sight & sound

Founder / Jonathan Touche

Editor / Jorge Mendizabal

Managing Editor / Evan Pricco

Associate Editor / Erin Dyer

Art Director / Jeremy Ortega

Curator / Greg Escalante

Creative Consultant / Suzanne Williams

Creative Director / Hybrid Design

Senior Photographer / CR Stecyk II

Editorial Assistant / Lauren Riggins

Production Assistant / Trenton Temple / Dan Whitley / Joshua Descateau

Digital Media / Katie Zuppann

Contributing Writers / Jim Hemphill / Mark Kermode / Cris O’Falt / Sarah Tai Black / Shaylee Patterson / Paige

Presley

Contributing Photographers / Brooke Boatman / Robin Blackshear / Meranda Garcia / Eduardo Martinez / Tyler Schultz / Krisjan Carter / Hannah Ryan

Contributing Directors / Wes Anderson / Berry Jenkins / Daniel Kwan / Bong Joon-Ho / Quentin Tarantino

Advertising Director / William Haugh

Advertising Sales / Eben Sterling

President / Gwynned Vitello

Vice President / Eric Swenson

Publisher / Edward H. Riggins

CFO / Jeff Rafnson

Accounting / Marcy Boatman

Counsel / Krisjan Carter / Faith Beall / Jon Godines / Melody Peppard / Jacob Sazon / Mariah Maldanado

Sight & Sound is published by Momentum, Inc. (361) 555-5555

Email us at editor@sightandsound.com www.sightandsound.com

@sightandsound

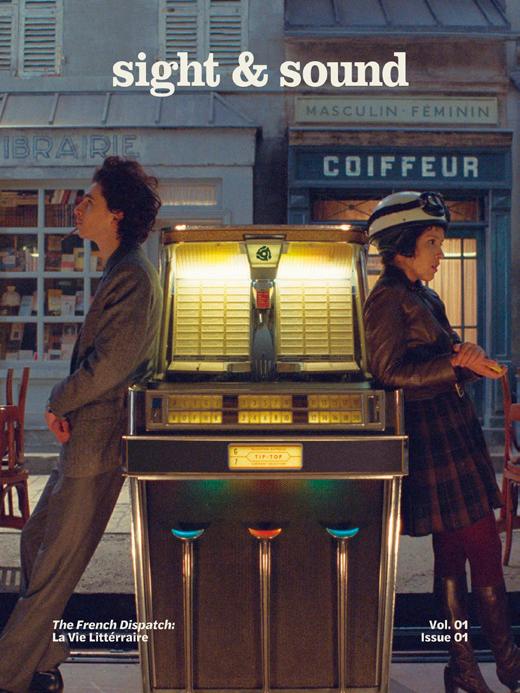

The cover of Issue 01 is from the first feature, "La Vie Litteraire: The French Dispatch," written by senior contributor Jim Hemphill. The feature dives into Wes Anderson's most recent work alongside Robert Yeoman in this whimsical exploration of literary life.

Film has long been a method of communicating ideas, beliefs, and systems to audiences around the world. But the question has long been posed as to just how much of fil m should be left up to the subjective interpretation fo audiences and how much should be objective and concrete, structured tonality. How does a film maker truly set the tone of messaging without providing a concrete explanation of the underlying message?

The two greatest methods, particulary discussed in this issue, are likely the most obvious to filmmakers. But these same two methods are often unrecognized indicators to audiences. Doing their job silently. Lighting and colorgrading are two methods in which filmmakers indicate the tonality of the film, guiding viewers to

understand the tone of film without giving the audience an on-the-nose explanation of the message.

As film continues to grow and evolve, these aspects of the craft will only, assumingly, grow as well. Tone creates a sense of presence for the viewer, and draws them in to the action on screen. A compelling story is at the heart of any engaging movie, and when you become invested as an audience member in the story, the director and crew have done their jobs properly. Tone is powerful, and it is ultimately the vehicle that carries the audience on their cinematic journey through your story. Tone can change from scene to scene, so ensure each moment is carefully crafted to achieve what you want it to.

(in focus)

“In

many ways an homage to the inimitable grace and talent of its star Michelle Yeoh, the film takes gleeful joy in the experiential potential of limitless cinematic shape-shifting.”

