and

In this module we will look at phonology and pronunciation and their ef fects on verbal communication.

First, we will review the English language phonemic alphabet as defined by the IPA, the International Phonetic Alphabet. We will also compare the ways in which sounds are physically made.

Second, we will study the effects of stress, rhythm and intonation on perceived spoken language.

Finally, we will consider the ways to effectively introduce and integrate phonology into the classroom.

The format of this module differs to previous modules due to the fact that the information is restricted to one description of phonetics (the IPA) and therefore comparative analysis is not required.

All the phonetic script seen in this module was generated using Jan Mulder's ‘Phonmap’ program. The program makers charge for the latest version, but you can download an earlier free version here: .www.teflserver.net/diprscs/phonmap300.exe

Select “save” or “save to disc” when prompted.

Alternatively, there’s an excellent online phonetic script keyboard here: http://ipa.typeit.org

Linguistics is the scientific study of a language, either theoretical or applied. Theoretical linguistics involve a number of sub-categories including structure (grammar) and usage (semantics). Within the study of grammar, there are also the aspects of morphology, the formation and alteration of words, and syntax, the rules that define the ways in which words combine to create meaningful phrases.

Phonology is yet another sub-category This can be defined as the study, science, analysis and classification of speech sounds, or the sound system of a language. Phonology also includes phonetics, the physical properties and perception of speech sounds. Applied linguistics puts theoretical linguistics into practice, and these are the applications used in foreign language education and second language learning.

The most obvious aspect of phonology is the list of distinctive units within a language. More specifically, phonemes are individual speech sounds and the symbols used to represent these sounds. For example, while the sounds represented by / d / and / t / are unique speech sounds, their physical properties are similar. The usage of vocal chords to create the / d / sound highlights the differences in meaning between the words ten and den, even though these words differ by one subtle sound. In addition to phonemes, phonology also includes the ways in which stress and intonation affect perception in verbal communication.

Ideally, the letters used in a language's written alphabet would also represent their individual speech sounds. The idea being that anything written can be read aloud and pronounced effectively. For many languages, such as Korean or Thai, this is the case; every character represents a written letter and a corresponding sound, with no overlap. In contrast, in English, while the words rude and food look different, they sound similar, unlike the words tough and cough, which look similar but sound different.

Teaching the English language effectively therefore requires two alphabets. There is the orthographic alphabet, the modern written alphabet (or the traditional ABCs), and a phonemic alphabet, used to categorize and represent the speech sounds involved in the English language.

Generally speaking, the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) is a universal phonemic alphabet used to organize and represent speech sounds of any language. While there are many schools of thought on the variations of sounds, the IPA concludes that there are a total of 44 basic sounds used in most variations of the English language. More on the IPA at www.internationalphoneticassociation.org

You may then ask yourself, how are there only 26 letters in the English orthographic alphabet and a total of 44 sounds? The answer to this is simple – the individual written consonants and vowels are combined by speech patterns to create the 24 consonants, 12 vowels and 8 diphthongs that make up the phonemic alphabet. Although we write out words using individual letters, the way we speak combines these units to create a wider range of communicable sounds.

