If there is one thing that connects all of us, it is our love for good Stories. Whether it be a romantic drama, a family entertainer or a science fiction, it allows us to peek and, many times, escape into a different world. History is one such story. Or, more accurately, all its sub-plots roll into one giant story.

This window into the past - our history - presents to us the realities that have come to define who we are, crafted and refined over centuries and millennia. Every piece of our history carries a story, a lesson, whose import may not be very readily decipherable to us. We visit historical places but may fail to truly visit the time in history and so miss the twists and turns that played out at that spot.

But what beautiful, inspiring and moving stories we would see if we were present in that period If only we could read and understand history for what it truly was.

This edition brings to you unfiltered, positive and wholesome stories and thoughts. A dancer's life-long love for Kathak, a painter's joy with vivid colours of Rajasthan, our relation with the fierce Tiger, a Maharaja's passion for our music and more. We round it up with a passionate plea on why history matters and how its lessons can be presented better to the next generations.

In a world of fast cars, fast food and fast fashion, it is not often that we have time to slow down to read and understand these stories. The end of the year is one such tiny slice of time; to slow down, savour, ponder and show gratitude for all things that have gone by.

We wish you a happy and story filled new year!

Ishan Singhal Ph.D Student in Cognitive Science. Football enthusiast. Amateur philosopher. ishansinghal@hotmail.com

Kalpana Dimri Sharma M.Sc in Physics and B.Ed. I started writing during my journey of treatment for Cancer. https://dilsekahaniya wordpress com

Ramya Mudumba Ph.D Student in Cognitive Science. Carnatic music student. Trekker. Poet. http://cloudsofthedusk.wordpress.com

Dr. TLN Swamy Doctor by profession. Flutist by passion with a zeal for penning and painting. drtlnswamy@gmail com

Bageshree Vaze Kathak Artist. Vocalist. Writer. Artistic Catalyst. www.bageshree.com www.pratibhaarts.com

Priyanka Banerjee Artist, Art Curator, Art Critic & Social Activist. Promoter of Tribal Arts & Artists

www.priyaban.com https://www.instagram.com/priya. ban/

Saisudha Acharya

Writer of interesting stories that escaped mainstream history textbooks and classrooms. Works as an educator and learning experience designer for a social enterprise.

Blog - The Untaught Historian

Check page 31 to see how you can contribute to our next edition.

In April 1998, I first walked into the compound of the National Institute of Kathak dance, popularly known as Kathak Kendra, in New Delhi. The tinkling of ghungroo bells and the distant boom of the Tabla drums greeted me as I walked along the stoned pathway that led to the back of the centre, to the main dancing hall where the living legend of Kathak dance Pandit Birju Maharaj taught his classes. Having received an Ontario Arts Council professional development grant, I came to Delhi to study this North Indian dance form. My training began by observing the students in Kathak Kendra’s 5-year diploma program. Just as writers learn by reading and musicians learn by listening, one of the main tenets of dance training is to learn by watching.

On the sprung wooden floor under swirling ceiling fans, men and ladies in their twenties danced in salwar kameez suits, dupattas pinned over their shoulders and waists, and ghungroos tied around their ankles. Maharajji sat on a carpet in front of them, propped against bolster cushions and chewing paan. An ensemble of musicians playing the Tabla, Sarangi, and Harmonium accompanied the class. I watched in fascination at the display of vigorous movements, intricate footwork, and lightning-fast spins on the left heel known as chakkars, the signature features of Kathak dance.

Every time I dance, I try to evoke the feeling of being in that room. I felt I had entered a portal into the past, to the darbar era when dancers and musicians were employed by the royal courts; this was the system of arts patronage in India that existed until it was dismantled by the British in 1858.

The Kathak Kendra students’ energy and thirst for achieving command over their art were inspiring, and it was a challenge for me to not jump up and join them When the students had trouble finishing a pattern to land on the sam, the first beat of the rhythmic cycle, Maharajji would chuckle in a goodnatured way, and stand up to demonstrate how to do it correctly. It was exciting to watch this legendary artist who had codified Kathak’s mudra or hand gestural language, and developed the dance form’s interaction with Tabla drum vocabulary.

I had been fascinated with Kathak much before I saw it performed properly. Growing up in St. John’s, Newfoundland, Canada, I saw glimpses of it in movies like Umrao Jaan. However, my Indian dance journey began with Bharatha Natyam, when the St. John’s Hindu Temple began holding classes in this South Indian classical dance style. I studied Bharatha Natyam for many years, completing my Arangetram (graduation recital) and eventually training in Mumbai with the late legendary Guru T.K. Mahalingam Pillai. I also studied Kuchipudi, another South Indian dance style. Yet from somewhere deep within my soul, I always felt I was meant to pursue Kathak. Since I was learning Hindustani (North Indian classical) vocal music – my father was a vocalist, as was his father – I felt more connected to Kathak because of its Hindustani aesthetic.

In 1997, Pandit Birju Maharajji performed with his troupe in Toronto, and then a few months later at Carnegie Hall in New York. I was fortunate to witness these performances. Maharajji made such a complex form seem so accessible by performing compositions that depicted everyday life, such as his famous ‘telephone tihai’ that I decided that if I were to study Kathak, I would learn Maharajji’s style. When I arrived in Delhi, it was the last days of Maharajji’s tenure as Head of Faculty at Kathak Kendra; he had just turned 60 years old and as per Indian law was required to retire. He would continue teaching as part of his institute Kalashram, where he taught until his passing in January 2022.

The origins of the dance form have often been romanticized to date back to the ancient temples of India, but as with North Indian classical music, there are obvious connections to India’s Mughal history. The story of Kathak’s evolution has been described well by scholar Margaret Walker in her essay Kathak in Canada: Classical and Contemporary. When India became an independent nation in 1947, there was a cultural revival to reclaim classical arts and minimize any British or Islamic influences, resulting in an ‘invented history’ of sorts. However, Kathak’s Muslim influences are evident in repertoire elements such as ahmad and salaami, as well as in the angarka or anarkali costuming.

Kathak is one of eight Indian classical dance forms, originating from and associated with North India, in particular with the states of Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan. The name Kathak is derived from the Sanskrit word katha which means a story.

While classical dance and music were performed in the darbar era -- Pandit Birju Maharajji’s father, for example, was a court dancer in the Raigarh princely state -- what we see now as Kathak is largely a product of the twentieth century. Treatises dating back to the thirteenth century describe court dance, including footwork, spins and a gliding walk, but Kathak's main feature today is its dialogue and interaction with the Tabla drums. As Walker has documented, choreographic fragments of past centuries were passed down through the generations - just as Indian classical ragas and melodic compositions have been passed down through an oral rather than written tradition -- resulting in a final fusion of Kathak as it is performed today on the proscenium stage. And Pandit Birju Maharaj is credited in particular as defining the style as hybridity of many artistic disciplines largely due to the fact that besides being a dancer, he was an accomplished percussionist, vocalist, composer, poet and painter.

