6 minute read

AM? IT’S WORTH IT

WORDS: Laura Griffiths

In 2018, I hopped on a plane to Atlanta, Georgia to judge a student competition that would see university teams put forward unique solutions for 3D printing in one of the industry’s most challenging materials, PEEK. Founded and hosted by chemical and materials specialist Solvay, the Additive Manufacturing Cup is designed to show how open-source innovation can lead to new additive manufacturing (AM) solutions, and from those coffee-colored tensile bars and Solvay logos I saw back at the Solvay offices over four years ago (that is one tough ‘S’ to 3D print), the competition has evolved into something that takes that innovation and applies it to realworld manufacturing scenarios.

For the 2021 edition, that included teaming up with cosmetics giant L’Oreal but of course, being 2021, it also meant less hopping on planes and more Zoom as I met the winners over video call along with collaborators Solvay, L’Oreal and Ultimaker. Suddenly, my usual routine of applying L’Oreal face cleanser and True Match foundation that morning, had found a nice new layer of meaning.

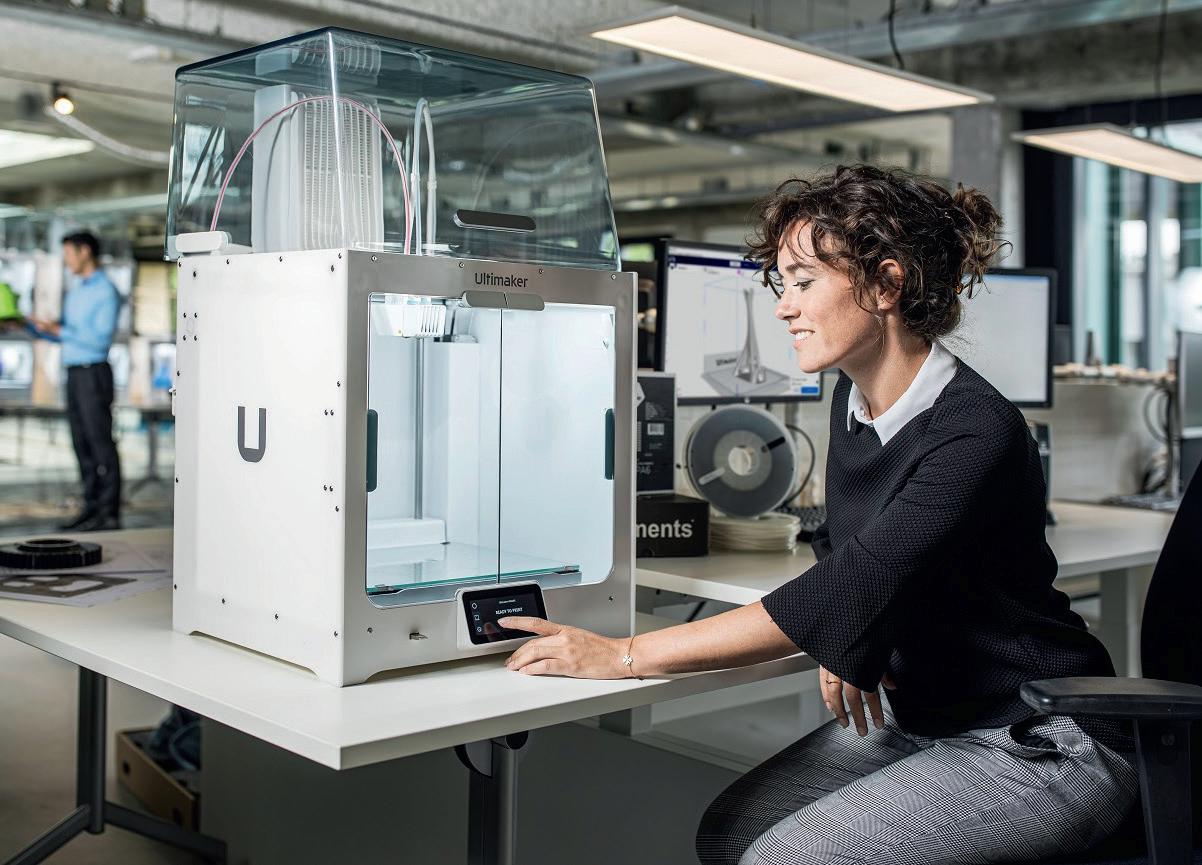

For the competition’s third edition, 60 international teams were tasked with putting forward a real-word industrial application that could transform production line agility using Solvay’s Solef PVDF AM filament, a highly nonreactive thermoplastic fluoropolymer that’s inherently flame retardant. It’s not the most glamorous of applications for a company that specializes in beauty products but the benefits of 3D printing for applications along manufacturing lines cannot be understated. Often the unsung 3D printing heroes of the production floor, Ultimaker’s polymer extrusion-based technology, for example, has been put to work at major brands like Volkswagen and Heineken, where the latter was able to reduce production costs of a manufacturing tool by 70% compared to traditional methods. In addition to printing the designs directly on one of its S5 desktop printers, the competition leveraged Ultimaker’s renowned materials ecosystem and optimized Solvay material profiles to create the winning parts.

“The real advantage of having an open platform is the ability to bring in the expertise, the real skill sets and the advantages of others in the ecosystem onto the platform to deliver that tailored solution for our users,” Miguel Calvo, CTO at Ultimaker said of the company’s role in the competition. “Put simply, it's leveraging the expertise around the ecosystem, bringing them into the platform so that we can deliver a greater, wider spread of applications to our users. This challenge perfectly highlights that.”