International ITEFL nternational TEFL

International ITEFL nternational TEFL

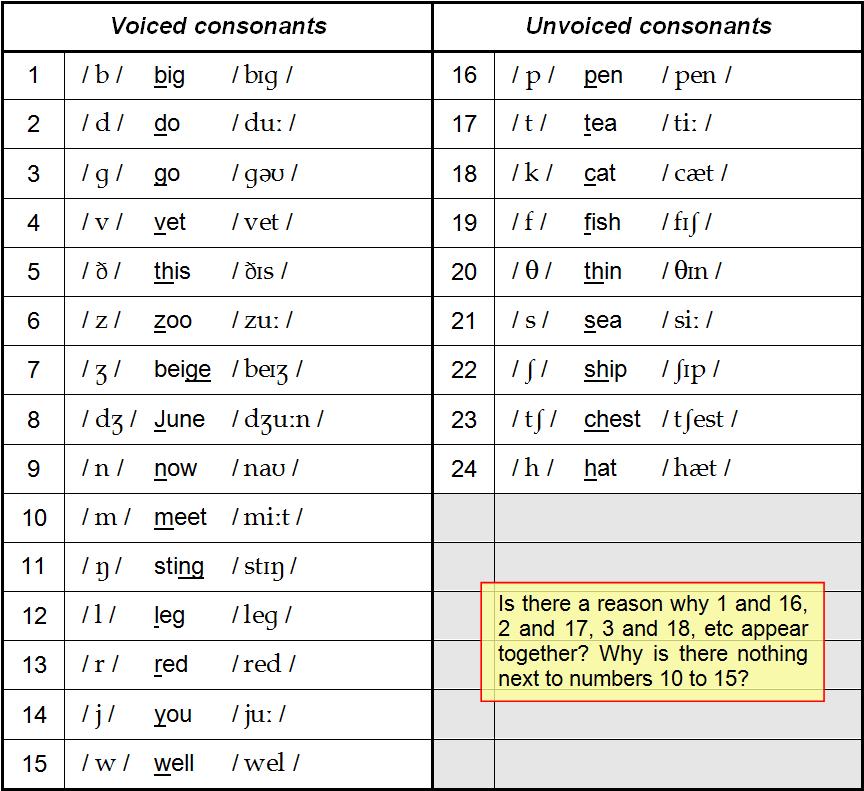

Let's take a look at the 44 sounds used in the English language. The slash marks, / /, work like parentheses to indicate that the contents between slashes are symbols representative of speech sounds (phonemes), rather than orthographic letters. Though a total of 24 consonants exist in the spoken English language, this category can be broken down further into 15 voiced consonants and 9 unvoiced consonants.

A voiced consonant refers to the usage of vocal chord vibrations to create a consonant. For instance, hold your hand up to your throat and pronounce the “z” in zoo. You should be able to feel your throat vibrating softly.

An unvoiced consonant lacks the usage of vibrations in your throat to create a speech sound. Now, pronounce the “s” in sea. You should be able to feel the difference, with no vibrations coming from your vocal chords when you say the “s” sound.

Here is the total list of consonants broken into voiced and unvoiced groups. You will find an example of a word that uses the consonant and the complete phonetic spelling of that word as well. And just like letters that are combined on paper to create written words, the phonemic symbols are put together in ways to create spoken words.

Hold your hand up to your throat and practice saying these sounds:

There are a total of twelve vowels in the English language. The colon (:) next to the first 5 vowels listed (numbers 25 to 29) indicates a long vowel, meaning that these sounds are held out longer than the others. The other 7 vowels (numbers 30 to 36) are short.

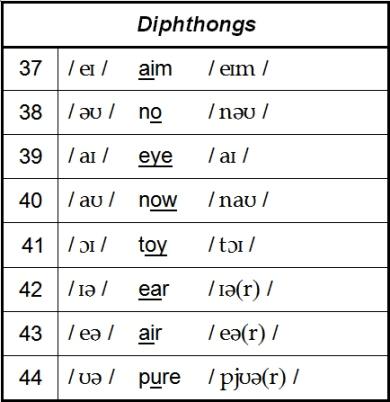

Diphthongs are the combinations of two vowels. More specifically, each sound begins with one vowel and ends in another There are 8 diphthongs in the English language.

English is obviously an incredibly widely-spoken language. With different countries and regions within these countries using different accents and dialects, it may seem difficult to understand how there can be one uniform phonetic alphabet, but there is a relatively straightforward answer

Just as pronunciation differs from one person to the next, so will their phonemic spellings. Unlike a uniform written spelling of a word in English, there is no uniform way to say a word. For example, if you compare a British dictionary to an American dictionary, you will quickly see a difference in pronunciation.

Look at the following examples:

You'll see that a British clerk is an American clock, and marry, merry and Mary are indistinguishable from each other in American English.

Phonology also includes the area of phonetics, or the physical properties of sound production. By familiarizing yourself with the study of articulation (the physical attributes and manner of sounds), you can effectively teach your students how to create new sounds.

To clarify, not every language uses the same sounds and this can make pronunciation very tricky. For example, if you were a right-handed person and someone suddenly asked you to write with your left hand, you would find this awkward and difficult. With time and practice, you could be a proficient left-handed writer by practicing the physical movements necessary to write legibly The same is true for pronunciation.

n Why do Germans have problems with the / v / sound?

n Why do French speakers have problems with the / ¶ / sound?

n Why do the Japanese have problems with the / r / sound?

n Why do Koreans have problems with the / f / sound?