It’s difficult to describe in writing the beauty of Kathak hand gestural language or the energetic beat language of the Tabla drums, but to watch Kathak is to witness a beautiful painting in process (it is no wonder Maharajji was also a painter). Kathak’s elegant and graceful movements are juxtaposed against hard-hitting footwork: it is the perfect balance of Tandava/Lasya, the integration of masculine and feminine energies. What is commonly referred to as ‘traditional’ Kathak is a solo art form, performed by a dancer with an ensemble of musicians.

The trajectory of a performance will usually begin with an invocation to a deity such as Shiva or Saraswati, and continue with fixed rhythmic patterns such as thaat, ahmed, uthaan, tihai, paramilu, and paran. A particular rhythmic cycle is chosen and exploration begins in the vilambit, or slow tempo, continues in madhyalaya, medium tempo, and finally in drut or fast tempo. A dancer will end a composition by striking a pose to hit the sam, the first beat of the cycle, and this explosive effect makes Kathak highly dramatic. Instruments such as the Sarangi, Harmonium and Sitar play a nagma or lehera, a melodic line that repeats to demarcate the rhythmic cycle, while the Tabla artist plays both fixed compositions and interacts with the dancer in improvised sequences. A dancer recites rhythmic patterns, and this recitation is known as padhant. It is imperative in the Kathak style that the dancer vocalize rhythmic language, and this is unique to Kathak, as the other Indian classical dances do not require a dancer to recite rhythmic language on stage.

There are repertoire elements in Kathak that focus less on rhythmic complexity, such as the Gat Nikaas, evocative of the darbar era, in which a dancer performs the gliding walk or the chaal. Gat Bhav allows the dancer to demonstrate abhinaya or facial expression. A traditional Kathak presentation will often feature a lyrical piece such as a thumri and often culminate with a lively fantasy of movement known as a tarana.

The traditional system of training in Indian classical arts is known as the Guru-Shishya parampara, wherein a student lives with their Guru, but with the advent of Independence in 1947, the Indian government set up institutions for the learning of classical arts. Kathak Kendra was first established in 1955 as part of the Shriram Bharatiya Kala Kendra, and in 1964 it became part of the Sangeet Natak Akademi.

The late Pandit Shambhu Maharaj, the uncle of Pandit Birju Maharaj, was the first head of faculty at Kathak Kendra After he died in 1970, Pandit Birju Maharaj Ji took over this position During his tenure, Maharajji adapted what was traditionally a solo form by choreographing group pieces.

Maharajji and Pandit Shambhu Maharaj practised the Lucknow style of Kathak, but eventually the Kathak Kendra faculty expanded to include exponents in the Jaipur style or gharana of Kathak.

Kathak Kendra is the premier institution for learning this art form, but now Kathak schools exist all over India and in all corners of the world (just as other Indian dance styles have become transnational art forms)

One will find differences in the different gharanas of Kathak (just as one finds in the different schools of Bharatha Natyam, Odissi, Kuchipudi, etc.); some of these are minute differences in the angles of arms, footwork and chakkar techniques, or the use of the upper body in the Lucknow style. Generally, however, there is an overriding aesthetic common to all Kathak interpretations, especially in its interaction with the Tabla drums. It would be impossible to name all the notable Kathak legends but they include Gopi Krishna and Sitara Devi of the Benares gharana, Kumudini Lakhia, Maya Rao, Rajendra Gangani, Saswati Sen and many others. Contemporary Kathak choreographies range from the retelling of epic stories such as The Mahabharata or Ramayana to explorations of social and political themes, and collaborations with other dance languages (such as Flamenco).

There is a popularly held notion of Kathak and Indian classical arts as ‘traditional,’ yet they are living art forms. In my study – I trained primarily with Jaikishan Maharaj, and with Maharajji himself -- I learned rhythmic compositions created by my teachers, and not anything written down in a book. I witnessed how they composed rhythmic patterns on the spot, and I came to know Kathak as an art that is created in the moment. Hence, Kathak is not simply a reflection of the past, of a transplanted Indian identity, or in the case of Canada, a ‘multicultural’ dance form. Kathak evolves all the time with individual interpretations, and contemporary expressions reflect the present moment while drawing on traditional foundations.

Over the past two decades I have had the great privilege of studying with other exponents in movement and rhythm including Pandit Pratap Pawar, Pandit Puran Maharaj and the late Srimati Maya Rao. In 2010 I performed as a solo artist in Maharajji’s annual ‘Vasantotsav’ festival at Kamani Auditorium in New Delhi, with Chief Guest Sitara Devi in the audience. And with such blessings, I continue my Kathak practice as one that is constantly evolving by composing and choreographic new rhythmic and melodic material, interacting with other styles and aesthetics, and producing theatrical productions.

In particular, I have tried to enhance Kathak practice by producing music that can be used for performance and teaching. The greatest challenge for dance artists is how to access music. In the 1980s, Maharajji released an album of music for Kathak dance, which included his famous Kalavati Tarana (to this day many dancers perform on that song) but beyond this, there are virtually no commercially-available recordings for dance. Kathak presentation ideally features live musical accompaniment, but it is often untenable for dancers to engage musicians; dancers must have the financial resources to cover musicians’ fees, and there are a handful of full-time musicians who perform for Kathak dance outside of India. The only other option is to produce professional-level studio recordings, and this is also not feasible for dancers on a regular basis.

Therefore, in 2007, I began using my vocal and composition skills to produce music for Kathak dance performance and training, beginning with my album Tarana (released by Times Music under the name Khanak). Later albums include Ragas and Rhythms, Avatar (9), and Kalashree. In these recordings I have adapted and sung traditional compositions as well as original songs and arranged them as they would be performed for Kathak choreography by interweaving melody with rhythmic compositions. Recorded at Toast and Jam Studios in Toronto and featuring a stellar lineup of musicians (Vineet Vyas, Ajay Prasanna, Murad Ali to name a few), these recordings are digitally accessed by dancers around the world through platforms such as Spotify and ITunes. Many of these choreographic interpretations can be found on YouTube, and in 2016, a dancer performed one of these songs at London’s Wembley Stadium on the occasion of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to the United Kingdom.

I have recently completed a video project entitled Tarana, co-produced by the Aga Khan Museum, in which I have performed the choreography of some of my Kathak recordings. Technology and digital platforms have connected artists especially during the pandemic and are proving to be powerful tools in cultivating the global field of Kathak. Pursuing any art form is a lifelong journey. The story of Kathak is one of resilience and evolution and my journey with it continues.

By Ishan Singhal

By Ishan Singhal

Image Credit: Sudarshan Shaw

Image Credit: Sudarshan Shaw

When we hear of the Tiger, all of us instinctly place it as our national animal. Why the Tiger one might ask?

If by chance you remember history and civics from school, you may recall that the Tiger is supposed to symbolize grace, strength, valor and enormous power. And was thus chosen to inspire these qualities in us. But is that it?

