Re-thinking Housing Models — Victoria

Moderator: Roderick Simpson

Speakers: Clare Cousins, Quino Holland, Rob McGauran

RS = Roderick Simpson (moderator), CC = Clare Cousins (speaker), QH = Quino Holland (speaker), RM = Rob McGauran (speaker)

5 Abstract

6 Introduction

Roderick Simpson

6 Nightingale Village

Clare Cousins, Clare Cousins Architects

17 393 Macaulay Road, Kensington Quino Holland, Fieldwork

30 Ozanam House: Accomodation and Homelessness Resource Centre Rob McGauran, MGS Architects

39 Discussion 46 Bios

Re-thinking Housing Models – Victoria 4

Abstract

Session 2 focused on contemporary a ordable housing projects in Victoria, Australia. Three Melbourne-based architects, Clare Cousins (Clare Cousins Architects), Quino Holland (Fieldwork, co-founder of Assemble) and Rob McGauran (MGS Architects), each presented a project that reconsidered architectural, social, environmental and economic questions associated with a ordable housing.

Clare Cousins introduced the Nightingale Village project, which comprises six buildings designed by di erent architectural firms. She outlined the unusual realisation process, whereby she and a group of architects, designers, clients and individuals provided the seed funding to initiate the project. Quino Holland presented Fieldwork’s design for Macaulay Road in Kensington, Melbourne. This project follows the so-called Assemble Futures model, which seeks to provide an alternative path to home ownership. The project includes a variety of common spaces inhabitants share, such as a workshop, a lending library, and so forth. Rob McGauran introduced MGS Architects’ design for Ozanam House, a homelessness resource centre o ering a variety of short-, mediumand long-term accommodation types as well as shared communal spaces and amenities.

The session showed how, in Australia’s highly financialised housing and real estate market, the issue of a ordability has led architects to venture into new roles in an attempt to invent alternative systems involving new models of financing and of architectural practice. In these projects, architects acted not only as design architects but, simultaneously, as investors, developers and community organisers. The three projects proposed alternative ways of living, questioning and circumventing the dominant logic of the market and the classic roles of architects, investors and developers.

The discussion highlighted how such projects, in conjunction with academic research, could provide the basis for important policy changes in Victoria. For example, the definition of a ordable housing as essential infrastructure allows for broader access to public funding. At the same time, the discussion revealed the important role of actors such as not-for-profit organisations and philanthropists in the development of alternative, a ordable housing models that can resist the pressures of the market.

SYDNEY SCHOOL 5

RS

Ready to go. Hello everyone, thank you very much for joining us here at the Lacaton & Vassal Symposium, which of course is possible through the philanthropy of Garry and Susan Rothwell—you may have seen the session last night. To begin proceedings, of course, I’d like to acknowledge and pay respect to the Traditional Owners of the land on which we meet, the Gadigal people of the Eora Nation. It is upon their ancestral lands that the University of Sydney was built, and as we share our own knowledge, teaching, learning, and research practices within this University, we may also pay respect to the knowledge embedded forever within the Aboriginal Custodianship of Country. Very minor housekeeping, the session is being recorded, which means it will be available more broadly, which is wonderful. And for those of you who’ve joined us here in person today, in the case of emergency, we will be directed by the museum sta

I’ll just briefly introduce our three speakers, if you haven’t seen their bios in the documents that have been provided earlier. Because of the nature of the Symposium, it probably makes most sense for those presenters to talk about their background as a way of introducing their practice. In any case, they know their practice much better than I, and usually people are a little bit resistant to talking about their achievements, but I think that’s a way that they might introduce themselves, hopefully.

First of all, we’re going to have Clare Cousins, who established her Melbourne practice, Clare Cousins Architects, in 2005. She’s been engaged in projects large and small. The studio has a particular interest in housing and projects that nurture community. Not insignificantly, Clare is a Life Fellow and past National President of the Australian Institute of Architects.

Our second speaker, Quino Holland, is an award-winning architect and director of Fieldwork. Quino has worked in the industry since 2001 on large and complex mixed-use, commercial, multi-residential and cultural projects. From 2011 to 2019—which is probably most significant in the context of this Symposium—he co-founded and was design director of Assemble, a real estate development group focused on projects where design, community and sustainability go hand-in-hand. I say particularly relevant because one of the things I think is going to come out of the discussion is this notion of expanded practice and changes in practice and changes in the nature of architectural practice in general.

Finally, we have Rob McGauran, who has kindly joined us from Melbourne—thanks Rob. Rob is a founding director of MGS Architects and leads the master planning design advocacy and urban design disciplines in the practice. He’s also a Professional Fellow at the University of Melbourne, an Adjunct Professor at Monash University and a board member of the Lord Mayor’s Charitable Foundation. We’ll be talking later about the significance of that charitable work and the outreach beyond architectural practice as well, Rob. So, without further introduction—Clare, would you like to take control of the screen and introduce yourself?

CC

Great, thank you very much. It’s lovely to be here. I shall start showing my screen. I don’t think there’s much more to introduce about practice, you’ve given a good enough introduction, thank you for that.

I’ve been asked to talk about the Nightingale model today, but firstly I would like to acknowledge the Wurundjeri people who are the Traditional Custodians of the land on which I present today. We pay respect to Elders both past and present of the Kulin Nation and extend that respect to other Indigenous Australians present.

I started the practice about 15–16 years ago and for the first 10 years it was predominantly made up of single residential alterations and additions and new housing projects. So, what makes good housing? Aspect, outlook, private open space—I think there’s a bit of an obsession with everyone having their own private open space in Australia. Light

Re-thinking Housing Models – Victoria 6

Roderick Simpson Introduction

Clare Cousins Nightingale Village

new

and ventilation. Flexibility, we think, is really important, and how spaces can have multiple functions. Certainly, long lasting and low maintenance, from a sustainability point of view and also, I suppose, from being easy to look after. More broadly, it’s also having somewhere local to shop, places to play. A great public realm makes places feel sociable and safe— feeling safe is also important. And a ordable to live in and run. A sense of community and having good neighbours, a place with an identity where people feel they can belong. Diversity, shared values, combat loneliness. And sustainable housing that doesn’t cost the earth and, ideally, we need to now be thinking energy, waste and water neutral. So, a place to call home. It’s that place where you return each day, you might live with family or friends, a place where you belong. That means when you design, you put people first. Good design, as we would all attest as architects, significantly improves the function and enjoyment of a place.

So why Nightingale? I had avoided working on multi-residential projects because, to be frank, I didn’t trust working with developers. In Australia, speculative private development has been the predominant delivery model for multi-residential housing. Owners and investors buy apartments o the plan, the buyer puts a lot of faith in the developer, some buildings are good, many are bad. In 2014, Jeremy McLeod of Breathe Architecture called me looking for micro investors to develop a site in Brunswick. He talked about Melbourne’s problem with urban sprawl, urban compression and the missing middle. Jeremy’s development was to follow on from The Commons, which had garnered great interest from the public looking for a better housing alternative. Melbourne had so many poorly designed, poorly built apartment buildings. I was keen to contribute in a small way, through investing, to see a change.

These are images of The Commons.1 A group of architects each took A$100,000 out of their mortgages to silently invest in Nightingale: Austin Maynard Architects, Architecture architecture, me, Six Degrees, MRTN Architects, and Wolveridge Architects, amongst some others. But good design is only part of the equation. Nightingale 1 was delivered in 2017.

The challenge is that the decision makers in development set the goal posts, and often—too often—we have seen lately that architects are not at that decision-making table. Most property development, to generalise, has been about profit and not about people. So, if the system was broken, it was time to design a new system.

After this project finished—actually maybe even just before it finished—we decided to embark on our own Nightingale project and obtained a licence from Nightingale Housing to do so. One of the principles that Nightingale set was about this replicable model that could enable a lot of architects, who perhaps hadn’t built multi-residential projects, to do so. There was a key focus on the social, the ecological, the sustainable and the financial model. The first bit, though, was that we had to find investors.

1 For further information and images of The Commons project by Breathe, see https://www.breathe.com.au/ project/the-commons.

2 The names of the architecture and design offices that acted as investors were inserted into the transcript in square brackets according to the presentation slide.

We raised A$2.4 million from 24 investors, each investing A$100,000 into our development, including ourselves. The group of people who invested in our project were architects, designers [Fontic, Studio Bright, Kennedy Nolan, Bird de la Coeur, Doherty Design Studio, Zwei Interiors & Architecture, Fini Sustainability], clients and ethical investors.2 It’s certainly hard work and I don’t like asking for money, but people were legitimately interested and keen to be involved. One of our clients, for whom we did this interior fit out a number of years ago, when I asked him why he had invested all those years ago, he had a belief in the Nightingale principles that he’d heard about. He wanted to support quality, environmentally conscious architecture. He was keen to support the development of a community of owner occupiers and wanted to contribute to housing a ordability for key workers close to employment.

Finding a site: We appointed our development and project manager Fontic, who worked with us on numerous feasibilities. We were underbidders on a number of sites but, eventually, a collection of 12 lots was up for sale and Jeremy assembled a group of seven architects to build seven individual buildings to create Nightingale Village just south of

SYDNEY SCHOOL 7

“it was time to design a

system.”

Clare Cousins

3 For Clare Cousins Architects’ site, see site B in figure 1.

4 See also, http://www.wowowa.com. au/portfolio/nightingale-wow/

5 For further information and images of the projects involved in Nightingale Village, see: https:// clarecousins.com.au/projects/ nightingale-evergreen/; https:// maynardarchitects.com/parklifeby-austin-maynard-architects; https://www.breathe.com.au/project/ skye-house; https://www.hayball. com.au/projects/hayball-crtyrd/; http://www.kennedynolan.com.au/ nightingale-village; https:// architecturearchitecture.com.au/ projects/urban-coup.

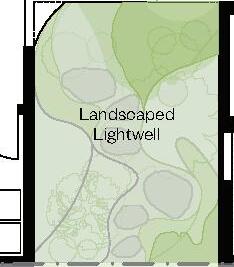

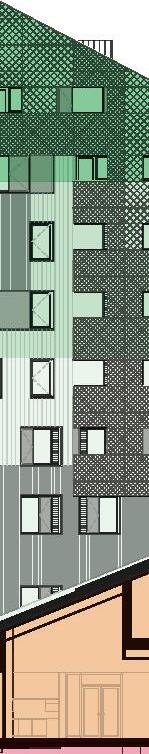

The Commons and Nightingale 1 (fig. 1). This is Duckett Street (fig. 2). All of these factories will become Nightingale Village and a new home for 203 families. This is our site here, abutting the Upfield bike path and the train line.3

This is Duckett Street here—this was the view that you looked through. Five of the buildings nestle about that street. The train line is along through here, and then there were also two other sites along the North and the South. This one up the top, which was designed by WOWOWA, was sadly no longer continued because the City of Moreland, which is the local council, actually ended up acquiring that site to make a new large park. It was very sad to see them go, but great for the Village and the broader community.

This is WOWOWA, the project I mentioned that’s no longer happening.4 This is our project, Nightingale Evergreen (fig. 3–4)—ParkLife by Austin Maynard; Skye House by Breathe Architecture; CRT+YRD by Hayball; and Leftfield by Kennedy Nolan. Then to the South is Urban Coup by Architecture architecture in collaboration with Breathe.5 This is di erent to the other buildings as it’s actually a co-housing project. Residents came together over a decade ago trying to find a way to deliver a building together. Their building includes even more shared communal space, such as a music room, a communal kitchen and a dining room. Here’s the view of their communal space.

Fifteen percent of the buildings across the Village were allocated for purchase by community housing providers, in this case Housing Choices Australia and Women’s Property Initiative.

Some of the architectural strategies that are key across Nightingale projects is the idea of building less and only building what you need, giving more housing for people, carbon neutral housing, the allocation of a ordable housing throughout the developments, removing private ownership of car parking and having a high proportion of bike parking, green transport plan, and a car share hub in this development for both the residents of the Village, but also the broader community. There are no individual laundries, but there’s a shared laundry on the rooftop and clothes hanging space. Ceiling partitions are taken out of apartments to increase ceiling height and expose services. To provide an opportunity to get to know your neighbours, building communities are capped at a maximum of 40 apartments per building.