Add three more to the list:

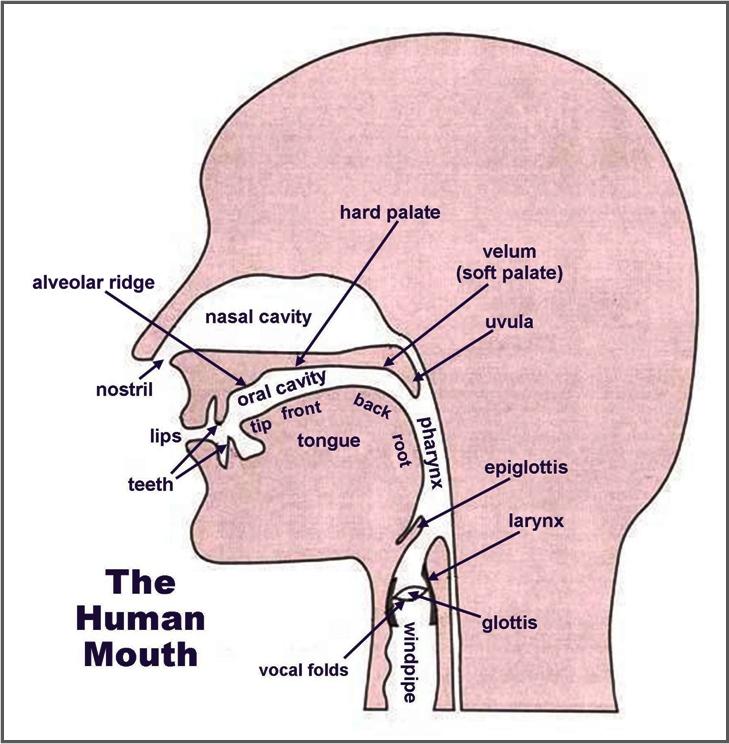

Articulatory phonetics is defined as the placement of sound production for consonant sounds. This means the way in which your mouth is shaped to create a sound.

For example, when you say the / t / sound, you will feel the tip of the tongue make contact with the bony ridge behind your top teeth (the alveola). Once you force air through your mouth, your tongue comes down while simultaneously releasing the / t / sound. This is called an alveolar consonant

The diagram below illustrates the specific areas in your mouth and the terms used to describe articulatory placement.

The soft palate is the back muscular portion of the roof of your mouth, also known as the velum. When the back of the tongue (known as the dorsum) is raised and strikes the velum, velar consonants are produced. Keep in mind that the velum is a wide area and the movements of the dorsum are not very precise. Depending on the speaker and/or on the vowel or diphthong sounds surrounding the velar consonant, the placement may change slightly or even undergo assimilation in which a velar consonant may become a palatovelar consonant. The velar consonants are: / k / as in cat, / ý / as in go, and / ÷ / as in sing.

Palatal consonants are produced when the body or central part of the tongue is raised against the hard palate, which is the middle part of the bony section of the roof of your mouth. The palatal sounds are: / ½ / as in vision, / § / as in ship, and / j / as in yes.

The alveolar ridge is the bony area just behind the top teeth. An alveolar consonant is made when the front or tip of the tongue is raised to or touches this ridge. The alveolar sounds are: / t / as in ten, / d / as in do, / s / as in sit, / z / as in zip, / d½ / as in jump, / t§ / as in chest, / n / as in now, / l / as in let, and / r / as in red.

A dental sound refers to a sound that is made when the tongue comes between the teeth. Again, keep in mind that the degree to which the tongue touches both sets of teeth is dependent on the speaker The dental consonants are: /¶ / as in the, and / / as in thin.

Predictably, a dental sound refers to the usage of teeth. A “labio” sound refers to the usage of lips to create a sound. There are two labio-dental sounds in the English language and both require that the bottom lip comes into contact with the top teeth. The labio-dental consonants are: / v / as in vet, and / f / as in feet.

If “bi” means two, you can probably deduce what a bilabial consonant requires for sound production. If you guessed that bilabial sounds are produced when both lips come together, you were correct. The bilabial sounds are: / b / as in boy, / p / as in pen, / m / as in meet, and / w / as in will.

The opening at the upper part of the vocal chords is called the glottis. In English, a glottal sound is produced when air is restricted at the opening of the vocal chords. The glottal consonant is / h / as in hat.

