are here, and I don’t know what number we are up to now, but our guests online, thank you for coming tonight.

Transformation, Intensification 6

Yvonne Weldon

Welcome to Country

Stephen Garton

Opening Robyn Dowling Opening

The Symposium really marks the launch of the Garry and Susan Rothwell Chair in Architectural Design Leadership made possible, as Stephen mentioned, by the generous gift from Susan and Garry. Now, I’m intrigued that Stephen says he loves the architecture group, because architecture and design schools take pride in breaking rules and flouting convention. Which is very odd for those who know me that I lead such a school. And in the spirit of that, the Rothwell Chair is actually not your usual university-endowed professorship. First of all, we have two, not one, Rothwell Co-Chairs in recognition of the importance of collaboration and partnership in design processes, and in high quality design outcomes. Our Co-Chairs come from the architectural profession, rather than the academy, which is actually really important to us in the School. And the Rothwell Chair is a program of activities, it’s not a single event and it’s not just one person. We have a postdoctoral researcher, Hannes Frykholm, who will support Anne Lacaton and JeanPhilippe Vassal with the research elements of the program. Hannes will begin employment with the University of Sydney later in the year, we hope, when he can travel to Australia, but he joins us from Sweden later in the panel this evening. The Rothwell Chair also supports a PhD top-up scholarship awarded to Nathan Etherington, who’s also here this evening, an architect completing a PhD in the School.

While the approach of the Chair might be a little unconventional, the practices of the Chair and its activities allow the School to continue the mission it’s been pursuing since its inception a little over one hundred years ago to lead and inspire thought on built and designed environments. First, in our School, our sta and students work in partnership with the professions and each other. Such collaboration has been woven into the fabric of the Rothwell Program. Sta , students, practitioners, friends from architecture, urban policy and design are all in the audience tonight. And the activities we have planned as part of the Chair Program will include design studios for our students, classes for emerging and mid-career architects. The program is a fantastic opportunity for us in the School, in collaboration with our Co-Chairs, to apply creativity, rigour, and a collaborative mindset to advance knowledge and build better places. And second, I think it’s important that the University, and the School, do not turn away from societal challenges. The School proudly nurtures our people to be experimental, imaginative and, importantly, to be critical. Our students’ design skills have been equally informed by classes from artists like Lloyd Rees, and by participating in radical experiments with building self-su cient housing at the back of the Wilkinson Building.

Our Rothwell Co-Chairs have asked us to bring that tradition to life for the 21st century. They have drawn our attention to a wicked problem—how to build great cities with kindness, generosity, and e ciency in mind. I have no doubt that the conversations throughout this Symposium will be lively, but the conversations will also be di cult, as solutions to a ordable housing that may make us feel uncomfortable emerge. The Symposium, I hope, will rea rm the tradition of the university of debate and questioning.

To conclude, I’m also delighted to welcome you here to the Symposium and the launch event and to once again thank Garry and Susan very sincerely. I will leave it to my colleague, Catherine Lassen, to provide you with an introduction to Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal as our Rothwell Co-Chairs.

I think it was one of my first jobs when I started as Dean two-and-a-bit years ago, when we asked the architecture discipline to suggest Rothwell Chairs, we kept coming back to Lacaton & Vassal because of their work, that was at the intersection of architecture and urban planning, their thoughtfulness, and their broad social ambitions. We look forward to welcoming them to Sydney in person at some point but for now are equally excited for the Symposium to come over the next three days.

Thank you.

SYDNEY SCHOOL 7

Catherine Lassen Introduction

CL

Thanks Robyn, and hello everyone. My name is Catherine Lassen, I’m an architect and academic in the architecture discipline here at the University of Sydney. As the Rothwell Coordinator, it’s both a privilege, and my pleasure, to welcome Anne Lacaton and JeanPhilippe Vassal as our inaugural Rothwell Co-Chairs of architecture and urbanism and our guest lecturers here tonight and today in Europe. I also have a short housekeeping task, I have to tell you that this session is going to be recorded, I hope that’s okay with everyone. And in case of emergency, museum sta will show us to the exit.

With the award of this year’s Pritzker Prize, Lacaton & Vassal now need no introduction, but I thought it might be good to say a few words about why they were our first choice as Co-Chairs for this wonderful program, that, thanks to Garry and Susan Rothwell, encompasses public events, such as the discussions this evening and over the coming days. Together with, as Robyn mentioned, an annual architecture studio and developing scholarly research around the architects’ nominated topic, that is, dealing with contemporary urban conditions to explore optimal ways of living in the city. Lacaton & Vassal—and we are very grateful to them for this—have curated this Symposium with us and will be joining us on each of the three evenings this week to virtually launch their Rothwell Program and to introduce their agenda that will be developed over the three-year period.

They are remarkably well qualified to lead a program that, as Robyn mentions, ambitiously connects significant architectural and urban design and the academy with practice. Having established their studio in Paris in 1987, over the years they have won many prestigious international awards for their thoughtful and precise architecture, urban thinking, social commitment, and investment in sustainability. Some of these that precede the Pritzker include the EU Mies Van Der Rohe Award in 2019, the Global Award for Sustainable Architecture in 2018, the Grand Prix National d’Architecture in France, the international RIBA fellowship in 2009 and so forth.

Both architects have long-standing commitments to academia, they are highly respected educators, continuing to teach throughout their developing professional careers across Europe and in the United States, in some of the world’s best schools of architecture. Anne Lacaton has taught at the GSD at Harvard 2010–2011, at the EPFL in Lausanne, she has a very long relationship teaching at ETSAM in Madrid and, more recently, was also Associate Professor of Architecture and Design at the ETH in Zürich from 2017–2020. Jean-Philippe Vassal has taught at Düsseldorf, also at Lausanne, he taught at the TU Berlin from 2007–2010 and is currently Associate Professor at the UDK Berlin where he has taught since 2012. So, our students are very lucky.

But what I would most like to emphasise is the way that Lacaton & Vassal have crafted a very precise and personal architectural position, one that poses an interesting intersection between a pragmatic acceptance of many current challenges for the profession—for example, engaging with the economic and procurement details of major building construction systems—whilst renewing selected ideals of early and mid-century modernism. This extremely thoughtful approach to carefully and strategically continue elements that we might associate with the project of modernity whilst incorporating intelligent critique to locate each new project in a contemporary setting, searching for real innovation, often understated, and to do this in a media-saturated world that privileges the rapid consumption of architectural imagery is refreshing and, I think, very hopeful, as well as remarkable.

Di erent aspects of their approach in this position are touched on and connected through local and international discussions over the coming days. A precise intersection of architecture and urban design connected to the experience of the interior, I see as one continuous, ambitious thread. Another is alluded to in their Rothwell topic. Central to early twentieth century architectural experiments was a key question: How do we want to live? And they revive that question for the current environment. Innovation is looked for in Lacaton & Vassal’s work through a deep understanding of all existing contexts to a

Transformation, Intensification 8

project, including its history. In our Symposium discussions about social and a ordable housing tomorrow evening, Irénée Scalbert will present a close reading of an important social housing project in France from the 1970s and in the final session on Thursday, Anne and Jean-Philippe will meet with architects who also act pragmatically as developers, including Andreas Hofer, who is the current director of the IBA 2027—the one hundred year reimagining of the famous early-twentieth-century Stuttgart Weissenhofsiedlung

This intersection of history and pragmatic engagement is very powerful in their work, I think. Disciplinary literacy is here connected with detailed understanding of building realisation processes. And, in Lacaton & Vassal’s work, it helps make contemporary architectural and urban sense of larger political and social ideals. These elements and more o er sophisticated and, sometimes, subtle connections with history, context, the idea of the city, modernism, popularity, industrial building systems and details, economy of means coupled with the desire for living better in urban environments. Collectively, this approach o ers us and our students an inspiring example for framing one’s own architectural position today. We are delighted that tonight’s presentation is just an introduction, so over the coming days—and, indeed, three years—some of these questions will be further explored, we will start some conversations. By examining all these layers of thought, we can begin to read this work, and the lessons it o ers us tonight, here and across the globe. Please join me in welcoming Anne and Jean-Philippe.

AL

Jean-Philippe Vassal and I are delighted to accept the invitation of the University of Sydney for the three-year Rothwell Chair.1 We especially thank Susan and Garry Rothwell and the University of Sydney for this invitation. And today, it is a great pleasure for us to finally launch the Chair—remotely, unfortunately—with this three-day Symposium. Together with the University, we agreed to focus on the topic of living in big cities, which leads, first of all, to the subject of housing. Inhabiting is the most wonderful challenge of contemporary society, yet also certainly the most critical. Our aim in the Chair, as in our practice, is to define in all aspects the conditions for the provision of good and a ordable housing in the big city, which for us is the essential condition for making the city much better for all inhabitants. It starts by defining, in an ambitious way, what good housing is, and what inhabitants expect—and have the right to expect—of their housing in terms of quality and pleasure in everyday life. We will come back to this in our presentation.

