E te rangatira, te pītau whakarei o te Te Papa Tongarewa, haere, haere, haere atu rā. Te murau o te tini, te wenerau o te mano, te kaipūpuri i te whao, te tohunga toi Māori, te tōtara haemata o te wao nui a Tāne kei te mōteatea tonu te iwi Māori i tō rironga atu. Ko koe te pou matua o Te Papa Tongarewa i ngana, i ārahi haere ngā mahi kia tū tōtika te whare. Haunga noa ko to marae o Rongomaraeroa me te tipua kei runga a Māui Tikitiki-a-Taranga. Kua ripia kua haehaea mai te tau o te ate, ā, kei te hotuhotu tonu te whatumanawa mōu e te rangatira. Kua tangi mai tō iwi o Te Whānau a Apanui me Ngāi Māori mā, anō hoki ko Aotearoa whānui tonu. Waihongia ō mahi whakahirahira me ō taonga tiketike hei hiki te wairua o te tini me te mano e whai ake nei. Moe marire mai e te tohunga.

A national museum, like Te Papa, is a rare and strange thing. It is not simply a big museum created by the state to give citizens a nice day out. Oh, to live in such a world! A national museum is actually a rather more serious proposition. It speaks of, and speaks to, the nation. It represents us and it serves us.

And overtly or implicitly it helps shape how we think about ourselves and who we aspire to be. It then tells this to the world. And it does all this using real objects. We are all used to museums, but when you think about it, they are pretty strange.

You might think that these days all of this can be squeezed into a mobile phone app, but it cannot. The museum is a special public space. It removes us from the everyday, from pressures of work, the city, the news and people trying to sell us things. Museum visiting is not simply about looking and reading, it is about having a space to think, socialise and negotiate. It puts us into contact with new ideas that are not part of our daily life or upbringing.

Now when you think about it, we have created quite a list of expectations of this public institution. We might find fun and pleasure in the national museum but as an institution it is very different from the theatre, cinema or video game. Indeed, no other visitor attraction or entertainment carries its level of responsibility and risk.

Looking at national museums around the world we can see how all this can lead to unfortunate results. In many countries, national museums are subject to direct political interference. In Britain and New Zealand, we expect our museums to have an ‘arm’s length’ distance from the partisan politics of

government and the vested interests of the commercial sector. By these means, and aided by professional staff who seek balance, objectivity and neutrality, national museums are often among our most trusted institutions. This status has, however, made them useful to unscrupulous governments as sites of political propaganda. This happened in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe before 1990, and can still be found in many parts of the world. Of course, the public is not stupid. Those living under Soviet influence soon learned to distrust the museum.

Elsewhere, national museums often display the evidence to support a national view of the history of a former conflict where the parties involved see things differently. Here you can find images and possessions of national martyrs. Other national museums have become home to political nationalism. They expect citizens to learn the defining symbols of the nation and to defend it against neighbours who are cast as threats to national security. These museums exist in very pleasant countries you might well visit.

Ever since Napoleon established the Louvre as a symbol of French greatness, national museums and galleries have been seen as essential institutions. They are among the first institutions a nation will build on achieving independence, regardless of its political persuasion or wealth. Fortunately, the vast majority of these museums are more likely to take inspiration from Te Papa and seek to realise a creative and autonomous population rather than disciples of narrow nationalism.

It is in this light that we should look at and reflect upon Te Papa. I cannot think of another national museum, built in the last forty years, that has been more globally influential in changing how these institutions represent the nation and, more generally, the indigenous peoples of the world. Indeed, it is hard to think of another national museum that has so fundamentally rewritten the ethics of being a museum. Te Papa is known and admired everywhere. It forced the big treasure houses of the northern hemisphere, like the British Museum in London and the Metropolitan Museum in New York, to think differently: to recognise their responsibilities and obligations. The product of a country of four million people, rather remotely placed on the globe, Te Papa is yet another example of New Zealand punching well above its weight!

In this book, New Zealand’s leading museologist, Conal McCarthy, takes us back to the moment when New Zealand’s biggest ever museum investment opened to the public 20 years ago. Fortunately for us, this is not simply a piece of historical research: Conal was there. Indeed, as I think about it now, Conal is as much a product of the revolution that affected the Museum of New Zealand as was Te Papa itself. His books Exhibiting Māori (Berg, 2007) and Museums and Māori (Left Coast Press, 2011) interrogate this revolution in museum practice, as well as its prehistory and its consequences.