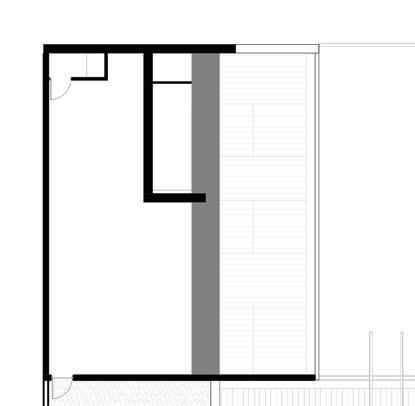

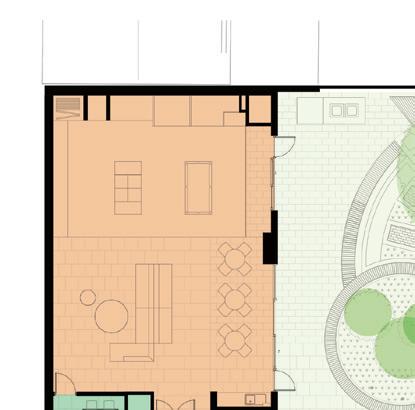

Here is a sketch of our twin-level rooftop (fig. 5–7). It’s on the south side of the building, there’s an undercover dining space and a landscaped area by Eckersley Garden Architecture, a small kind of hydroponic space that we’re still working through with the residents. On the upper level, o from the common laundry, is the clothes drying space and more productive garden area.

Sustainability principles: There’s an energy recovery system within our building, which we felt was important from a thermal comfort but also from an acoustic perspective with regards to the adjacency to the train line. There are ceiling fans throughout. Air conditioning is not included traditionally throughout the buildings. We’ve found, however, the community housing providers typically—because of the age or the health of their tenants—provide air conditioning.

There are low embodied energy materials throughout, reduction and simplification through design. We avoid energy-intensive and high VOC materials and source local materials where possible.

There’s embedded electricity and water networks throughout the buildings, which leads to lower ongoing running costs. The buildings are completely fossil-fuel free, gas is disconnected, renewable energy sources, 24-kilowatt volt to PV panel on our building, and 100% green energy is purchased in bulk for the residents.

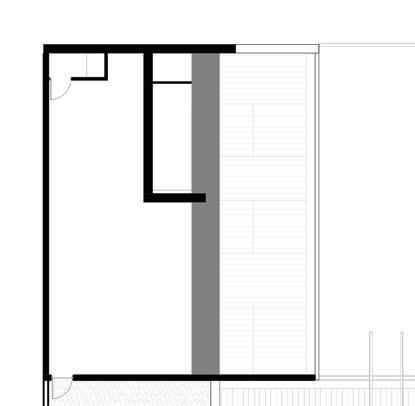

Here we have one called a Teilhaus (fig. 8). It’s a studio apartment of 35 square metres, which was sold for—well, there were two of them actually—one was A$310,000 and one was A$318,000. This was a little apartment that we thought was worth showing. While some States in Australia have actually mandated the minimum sizes of apartments,

Re-thinking Housing Models – Victoria 8

SYDNEY SCHOOL 9 B D E F G C A

Figure 1. Openwork, Nightingale Village, Melbourne, site plan showing site A as a park (acquired by council). Courtesy of Mark Jacques/Openwork.

Figure 2. Photograph taken from trainline along Duckett Street. Clare Cousins Architects, 2017.

Re-thinking Housing Models – Victoria 10

Figure 3. Clare Cousins Architects, Nightingale Evergreen, Melbourne. Visualisation by Thurston Empson, 2019.

SYDNEY SCHOOL 11

Figure 4. Clare Cousins Architects, Nightingale Evergreen, Melbourne. Visualisation by Thurston Empson, 2019.

Figure 5. Visualisation twin-level rooftop, Clare Cousins Architects, Nightingale Evergreen, Melbourne, 2019.

Re-thinking Housing Models – Victoria 12

Figure 6. Plan, twin-level rooftop, lower floor, Clare Cousins Architects, Nightingale Evergreen, Melbourne, 2021.

SYDNEY SCHOOL 13

Figure 7. Plan, twin-level rooftop, upper floor, Clare Cousins Architects, Nightingale Evergreen, Melbourne, 2021.

Figure 8. Plan Teilhaus, Clare Cousins Architects, Nightingale Evergreen, Melbourne, 2021.

6 For the series of images, see video recording, Lacaton & Vassal, Sydney School of Architecture, Design and Planning, Rothwell Chair Symposium, April 28, 2021, Session 2, “Living in the City: Re-thinking Housing Models—Victoria,” video recording, 19:18. Refer to last page for link to recording.

we feel strongly about these entry-level apartments as a form of encouraging people into home ownership and in more a ordable price brackets. There is still a great sense of spaciousness—a bit like that reference image I showed earlier about Flinders Lane apartment—where the bed can have a kind of curtain space. It’s built up on a platform with storage underneath so that it can be used as a day bed during the day or be screened o (fig. 9). These were very popular and sold quickly.

Our residents: 70% of apartments balloted were allocated to first-time buyers. Rather than the apartments being sold on the open market, they are balloted through Nightingale Housing. It’s a very egalitarian process. We recently asked some of our residents—Andy Fergus, who’s an architect, Zibby and Christopher—why they wanted to buy into a Nightingale apartment, and they said that there was trust in the Nightingale principles and that they wanted to live in quality, environmentally conscious architecture. They wanted to be part of a community of owner occupiers, and they were looking for a forever home close to all amenities. Here’s one of our Village gatherings that we had prior to demolition.

Project opportunities: We capitalised on adjacent amenities of the Upfield bike path and train line with direct access to the bike store (fig. 10). We looked at how we could green between buildings, and not just for the residents, but for the broader community. We worked with talented Mark Jacques of OPENWORK on this. Here we have Duckett Street, which Council agreed—given that it was a dead end—could close. We still needed to maintain vehicular access to this adjacent development, but it’s something that we’re funding the cost of converting to a little parklet. Up here, these kind of adjacent edges to the park, and then down here between the four southern apartment buildings, is this residential mews, seen more clearly here. I suppose I used that because I’ve often been fond of the mews that are commonly seen in London. There’s a visualisation from a while ago, Duckett Street’s potential.6

A Park Close to Home: Our building and AMA’s building now abut a new public park, which has been just recently finished on the northern end of the site. Here we’ve got Nightingale Village, here’s the park, this is our building under sca old, and the park as it’s been finished, and the adjacency of the train line.

Commercial precinct: This is Home.one, a not-for-profit that operates out of a 12 square metre tenancy at the bottom of Nightingale 1, where 100% of profits are reinvested into hospitality training for young people experiencing homelessness. The Village will have ten ground floor commercial tenancies, so we look forward to having these occupied by values-aligned tenants that will benefit the Village, but also the broader community.

Development Structure: Six buildings meant that there were 12 directors. So, it made sense to form another company entity in which each building had a stake, which then allowed us to seek project finance collectively. The thing to remember is that many of us established our development companies when we were looking for a Nightingale site—before the Village was, I suppose, found. So, we all had completely individual development companies.

Seeking finance is a whole new process, which is not the role of an architect. We gained a new level of appreciation of the work and the risk of a developer. Rather than appoint six builders for six buildings, it made sense to consider one builder for the whole project. In order to ensure the tender documentation package was cohesive and felt like a single project, we decided it should be executed by one architect. Each architect developed their building to 50% design development and handed it over to Hayball to execute with the design architect’s oversight. During construction, the design architect doesn’t have the role of architect—which challenges a number of us—but rather of client. So, switching roles has been a challenge throughout the project. Some decisions require you to take your architect’s hat o to be the developer, the director responsible for delivering a great building to residents and a return to investors.

Re-thinking Housing Models – Victoria 14

SYDNEY SCHOOL 15

Figure 9. Clare Cousins Architects, Flinders Lane Apartment, Melbourne.

Photograph by Lisbeth Grosmann, 2013.

Re-thinking Housing Models – Victoria 16

Figure 10. Plan ground floor, Clare Cousins Architects, Nightingale Evergreen, Melbourne, 2021.

7 For construction photos, see from min 21.30. Lacaton & Vassal, Sydney School of Architecture, Design and Planning, Rothwell Chair Symposium, April 28, 2021, Session 2, “Living in the City: Re-thinking Housing Models—Victoria,” video recording. Refer to last page for link to recording.

Quino Holland

393 Macaulay Road, Kensington

Here we have some progress photos of the Village as it’s been tracking. This is ours with AMA’s under the sca olding. Some of Kennedy Nolan’s precast panels with the oxides. Some of our balustrades going up. Our entry colonnade.7

Looking to the future: The Nightingale model has evolved. The micro investing, seed funding is no longer required, as finance is sourced from larger institutions who have seen what can be delivered and want a piece of the action. The model wouldn’t have worked without the original grassroots investors, so thank you to them. The Nightingale Housing team has expanded to include in-house development managers and finance expertise to scale up and improve e ciencies. There are new projects in the pipeline in regional Victoria and now Adelaide and Sydney.

We are now working with community housing providers on various housing typologies. We’re also designing a new specialist disability apartment for people with high physical support needs, located in a middle suburb of Melbourne in a residential street. The developer acquired a double site with an existing permit for apartments with an obligatory wedding cake planning envelope, which we architects typically hate. We’ve designed a new building, sitting within this envelope constraint, to accommodate 15 one- and two-bedroom Specialist Disability Accommodation (SDA) apartments with a key focus on well-being and independence for participants.

It’s an exciting time to consider alternative housing models, whether it be Nightingale or the Assemble model, Build to Rent, Baugruppen, or others. We need housing models that deliver high quality, sustainable homes designed for long-term needs of people who live there and their community. We asked what our residents are looking forward to when they move into the Nightingale Village, and they said the social and emotional connection, becoming a community. They’ve got a WhatsApp group, where they’re already planning future amenities and dinners with neighbours, child- and dog-minding, and they’re excited for their new home.

Thank you.

RS

Thanks so much, Clare. That was an extraordinary amount of material you covered in 20 minutes and I’m sure we’ll come back to some questions. What we might do though is, straight to Quino. Are you ready to go, Quino?

QH

Thanks very much, Rod. Hello everybody, I wish I could be there in person. Should I share my screen?

RS

Sorry, Quino, I forgot to say before—anyone who wants to ask a question, please put it into the chat. I forgot to say that at the very beginning. I apologise, Quino.

QH

No problem. Well, thanks very much everybody. I’m delighted to be presenting to you today. Thank you very much for the introduction, Rod, and thanks, Clare, for your talk. Before we get started, we’d like to acknowledge that the project that I’m going to be presenting today lies on the Traditional lands of the Boon Wurrung and Wurundjeri people of the Kulin Nation and we acknowledge that sovereignty was never ceded and pay our respects to Elders past, present and emerging and extend this respect to other Indigenous Australians who might be present.

SYDNEY SCHOOL 17

“Some decisions require you to take your architect’s hat off to be the developer”

Clare Cousins

8 See also https://assemblepapers. com.au

We founded Fieldwork a little under eight years ago. We started by focusing on multiresidential. I’m very interested in housing generally and we’ve been able to work with some terrific developers in Melbourne to deliver some projects we’re very proud of. We’ve also been working on o ce buildings. There is a number of o ce buildings under construction and completed. Since last year, we also had our first cultural project completed, which is the Collingwood Yards project in Collingwood. That’s the first of our cultural projects, which is really exciting for us. Now, we’re also working on aged care, we’re doing a couple of schools, and also a social housing project—diversifying there.

For a little bit of historical context: with my business partner Giuseppe Demaio and Ben Keck, we founded Assemble many years ago. The original intention for Assemble was to try and put design and the needs of the residents front and centre. I’d come back from Denmark really inspired by the co-housing models I’d seen over there and wanted to try and do something like that here in Victoria. The resulting building is in Roseneath Street, Clifton Hill. I actually live in the building, so it’s a bit of a living, breathing laboratory for me. I’ve learned an enormous amount living in a building that I’ve designed along with a large community. It’s 49 apartments and 18 town houses.