Housing is a basic and essential element that makes up a city and which contributes to the quality of the city. This is the reason why it is important, in our opinion, to start thinking about cities in relation to the quality of housing and to emphasise both pleasure and a ordability. In this way, we reverse conventional methods of city planning, prioritising a strategy of situations, rather than a master plan vision. Part of the solution comes from the city itself and from the potential that already exists, which must be exploited and not ignored or wasted. We need to pay careful attention to the existing from the inside to understand the values and the potential. The transformation of the existing, with ambition and care, instead of demolition and rebuilding, better use of the land, a precise and sensitive densification—case by case, place by place—also provides solutions for creating good housing and improving the quality of housing. It is much more beneficial in terms of ecology, of economy, of mixing people and, overall, for quality of life.

We will now try to develop our ideas about all this through the presentation of our design philosophy and some projects that we have realised in our o ce.

JPV

Because we don’t know the situation in Australia, in Sydney, very well, I think it’s interesting to try to establish a bridge, between Europe and Australia, between Paris and Sydney, to share these questions, to learn from what is happening in each situation. I think it will be

SYDNEY SCHOOL 9

1 Anne Lacaton & Jean-Philippe Vassal, Sydney School of Architecture, Design and Planning, Rothwell Chair Symposium, April 27, 2021, Session 1, “Living in the City: Transformation, Intensification,” video recording, 22:15. Refer to last page for link to recording.

Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal Transformation, Intensification

2 Frei Otto’s participatory Ökohaus project was part of the International Building Exhibition (IBA) in Berlin in 1987. See also Christophe Hutin’s contribution to the Rothwell Chair Symposium 2021, session 3, “Living in the City: Re-thinking Housing Models.”

3 Polykatoikia is a term used for multi-level apartment buildings in Athens, Greece, a building typology that developed between 1929 and 1940 as a response to substantial growth in population.

very interesting to make this very long trip from here to Australia, from Paris to Sydney, to share these questions about living in the city and the important challenge of housing.

We think it’s important to come back to simple gestures or, as we say: build simply. It’s an eternal gesture. It reminds me of when, just after I finished my diploma, I was in Africa with some friends on a sand dune, not far from the big city of Niamey on the other side of the river Niger. It started just by fixing some branches in the sand, making a circle, then bending these branches in order to make this form, this kind of roof. It’s a pleasant moment. It’s a moment to discuss, to share experiences, to laugh, to be happy.

Then you surround the branches with panels of straw that allow the air to pass through, you move around the straw hut and then you place another kind of straw, which is much thinner, on the roof that will provide protection from the rain in the rainy season. And then you create this straw hut that will provide shade when it is too hot outside. The straw hut has a fence around it and, just in front, nine branches are fixed in the sand to support a large roof, a sort of living room on top of the sand dune from which you can look at the landscape. It is so simple. It took just these three days working with my friends in this situation (fig. 1).

We also find this simplicity in the 1950s, in some houses that were built with a bare minimum of components, with a minimum of steel, with a minimum of concrete and with glass windows all around, and in relation to the landscape. This produced some of the most beautiful villas on the West Coast [of the United States]. It was a social housing program, the Case Study House program (1945–1966), which resulted in very, very economical houses that nonetheless provided situations of luxury, simply and with minimum elements. For us, these houses in Australia by Glenn Murcutt are also very beautiful and elegant villas like those we find in the countryside, or in the landscape, or in the forest. Simplicity, build simply, go back to very, very simple things. This seems for us to be absolutely essential.

It means floors are like grounds. In this way, we return to the Maison Dom-Ino of Le Corbusier—just a system of columns, beams, floors, and stairs from one level to another and to the roof. Very, very simple. Or, like this project by Frei Otto in Berlin Tiergarten, Ökohaus, or ecological houses, which proposed platforms, each 7 metres from the next, on which the inhabitants had the opportunity to develop their own housing. I think Christophe Hutin will also talk about this project tomorrow.2

But we can also find this simplicity on a larger scale in the city of Athens, in a system called Polykatoikia, a system of Maison Dom-Ino at the scale of the city: minimum materials to create grounds to propose floors.3 This is also about playing with the climate, and not fighting against it. We have seen in Europe over the last 20 years that the climate was viewed as an enemy, and we don’t want to imagine it in that way. This means that the climate is seen as a friend, and we have to play with it, to use its qualities and characteristics. So, it is about working with solar energy in a passive way, taking the energy and the heat from the south when you need it, but also working with natural ventilation, with screens, with filters. We can really learn a lot from greenhouse technology and its extreme simplicity, extreme robustness and, at the same time, total orientation towards the climate, and adapt this to housing situations (fig. 2).

This simplicity, the fact of working with the climate in a simple way, means that we want to deal with simple elements— the light, the air, doing with the minimum. In this way, a ordability should not be that far away.

Build double. This means to build more, to give more freedom linked to this idea of inhabiting—in all situations: outside the city, but also inside the city. Inhabiting beyond the functional conveys pleasure, generosity, freedom to occupy a space (fig. 3). A space for living must be generous, comfortable, adaptable, flexible, luxurious, a ordable. Dwellings must o er freedom of use, to generate possibilities for evolution, interpretation and appropriation. In general, standards of housing are too low, too restricting. For us, the principle of a standard minimum for the living space is wrong. O er as much extra space

Transformation, Intensification 10

“Inhabiting is the most wonderful challenge of contemporary society, yet also certainly the most critical.”

Anne Lacaton

SYDNEY SCHOOL 11

Figure 1. Anne Lacaton and JeanPhilippe Vassal. Straw hut building near the river Niger, Niamey, Niger, 1984. Photograph by Anne Lacaton.

Transformation, Intensification 12

Figure 2. Lacaton & Vassal, Maison Latapie, Floirac, France, 1993.

Photograph by Lacaton & Vassal.

SYDNEY SCHOOL 13

Figure 3. Winter garden. Lacaton & Vassal, 59 Dwellings, Mulhouse, France, 2015. © Philippe Ruault.

Transformation, Intensification 14

Figure 4. Lacaton & Vassal, 59 Dwellings, Mulhouse, France, 2015. © Philippe Ruault.

SYDNEY SCHOOL 15

Figure 5. Lacaton & Vassal, 53 low-rise apartment units, SaintNazaire, France. © Philippe Ruault.

as programmed space, to promote relationships within spaces, to bring about pleasurable situations. This extra space is a non-defined space, free-for-use, added to the traditional spaces, just a response to the question of freedom (fig. 4).

Every dwelling must have a private outdoor space, such as a balcony, a terrace, or a wintergarden, to provide the possibility of living outside, of having a garden, as in a single house, inside the city. A dwelling must o er the inhabitant opportunities to move around. For example, consider the relationship between fluidity, mobility, freedom and appropriation. Instead of a standard dwelling, we can extend mobility, freedom of use, to allow appropriation. All rooms should have large doors opening to the outside to facilitate movement on the same level, inside or outside, just like a house.

Beam-column construction systems allow flexibility and economy. Instead of standard dwellings with load-bearing walls, windows, shear walls and no flexibility, we can have an open structure with a large span, free façade, and few columns, which allows flexibility, adaptability, capacity for evolution and economic construction and enables building larger at the same cost—130 instead of 65 square metres, for example. In terms of climate and energy saving, instead of two bedrooms with 65 square metres and a heavy external insulation façade, we can think of a temperate, intermediate space where people can live and work with passive energy saving and extra spaces for new uses. It means building larger—twice more—building double, at the same cost as a standard dwelling so it is a ordable for everyone.

Developing capacities. Building double to create other possibilities, other freedoms, new ways of inhabiting: to fully ‘inhabit’, to loosen norms, decompress space and allow this freedom of use to transform and expand the existing instead of demolishing it. To o er twice as much space to each person is a necessary and essential condition for any project that increases density. This means: a flat like a villa, more than the minimum function, extra space and additional facilities, with winter gardens, terraces, balconies, unprogrammed spaces accounting for at least 50% of the habitable surface (fig. 5). Our aim is to re-develop the concept of “villas,” “houses with a garden,” inside the city. The idea of luxury is therefore redefined in terms of generosity, freedom of use and pleasure. The most important point is to “build with,” which means that the starting point is the existing, and the starting point is extreme precision, the extreme kindness we need to show towards all that exists.