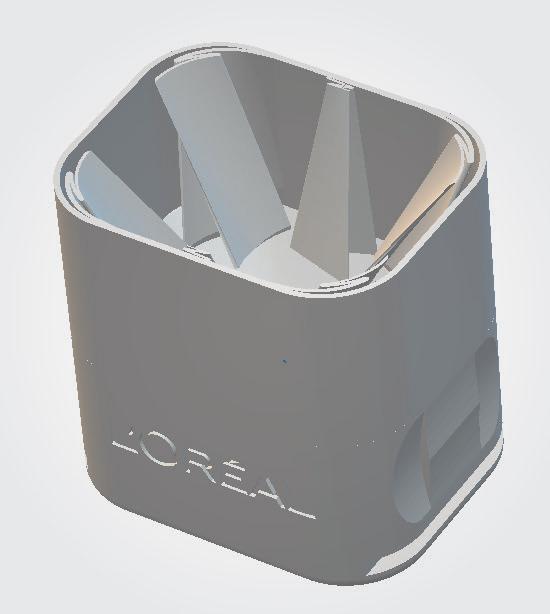

3D Fab from the University of Lyon, France took home first prize with a versatile monobloc design that could be used on a packaging line to hold unstable products in place. The design is based on a reversible deformable puck that can be printed quickly and easily and applied to a number of different product types: think mascara tubes or tall shampoo bottles which are transported around a production line at high speed.

“They have invented a solution that basically can work for all the bottles and not only for the five that L'Oreal assigned as a benchmark so you don't have to reprocess again in case you have a different type of bottle,” said Andrea Gasperini, Business Development Manager at Ultimaker, of the winning design. But there are other advantages too, including noise cancellation: “There's a lot of noise because we have 400 pucks moving around and touching each other all the time but here, the bottle was really firm. The bottle is not allowed to move at all because every movement outside of the pack would imply a spill or a defected product that needs to be removed somehow before it gets packed.”

Matthew Forrester, Head of Material Transformation & Recycling Science at L’Oréal, an engineer by trade, knows firsthand what is expected from this kind of application having grown up working on

SHOWN:

AGILE MANUFACTURING USED FOR LIPSTICK MANUFACTURE WITHIN ONE OF L’ORÉAL’S PRODUCTION FACILITIES (CREDIT: L’ORÉAL)

SHOWN:

DESIGN BASED ON A REVERSIBLE DEFORMABLE PUCK WHICH CAN BE APPLIED TO VARIOUS PRODUCTS ON A PRODUCTION LINE.

SHOWN:

WINNING DESIGN BY 3D FAB LYON.

these types of engineering challenges. Today, those challenges include considerations around the environmental impact at every stage of the supply chain from the fi lling plants to the hands of consumers who want their products quicker than ever before.

“They want them yesterday,” Forrester said. “As soon as you click on the Amazon button, you want the part to be at your door, which obviously means that we need to have the industrial tools which are capable of replying as quickly as this. So being able to quickly change between products, being able to ramp up production, slow down production, move production between countries produced locally to reduce transportation, these are the kinds of challenges that engineers are having, and this is exactly what we wanted to share with the participants by opening up a window into our industrial processes.”

The winners have spoken about their excitement around developing a realworld solution that could be deployed on a production line like L'Oréal's. As part of a prize, which also included fi ve thousand Euros to be reinvested in academic, societal or entrepreneurial activities and an Ultimaker 2+ Connect printer, the team were taken on a guided tour of a L’Oreal mass market manufacturing site and luxury products manufacturing site where they were able to put their pucks on the line. While L’Oreal sites have been equipped with FDM 3D printing for the last four years, in some cases just meters away from the production line, the collaborators have been impressed by the ideas the teams were able to think up.

“What we need to bear in mind is that these guys have never seen a L'Oreal production line,” Forrester said. “They've managed to produce these solutions without really knowing the environment in which they're going to be working on. They're not plug and play solutions. We can’t just throw it straight onto the production line but what they have come up with is diff erent solutions which can inspire our teams, and we can integrate some of their ideas and ways of thinking as well which is just as important as the fi nished product.”

Forrester shares one example from a runner up team where a simple rubber band was used as an eff ective alternative in place of a calibrated rubber strip, typically used for sound deadening. It might not be the most revolutionary concept but sometimes, the simplest ideas can be the most functional. Forrester continued: “I think the idea of having a clean sheet and not being formatted by working in a certain environment allows you to think outside of the box.”

In fact, Brian Alexander, AM Global Product & Application Manager at Solvay, remarked how the winning parts were able to “virtually match the performance and quality” of their conventional injection molded equivalent, affi rming not only the success of the winning team but also the growing potential for accessible 3D printing technologies in industrial settings.

Calvo added: “The students and the young professionals have really picked up on the fact that you can now design for process in a way that you couldn't before. 3D printing unlocks geometries that would be impossible to produce in small quantities in prototypes in the past, and the winning project is a very good example of that with these conformal fi ns – I'm not sure how you prototype those without the use of some kind of 3D printing. They really did take to heart the fact that they were designing functional products, functional parts. It really unlocked their ability to be creative and innovative because they weren't shackled by traditional manufacturing methods. It was nice to see people outside of the 3D printing industry really leveraging the abilities of this technology to unlock their design, innovation and design freedom.”

SHOWN:

ULTIMAKER S5 USED TO 3D PRINT WINNING DESIGNS (CREDIT: ULTIMAKER)