3 minute read

Local Cuisine in the 1800s

By Drew Desmond | Secretary, Prescott Western Heritage Foundation

When this area of Yavapai County was first being settled by Americans, food was expensive and difficult to procure. The Walker Party’s first winter of 1864 was particularly harsh. They came to the area in search of gold, and they indeed found it, but gold is worthless when there’s no food to buy. Such was the case in Prescott that dreary and desperate winter and the only people who could save the small mining camp from starvation were the Miller brothers, of Miller Valley fame. They were the teamsters of the Party, and the only ones equipped to go to California for food. Navigating a harsh trek, they persevered through dangerous Indian country and were able to complete the trip, providing food for a very grateful Prescott. From then on, they would always be considered heroes.

After that close call, more freighters were able to make the trip. Restaurants began to open, but were not specific in advertising their menus. Instead, they only promised “the best the market affords, cooked, and dished up in good style.” This often meant hunted game. When an animal was procured, steaks were served first with successive meals ultimately deteriorating to “mystery meat” stews or meatloaves.

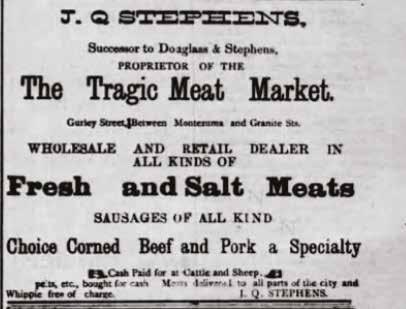

Prescott was also soon stocked by area homesteader farms and ranches, and by 1869 butcher shops were able to advertise the constant availability of beef, pork and “other meats” which usually meant wild venison, turkey and duck. Although meat could be purchased easily, and generally sold for what we pay today, the one exception was bacon. It was a delicacy at $15 a pound in today’s money. However, the price of common kitchen staples was shockingly expensive in the 1860s. Translating prices into today’s dollars: butter would cost $25 per pound; five pounds of flour, $22; and a dozen eggs, $40! Coffee, tea and sugar cost the equivalent of $15 a pound. In 1869 the newspaper reported that “milk was scarce owing to the fact that many of our cows have gone with the Apaches, and have not yet come home.”

Locally grown fruits and vegetables were a bargain when the crop came in. Otherwise, off-season availability, particularly around Christmas, was also expensive. Canning was not only popular, but for many, it was a must.

The land itself offered a bounty to pioneers, particularly in mid to late summer. Some of the edible fruits that still grow wild in Yavapai County include raspberries, strawberries, blackberries, elderberries, serviceberries, black cherries, manzanita, hollygrapes, and Arizona grapes. Many of these were preserved into jams and jellies.

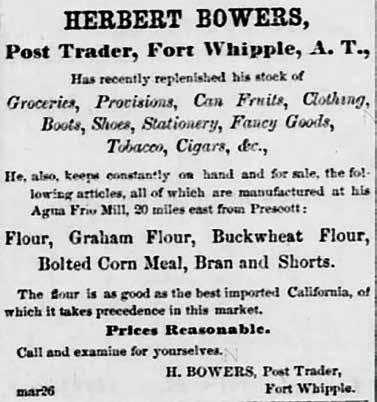

Newspaper images courtesy of Drew Desmond

The wild vegetables of Yavapai County include potatoes, onions, and spotted beans. Some seeds are edible and nutritious, most notably pinyon pine.

As the trade and mail routes became more secure during the Indian conflicts, food variety increased and prices decreased. There was now enough of a supply for Prescott businesses to sell wholesale. In 1871, Montezuma St. saw the opening of a French restaurant. The price of flour remained stubborn, however, as many area farmers grew fodder for horses instead of grain. The US Army/Cavalry surrounding the area were big consumers and offered cold, hard cash for livestock feed.

In mid-July, 1875, the Antelope restaurant had an industrial ice cream maker freighted in, and enjoyed a monopoly on the frozen confection for three years. They charged a high price, however, as a simple dish for dessert was the same price as the entire meal before it!

One man, Jules Baumann, had an oyster parlor in downtown Prescott and started selling ice cream in March of 1886. He also kept his establishment open in the wee hours of the morning after dances and other activities, offering a place to go after the main festivity. Late night “oysters and ice cream” became surprisingly popular. So much so that Baumann, facing a mountain of empty oyster shells, decided to boil them into a brine and used that to produce oyster flavored ice cream! Initially, at least, the newspaper reported that it “was very popular.”

Oysters were not the only seafood available. Grocers advertised codfish, salmon, mackerel, and even lobster, although these must have been canned.

Finally, when the railroad made it into Prescott on January 1,1887, all commerce changed, including the food available. Now anything that could be shipped by rail was; including fresh seafood packed on ice. The door to the world sprang open and all varieties of food became available at far more reasonable prices.