In a beautiful place close to the sea, the question was to consider whether it is possible to build on a plot with 50 pine trees and a beautiful sand dune.4 Is it possible to come, to build, but at the same time, not cut down a single tree and keep the shape of the ground, of the sand dune exactly as it is, instead of cutting down trees and erasing sand dunes? How is it possible to mix the systems, to say: We will precisely take care of each root, each branch, all the bushes on the site. We keep the shape of the sand dune, and we mix the structures of the forest and our new housing place. How is it possible to take the light from the reflection of the sun on the sea and bring it to the ceiling under the piloti on this corrugated aluminium to lighten the entrance under the house? How is it possible to keep the trees inside? How is it possible to make foundations without disturbing the roots of the pine trees and leaving the pine trees crossing the house and still moving with the wind inside the house? One pine tree in the middle of the corridor between the bedroom and the bathroom (fig. 6–8).

Just to propose incredible situations of sharing and mixing the quality of housing with the preservation of nature. This could be done for one house, or it could be done in another situation for a competition in the west of France close to a forest. How could housing projects allow nature to recover its place in areas where its quality and its importance have been reduced by the extension of the city? How can nature take its place again? This project was about 250 units of collective housing (fig. 9). How is it possible to leave the ground free, to leave enough space between the ground and the upper levels?

Transformation, Intensification 16

4 Lacaton & Vassal, Maison Cap Ferret, France, 1998.

SYDNEY SCHOOL 17

Figure 6. Section. Lacaton & Vassal, Maison Cap Ferret, France, 1998.

Figure 7. Lacaton & Vassal, Maison Cap Ferret, France, 1998. Photograph by Lacaton & Vassal.

Transformation, Intensification 18

Figure 8. Tree in corridor. Lacaton & Vassal, Maison Cap Ferret, France, 1998. Photograph by Lacaton & Vassal.

Figure 9. Lacaton & Vassal, Eco quartier, La Vecquerie, SaintNazaire, France, competition, 2009.

How to find ways, with minimum impact of the piloti on the ground, to leave enough light to make it possible for the trees to occupy the place that was reduced by the situation of a new building. How is it possible to mix these two systems—housing and nature? Finally, how can the responsibility of being an inhabitant involve the preservation of nature below the flats? How can we mix and intersect these situations of housing and the preservation of nature? It is about precision. Dealing with what is already there, “building with,” means an extreme precision, an extreme delicacy. And it allows us to derive maximum pleasure from the combination of situations, of housing and nature. Transformation, in all situations. Anne will continue.

AL

Transformation is an important issue for architecture and for urban planning today. It’s about “making do.” Transformation is about making better use of what we already have. We already have a lot: buildings, networks, roads. It’s important to consider the existing as a valuable resource and a great opportunity, instead of always seeing it as unsatisfactory. Every existing situation is an opportunity made of multiple elements, qualities, and capacities that can be integrated, reactivated and reused.

