8 minute read

BACK FROM THE BRINK

Saving Atlantic Salmon from Extinction, One Parr at a Time

by Tom Keer

Low gray clouds that spurt rain have different effects on fly anglers. When a low-pressure system rolls down the river and the first drops fall, some anglers make a beeline for pancakes and coffee at the nearest greasy spoon. As the rain falls harder, others make “one last cast” after another until they can take no more. Then they’ll sit in their trucks and wait out the downfall. When the rain stops they’ll head back to the river for more. The hardiest of them simply pull rain gear from the back pocket of their vests and keep fishing. The funny thing is that the latter group might have done a rain dance in the first place: If they’re Atlantic salmon anglers, they’ll know that the best fishing is yet to come.

Steady rain brings cooler temperatures and richly oxygenated water to a salmon river and a rise in levels that lights everything up. The higher, faster water enables fish returning from the sea to leave

low-water pools and move upriver to spawn. Atlantic salmon can snake their way through boney riffles until they hold in the quiet water. Some are positioned behind boulders, others in lies—and when more rain falls they’ll continue upstream again.

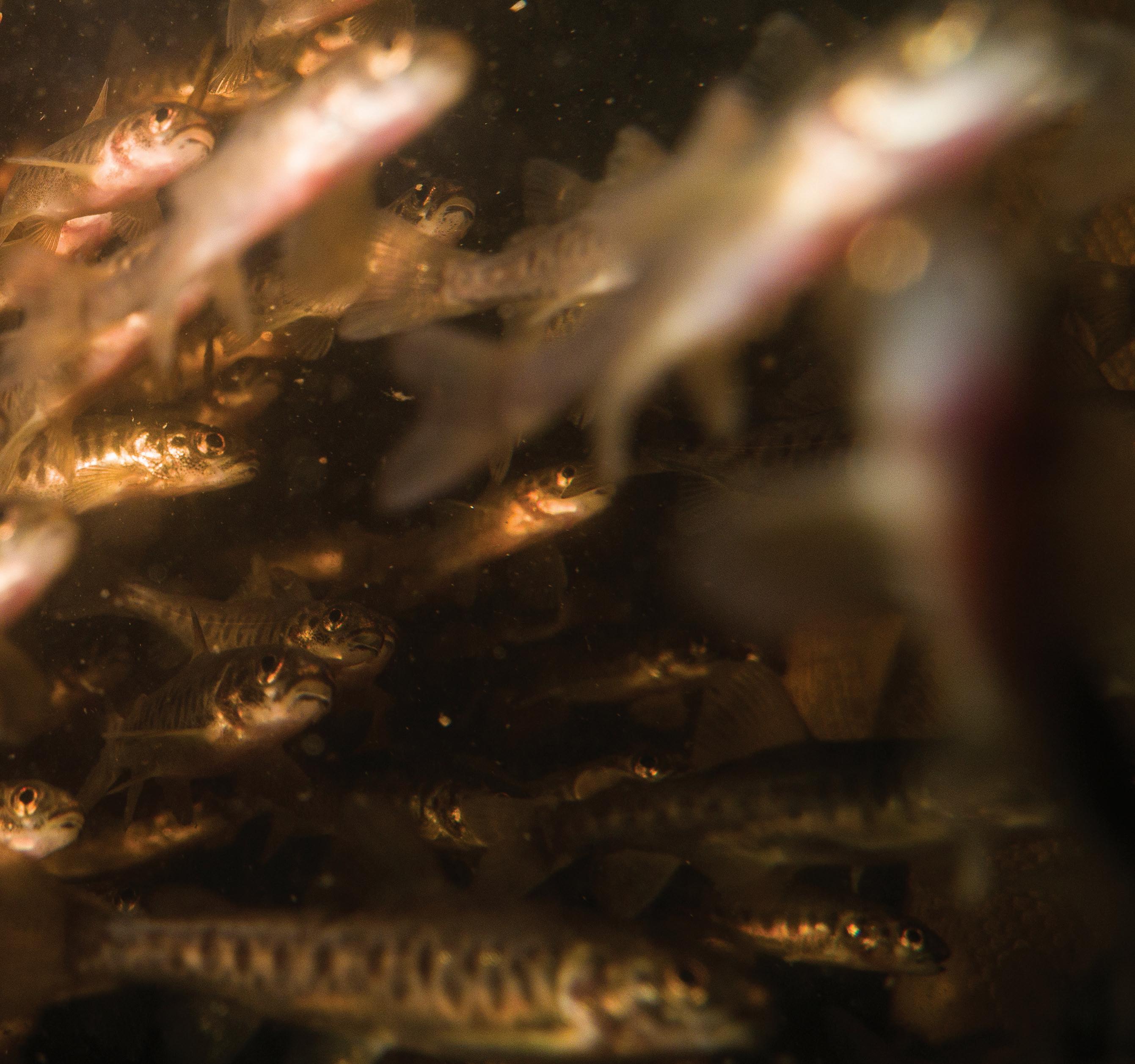

The odyssey of the Atlantic salmon, epic in proportion, has intrigued and inspired generations of anglers, biologists, and conservationists. Unlike Pacific salmon, Atlantic salmon don’t die following a spawn. Instead, their fertilized eggs laid in a redd grow to become first alevin and then parr. When old enough, parr undergo a metamorphosis called smoltification, during which these fish born in the sweet water become tolerant of the salt and drop out of the rivers to begin their life at sea. Smolt mature into Atlantic salmon and complete a 3,000-mile swim from coastal New England to the west coast of Greenland. After one, two, or even three years in the brine they

return to spawn in the rivers in which they were born.

Their homecoming is a joyous occasion for everyone. Camp owners welcome fishermen from far-flung locales while local fly anglers cast and mend. Guides coach anglers through backing-burning runs and leaps. Townsfolk line riverbanks, turning Atlantic salmon fishing into something of a quiet spectator sport. Fish tales of salmon lost and caught are the talk over coffee, bourbon, or Scotch.