We thought for this article we would explore the cultural ties between the Tiger and our land, going as far back as we could Our distant ancestors understood that they could not survive alone and without the compassion of the essences of coexistence between man and animals To the early inhabitants of India, the Tiger was a potent representative of this coexistence. She had hunting skills without parallel, was magnificent in her svelte striped coat and incredibly powerful.

Many early people sought to identify themselves with her; some viewed her in awe and fear, while others revered her as the protector. Below is a summary and a glimpse into the amazing history of India and her Tiger.

For more than 10,000 years images of the Tiger have been cast on Indian soil Whether it be art in the form of cave drawings, marble carvings, petroglyphs, emblems, coin printing, temple pillars or royal courts. The Tiger has been a major art and cultural motif in almost all regions of India. The oldest depiction of the Tiger is housed amongst the rock art of Bhimbetka caves in Madhya Pradesh Dated to be at least 10,000 years old!

Another prominent appearance of the Tiger in our history, is in the Indus Valley Civilisation. Several seals and coins bear images of the Tiger. From everyday coins, to seals where a hero is depicted holding two tigers to even the famous Pashupati (God of animals) Seal. All of these are believed to be somewhere between 2,000 and 4,500 years old. It is believed that animals on these seals were worshipped at the time. The Tiger was famed in the same regard even in the south of India.

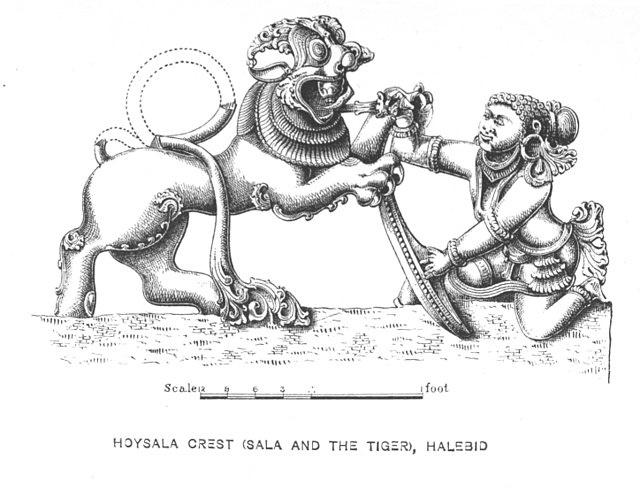

The‘Jumping Tiger’ was the royal emblem of the Chola dynasty, appearing on its flag, coins and banners. Similarly, even the Hoysala empire of present-day Karnataka had the Tiger as its emblem In fact some believe even the name ‘Hoy Sala’ comes from the boy in the emblem (Sala) being asked to strike (Poy) at the Tiger Showing us that even then, our ancestors looked up to the Tiger.

Pashupati seal, Source: Wikipedia

Flag of Chola, Source: Wikipedia

Pashupati seal, Source: Wikipedia

Flag of Chola, Source: Wikipedia

Moving onto religious motifs, the revering of the Tiger is again universal. The tiger is the vahana of Shakti and Goddess Durga. While also being the vahana of both Ayyappa of Sabarimala and the planet Rahu. The Tiger is also itself worshipped as a deity in several parts of India For instance, as Waghdeo or Waghoba in Maharashtra and Huliraya of Karnataka. Finally, in tiger heartland of Sunderbans, Goddess Bon Bibi of Bengal, the guardian spirit of the Sundarbans herself rides a tiger. Many tribal communities believe in co-existence with the Tiger, and see her as the protector of the forest Tribal communities of Bhaina, Bharia, Bhatra, Dangis, Gond, Gosain, Kol, Korku, Koshti, Velip, and Warli, all worship the Tiger as a diety. Indian traditions across states have venerated and protected this beautiful animal even in regilous beliefs

Across states, cultures, geographies and beliefs, the Tiger has been admired and celebrated in India. It is no wonder then, that today we are trying so hard to make sure that the Tiger continues its legacy. Approximately 3,000 tigers are present today in more than 53 Tiger conservation reserves in India. But it may surprise you to know, that even conservation efforts for the Tiger are not very new. The first Tiger conservation efforts were made during the Mauryan empire (2,500 years ago!). The political and economic texts of Arthashastra of this empire mention forest officials who were designated to keep forests healthy and safe Moreover, areas of the forest were designated as safe zones where no hunting or tree felling was allowed. This was to allow specific zones were no human interference would take place.Thus wildlife protection history traces back to Chandragupta Maurya in India. His legacy was carried forth even by Asoka in ensuring that forests and its Tigers were protected.

Goddess BonBibi of Sunderbans, Source: Wikipedia Waghoba

Goddess BonBibi of Sunderbans, Source: Wikipedia Waghoba

In looking back at how our land has celebrated the majestic Tiger through time immemorial, it gives us a reminder of the principles of co-existence. A line from Mahabarata captures this principle perfectly It reads “nirvano vadhyate vyāghro nirvyāghraṃ chidyate vanam| tasmādvyāghro vanaṃ rakṣedvayaṃ vyāghraṃ ca pālayet”. It can be translated as “Without the forest, the tiger dies And without the tiger, the forest dies Hence, the forest protects the tiger and the tiger guards the forest”. The admiration, adoration and conservation of the Tiger stands as a universal value system across the history and expanse of India We celebrate not only the Tiger, but how it brings us together

“Without the forest, the tiger dies. And without the tiger, the forest dies. Hence, the forest protects the tiger and the tiger guards the forest”

1906 - 1980

What I see with my eyes in this world’s garden in the light of day, I represent in my painting; what I touch and feel in it’s darkness, I embody in my sculpture

who crafted our heritage

Ramkinkar Baij, a Padma Bhushan awardee, is regarded as one of the finest sculptors of India. He was also a painter and a well known teacher at Kala Bhavan.

Some of his famous sculptures include - Lady with Dog, Sujata, Santhaal Family, Mill Call, Yaksha-Yakshi (Jokkho-Jokkhi).

Below are some of his sculptures:

Source: Wikipedia, Internet

By Priyanka Banerjee

By Priyanka Banerjee

These beautiful lines speak to the eternally beautiful architecture of Rajasthan. The princely state known for its remarkable cultural heritage has inspired me and my artistic endeavours. I share my paintings, hoping that the desert winds touch your heart just like they did mine.

In ancient times, the women in purdah could see the events outside without being spotted themselves.

"Architecture should speak of its time and place but yearn for timelessness."

- Frank Gehry

The princely state is replete with mesmerizing landscapes and palaces speaking of innumerable tales of the bygone era. Enduring the unmerciful desert winds and oppressing heat of the scorching sun, the state has witnessed many unshakable sieges and has provided a safe haven for its rulers and residents during times of conflict and peace.