“Real life adulting is the ultimate foe to be vanquished in this deliriously haywire fantasy, a cinematic tab of acid buried in a metaphysical fable of chaos.”

“Never have I seen a film with such scope and ambition succeed so imarveliously... The above rave notwithstanding, no film is perfector so I’ve been told... Having authored the film to end all films, what the hell will Daniels follow it with in the end?”

“Its a wholly original movie at a time when originality is in short supply.”

JORDAN PEELE TALKS ‘NOPE’ AND WHY HE KNEW KEKE PALMER WAS PERFECT FOR ROLE

written by KARLA RODRIGUEZ

Nope is an original story about UFOs, a tale as old as time, but it has never been done quite in this way before. The film follows two siblings, OJ Haywood (Daniel Kaluuya) and Emerald Haywood (Keke Palmer), who are left in charge of their father’s ranch after his mysterious passing. They soon realize that their father’s death was caused by random items falling from the sky that dropped down from an unidentified flying object.

Down on their luck and struggling to keep the ranch afloat, the brother and sister aim to go viral by capturing the phenomenon on video. Sight & Sound caught up with the director ahead of the movie’s release for a chat about Nope, casting Keke Palmer, why he thinks people love his movies, and what his thoughts are on being called one of the greatest directors of all time.

I have already been asked if Nope is better than Get Out so I’m sure you’re already getting that question. As a director, do you feel pressure to top your previous work or do you treat them all as separate entities?

You know, I think you have to treat them as separate entities. Because I think even if people think they want you to do something similar, they really want you to break out of that mold and so that’s always the challenge I put on myself. How do I keep some essence of what people like about my work but give him something completely different and that’s how we got Nope.

I know casting Daniel felt like an easy choice here, he’s great as OJ, but I think the star of the movie is really Keke. She brought so much humor and joy to this otherwise really scary movie. Did you know right off the bat that she was going to be Emerald?

Yes, I did know off the bat that she was going to be Emerald. In fact, as soon as the character came to me it was Keke. We met early on and I just got a sense of her and got a sense of what she could bring to the role and I basically wrote it for her. I wrote it for her and Daniel and she is just everything you want her to be. She really is that wonderful and that talented.

People are already talking about needing to see this movie once or twice in theaters. What do you think it is about your movies that drives people to the theaters, even though it’s an original and it’s not a reboot or something that people already know?

I think people like to watch people watch my movies. So I think after they have seen it, you like to go and feel that feeling of the audience’s reactions again and there’s also layers baked into it and people can feel that. I think sometimes people like to watch the movie intently and really try to treasure hunt and figure everything out. Sometimes you don’t want to think too hard, you want to walk into a movie, you want to be taken care of, you want to be taken to a different place, you want to be put back in your car, and I think Nope can do either one of those for you.

There’s a lot of commentary about Hollywood within the movie, about animals in film, child stars, and the mention of the Purple People Eater. How much of your love for pop culture and film goes into the films that you create?

I basically try to take absurd premise, scary, comedic, however you view it, I’m trying to make it feel real, I’m trying to ground it because that is how you can help someone relate to it, right? Feel the fear or feel and understand the humor. So I have been putting more and more sort of things from my reference base that just kind of ground me in the world and make it feel real. And there’s a lot of that. For instance, the movie Kid Sheriff from the ’90s I reference in the film, which is one of my favorites.

You’re already in the conversation as being one of the greatest actors—I mean, directors— of all time, not just horror directors, but of all time. How does that feel for you? Do you feel pressure or were you prepared to become that?

You almost said I was one of the greatest actors of all time. And then you stopped yourself, appropriately, you backed it up and said, “Beep, beep, beep!” [Laughs.] We can’t let that sentence be out there, that Jordan Peele is one of the greatest actors!

story by Jim Hemphill

La Vie

story by Jim Hemphill

La Vie

The story begins with the death of the fictional magazine’s editor, Arthur Howitzer Jr. (Bill Murray), whose passing inspires recollections of highlights from Dispatch history. These include the tale of an imprisoned, brilliant, and possibly insane painter (Benicio Del Toro) whose muse is one of his prison guards (Léa Seydoux); a lively account of a student revolt in Paris; and a kidnapping adventure involving the French police and their renowned institutional chef.

