New Propositions, Q uestioning Costper-Square-Metre and G enerosity

Moderator: Hannes Frykholm

Speakers: Anne Lacaton, Jean-Philippe Vassal, Andreas Hofer, Florian Köhl Closure: Catherine Lassen

Conclusion: Robyn Dowling

DR = Dagmar Reinhardt, HF = Hannes Frykholm, CL = Catherine Lassen, AL = Anne Lacaton, JPV = Jean-Philippe Vassal, AH = Andreas Hofer, FK = Florian Köhl, RD = Robyn Dowling

5 Abstract

6 Introduction

Dagmar Reinhardt, Associate Professor, Sydney School of Architecture, Design and Planning

7 Introduction

Hannes Frykholm, Rothwell Post-doctoral Research Associate 2022–2025, Sydney School of Architecture, Design and Planning

8 Living in the City: New Propositions, Questioning Cost-per-Square-Metre and Generosity

Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal

24 More than Living, Zürich: Sustainable Housing Cooperatives and IBA 27

Andreas Hofer, IBA'27 StadtRegion Stuttgart

35 Spreefeld, Berlin

Florian Koehl, fatkoehl architects/Quest

45 Discussion

48 Closure

Catherine Lassen, Senior Lecturer and Rothwell Chair Coordinator, Sydney School of Architecture, Design and Planning

Robyn Dowling, Professor and Dean, Sydney School of Architecture, Design and Planning 50

48 Conclusion

Bios and Further Reading

How do we want to live in our contemporary cities? What are the conditions that make innovative and a ordable housing possible? These were two of the key questions in this fifth and final session of the Symposium. In many large cities, existing housing stock is increasingly being demolished and replaced with new and una ordable housing development projects financed by large real estate companies. This session turned to alternative models of housing production and innovative modes of their realisation in Europe, which prioritise a ordability and quality of life for inhabitants over financial return.

Lacaton and Vassal presented two of their projects in France: a social housing project in Mulhouse, that was part of a larger scheme called Cité Manifeste; and a project in Saint-Nazaire, which involved the transformation of an existing building within a larger housing complex. The former used inexpensive greenhouse pre-fabrication technologies to create dwellings of almost double the standard size of social housing apartments for the same budget, while the latter entirely transformed and expanded existing units and added new units through a careful process of reinterpreting spaces and adding to the configuration of the existing building in its park-like setting. In this way, the living quality of the apartments was enormously enhanced, and the number of apartments could be doubled without purchasing new land or taking away too much green space.

Andreas Hofer introduced the project Mehr als Wohnen (More than Living) in Zürich, Switzerland—a city in which the majority of inhabitants rent rather than own their homes. Mehr als Wohnen was developed in cooperation with a newly formed housing cooperative and a group of architects on formerly industrial land provided by the city of Zürich. It integrated high quality, a ordable housing, o ce spaces, a communal garden, child-care centre, a hotel and additional public infrastructure. In his role as the artistic director and general manager of the IBA 27 Stadtregion Stuttgart (International Building Exhibition 2027, City and Region of Stuttgart), Andreas also introduced a selection of projects that are currently under development. This exhibition marks the centenary of the famous Weissenhofsiedlung, a part of the Building Exhibition from 1927.

Florian Koehl (Fatkoehl Architects) introduced the concept of the Baugruppen model in Berlin, which enabled future occupants to purchase a site and develop a project in a collaborative process together with the architect(s). The Spreefeld project in Berlin, Germany, is located right on the river Spree on land that used to form the border between East and West Berlin. The ambitious project aimed to provide a ordable housing, o ce and workshop spaces, as well as communal areas. A ordability here was realised through the development of a large variety of individual and communal apartment types of various sizes and configurations, from so-called cluster flats, in which inhabitants share living spaces and kitchens, to more conventional units. Another key concern realised in the project was to provide residents with high quality indoor and outdoor spaces, while still allowing public access to the site and the river Spree.

The discussion highlighted the increasing rarity of those micro-sites and left-over spaces in cities that used to be relatively inexpensive and which provided the basis for alternative housing and realisation models, such as the Baugruppen in Berlin. At the same time, the price of land has risen exponentially in the past 20 years, which poses di culties for alternative models of project realisation. However, discussants were hopeful that models such as those based on the leasing of land, essentially bypassing the cost of purchase, could provide a new basis for fostering innovative and generous housing design.

SYDNEY SCHOOL 5

Abstract

DR

Before we begin, I would like to acknowledge and pay respect to the Traditional Owners of the land on which we meet, the Gadigal people of the Eora Nation. It is upon their ancestral lands that the University of Sydney is built and as we share our knowledge, teaching, learning and research practices within this university, we pay respect to the knowledge embedded forever within the Aboriginal Custodianship of Country.

It’s also a pleasure to come here together in the Chau Chak Wing Museum. We are meeting for the fifth and last session of the Rothwell Chair Symposium 2021, which inaugurates the three-year appointment of Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal. Over the last three days, we have followed discussions with them, invited global guest speakers and Australian contributors on the topic of “Living in the City: Exemplary Social and A ordable Housing Design.” In doing so, the Symposium centres on the way in which architecture can support the enrichment of human life through a lens of generosity and freedom of use towards aiding and, indeed, benefiting the individual socially, ecologically and economically and, in consequence, bringing forward the evolution—and nothing less than the evolution— of a city.

I would like to highlight two aspects that have been extensively discussed in the last few days: space or form as non-conformed potential for individual and society; and acknowledgement of a human condition that allows us, as a society, to be human and to be humane. Social housing, residential space or urban public space are, fundamentally, spaces where the conditions of human nature are defined, where relationships are organised and where the foundation for community and participating in society are laid. This human condition is, arguably, at moments both strange and fragile, as author Jonathan Safran Foer describes so vividly in his recent book We Are the Weather (2019) Foer renders the portrait of humankind as seen through a lens of future generations, hypothesising that, perhaps, future generations will arrange our remains in a museum accompanied by text on what it was like to be human. This is just an excerpt of some of the moments that he lays out for us.

They preferred groups as small as two. They struggled with hydration and gravity. They recorded experiences with writing implements that disappear with use. They brought their hands together to express approval and even non-believers concealed their feet. They had names. Although very few had unique names. They struggled to remain conscious in the dark. They had no armour plates. They passed their death date every year without acknowledging it and pushed their breath into bladders to commemorate being born. Their needs were too great. Doing nothing to save their kind required the participation of everyone. Every single one of them began as a baby and collectively they were relative to the history of this planet extraordinarily young.1

So, the question really is in rethinking the human conditions. How do we want to live? What do we expect from living/space? This is an important question in the context of climate change and a global agreement among 115 countries to take action for change by 2030, formulated as United Nations 17 Sustainable Development Goals. How does architecture participate in the current discourse but, more importantly, develop solutions? In the work of Lacaton & Vassal—in conjunction with an absolutely fantastic call to build simply for a ordability and pleasure—space is generated by introducing an over-plus to pre-existing forms that translates the previous uniformity and functional-driven performance of space towards something other, by encouraging change, storing time and inviting interpretation. A space of potential and ambiguity. This resonates with Dutch architect Herman Hertzberger, also an advocate of human conditions, who argues that a “constructive approach to a situation that is subject to change is a form that starts out from this changefulness as a permanent—that is, essentially a […] given factor: a form which is polyvalent. [Such] form[s]

New Propositions, Questioning Cost-Per-Square-Metre and Generosity 6

Dagmar Reinhardt Introduction

1 Jonathan Safran Foer, We Are the Weather: Saving the Planet Begins at Breakfast (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2019).

can be put to di erent uses without having to undergo change itself."2

This entails conceiving the space for di erent purposes. We have heard a lot about that in di erent ways, on the grounds that di erent activities make di erent specific demands on the space in which they are to take place. Most importantly, it is people who make specific demands, because they wish to interpret one and the same function in their own specific ways. Hence, collective interpretation of individual living patterns can be abandoned in favour of the diversity of space in which individual interpretation and communal living patterns meet. This is made possible by an ability to accommodate, absorb and, indeed, induce every desired function and alteration thereof.

In the work of Lacaton & Vassal we can see such a deep systemic change of considering space as similarly polyvalent, with new spaces that invite the user and occupant to interpret, to adapt and to inhabit—by increasing the competence of form and space through possibilities for associations, interactions and human individual life choices and habitation. This might just enable us to build from where we are now, to develop new propositions and think our ways of living and rituals of daily life together towards the future, in 2030. Our massive thanks go to Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal for leading these discussions and to Garry and Susan Rothwell for a philanthropic gift, generously given: a gift that will keep giving over the next three years. Thank you. It is now my pleasure to hand over to Hannes Frykholm for further moderation.

Thank you for joining us.

Hannes Frykholm

Introduction

2 Herman Hertzberger, Lessons for Students in Architecture (Rotterdam: 010 Publishers, 2001).

HF

Thank you very much. I welcome all of you to the fifth and final session of this Rothwell Chair Symposium of 2021. My name is Hannes Frykholm. I am an architect, PhD and teacher based in Stockholm and also the future Rothwell Post-doctoral Associate. I’m going to be moderating this session, which we called “New Propositions, Questioning Cost-per-SquareMetre and Generosity.” With this title, we wanted to be very pragmatic, to try to identify alternative models of housing production that can challenge existing norms, standards and conventions, while at the same time bringing additional qualities that are often overlooked. We also wanted to highlight the obstacles and the struggle involved in this attempt and the things that do not always go as planned. We think there’s a lot to learn from the issues as well as the problems.

Following what David Harvey calls the new liberal turn of the last decades, we are witnessing a growing commodification of housing, where the home is often seen as an investment rather than a fundamental human right. Driven by speculation and profit concerns, even redevelopment of the existing city, as Rosalind Deutsche reminds us, lead to evictions of those already marginalised. As cost-per-square-metre becomes, perhaps, the only way to evaluate what is built, there’s definitely a need not only to question corporate models of housing production, but also to discuss the qualities of good housing that cannot be measured in economic terms. We can think of this as a kind of generosity of architecture—housing projects that promote pleasure and joy in everyday life and can open up for new ways of living together and living in the city. Generosity, then, is not only to decide, design and build what is economically a ordable, but also to accommodate new and di erent modes of living, providing housing with flexibility and more freedom for its inhabitants. Somehow, it seems that the problem is not that we don’t know ways of doing things better.

We are going to see some beautiful examples of that in this session, projects that are a ordable, but which also o er high quality housing. Of course, we’re very happy to have Anne and Jean-Philippe with us for this session, as I think many of their projects include both this generosity of architecture and, at the same time, a very pragmatic understanding of building implementation in relation to budget sheets, the cost of square metres and so on. We also have Andreas Hofer in the panel to speak about his work on cooperative

SYDNEY SCHOOL 7

Anne Lacaton

Propositions,

housing projects in Zürich, a form of housing development that is—at least as far as I understand—partly protected from speculative investments and finance capital through a certain set of legislation. I’m also very much looking forward to hearing Florian Köhl speak about his work with the Baugemeinschaft movement in Berlin, where small-scale development and alternative forms of collaboration o ered a new way of producing a ordable and flexible forms of housing.