No one fishes for wild Atlantic salmon in America: Their stocks are so imperiled that Atlantic salmon are classified as an endangered species. That’s terrible news, because Atlantic salmon are unlike brown trout imported from Germany. They are unlike gaudy ring-necked pheasant imported from China. Like the brook trout, ruffed grouse, American woodcock, and white-tailed deer, Atlantic salmon are one of us. A century ago they were as common as a summer sunburn; now they are on the brink of extinction.

A century ago, and before refrigeration, more than 300,000 Atlantic salmon arrived in New England rivers each summer and were easy to net. Atlantic salmon were so American and so plentiful that they were standard Fourth of July fare, served up with peas, a vegetable ripe enough to harvest in late June and early July. Since then overharvesting, dam construction, and the silting and polluting of rivers have combined to reduce domestic Atlantic salmon numbers to an all-time low. Today fresh salmon for Independence Day is no more; now we slum it with hamburgers and hot dogs at our Fourth of July picnics.

A little bit of history has been lost as well. No longer is the first Atlantic salmon caught in Maine’s Penobscot River sent to the President of the United States; that tradition ceased 25 years ago when the fish was classified as endangered. The last President to receive a Mainecaught Atlantic salmon was George H. W. Bush in 1992. Add to that the fact that most Atlantic salmon restoration programs were shuttered as failures, and our native fish seems doomed.

Some would be content to allow the wild American Atlantic salmon to become extinct like the heath hen before it—but not the Downeast Salmon Federation (DSF). In 2012 on Maine’s East Machias River, the DSF launched the Peter Gray Parr Project (www.wildatlanticsalmon.org), based on the successful salmon restoration methods employed by legendary British fisheries biologist Peter Gray on England’s River Tyne. Gray spent 27 years managing the famous Kielder Hatchery and in his tenure developed a unique and successful way to raise salmon as salmon. First Gray located his hatchery adjacent to the river where salmon spawned. Next he diverted river water from the Tyne to flow into the hatchery so fish were reared in water identical to that in which they would live.