Up until early last year, I was design director at Assemble. Since then, I’ve stepped away from Assemble day to day. It’s now got a very dynamic new team and an expanding portfolio of properties. Assemble’s mission is to provide very well-designed sustainable houses and to improve access to housing for people. There’s a 25% share in Assemble, which was purchased by Australian Superannuation—so they’ve got a very big connection to superannuation now. Also, they’ve recently announced a partnership with Housing Choices in order to deliver within Assemble projects a component of social and more a ordable housing as well, so that’s very exciting. Now Assemble has a large pipeline of several thousand apartments.

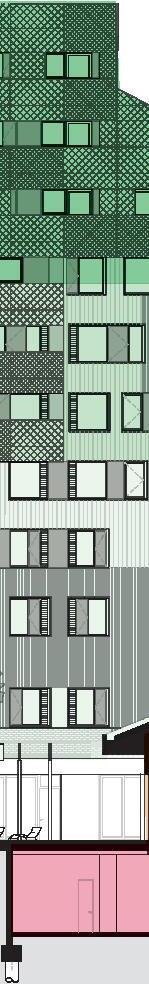

The project I’m going to talk to you about today is Macaulay Road in Kensington. It is the first project we have designed for Assemble to be delivered under the Assemble Futures model, which is an alternative pathway to home ownership.

The way it works is that residents sign up to a five-year lease with the option to buy at the end of that five-year period at a pre-agreed price. What this does is a couple of things. First of all, it gives people a very safe, a very stable rental for five years, and then a fixed goal to work towards at the end of the five years—a fixed price to work towards. Assemble supports the journey through financial coaching and bulk-buying initiatives to assist people to be able to purchase the home at the end of the five years. What I love about the model is that it creates a fantastic alignment—and Clare touched on it before, there’s a lot of mistrust of developers out there. It’s worth noting Assemble is doing pure build-to-rent as well but, through the Assemble Futures model, there’s a really fantastic alignment between the interests of the residents and the developer. As an architect, I love sitting between that, because the residents are able to have this five-year “try-out-the-building” before they decide to buy it. It means we’ve got to design a building which ages very well and is actually a beautiful building to live in.

As I talk through the project, I’m going to talk about the design characteristics that we’ve imbued the building with that take it beyond the conventional apartment building.

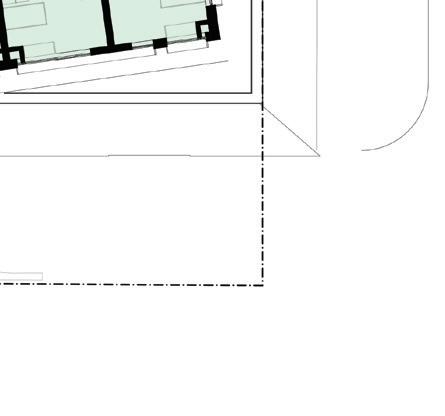

For the first project, we did a lot of surveying and research and workshops with prospective residents, and that research has fed into what the project is (fig. 11). I should also note, we founded Assemble Papers, a publication that continues to thrive to this day.8 When our friend on the right-hand side there picked up a copy, it was a career highlight for me.9 It was at a workshop we did together.

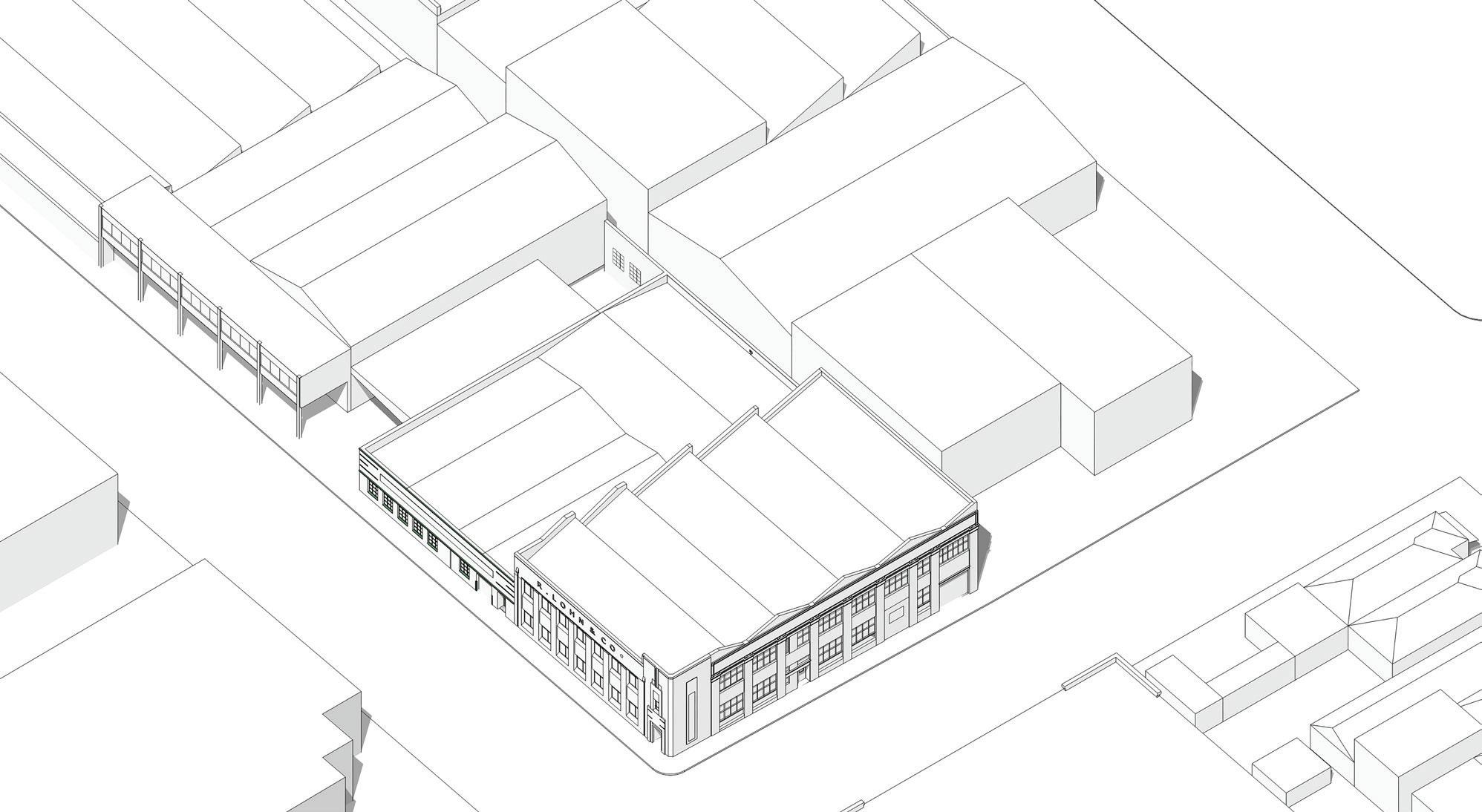

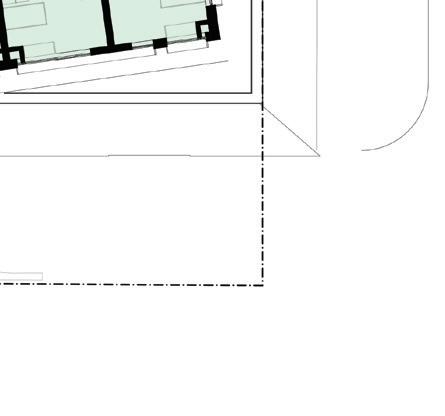

The project is located in Kensington, which was a working-class suburb northwest of Melbourne. It’s gone through a lot of gentrification now. It sits to the north of a large industrial and railway complex and adjacent to the freeway (fig. 12). Our site is in the middle. It sits on the border between what used to be light industrial and is rapidly transforming into

Re-thinking Housing Models – Victoria 18

9 Slide shows a photograph of Rem Koolhaas reading an issue of Assemble Papers

SYDNEY SCHOOL 19

Figure 11. Workshop with prospective residents, on-site at Roseneath Street, 2017. Photograph by Tom Ross.

Re-thinking Housing Models – Victoria 20

Figure 13. Fieldwork, aerial view indicating the site on Macaulay Road in Kensington, Melbourne.

Figure 14. Harry A. Norris, former R Lohn & Co. Factory, Macaulay Road, Kensington, 1928. Photograph by Tom Ross.

Figure 12. Fieldwork, aerial view indicating the site on Macaulay Road in Kensington, Melbourne.

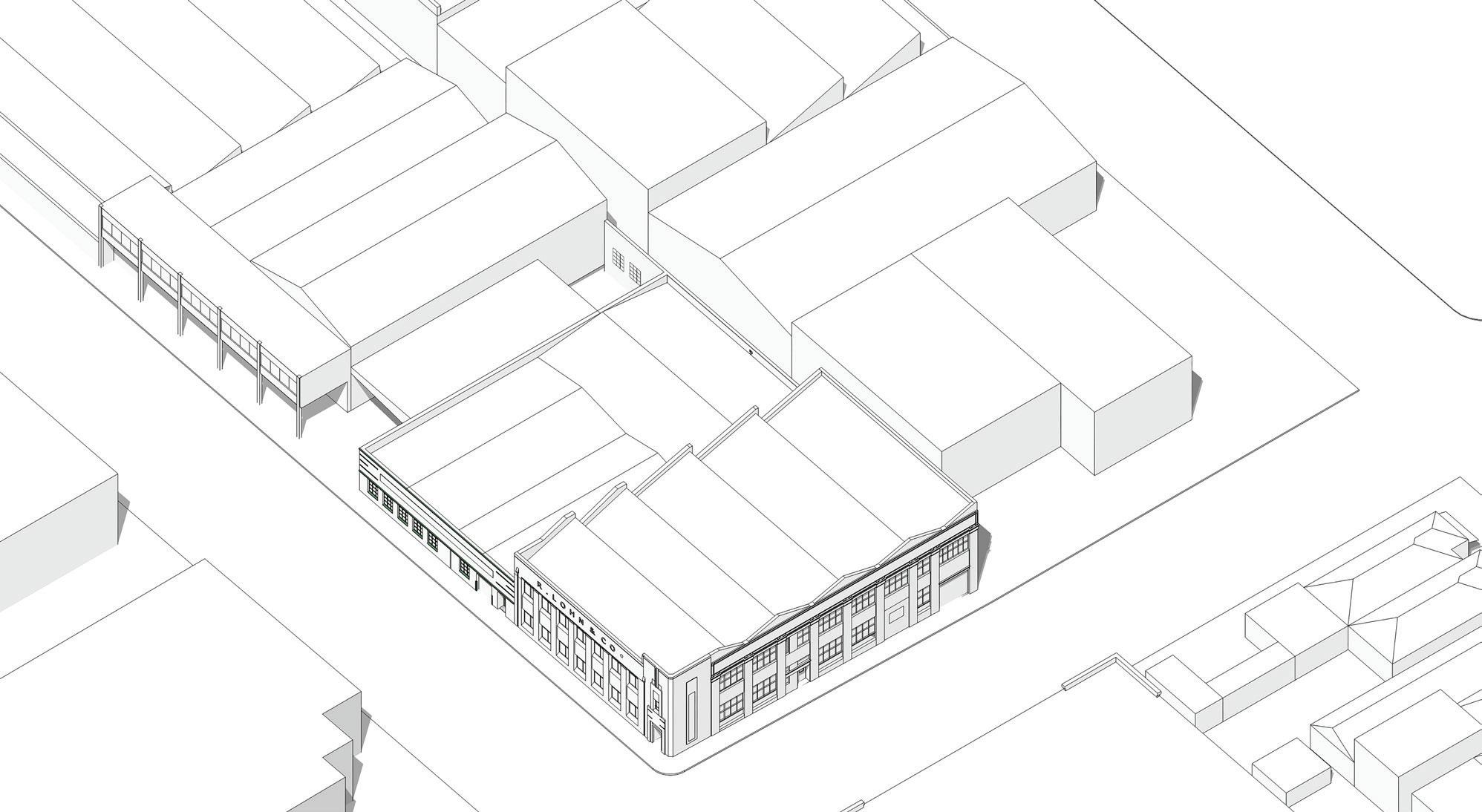

residential and commercial use. You can see, at the bottom left-hand side of the screen, remnant pockets of Victorian workers’ cottages (fig. 13). The building itself on the site was designed by Harry Norris, who’s quite a well-known art deco era architect in Melbourne and has done some beautiful buildings (fig. 14). We were very keen to preserve as much of the building as we possibly could, both from a sustainability and a historical and urban fabric point of view. The building was used—up until we started the project—as a CD-burning factory and, fascinatingly enough, a lot of CDs are still burnt in Australia for commercial use.