It’s very clear that great examples and precedents exist. Perhaps the true challenge is in how these can be more than just exceptions, how they can challenge the current housing environment and o er another kind of housing standard that is not defined primarily by market interests. With this in mind, in this session we wanted to discuss how we can find new strategies for a broader implementation of good housing and what the main obstacles are. I think part of this rethinking of strategies is also, perhaps, to challenge the traditional role of the architect. We’ve already seen this a lot in the topics recurring in previous sessions of this Symposium. For example, Clare Cousin’s talk on the Nightingale project is a very interesting example. The practices we are going to hear from in this session have all taken on roles that are often considered outside the traditional discipline of architecture—for example, as the developer or the community activist or the economist. In doing so, they had to negotiate with municipalities, planners, builders, policy documents, regulations, legislations and, of course, the inhabitants, while all the time trying to form and define alternative models of organisation and production and facing the many obstacles I mentioned in this process. Finding new strategies is a di cult and complex topic, but at the same time it’s a very urgent one.

I’m going to introduce all of our speakers. First up, we have Anne Lacaton and JeanPhilippe Vassal, the Garry and Susan Rothwell Co-Chairs in Architectural Design Leadership here at the Sydney School of Architecture and the Pritzker Architecture Prize laureates of 2021. Their impressive practice spans more than three decades and includes projects for a ordable housing, cultural and academic institutions, public spaces and urban strategies. One thing that I really appreciate in their practice is this kind of refined sensibility for the existing conditions on a site, and how their work is always about the generosity and the luxury of everyday life that architecture can allow.

Our second speaker is Andreas Hofer, a Swiss architect trained at the ETH [Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule, Zürich]. He has been involved as consultant and project developer in numerous innovative cooperative housing projects in Zürich, such as the Kraftwerk 1 and the Mehr als Wohnen, the “More than Living.” He’s also been appointed as the artistic director of the International Building Exhibition in Stuttgart in 2027—very exciting to follow the development of that, Andreas.

Our final speaker is Florian Köhl. He’s an architect, teacher and founder of Berlinbased o ce fatkoehl. It’s a practice that has been committed to exploring alternative architectural production models in the Berlin housing market since the early 2000s. Köhl and his practice also played an important role in the Baugruppen movement at the time, designing and developing alternative models for housing, always in close dialogue with the future inhabitants. Köhl has taught and researched at the Technical University Berlin and the Bartlett School of Architecture, and he’s the co-founder of the NBBA [Netzwerk Berliner Baugruppen Architekten], which is a network of co-housing architects in Berlin. With that very brief statement about the session and even briefer presentation of the panel members, I am going to pass to Anne and Jean-Phillippe to present.

AL

Good afternoon. As we discussed in our Tuesday lecture, our ambition and our aim for housing in the city is that every dwelling should have the same facilities as a villa, should give people the same desire and pleasure as a house with a garden—even under conditions of density. We think that this applies to the construction of new housing but also—and this

New Propositions, Questioning Cost-Per-Square-Metre and Generosity 8

New

Questioning Costper-Square-Metre and Generosity

SYDNEY SCHOOL 9

Figure 1. Lacaton & Vassal, Maison Latapie, Floirac, France, 1993. © Lacaton & Vassal

New Propositions, Questioning Cost-Per-Square-Metre and Generosity 10

Figure 2. Lacaton & Vassal, Cité Manifeste, 14 social housing units, Mulhouse, France, 2005. © Philippe Ruault.

Figure 4. Lacaton & Vassal, Cité Manifeste, 14 social housing units, Mulhouse, France, 2005. Rendering © Lacaton & Vassal

3 See also Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal, “Living in the City: New Propositions, Questioning Cost-per-Square-Metre and Generosity,” Rothwell Chair Symposium 2021, Sydney School of Architecture, Design and Planning, streamed live on April 29, 2021. Refer to last page for link to recording. Slide shows photograph from June 2001 of the five teams of architects involved in the project called Cité Manifeste: Architectures Jean Nouvel; Shigeru Ban with Jean de Gastines; Anne Lacaton & JeanPhilippe Vassal; Duncan Lewis with Potin + Block; Mathieu Poitevin with Pascal Reynaud.

A statement reads:

FIVE TEAMS AND ONE WORKING METHOD. Experimentation must be plural. Pierre Kemp discussed the project with Georges Marios, the department’s consultant architect at the time, and decided to approach several well-known architects. He turned to Jean Nouvel, relying on the architect’s generosity and his previous experience in social housing. Building a dozen social housing units represents a large investment in time and a more than uncertain return. However, Jean Nouvel agreed, convinced that housing should once again become a primary focus of research for architects. He convinced Pierre Kemp to approach teams of young architects who shared this idea.

[Original in French.]

should occur simultaneously—to the transformation of the existing, to bring to it the same qualities as the new, in every case, without consideration of “categories.” This means to go beyond the standard to provide extra space—outdoor space, to build larger, to give more square metres—a kind of a ordable luxury to make everyday life more pleasant and density acceptable, or even a quality. The economy is a key factor in making all this possible and a ordable, to build more generous spaces at the same cost and to live in more spaces at the same rent.

The first house we built in France 30 years ago is based on those principles (fig. 1). It’s a house for a family of workers in a suburb of Bordeaux. The house o ers 180 square metres, while the family was expecting the 70 square metres provided by a standard house out of a catalogue. To achieve this goal, we studied every element of the construction very carefully to maximise its e ciency, to use less material and never compromise on our initial goals of generous space and quality of life. We studied it to make the construction simple and easy to build, to build more space with less.

The house works with the climate, with a large greenhouse. It is a passive house, which spends little energy. Again, 180 square metres—€65,000. As young architects, it was our first project, and we were really, really committed to achieving all these ideas. It was a great opportunity for us to study this house and to understand most of the criteria and arguments in order to achieve these ideas. After years, the house o ers a lot of freedom to the inhabitants.

The next project, in Mulhouse in the east of France, was for 14 dwellings developed with a social housing company (fig. 2). This project was the opportunity for us to bring the qualities and the generous space of House Latapie into a more collective form. The plot was the site of an old factory in the middle of one of the biggest housing schemes for city workers in Europe, built from the middle of the 19th century. The original typology consisted of square houses divided into four apartments of 36 square metres (fig. 3). Time after time, they have been transformed according to the needs of the families, so it made a great collection of these kinds of houses.

The project was also very innovative in terms of strategy and method, because we were five teams of architects, and the client was really involved in inventing something in terms of new social housing.3 We all—clients and architects—worked together in a very collaborative way in the discussions on the projects, and we also made decisions together. The client was very open to any proposal. The only constraint was the budget for the construction of these 60 dwellings, which we had to respect because it’s a publicly subsidised social housing company (fig. 4).

Our design proposed apartments almost twice as big as the standard of social housing. For that, we used very simple construction systems, like first building a big loft that was then divided into 14 apartments, each of which had two floors: the ground floor and the first floor (fig. 5). The ground floor is like a big platform on which three ranks of greenhouses are built. Every dwelling has a space on the ground floor and a space on the first floor.

The agreement with the client was very clear. On our side, we committed to respect the budget, even if the construction and the apartment were much bigger than the standard of social housing. On his side, he committed to renting the apartments at the standard rate, even though they were bigger. That is to say, the rent is fixed by type—two bedrooms, three bedrooms, and so on—independent of the surface area of the house (fig. 6). That was a very important agreement to make possible this project as social housing.

This is the final result, again, with the principal of the greenhouse and double envelope. The house is a passive construction that maximises natural ventilation and sun capture through the conservatory, with large glass windows as well as thermal curtains to ensure comfort. This approach delivered 14 large apartments. It’s very interesting to see the subsequent appropriation that made all 14 di erent (fig. 7 and 8). For example, the surface of one four-bedroom dwelling, a duplex, is 187 square metres including the winter garden

SYDNEY SCHOOL 11

Figure 3. Nineteenth Century Workers Housing, Mulhouse, France. © Lacaton & Vassal

SUMMER / DAY

Doors opened

Curtains*: shading

Curtains*: shading

WINTER / NIGHT

Curtains* closed

curtains* closed

Shading & energy saving screens** closed Warmed up inside

Large natural ventilation

Doors opened

Curtains*: shading Insulation

Shading & energy saving screens** closed Conservatory

MULHOUSE CONSERVATORY HOUSING

Doors closed

Curtains* closed

* Isolating and shading sliding curtain with reflecting external face and slim isolator – textile inner face ** Climate screens made of aluminium strips with open spaces in between : reflect sun radiation the day and retains convective heat during night time

New Propositions, Questioning Cost-Per-Square-Metre and Generosity 12

Figure 5. Lacaton & Vassal, Cité Manifeste, 14 social housing units, Mulhouse Conservatory Housing, France, 2005.

SYDNEY SCHOOL 13

Figure 6. Lacaton & Vassal, Cité Manifeste, 14 social housing units, Mulhouse Conservatory Housing, France, 2005.

New Propositions, Questioning Cost-Per-Square-Metre and Generosity 14

Figure 7 and 8. Lacaton & Vassal, Cité Manifeste, 14 social housing units, Mulhouse, France, 2005.

[Left]: Photograph by Philippe Ruault. [Right]: Photograph by Lacaton & Vassal.

(46 sqm), while the standard for this typology was 100 square metres. The cost of construction was €90,000 net, exactly the same as the cost of a standard of 100 square metres. It was rented in 2005 for €467, the rent of a standard apartment in this city.

On the ground floor there is an access, which is a garage, but that can be used—if there’s no car—as a normal room, two bedrooms, and stairs. On the upper floor, there is a large space with a big living room of 50 square metres, two large bedrooms and the large winter garden of 45 square metres, which is like a private external space in the house (fig. 9). There are no partitions on the ground floor and the first floor because, although we tried to do this, the inhabitants didn’t want them—they arranged their own intimate spaces—and because the oversized space and the connection with the winter garden on the same level, along with large sliding glass doors, the greenhouse, the ventilation systems and solar curtains, acted as an e cient climatic bu er zone, providing good levels of comfort in summer and winter (fig. 10). It’s a very simple system. Together with the winter garden, which is also an extra space for use, this represents very good e ciency in terms of saving energy and climatic comfort.

Here, the neighbouring apartment is exactly super-imposed (fig. 11). It is also a fourbedroom dwelling with the same construction cost and the same rent as a 100-squaremetre standard house. You can see there the system of glass windows and thermal curtains. Here it’s the opposite plan. The ground floor is a living room and two bedrooms, while on the upper floor there are two bedrooms. Real luxury is not being constrained in everyday life—to have di erent tables where you can work, eat lunch or play. This is real luxury in everyday life, not being constrained to do something at the same place every day.

SYDNEY SCHOOL 15

New Propositions, Questioning Cost-Per-Square-Metre and Generosity 16 Chambre 1 12,1 m2 Chambre 2 10,1 m2 Garage + entreª 22,7 m2 Chambre 3 15 m2 Chambre 4 13,7 m2 Sª jour / cuisine 50,8 m2 Jardin d'hiver 45,8 m2 RDC R+1 01 5

Figure 9. Lacaton & Vassal, Cité Manifeste, 14 social housing units, Mulhouse, France, 2005.

SYDNEY SCHOOL 17

Garage 14,3 m2 Chambre 1 10,3 m2 Chambre 2 14,1 m2 S™jour / cuisine 65,7 m2 Chambre 4 11,5 m2 Chambre 3 10,6 m2 Jardin d'hiver 19 m2 RDC R+1 01 5

Figure 10. Lacaton & Vassal, Cité Manifeste, 14 social housing units, winter garden, Mulhouse, France, 2005. © Lacaton & Vassal.