Manner of articulation can be described as the way consonants are produced, i.e. the ways in which speech organs make contact to produce a sound.

For example, unvoiced consonants do not involve vocal chord vibrations. Instead, air is released in a systematic way. Put your hand up to your mouth and try saying the / t / sound. How is the air released? Is it forceful or slow? Now, say the / d / sound. Did you notice any differences? Both sounds have a plosive manner; however the / t / is unvoiced and the / d / sound is voiced. The manner is therefore different for the two sounds, but the mouth placement is identical for both.

The following terms are used to describe manner of articulation:

When a plosive consonant is made, there is a complete blockage of both the oral and nasal cavities in which no air can be released. When the blockage is cleared (e.g. tongue is lowered or lips open), the sound is forcefully released, like an explosion. The / p /, / ý /, and / d / sounds are examples.

Like a plosive consonant, there is still a blockage present, but when a fricative consonant is made air is still forced through the vocal tract. The / § /, / z /, / /, / v /, and / h / sounds are examples.

An affricate consonant begins like a plosive consonant with a complete blockage of air flow. However, once air is released the blockage is not cleared, and the air is released like a fricative consonant. The two affricate sounds are /d½ / and / t§ /.

A nasal consonant is produced when the velum is lowered, allowing air to escape through the nose. The oral cavity acts as a resonance chamber though air does not escape through the mouth. The three nasal sounds are: / m /, / n / and /÷ /.

Approximant consonants are intermediates between vowels and consonants. The articulatory features include a constriction of the vocal tract with enough space for air to flow through. These sounds are more open than fricatives. These are the three types:

Semi-vowels are briefer and not as constant in structure as the other consonants. For example, if you hold out the sounds / j / as in yes and / w / as in wet, you can very easily hear similarities to vowel sounds.

A lateral consonant refers to the / l / sound as in letter This refers to the placement in which the tip of the tongue comes into contact with the alveolar ridge or the top teeth. Unlike alveolar and dental consonants however, air from the lungs escapes around the side of the tongue rather than over the top of the tongue. Strictly speaking, the lateral quality is not really a placement of articulation but more of a combination between placement and manner properties of the consonants.

There is one alveolar approximant in English. This is the / r / sound as in the word red. The tip of the tongue is raised to the bony ridge behind the top teeth like an alveolar consonant. However, unlike other alveolar consonants, there is a constant airflow through the vocal tract and over the tongue.

The chart represents the combinations for placement and manner Note that when sounds appear in pairs, one is voiced and the other unvoiced. Can you identify which is which?

Once you’ve studied the chart below, look again at the question in the page 3 table yellow box. Is it now easier to answer?

For more practice with the IPA, mouth placement and manner, take a look at these websites: http://smu-facweb.smu.ca/~s0949176/sammy/ www.teachingenglish.org.uk/article/phonemic-chart

You can download the chart (which includes sample sounds and words) from the British Council website above to use on your PC by clicking Note that this only works on a Windows computer, and uses Adobe Flash Playerhere

Bear in mind that the IPA is designed for a multitude of languages, so many of the sounds that are possible to represent with the tools at these websites simply don't exist in English, and are therefore not included in this module.

In phonetics, consonants can be characterized by a closure or constriction of the vocal tract at one or more points above the glottis (the opening to the vocal chords). A vowel, on the other hand, is characterized by the opening of the vocal tract so that there is no build up of air pressure.

The articulatory features used to distinguish vowels describe common pronunciation features. For the English language these consist of height (the vertical, or the up and down dimension of the tongue in relation to the roof of the mouth or the aperture of the jaw), backness (the horizontal, or the forward and backward dimension of the tongue in relation to the back of the mouth) and roundness (the shaping of the lips).

A close vowel is made when your tongue is raised as close to the roof of the mouth as possible without making a constriction. Close vowels are often called high vowels because the tongue is raised high in the mouth during articulation. For example, the / iÉ�/ sound in tea, and the / uÉ / sound in blue.

A half-close vowel is similarly positioned to a close vowel but is less constricted. Half-close vowels are sometimes called lax variants of close vowels. For example, / ö / as in sit and / ¬ / as in book

A mid vowel is positioned halfway between a close vowel and an open vowel. For example, the / W / in ago.