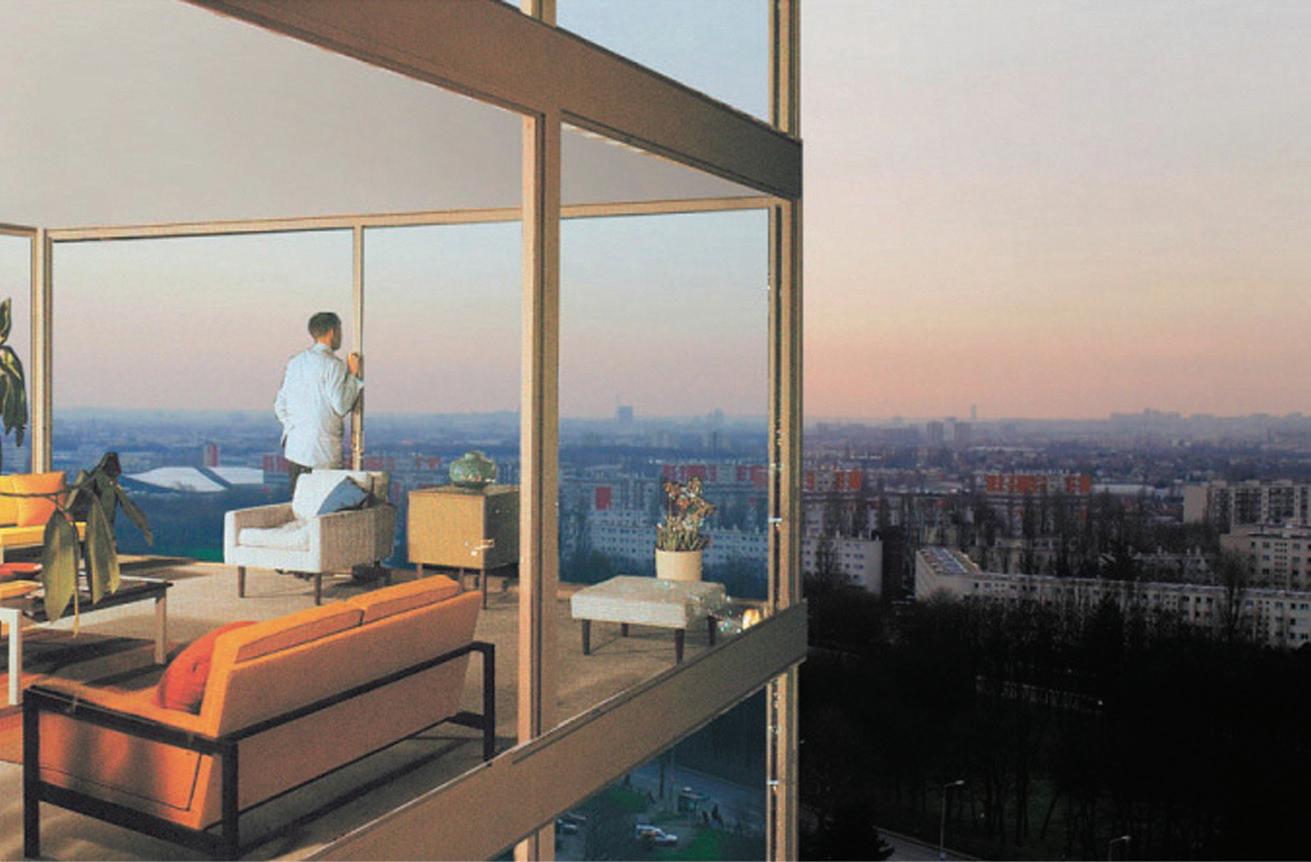

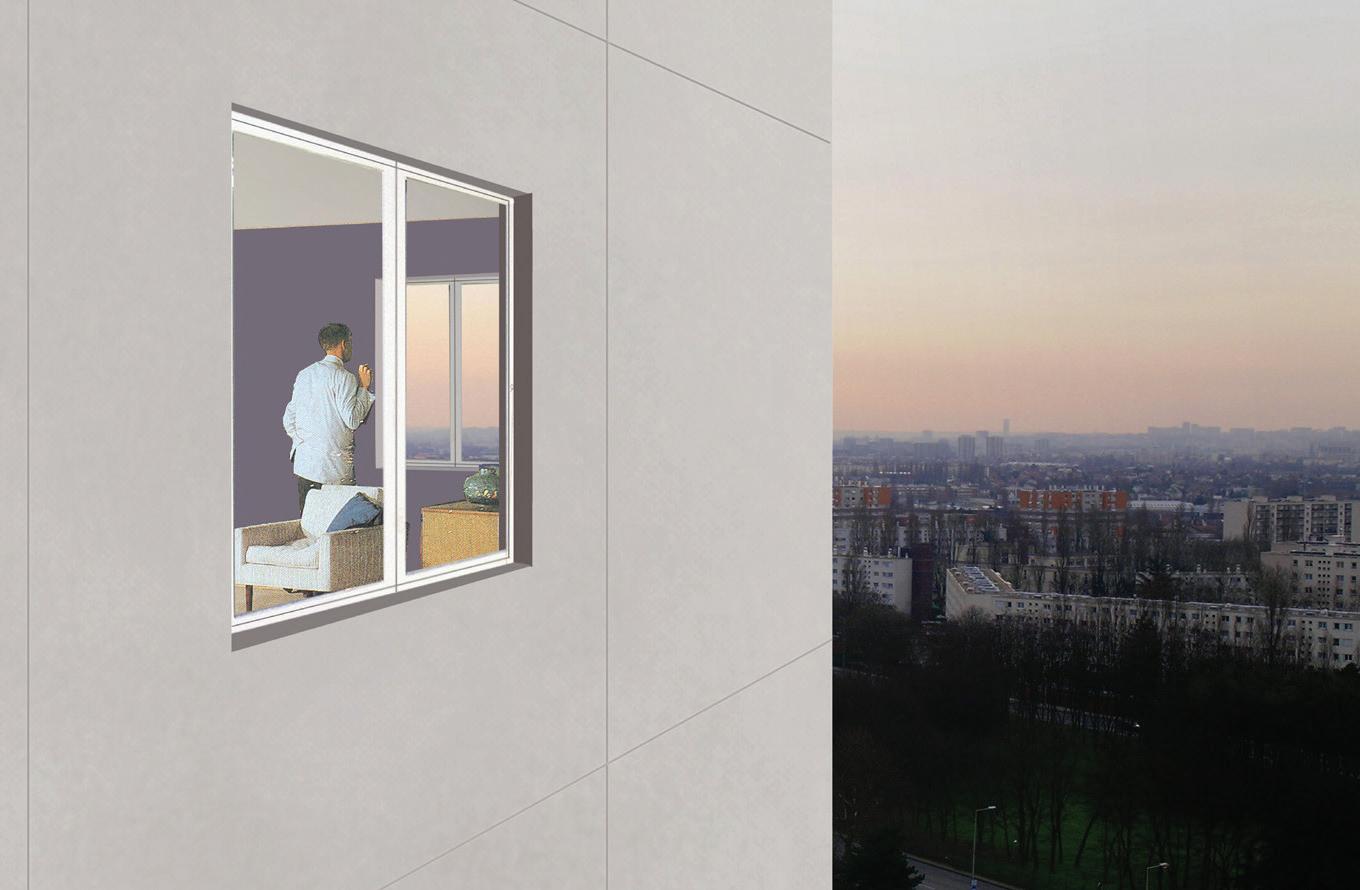

In the case of modern housing blocks, transformation is the opportunity to upgrade the quality, to extend living spaces, to increase pleasure and comfort, to save energy, to bring in more light, to do more with less, with and for the inhabitants.

Over the past 20 years, we especially studied the large modern housing developments that have been built on a massive scale in the suburbs of cities all over the world. At the time, they carried the vision of an optimistic future and the modern way of life, a ordable to everyone. But today, these places no longer represent a contemporary model of living in many cities, and the future is a big issue everywhere. In France, a massive national program of urban renewal was initiated around 2005 based on demolition and construction of almost 200,000 new flats. Our position towards this program was to say: never demolish, never remove or replace, always add, transform and reuse.

Here are a few numbers to compare the costs of these two situations in the French context. The minimum cost of demolition and new construction of a standard apartment of 200,000 units is €160,000 per dwelling. Transformation means extending life, more living space, non-standard housing, which according to some of our case studies costs about €50,000 per dwelling. It is important to see this economic di erence, but it’s not the only interest. Transformation is more ecological and, above all, it involves less waste of materials and less CO2, and the social impact—which is very negative in the case of demolition—is also lower.

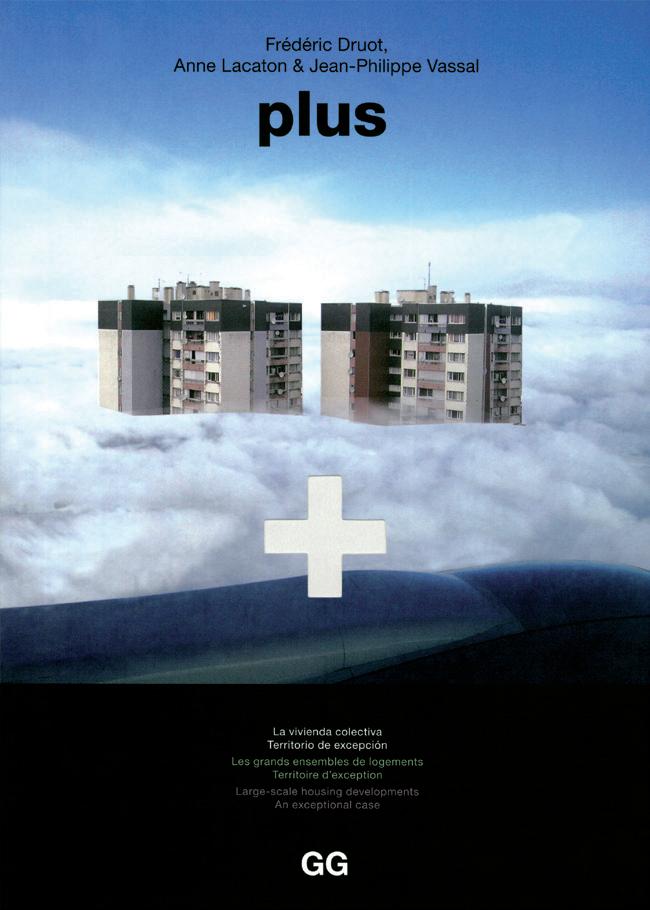

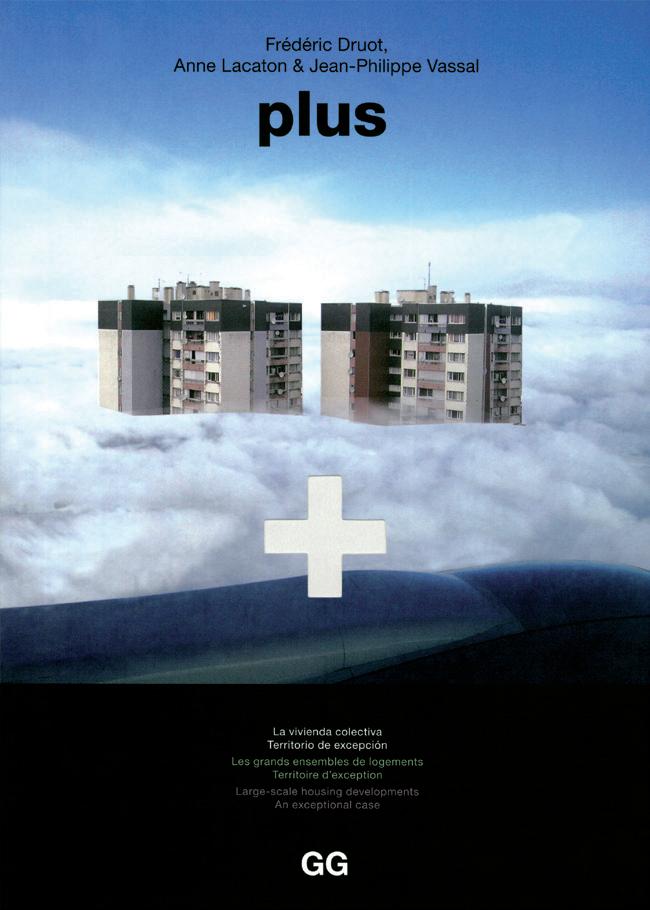

Facing this situation as architects, we took the opportunity to study it carefully. Together with a friend, Frédéric Druot, in 2004 we published this study, which we called PLUS, in which we analysed a number of cases of demolition and new construction from the program to carefully examine the potential of these situations, to carefully consider alternatives to demolition, and to make a transformation (fig. 10). The subtitle was Large Scale Housing Developments, an Exceptional Case. In it we talked about the great potential of these places if we carefully take the time and have the will to look at them positively. Our first observation was that the developments of the 1960s and 1970s were built very fast, with probably not enough care for the quality of housing. What we could imagine, was to take this situation and keep what was good and only add what was missing. What was missing in most cases was that the situation was not used as much or as well as it could have been. Just by opening the façade or creating balconies, a transformation could radically change this building into a more kind and a more inventive solution than demolishing it and rebuilding it elsewhere (fig. 11).

After this study we had the opportunity, but it took a long time because, in the end, we never really managed to convince the authorities to talk about the national situation.

SYDNEY SCHOOL 19

“never demolish, never remove or replace, always add, transform and reuse.”

Anne Lacaton

Figure 10. Cover of Frédéric Druot, Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal, PLUS: Large-scale Housing Developments, an Exceptional Case Barcelona: Editorial Gustavo Gili, GG, 2007. (Original in French from 2004).

Frédéric Druot, Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal, PLUS: Large-scale Housing Developments, an Exceptional Case. Barcelona: Editorial Gustavo Gili, GG, 2007. (Original in French from 2004).