The opening of Te Papa in 1998 was the culmination of a revolutionary journey that had begun in the early 1980s. That journey was not simply undertaken by the National Museum but by the nation at its heart as it redrew the Māori-Pākehā relationship, inventing a deep and sincere biculturalism that, as Conal explained in his earlier books, also possessed a helpful dose of local pragmatism. Even before the foundations of the new building had been laid, Te Papa was entering into debates in those parts of the world that have no indigenous minority as well as those that do. If, even now, Te Papa stands for a level of bicultural achievement rarely seen elsewhere, it is because the development of the museum and that of the country went hand in hand. Museums cannot bring about such changes on their own. They require government commitment. Nevertheless, the expertise and experience to be found in the museum and in its relationships are critical to the development of government policy.

Te Papa is very much what I would call a ‘contemporary museum’: it is focused on the needs of today and it does not shy away from the difficult issues. Indeed, it seems keen to face up to them. Without contaminating the beauty of the objects it displays, it nevertheless engages us with the lives of real people who speak directly to us from individual video displays. For me and many other visitors, this is a particularly effective form of interpretation, and it has been much copied.

Of course, no institution is perfect. As Conal explains, while visitor numbers were extraordinary and visitor feedback strong, the new displays were not without controversy. New museums are always of their time but the very best ones — like Te Papa — push the boundaries of what seems possible or desirable

The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (Te Papa) opened on 14 February 1998. The day was marked by food, music and celebration. Hay bales laid out on the forecourt of the museum lent the occasion a rural, and particularly Kiwi, flavour. New Zealand bands entertained the huge crowds. The sun shone, and the wind blew.

Just before midday, after a Māori ceremony, prayers, songs and speeches, Prime Minister Jenny Shipley said a few words:

As New Zealanders, we think of ourselves as young, as raw and fresh, but one day, in looking in the mirror, we find, to our surprise, we have grown up . . . This building behind us is such a mirror. It is a place where we can look at ourselves, at our past and at our present, at our natural heritage, at the unique mosaic of cultures that is New Zealand.1

At 12 o’clock, two children, a Pākehā girl and a Māori boy, holding hands with famous yachtsman Sir Peter Blake, declared the Museum of New Zealand open. For the public, this was the end of a long wait to see what was inside the new building on Wellington’s waterfront. For several years they had seen (and heard) the construction, and witnessed collections being shifted from the old National Museum in Buckle Street into their new home. From early in the morning the crowds lined up, and after the short opening ceremony they poured in. They kept coming, all that day up to midnight, and again the next day, and the next. The numbers were unprecedented.

For the staff, this was ‘day one’, the culmination of several years of hard work, dreaming, planning, developing and realising. There were feelings of exhaustion, relief, joy, and sadness for those who did not live to see the project completed. I was one of those staff, and I remember looking down from above as the crowd swept in the front door for the first time, to the sounds of Gareth Farr’s stirring music, specially commissioned for the occasion and performed by the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra. Then I ran up to level four to the Māori Discovery Centre Te Huka a Tai, which I had worked on, and was there when the first visitors came through the door, a local Māori family. ‘Kia ora,’ I said, ‘welcome to Te Papa!’

And the verdict? One of the performers, Don McGlashan, spoke to the audience at the end of his set with The Mutton Birds: ‘You have to go and look inside this place,’ he declared, pointing to the building behind him. ‘It is fantastic.’ The whole front page of the next day’s Dominion newspaper was emblazoned with the Te Papa brand, the now familiar stylised thumbprint, drawn on a cartoon hand raised in a thumbs-up sign of affirmation.

The public agreed, judging by the extraordinary response, which far exceeded the most optimistic visitor projections. The new museum attracted a large and genuinely diverse audience that included an unprecedented proportion of Māori visitors. Numbers averaged 2000 people on weekdays, rising to 6000 on weekends. Te Papa exceeded its annual target of 700,000 in three months. One million visitors came to the museum in five months and the first year, to February 1999, saw over two million.2 Over the next few years, as the figures mounted, Te Papa became the most visited museum in Australasia and the Pacific.3

Te Papa was not just a popular success. It certainly attracted people who did not usually attend museums or galleries, but it was equally recognised and lauded for innovative museological features that were at the forefront of international developments. Though New Zealand boasts many fine museums, Te Papa is the only one widely known outside the country. It is often cited in

1.