Figure 11. Lacaton & Vassal, Cité Manifeste, 14 social housing units, Mulhouse, France, 2005.

New Propositions, Questioning Cost-Per-Square-Metre and Generosity 18

Figure 12–14. Lacaton & Vassal, Cité Manifeste, 14 social housing units, Mulhouse, France, 2005. Film Still from the documentary Constructing Escape: A Story about Air, Void and Light, Anne Lacaton and JeanPhilippe Vassal directed by Karine Dana, 2019. © Karine Dana.

It’s 20 metres deep, which allows some areas to be darker so you can work on the computer or watch TV. The space on the upper floors is smaller, with the garden. These are very recent pictures that we took (fig. 12–14). The person who lives there is drawing cartoons for children. It’s a place where they work but also where they live. It’s very interesting to hear what they say about their house and how they live every day. Here the garage is not used as a garage, but as an extra space. There is a small place for books in the darker area, and the upper floor provides a place to rest under the greenhouse. Jean-Philippe will continue.

JPV

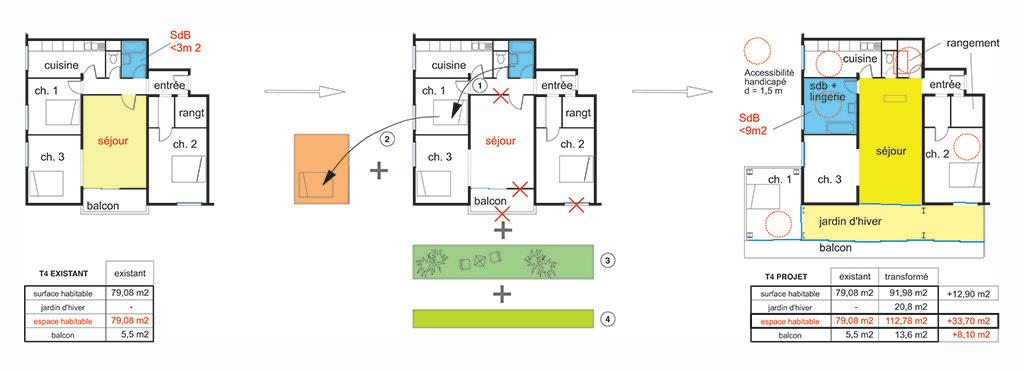

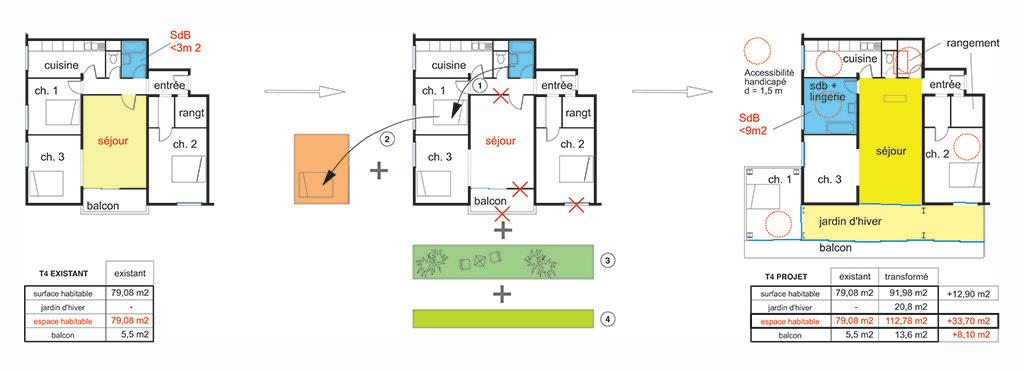

I will continue with a project in Saint-Nazaire, in the west of France, close to the ocean. It’s about the transformation of the existing that o ers the opportunity of good and a ordable housing and also the possibility of densification, from inside and case by case. The project we had to work with was this building. It has ten levels with four apartments per floor (fig. 15). In the plan, we have two type 4 and one type 3 and one type 5 in yellow (fig 16). If we take the original plan: from the entrance, you have a very, very small bathroom—less than three square metres—in the existing, a small living room and a small balcony. Our intention was to take this very small bathroom and place it in one bedroom, and then it makes a big bathroom of nine square metres. The original bathroom could become storage. Since we lose one bedroom, we have to make one more bedroom outside, close to this bedroom. We can take away the small balcony, add a new winter garden and a new balcony, to propose a new flat with much more qualities.

We see here the four starting points for the four apartments on the original, on the existing (fig. 17). Then, in an intermediate phase, all the bathrooms went to places with more space, open to the outside. Here we provide some extension for the extra bedrooms plus the winter gardens.

At the same time, there was an opportunity for densification. Instead of the four apartments per level—40 apartments in total—of the existing building, it was possible to add 20 apartments on one side and 20 apartments on the other side. This would create the possibility of extensions with winter gardens, new bedrooms and new locations for the bathrooms. So, instead of only one core, we now have three cores, one existing and two others. Here is one of the existing cores that is accessed from the new one.

Here, we see the extension of winter gardens and new bedrooms from the existing building, plus the provision of the same number of flats in addition to the existing—40 plus 40 (fig. 18). This gives us 80 flats at the end. Car parks are superimposed to account for the increased number of cars and activities. So, the plan that was like that, becomes like this (fig.19).

SYDNEY SCHOOL 19

Figure 15. Lacaton & Vassal, Housing Transformation, Saint-Nazaire, La Chesnaie, France. © Lacaton & Vassal

New Propositions, Questioning Cost-Per-Square-Metre and Generosity 20

Figure 16. Lacaton & Vassal, Housing Transformation, Saint-Nazaire, La Chesnaie, France.

SYDNEY SCHOOL 21 T3g T3h ch. ch. ch. ch. sdb sdb T3c T4b T3a T3d T3e T2f sdb sdb sdb ch. ch. ch. ch. sdb cuis. cuis. cuis. cuis. ch. ch. 130,3 m2 135,6 m2 112,8 m2 113,3 m2 ch. ch. ch. ETAGE COURANT - PROJET APPARTEMENTS TRANSFORMES LOGEMENTS NEUFS T4 T5 T3 T4 T3+ T4 ou T3+ T4 ou T3+ T4+ ETAGE COURANT EXTENSION PRINCIPE T3 T3 T3 T2 1 escalier + 1 ascenseur 3 logements par palier 1 2 3 1 1 escalier + 1 ascenseur 2 logements par palier 2 1 escalier + 1 ascenseur 2 logements par palier 3 ETAGE COURANT EXISTANT T4 T5 T3 T4

Figure 17. Lacaton & Vassal, Housing Transformation, Saint-Nazaire, La Chesnaie, France.

Figure 18. Lacaton & Vassal, Housing Transformation, Saint-Nazaire, La Chesnaie, France.

Figure 19. Lacaton & Vassal, Housing Transformation, Saint-Nazaire, La Chesnaie, France.

New Propositions, Questioning Cost-Per-Square-Metre and Generosity 22

Figure 20. Lacaton & Vassal, Housing Transformation, Saint-Nazaire, La Chesnaie, France. © Philippe Ruault.

Figure 21. Lacaton & Vassal, Housing Transformation, Saint-Nazaire, La Chesnaie, France. © Philippe Ruault.

Figure 22. Lacaton & Vassal, Housing Transformation, Saint-Nazaire, La Chesnaie, France. © Philippe Ruault.

4 See also Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal, “Living in the City: Transformation, Intensification.” Rothwell Chair Symposium 2021, Session 1, Sydney School of Architecture, Design and Planning, streamed live on April 27, 2021. Refer to last page for link to recording.

GRAND PARC, BORDEAUX 3 BLOCKS, 530 DWELLINGS TRANSFORMED

100 % EXISTING CONSERVED

20% heavy renovation (hallways, elevators, bathrooms, elect. )

80 % light renovation

+ 53% SURFACE ADDED

+ 50 m2/dwelling usable surface on average incl. Dwellings + winter gardens + balconies + interior cellars

- 60% PRIMARY ENERGY CONSUMPTION

48,8 kWhep/m2.year after transformation (divided by 3) (low energy building)

- 50% CARBON FOOTPRINT (- 26.000 T. CO2eq)

Transformation (26.380 T.CO2eq) – Demolition & rebuild (52.400 T.CO2eq)

100% BUILDING OCCUPIED DURING THE CONSTRUCTION WORKS

NO MOVE OF THE INHABITANTS

0% INCREASE OF RENT + CHARGES (5 to 7 €/m2)

52.000 € NET / DWELLING / cost of construction works for the transformation

160.000 € ESTIMATED COST FOR DEMOLITION & REBUILD

80 % FUNDED BY THE SOCIAL HOUSING COMPANY AQUITANIS (owner)

20% PUBLIC SUBSIDIES

We could also consider the whole plot. On this site, we have 312 existing apartments. With a density of 60 dwellings per hectare and this kind of densification and transformation, we can a ord to create 200 new dwellings. This not only increases the density, but also retains all the park—not one tree would be cut down, thus keeping the site interesting. In other words, it is possible to densify, to create, while providing more quality for the apartments and without the need to make any new street, new road or new network. It is possible to densify the situations from the existing, so there is no need to buy new flats or new spaces or new land—the same territory can be densified and extended (fig. 20). You see here, from the construction of the existing building and the addition of new winter gardens and extensions, it is possible to propose a situation in which 40 flats at the beginning become 80 flats at the end (fig. 21).

The work takes place from inside the existing flat. We take away the old façade. We create the extension towards the outside, providing this bu er zone and winter garden that improve both the quality and the energy consumption and o er interesting places for families to live in and to discover (fig. 22). By working with the climate, this bu er zone o ers better winter energy consumption as well as creating shade in summer.

For us, the question of a ordability has to be considered in the context of the general economy of the city. It depends on the decisions made about urbanism, on regulations, on political factors, and is not only about the cost of building consumption or priceper-square-metre as defined by the market. A key issue is to work with the existing. It is about the economy of the transformations. We have seen it in the Grand Parc project in Bordeaux that we showed in session 1.4 From an existing situation, it is possible to transform and to propose a much better situation. Here we can see precisely the transformation of three blocks and 530 dwellings with 100% conservation of the existing: 53% of additional surface area; 60% reduction in primary energy consumption; and 100% occupation of the building during the works (fig. 23). The rent has not changed, the rent plus charges remains the same. In fact, the cost was €50,000 per dwelling, whereas the cost of demolition and rebuilding would have been €160,000—more than three times more. Moreover, 80% of this project was funded by the social housing company and 20% by public subsidies. At a national level, the program of urban renovation in France developed as a policy of demolition and reconstruction at a cost of €165,000 per dwelling. Today, it’s nearly €200,000 per dwelling. From 2006 to 2015, they demolished 125,000 dwellings to rebuild only 100,000 dwellings. That is a loss of 25,000 dwellings, when there is an important need in France for new dwellings. So, for a cost of €16 billion, we lose 25,000 dwellings.

SYDNEY SCHOOL 23

Figure 23. Lacaton & Vassal, Druot and Hutin, Data Sheet, Grand Parc, Bordeaux, France, 2017 .

In the alternative of transformation, instead of €165,000 it is €55,000 per dwelling. In other words, in one case we lose 25,000 dwellings; in the other case, with the same amount of money, it is possible to transform 300,000 dwellings in good condition.