The hospitality and tenacity of the Rajasthani people have always touched me. Their smiling faces, long moustaches, sun-kissed bodies, colourful attires and vibrant turbans in their unadulterated forms have been my favourite subjects to draw.

It's my endeavour to depict the opulence of architecture and depth of character of the native people of the jewelled state of India - Rajasthan.

I always find a perspective to transform my ordinary themes into something extraordinary. If my artwork offers happiness to its viewers, I shall consider my efforts worthwhile.

The tired shepherd leading the herd of sheep through the meandering fields, the eternal glory of majestic Mehrangarh fort, the ruins of Chittorgarh reminding of the Jauhar of Queen Padmini, the conversing camel owners of Pushkar fair and more, always invite one and all. I hope you come and experience the warmth of the people who still sing from their hearts and ask travellers to 'Padharo Mhare Desh.'

Rajasthan, through my eyes continues here.

By Saisudha Acharya

By Saisudha Acharya

One day, my son, who was very young at the time, was looking at a picture of Krishna and Arjuna in the middle of Kurukshetra battlefield. He suddenly turned to me and asked if, when I was growing up, I had a horse drawn carriage like Arjuna’s. In his imagination, I had gotten on my carriage in the Iron Age and ridden through the various revolutions of agriculture, science, and technology, to finally arrive in this golden age of YouTube, WhatsApp, Swiggy and Uber.

When I was also around my son’s age, I had apparently asked my mother if she had been there at the same time as Jesus Christ. It seems like all little children try to grapple with this abstract concepttime. We experience it as we live it, but it is nearly impossible to fully comprehend time once it goes beyond our lived experience. How long are a hundred years really? How about a thousand?

Eleven-year-olds, who have only lived for a little over a decade, are naturally curious by what happened in the past. But, in my experience, that curiosity vanishes when the teaching of history becomes all about timelines and periods.

To complicate matters more, we talk about histories that are so far removed from us in both time and space (geographic location) that one math teacher asked me rhetorically - “What does it matter what happened with some king in some far kingdom in some century?”

This is a very valid question – one that many a bored child who is having to memorise answers to questions on Ashoka’s battle with Kalinga or Ashoka’s role in the spread of Buddhism wants to know – why does this matter?

Although, I had vaguely learnt about the discovery of Ashoka’s pillars and James Princep’s role in decoding Ashoka’s inscriptions in school, I had not really understood the significance of this fact till I was an adult and had a better concept of time.

Ashoka lived in the 3rd century BCE. James Princep worked on decoding inscriptions from Ashoka’s pillars and rock edicts in 1836. There was a space of 20 centuries between the two men. These ancient pillars and edicts were silent witness to 2000 years of Indian history and had become part of the landscape.

“What does it matter what happened with some king in some far kingdom in some century?”

It also means that Ashoka is both ancient and modern. While Ashoka belonged to a time that we cannot really imagine, he is also a fairly new addition to the history of the Indian-subcontinent.

He arrived on screen in 1836, and a little over one hundred years later, the lion capital atop one of his pillars was selected as independent India’s new State Emblem and the Ashoka chakra was at the centre of our flag, replacing Gandhi’s charkha.

Why the dramatic rise to stardom? This is because Ashoka’s story (according to his inscriptions) embodied the values of a culturally diverse region that was coming together to form a single nation. In other words, it was all about timing – Ashoka was brought back to life at just the right time in history.

A d d i t i o n a l R e a d i n g Discovery of the lion capital in 1905 and how it became the cover of our Constitution How the chakra came to be part of the flag

At a time when the country was being ripped by communal violence, we needed an inspiring figure from history who did not belong to any one of the major religious groups and who was far enough away from us in history to not become controversial. Ashoka was Buddhist. He preached nonviolence. His kingdom expanded across a vast part of what was to become modern India – uniting under his rule many different diverse groups of people whom he treated with respect and fairness.

While a new India was being born, Ashoka was reminding citizens that these values of non-violence, magnanimity, and unity in diversity, were all part of our cultural and social fabric for thousands of years. They were not modern, western ideas but fundamental to our identity as Indians.

In schools, we study history to put together a context for our current social, cultural and political life and to define a national identity. We emerge from the caves of Bhimbetka, and through a series of adventures and misadventures, arrive in this present moment of 21st century India and each chapter serves to paint a fuller picture of our lives today.

However, I also think that history serves as a wonderful pedagogical tool to attend to the more central goals of institutional education – which are to inspire curiosity, provide contexts for reflection and critical thinking, and to provoke action.

In 1905, a Public Works Engineer and part-time archaeologist, F.O. Oertel, made a magical discovery at Sarnath. He found Ashoka’s lion capital, among several other beautiful treasures. The image below is a photograph of his dig. Note the pillar standing in the middle of the foreground, immaculate among all the rubble.

It was here at Sarnath that in March 1905 he unearthed the Lion Capital of Ashoka of an Ashokan pillar, which was to become the national emblem of India

Photograph of Archaeologist F.O. Oertel's discovery at Sarnath.

Source: Archaeological Survey of India GoI

While Ashoka’s life and philosophy is inspiring, 11- and 12-year-olds are often more fascinated by the story of Ashoka’s rediscovery. “That means, there could have been other kings and queens like Ashoka, but maybe we don’t know any more because their pillars broke in a cyclone or something?” one child considered out loud. It leads us to reflect on this idea that not all great men, women or villains are remembered forever. That one day, if material evidence of our lives disappears, our time on this earth will be forgotten too. It explains culture’s obsession with leaving behind architecture and artwork as a form of legacy.

But, what does this say about the short shelf life of fame in this age of YouTube and Instagram influencers and celebrities, people who have left an ephemeral digital footprint in a physical world that can only preserve material evidence of our thoughts and ideas? Or, how does this impact our perspective on the conservation of art, artefacts and nature – all of which are part of our identity?

Also, is history the only vehicle for reflection? No, of course not. Science, literature, art and math all also get children to reflect and think more deeply. But history adds spice. It is the lasso that is thrown in your direction and draws you into a subject by providing context to all learning.

A chapter on standard units of measurement in math and science can be dull… until you tell your class a story from the past when NASA lost a $125 million Mars Orbiter because of a silly math mistake.

In 1999, teams from NASA and Lockheed Martin lost a whole orbiter space craft simply because one team was using the Imperial system of units (inches, feet, etc) while the other used the metric system of units (centimeters, meters, etc). No one noticed till the orbiter was up in space. Children laugh and marvel at the silliness of this story, but when their math teacher is being annoying by insisting that the child write out the units of measurement for every geometry problem, the child might link it to a realworld consequence of not doing that.

Using the story of NASA’s careless mistake in a math class is using history as a pedagogical tool to get children engaged with the subject. But it also gets children to think about the importance of paying attention to the details, or about how small seemingly insignificant missteps can have disproportionately large consequences, or even about how mistakes happen all the time – even literal rocket scientists make mistakes.