The array of stories enabled Yeoman to employ a variety of stylistic techniques — including moving between color and blackand-white and transitioning from one aspect ratio to another — while retaining the symmetrical, deep-focus compositions Anderson has always favored.

The cinematographer’s prep for The French Dispatch began the way it usually does with Anderson: the director sent him the script, a list of the actors who would star, and a detailed animatic. “It’s really beneficial to me to know which actors are playing which parts,” says Yeoman. “Wes’ animatic is kind of a cartoon version of the film, and it’s pretty intricate. He does all the voices, and you get an idea about the locations, the camera moves, and so on. Once I have that, we have Zoom conversations and exchange emails about the look and ideas and references, which gets the ball rolling.”

Perhaps not surprisingly, many of the references for The French Dispatch were from French cinema, specifically the French New Wave, which has held special meaning for Anderson and Yeoman throughout their creative partnership. Raoul Coutard’s cinematography in films by Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut was particularly relevant, says Yeoman. The film’s success is largely correlated to the intricacies in art.

“[On every movie,] Wes sets up a library of DVDs and Blurays that cast and crew can check out, and we watch a lot of them and discuss them,” he says. “After a while, it enters your subconscious. At one point Wes and I were talking about lighting a particular scene, and I said, ‘Vivre Sa Vie,’ and he replied, ‘Yes, exactly.’”

Although The French Dispatch takes inspiration from many notable films (including Henri-Georges Clouzot’s Diabolique and Louis Malle’s The Fire Within), its visual language will be familiar to Anderson’s fans. Vincent Scotet, who served as 1st AC on the project, says that upon entering a set, he immediately located the dead-center point in the room, “and if we were in doubt about where that was, we got out the measuring tape.”

Once the center was established, Yeoman and his crew went about executing Anderson’s animatics, which called for actions that often ran up against the physical limitations of actors and locations. “The challenge we have in a lot of the animatics is that the actors and camera move extremely fast in them,” says Yeoman. “In real life, that’s

not easy to do, especially when the actors are going up stairs, for example. But [key grip and Steadicam operator] Sanjay [Sami] was a rugby player, so he’s pretty fast, and he’s adept at pushing the dolly very quickly and coming to a very quick stop.”

Sami, who has worked with Yeoman and Anderson since The Darjeeling Limited (2007), is often tasked with creating unusual rigs to realize Anderson’s ambitions, as the director has an aversion to many modern filmmaking tools. “Wes likes to do things old-school, so we all have to embrace the lack of some of the technical gear we might ordinarily use — like camera cars and Technocranes, for instance,” Yeoman says. “The last time we used a Technocrane was on The Royal Tenenbaums, for the big shot

following Owen Wilson’s car accident. We rely on Sanjay to come up with more homemade approaches to doing things on their own.”

Yeoman and his crew agree that, often, these “more analog” methods work out better, especially for complicated shots that involve combinations of whip-pans and dolly moves in which the camera must interact with the actors in a meticulously choreographed dance. “We have to be able to change direction on the track very quickly and be as precise as Wes wants to be down to the millimeter,” Sami says, “because if you’re off by a millimeter, [the frame] isn’t centered anymore when you hit your mark. You need to hit your mark and then move back 90 degrees on that axis. There are very hard stops and very

fast pullbacks, and the 90-degree angle changes happen very quickly.”

To help achieve those kinds of camera moves with the desired elegance, Sami designed a series of switch tracks in-spired by his children’s toy-train set. “The switch tracks allow us to very quickly change direction with the precision Wes wants,” he explains. “I love rising to the challenge of figuring out the physics of creating the shot that’s in Wes’ head.” The other component to those tricky moves is Yeoman’s operating. “I usually use a geared head, but on those shots, I use a fluid head and twist myself into a pretzel,” the cinematographer explains. “I put my feet where the landing position should be, so at the beginning of the shot I’m often very uncomfortable. Then, as I swing around, I come to a position where I feel I’m balanced, and that’s kind of how I do it. The more I have to do them, the more nervous I get, because if I blow a take with a group of great actors, I feel terrible about it.”

Sami notes that “it’s very, very rare that we do a take again because Bob missed it — and it’s not as simple as just twisting and untwisting, because there are often multiple swish-pans in the same shot. Plus, I’m tracking at the same time, and we’re doing really fast dolly moves with really hard stops again and again. It’s a 270-degree swish pan with four stops on the way while the dolly is moving!”