An ongoing interest of ours and Fieldwork has been these six-pack walk-up apartments that were built between the Second World War and the 1980s. They’re scattered throughout the suburbs of Melbourne, and one of the characteristics I really love about them is the external circulation space. A lovely feature is that very often the residents actually start to inhabit those spaces. You see little moments of pot plants and bicycles and even people sitting and enjoying that. That’s a real inspiration for the circulation spaces of this project.

I also lived for ten years in a Victorian terrace house. This is not my house, but this is a classic example, where that front verandah creates this really lovely threshold between private and public. Each of these houses has got a private backyard, but this little interface for me is quite fascinating and I really wanted to try and introduce that notion into this particular project. Assemble is not just about squeezing as many people as possible into a building. It’s actually going: Well, how can we make the connective tissue of the building— the thing that holds all the apartments together—into something richer, into something that actually is conducive to getting to know your neighbours, a space you can inhabit. My observation of this kind of threshold space is that it’s actually a lovely space to meet your neighbours.

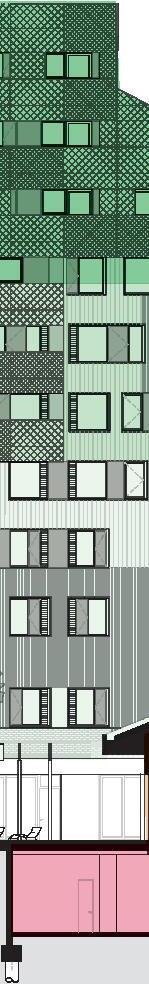

This is an axonometric view of the existing building (fig. 15). A typical approach would likely be to put a corridor in the middle and then apartments around the edge. Instead, we split the building open, which allowed us to have external circulation spaces. This fundamentally changes the way the building works. It means that most of the apartments have got north and south light. It means it works fantastically from a crossflow ventilation point of view. But it also means, rather than walking along a darkened corridor to your apartment, you’re actually in this lovely external space.

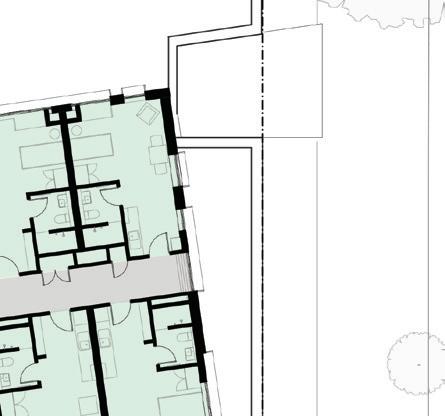

As we go through the project, I’ll talk about all the communal spaces because that’s a really big focus with Assemble. Here is an axonometric view of the building (fig. 16) and the front elevation. What we tried to do, is make it a very, very simple building. A lot of the principles that Clare talked about are similar to the principles we have taken, in the sense that we’re trying to make this a building that ages gracefully, that we’re not building anything unnecessary, that we’re focusing on the things that are going to make it a nice place to live. There is a big focus on thermal and acoustic insulation, on materials that will age very well and a very strong sustainability agenda. It’s got a very large 35-kilowatt system on the roof; it’s a fossil fuel-free building as well. From the front and side elevation you can see we retained the building on the base and not just retained the façade but made sure it had that sort of depth of rooms behind as well. The materiality is very simple, it’s vertical ribbed white concrete, so something that will age well. At the top of the building, you can see the cantilevered bridge out there as well, which is adjacent to the communal room.

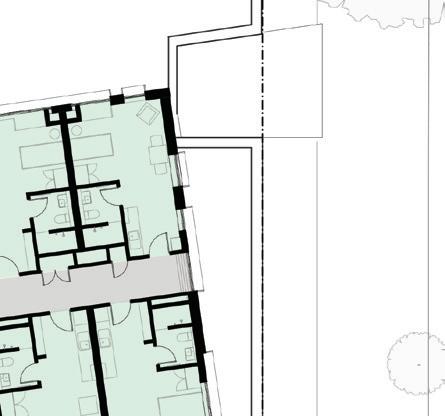

I’ll take you through the plan starting at the ground floor (fig. 17). Through all the research we did, and also talking a lot to the prospective residents, we made the decision to include car parking in the project, but it’s done in a bit of an unusual way because we do have a lot of prospective residents who have work vehicles, for example, or families, and there’s also a very broad demographic that are moving into these buildings, so there are people with mobility needs. So, the decision was made to provide car parking. But it’s done in an unusual way in the sense that the car parks are actually owned for the first five years by Assemble and rented out to individual tenants—those who want them during the

SYDNEY SCHOOL 21

“how can we make the connective tissue of the building—the thing that holds all the apartments together— into something richer, into something that actually is conducive to getting to know your neighbours, a space you can inhabit”

Quino Holland

Re-thinking Housing Models – Victoria 22

Figure 15. Fieldwork, Macaulay Road, Kensington, Melbourne, axonometric drawing of existing building.

SYDNEY SCHOOL 23

Figure 16. Fieldwork, Macaulay Road, Kensington, Melbourne, axonometric drawing.

Re-thinking Housing Models – Victoria 24

Figure 17. Fieldwork, Macaulay Road, Kensington, Melbourne, ground floor plan.

1 5 4 3 2

Legend: 1 Parking, 2 Lobby, 3 Multi-purpose Communal Workshop, 4 Lending Library, 5 Assemble Space.

SYDNEY SCHOOL 25

Figure 18. Fieldwork, Macaulay Road, Kensington, Melbourne, typical floor plan.

Re-thinking Housing Models – Victoria 26

Figure 19. Fieldwork, Macaulay Road, Kensington, Melbourne, visualisation of external circulation space.

Visualisation by Gabriel Saunders.

five years. At the end of the five years, the ownership of the whole car park goes across to the residents collectively. The residents could then get together and decide if they want to continue renting out individual car parks to the owners of the building or, in the future, if car ownership patterns change in some way, that could be repurposed for something else. So that’s trying to allow that sort of flexibility.

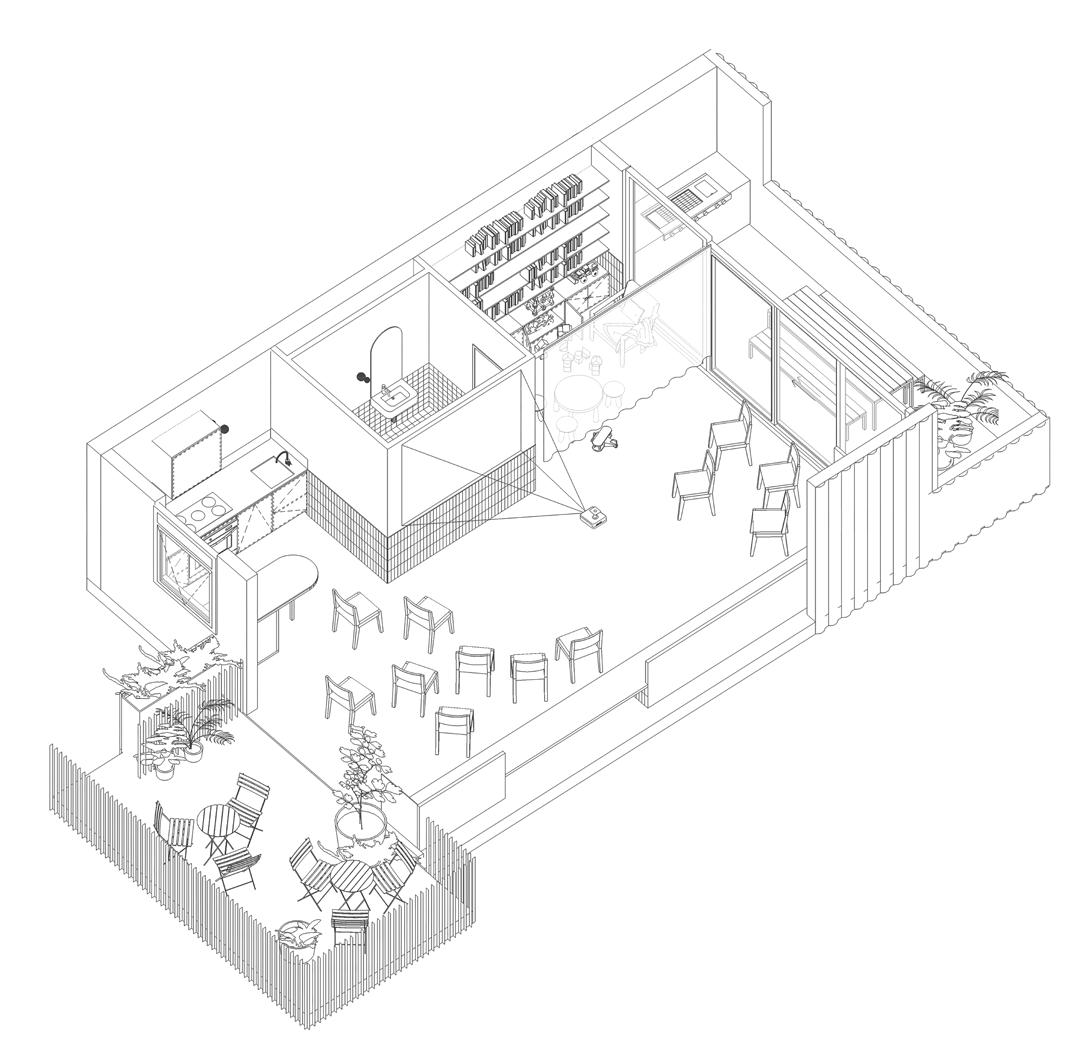

On the ground floor we’ve got a very large, generous lobby entry space. Adjacent to the lobby—and this is one of the first features that I’ll talk about—we have a multi-purpose communal workshop space. We did a lot of analysis of the disadvantages of living in an apartment compared to, say, a freestanding house, and one of the things was a space to tinker around in, like a shed. So, we’ve done a multi-purpose workshop here, which is going to have laundry facilities, a big work bench. I should note that all the apartments have their own little laundry space, but then there’s a shared laundry as well, so some people might decide to turn that laundry into a little study or storage, for example. By putting it next to the lobby, it also becomes a little social moment, so someone might be tinkering away on their bicycle and, as people come in, it’ll be a lovely sort of interface. There’s also a lending library. The lending library is going to be a space—we’ve got one actually at Roseneath Street, Clifton Hill—that has all those sorts of items that you’d like to use very rarely, but it’s not worth buying them—things like a slow cooker, a sous-vide machine, a dehydrator, a pasta maker—all these sorts of things that you sometimes use.

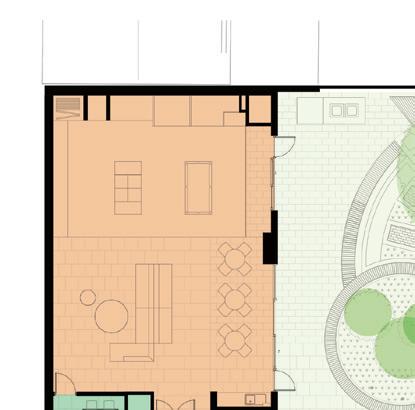

We’re also working with Six Degrees, who are doing an interior design for what’s going to be called the Assemble Space. It’s a ground floor multi-purpose space with a focus on hospitality but which can also be used by the residents in the building as well as an amenity for the broader community. Going up through the building, this is the floor plan where you can start to see the bridges and links across (fig. 18). You can see that each apartment has almost a little front veranda and the living spaces and bedrooms around the bathroom, and then everyone’s got their own private terrace. That little bridge becomes that interface between private and public, which I mentioned previously, like the front veranda of the Victorian terrace house. The lift and stairs—the staircase is an open stair.

