9 minute read

100 Years of Votes for Women

Q&A with Miranda Fraley, who curated 'Ratified! Tennessee Women and the Right to Vote

By Amanda Haggard

Ida B. Wells (1862-1931) began her lifelong crusade against discrimination and racially-motivated lynchings in Memphis during the 1880’s . She was instrumental in founding the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP); was a close associate of women’s suffrage leader Susan B. Anthony; founded the first suffrage organization among African-American women; was a leader in the NationalAssociation for Colored Women; and took part in the 1913 Chicago and Washington, D.C., suffragette marches. ALL IMAGES COURTESY OF THE TENNESSEE STATE MUSEUM.

By 1920, Franklin, Tenn.-born Maggie Sinclair Craig had served as a Red Cross nurse in WWI. She had also earned a special Red Cross certificate “in grateful recognition of the faithful and self-sacrificing service rendered during the Influenza Epidemic of 1918.” In 1920 she would see her work in the women’s suffrage movement end in the ratification of the 19th Amendment.

The federal government had passed the 19th Amendment the year before, but state legislatures were still embroiled in the attempt to ratify it — 35 states had approved the amendment and needed a 36th for it to pass. In mid-August of 1920, after much struggle, the final vote in favor of women’s suffrage came from Tennessee. Women like Craig may not be the first names people remember when they think of the ratification, but people like her all over the state fought for women to have power at the polls 100 years later, in Ratified! Tennessee Women and the Right to Vote, the Tennessee State museum will shine a spotlight on Tennessee’s role in the ratification of the 19th Amendment as well as showing how women all over the state fought for suffrage in the decades before. The 8,000-squarefoot exhibit includes artifacts, documents, large-scale graphics, videos and interactive elements — it includes items like Craig’s Red Cross uniform and her certificate for giving aid during the flu epidemic.

The exhibit was slated to open this spring, but it’s opening was stalled by the COVID-19 pandemic and will not open to the public until it is safe for people to gather in the museum.

While the museum isn’t sure when they’ll be able to open, on May 31, the museum will give a glimpse into the world of people fighting for suffrage with a special online offering called Ratified! Statewide!

“We’re still very much focused on our mission,” says Miranda Fraley, who curated Ratified! Tennessee Women and the Right to Vote. “We have been so grateful to be able to still do interesting work and provide services to the public even in this unusual time. … We’ve had some extra time to do extra research.”

Fraley, who has worked for the museum since 2004, talked to The Contributor about the history and context around the exhibit and what she learned in putting it together.

What do you think will surprise people about the exhibition? Are there people or stand out moments from places in Tennessee that we might not expect to see?

So the story of ratification in Tennessee has a certain level of being famous. But I took the work really as looking at women through this state who got to that point. And one thing that we’ve really tried to do and this exhibit and this big, our mission, I think this statement is we really tried to book for this story from all the different parts of the state, right? What was going on? What debates are people having? Because of the ratification battle, there were over 70 [suffrage groups] separately all throughout the state. So it’s, it’s like a lot of times the really well known leaders people have heard of like Anne Dallas Dudley —and their stories are certainly addressed as well — but we’re also looking at, you know, what were women in Pulaski doing? And what were women in Union City doing. And we really hope that visitors are going to enjoy that.

This seems like such a huge undertaking.

Yes. One of the things we’re really trying to do is put these things in historical context to what came before and what came after. Even really early in Tennessee history, we see how women were acting politically long before they had the vote long before the suffrage movement really started. It’s a trend in political history to define political history both sort of broadly and to book at the more traditional things like voting too. So we’ve really tried to provide a fuller context. These exhibits are always very much team projects, right? They involve pretty much everyone in the museum, which is a great thing.

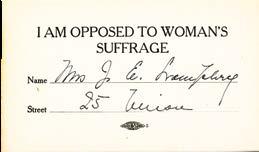

I’m curious about how you depict the opposition to suffrage in the exhibition.

Sure. Yeah. It’s a really critical part of this story … there was deeply entrenched opposition and it didn’t go away. Even after ratification, there were indignation meetings throughout the state. People were angry that that amendment had been ratified and that suffragists continued on in politics. They encountered a lot of backlash from people who still really didn’t accept women voting. In my research I found an editorial in a paper with a woman writing after receiving the right to vote, asking why women are being told that basically they’re doing something wrong if they go and vote. We had this right now, but it was still very much contested.