The deep focus that’s characteristic of Anderson’s frames placed similarly great demands on Scotet. “Today it’s very fashionable to shoot wide open and have very narrow depth of field, but we do the opposite,” says Yeoman.

“Many times, Wes will have an actor very close to the camera and other actors in the background, and he’ll want everybody in focus. I’d say to Vincent, ‘Hey, what do I need to carry focus here?’ And he’d say, ‘You need a T8 to do that.’ So, we’d light to a T8.

“In this film, we had a long dolly shot with actors frozen in place, with some very close to camera and some very far,” Yeoman continues. “We shot that at T11, and it’s an interior. We brought in a lot of lights because we needed that depth of field to carry everybody in focus. Greg Fromentin, my gaffer, did an amazing job with that. We were shooting with a Cooke S4 25mm lens on an Arri ST at 200 ASA. To light the sequence, we needed six 18K HMIs and two 9K HMIs bounced into the ceiling, which was covered with white cloth. We put the lights behind the set walls.”

Adds Scotet, who was collaborating with Anderson and Yeoman for the first time, “I remember that day very well. We had an actor in the foreground who was 2 feet from the camera and one in the back who was 20 or 25 feet away. Working with Wes and Bob [involves] a different way of talking about focus and the choices you make in a shot. It’s often more about where I should set focus to play with the depth of field and carry as many actors as possible, instead of choosing one specific actor in the frame to be sharper than the others. Most of the time we’re using split focus, when the T-stop allows us to do so.”

Despite the rigorous technical requirements, Anderson’s sets tend to be very stripped-down. “We have the smallest on-set crew imaginable,” Yeoman says. “It’s a very differ-

ent way of working. Wes does not like an army of people around. He doesn’t like video village or anything like it; he tries to create an intimate atmosphere for the actors.

“I generally don’t bring a lot of lights onto the set,” he continues. “For example, on The Grand Budapest Hotel [AC March ’14], our hotel location had a giant skylight, and we just bounced a lot of HMIs through that, used a lot of practicals inside, and brought in one light for the actors. That was pretty much how we did the interiors. Wes doesn’t want to see a lot of lights and light stands; he’d rather keep the space as clean as possible.”

The director also prefers keeping company moves to a minimum, favoring locations that are within a golf cart’s ride from the production’s hotel. “There are fewer logistical problems because everything is close by,” Sami says, “and everyone gets the flavor of the place they’re working in [by staying in the area.] That’s less likely to happen on a backlot.”

Anderson’s old-school approach extends to shooting on film, and Yeoman says he appreciates the discipline the more traditional medium brings to a set. “In general, I think everyone pays attention and focuses more when you’re shooting film,” he notes. “When you shoot digitally, often you turn the camera on and just keep rolling, and the hair-and-makeup people go in between takes. With film, when you slap the slate, everyone’s attention is really there. The disadvantage is that we shoot [Kodak Vision3 200T] 5213, which is [ISO] 200!

We shot on that stock for all the color scenes, and we used Kodak 5222 [ISO 250] black-and-white stock for all the black-and-white material. When you shoot on [Arri] Alexa, of course, it’s [ISO] 800. So, we needed more light, particularly for nights and interiors, although we didn’t have to break our rule about ‘fewer lights and light stands’ that often on this picture — only occasionally. When I’m shooting film, I do go back to using my [light] meters much more than when I shoot digitally.”

But for Yeoman, the payoff is worth it. “There’s something magical about shooting film,” he says. “With digital, you can see on the monitor pretty much exactly what you’re going to get. With film, there’s a magic that happens from the moment we load the film to when it goes to the lab and someone else prints it. I certainly have a pretty good idea of what it’s going to look like, but there are often surprises — and generally good ones.”

Sami concurs, recalling that on Moonrise Kingdom [AC June ’12], which Yeoman shot on Super 16mm, “the dailies often surprised us. A lot of the takes that we presumed were going to be way too dark were actually really good.”

Yeoman adds, “Don’t get me wrong, I love what we can do with the Alexa and other digital cameras. At the same time, I think a lot of the magic of filmmaking has been lost since we entered the digital world, and that magical quality appeals to me.”