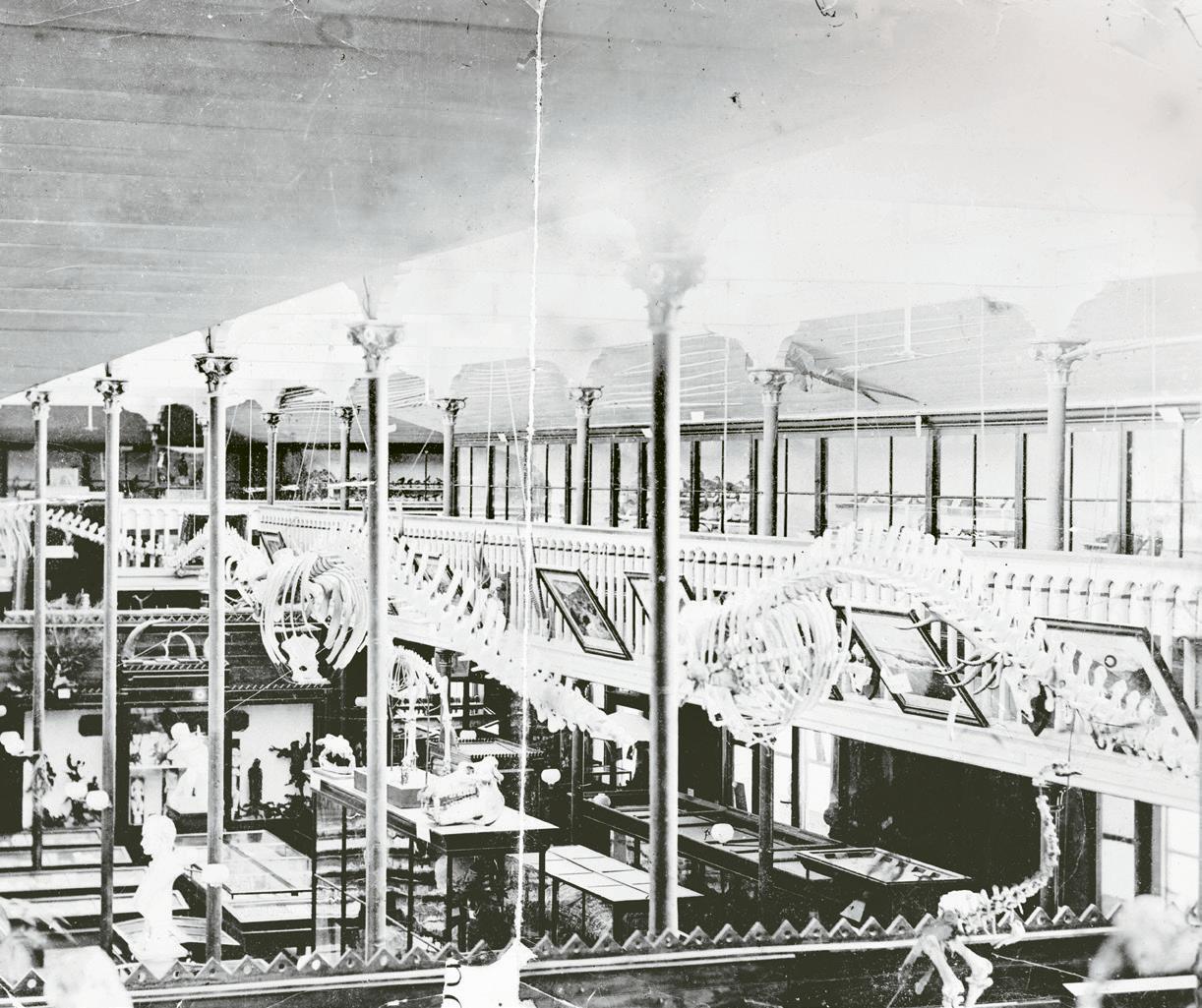

1. The interior of the Colonial Museum, Te Papa’s predecessor, on Museum Street, Wellington, photographed in the late nineteenth century.

2. The Dominion Museum, National Art Gallery and National War Memorial photographed not long after opening in Buckle Street, Wellington, in 1936.

art. It served its purpose well for a few years but, sequestered out of the city centre on a hilltop that was not connected to public transport, it quickly lost broad popular appeal and visitor numbers appear to have tailed off. There was a hiatus when the air force took over the building during World War II and it did not reopen until 1949. In the postwar decades other new attractions, such as television, competed for the attention of visitors in their leisure time.11