So in Tennessee, it gets a little complicated and we address this in the exhibit — that women in Tennessee gain presidential and municipal suffrage in 1919, but they don’t get the full voting rights until the 19th Amendment is ratified. And some scholars have done really great research on women’s voting patterns: Some of the newer scholarship especially has looked at women in Southern states because what happens is in 1919 and 1920 in Tennessee women can vote without paying the poll tax. But in 1922, the poll tax was imposed on women and that had a big impact. And you start seeing things like Sue Shelton White who was a leader form Hendersonville, basically saying that if women have to pay a poll tax that in most times the husband still had control of the purse and therefore control over her vote.

Of course, there were a lot of barriers experienced by African American women, both within the suffrage movement and in other attempts to disenfranchise African Americans. But some [of the tax records] show women paying their own and it was really exciting to see, especially those records documenting African American women paying those poll taxes that were designed to exclude them. It’s really exciting to get down to that level of research where you learn things about the actual individual and the story.

During the fight for women’s suffrage, white women weren’t exactly helpful to a lot of black women. Do you have anything in the exhibition that speaks to that part of the history?

That’s a very important part of its story, the suffrage movement. And this does examine that scene. We look at relationships between white suffragists and African American women — many African American women were involved in organizational work during this time period. Even when they were excluded from Stouffer’s organization, many African American women chose to work for suffrage, both for themselves and in the fight against the disenfranchisement and the issues that had been put in place to keep African American men from voting.

Tell me more about Ratified! Statewide! Was this a pivot because of the pandemic, or was this component always going to be part of it?

Joe Pagetta, Director of Communications at the Tennessee State Museum: Miranda had done this extraordinary research scholarship on the surface. She went throughout the state to find narratives from every county in the state and initially it was going to be like a newspaper take away in the gallery. It’s still going to be when we’re able to open, but the idea was to tell the story of the whole state as it relates to suffrage. We had planned this online the whole time, but this sort of moved the online part to a priority and a way to tell the story.

Do you have a favorite piece in the exhibition?

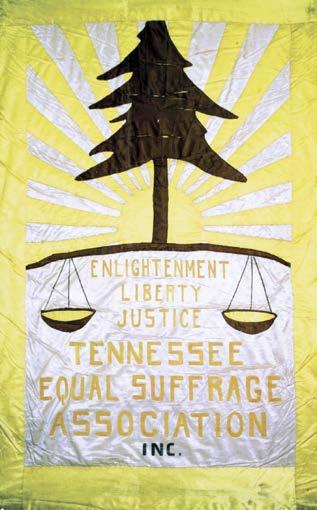

It would probably be the banners that were used by Tennessee suffragists — two of them are going to be an exhibit. One of them is on display in our long term exhibit and the banners are great. The one I’m thinking of particularly, there was for a statewide separate organization and it features an evergreen tree. It’s yellow and it has a big tree on it — these great images we found from rallies and it looks like these are the same ones or the same style. We were really excited about that, to kind of hopefully see it or a similar one in action. But the thing is, I think they’re so great because they were actually used by this effort and they were really important to them. When I was researching stories of suffragists throughout the state, there was a group that entered a decorated car and basically a local town parade and they won first prize and then used the prize money to pay their dues to the state to be able to vote. So they were really important to this effort and a symbol of the movement and they’re beautiful objects.

Fear of COVID not accepted as reason for mail votes

Tennessee Secretary of State Tre Hargett says eligible Tennesseans can request a mailin ballot for the Aug. 6 elections.

But officials have also said that fear of getting the coronavirus won’t be accepted as a reason to mail in a ballot.

“In consultation with the Attorney General’s office the fear of getting ill does not fall under the definition of ill,” Coordinator of Elections Mark Goins said in a statement to the Associated Press.

Eligible voters must meet certain criteria such as being 60-years-old or older. A list of reasons from the Secretary of State:

• The voter will be outside the county where they vote during the early voting period and all day on Election Day.

• The voter or the voter’s spouse is enrolled as a full-time student in an accredited college or university outside the county of registration

• The voter will be unable to vote in person due to service as a juror.

• The voter is hospitalized, ill or physically disabled and because of such condition, cannot vote in person.

• The voter is a caretaker of a person who is hospitalized, ill or disabled

• The voter will be working as a poll official.

• The voter is a member of the military and out of the county where they vote.