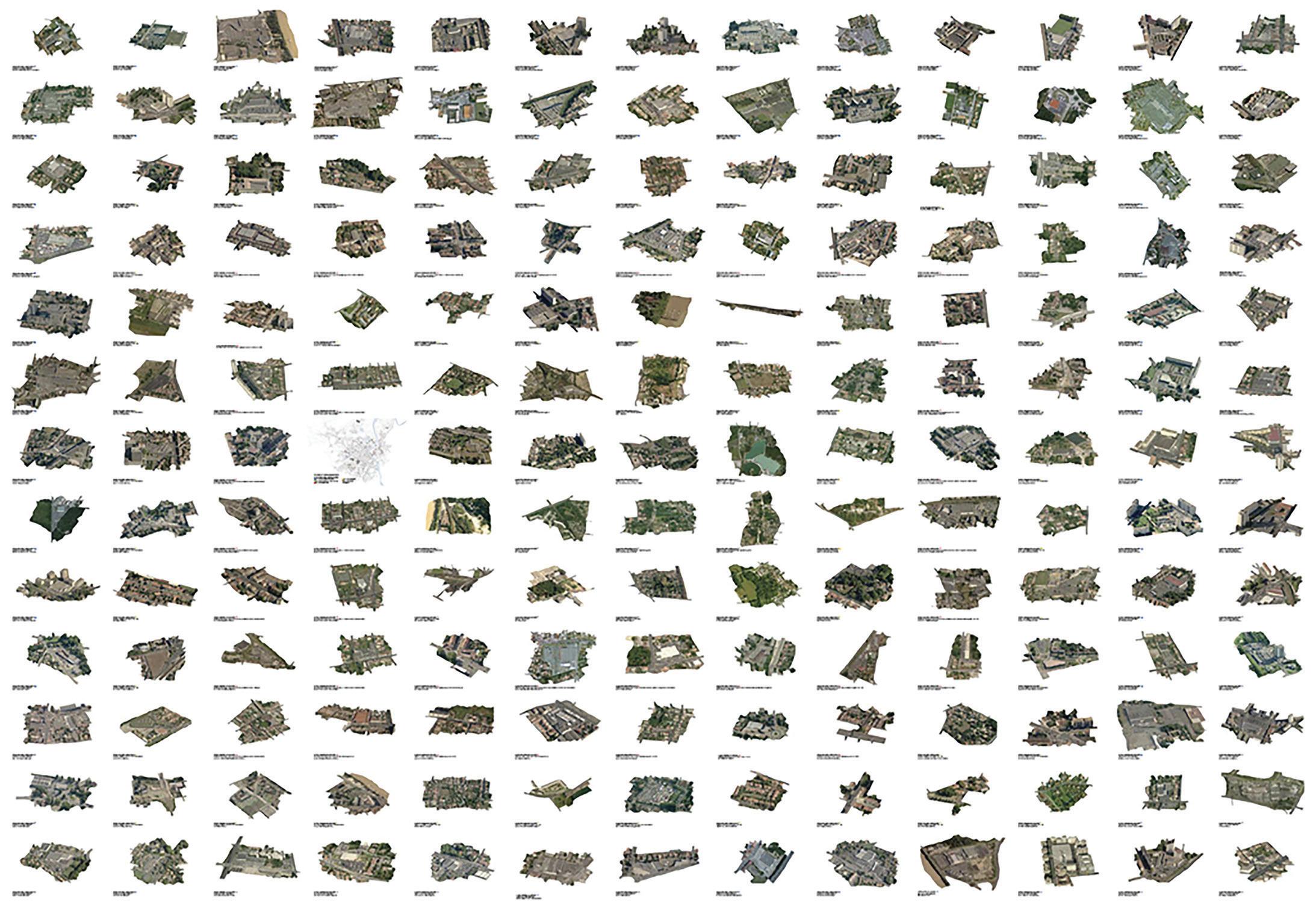

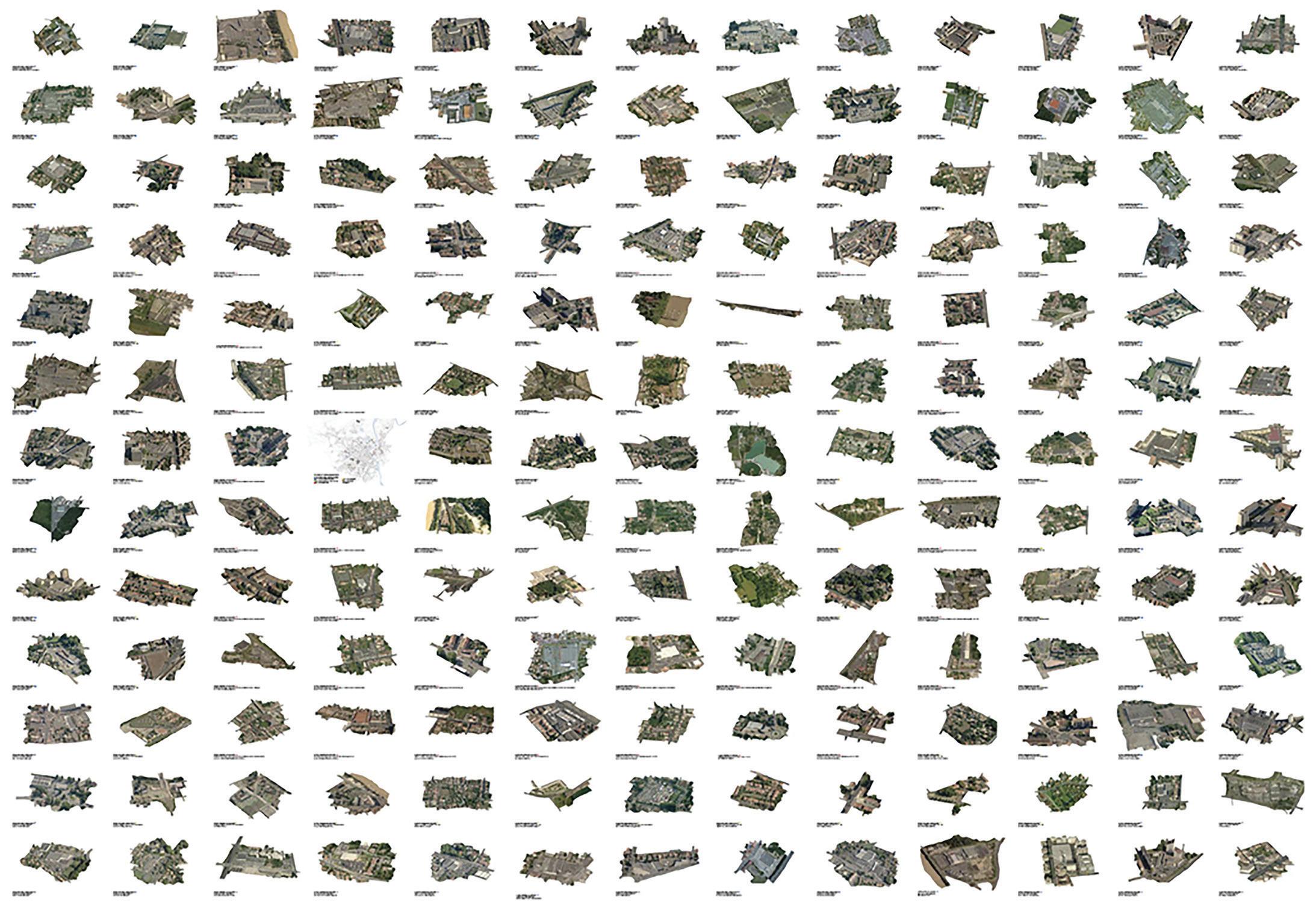

It’s about precision. It’s about considering the city and the existing city as a collection of what we call situationes urbaines capables, which means urban situations with capacities, precisely, case by case, place by place, area by area. We have hundreds and thousands of them (fig. 24). We can consider each case precisely in order to see how we can improve the existing and at the same time create new dwellings. Every dwelling, every building, can be transformed. Every dwelling, every building, every plot can be increased. In this way we can achieve a sustainable and qualitative densification for the benefit of living spaces, uses and inhabitants.

Frédéric Druot, our friend and partner on this topic of transformation and the idea of PLUS, has undertaken over five years an inventory of places around Paris, at the periphery of Paris, inside the péripherique. In this inventory, he has identified the capacity for transformation and densification of 1,600 sites for collective housing. This equates to 450,000 occupied existing dwellings that can be transformed and, at the same time, the possibility of building 135,000 new additional dwellings. It is PLUS Paris. It seemed to us possible to deal with these questions of a ordability, rents or cost-per-square-metre and, at the same time, to propose high quality housing, to do the maximum with the minimum cost, to consume as little energy as possible and to do so e ciently. We dream that it is possible to do it with any kind of organisation: social housing companies, associations of inhabitants, cooperatives, Baugruppen or private developers. It can be for rent or for sale and can create the best conditions for mixing. The only condition is to do the maximum. Thank you.

HF

Thank you very much, Anne and Jean-Philippe. With that, I will pass the floor over to Andreas Hofer.

AH

I invite you to Zürich in Switzerland, the city where I lived for 30 years. I will first present a project we worked on there and then move to Stuttgart, where I have lived for the last three years. I want to discuss some questions that are, I think, universal in our modern cities. I will talk about cooperation, about cooperatives. I’m convinced that we can only change city life and adapt to the new challenges if we do it together.