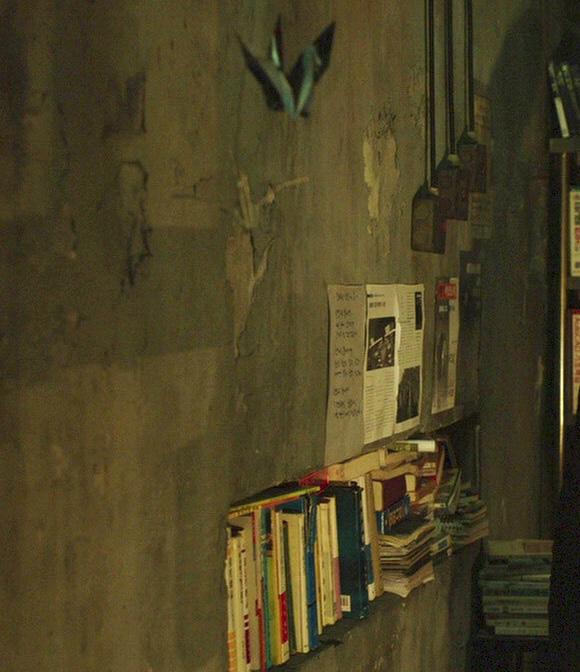

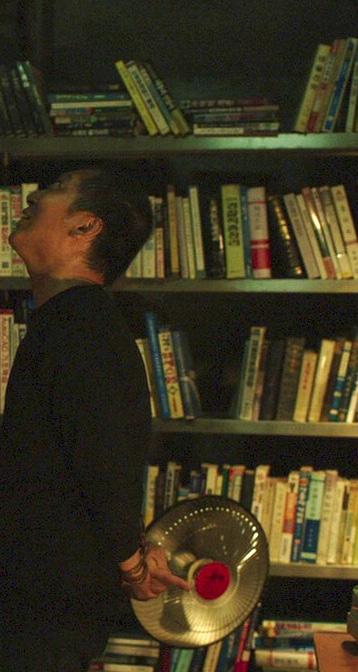

Described by its creator as “a comedy without clowns, a tragedy without villains”, Parasite is more Shakespearean than Hitchockian – a tale of two families from opposite ends of the socioeconomic spectrum, told with the trademark genre-fluidity that has seen Bong’s back catalogue slip seamlessly from murder mystery, via monster movie, to dystopian future-fantasy and beyond. We first meet the Kim family, headed by father Ki-taek (Song Kang-ho) and mother Chung-sook (Chang Hyae-jin), in their lowly semi-basement home, hunting for stray wifi coverage and leaving their windows open to benefit from bug-killing street fumigation. They have nothing but one another and a shared sense of hard-scrabble entrepreneurism. So when son Ki-woo (Choi Woo-shik) is faced with an unexpected opportunity to home-tutor a rich schoolgirl, he gets his gifted artist sister, Ki-jung (Park So-dam), to forge a college certificate, bluffing his way into the job and into the home of the Park family.

The use of colorgrading and lighting, paired with the strong visual language and facial expressions create a powerful sense of emotion and tone throughout the film. The combined use of these elements by Bong Joon-ho has created something with Parasite thats darkly humorous, compelling, dramatic, poignant, and bittersweet all at the same time. A bonkers, beautiful, radical, and drop-dead intelligent dark satirical tale of social inequality [and the] mock egalitarian weirdness of late capitalism.

In Bong Joon-ho’s flawless tragicomedy, a poor yet united family bluff their way into the lives of a wealthy Seoul household. Described by its creator as “a comedy without clowns, a tragedy without villains”, Parasite is more Shakespearean than Hitchockian – a tale of two families from opposite ends of the socioeconomic spectrum, told with the trademark genre-fluidity that has seen Bong’s back catalogue slip seamlessly from murder mystery, via monster movie, to dystopian future-fantasy and beyond. We first meet the Kim family, headed by father Ki-taek (Song Kang-ho) and mother Chung-sook (Chang Hyae-jin), in their lowly semi-basement home, hunting for stray wifi coverage and leaving their windows open to benefit from bugkilling street fumigation.