If I am ever asked why some king, in some place, in some century matters again, I think my answer is that it does not really matter at all. History is vast and full of a thousand episodes that compete for inclusion in middle school classrooms around the world. When it comes to history, we need to select stories based on our intention. What are we intending to illustrate or convey?

But conversely, when we read history (not just in a textbook, but also through the news, social media and in conversation), it is our job to identify the intention behind why this chapter of history is being told to us. The writer or speaker is trying to illustrate a point, defend an argument, or persuade you of a philosophy. It is your job as a reader of history to think critically and decide whether you agree or disagree, believe or question.

And so, it becomes a history educator’s job to empower the child to think critically, analyze and play the role of gentle sceptic who asks the right questions, without accepting all stories at face value.

This way, history teaches children to become independent thinkers, less likely to be swayed by the loud rushes of opinion that they are always exposed to. It is a skill that they can use in whatever they want to do in their adult lives.

On a warm April day almost 2 centuries ago, Travancore rejoiced the birth of a prince - Swati Thirunal Rama Varma - to the Queen Gowri Lakshmi Bayi and Raja Raja Varma Koil Thampuran. While the Queen and the King welcomed an heir and the future king, little did they know about the joys Swati Thirunal would leave behind that would inspire several generations to come.

Perhaps there was some whiff in the air about the prowess of the new prince, for it is believed that upon his birth, the Queen had requested the venerable and renowned poet Irayimman Thampi to compose a song, and he penned the famous lullaby - Omanathinkal Kidavo - that continues to be sung to this day.

Born in the backdrop of a potential annexation by British India under the Doctrine of Lapse, the poem's lyrics reflect this sense of relief when it refers to the baby as a 'treasure from God' and 'the fruit of the tree of fortune.'

The prince would grow to share his treasure with us all in due course.

Maharani Ayilyom Thirunal Gouri Lakshmi Bayi Swati Thirunal's Mother Source: WikipediaSwati Thirunal's ascension to the throne was preceded by an education that was comprehensive. Under the guidance of his father, a well versed Sanskrit Scholar himself, he became proficient in several languages including Malayalam, Kannada, Telugu, Tamil, Marathi, Sanskrit, English and Persian.

Another important language Swati Thirunal developed even as a child was the language of Music. He was instituted into Music at a very early age and studied the classical forms of music from Karamana Subrahmania Bhagavathar and Karamana Padmanabha Bhagavathar. He is also known to have had keen interest in both the classical music systems of India - Carnatic and Hindustani.

Swati Thirunal took over the governing of the Kingdom at the young age of 16. Even as he governed the kingdom, with the backdrop of the British rule, his interest in music ensured that he become a great patron of many musicians and art forms. His Kingdom became a hub for artists, musicians and scholars.

Swati Thirunal's palace became a home to many musicians and artistes of the period, including the famous Thanjavur Quartet brothers, Tyagaraja's disciple Kannayya Bhagavathar, Ananthapadmanabha Goswami (a Maharashtrian singer), Shadkala Govinda Marar, and many others. All this provided the perfect atmosphere for him to not only elevate his knowledge of Carnatic music but also to spark his own growth as a composer.

While he had a special bond with Carnatic music and had several musicians, poets and composers in his court, he is also known to have given patronage to a great number of Hindustani musicians. Swati Tirunal's reign came to be cherished as one of the greatest era for the patronage of music and arts.

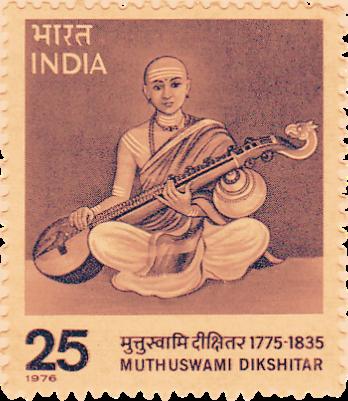

A portray of young Swati Thirunal with his father, Raja Raja Varma Koil Thampuran Source: WikipediaIndian classical music owes much to its many celebrated composers. From Purandara Dasa, known as the Father of Carnatic Music, to the famed Trinity - Tyagaraja, Dikshitar and Syama Shastri - and many others including Annamacharya, Narayana Theertha, Vijaya Dasa, Kanakadasa, Vadiraja Tirtha, Arunachala Kavi, Bhadrachala Ramadas, Sadasiva Brahmendra and Oottukkadu Venkata Kavi, these composers have carried the flame and beauty of the Carnatic music through their timeless compositions which fill the sabhas and auditoriums even today.

Though not as prolific in terms of the number of songs composed, Swati Thirunal's compositions gained much popularity due to their beauty and depth. Swati Thirunal is known to have composed about 400 songs in different languages.

His compositions show his range which includes Padams, Varnams, Keerthanams, Swarajatis. He has also composed several Dhrupads, Khayals and Bhajans as well which indicate the versatility of his musical understanding and appreciation. Swathi Thirunal used many mudras - Padmanabha, Pankajanabha, Sarasijanabha, etc. in his compositions. Almost all the compositions are addressed to Lord Padmanabha, his family deity.

There are many favourites among the music loving fraternity, but the ones that are very popular are Bhavayami Raghuramam, Deva Deva Kalayami, Paripalaya Mam, Pannagendra Shayana, Paramananda, Bhogindra Sayinam, Aliveni. Aaj Aaye and Karunanidhan are two of his Dhrupads that are regularly heard in the music circuits.

F

Top Row - Tyagaraja (left), Syama Sh (middle), Muthuswami Dikshitar (ri Bottom Row - Annamacharya (l Purandara Dasa (midd Kanaka Dasa (ri ind a compilation of the songs crafted by Swati Thirunal here!

Deva Deva Kalayamite

Mayamalava Gowda

Gopala Pahimam Mayamalava Gowda

Pannagendrashaya Ahiri

Thillana Dhanashree

Shree Padmanabhaswamy Temple, Thiruvananthapuram

The principal diety of the Royal Family of Travancore

Deva Deva Kalayamite

Mayamalava Gowda

Gopala Pahimam Mayamalava Gowda

Pannagendrashaya Ahiri

Thillana Dhanashree

Shree Padmanabhaswamy Temple, Thiruvananthapuram

The principal diety of the Royal Family of Travancore

While the songs of Padmanabha may be his signature, the Navarathri krithis are equally notable. The Navarathri krithis consist of nine compositions intended to be sung during the Navarathri festival conducted in the month of September/October. These songs are composed in the Sanskrit language and bring to fore Swathi Thirunal's poetic command, brilliance and the utmost bhakti all at the same time.

Of these nine krithis the first three songs are in praise of Saraswathi, the next three on Goddess Lakshmi and the last three in praise of Goddess Parvathy. The nine krithis include Devi Jagajjanani, Pahi Mam, Devi Pavane, Bharati Mama, Janani Mamavameye, Sarouhasana Jaye, Janani Pahi, Pahi Janani Santatam, Pahi Parvata Vardhini.