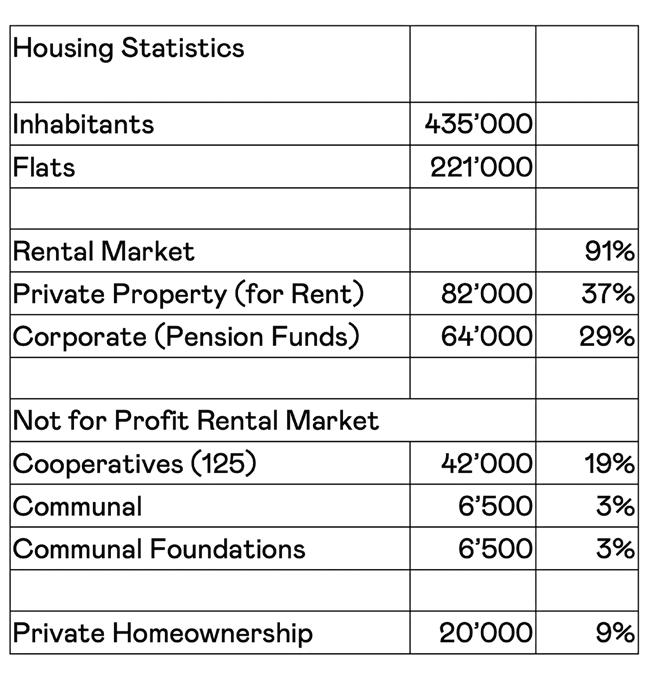

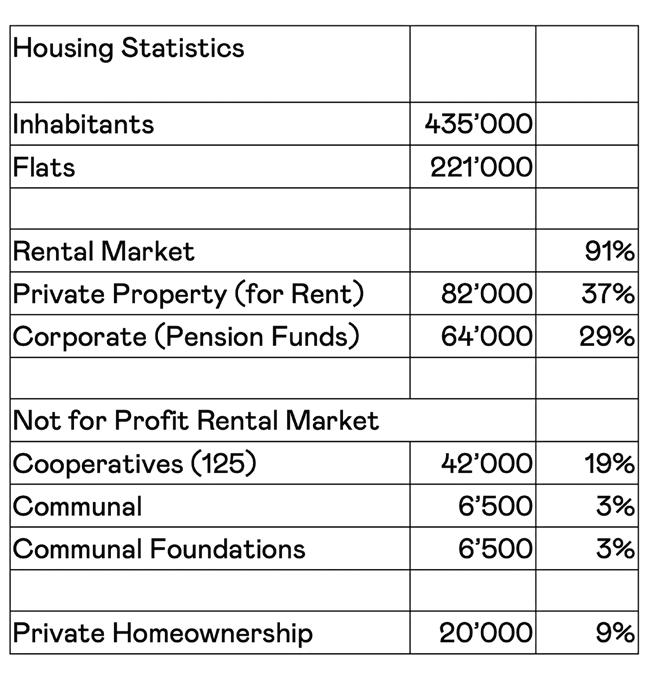

This is the city of Zürich, founded by the Romans 2000 years ago where the river Limmat emerges from the lake of Zürich, with the Swiss mountains in the background—a very natural, beautiful place. Zürich was radically transformed at the end of the 19th century, when modern industry and modern infrastructure began to be introduced (fig. 25). You see, on the right side, how this speculative housing then took over the city, together with the factories that grew in this valley. It was a kind of explosion of the city, which generated many social problems for the people who came to find work there. This was a revolution, which led in 1907 to the enactment of a law regulating the Zürich housing market. This law forced the city to provide a ordable and healthy housing to the people. This was the first settlement, which was built from 1907 to 1914.5 Today these are listed buildings. This was the beginning of a wave of thinking about how urban life could be organised for the people. These are some figures (fig. 26). What really is astonishing is that until now, in one of the richest cities of the world, 91% of housing is in the rental market. Only 9% of homes in Zürich are privately owned, and the not-for-profit rental market accounts for 25% of the whole market. Much of this is in the form of cooperatives and 6% is communal housing. This is not social housing. Cooperative housing is not social housing, but housing that developed from self-help organisations. This is the problem. These self-help organisations built

New Propositions, Questioning Cost-Per-Square-Metre and Generosity 24

Andreas Hofer

More than Living, Zürich: Sustainable Housing Cooperatives and IBA 27

5 Slide shows a photograph of city blocks with 5-storey residential buildings from the early twentieth century in Zürich, Switzerland.

SYDNEY SCHOOL 25

Figure 24. Frédéric Druot, Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal, PLUS: Paris, 2015.

New Propositions, Questioning Cost-Per-Square-Metre and Generosity 26

Figure 25. Aerial photograph taken from a balloon, Zurich, Switzerland.

Photograph by Eduard Spelterini, 1898. Baugeschichtliches Archiv Zürich.

Figure 26. Housing Statistics Zurich, Switzerland, WBGZH 2016–20, overlay diagram by Andreas Hofer.

SYDNEY SCHOOL 27

Figure 27. Meeting, Hunziker Areal, Zurich, Switzerland, 2015.

Photograph by Andreas Hofer.

Figure 28. Kornelia Gysel, Sabine Frei, Anne Kaestle, and Dan Schürch. Häuser im Dialog: Ein Quartier entsteht. 2015. [Houses in Dialogue].

Photograph by Kornelia Gysel

up the housing stock over a very long time, so the a ordability is a result of continuity. This makes it so di cult today to try to solve housing issues, if you don’t have this tradition, if you don’t have the housing stock. And it’s very, very expensive to buy back from the private housing market. This is a question we are actually discussing in Germany.

To celebrate this strong tradition, in 2007, the modern 120 cooperatives of Zürich decided to demonstrate what they had learned over the last 100 years and to identify questions for the future. This project, which was called Mehr als Wohnen—More than Living—involved more than 50 existing cooperatives. They founded a new cooperative to demonstrate, to experiment and to cooperate on every level. The city of Zürich provided this plot of land at the periphery of Zürich. It was an industrial site, and the neighbourhood is not easy. There are some quite problematic residential areas, it has a rough industrial atmosphere, and it lacks infrastructure. So, the project was about city making, and the creation of neighbourhood was important.

From the initial phases, there was much discussion in the old factory building, where people met, where architects gathered. It is not a Baugruppe—these were not people who wanted to live there. It’s more about political interest in how the city could be transformed, what we should build there. This is perhaps an important di erence to the projects that Florian will present afterwards. We also tried to bring architects into a dialogue (fig. 27). We invited 25 architectural practices to propose a kind of master plan and to only draw one building in it. Then we brought together the practice that won the competition, Futurafrosch Duplex, with three other firms with di erent propositions. We began with a dialogue phase, as we called it—half a year of collaboration with the architects, with many specialists. At the end, we brought together these di erent ideas, these di erent architectural practices, into one project. This was very important. The architects called it “the dialogue of the houses.” Here you see a workshop with di erent architects standing around a huge model. They really worked on their houses in an e ort to identify rules and create a whole form.