Transformation, Intensification 20

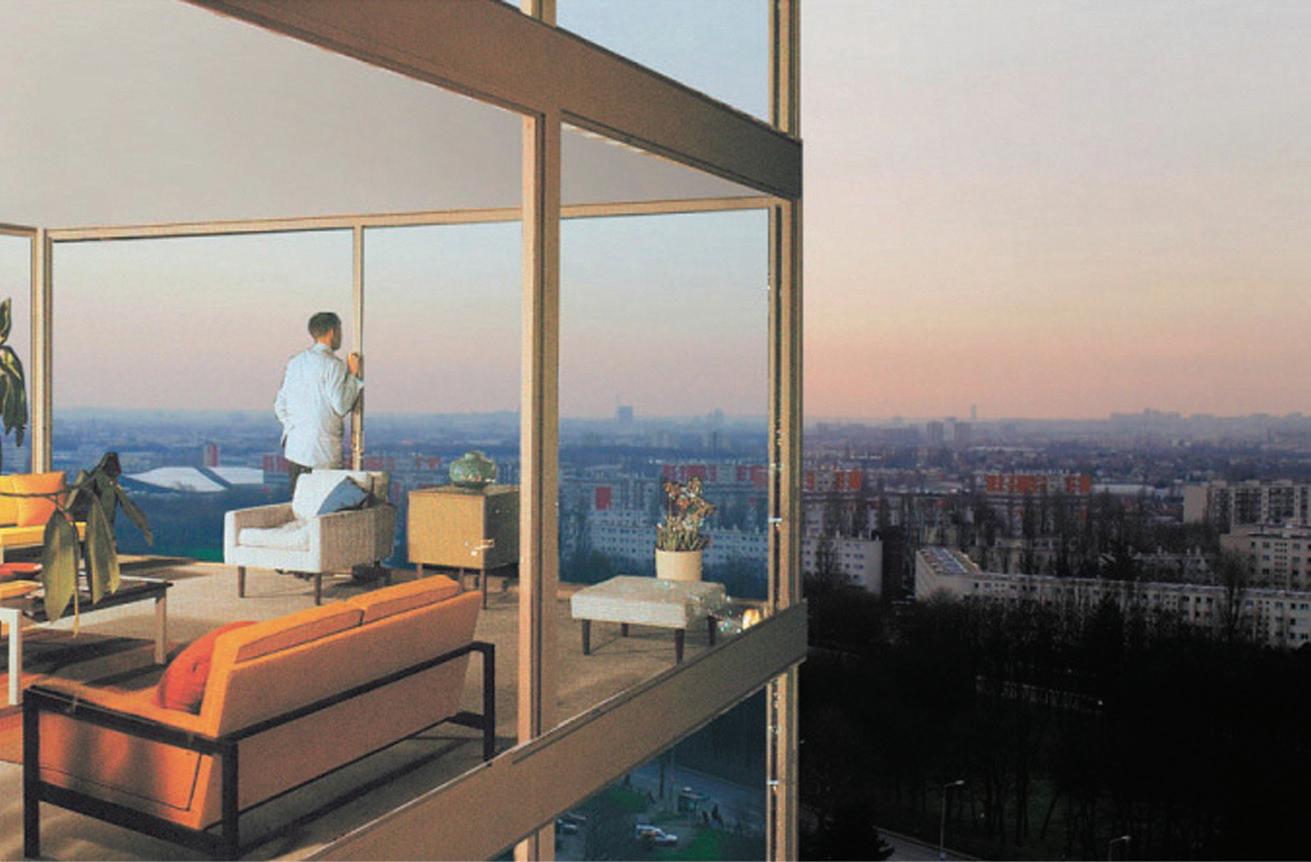

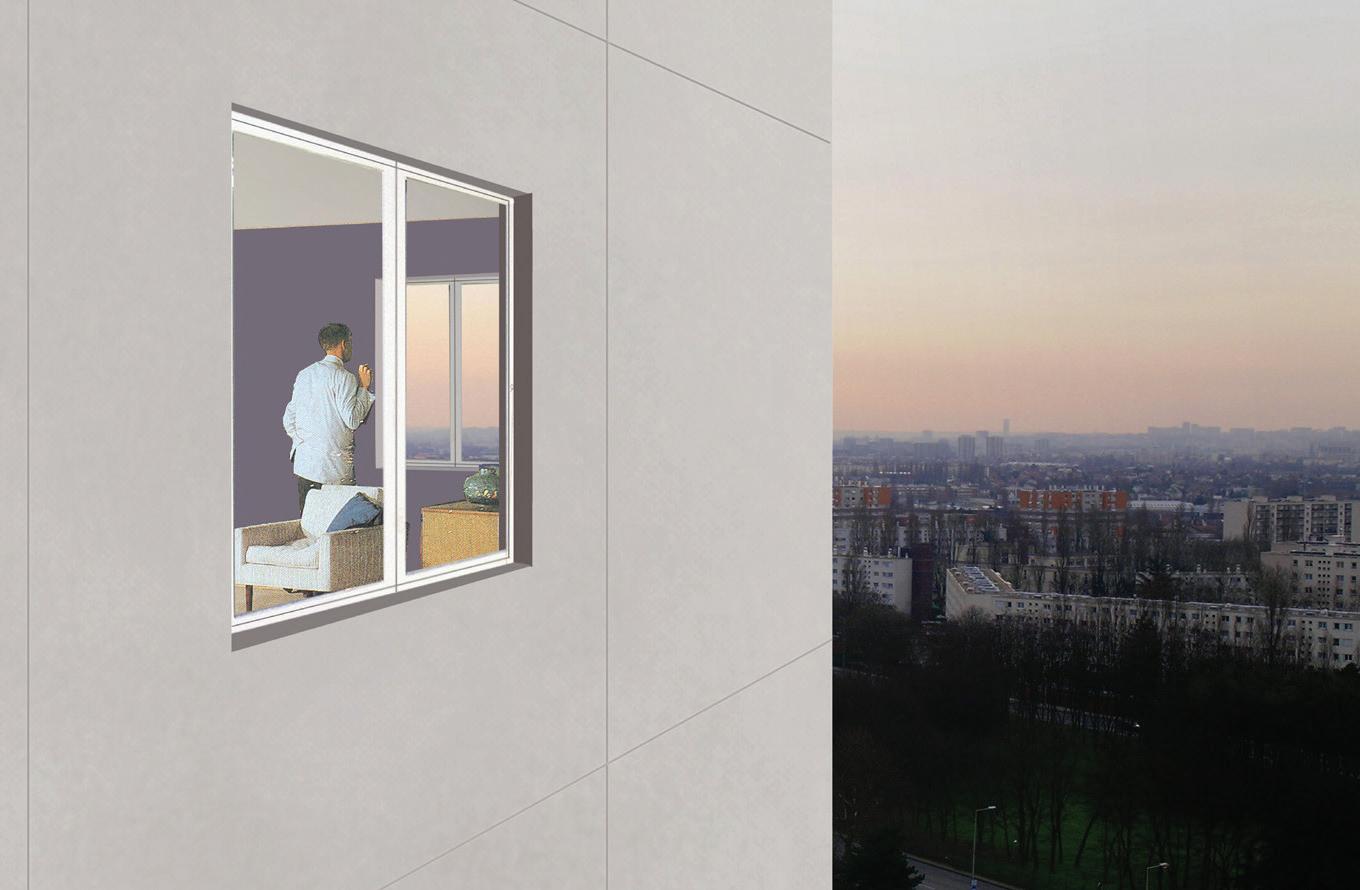

Figure 11. Series of collages.

Still, we were able to find here and there some owners who accepted this idea and commissioned us to do a project.

This is a project we completed two or three years ago in the city of Bordeaux, consisting of three housing blocks with 530 dwellings. These three housing blocks are part of a very typical modern development in Bordeaux (fig. 12). When this project was built with about 5000 dwellings, it was not entirely integrated into the city centre. So, it was a little bit, not rejected, but not much desired. Today, the situation has really changed, and it is very much a part of the city, including public transport and facilities. It’s a good place to live. Nevertheless, as part of the demolition program, the city planned to demolish and rebuild these three buildings with the idea of reopening the neighbourhood and reducing the number of dwellings in the area. But all these apartments are in quite a good location in the city, with very nice views. All apartments were occupied by people on low incomes, who found there a good situation for living. So, for the city of Bordeaux, which is rather low-rise and a city of stone, it is quite a prominent neighbourhood, but very close to the city centre. Finally, the director of the social housing company that owned these buildings managed to convince the city to keep them and to carry out a project of transformation. So, together with Frédéric Druot and Christophe Hutin—Christophe will give a presentation on another project tomorrow afternoon—we were able to do this project, and what we proposed was to appreciate this situation in the right way.

It is absolutely important not to remain outside, not to look at these blocks from a distance and observe that they are quite ugly, as is usually done, and not to hold on to this impression. But it is important to go inside and visit every dwelling, every person and, in a way, to reverse the lens through which we view it. It is a totally di erent situation that we can discover inside. We discover 530 individual situations, all of which have been given

SYDNEY SCHOOL 21

Figure 12. Existing housing blocks. Grand Parc, Bordeaux, France. © Philippe Ruault.

Transformation, Intensification 22

Figure 13. Situations. Lacaton & Vassal, Druot and Hutin, Grand Parc, Bordeaux, France, 2017. Photographs by Philippe Ruault, 2019.

SYDNEY SCHOOL 23

great value by the inhabitants themselves (fig. 13). It is absolutely important to come from this point of view and imagine that what appears like a single block from the outside, is in fact a house of many, many people and that all these people attach a lot of importance to their home. So, in terms of work, it is absolutely important to start with all these di erent situations inside, which the families have enriched by their own decoration, their own way of living.