I should comment on this curved shape here. We worked very closely with Assemble and the builders to try and make sure that it was incredibly e cient in terms of the construction. The builders suggested they wanted the spot to put their crane through the building. Originally, I thought, "This is going to be a disaster, this terrible big hole in the middle," but then we turned it into this lovely curve, and I think it’s going to be a beautiful feature. That’s where the tower crane is sitting currently.

On this level we’ve also got some further communal amenities—external undercover clothes drying lines, a large herb garden, a kids’ play area, and dog running space. These buildings are designed so that you can have a very complete life, where you can have dogs and kids and all that kind of thing. It’s a very relaxed sort of architecture, and there’s also a dog washing spot there. These are things that we found out through our research—what will actually improve people’s lives in these apartments. It’s not gyms and swimming pools and things like that, it’s actually practical things that will help people have a good life there.

Here you can see it’s a real mix of two-bedroom and three-bedroom apartments. There are some one-bedroom apartments on the lower levels. A sectional view through the building shows that four-and-a-half-metre wide external circulation space. What that has is a series of handrails and then stainless-steel mesh, it’s going to be a quite open space, and there’s quite extensive landscaping through there and a series of planter boxes. This is the northern elevation, so you can see that there are deep eaves towards the north, and each apartment does have light from both ends. Here’s an image of what we hope that space will look like and, in fact, it is starting to look like this (fig. 19). Obviously, the residents haven’t moved in yet, but the construction is due to be finished in a couple of months. We’re really hoping that the internal light of the building spills out onto these spaces and it becomes a much more positive space than a typical circulation diagram. That’s an image on the

SYDNEY SCHOOL 27

right-hand side there of that tower-crane, the curved space that cuts through the middle. It’ll be a lovely void, which brings light right down.

An axonometric view through one of the apartments further explains the typical arrangement of this kind of front veranda, and then the circulation space out here, stepping into the kitchen/dining area, living space, and then the private terrace with planter box, and the two bedrooms—this one has two bathrooms. From a cross-sectional view through it, you can see that on the right-hand side of that totally private space, and on the left-hand side, is the semi-private or semi-communal space, which is the walkway. Rather than having opaque glass—what we didn’t want to do is create privacy that might lead to isolation—we solved the idea of privacy through curtains that can be pulled across. Our inclination is that people will keep these open a lot of the time. Our level one on Roseneath Street, where I’m living, has a very similar arrangement, and during the day most people just have their blinds or curtains open and wave to their friends as they walk past.

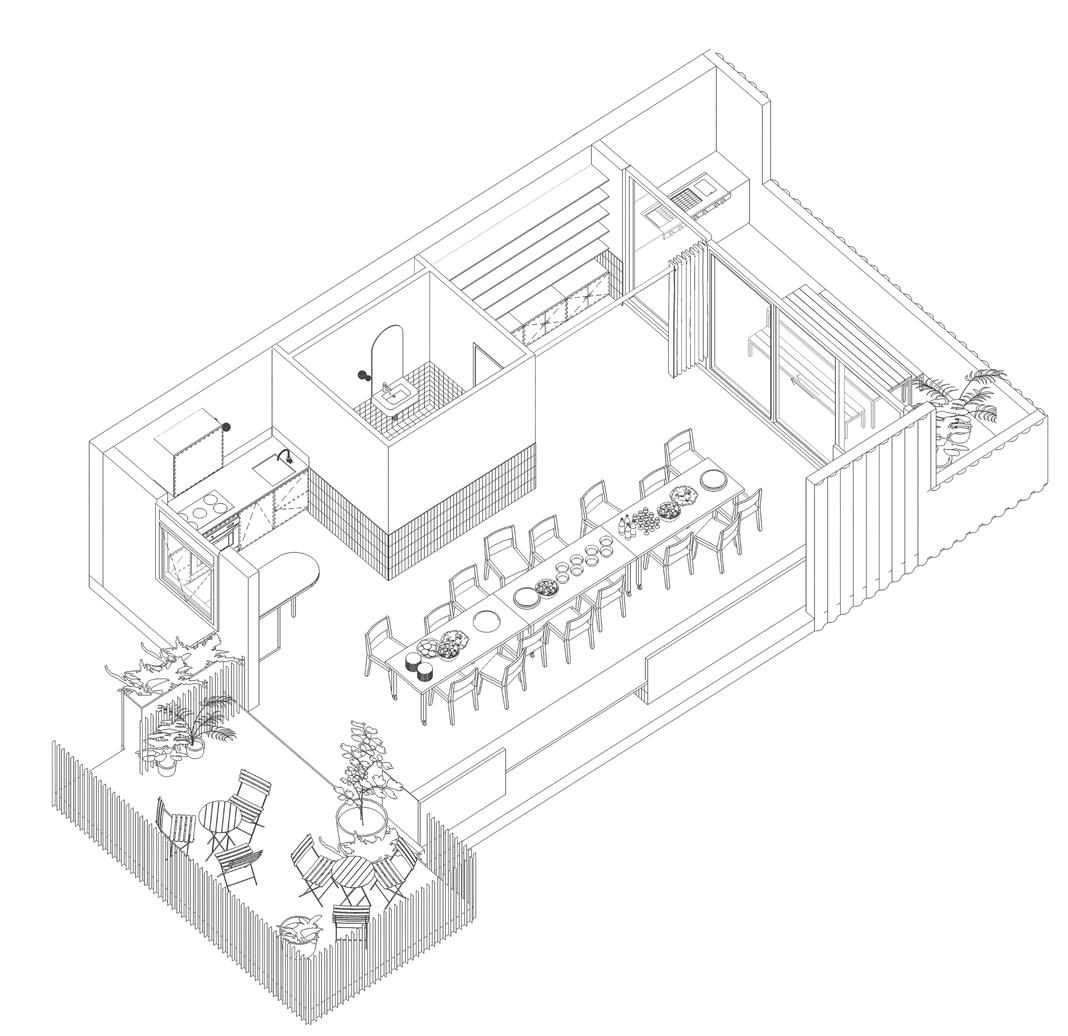

The other important amenity, which is provided in Assemble buildings and is being built into this one, is a multi-purpose communal room. The idea here is, it’s a space that’s very flexible. It’s almost like a shared little scout hall that belongs to everyone, a little school hall that everyone gets to use. It’s a space that any of the residents can book through an online system. We have one at Roseneath Street, and it has been fabulous. It’s a 65 square metre space—I’ve had two of my kids’ birthday parties there—and there’s a lot of things that go on there. There’s yoga classes and Pilates, and a lot of resident-organised things.