About Swati Thirunal's contributions to music, the late composer Mysore Vasudevachar is believed to have once remarked:

“One should see this great padmanAbha to get at the secret of the greatness of Maharaja's compositions, for they are verily the very voice of Maharaja pouring out his heart to his Maker. Unless the words and the music we compose simultaneously breathe a feeling of oneness with the Supreme, a composition does not come to life. Swati Thirunal's compositions are immortal because we see padmanAbha in them''

He was truly a Maharaja among the Carnatic composers notwithstanding any controversies about the attribution of his compositions. While one enjoys the music and songs, there is no doubt that music connoisseurs would have had many more compositions to rejoice but for his untimely death at the young age of 33.

Swati Thirunal's legacy continues to live on today in the artists who sing his beautiful and captivating compositions. The annual Swati Sangeethotsavam music festival is a tribute to this Maharaja among composers.

Prince Rama Varma, a descendant of the Royal family, continues to spread the beauty of Swati Thirunal's contribution.

Passionate, diverse and experienced Indians write about these subjects to bring a smile to your face.

Let's keep the smile growing.

Share your email here to not miss the future editions.

Sometimes, during my meal, it astonishes me how little I know about the hands that harvested these rice grains, the lands where the vegetables are picked, the long history of the seeds that went through several life cycles to appear on our plates. Soil is life. Seed is life From farms to our plates (and much more), we are inexplicably dependent on them for our survival. This article is a humble attempt towards inspiring thought towards them.

There is a rise in awareness about preserving indigenous/native seeds and why this is important in the current times. Farming experts and farmers themselves claim that the HYV( high yielding variety) or hybrid seeds, in contrast to giving high yield, are quite sensitive to climatic changes. This would mean that a hybrid crop doesn’t give the ideal output, for example, if the rains are too scant or even too much. That is, the HYV crops constantly need management of not just water but chemical fertilisers and pesticides as well So, the demand for the chemical treatments went up with the demand for the yield. In turn, the soil quality and life got degraded, also while the chemicals entered the systems of people and animals that consume the output. The cost we are paying now is huge. Traditional agricultural practices have been forgotten, we have polluted our soil and water, we have new allergies that weren’t common before, and farmers are always on the edge.

The indigenous seeds are resilient to environmental and climatic variability, bring genetical diversity back and make agriculture more sustainable. The crops are also resistant to diseases and pests, and have a direct influence upon soil health and nutrient levels.

For this cause, several Indian villages observed seed festivals in the last few years. Women farmers from Kandhamal district in Odisha, came together carrying pots of indigenous seeds over their heads to share knowledge and seeds in a celebratory manner. In this annual festival, farmers pray to the Earth goddess (Dharani Penu) for good harvest and move onto displaying various indigenous seeds like finger millet, foxtail millet, jowar, oilseeds, maize, several types of rice, herbs, wild roots etc The farmers claimed that these seeds don’t require any fertilisers or pesticides for them to grow and the yield is nutritious and tastier. Women farmers act as guardians of these seeds and preserve them every harvest year in these communities. The festival ends in vigour with drums, cymbals and chants and sharing these seeds with each other.

Special mention to Nirman, an NGO which is actively working in seed preservation and ecological farming. They organised seed festival (2019) in Gambharikhol village in Odisha and with the help of the frames collected 50 indigenous seeds of rice and grams. They distributed the seeds to 18 different villages in the kharif season to inspire change and revive traditions of seed sharing.

National indigenous seed festivals are also facilitated by many organisations like Sahaja Samruddha, Bharat Bheej Swaraj Manch, ASHA-Kisan Swaraj and Save our Rice campaign In October 2020, such a national festival is conducted online where farmers showcased and exchanged knowledge. Save our Rice campaign is active in 5 states including Kerala, TN, West Bengal to bring back the nutritious varieties that were prevalent in the olden days. The government also proposed several initiatives in this regard. The National Gene bank (NGB) at ICAR-National Bureau of Plant Genetic Resources (ICAR- NBPGR), New Delhi is already playing a part in conserving around one lakh varieties of indigenous seeds. Initiatives like Assam’s ‘Native Basket’ and Himachal’s ‘Mountain Grain’ were launched where 24 indigenous rice landraces in Assam and 2 in Himachal are identified and being promoted Did you know that our country has 161 state and 6 central seed testing laboratories that analyse seed quality on various factors?

Many noteworthy individuals are actively working towards this rising tide. The recent PadmaShri awardee Rahibai Popere of Maharastra, an inspirational women farmer, preserved almost 114 different indigenous varieties of 53 crop seeds. She realised that her grandchildren were getting sick often and that it about selecting seeds and traditional agricultural techniques and inspiring them towards sustainable ways. She has a whopping 13000 women working for her, which she humbly gives credit to, for the Padma Shri. She planted 5000 sampling of hyacinth seeds and distributed them to SHGs across 25 villages.

was due to the chemicals heavily used in farming. Remembering her father’s words ‘old is gold’, she just starting storing the old varieties. She has won many awards and started her own self-help group called ‘Kalsubai Parisar Biyanee Samvardhan Samiti’ through which she trains farmers

This brings us to the question- how to eat right? How do we make efforts towards this cause? The only way is to increase our knowledge about such varieties and the good they bring to our lives. One could make efforts to get to know the once-prevalent local varieties and the various events/places where one can access these Visit local farmer markets If you have space, you could start small by planting them. Hybrids (veggies or fruits) might look cleaner, brighter and fancier (seedless even) but we need to assess the pros and cons and take an informed choice.

By Dr. TLN Swamy

By Dr. TLN Swamy

Read the first in this two-part article series here.

परा कवीना गणना�स� क�न��का�ध��तका�लदासा।

परा कवीना गणना�स� क�न��का�ध��तका�लदासा। purā kavīnām gananāprasange kanisthikādhisthitakālidāsā। purā kavīnām gananāprasange kanisthikādhisthitakālidāsā।

अ�ा�प त��यकवरभावादना�मका साथवती बभव ॥

अ�ा�प त��यकवरभावादना�मका साथवती बभव ॥ adyāpi tattulyakaverabhāvādanāmikā sārthavatī babhūva ॥ adyāpi tattulyakaverabhāvādanāmikā sārthavatī babhūva ॥

In ancient times, when all the poets were counted, Kālidāsa was assigned the little finger. But, no poet of genius comparable to his has existed till today; hence, the finger next to the little finger (i.e., the ring finger) is meaningfully named as ‘anāmikā’.

That is how the Indian tradition described the Mahakavi of Indian Poetry Kalidasa, a poet with no one to match him so far. Despite being immensely popular through his poetic works, very little is known about his private life. He seems to have lived around the 5th century CE. Though some scholars claim his origins to be from Kashmir, he seem to have travelled all over India and spent his prime poetic age in Ujjain as the court poet of king Chandragupta II.