The project that we proposed was to start from the values of what we saw inside and to make every e ort to ensure that all these situations could remain, not only after, but also during the transformation. What was missing in these apartments was a little more space, more surface, more air. In a really nice situation, with views all over the city, all over the river, all the apartments had very, very small windows, and very few had little balconies. So, something was missing—to give more air, more view, and more space for each dwelling. But it was important to do this for all inhabitants. So, we proposed to build an extension with all inhabitants remaining inside, so that no one had to move during the works, and then to renovate the inside according to the di erent situations as well as renew the systems, the electricity and the bathrooms. All this could be done in a very precise way.

The principle was to build an extension, which was prefabricated outside, consisting of elements of 4 metres by 7 metres. These elements could be placed on each level in front of the dwellings as a continuous extension with no individual situations. This kind of winter garden, this additional space, had two façades. Then we removed the handrails and all the existing façades to open it up as much as possible and to facilitate all the connections between the existing dwelling and the extension. A glass façade replaces the existing one and closes o the heated space. Outside, a movable, lighter façade closes o the winter garden.

In the early studies we also proposed the methodology of construction, which would demonstrate that all of this was possible while all the inhabitants remained inside. So, in fact there were two kinds of work: the work of the extension, which proceeded from the outside so that the inhabitants were not disturbed too much; then the interface, the moment we removed all the handrails and replaced the façade; and then the last finishes, including the interior finishes. This process was applied to all levels and to all apartments. Plus, on the rooftop we used the opportunity provided by these flat roofs to introduce additional larger apartments, which were missing in the typologies.

The transformation process of this 175-metre-long and 15-storey-high existing block allowed us to radically change the quality of housing, the comfort of housing, the pleasure of housing as well as the image of the building. With these winter gardens, we could also radically improve the energy e ciency of the building and cut energy consumption by more than half.

Regarding the process of extension, these elements were built two kilometres away, brought on a truck and immediately placed on the construction. All these elements are totally independent in terms of construction. This is why we could build these columns and the new foundations beforehand. Every day, about five to seven elements were built, with only two people guiding the element and one person in the crane. Then, the next level was prepared. It’s just attached to the existing building for the wind but, again, it is absolutely independent. Then, the new columns for the floor above are put in place.

Once a number of floors had been built, we could start the process of opening the façade. At that moment it becomes a bit more critical for the inhabitants, but the commitment was that the replacement of the façade would be completed in two days at the maximum (fig. 14). On the first day, the opening was made and on the second day the new glass windows were installed to close o the previously existing apartment, followed by the finishes for the winter garden and the opening towards the inhabited area. When opening the façade of the existing building, we first had to remove the window elements, which contained some asbestos, but we placed protection inside the apartment

Transformation, Intensification 24

beforehand so that life could continue. The process of opening the façade, deconstructing the handrails and the existing windows was completed at the end of the first day. On the second day, the frames and the new glass windows were installed. Then there was the issue of finishing the inside, but this could be done another time, and the family could start to use the place again (fig. 15–18).

So, from the existing situation of a small window that became a large glass window, it was just a matter of the handrail. We did not disturb the structural system of the existing building in any way, because all these elements were not really part of the structure, except for the handrails. Then it was amazing to see how the 500 new situations created by these winter gardens were transformed in fascinating and surprising ways by the creativity of the inhabitants. Very quickly, the families used the space in many, many di erent ways. The transformation of the quality of this housing is absolutely radical, and the building has begun a new life of around 50 years with very good technical and sustainability elements. So, we have gone from an existing to a completely new situation.

You can see here the double façades of the glass windows with double glazing, which is insulated, the thermal curtains that allow the internal space to be kept warm in winter, the winter garden, the interior of the winter garden (which is not heated) and the façade of the winter garden, which can be opened wide in summer to become a terrace, which is also very e cient for summer comfort (fig. 19). These three metres inside provide a good amount of space for furnishing, which again is totally di erent from family to family. In addition to the winter garden, there is a one-metre balcony, which makes it possible to go outside and avoids a straight façade. All these internal appropriations were really much better and much more surprising than we had in mind (fig. 20 & fig. 21).

This intervention, which began from the inside, from improving the quality of housing, radically changed the existing building and has given it a second life. The new apartments on the roof also create amazing situations on top of these buildings. Using the potential of these flat roofs enabled us to add 10 apartments to this large development. Moreover, the transformation of the general situation was also a benefit for the whole city.

SYDNEY SCHOOL 25

Figure 14. Transforming. Lacaton & Vassal, Druot and Hutin, Grand Parc, Bordeaux, France, 2017. © Philippe Ruault.

Transformation, Intensification 26

Figure 15–18. Sequence of construction. Lacaton & Vassal, Druot and Hutin, Grand Parc, Bordeaux, France, 2017. © Philippe Ruault.

SYDNEY SCHOOL 27

Figure 19. Winter garden. Lacaton & Vassal, Druot and Hutin, Grand Parc, Bordeaux, France, 2017. © Philippe Ruault.

Transformation, Intensification 28

Figure 20. Transformation. Lacaton & Vassal, Druot and Hutin, Grand Parc, Bordeaux, France, 2017. © Philippe Ruault.

SYDNEY SCHOOL 29

Figure 21. Roof top apartment, Lacaton & Vassal, Druot and Hutin, Transformation, Grand Parc, Bordeaux, France, 2017. Film Still from the documentary Constructing Escape: A Story about Air, Void and Light, Anne Lacaton and JeanPhilippe Vassal directed by Karine Dana, 2019. © Karine Dana.

Just a few numbers show that this situation is absolutely a ordable. We can say that 100% of the existing has been conserved, 20% through substantial renovation like the hallways, elevators, bathrooms and 80% through minor renovations like some painting and new flooring where it was needed (fig. 22). We added 53% of surface area, an average of 50 square metres per dwelling, including winter gardens and balconies but also sometimes interior spaces. Due to the winter gardens, careful change to the systems and part of the insulation where it was necessary, the primary energy consumption was reduced by 60%.

During the works, 100% of the building was continuously occupied—no inhabitant had to move out. And there was no rent increase for the occupants. It is social housing and the rent plus charges remains the same after the transformation. Whereas, before the project, the city estimated the cost of demolition and rebuilding at €160,000, the construction cost of the transformation was €50–55,000 net. It is also interesting to note that while it is a public social housing company, there was only a very small amount of public subsidy (20%) and 80% was funded by the social housing company Aquitanis itself.

It is worth mentioning that this is not a unique case. All over the city we have a large number of such situations where, with a situation-by-situation, case-by-case strategy, we can achieve this improvement of housing quality everywhere. This can also be used for densification, because sometimes there is land available with potential for construction. But again, it is only a case-by-case strategy from the inside that allows such an approach to be taken and, for us, it is important to see that this is the way to think in the future.

This is the last slide, thank you very much. Now we can answer questions (fig. 23).

Transformation, Intensification 30

Figure 22. Transformation. Lacaton & Vassal, Druot and Hutin, Grand Parc, Bordeaux, France, 2017. © Philippe Ruault.

SYDNEY SCHOOL 31

Figure 23. Rooftop apartment. Lacaton & Vassal, Druot and Hutin, Grand Parc, Bordeaux, France, 2017. © Philippe Ruault.

CL

Thank you so much, Anne and Jean-Philippe. Can you all hear me?

JPV

Yeah, it’s okay.

CL

Okay, so we have some time for questions. I can open it up to the floor. For the people listening online, remember to type your questions into the chat and Kate Goodwin is going to be feeding us questions from the online audience. And also, to welcome Hannes Frykholm who is joining us from Stockholm. As Robyn mentioned, he—when he arrives in August—will be our Rothwell Postdoctoral Associate and helping to guide the research agenda over the next three years.

HF Yes.

CL

So, are there any questions? Anybody got a burning issue? Maybe I can start things o then. Anne and Jean-Philippe, I really appreciate this connection, extension and also the critique of modernism in your architecture and urban design. For example, you question Le Corbusier’s conception of tabula rasa but connect with such strategies as the Dom-Ino frame and the architectural promenade in your work and I wondered if you could say a little bit more about this strategy of transformation in terms of constructing one’s position. You emphasise this word a lot and I’m interested to hear more about that.

JPV

Yes, perhaps we could say, to be clear and simple, it is a fact that we totally agree with the architecture that has been developed through the modern movement. But at the same time, we are totally against the urbanism that has been developed by this same architecture. So, we think that the question of quality, comfort and pleasure, which were given by the principles of architecture, could be done today in a completely di erent way in terms of urbanism. No longer an urbanism from above, a top-down system but, on the contrary, a bottom-up system taking the existing city as the starting point—the existing city with its di culties, with its problems, but also with its qualities, with its richness, with the people, with the trees, with nature—taking it as a principle of a starting point. How, finally, can modern architecture be adapted to the continuity and the improvement of the existing city? For us, it is no longer a question of designing a new master plan but, rather, working with precision on particular situations of the existing: What is missing? What is the problem? How can we keep this tree? How can we keep those trees? How can we take care of the social relations? It is this precision that is absolutely necessary. So, to answer your question, we totally agree with the architecture of the modern movement, but completely reject the urbanism that developed as the continuity of this architecture.