An open-mid vowel is made when the tongue is positioned halfway between an open vowel and mid vowel. For example, / ±É / as in bird, (/ b±É(r)d /) / à / as in but, and / ¿É / as in for (/ f¿É(r) /).

·A near-open vowel is similarly positioned to an open vowel but it is slightly more constricted. Near-open vowels are sometimes called lax variants of open vowels. For example, the / ¾ / sound in cat.

An open vowel is a vowel sound made when the tongue is positioned as far as possible from the roof of the mouth. Open vowels are sometimes called low vowels. For example, the / ΃ / sound in spa, and the / / sound in pot.

A front vowel requires that the tongue is positioned as close to the front of the mouth as possible without making a constriction. For example, the / iÉ / as in sheet, the / e / sound in get, and the / ¾ / sound in bat.

A near-front vowel is made when the tongue is positioned similarly to a front vowel but slightly further back in the mouth. For example, / ö / as in fit.

A central vowel is when the tongue is positioned halfway between the front of the mouth (front vowel) and the back of the mouth (back vowel). For example, the / W / in about and the / ±É / sound in word (/ w±É(r)d /).

A near-back vowel is positioned similarly to a back vowel but is slightly more forward in the mouth. For example, / ¬ / as in put.

A back vowel is created when the tongue is positioned 'out of the way'; as far back in the mouth as possible without creating a constriction. For example, / uÉ / as in boot, / à / as in up, / ¿É / as in saw, / ŒÉ / as in father, and / / as in hot.

Roundness refers to whether the lips are rounded or unrounded. Like all mouth placements, the degree of this will differ from person to person.

Take a look at the vowel descriptions below:

Diphthongs can be defined as the combination of two vowels. The sound begins with one vowel and ends in another More specifically, the unstressed vowel can be described as a semi-vowel but the whole sound is considered one phoneme.

Take a look at the diphthong descriptions below

In written English, we use punctuation to signal emphasis and to direct the speed at which a reader moves through a text. In spoken English, we use groups of sounds (syllables) to affect the message given. These effects are known as suprasegmentals, or prosodic features, and include, stress, rhythm and intonation.

Let's consider the effects of stress on pronunciation.

The pronunciation of a word consists of at least one syllable and if an English word consists of more than one syllable, at least one syllable will sound more prominent than the others.

Stress can be defined as the relative emphasis given to a specific syllable of a word, and this differs from one language to the next. In the English language, stress refers to the loudness (intensity), and the duration (changes in pitch and frequency) of a pronounced syllable versus an unstressed syllable which is softer and less pronounced.

It is commonly believed that there are two types of stress in the English language: primary stress and secondary stress. Primary stress is the strongest degree of stress placed on a syllable in the pronunciation of a word and is often marked by this symbol ( Ç ). Secondary stress refers to the degree of stress given to much weaker syllables and used with longer words. Secondary stress is sometimes indicated by this symbol ( È ). Examples might be the words counterfoil (/ Çka¬ntWÈf¿öl /) and counterintelligence ( /Èka¬ntWrönÇtelöd½Wns/�). Note that unstressed syllables have no stress marks.

Some linguists argue that stress should even be described as having four levels, primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary, but these levels can often disagree with each other, so are seldom referred to in TESOL situations.

English is also a lexical language, in which stress cannot be arbitrarily given but rather it is assigned to and gives meaning to the word and must be learned. This means that two words can be spelled the same but differ only by the position of the stress on a particular syllable (defined as homographs). For example, compare the pronunciations of the verb, to record, and the noun, a record. The verb, to record, is stressed on the last syllable, to record, and the noun, a record, is stressed on the first syllable.

However, there are a few common rules used to correctly assign stress, making the concept easier to understand and apply.

Firstly, a word in English can only have one stress. As previously mentioned, secondary stress can be used to indicate lesser stressed syllables, but there can only be one primary stressed syllable in a word.

Secondly, only syllables can be stressed and not individual vowels or consonants.

The following are guidelines rather than set rules for determining stress. An English speaker should try to hear the music of the language and apply the stress as appropriate to the rhythm of speech. The stress is underlined, for clarity.

In context, stress is also used to indicate the meaning of a sentence. We use stress to highlight attitudes and feelings such as excitement, disappointment, boredom, interest, pride, indifference, warmth, hostility, regret, hope, disbelief, happiness; the list goes on.