Legend has it that he was quite a moron to start with and had been married to a princess via a plot by the courtiers to upset the proud princess, making him act like a wise scholar. After the truth was revealed, stung by the scornful words of his wife, he prayed intensely to find the favour of the Goddess of intellect Shyamala, who turned him into a poetic genius His very first poetic verses after the transformation were the popularly recited Shyamala Dandakam "Manikyaveenam upalalayanthim".

After his transformation, he created great poetic works as the amorous "Meghadutam", romantic "Ritusamharam", utopian "Raghuvamsham" and the classical "Kumarasambhavam" His body of work has set impossible standards in Indian poetry, adding a different dimension of romanticism to the thus far 'puranic' and philosophical literary works. He took the story telling to an entirely different narrative through his universally famous 'Dramas' "Malavikagnimitram", "Vikramorvashiyam" and the most admired "Abhignyana Shakunthalam" which many foreign writers translated into their languages like English and German, etc.

His death also has been attached to a legend of murder by a courtesan who got greedy for a reward announced by the Ceylon king Kumaradasa to complete the second line of a verse puzzle the king posted. Kalidasa, who completed the verse as soon as he came across it in the courtesan's house, was murdered by the courtesan to claim the credit and reward for herself. Later the fraud was discovered, but the king seemed to have consigned himself to the funeral pyre of his friend Kalidasa in immense grief. It is hard to prove the authenticity of these legends, but regardless of their genuineness, they reflect the tremendous popularity enjoyed by the legendary concerned person.

Moving from Kalidasa, who belonged to the 5th century, let's look at one of India's foremost dramatists, poet Ashwaghosha. He earned his nickname for the legendary way he made even some starving horses listen to his teachings, who preferred it over the meal provided to them. Believed to be born in Ayodhya in the 1st century CE, he wandered all over India as an ascetic, teaching and writing, finally ending up serving in the court of Kanishka. His critical work was writing of the epic about the life of Buddha called Buddhacharita in Sanskrit, which became famous not only all over India but also across China and other South-East Asian countries through its adaptation into their local languages.

Another first-century poet named Hala was, in fact, a Shatavahana king who ruled the current-day Deccan region. He is known for his famous poem called "Gathasaptashati."

Bhartruhari is a 5th-century poet famous for his 'Shatakatraya" Subhashita deals with the practical applications of morals and philosophy in daily life. It is widely quoted all over India on how to lead one's life. He is also known for his other work on Sanskrit grammar called "Vaakyapadeeya," dealing with theories on words and sentence formation, including linguistic philosophy.

Banabhatta is a 7th-century poet and prose writer from the court of the Emporer Harsha in north India, Kannauj. Bana is credited with one of the world's first novels, "Kadambari," apart from the "Harshacharita," a biography of King Harsha.

Amarasimha, is another notable poet from the 4th century CE, a Sanskrit Grammarian and one of the nine gems in the court of king Vikramaditya of Ujjain Most of his works were lost except for the exceptional "Amarakosha," a metered compilation of 10,000 Sanskrit words, probably the world's first lexicon.

Bharavi is a 6th-century poet from Southern India and is known for his epic poem "Kiratarjuniya," which is considered one of the six mahakavyas in classical Sanskrit and regarded as the most powerful poem in the Sanskrit language.

One of India's most important first-millennium Sanskrit poets is Adishankaracharya, a philosopher-poet and a religious guru of enormous influence in reviving the declining Sanathana dharma around the 8th century CE. He is religiously followed for his teachings of "Advaitha Vedantha" which declares that "Aham Brahmasmi," i.e. the self "Atman," is the manifestation of the Almighty "Brahman" himself, and both are the same. He has also written excellent philosophical commentaries in the principal Upanishads called "Brahmasutrabhashya" and on the all-important Hindu scripture "Bhagavadgita," popularizing it further by explaining its cryptic message to the world.

In his short life span of just 32 years, Shankara travelled extensively all over India and established many monasteries called 'Matha's across the country, like the principal four at Shringeri, Puri, Badri and Dwaraka. These were set in all four directions of India and many other important places like Kanchi. During his extensive travels across the country, he met many contemporary scholars and participated in public philosophical debates with different orthodox schools of Hindu philosophy and succeeded in convincing people about the true essence of the Upanishads and 'Advaitha.'

Born in Kaladi of Kerala, Shankara lost his father soon and wanted to become a Sanyasi (Hermit) from early childhood itself, but his mother disapproved. Legend says that when he was about eight years old, he went with his mother to a river to bathe, where a crocodile caught him.

Shankara called out to his mother to permit him to become a Sanyasi, lest the crocodile would kill him. His mother had to agree, and the crocodile left him. Thus he took up Sanyasam, left home for education, and became a disciple of his Guru Govinda Bhagavatpada.

Through his extensive study of Vedas and Upanishads, propagating their true essence through his commentaries and discourses, he turned out to be a true genius reformer titled "Jagadguru." He got this title because of his efforts in resurrecting the ruining Indian religious tradition by reconciling the various sects (Shaivism, Vaishnavism and Shaktism) within his very short stint of just three decades. He attained moksha at Kedarnath. In 2019, the Indian PM unveiled a 12-foot statue in his memory.

Many more Indian poets spanning the first millennium of CE, contributed immensely to the vast library of Indian literature, most of who were lost to time, leaving only traces of their existence in the form of references in some of the surviving texts or inscriptions. The few that could be recovered have demonstrated the stunning mettle of Indian literature, capturing the attention of scholars worldwide. Many of the ancient works of Indian poets have been translated into almost all regional languages of India and many other foreign languages, particularly English, during the British regime in India

The period until the end of the first millennium belongs to Sanskrit poetry primarily though there have been some noted works in other Dravidian languages like Tamil in the form of "Cilappatikaram" by Ilango Adigal during the 2nd century CE and other languages like Telugu, Kannada etc. The second millennium was taken over by the flourishing poets from many other Indian languages and also saw the influence of foreign languages like the Persian Urdu brought in by the Islamic invasion and English imposed during British rule. These impositions added a new angle of beauty to the versatility of Indian poetry through some of its wonderful exponents waiting to be unveiled in the upcoming edition…

Read about Ancient Indian Education System.

Read the musings of a World-class Odissi dancer.

Read about an Indian painter painting his silence on the canvas.

Read about Hampi's Temple of Music.

DiscoveryourIndian'ness' throughthesilencethatreadingoffers.

Read our interview with the beloved author & social activist Mrs. Sudha Murty.

Read about Kalaripayattua martial art-form designed to develop harmony.

©Belraj Soni

©Belraj Soni

Hearing the sound of the alarm, Sujata’s husband said with a groan, “it is a holiday today; who set the alarm to go off.” While turning the alarm off, Sujata replied, “it’s your day off, not mine,” and got up to walk towards the kitchen.

She had woken up a little later than usual, as it was a Sunday and her kid’s school was closed. On today’s agenda was the making of Dahi Vada for the children. She had soaked the dal/lentils overnight and turned the mixer on to grind them, only to switch it off immediately, fearing that the sound of the mixer would wake the kids up, and her plan to surprise them with Dahi Vada for a Sunday breakfast would get spoiled.