Described by its creator as “a comedy without clowns, a tragedy without villains”, Parasite is more Shakespearean than Hitchockian – a tale of two families from opposite ends of the socioeconomic spectrum, told with the trademark genre-fluidity that has seen Bong’s back catalogue slip seamlessly from murder mystery, via monster movie, to dystopian future-fantasy and beyond. We first meet the Kim family, headed by father Ki-taek (Song Kang-ho) and mother Chung-sook (Chang Hyae-jin), in their lowly semi-basement home, hunting for stray wifi coverage and leaving their windows open to benefit from bug-killing street fumigation. They have nothing but one another and a shared sense of hard-scrabble entrepreneurism. So when son Ki-woo (Choi Woo-shik) is faced with an unexpected opportunity to home-tutor a rich schoolgirl, he gets his gifted artist sister, Ki-jung (Park So-dam), to forge a college certificate, bluffing his way into the job and into the home of the Park family.

Perfectly accompanying the film’s tonal shifts is Jung Jae-il’s magnificently modulated music, which moves from the sombre piano patterns of the curtain-raiser, through the mini symphony of The Belt of Faith to the cracked craziness of cues in which choric vocals do battle with a musical saw. Just as the action can segue from slapstick to horror and back – sometimes within the space of a single scene – so Jung plays things straight even as madness beckons, ensuring that the underlying elements of pathos are amplified rather than undercut by pastiche.