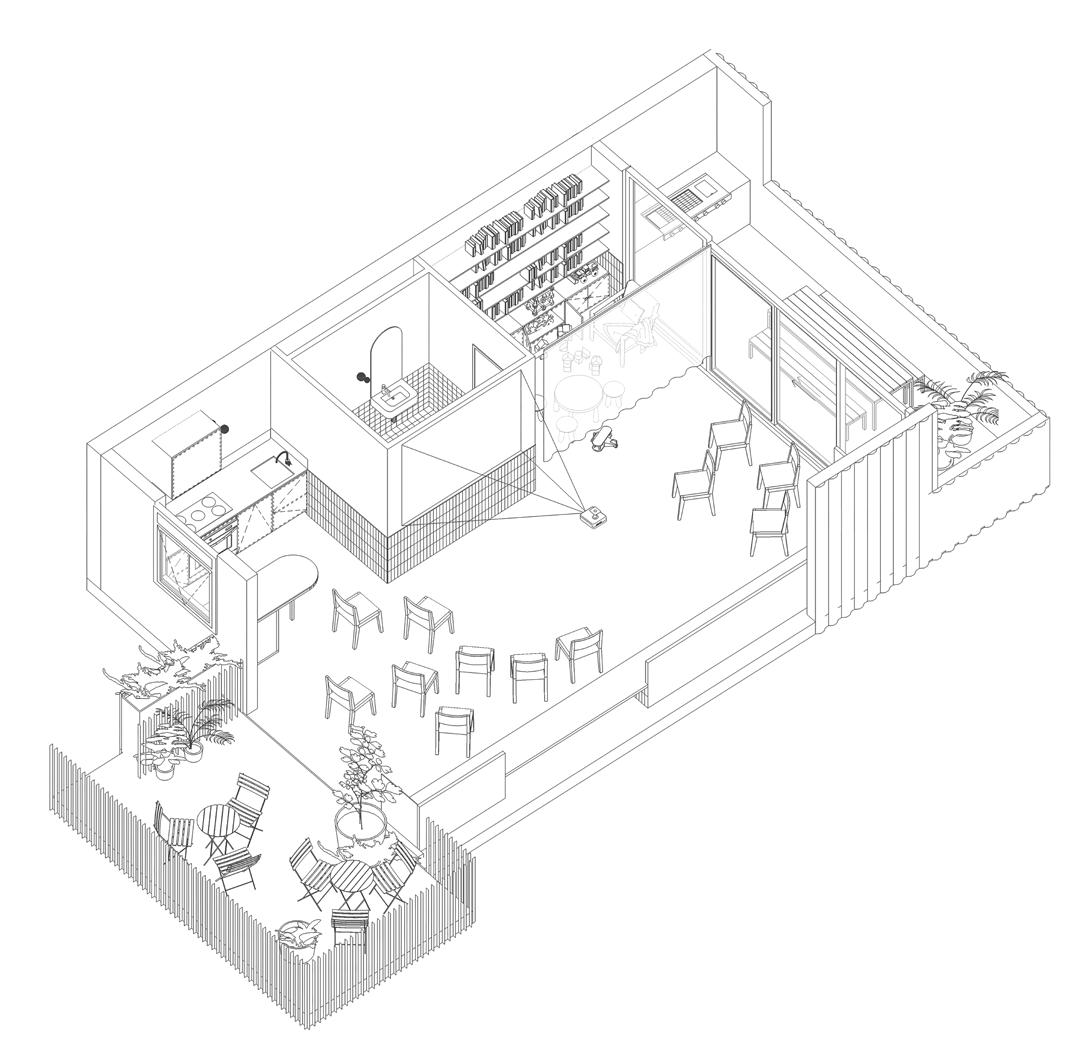

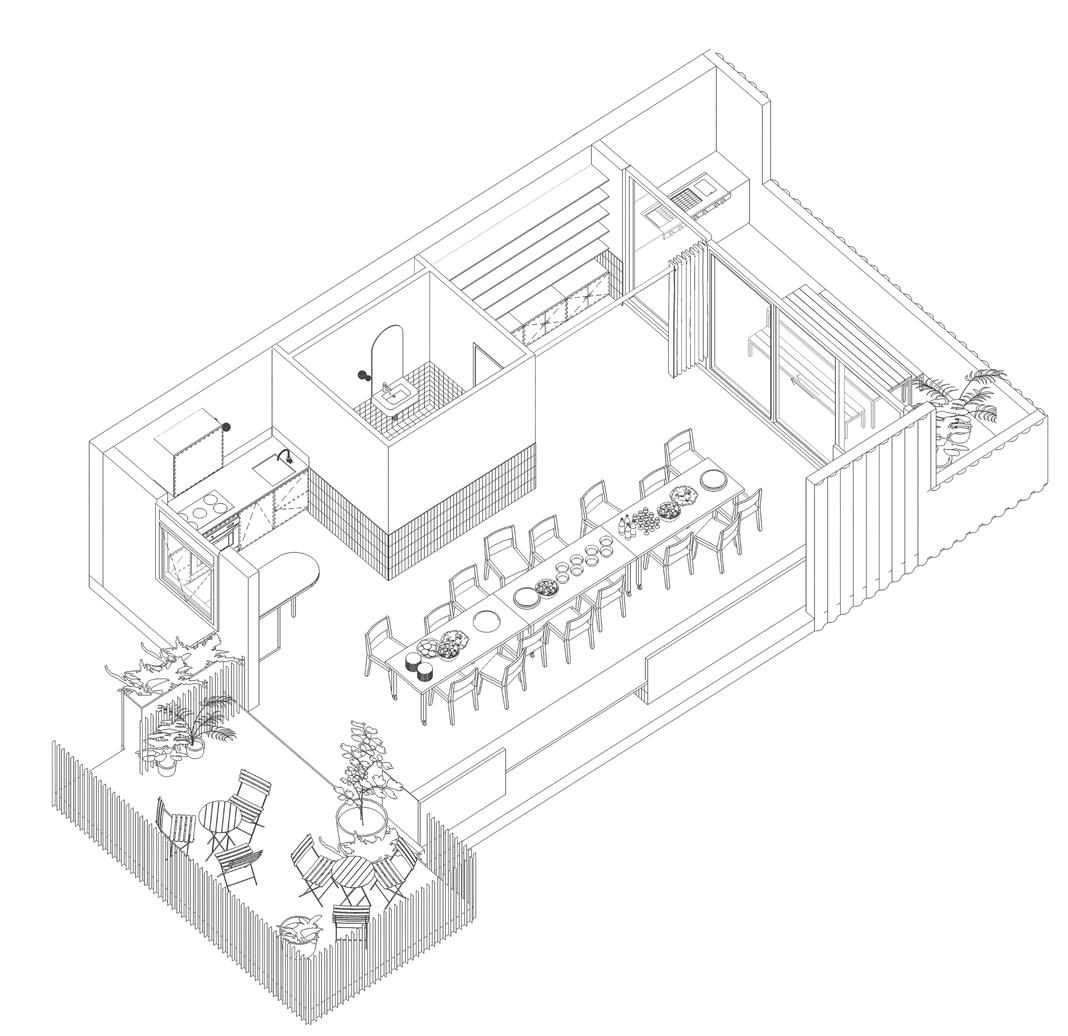

This is on the top floor of this building, so it’s got the very best views and very best amenity. Here is an axonometric study—we try to layer a lot of functionality into this communal space (fig. 20). It’s got a barbecue area, a little kids’ nook with a curtain with a bit of a library space, a bathroom, a kitchen space and a little outdoor terrace, and it can be configured in lots of di erent ways. We also set it up so that it has flooring—which is a lovely marmoleum, a linseed-based flooring—which is very lovely to touch, so that’s good for playing and yoga and so forth. We’ve also got things like a projector in there to create a sense of occasion if they want it to be a bit of a movie club. A lot of people at Roseneath Street do get together and watch movies. That’s an image of the space.

You can imagine what this does—along with the multi-purpose workshop, the lending library, the circulation spaces, the communal amenities on level one, the dogs’ and kids’ play area, the washing lines, the way we configure the building, and this amenity here—we really hope it’s going to foster a positive community. It’s not about everyone becoming best friends, it’s about creating an armature that will encourage neighbourliness, that will encourage it as a positive place to live. This has really been built on the learnings we’ve had from Roseneath Street, which has certainly got a lot of these components in it.

Not a terrific photograph, but just a quick snap showing you where the construction is at. It is very close, the structure is topped out, and fit-outs are happening at the moment. I’ll say thank you very much. Thanks for your time.

RS

Thanks so much, Quino, I think it’s fair to say that the whole Symposium can be summarised as how do we live well in the city, and that was said last night, of course. I think the particular attention that you’ve given to the social interactions and the potential for neighbourliness in high-density development resonates with a couple of terms that came up last night, which was “mixité,” what we would call mixed-use or a mix of di erent functions, which really can be possible in so many places, and we saw that in your work too, Clare. The other term was précision, which was, I think, the precision of your very close observations of the very intricate way that spaces might be utilised, such as the front veranda. “Generosity” also came up last night—in circulation, but also in those provisions of things other than the housing, to complement it. I think it’s so evident in what you’ve just shown. But without more from me now, over to Rob.

Re-thinking Housing Models – Victoria 28

SYDNEY SCHOOL 29

Figure 20. Fieldwork, Macaulay Road, Kensington, Melbourne, series of axonometric drawings of communal space.

Rob McGauran

Ozanam House: Accommodation and Homelessness Resource Centre

This is my presentation. Excellent. Welcome everybody. I’d like to start by acknowledging and paying respect to the Traditional Owners, past, present and future of the land on which we meet today in Sydney—I’m very pleased to be up here—the Gadigal people of the Eora Nation. The project I’ll be talking to you about is on Wurundjeri land in Melbourne and I also pay respect to their Traditional Owners, past, present and future.

I’m not going to show you lots of our projects today—only one. If you want to look at our projects, please refer to the website.10 I thought it’d be worth talking a little bit about how we work, because we’re a little bit di erent in that respect. We are multi-disciplinary, like many firms, but we also seek to be political in how we operate, and we also seek to operate as a research-led design group. We’ve had ongoing, very positive relationships with universities in the research space for at least the last 25 years, as well as teaching programs within the universities.

The lens that we want to undertake our work through is one that’s predicated on why we exist, and that’s to make positive impact through what we do. That’s supported in the practice over the time we’ve been in practice, since 1985—a culture that is curious, deeply committed to making impact and engaged, values-driven, design-led, collaborative and interdisciplinary. Importantly, we like to think when we look at each of our completed works that they are of the place. Is it going to work? Yes.

Over time and based on the interests of leaders within the practice and where their skills lie and where their passions lie, we’ve identified a series of impact areas around which we seek to punch above our weight, and to influence, and to subvert, if you like, where we see market failure. We like to influence through that the shape of our cities and the institutions that serve them; the priorities for government action; the relationships between communities, philanthropy, governments and institutions to tackle wicked problems; the role that design and design thinking combined with clear purpose can play; and continual review informed through engagement with our research partners on the wicked problems of the time that need to be addressed.

Those areas of focus are particularly, but not exclusively, based on city-based issues. They are always concerning wicked problems that we’re needing to address today, where the unique strengths and capabilities of the places and people and clients, which we’re serving can, we think, lead to positive transformation. Pre-pandemic Melbourne and the Western world were facing a housing problem. Now, we’re facing a housing crisis.