The dal got her thinking about her childhood and how on school holidays, her mother would grind the lentils without her getting to know. There would be no noise, and she would sleep undisturbed, yet the dal would be ground into a fine, creamy paste.

She instantly remembered the Silbatta (Pestle and Mortar) kept in the corner of her mother’s kitchen. Her mother used to grind the dal using the Sil, a big rock which would act as the base and the Batta, another smaller rock used for applying pressure like a rolling pin.

Whenever her mother would grind something using the Silbatta, she would fondly remember Sujata’s grandfather and how he had carried the grinding stone it on his shoulders from their ancestral place to the new home where Sujata’s mother had gotten married and moved into.

A special place had been created for the Silbatta; after all, it had come from the maternal home of Sujata’s mother. The Silbatta did not look like any other inanimate object. One look at it, and you could feel that it was like a visiting relative. It was also not a lightweight or small Silbatta. The Sil was heavy, and the Batta had smoothened over time because of frequent use. This was an experienced Silbatta which, as per Sujata’s mother, was handed down to her by her mother, who had received it from her mother. One had heard of necklaces and bangles being part of the heirloom, but a Silbatta making it to the family heirloom was a first.

Anyhow, Sujata’s father had bought a mixer to give the Silbatta a run for its money. It had been kept close to the stove and next to the switchboard. Her father would turn the mixer on to vex his wife and say, "now we will hear its voice and not yours."

Her mother’s initial reaction to the mixer was one of delight. As she no longer would have to sit on the floor to use the Silbatta, neither would she have to wash this heavy rock of a grinder. At the click of a button, all the spices, dals and chutneys would be ground to the desired consistency.

The mixer had quickly dethroned the Silbatta, which got tucked away into a corner as the kitchen shelf made space for the mixer grinder. Not only did her mother's stares at the Silbatta reduce, but also the mention of her grandfather came down significantly, which pleased Sujata’s father a lot.

Alas, electricity was not ok seeing Sujata’s father be so happy, for there were frequent power outages. One day her mom got so fed up with this outage that she decided not to let her cooking be any longer dependent on the mixer or electricity. She took the appliance and kept it on the upper shelf, and with that, the ancestral Silbatta was brought back. As she washed the dirt off it, she proudly stated, “my father carried it here on his shoulders.”

Hearing this, Sujata and her father looked at each other, and Sujata’s brother proclaimed, “family Silbatta.” It was worth seeing the father's face as the relationship between the mother and the Silbatta strengthened again. The mixer gradually moved its way to the top shelf, where it was packed into the box in which it came.

At their home, a conversation started brewing about Sujata’s brother's marriage. Her brother insisted that Sujata be the first to get married, and her parents conceded, as the age difference between the siblings was merely two years. Sujata was the younger one, and her parents agreed. Within a few months, she got married, and with her husband, Rakesh, she moved to Delhi.

Sujata’s brother did not get married for some time as he prepared for the UPSC exam. As soon as he passed the exam, his parents fixed his marriage to a girl that he liked. Last month, Sujata went with her husband and children to attend her brother’s wedding. The Silbatta was kept in the same place in the kitchen where it always was. In the morning, Sujata’s mother, while grinding the spices, told her grandchildren with pride about how her grandfather had carried the Silbatta on his shoulders to this house. With this, the next generation also now knew about this heirloom.

The wedding happened smoothly and with wonderful simplicity. Only a handful of relatives who were close to the family had been invited, and within a few days, they left after giving their blessings. The house was again filled only with the family, and as the festivities died down, Sujata asked her mother, “will you make me the Dahi Vada tomorrow…”, the mother replied, “ I am exhausted, Sujata; it won’t be possible, for tomorrow.”

In the morning, everyone slept in late to get over the tiredness of hosting a wedding. Sujata was enjoying the warmth of the bed, only for the sound of the motor to wake her up. She stepped out of the room and realized that the sound was coming from the kitchen. As she entered the kitchen, she saw her sister-in-law grind the dal to fulfil her request and make an impression. Before saying anything, the parents and brother joined them, too and were peeking into the kitchen. Sujata's brother was looking at her; their father was looking at the mixer, their mom at the Silbatta, and the sister-in-law was looking at all of them.

The sister-in-law switched off the mixer and said she wanted to surprise Sujata but did not expect anyone to wake up. Her father, not paying attention to anything that was said, was lost in his happiness at seeing the mixer in operation again. After all, when he bought it, it was worth Rs. 2,000. Amid this warm and unexpected start to the day, Sujata felt that the Silbatta was looking at her mom and asking her not to keep it inside where it would be tucked into a dark corner. Her mother, on the other hand, was telling the Silbatta that both she and it had gotten old and they needed rest. Both she and the brother were waiting for their mother to say how her father had brought this on his shoulders to this home, but the mother did not say anything.

Just then, Sujata heard a voice, “Mom, what's in breakfast?” as the kids darted into the kitchen. Seeing the mixer and ground dal, the children got excited. Sujata stepped out from the memories with a strange discomfort. She could not focus on cooking one of the favourite breakfasts of her kids but instead kept hearing the Silbatta say to her, take me along with you, for this is our family tradition. Maybe, her brother was right when he said that this heirloom should stay with Sujata; after all, their mother got it from her mother, who got it from hers.

But where is the space to keep such a big and heavy Silbatta in today’s fancy kitchen – this thought preoccupied Sujata as she thought of her modern kitchen. Busy in this thought, she turned on the switch and brought the mixer to life. The mixer's sound drowned the voice of the Silbatta. The Dahi Vada was being prepared...

There are the usual suspects - regular workout, eat healthy, travel more - that many fall for only to end up forgetting them before.

We at Tarang have a better suggestion. No, we are not suggesting you read Tarang more - if you have gotten this far, then you already are doing it. So, how about contributing? Before you go, wait a minute I am no writer, we say that you are. Anybody who enjoys reading about our arts, culture and history is surely just a few words away from sharing that happiness. The world is parched for such happiness.

Okay, if you still persist you are no writer, we get that. In that case, you don't need any resolutions - you are perfect the way you are!

Tarang wishes you a great new year ahead spreading that joy and warmth that makes India truly incredible! And till we come back with our next edition, stay happy and smile on.

Founded in 2005 by Guru Violin Vasu and friends, the mission of Sanskriti Foundation is to promote Indian art, culture, and values by conducting training, workshops and an annual Tyagaraja Aradhana music festival. Foundation members benefit from meeting like-minded people, attending cultural seminars and attending bi-monthly concerts.

If you would like to learn more and become a member, you can reach us here: http://www.sanskritifoundation.in.

Venu Dorairaj Ramya Mudumba

Satyameet Singh

Dr. TLN Swamy (Advisor)

Dr. DVK Vasudevan (Advisor)