Turning inward from public and external demands, the institution focused on professional and scientific concerns: adding to its collections of fishes, plants, insects, birds and artefacts. Expeditions were mounted, new species were described, academic papers were written, and staff came and went.12 The postwar period saw growth in the number and variety of New Zealand museums: there were expansions in buildings and staff numbers, developments in professionalisation, improved display techniques, and growing awareness of education for schools (if not interpretation for the general public). Though they followed museological trends in Britain and, increasingly, Australia and the US, New Zealand museums began to look at the country’s own cultural heritage and national identity. In the 1960s and 1970s New Zealand history became a subject in schools and universities, and there was keen community interest in local museums, historic buildings and heritage sites.13

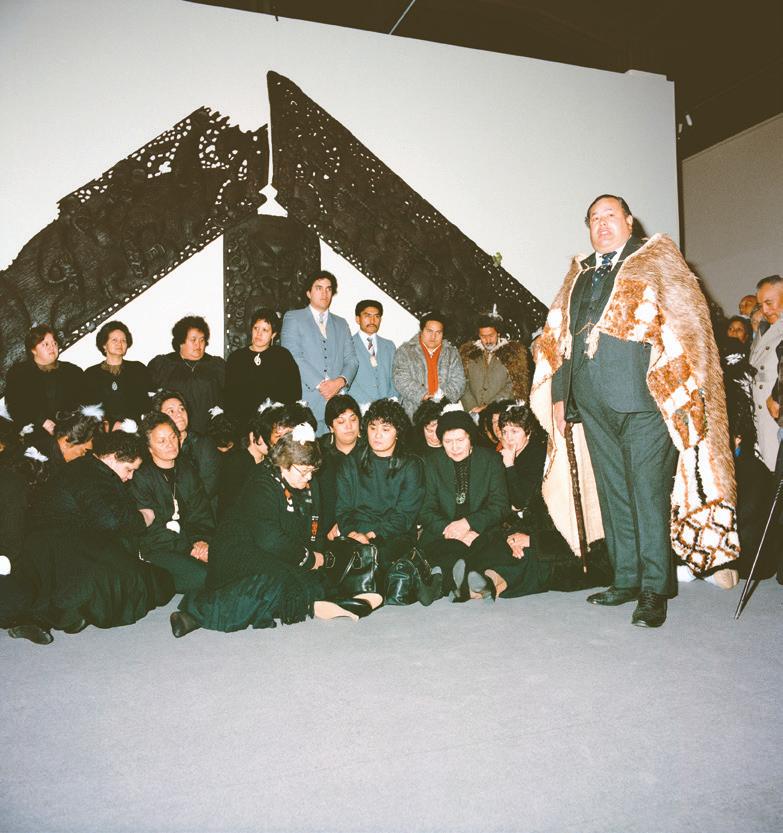

Then came a museological revolution. In the 1980s the famous Te Maori exhibition changed the direction of New Zealand museums and became a touchstone for the Māori Renaissance, a dramatic resurgence of Māori people, culture and identity that had been gathering pace for some time.14 Te Maori opened at the Metropolitan Museum in New York in 1984 and toured the US before returning to tour New Zealand in 1986–87, during which time it was seen by almost a million people. It was widely praised and emulated for the way it acknowledged Māori understandings of their carving as taonga, living ancestral treasures with a spiritual dimension, and also for the way it incorporated tikanga Māori (cultural practices) into opening and closing ceremonies. The exhibition has been credited with initiating sweeping changes in museums including an increase in Māori staff, the use of Māori language in labels, and stronger relationships with local iwi.15

When Te Maori: Te hokinga mai opened at the National Museum in 1986,

1. 2.

1. A scene at the opening ceremony for the exhibition Te Maori: Te hokinga mai at the National Museum, 1986.

2.