by Cris O'Falt

by Cris O'Falt

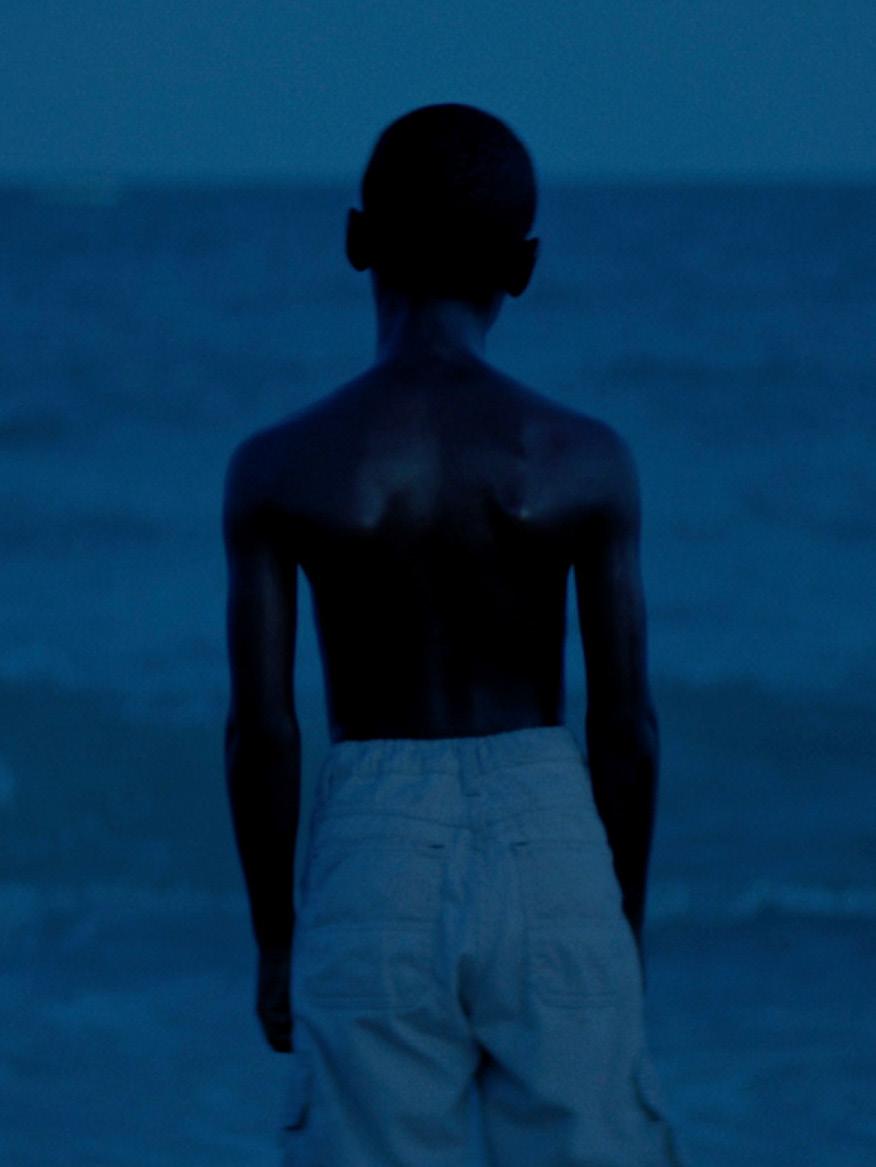

There’s an inherent visual tension in the look of Barry Jenkin’s “Moonlight.” Set in the harsh realities of Liberty City, an impoverished section of Miami where Jenkins and co-writer Tarell McCraney grew up, the sun-drenched neighborhood is filled with bright pastel colors and lush, tropical green trees and grass. “Tarell calls Miami a ‘beautiful nightmare’ and I think what we’ve done is paint this nightmare in beautiful tones,” Jenkins told IndieWire in a recent podcast. “We wanted to embrace the tension of that beauty, juxtaposed with the very dark things that are happening to the characters in the story.”

Right from the start, Jenkins and cinematographer James Laxton discussed wanting to move away from a documentary, or realist look, that has come to be expected

of American indies tackling social issues like “Moonlight.” They wanted a dreamlike feel that immersed the audience in the world of the protagonist Chiron, but that was also rooted in the color and light of Miami. Whereas many cinematographers play it safe in exposing dark skin tones, especially in harsh light, Laxton built his look around pulling rich, beautiful color from the actors’ faces while still executing one of the boldest lighting designs of the year.

To capture Miami, Laxton knew he’d want the actors’ skin to have a big shine, so the audience could feel the sun beating down on them. Building off this, he decided to warm the film's tones to further connect audiences.

There’s an inherent visual tension in the look of Barry Jenkin’s “Moonlight.” Set in the harsh realities of Liberty City, an impoverished section of Miami where Jenkins and co-writer Tarell McCraney grew up, the sun-drenched neighborhood is filled with bright pastel colors and lush, tropical green trees and grass. “Tarell calls Miami a ‘beautiful nightmare’ and I think what we’ve done is paint this nightmare in beautiful tones,” Jenkins told IndieWire in a recent podcast. “We wanted to embrace the tension of that beauty, juxtaposed with the very dark things that are happening to the characters in the story.”

Right from the start, Jenkins and cinematographer James Laxton discussed wanting to move away from a documentary, or realist look, that has come to be expected of American indies tackling social issues like “Moonlight.” They wanted a dreamlike feel that immersed the audience in the world of the protagonist Chiron, but that was also rooted in the color and light of Miami. Whereas many cinematographers play it safe in exposing dark skin tones, especially in harsh light, Laxton built his look around pulling rich, beautiful color from the actors’ faces while still executing one of the boldest lighting designs of the year.

To capture Miami, Laxton knew he’d want the actors’ skin to have a big shine, so the audience could feel the sun beating down on them. Building off this, he decided he would really push the contrast ratio in virtually every

scene, using a single source lighting scheme with no fill light, so the light would fall off into shadows and sculpt the characters’ faces. “When I saw those first test shoot images, I quickly realized James and Barry were really going for it and this was going to be a visually aggressive movie,” said colorist Alex Bickel, who has worked on a number of stylized indies, like “Kumiko, The Treasure Hunter,” “Blue Ruin,” and “Indignation.” “Barry certainly wasn’t playing it safe with the story and he didn’t want to play it safe in the visuals. That got me excited.”

Working with the colorist during preproduction gave Laxton the confidence of how far he could push the contrast on set and still make sure there was detail and rich color, especially on the cast’s dark skin tones when their faces were in shadows.

“The idea for us on set, at a base level, is to create an exposure that allows you to get into the DI [Digital Intermediate] with someone like Alex and have room to make color decisions in post,” said Laxton. “That’s true of every film, but especially ‘Moonlight,’ where there [were] greater opportunities to lose detail in potentially underexposed parts of the frame.”

Early during preproduction Jenkins and Laxton shared photos with Bickel as a way of expressing what they were looking for from the quality of light they wanted. “Then starting with the test footage, I could see the lighting ra-

tio and design they are implementing, and my job is to design grades that can achieve the emotional impact they are after,” said Bickel. With “Moonlight,” Bickel thought of the image in three distinct steps: create a nice thick color by pulling information out of the mid-tones, add blue to the blacks, and tease out the highlights so there’s white glint that’s on top of the image.