As an example, in each of the following sentences a different word is stressed to imply a different meaning or implication:

1. John didn't mean to kick that dog. (the speaker believes that a different person kicked that dog)

2. John didn't mean to kick that dog. (the speaker is challenging someone who believes John meant to kick the dog)

3. John didn't mean to kick that dog. (John accidentally kicked that dog)

John didn't mean to kick that dog. (John meant to do something different to that dog)

John didn't mean to kick that dog. (John meant to kick another dog)

John didn't mean to kick that dog. (John meant to kick something else)

However, there is more to stress than individual words. In normal speech, there are more syllables without stress (unstressed) than with stress.

At this point, you should be aware that the English language is characterized as a stress-timed language, meaning that stressed syllables occur at a roughly constant rate and non-stressed syllables are shortened to accommodate this. Syllables may last different amounts of time, but there is an average between two consecutive stressed syllables and this time is generally constant. In English, the faster we speak, the more vowels are shortened or dropped. This allows for more syllables to be used without changing the rhythm, or musicality of speech.

Rhythm is the pattern created by the combination of stress and intonation. Like in music, all speech has rhythm but we are unlikely to hear or notice regular or repeating patterns like we do when listening to music, rhymes or chants.

For example, take a look at the two sentences below:

The beautiful mountain was illuminated in the distance. (a total of 16 syllables)

He can come on Sunday as long as he doesn't have to do any homework in the evening. (22 syllables)

Although there are more words and more syllables in the second sentence, both sentences take approximately the same amount of time to say because of the number of stressed words in each. The reason being, English speakers do not pronounce and stress every word clearly in order to be understood. Instead, English speakers focus on maintaining a particular rhythm of speech while conveying a message and, accordingly, stressing these words clearly

This leads us to another question, which words are usually stressed and which words are usually unstressed? Again, keep in mind that there are always exceptions to the rule.

words are generally stressed:

main verbs

negative auxiliary verbs

words are generally unstressed:

positive auxiliary verbs

prepositions

Take a look at the sentence below:

He's gone to the supermarket with his friend.

The first syllable in supermarket has primary stress while there is secondary stress on the third syllable.

As a rough rule, the stressed syllables of any sentence are the words conveying essential information in the sentence (what – action, where to, and with who).

To maintain a particular rhythm, English speakers often economize their speech by trying to reduce the number of syllables said. In English, there are four major ways that sounds join together.

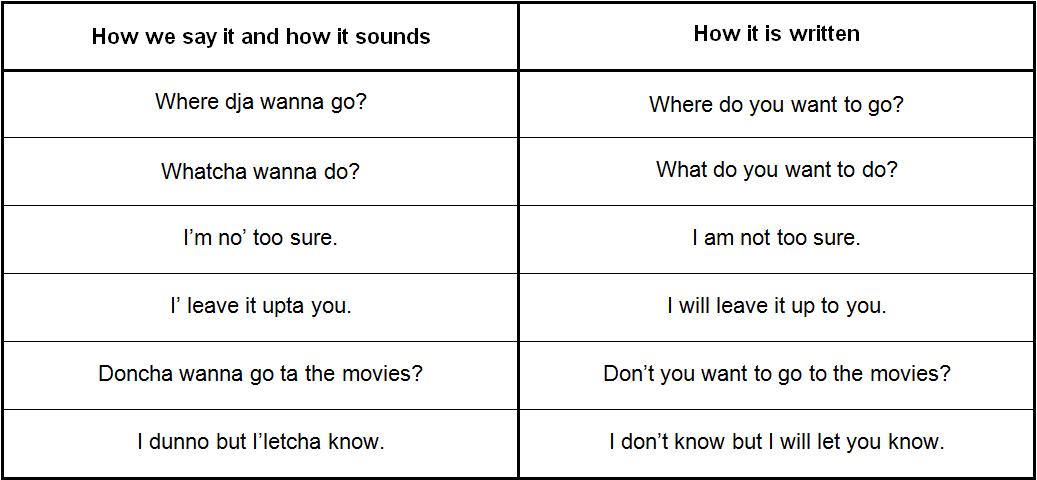

Sound joining particularly comes out in conversation as English speakers speak quickly to maintain a particular rhythm. Below are more examples, most of which transcend regional variations:

Whereas stress is more concerned with individual words, intonation is the variation of volume and pitch of a whole sentence. It is particularly important in questioning, agreeing, disagreeing or confirming statements.