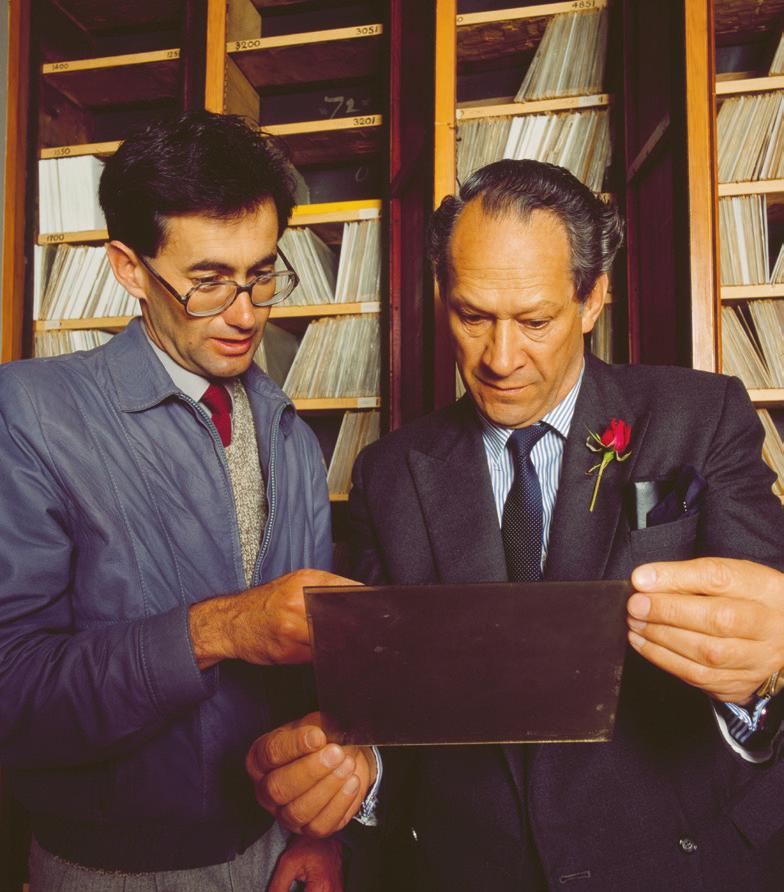

Dr (now Sir) Peter Tapsell, Minister of Arts, with history curator Michael Fitzgerald at the National Museum, Buckle Street, in the late 1980s.

3.

Iwi moving taonga to the new building on the waterfront, 22 March 1997.

there was widespread debate about the future role and mission of museums. Art critic Hamish Keith urged the museum sector to face the challenges posed by the exhibition. ‘None of these could be resisted,’ he said. ‘Te Maori had in any case made them inevitable.’16 By this time the National Museum had outgrown its building in Buckle Street, and its Māori, Pacific and history displays were showing signs of being out of step with a changing society. Plans for a new national museum overlapped with, and to some extent grew out of, the Te Maori exhibition. Certainly the museum came under pressure for change from Māori leaders in a period of intense debate about the contemporary relevance of the Treaty of Waitangi, New Zealand’s founding document.17

Historian James Belich has argued that this period of New Zealand history was marked by domestic ‘decolonisation’.18 Beginning in the 1960s and 1970s, when formal ties to Britain were loosened, externally New Zealand learned to make its own way in the world, while internally a sense of independent national identity sprang up. Confronted by Māori protest over land, language and political rights, Pākehā (European) New Zealanders were forced to reexamine their difficult relationship with their own colonial past. The stark reality of Māori impoverishment dispelled the old myth that God’s Own Country had ‘the best race relations in the world’. Simultaneously, cultural nationalism found expression through the visual arts, architecture, music and literature. Local debates were spurred on by international social movements: conservation of the natural environment, women’s liberation and the legalisation of homosexuality.19

Much of this political and cultural foment came together in the early and mid 1980s during the term of the Fourth Labour Government (1983–90), when Prime Minister David Lange oversaw a progressive social policy agenda that, ironically, was matched by neoliberal economic policy that resulted in restructuring, deregulation and unemployment. Some in the Museum of New Zealand project office thought that landmark cultural investments such as theirs got the go-ahead precisely because they represented an antidote to, perhaps even a distraction from, this gloomy backdrop.20 Meanwhile, the mood and tenor of government policy on Māori issues switched from paternalistic integration to a degree of self-determination. For example, the 1984 Hui

Moving on from the museum’s opening exhibitions in 1998 and its success with visitors, this chapter explores what was going on behind the scenes that led particularly to the successful public engagement with Māori audiences, usually underrepresented among museum visitors. Looking at the work of Māori staff in five different areas of the museum reveals where ‘bicultural’ museum practice was and is most active: policy, management, staff, collections and exhibitions. Throughout the text I draw on my own previous published work, primary and secondary sources including annual reports, policy statements, correspondence, documents and intranet resources, fleshed out by interviews and informal conversations with staff and my own first-hand observation while working at Te Papa from 1996 to 2000 and subsequent visits as a researcher.1

As noted in the Introduction, over the last thirty years the relationship between Māori and museums has been transformed: Māori have moved from being presented as colonised subjects whose captured material culture was displayed according to alien frameworks, to active audiences for exhibitions of their culture that incorporated their perspectives.

From outsiders to insiders, Māori are now working within museums as staff and board members, as well as being influential stakeholders and visitors. They have moved beyond models of consultation and collaboration to becoming