Then he created the substrate box that closely replicates a wild salmon redd for egg maturation. He painted rearing tanks black to darken the parr and condition the small fish to low light conditions so that when they were released into the wild the parr would be naturally wary. Finally, as the fish developed, Gray increased tank water flows to turn fish into “little athletes” capable of life in the wild. The strong fish were stocked in the fall when the water temperatures were cold so that their metabolic rates lowered and they did not look to feed (and fall prey to hungry cormorants and herons).

In contrast to Gray’s efforts, United States Atlantic salmon programs—almost all of which are now shuttered—raised their salmon like trout: They were reared in inland hatcheries with a limited number of broodstock. No conditioning was done. The fish lived in water different from their natural environment. They were stocked in the spring. Some fish died shortly after stocking, while others became meals for predatory fish and birds.

Peter Gray’s program has been hailed as one of the most impressive wild Atlantic salmon restoration efforts in the 170-year history of Atlantic salmon conservation. His results were staggering: Annual salmon returns increased on the River Tyne from 724 to nearly 10,000 adults. A recreational fishery for these wonderful gamefish has now been open for years.

The DSF has been building toward success for the past nine years. In 2019, when consistent spring rains brought the East Machias River to optimal water levels, the smolttrapping operation yielded 220 smolt departing the river for the sea—220 captured fish that mark a threeyear trend of the highest number of exiting smolt, the best trend line from any river in the past decade. Of those smolt, 20 were wild or had been stocked by DSF as unmarked fry from their Peter Gray incubators, and

200 were stocked as parr by the DSF. Not every smolt is caught, so the estimated total number of departing fish marks the second highest number since the program began. The next few years of the program are critically important, particularly because returning adults will begin to arrive.

DSF founding CEO Dwayne Shaw offers up even more good news: “One of our most important metrics is the number of redds in the river,” he says. “Those redds, the nesting areas made by returning fish, are the first step of the breeding process. This year we counted 60 redds, the highest number we’ve seen since we launched the Peter Gray Parr Project. It’s indicative of at least 48 returning adult fish. To put it in perspective, that is the highest number of returning Atlantic salmon documented since the 1970s. In effect we have reversed a 50-year decline.”

Removing a species from the Endangered Species List is a numbers game. The more eggs secured results in more parr raised and stocked and more smolt that head to sea. Atlantic salmon return over a three-year period, so the next decade will be one of intense activity and study wrapped in a veil of hope.

Financial support for the Peter Gray Parr Project is focused on increasing parr production to about 400,000 per year for the next five years, on improving tributary watersheds crucial to stocking success, and on other DSF habitat management and protection projects. Support has come from concerned anglers as well as numerous companies, including fly rod manufacturer Thomas & Thomas, now celebrating its 50th anniversary. Says T&T’s John Carpenter, “Few fish have the iconic presence in fly fishing that the Atlantic salmon enjoys, yet the challenges faced by the species are also unique—and enormous. Thomas & Thomas is thrilled to support the conservation efforts of the Peter Gray Parr Project, with the goal of creating or expanding self-sustaining runs of wild salmon for generations to come. Together we hope to ensure that our children and grandchildren have the opportunity to live in a world with these magnificent fish.”

Dwayne Shaw notes that the project has faced down skeptics from the very beginning. “They weren’t sold on the process or the viability of the project,” he says, “but since we had 60 redds, many state and federal agencies are working with us to increase our capacities. We’re creating higher-quality habitat and beginning work on other area rivers. What once was viewed as experimental now shows scientifically verifiable results. We couldn’t be more excited about the renewed interest in saving Atlantic salmon.”

The ultimate goal of the DSF’s Peter Gray Parr Project is to return Atlantic salmon populations to healthy numbers. Perhaps then rivers can reopen for recreational fishing. Toward that end, the DSF is doing the heavy lifting—but they can’t do it alone: Wild Atlantic salmon need our help. One day maybe we or our kids will hook one of these glorious fish, and then we’ll see what all the commotion is about. To raise and stock a single parr costs only a dollar. To learn more about the Peter Gray Parr Project or to make a donation, visit www.wildatlanticsalmon.org.