1. The first pattern of intonation is the rise/fall pattern of intonation. This can be described as a general rise in pitch then a lowering in pitch to the original tone or frequently lower For example:

I haven't seen him for a week.

1a. This type of rising and falling intonation is used to indicate that you have finished what you wanted to say for positive and negative statements (e.g. “This book is fascinating.”, “I didn't receive it.”), greetings (e.g. “Hello.”, “See you later.”) and instructions (“Sit down.”).

I'll see you at six, then. (There is nothing more to be said.)

1b. The same rule applies to short utterances as used when agreeing.

1c. A third usage of the rise/fall intonation is the pattern used for straightforward questions. This indicates that the speaker has finished what he wants to say and a reply is left up to the listener

Where did you buy it?

2. The second most common intonation pattern is the fall/rise pattern.

2a. The fall/rise pattern often indicates surprise disagreement, but most importantly, the speaker wants the person to whom he/she is speaking to respond or confirm.

You don't really mean that, do you?

The gradual rise to “mean”, then fall and rise to “do you” may be a surprised feeling, but certainly needs confirmation.

2b. The same pattern can also indicate that the speaker hasn't finished what he or she has to say

I was in the market the other day…

The fall/rise to “day” denotes don't speak yet, I'm not finished.

Similarly if the speaker were to continue:,

And do you know who I saw?

conveys the message, I don't want you to answer

3. Finally, there is a kind of level intonation which is basically flat. This often indicates that the speaker does not have much to say and perhaps doesn't want to communicate. Common instances are normally short ones like:

Carry on.

I understand.

Generally, when you finish what you want to say, the intonation falls – in positive and negative statements, questions, greetings, and instructions. If the person being addressed wants to reply, they can; it's up to them.

As in the following:

This book is fascinating. Where did you buy it?

I didn't. (pauses and decides to give more detail)

It was given to me.

Hi! Hello! How you doing? Have a nice day. Good morning! Have fun! Sit down. And keep quiet. Enjoy your meal. Please shut the door

Say the above to yourself. You should find that ALL the above examples have falling intonation since you (the speaker) intend to say no more.

To summarize the three patterns, three different ways of answering the phone might serve as an example:

Hello! indicating “please speak. It's your turn.” Polite and welcoming.

Hello! indicating that the speaker has finished what he wants to say and is generally not very happy with the situation! (Perhaps this is the sixth call in ten minutes!)

Hello! Not very welcoming, but perhaps grudgingly allowing the caller to speak.

©

1 One of the biggest concerns for practicing teachers is the way to address the pronunciation differences in the English language, particularly British and American English. There are not only obvious pronunciation differences, but also differences in grammar rules and spelling.

Which phonemes, with examples given, differ the most between dialects? How would you approach these issues in the classroom and why?

2. Can correct pronunciation be taught without using the phonemic alphabet? How? What are the problems of excluding the phonemic alphabet? What are the benefits of using a phonemic alphabet?

3. Teaching phonology and correct pronunciation is often approached as a separate entity. There are grammar, vocabulary, reading, writing, listening, speaking and phonetics. While some teachers prefer to teach phonetics separately, others prefer to integrate phonetics into their lessons.

a. Design an hour-long ESA lesson focused solely on pronunciation. Include examples of board work, elicitation and materials (exercises and activities) you would use in this lesson.

b. Also, design an hour-long ESA lesson in which phonetics is integrated into another lesson. Include examples of board work, elicitation and materials (exercises and activities) you would use in this lesson.

Keep in mind that you do not need to include every phonemic symbol and sound. Instead you can compare and contrast similar sounds or groups of sounds.

4. Jose A Mompean argues that an Integrated Pronunciation Teaching (IPT) approach is more effective than teaching phonology in isolation. Search for his article entitled “Taking Advantage of Phonetic Symbols in the Foreign Language Classroom” and read it in full.

List the advantages and strategies for introducing and integrating phonetics into the classroom.

Which approach do you find most effective? Why?

5. Phonetics can be used in every type of lesson. Consider phonetics, stress and intonation and describe teaching techniques, exercises and activities that are applicable for the following.