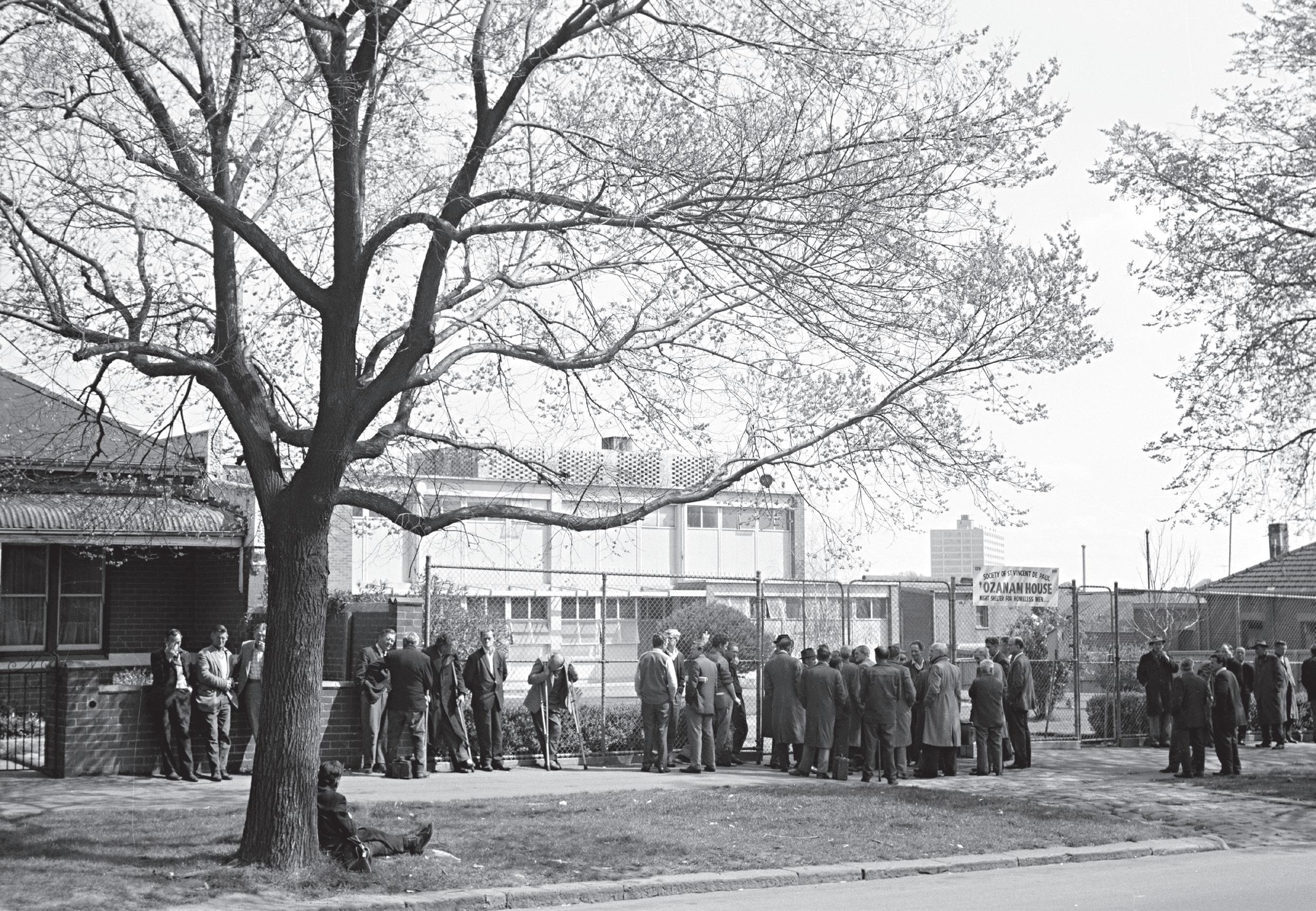

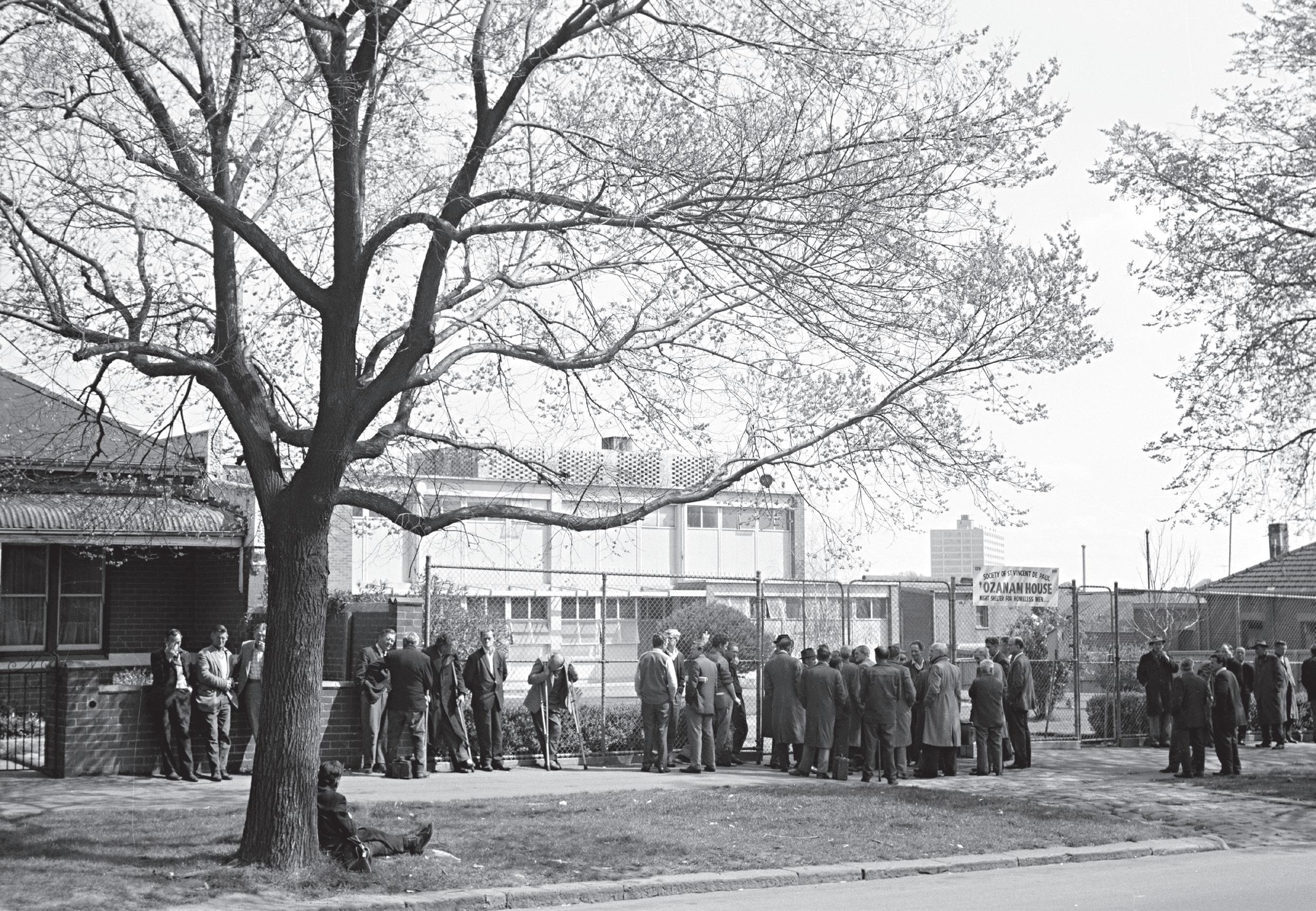

Ozanam House, which I’m speaking to you about today, emerged in the 1950s as an organisational focus for the delivery of homelessness services in post-war Melbourne and followed a tradition of great community-based organisations and institutions engaged in this space (fig. 21). They had recognised, however, that the pre-pandemic surge in homelessness and una ordable housing, rough sleepers, couch surfers and so forth flagged—like canaries in the coal mine—larger systemic issues, and we’re now seeing the floodgates starting to open across the Western world and in Melbourne, Sydney, etc. We’ve seen some politicians and others celebrating a housing boom, people celebrating the fact that they own 29 houses at 29 years of age and this sort of thing. But equally, we’re now seeing people escaping family violence, people who can’t meet rent living in regional areas as well as cities, who are necessary for the underlying functioning of our economies, but also important to the fabric of the communities in which they’ve existed for many years. Solutions need to be found.

Part of that opportunity, we felt, came about when we were approached by VincentCare, who—having run Ozanam House since the 1950s—really felt that they needed to do more with less. They needed to ramp up the diversity and extent of services that could be available to people in a day specialist hub, addressing in particular people who are at risk of homelessness or who were experiencing it, but also to provide people a way out of that cycle—that six-week in-and-out of homeless support, back onto the street and around

Re-thinking Housing Models – Victoria 30

RM

10 https://mgsarchitects.com.au

SYDNEY SCHOOL 31

Figure 21. Ozanam House, North Melbourne, Victoria. Photograph by K. J. Halla, 1966–67. Courtesy State Library of Victoria.

The program

Re-thinking Housing Models – Victoria 32

Figure 22. Ozanam House entry.

Photograph by MGS Architects, 2018.

Day services and administration Resident accomodation

Figure 23. MGS Architects, Ozanam House, Melbourne, program.

amenities: laundry gymnasium IT support support services: fnancial legal housing long stay independent living activities: restaurant/cafe workshops events lounge social health care: dental medical counselling podiatry physio Resident services acute/short stay community hub, lounge and social spaces health services medium stay library gymnasium kitchen IT lab events training 13

11 Slide: “Project brief. VincentCare Victoria developed the new Ozanam House Homeless Resource Centre at their existing site at 179–191 Flemington Road. Services: Homeless drop in program; Homeless health services; Case management and counselling; Participation program; Residential accommodation.”

12 Slide: “Accommodation proposition. Increases in the number and range of accommodation will enable VincentCare to work with their clients over a longer period of time to achieve sustainable outcomes, including an exit from homelessness. Number of beds: 60 short stay accommodation, 48 medium stay accommodation, 26 long stay accommodation = 134 beds in total.”

13 Slide: “Design response. The new Ozanam House Homeless Resource Centre combines the specific opportunities within VincentCare’s unique program with the existing site conditions. The architectural design response: Site arrangement; Built form, Public interface and service offering; Residential accommodation variant; Design quality and materiality; Salutogenic design.”

it goes again—which was being perpetuated more and more, as there was an absence of a pathway out of that. This was the idea of having both the services in an integrated and client-focused way to make real transformational change, but to back that up with a pathway to home.11

The site that they’d occupied since the mid-20th century is on one of the great gateways into Melbourne, Flemington Road, opposite The Royal Children’s Hospital. In the background there is the old nursing quarters of The Royal Children’s, and Ozanam House, as it was, is this site in the foreground here—single story behind the walls (fig. 22). The service provision within the facility, whilst terrific in its plan and what they sought to provide, was undermined by a physical environment described by the residents and sta that we interviewed as unsafe, scary, institutional, noisy, inflexible and unsuitable. It was where they had a few days’ respite, but then were again back on the street.

The challenge for the accommodation proposition that we sought to put in place was really to combine this holistic approach to service with what a pathway to home meant for these people. We worked with VincentCare on the proposition that this pathway would combine short-stay accommodation—which was very typical in homelessness facilities— with medium-term accommodation, typically up to 18 weeks to 26 weeks, and with, for some, long-term accommodation.12 During this time, people were being helped to be well, to be confident, to have the soft skills and hard skills to succeed. It was up to us to provide the physical environment that really conveyed those values and the science underpinning what we did to support that pathway to well-being.

The model that I’m talking about here was very extensive (fig. 23). The day centre on the left provided very comprehensive services in one spot, so that what might have typically taken VincentCare two to three weeks to get wrap-around services for a client, could now be delivered in a day—so, really profound changes to a client focus and as a result, to outcomes. Resident accommodation, as I’ve said, is much more diversified, and I’ll take you through that. Residents’ services that were available to those residents living on site included everything from training on-site, certificate training in courses that would help them get employment after leaving the facility, confidence and engagement with the community, to fitness and wellbeing—because many of them had physical issues as well as health issues, where activity could assist—as well as a range of events, IT so that they could connect again with family, community etc., places to charge their mobiles, cook a meal, wash their clothes, have a shower, along with library facilities and social spaces.

The project really amalgamated a series of diverse and dispersed sites into one. VincentCare sold those other sites as part of its equity into this development. The not-forprofit philanthropic group that I’m now part of was the founding investor in developing the business case for the proposal. Their initial confidence to invest A$750,000 generated a A$46,000,000 investment in the site that’s delivering housing for 154 residents and meals to 500 people outside the facility each day, as well as 250 people per day who access the facility on a day basis.

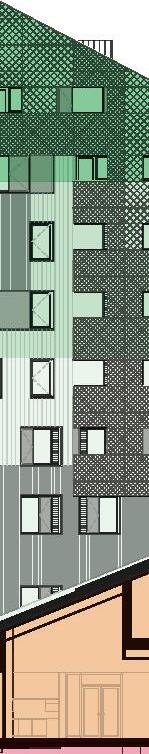

It’s a remarkable location, opposite the Children’s Hospital, on one of the great gateways into Melbourne, Flemington Road, after you come through the ‘zipper’ and into that boulevard. It’s the arrival point to the iconic Parkville knowledge and health precinct. We felt its location also had a civic role in talking to the values of Melbourne in how we express the building. The idea for the project at that broad architectural level sought to continue the exploration in our work—if you go online and look at it—of urban renewal and social inclusion. In particular, how do you develop high density communities that connect to place, but also speak to both collective and individual identity, the importance of city scale as well as street experience.

The design proposition aimed to propagate this idea of the distinctive program, whilst responding to very, very specific client physical, social and psychological needs.13 We wanted to leverage the unique attributes of this remarkable location opposite Royal Park.

SYDNEY SCHOOL 33

14 Slide: “The re-design and redevelopment of Ozanam House was undertaken with the objective to increase and improve appropriate short-term, medium-term and longterm housing options to people experiencing homelessness. The built environment was designed with psychologically informed principles to create a non-institutional environment.”

15 Slide: “Salutogenic and biophilic design methods promote wellness and active health supporting the service programs run from within Ozanam House. Salutogenic Design. Delivering safe spaces that are: comprehensible, manageable, meaningful. Biophilic design: integration of landscape and nature, engagement with the environment to promote wellbeing.”

Those who haven’t experienced the trauma of homelessness, these institutions, rooming houses, and the abuse, health crisis or violence that led to it, might not be aware of how important it is to go beyond what I’ve heard some firms have recently been doing with a ordable housing—vanilla commercial apartments—to thinking more carefully about what sort of environments are needed to help people heal and reconnect, and how we need to organise space to make that journey easier, safer, calmer, and more domestic as an experience.14 Part of the interesting work that we’ve learned through our engagement with the universities over time has been the value of salutogenic and biophilic design, and how we interpret that in our work.15 There is a lot of science now, particularly through the health sphere, about how we can, through architecture, contribute to the well-being of those who engage with that architecture. So, we’ve sought to invest this project with that.

Just quickly through the methodology—and this will be a bit stroboscopic. The existing site went straight to street. We changed that to being exclusively o this beautiful main boulevard opposite The Children’s with the central entrance to the day centre and a southern entrance, or a city side entrance, to the independent living, medium and high-density housing. We created a high level of transparency and programming between the street and the facility, unlike the earlier arrangements, and a real opportunity for social engagement between the two. We used the scale of the adjoining nurses’ premises to think about how we could develop this, if you like, vertical village in this location and how, through pivoting that form and setting it back from the street, we could both talk to the neighbourhood’s 19th and 20th century scale to the north and the amenity needs and the juxtaposition of the building towards Royal Park within that form, and then to scale it down to this human scale that we were seeing as important to the street. The central community areas emulated the location of the backyards in the adjoining areas but also extended vertically through the building. Green roofs, both active green roofs and green roofs to be occupied, connected the building to the adjoining Royal Park. This is how the building formed itself (fig. 24).

Organisationally, if you arrive at the building into the day centre, the concierge there is able to direct somebody arriving and triage them into specialist services, if they need them, and through to social spaces. These include the hole-in-the-wall café, which is manned by residents of the facility undergoing training; the lounge facilities that open into the large courtyard and meeting place; a spiritual space for residents; combined music and practice rooms; and a multi-purpose space—laundries, showers, etc.—if they need that (fig. 25). A dining space opening on to that northern courtyard is part of the day centre experience. For those in medium- and long-term accommodation, their separate entrance takes them into a separate set of lifts where they’ve also got access to gym, library, and those other facilities. After hours, whilst parts of the building close, those residents living above have access to all of these same facilities at ground level, as well as the courtyard.

At first floor level, we have the administration of the facility, a central small social space and higher care, short-term accommodation, where people still get an ensuite bathroom, but there are no separate food preparation areas at those lower levels (fig. 26). As they embrace programs that assist them to develop the skills to move into community, they move into bedsitter-type accommodation, or studio-type accommodation with their own kitchenettes (fig. 27).

Each floor has social spaces opposite the lifts to encourage serendipitous meeting. In the upper levels, independent living units are much more conventional apartment layouts with separate bedrooms, living areas, kitchen (fig. 28). They still have a common social space and their own outside smaller terrace as well. You’ll see in the organising of this, it’s always been about creating small communities or neighbourhoods within the development.

This is how the building was formed—but I’ll take you on a quick run through the building (fig. 29). The practice has always been interested in this crafting of buildings and, I suppose, in engagement with the civic story of cities, and being generous in how buildings engage with social space. The seat has become a very popular place for students waiting

Re-thinking Housing Models – Victoria 34

SYDNEY SCHOOL 35

Figure 24. MGS Architects, Ozanam House, Melbourne. Photograph by Andrew Latreille, 2020.

Ground floor plan: resource centre, day clinic and communal areas

Level 01 plan: admin and short stay accommodation

Re-thinking Housing Models – Victoria 36

access communal staff private clinic MGS ARCHITECTS

communal staff private MGS ARCHITECTS

Figure 26. MGS Architects, Ozanam House, Melbourne, level 1 plan with administration and short stay accommodation, 2019.

Figure 25. MGS Architects, Ozanam House, Melbourne, ground floor plan with resource centre, day clinic and communal areas, 2019.

Level 01 plan: admin and short stay accommodation

Level 01 plan: admin and short stay accommodation communal staff private

2019.