HF

I think it’s something we’ve also many times returned to in our discussions prior to this Symposium. It seems like it is impossible to think about a ordable housing or improving the quality of housing without thinking about the project of the city at the same time. So, there is no longer a tabula rasa but there is a question of densification all the time. Densification is something that actually brings more space to the city or makes the city bigger in a sense. I think that is a really essential theme here to highlight.

Transformation, Intensification 32

Discussion

JPV

Absolutely, but there is also the question of a ordability, which is really important. The question of economy, how it is possible to spend less money when considering the transformation of the city. But there is another extremely important point, which is ecology, given the energy we are wasting to demolish and rebuild, when we could be improving some situations. If we make the comparison, it is enormous. If we have some intentions today in terms of sustainability and ecology, we cannot continue with this idea of making tabula rasa or demolitions in relation to the existing city.

AL

It’s also clear for us—as we said in the beginning—that housing is an elementary unit that makes up the city. However, it should not be understood as a mass of housing, but rather as one plus one plus one plus one. Because in fact it’s the only condition to think about: What is the quality for everyone, what is the quality of living for everyone? Probably that is something, which was a little bit neglected in the big housing developments of the 1960s and 1970s. They built large blocks, but not really with great care for how life was inside. Today we have the opportunity to rethink that, instead of saying that the whole system was bad, was wrong, and that we should replace the system with another one. We don’t agree with this idea of always replacing systems by new ones, but much more with a strategy of making do, of changing a system by adding another one—something which is more complex, and which also corresponds much more with the possibility of doing it with the inhabitants. By demolishing, for example, inhabitants are moved to other neighbourhoods, and that has a great social impact, because most people like their neighbourhood and would like to stay. But on the other hand, it is also important to introduce a mix, to attract new inhabitants. This is why we are convinced that the combination of good housing quality, improving the quality of existing housing and densification absolutely work together.

CL

Thank you. I think we have a question from the chat.

KG

We’ve got a lot of questions flooding in, actually—a lot of excitement online. There’s a question from Marjeerah who’s asked, “How was the project idea sold to the housing organisation?” I imagine she’s talking here about Bordeaux. Was it ideological, aesthetic— was it about cost or not needing to move the residents that really was the compelling argument for them as a client?

JPV

I think in Bordeaux they didn’t take very much care of these three blocks during the last 15 years, because there was probably a plan to demolish them. So, the living conditions were decreasing and decreasing. There was hope with the appointment of a new director of this social housing organisation who was looking at the economy of the situation. There was no more bank debt on these buildings, because they were built in the 1960s and there was a small amount of rent coming in every month. In fact, demolishing these buildings would have meant immediately a loss for him. The question was also not to be satisfied with a standard refurbishment that would just make some little changes to the situation. Then it came to the point that a kind of metamorphosis, a real transformation, could be interesting. And, as the politicians, the municipality, were not so confident about this project, he himself raised the possibility with a bank to get a new loan, saying that in the next 20 or 30 or 50 years he will have the benefit of rents that will allow this transformation to be made. As he was also responsible for the rents, he was able to slightly increase the rent due to the more economical additional charges. Because of less energy consumption and lower

SYDNEY SCHOOL 33

5 In this instance, the French term mixité was retained in accordance with the original wording. The term is frequently translated as “diversity.”

charges, rents could stay a ordable for each inhabitant. These were the conditions within which the project was implemented. What I find interesting is, even though it is a social housing project, it’s certain that, in 10 or 20 years, this building will still produce good living conditions for everyone. I don’t know if it will still be social housing then, or perhaps there will be new systems. But we really believe in the possibility of mixité; and it is very important to understand that mixité can only happen in the best situations.5

AL

It’s clear that economy is not the only important argument. It’s clear that it is also about how we can improve, in the best way, the housing conditions. This is of course our highest aim. But the economy is very important as well because, if you remember, the di erence between the cost of the transformation of such a building and what it would have cost to demolish and rebuild is about one-third. That means, with the same amount of money, we could do three such buildings and improve a lot more a ordable housing in the city. Economy is something very important, not to reduce, not to constrain, but the opposite, to give more possibilities and more opportunities for any project. This is an important point in these processes of transformation, in addition to ecology and sustainability. All calculations show that the savings in CO2 and the savings in material are significantly higher for transformation projects than for demolition and rebuild. All of these aspects are very important. However, the primary objective is to provide good housing.

JPV

And perhaps just to complete a little bit. It is clear to see that when you have ‘1’ and you add 50% to ‘1,’ at the end you have 1.5. When you have ‘1’ and you demolish ‘1’ and you rebuild ‘1,’ at the end, you only have ‘1.’ This is also the ambition of addition. With additions you have more than with the standard, and this is why it is so important for us to say that by adding, we end up with much more than the standard is able to provide today.

KG

There’s lots here, there’s one from Tristan Bergmoser who’s asking about the perception of some of these modernist social housing estates, which are often perceived as ugly, and how that stigma can be overcome.

JPV

You can see the images. We believe—we have been working now for many years—we believe in the fact that what is good is beautiful. This means that when it is possible to work for the pleasure of living for everyone and when this pleasure is visible, when you no longer see spaces of constraints, of di culties, the result is that there is a change in the image of the building. We really believe in this situation. In fact, today we need to be confident in the inhabitants. It’s only because they are happy in a place that they will probably do some gardening on their balcony. This balcony, when you look at it from outside, will change the image. We really believe that a beautiful building is a good building.

GJ

Hello there, it’s Graham Jahn from the City of Sydney, Director of Planning. I just wanted to say that when I had a chance to visit the building with Christophe, I was struck by the economy of detail that you’re able to infuse into the building, such as continuous sills or service mounted conduits or freestanding footings or even the modular construction. It was paring back and managing the costs with every move, to maintain that expertise and the sense of space but also not wasting money. I could see that in every move, so I think it’s important to comment on how this was achieved through real strong attention to detail, but also not fussing unnecessarily around detail as well. I think that’s an important point.

Transformation, Intensification 34

“we believe in the fact that what is good is beautiful.”

Jean-Philippe Vassal

JPV

Yes, I think you’re absolutely right. I think when we talk about the transformation of the city, we have to go immediately into the details, into the precision of the complexity of the city, and we have to find the right answers to these precise questions. By the way, this is a totally di erent approach, because with this precision we can immediately know about the economy of the city. If we look at the city from very far away, we only have to provide some budgets and these budgets are probably sometimes 50% or two times or three times too much considering the reality of the existing situation. This is how we think about this big change. We can imagine that it is no longer urban questions that define architectural answers, but we think that it is architectural answers that can develop the continuation of the city, the articulation of urban questions and urbanism.

AL

Just to add to these comments. In such a project when the decision is taken to do the transformation while everyone stays living inside, then it’s clear that at this moment it’s important to develop a really new strategy of design with a number of new criteria coming into consideration. It forces one to especially take care of how to make things very accurate, very precise but also very simple. In a way, having these constraints is a great benefit for the project. One could think that it’s a big constraint and that it would be easier to make such a project while the building is empty. We had a di erent experience. The experience with the building remaining occupied by all inhabitants was much more successful because it forces one to anticipate a lot of problems in the design that normally you wouldn’t. We had to design precisely and to place ourselves much more inside the situation and to understand more things than in a normal project.

CL

Do we want to take one more question from online?

KG

There’s a question and observation that single-title renewal projects are far simpler than multi-title residential renewal projects and so Kieran here is asking how can forms of consensus be reached when working with large diverse groups of people in large buildings.

JPV/AL

Sorry… Could you repeat?

KG

Yes, it’s a question about an observation that you were dealing with. If the building has many di erent owners rather than a single owner, how do you reach consensus with such a diverse group of people, rather than having single titles.

JPV

Yes, it’s also why in …

AL

It’s an issue.

JPV

It’s a really important issue, but I think it’s part of the complexity. What we really believe is that each situation is di erent. Working with the same approach in each situation we should find the answers. This is also why, in the fifth session of this Symposium, we will have speakers who will talk about the cooperative system in Switzerland and the Baugruppen

SYDNEY SCHOOL 35

“We can imagine that it is no longer urban questions that define architectural answers, but we think that it is architectural answers that can develop the continuation of the city, the articulation of urban questions and urbanism.”