To get started, you may want to take a look at this site: https://study.com/academy/lesson/teaching-strategies-for-phonological-phonemic-skills.html

1 Transcriptions:

1a.

the

from

script

script.

1b. Transcribe the following passage from

script to orthographic script.

/�¶W� st¾nd±Érd� flöp� t§ŒÉrt� (mŒÉd¬l� eöt� faöv� ziÉrW¬� ziÉrW¬� riÉ� f¿Ér)� öz� W� waöt� pl¾stök� kW¬ted b¿Érd� wö¶� W� ýreö� met¬l� freöm� ¶W� peöp±Ér� p¾d� öz� held� f±ÉrmliÉ� ön� pleös� wö¶� tuÉ� m¾ýnetök�� nbz¾nd� k¾n� biÉ� Wd½Ãsted� tuÉ� WkŒÉmWdeöt�veWriÉÃs� kWm±Ér§¬l�saözez� ¶ös� mŒÉd¬l� kÃmz�� kÃmpliÉt� wö¶� W� keWröj÷� h¾ndWl� iÉz¬l� ¾nd� W� rWmuÉvWb¬l� WluÉmönÃm�pen�treö� wWt�W�plezönt��

ŒÉlt±Érnötöv� tuÉ� ¶W� spaörÃl�ba¬nd� daönW¬s¿Érz� Ãv� ¶W� p¾st� sÃd½estöd�riÉteöl�praös�twentiÉ�� sevWn�dl±Érz��sökstiÉ��naön�sents�/

1c. Transcribe the following conversation from phonemic script to orthographic script.

h¾nW� W¬�� ösöz���sW¬��Wn¿öjiÉ÷��weWrŒÉn±É ��dödaö��p¬t��maö��kŒÉrkiÉz

d½eösWn� kWmŒÉn��nŒÉtWýen��h¾vjW��l¬ktŒÉn¶W��köt§ön��teöbWl

h¾nW� aöv��l¬kt��evriÉweWr��ýŒÉn�� ruÉ��evriÉ iÉ÷��aöm��sW¬��frÃstreötöd

d½eösWn� swiÉthŒÉrt��j±ÉrhW¬plös��ha¬meniÉ��taömz��h¾vjuÉ��dWn ös

h¾nW� eönks��f±Ér��remaöndiÉnmiÉ��aö��sWpW¬z��öts��tuÉmÃt§��trÃbWl�� f±ÉrjuÉduÉ��help��miÉ��faöndWm��W¬��l¬k��¶eWr¶eöŒÉr��Ãnd±Ér¶W�� nuÉzpeöp±Ér

d½eösWn� wel��¶¾t��d½Ãst��ýW¬z��tuÉ��§W¬juÉ��wWtjW��niÉdöz��sÃm�kaöndW�� söstWm��f¿Ér��weWrjuÉ��p¬t�� iÉ÷z��juÉ��luÉz��sÃm iÉ÷��evriÉdeö��öts�� ¾bsW¬luÉtliÉ��rödökjuÉlWs

h¾nW�

d½eösWn�

j±ÉrwÃntWtŒÉk��öt��wWz��juÉ��huÉ��lŒÉst��¶eWr��kredötkŒÉrd��¶Wà ±Ér�� deö��¾nd��aö��fa¬ndöt

j¾��aönW¬��j±Éraöt��¾ndaöm��ekstriÉmliÉ��ýreötfWl��bÃt��juÉ��§¬d��ýetöt�� tWýe¶±Ér��¾nd��¿ÉrýWnaöz��j±Érself

3. Say each of the following sentences and underline the unstressed syllables in each:

3a. Once upon a time, there was a young girl.

3b. In light of the above statement, I shall abstain from voting.

3c. Good morning. How can I help you?

3d. I'm away for the rest of the week

4. Indicate the major ways in which English sounds are joined and linked. Give two of your own examples for each.

5. For each of the following sentences, give the meanings indicated by: i) the rise/fall intonation pattern ii) the fall/rise intonation pattern

5a. I'm not going to tell you the gossip. i) ii)

5b. She's not going out tonight, is she?

5c. I don't understand.

5d. Goodnight.

6. How and why can a student's pronunciation affect the quality of his/her communication?

You should now be ready to access the test.

Make sure you have copied and saved a file of your guided study and research answers, so that you can refer to them during the test.

Good luck.