SYDNEY SCHOOL 37

MGS ARCHITECTS

communal staff private

Figure 28. MGS Architects, Ozanam House, Melbourne, level 7 plan with long term accommodation,

Figure 27. MGS Architects, Ozanam House, Melbourne, level 5 plan with medium term accommodation, 2019.

Level 01 plan: admin and short stay accommodation

Re-thinking Housing Models – Victoria 38

ARCHITECTS

MGS

Figure 29. MGS Architects, Ozanam House, Melbourne, section looking west, 2019.

Figure 30. MGS Architects, Ozanam House, Melbourne. Photograph by Trevor Mein, 2020.

Figure 31. MGS Architects, Ozanam House, Melbourne, courtyard.

Photograph by Andrew Latreille, 2020.

communal staff private

ARCHITECTS

MGS

Discussion

for the tram, people waiting for their co ees and having a chat, not just residents of the building (fig. 30). The high level of transparency takes away that, I suppose, mystery, but also a sense of ‘other’ that characterised the previous facility.

Through the rest of this presentation, you’ll see some quotes from the early research that’s been done by the department, our university, etc. on findings, which are incredibly positive in terms of changing peoples’ lives and futures. Here we have the triage desk. Looking the other way towards the hole-in-the-wall café, serving outside to the courtyard in the street, as well as inside to the social spaces. Lounge areas, etc. beyond learning spaces. Courtyard (fig. 31). Looking up to that vertical garden space that, I’m pleased to say, is now lush. Dining spaces, laundry, library areas on the lower levels. Then through the separate entrance and their journey up through the building to go past the sta spaces. You can see this idea of the lounges and those seating spaces next to the lifts at each level to create those serendipitous opportunities.

Moving up through the building, each lounge and each level have their own character and di erence, rewarding people as they go on that journey from short-term to mediumto long-term accommodation and then into communities. Importantly, for some, it will be their long-term accommodation because of their vulnerability. But it’s also to help all residents build their sense of physical and emotional safety and be the best people that they can be and have the best opportunities that they can have.

I wanted to close with this quote, which is something that’s coming into sharper relief by the day. But don’t think this is somebody else’s problem. We can all become homeless through bad luck. This is a quote from one of the gentlemen who was interviewed.

We can all become homeless through bad luck, it could be mental health, it could be substance abuse, it could be financial issues, or physical abuse. If you don’t have something like this, where do you go?

Through my work in the not-for-profit sector, I’ve seen remarkable stories of how this is happening. But now with this explosion of family violence, with this rapid gentrification that we’re seeing, people who wouldn’t have dreamt of being in that position are finding themselves in that position by the day and it’s only going to get worse if we don’t get serious government intervention. Thank you.16

RS

16 VincentCare, Australia’s largest homeless facility, completed July 2019. http://vincentcare.org.au/ our-services/ozanam-house/

Funding: NFP Service provider: 55%;

Government: 40%; Philanthropy: 15%

Thanks very much, Rob. Well, if you’ll bear with me for a moment in reflecting on what we’ve just seen, I’ll lead into some questions. As you know, this Symposium is meant to kick o the Chair in Architectural Design Leadership, and I think you can see why these speakers were invited to present. Because, if we’re well aware of the problem—so clearly put by you, Rob, not only now but in your work—the question then becomes: What is the role of the architect in dealing with these very intractable questions? What are the unique capacities and abilities that architecture has, over project managers, engineers—no disrespect to those professions—but what is it that makes us capable of even thinking about these things? It did strike me that the starting point has to be those values. There’s actually some fundamental values and motivations that exist in practice, as part of the ethos of a practice and then, just from this presentation that strikes me, we can discern a progression, if you like, from recognising the problem, and then that stimulating research, that research leading into understanding the processes, which then become manifest in precedents, in prototypes, in testing, in disruptive projects that start to build trust, that also then start to talk about a di erent relationship with clients. What you then have is the possibility of that design also coming full circle back to thinking, not just about the design of the building, but the design of processes, the design of financial structures, the design of relationships—which I think we’ve seen in all of the projects we’ve just experienced.

SYDNEY SCHOOL 39

“it’s always been about creating small communities or neighbourhoods within the development.”

Rob McGauran

My first question—and I have four— is to do with research. Rob, if you wouldn’t mind reflecting on how your research is fed across into education, and to close the circle completely, how that research now has actually gone back to inform policy. And—we were talking about this briefly before—how the full circle is now actually reconceiving a ordable housing as infrastructure, which has a whole lot of implications in terms of funding and government acceptance and so on, based on research.

RM

Yes, it’s a really interesting question. I was talking to a colleague at the Future Fund not long ago and asking: Do you invest in housing? And they said: Yes, we do, a number of billions. And I said: Really, where? And they said: Well, none in Australia because there’s no investment vehicle in Australia for future funds to invest. We only have investment vehicles for mum and dad investors globally to invest here.

But the value of research both from a practice point of view and the role of the academy in supporting that research, I think, has been profound in changing futures in Victoria in the last, I’d say, seven or eight years in particular. Carolyn Whitzman and Transforming Housing at Melbourne University led a really interesting body of research. There’s a lot of really good work online there that’s been followed up by the hallmark initiative at Melbourne University. Shane Murray and Lee-Anne Khor and others at Monash University have also been doing some great work. Swinburne University of Technology is also doing some good work. But what that has been able to develop over time with industry players—I’ve been lucky to be involved as a practice and then as an individual all the way through that—is to provide compelling evidence of (a) what the problem is, (b) what the best practice models are globally, (c) what the shifts globally have been and that this shift has included recognition that housing is essential infrastructure for our communities. Then, when Infrastructure Australia was formed, the States also put in place, if you like, matching organisations, and Infrastructure Victoria undertook a very extensive formulation of what its priorities should be. We were able to provide that really good research to them, and they agreed that essential infrastructure for our city included a ordable housing. And not just a ordable housing, but a ordable housing of the right type, in the right location, to the right criteria for the right sort of households, at the right price for rent, primarily. In fact, it got to the point of saying, of the top three priorities for infrastructure investment in Victoria, housing was one of the top three along with the Metro—which had already got funded—and the North-East Link—which had already got funded. More recently, the great thing about that is, it changes the return profile that is needed on the housing, because risk is seen to be much lower for infrastructure than it is for speculative property. Patient investment is also encouraged in infrastructure, whether it’s a pipeline, or a freeway or whatever, rather than speculative investment.

When Victoria went into its second lockdown last year and the government started to think about what it should invest in to bring Victoria out of its recession, I was fortunate enough to have been invited to be on the task force with the Director of Housing to help build the business case and identify risks and opportunities. We were able to take what was originally going to be a New South Wales benchmark of A$900 million and change that to A$5.3 billion, as a bid, and we were successful in getting that funding for 12,000 dwellings in Victoria. Further, a not-for-profit that I’m part of—the Lord Mayor’s Charitable Foundation— had supported a project with Brotherhood of St Laurence and supported again through university research a couple of years prior, looking at vulnerable households in the west of Melbourne who were living in poor energy-performing houses and the impact that had on both their living costs and their health. The early research had come back and was, again, a compelling case for investment. Again, because that research was there and ready, we were opportunistically able to secure A$500 million of investment in further expanding that program. So, by having really good and real and current research, with all the questions

Re-thinking Housing Models – Victoria 40

“thinking, not just about the design of the building, but the design of processes, the design of financial structures, the design of relationships”

Rod Simpson

“risk is seen to be much lower for infrastructure than it is for speculative property.”

Rob McGauran

“recognition that housing is essential infrastructure for our communities.”

Rob McGauran

answered, we were able to eliminate the majority of risks for politicians and show the value, but also get the necessary people within the tent supportive of the propositions.

RS

Thanks Rob—I mean that’s a major achievement to get that policy shift and I guess the thing there is to you, Clare, to have those things ready, if you like. If we’ve now finally got the bucket of money and the policy framework based on research, we also then have to have the things that we’re going to build, the precedents, the examples of these alternative ways of doing things. I think the strength in the projects that are going on in Melbourne, is that. If you could talk more about just how you’ve managed to go from a number of individual projects to a neighbourhood and then, of course, expanding into the public domain, the extent to which those precedents have actually been hand in hand with the theory and the analysis, that you actually need both. So, could you just speak about that and how you’re using those precedents to advocate for more of the same stu or more of the even better stu ?

CC

Sure, and well done, Rob, on that 5.3 billion that we’re all getting busy with—it’s very well overdue. Talking about some of the precedents, what’s been really interesting is the shift that I’ve noticed as an architect in the last five years with some of the models that I mentioned before, such as Quino’s Assemble model and Nightingale and so forth. I suppose it was that you can’t always sit around and wait until those big policy shifts happen. Which is the thing that instigated and what put a fire under Jeremy, which then put a fire under a whole lot of other people to make that change.

The challenge was—you know, the whole reason we needed to find seed funding—is because no one would lend a bunch of architects money in the first place, but then making those changes and setting new benchmarks as to what’s acceptable in development. I think Jeremy himself would often say that there was nothing particularly remarkable about The Commons. He referred to it as kind of Scandinavian housing from the 60s. It was actually about this idea of taking it back to being intrinsically simple, well-built, thinking human-centric, all those kinds of basic fundamentals, that I think had been lost in the way that housing had become such a speculative commodity in Australia. It was so much about investor stock. It didn’t think at all about how people lived in these houses. These principles then had to be coupled with the kind of climate emergency that we’re currently finding ourselves in of, you know, eradicating gas, and pushing much higher than a six-star rating, which is what we currently need to comply with.

What I found interesting to observe, as someone that was coming in fairly new to working in the multi-residential sector, was how these initiatives were starting to make the consumer more knowledgeable, more discerning, more demanding, which is fantastic. You know, for so long they’re like: Oh, real estate agents say, this is what you get—well that’s what you get. It was kind of tick a box—how many bathrooms do you get, how many car parks do you get—and that was no longer the case. People were demanding more, which started lifting the benchmark for the private developer. Obviously, there’s good and bad spectrums, there’s certainly lots of good developers in Australia, or in Melbourne. So, you started to see some of those principles that Nightingale had been—I’m not saying they were necessarily the first to do it—but what they were advocating. Secondly, what’s been interesting is seeing how that has filtered through into the social housing procurement. Those principles have been filtering into government procurement for this big second wave or first and second wave a ordable and social housing. Whether that’s a coincidence, who knows? But it’s very interesting how small initiatives, grassroots initiatives, can be quite powerful in making a systemic change across the sector.

SYDNEY SCHOOL 41

“that you can’t always sit around and wait until those big policy shifts happen... housing had become such a speculative commodity in Australia”

Clare Cousins

“how small initiatives, grassroots initiatives, can be quite powerful in making a systemic change.”

Clare Cousins

17 Big Housing Build is a government initiative by the state government of Victoria, Australia. For a press release on the cooperation of Assemble with Housing Choices, see https://www.housingchoices.org.au/ images/Assemble_Housing-ChoicesAustralia_MR_March-2021.pdf.

RS

Yes, thanks. I think that then goes to my third question, which is to you Quino, which is to do with the relationship with the client. Again, just to reflect for a moment, I think it’s fair to say that we think of typologies of building usually in terms of built form, but associated with those typologies—detached houses or duplexes or villa homes or blocks of apartments—of course, they are in fact assemblages of the invisible systems as well. Alongside those are very finely tuned legal, financial and, for that matter, planning controls, and so what you have is, essentially, all of these things coming together into really quite an extraordinary inertia to change and make those new models. Your point about the coincidence—I think you should perhaps claim that it’s no coincidence, that actually the procurement has recognised these benefits. What we’re seeing is the breaking of those connections where you’ve got particular forms of speculative design, where there’s no connection necessarily between the architect and the end occupier. Now we’re seeing these intermediate models, where—and this is to you Quino—where there is a series of ways beyond focus groups, beyond market segmentation or personae, which is the way the market tends to deal with this, but the way that you have managed to engage with the end occupants and to co-create exactly what goes into those buildings, which is exactly the sort of model, I think, that—Clare, you were saying—has started to be picked up by public housing providers. So, Quino, to the question of how you engage with multiple clients to still behave as an architect and actually come up with a design. A challenge.

QH