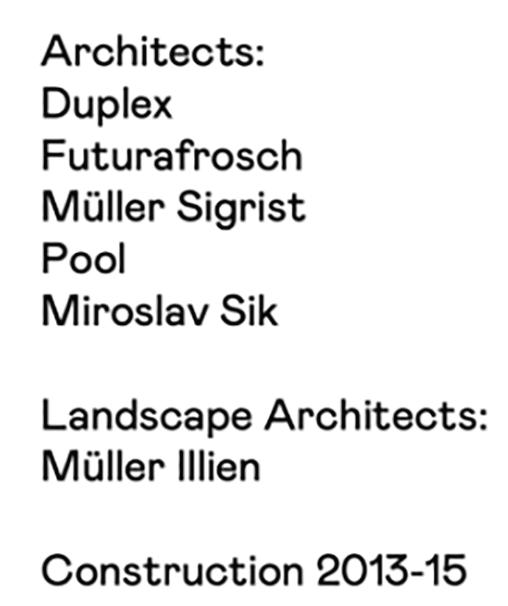

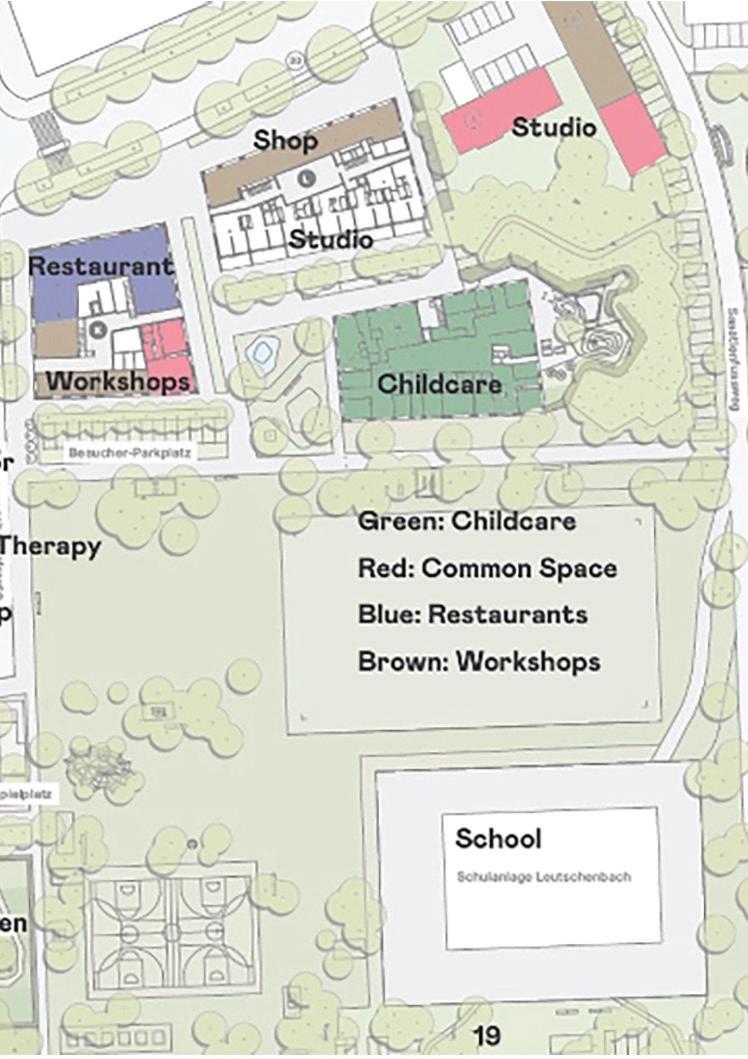

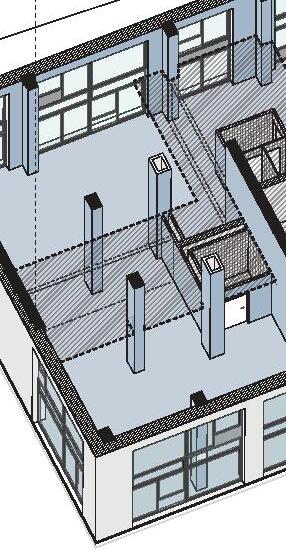

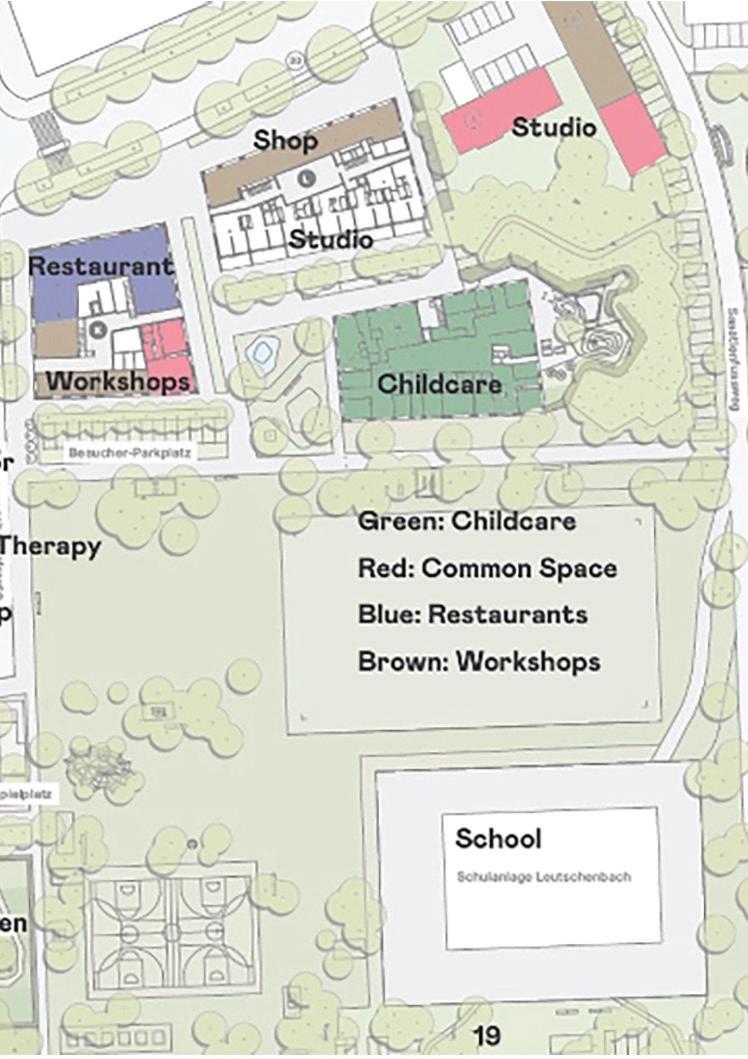

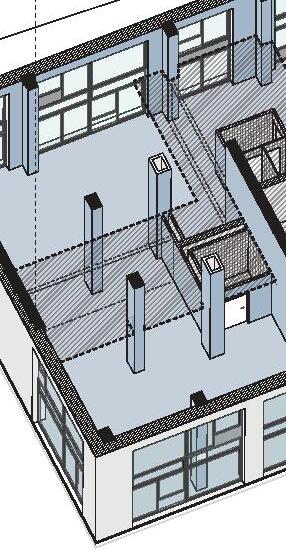

At the end, this little booklet, Häuser im Dialog—Houses in Dialogue—was presented by the architects (fig. 28). This was the rulebook for the ongoing work until construction and completion. It’s a lot about density, it’s a lot about urbanity—how you can create a dense place that is complemented by a lot of green space (fig. 29). You could say, then, it’s about density and liberty. This is also true on the house scale—the houses are impressively deep and big, which has much to do with economy, as Anne and Jean-Philippe demonstrated. If you make the houses bigger, then you get e ciency that is a surplus for the inhabitants. Take this staircase, for instance. This is very a ordable housing, people without much money live there, but we could o er them these communal spaces (fig. 30). Here you see the 13 houses and the di erent architects and landscape architects who were involved (fig. 31). The project was built from 2013–15 and I had the pleasure of serving on the board of directors for three years after completion. This is a very special moment for an architect, if you don’t leave the project when it’s finished but remain part of the process. I learned much about how people moved in, how people adapted to the flats. You have seen these beautiful images of Mulhouse. We also have many of these in these houses. You see that the houses are big, and that every house is di erent. However, there are some elements of cellularity. We worked with this cluster concept to see how, within a compressed space, you could o er small one-person and couple households, and put di erent cells together to form these huge floors, where people can interact in communal spaces. So, it goes from the private space to a kind of semi-private neighbourhood, to the house, to the houses and, finally, to the city.

This is how people moved in and took over these spaces. We tried to bring luxury to daily functions. The laundry facilities are beautiful and accessible spaces at the entrance hall (fig. 32). We naturally discussed mobility. There is a radical reduction in car ownership in this project, but there is infrastructure for bikes and cargo bikes, and car sharing. This is an investment in a more sustainable future.

New Propositions, Questioning Cost-Per-Square-Metre and Generosity 28

SYDNEY SCHOOL 29

Figure 29. Hunziker Areal, Zurich, Switzerland, 2015. Photograph by Johannes Marburg.

Figure 30. Hunziker Areal, Zurich, Switzerland, 2015. Photograph by Johannes Marburg.

Figure 31. Plans and participating architects, Hunziker Areal, Zurich, Switzerland, 2015.

New Propositions, Questioning Cost-Per-Square-Metre and Generosity 30

Figure 32. Communal laundry, Hunziker Areal, Zurich, Switzerland, 2015. Photograph by Flurina Rothenberger.

Figure 33. Andreas Hofer, site plan, Hunziker Areal, Zurich, Switzerland, 2015.

A little hotel with a reception that is financed by renting out the hotel rooms, which the people who live there can also use for their visitors. The reception is the central station where people can meet. It is open every day. There you can collect the key for an electric car or for a cargo bike. There you can rent communal facilities and rooms. You can also get help there, for instance. if you don’t speak German, if you need to fill in a form, if you have any household or technical problems. It’s very important to have this caring facility in the settlement. Some 1,300 people live there and about 200 work there, so the scale allows you to have this infrastructure.

A great deal of work went into the concept of the ground floor (fig. 33). We tried to invent a neighbourhood on the ground floor level to bring in a bakery, a restaurant, o ces, spaces for cultural activities, such as dance, and childcare. Nobody thought that this would work so fast and so well, to fill up these spaces and to have a dynamic of change and acceptance of these spaces. Many people have their little shops, their little o ces here. It also has much to do with a local economy, local sharing and local help.

There is even discussion of providing food. There are communal gardens. There are also individual gardens. One year after people moved in, there was an opportunity to rent a commercial garden in the neighbourhood, and this is now also part of the project. Food production on a nearly industrial level is possible, and children can learn where the vegetables come from, and people can spend their weekends there. It’s a kind of datcha concept in the neighbourhood.

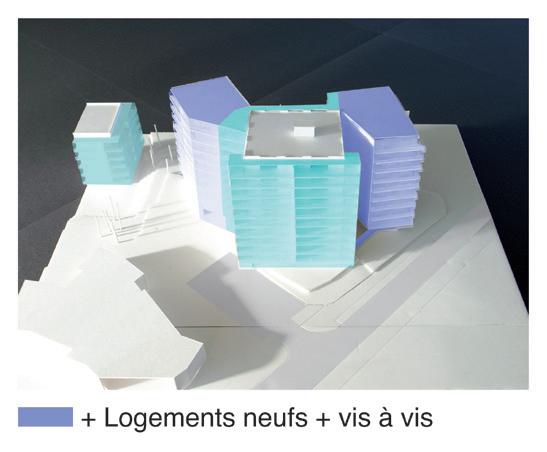

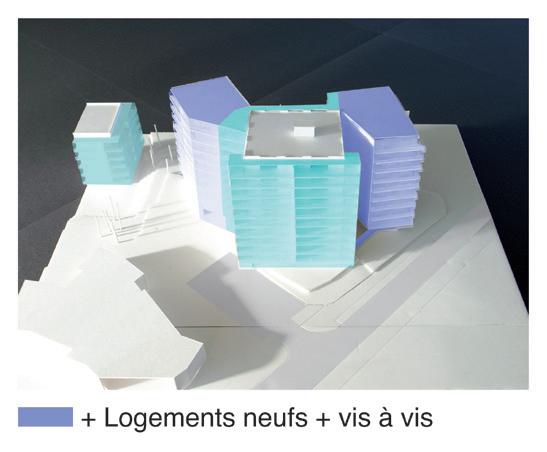

After this experience, I was elected three years ago as the artistic director of another centenary—a hundred years of Weissenhofsiedlung. The region of Stuttgart decided to celebrate this century with, again, a building exhibition (fig. 34). These German building exhibitions were really important in the 20th century. Remember 1986/87 in Berlin or the Ruhr area building exhibition around 2000? They were very special moments for architectural discussion as well as for regional development. It’s an honour for me 100 years after Weissenhof to discuss the role architecture can play in society on a bigger scale. It’s a regional project, not just a housing settlement. Naturally, it’s also a critique of modernist planning rules, on this separation of functions. We try to deal with this heritage, and we also try to invent new rules for the future. I will briefly introduce you to the themes and spaces— as we call them—we are working on. There are actually quite a lot of projects in the region.

SYDNEY SCHOOL 31

Figure 34. Weissenhofsiedlung Stuttgart, 1927. © Strähle Luftbild, Schorndorf.

New Propositions, Questioning Cost-Per-Square-Metre and Generosity 32

Figure 35. IBA 27 Network, map city/region Stuttgart.

Figure 36. Artwork IBA 27, L2M3, Max Guther.

This is the region of Stuttgart (fig. 35). It’s a metropolitan area of 2.8 million residents and a lot of industry—for instance, Daimlers and Porsches are produced here, as well as other machinery. It’s one of the most productive and most wealthy regions in Europe and is currently undergoing a spatial transformation process. Of course, industry is currently undergoing change, so we are dealing with a historical moment. Here you see this landscape and the 14 IBA projects we have developed so far. Some more are in preparation, and we hope to eventually present 25-30 concrete interventions by our exhibition year in 2027.

We hope that there will be 25-30. We are dealing with many di erent issues—with the politics and the people who live there—trying to find projects that can lead us into the future.

The main focus is on the transformation of the productive city and changing infrastructure. This is one of our biggest projects in Fellbach, a city in close vicinity to Stuttgart— an industrial area of more than 100 hectares, including huge parking lots, shopping centres, high-tech manufacturing and intensive agriculture that will be densified and transformed into a new neighbourhood. It’s a bit outside the city, but it will change this completely mono-functional and not very attractive space into a mixed-use area.

The future of city centres has, of course, acquired a new dimension with COVID. City centres are changing. Retail is under pressure. Now, we have an opportunity to acquire this multi-storey carpark in the middle of the medieval city of Stuttgart, which will be empty in two years. We are studying whether we can reuse the structure by converting it into a neighbourhood centre, with a ordable housing and with facilities and functions for the social groups that live in this neighbourhood. It is quite a symbolic idea for a problematic neighbourhood, which has been fragmented not only by this carpark but also by huge roads and previous demolition. It’s an opportunity for a kind of healing action.

We discussed places of movement and meeting, linking infrastructure to the city centres, densifying, and perhaps providing services so people don’t have to travel through the whole region, but can have places here for co-working and childcare, close to public transport nodes. The project is called Bahnstadt, Railway City. These huge empty spaces around this railroad station will be converted into a new neighbourhood.

In a city 20 kilometres away from Stuttgart, we are also dealing with the connection of green and blue infrastructure. The Neckar River that traverses the region tells the story of industrialisation: polluted, inaccessible, and poor water quality. How can we adapt this infrastructure system to climate change? How can we integrate new kinds of water management into the city to relieve some of the problems of water pollution? How can this waterway become a symbol for a more sustainable future?

The last issue we are addressing is modern heritage. This naturally links us to Weissenhof but, for us, modernity is also the mass housing and the infrastructure of the 1960s and 1970s. Here you see a hospital complex that will lose its function due to a new construction in a di erent location. We are studying how we could convert this infrastructure—not demolish it, but convert it into housing, into co-working, co-living in the city of Sindelfingen. It’s eight hectares of space that will become available and which is looking for new functions.

I wanted to give you an impression of what we are dealing with. We produced these images with a Berlin artist (fig. 36). Our vision is to take the existing elements and try to reinterpret, to redefine them for a prosperous future for the region.

Thank you.

HF

Thank you very much, Andreas, for bringing us into two di erent contexts, both Zürich and a little bit of Stuttgart. That is very much appreciated. I’m going to pass over the microphone to Florian, the final speaker for this session.

SYDNEY SCHOOL 33

New Propositions, Questioning Cost-Per-Square-Metre and Generosity 34

Figure 37. Design session with the members of the cooperative. Spreefeld planning team. Spreefeld, Berlin, Germany, 2013. Photograph by fatkoehl architects.

Figure 38. Layout of the site including new public connections. Spreefeld planning team. Spreefeld, Berlin, Germany, 2013.

Thank you very much, Hannes, and thanks also to Anne and Jean-Philippe and the University of Sydney. It’s very interesting to come from Andreas’ idea of the IBA to another IBA that you mentioned before—the International Building Exhibition—this is Frei Otto—in Berlin. Within the context of the IBA, I think, he took the most radical steps to test new approaches for architecture. Anne and Jean-Philippe asked me to talk about one of our projects, the Spreefeld project, and about the idea of the Baugruppen.