Jean-Philippe Vassal

in Berlin. The question at any one moment is to think how we can adapt to these di erent situations. For example, with Frédéric Druot we have studied the possibility of applying these techniques to private systems with multiple owners. In many situations, we see that these buildings were built in the 1960s and today the land is very, very expensive. So, in addition to the improvement of the existing flats, we can also see the possibility to create densification, sometimes of 5%, sometimes of 10%, sometimes of 50%, as in a project we will show in two days. Through this addition of new flats, we can find the economy that will allow the transformation and the improvement of the whole situation. It is probably a challenge to work with multiple owners, but we really believe that all these situations are interesting and that, with precision and attention to each situation, we can find solutions.

AL

It’s clear that a situation with only one owner is very di erent. In France, we have a lot of social housing, which is public social housing with just one owner. But on the other hand, because it was a very large unit of housing, the loan required approval from the tenants. They had to vote once they were aware enough of the project and had visited a prototype we did. For one week, we were present in the prototype to explain the project and its benefits and also to talk about the issue of rents, which was a crucial question for the inhabitants. Afterwards they had to vote on whether they agreed with the project or not. Even though it’s public housing, if there is no majority, the project cannot be done. We also did important work in meetings on di erent topics to explain the di erent aspects and benefits of the project, including the construction phases and how the project would be carried out. For example, we explained that the work would be done staircase by staircase, so that it was not one huge construction site where we would start works everywhere. This meant that not all inhabitants were impacted by the construction during the whole time but, say, over a period of five months. It’s clear that all these projects require very specific work with the inhabitants. It’s important to recognise that the inhabitants have to be part of the process—not to define the project, not to make all decisions but to talk about their skill of inhabiting. In the case you mentioned, when the inhabitants are also the owners, then they also have to make decisions. For now, we haven’t succeeded in getting a commission for such a project. However, we really thought about it and did many simulations, and we think that it might be a little more di cult and a few percent of the multi-owners could be against it, but probably with special care it would be possible to succeed.

JPV

What is clear—because it also happens in France—with these multi-owner situations we see that the situation is sometimes very, very bad because you have no social housing company that takes care and year after year the situation becomes worse and worse and worse. So, there is clearly a position to take: Should we wait until it is so bad, or should we try to do something?

AL

Yes, and also the cities have no interest in allowing a situation of so much di erence to develop. I don’t know if it is the case in Sydney, but in France it’s clear that most of the multi-owner ownerships are poorer than public ownerships. And this is most of the time. For example, they cannot a ord even €50,000 to transform as we could do with public subsidies. As Jean-Philippe explained, we did this study, for example in Paris we studied more than 140 di erent such situations to be able to find the economic model that would allow this form of ownership to access the money to pay for the transformation. This is also part, an important part, of the task: to think about the economic model to develop these projects.

Transformation, Intensification 36

CL

Do we have one more question here? And maybe if we just have one more question and then draw it to a close because we’re already over time. The great thing is that we can continue talking over the next few days.

BS

My name is Bridget Smyth, I’m the City Architect at the City of Sydney and I’m curious whether alongside the extraordinary transformation of the “home” that you’ve described today, there’s a complementary transformation of the spaces between these three buildings and whether or not there’s an investment in the kind of public life, the public space, the communal life, the civic amenity that makes this community. Could you talk a bit about that because you talked quite a bit about the shift in imageability and I’m wondering about the neighbourhood, the other scale, and whether there was a transformation in that area as well.

AL

This is a very, very important question. Because when we did the competition, it was part of the brief to also work on the close neighbourhood, and to make a proposal explaining how the transformation of the building could also influence the quality of this neighbourhood. In the competition, we proposed, for example, to strengthen the ground floors with a kind of plinth, which would make a much better connection between the public space and the private space, and also some extensions of the public space. Because it’s clear that it’s important that all of these things work together. But eventually, when we started the project after the competition, the municipalities decided that the public space would be done by someone else. Because in France it’s quite often that, ultimately, the architects do the buildings and the landscape architects, or the urban planners, do the public space. So, we couldn’t push for this opportunity to also think through the lower part of this building, which is so important because that’s where the critical relationship between housing and the city happens, which is a weak part in the modern developments. Normally, there’s nothing happening on the ground floor, and this is a part that should be strengthened with more public equipment to make a better connection.

JPV

Yes, but if we look at the situation in France, for many years the policy for urban renewal has only been focused on public space and never took into account the housing situation. And we really believe that it should not be disconnected. We think that the quality of individual space is the condition for a good collective life outside.

CL

Maybe that’s a great point to wrap it up and to think about how these conversations could continue. Tomorrow we’re going to be looking at some interesting innovative models from Victoria, and it’s interesting because some of those models actually draw on experiences with the Baugruppen and the Spreefeld projects that are mentioned in the last session that Anne and Jean-Philippe referred to. So, hopefully we can draw all these things together and continue the conversations in person and also online. But I’d like to thank Anne and Jean-Philippe very much, as well as you all and the online participants for taking the time this evening and I hope that we can continue these conversations in a really productive way within the city. So, thank you very much.

JPV

Thank you very much.

SYDNEY SCHOOL 37

“We think that the quality of individual space is the condition for a good collective life outside.”

Jean-Philippe Vassal

Anne Lacaton & Jean-Philippe Vassal, 2021 Pritzker Architecture Prize Laureates, established Lacaton & Vassal in Paris in 1987, and have since demonstrated boldness through their design of new buildings and transformative projects. For over three decades, they have designed private and social housing, cultural and academic institutions, public space, and urban strategies. The duo’s architecture reflects their advocacy of social justice and sustainability, by prioritising a generosity of space and freedom of use through economic and ecological means.

Further Readings

Druot, Frédéric, Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal. PLUS: Large-scale Housing Developments, an Exceptional Case. Barcelona: Editorial Gustavo Gili, GG, 2007.

Lacaton, Anne and Jean Philippe Vassal. Freedom of Use. Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2015.

Lacaton, Anne, Jean Philippe Vassal, Fernando Márquez Cecilia, and Richard C. Levene. Lacaton & Vassal: 1993–2017. Madrid: El Croquis, 2017.

Lacaton, Anne, Jean-Philppe Vassal and Enrique Walker. Moisés Puente (ed.). Lacaton & Vassal: Free Space, Transformation, Habiter. Cologne: Walther Koenig, 2021.

Transformation, Intensification 38

Transcripts of the 2021 Rothwell Chair Symposium | Lacaton & Vassal

Living in the City: Exemplary Social and A ordable Housing Design

Sydney School of Architecture, Design and Planning

Transcript Session 1

Transformation, Intensification

Edited by Maren Koehler and Catherine Lassen

Rothwell Co-Chairs: Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal

Rothwell Coordinator and Symposium Co-Curator: Catherine Lassen

Architectural Chair Project Manager: Sue Lalor

Design: Adrian Thai

Editorial Assistance: Sophie Lanigan

Copyeditor: Cherry Russell

ISBN: 978-0-6455400-0-0

Lacaton & Vassal and the Sydney School of Architecture, Design and Planning

Rothwell Chair Symposium, April 27–29, 2021

Chau Chak Wing Museum, University of Sydney & online

Published by the Sydney School of Architecture, Design and Planning, University of Sydney, 2023.

Copyright: Sydney School of Architecture, Design and Planning. Copyright of the content of individual contributions remains the property of the named speakers (authors). Other than for fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 and Copyright Amendment Act 2006, no part of this publication may be reproduced by any process without the prior permission of the editor, publisher and author/s.

The Sydney School of Architecture, Design and Planning gratefully acknowledges permission to reproduce the copyright material in this publication. Every e ort has been made to trace copyright holders and obtain their permission. The Sydney School of Architecture, Design and Planning would appreciate notification of errors or omissions that will be corrected in future versions of this publication. Electronic versions of all five session transcripts are available for download: https:// rothwell-chair.sydney.edu.au/events/lacaton-vassal-rothwell-chair-symposium-2021/

We gratefully acknowledge all the named speakers (authors) and Symposium organisers for their contributions to this publication. The Rothwell Chair Symposium and recorded transcripts have been made possible by a gift from Garry and Susan Rothwell, which established the Rothwell Chair in Architectural Design Leadership at the University of Sydney. We wish to thank them for their generosity.

Editorial note

Acknowledging the diverse contributions to the Symposium, which at times varied in style, the editorial process aimed for a readable version, while still capturing the voice of the speaker. The guiding principle in this process of translation from spoken to written word was to make minimal interventions to retain meaning and conversational tone, while ensuring text flow. A final copyediting process and editorial review in consultation with the main speakers of the Symposium resulted in the document at hand. The visual material comprises a selection of images that were presented at the Symposium. Supplementary details, further readings and cross references to the respective parts in the video recording have been added in the notes.

SYDNEY SCHOOL 39

Cover image: Lacaton & Vassal, Druot and Hutin, Grand Parc, Bordeaux, France, 2017. © Philippe Ruault.

ISBN: 978-0-6455400-0-0