What you see here is 20 years later. 20 years later, we have a similar image of what we’ve seen before. What you see here is a typical meeting for the Spreefeld project, a much larger project than the one by Frei Otto and in a very di erent context. I absolutely agree that inhabitation is the most wonderful challenge for contemporary architecture. What we as a practice are looking for and what we think architecture should provide is what I wrote down here: innovative models for living and working—you discussed it before—that also allow the kind of individuality that we need as well as the collectivity of being part of a larger system, and which can drive innovation in construction. We think that architecture should o er a form of spatial dialogue, engaging public and private space through porosity, since there is less and less public space. Architecture has to do more than just o er privacy, it also has to find use in existing infrastructure and vegetation. While this is an interesting approach, we also need new models of architectural production that give inhabitants a relevant role in making the city and new economic models that do not seek profit. We also have to think about the building after it’s finished, after completion, to protect space for inhabitation.

What you see here is a bit di erent to Frei Otto’s approach, in which he just put up these platforms and o ered people this amazing opportunity to build a city on top—a vertical city, in a way. I think, we have gone a step further through a lot of experience: the project I’m showing is more or less our last Baugruppen project after we had completed at least six previous projects. As you can see here, we already have a curator, someone who oversees the whole process and writes a kind of rule book for what the project wants to achieve. In comparison to Andreas’ project in Zürich, this whole process happened without any support from the administration. It’s a very typical Berlin phenomenon of civil engagement when people decide: if things don’t happen, let’s make them happen. One di erence is that this project has three architects. We work on one project, but we come from three practices with very di erent experiences of Baugruppen and with very di erent experiences of the questions I posed in the first slide.

The people you see here are an elected group of inhabitants who will live in the place but who will not be owners in the usual sense, but members of a cooperative. I think this makes the project much more interesting, because the power does not lie with the individual but with the cooperative. In this context, it is important to remind you why Frei Otto undertook his project at probably the most significant moment in the transformation of Berlin, namely, when the wall came down. Suddenly Berlin had to change within a very short time. Huge projects, mainly infrastructure, were carried out, mostly driven by government or huge cooperatives. Nevertheless, in 2002, after 10 years of reunification, Berlin had a crisis. Berlin was shrinking, people moved away, and the economy was in trouble. Of course, housing development lagged well behind. Here you see some completed flats, but the pace was slowing down. That’s the moment I decided to open an o ce in Berlin, which was, I think, in terms of getting a job, not a very clever idea.

This is what we found. There you see an image of the wall. This is the first version of the wall, which was composed of houses, and here is the west. The circle around this building shows that very early, after the wall began to be built, the west started to invest in the city. However, the east had a very di erent strategy. The GDR decided to build mainly outside the city and leave the core of the city as it was. As a result, when the wall was demolished—you can see all these yellow arrows—there were a lot of empty sites.

SYDNEY SCHOOL 35

FK

Florian Koehl Spreefeld, Berlin

We decided—here is an image of our first project—to buy a site right next to the wall, as you can see here. Then we realised we had to find a way of financing the site and the building. We started to learn about the Baugruppen, which seemed to be exactly what we were looking for. It involved engaging people in a cooperative moment once you have secured the land—only the building phase is called Baugruppe. Afterwards, any kind of model can be used to manage the building, such as ownership, cooperative, and so forth. We had to learn about all these di erent steps.

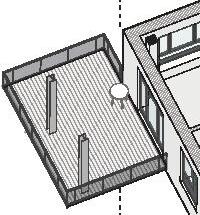

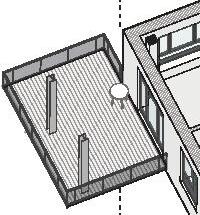

The project I want to show you, the Spreefeld—as the name suggests—is right on the river Spree which, at this point, was a part of the wall. The whole river was, more or less, a space for the wall. On the right-hand side you see Kreuzberg on the west and on the left-hand side you see the east. The site is a very typical site along the wall (fig. 37). Over the years, vegetation grew along the wall, because no-one was allowed to go there. The kind of vegetation that grew there is specifically related to this moment in time. Typically, these spaces were taken over by people (fig. 38). This is a very famous bar called Kiki Blofeld. These spaces were taken over and turned into a completely artificial beach. For us, then, the main question was, how can we access a place like this? Such an important space in the city—with the river, with the beauty of this greenery—has to be accessible, has to be public and, at the same time, we should create porosity (fig. 39). We should allow people to look from the river into the city and also allow sunlight to come from the south, so every inhabitant of this project would enjoy the whole richness of the place. At the same time, other people could also enjoy the richness of the place. This picture was taken last year. I had to ask the photographer to take it when the leaves were just emerging, because otherwise you cannot see the architecture (fig. 40). Taking pictures of the project was in fact the biggest issue for me over the last five years, because the greenery is so lush and can take over any minute. One of the things the architecture had to deliver was to keep every tree that was there. To achieve this, we created safety staircases to avoid the fire brigade having to come in. At the same time, we used them to allow people to experience that space from the outside. So, it became a really strong element in the project. It also allows you to reach the semi-private gardens on each building. These were important because, if you keep the whole ground for the public, you need to o er a certain amount of privacy for the inhabitant (fig. 41). This is a very prominent space in Berlin and it’s a very dense, very active space, so we had to provide quality spaces for the inhabitants to retreat to. Here, you see that every house has a semiprivate garden, and there are also huge private balconies that you can use as extensions of your space (fig, 42). They have a roof, but the inhabitants are free to plant them in any way. There is also the idea of a dialogue here—a building in dialogue with this dense and urban condition at this place in the city.

The red spaces you see here are mainly typical flats, the orange spaces are the so-called cluster flats, where people can share spaces and live together (fig. 43). A ordability comes through a very di erent idea of taking over space. Almost 25%of the project is in the form of these cluster flats and 13% of the space is for commercial units on the ground floor.

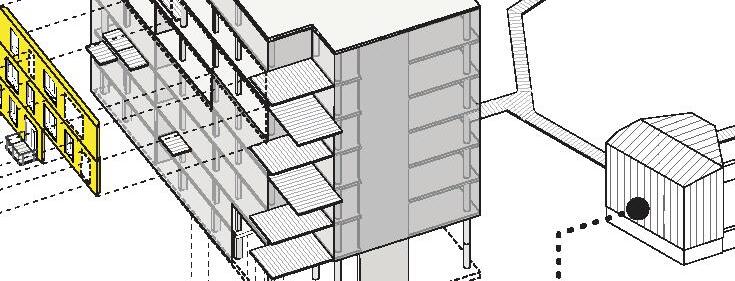

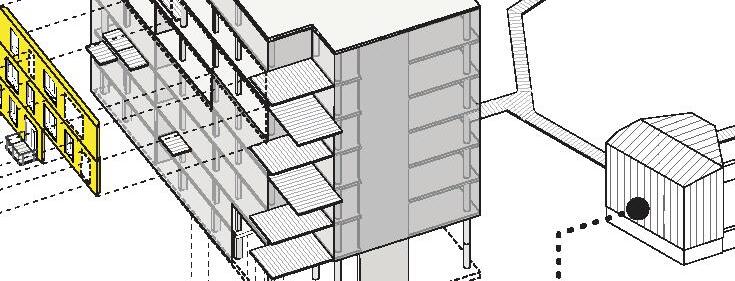

In terms of the structure and innovation, of how we can build more sustainably, we tried to find a minimal concrete structure for maximum di erence of use. At the same time, we had a prefabricated timber façade, one of the first timber façades in Berlin at that time.

The ground floor o ers two types of spaces (fig. 44). One space is a double floor unit space that can be used in many ways. Here you have the garden of the kindergarten. We tried to make this an active space that is safe because of how it is used, not because of a fence. On the right-hand side, you can see the o ce spaces (fig. 45). So, there are di erent uses of that ground floor space at di erent times of day—of course there are some architects’ o ces, so there’s also late-night use, as we know.

New Propositions, Questioning Cost-Per-Square-Metre and Generosity 36

STRUCTURE

die Zusammenarbeiter Gesellschaft von Architekten mbH

SKIN: PREFABRICATED TIMBER FRAMES passive house

Figure 39. Program/process/project: die Zusammenarbeiter Gesellschaft von Architekten mbH; architecture: carpaneto architekten, fatkoehl architekten, BARarchitekten. Structure and design principles, Spreefeld, Berlin, Germany, 2014.

CONCRETE STRUCTURE minimal structural elements maximal flexibility

Program, Process, Project: die Zusammenarbeiter Gesellschaft von Architekten mbH

Architecture: carpaneto architekten fatkoehl architekten BARarchitekten

SYDNEY SCHOOL 37 160 175 250 250 175 275 315 350 250 315 XS L XL S M CATALOGUE OF BATHROOM flexible location CATALOGUE OF WINDOWS modular use BASIC STRUCTURAL SYSTEM CENTRAL

OPEN STAIRCASE minimized circulation system 178x18=3204 88x18=1584 VERTICAL GARDEN

community

POWER STATION

SHAFTS ROOF-GARDEN for house

7

BARarchitekten

standard

HOUSE 3 silvia carpaneto architekten

fatkoehl architekten HOUSE 1 HOUSE 2

New Propositions, Questioning Cost-Per-Square-Metre and Generosity 38

Figure 40. Program/process/project: die Zusammenarbeiter Gesellschaft von Architekten mbH; architecture: carpaneto architekten, fatkoehl architekten, BARarchitekten. View into the public courtyard, Spreefeld, Berlin, Germany, 2014.

Photograph by Thomas Bruns.

SYDNEY SCHOOL 39

Figure 41. Vertical gardens extend the green space. Program/process/ project: die Zusammenarbeiter Gesellschaft von Architekten mbH; architecture: carpaneto architekten, fatkoehl architekten, BARarchitekten. Spreefeld, Berlin, Germany, 2013. Photograph by Thomas Bruns.

Figure 42. View into the vertical flat-garden. Program/process/project: die Zusammenarbeiter Gesellschaft von Architekten mbH; architecture: carpaneto architekten, fatkoehl architekten, BARarchitekten. Spreefeld, Berlin, Germany, 2013.

Photograph by Ute Zscharnt.

Figure 43. Programmatic mix. Program/process/project: die Zusammenarbeiter Gesellschaft von Architekten mbH; architecture: carpaneto architekten, fatkoehl architekten, BARarchitekten. Spreefeld, Berlin, Germany, 2014.

Figure 44. Activating the ground floor: Spaces for commercial use. Program/process/project: die Zusammenarbeiter Gesellschaft von Architekten mbH; architecture: carpaneto architekten, fatkoehl architekten, BARarchitekten. Spreefeld, Berlin, Germany, 2014.

New Propositions, Questioning Cost-Per-Square-Metre and Generosity 40 13 URBANGARDEN 10 youth club 11 laundry 12 communal room 13 courtyard 9 option space GROUND FLOOR RIVER COMMUNAL SPACE OPTION SPACE WORKING AREA STUDIOS, WORKSHOPS flexibility of use MEZZANINE B C A 9 D 10 PUB B A 9 10 B C A 9 10 Program, Process, Project: die Zusammenarbeiter Gesellschaft von Architekten mbH Architecture: carpaneto architekten fatkoehl architekten BARarchitekten 00 0M 01 02 03 04 05 06 DACH 47 % 25 % 4% 6 % 5 % STANDARD FLAT 54-290 m² total: 3580 m² CLUSTER UNIT H1: 705 m² H2: 580 m² H3: 620 m² total: 1.905 m² COMMUNAL SPACE guests fitness salon kids space storage laundry total: 350 m² COMMUNAL TERRACE 3 x 140 m² total: 420 m² OPTION SPACE 3x 128 m² total: 384 m² TOTAL: 7.620 m² PROGRAM INTERIOR 13 % COMMERCIAL UNIT 44-273 m² total: 980 m² HOUSE 3 carpaneto architekten BARarchitekten fatkoehl architekten HOUSE 1 HOUSE 2 Program, Process, Project: die Zusammenarbeiter Gesellschaft von Architekten mbH Architecture: carpaneto architekten fatkoehl architekten BARarchitekten URBANGARDEN 10 youth club 11 laundry 12 communal room 13 courtyard 9 option space GROUND FLOOR RIVER COMMUNAL SPACE OPTION SPACE WORKING AREA STUDIOS, WORKSHOPS flexibility of use MEZZANINE B C A 9 D 10 P B A 9 10 B C A 9 10 Program, Process, Project: die Zusammenarbeiter Gesellschaft von Architekten mbH fatkoehl architekten BARarchitekten

In addition, we o ered so-called optional spaces—the yellow spaces I showed. We took them out of the surface of this building, which is a passive house. So, we ended with the passive house on the ceiling here to allow the amateurs to build their own space. They were very clever. They said, we are not amateurs, we respect your design, we will try to find a very simple solution that is much cheaper. So, they built a workshop to build it. This workshop was used to build the furniture. Now it’s a public workshop where you can go and do projects. You know how precious space in cities is, so these spaces are really crucial. There are three of them. This is the one for food and for meetings, for discussions (fig. 46). It’s used all the time right now, especially for discussions about the future of the city. It has a non-industrial kitchen that everyone can use as well as a professional kitchen behind it that can also be used for events. There is no single space that only has one use. This space could also be changed to a double floor space for living, since the heights are within the regulations for residential use. You can see how both the interior and exterior spaces are used intensively, usually for projects that are curated, so to speak, as an o er to the city. What I like is the so-called boat house, where the GDR used to keep their police boats. Now, it can’t be removed—it’s a bunker, it has very thick concrete slabs. The inhabitants immediately took one of the bays for their own boat, but two of the other bays are now spaces for parties. That’s a very interesting way of taking it over.

This project is slightly di erent from what Andreas described before. While we were building it, there were always new people coming in, so we o ered these 46 versions of typologies (fig. 47). Because the process involved new people coming in, we had to o er a catalogue of possibilities of what people could a ord and what was possible, and then we had to puzzle to make sure that not a square metre was left unused at the end.

It has been a very process-driven project. We built models for the people to start designing the individual flats within the modular system of the project (fig. 48). This was also interesting as a collective work by the architects with whom I worked on one type of house. All three houses are di erent in the way they are put together. We also had these wild cards, where we didn’t tell the others what we liked and what we preferred and what we did slightly di erently.

As I said before, this allowed both individuality and collectivity. The collectivity is the rawest version of a flat that you could take when you have very, little money. But then you start to adapt it and you make the same space become what it should become for you. Because you have already been provided with a strong spatial condition, you don’t need too much to make it into something else. Perhaps sometimes you need a cat, I don’t know ...6

SYDNEY SCHOOL 41

Figure 45. Public space including the kindergarten. Program/process/ project: die Zusammenarbeiter Gesellschaft von Architekten mbH; architecture: carpaneto architekten, fatkoehl architekten, BARarchitekten. Spreefeld, Berlin, Germany, 2014. Photograph by Thomas Bruns.

6 Slide shows interior photograph of an apartment.

Zusammenarbeiter Gesellschaft von Architekten mbH; architecture: carpaneto architekten, fatkoehl architekten, BARarchitekten. Spreefeld, Berlin, Germany, 2014. Photograph by Andrea Kroth.

Program/process/project: die Zusammenarbeiter Gesellschaft von Architekten mbH; architecture: carpaneto architekten, fatkoehl architekten, BARarchitekten. Spreefeld, Berlin, Germany, 2014.

New Propositions, Questioning Cost-Per-Square-Metre and Generosity 42

Figure 46. Extra space for multiple use. Program/process/project: die

TYPOLOGICAL PUZZLE EAST-SOUTH-WEST 1-side exposure CORNER TYPE MIDDLE TYPE HEAD TYPE 2-side exposure 3-side exposure A B EAST-NORTH-WEST EXAMPLE Combination in the SHORT-Floor EXAMPLE Combination in the LONG-Floor 130 120 100 85 50 185m² 100m² 85m² 105m² 130m² 150m² 120m² 145m² 165m² 200m² 65m² 80m² 55m² 50m² 50m² 45m² 45m² 160m² 125m² 100m² 75m² 140m² 160m² 180m² 120m² 130m² 170m² 25m² 100m² 120m² 165m² 185m² 210m² 145m² 45m² 50m² 2 x 45m² 85m² 110m² 35m² 90m² 65m² 80m² 65m² 85m² 100m² 1 2 A B A B A B 45 45 2 1 Program, Process, Project: die Zusammenarbeiter Gesellschaft von Architekten mbH Architecture: carpaneto architekten fatkoehl architekten BARarchitekten TYPOLOGICAL PUZZLE EAST-SOUTH-WEST 1-side exposure CORNER TYPE MIDDLE TYPE HEAD TYPE 2-side exposure 3-side exposure A B EAST-NORTH-WEST EXAMPLE Combination in the SHORT-Floor EXAMPLE Combination in the LONG-Floor 130 120 100 85 50 185m² 100m² 85m² 105m² 130m² 150m² 120m² 145m² 165m² 200m² 65m² 80m² 55m² 50m² 50m² 45m² 45m² 160m² 125m² 100m² 75m² 140m² 160m² 180m² 120m² 130m² 170m² 25m² 100m² 120m² 165m² 185m² 210m² 145m² 45m² 50m² 2 x 45m² 85m² 110m² 35m² 90m² 65m² 80m² 65m² 85m² 100m² 1 2 A B A B A B 45 45 2 1 Program, Process, Project: die Zusammenarbeiter Gesellschaft von Architekten mbH Architecture: carpaneto architekten fatkoehl architekten BARarchitekten

Figure 47. Catalogue of floor plans.

Modular

for maximum spatial flexibility. Program/process/project: die Zusammenarbeiter Gesellschaft von Architekten mbH; architecture: carpaneto architekten, fatkoehl architekten, BARarchitekten. Spreefeld, Berlin, Germany, 2014. Photograph by BARarchitekten.

mbH; architecture: carpaneto architekten, fatkoehl architekten, BARarchitekten. Spreefeld, Berlin, Germany, 2014.

SYDNEY SCHOOL 43 5 mini-kitchen 6 bathroom 7 bed 8 private terrace 1ST FLOOR 2ND FLOOR CLUSTER UNIT COMMUNAL SPACES SINGLE UNIT 1ST FLOOR 2ND FLOOR 1 2 3 4 1 living room 2 kitchen 3 bathroom 4 communal terrace 7 5 6 Program, Process, Project: die Zusammenarbeiter Gesellschaft von Architekten mbH Architecture: carpaneto architekten fatkoehl architekten BARarchitekten 5 mini-kitchen 6 bathroom 7 bed 8 private terrace 1ST FLOOR 2ND FLOOR CLUSTER UNIT COMMUNAL SPACES SINGLE UNIT 1ST FLOOR 2ND FLOOR 1 2 3 4 1 living room 2 kitchen 3 bathroom 4 communal terrace 7 5 6 Program, Process, Project: die Zusammenarbeiter Gesellschaft von Architekten mbH Architecture: carpaneto architekten fatkoehl architekten BARarchitekten

Figure 48.

principles

Figure 49. Cluster Apartment with the yellow common space. Program/process/project: die Zusammenarbeiter Gesellschaft von Architekten

Liegenschaftspolitik: Erbbaurecht in Berlin, Dokumentation der Expertenwerkstatt. [Translation: Documentation workshop with experts on heritable building right or leasehold business model in Berlin]. [Right:] Runder Tisch

Liegenschaftspolitik: Dokumentation Werkstatt Konzeptverfahren. {Translation: Documentation Workshop on a new model to give away land for the most sustainable and affordable projects].

For me, the cluster flats are a very interesting model of future living (fig. 49). You can see the yellow spaces—this is where you share the kitchen, and you share a living room right at the river. So, the best space is at the river. The other spaces also have a small kitchen and a small bathroom. These were quite old people, so they wanted to have a small version of a retreat. So, we understood this as a street.7 In other spaces, people had less money, so they would share 80 square metres. There were 20 people. If they have a 20 square metre room, they pay for 24, but they use 100. This is another interesting idea for how to make space accessible to more people.

Now, you asked me about the obstacles, about when these things stop. Here in Berlin, they stopped quite dramatically. Here you see a chart of one of the centre areas showing the increase in the price of land. In 2012, the price of land was still quite low, but it changed dramatically through the crisis—through the bank crash in the States—and then through economic growth in Berlin. It also stopped the Baugruppen. The city was not capable of making this model part of their policies for city development. So, you find very little Baugruppen in Berlin, but other cities took over this model. This is the main reason—as you can see, there has been a 764% increase in the price of land. You can imagine the consequence of this for rent.

Right now we are working on new modes. On the left side—the pink—is where you no longer buy land but lease it at a low cost, even if the price of the land is very expensive (fig. 50). There’s a moratorium on all land in Berlin—in future, you can only lease land, which is the first clever move. The next step—in which I am also very engaged—is to decide who gets any land that is available. This is the so-called Konzeptverfahren, which means that now you have to o er a very strong concept, which is socially oriented and has all the components I was talking about in the beginning. If you o er this, you get the land for a certain period of time. This is the beach again at the Spreefeld. I hope that this will allow us to make this kind of city again, to make the kinds of projects I have shown.

Thank you very much.

New Propositions, Questioning Cost-Per-Square-Metre and Generosity 44

Figure 50. Publications in collaboration with the Senatsverwaltung für Stadtentwicklung und Wohnen in Berlin. [Left:] Runder Tisch

7 Slide shows an axonometric drawing of the cluster flat with a central corridor connecting the communal spaces.

HF

Thank you very much for that. And thank you very much, Anne, Jean-Philippe and of course, Andreas for these very inspiring presentations. There are so many interesting themes to pick up on in terms of how we think about alternative organisations for housing development, and in relation to what is happening in the transformation in the cities. I’m sure there are a lot of questions and comments from the audience and from the people online. We don’t have much time left, but I think it would be nice to have a brief discussion. I thought I could begin and then we can open up for other questions and comments. It could be interesting—and all three presentations here have touched on it—to think about the main title of this entire symposium, which is about living in the city. The projects we’ve seen today are not part of a traditional master plan—it’s very obvious. Rather, they happen in these very specific sites, in relation to existing structures or as the densification of historical plans, or even in relation to historical versions of, for example the IBA. The common denominator here is alternative strategies of development. They exist in very small land plots—the kind of cavities of the city that the master plan didn’t define or forgot or didn’t reach. For example, I find the mapping of these situationes urbaines capables incredibly relevant for this. There is a similar approach in Florian’s identification of the desolate sites in Berlin.