“…the great state University of Wisconsin should ever encourage that continual and fearless sifting and winnowing by which alone the truth can be found.”

University of Wisconsin-Madison

Since 1892 dailycardinal.com

Fall Action Project 2022

PHOTOS BY DICK SATRAM, DRAKE WHITE-BERGEY, GAVIN ESCOTT, KORGER AND MARK KAUZLARICH

GRAPHICS BY DRAKE WHITE-BERGEY, MADISON SHERMAN AND ZOE BENDOFF

“…the great state University of Wisconsin should ever encourage that continual and fearless sifting and winnowing by which alone the truth can be found.”

University of Wisconsin-Madison

Since 1892 dailycardinal.com

Fall Action Project 2022

PHOTOS BY DICK SATRAM, DRAKE WHITE-BERGEY, GAVIN ESCOTT, KORGER AND MARK KAUZLARICH

GRAPHICS BY DRAKE WHITE-BERGEY, MADISON SHERMAN AND ZOE BENDOFF

Down the drain: Money Wisconsinmisses by

By Zoe Kukla STAFF WRITER

By Zoe Kukla STAFF WRITER

In early November, Dane County residents voted in favor of mari juana legalization in a non-binding referendum — for the third time in eight years.

Dane County residents aren’t alone. A Marquette Law School poll from October found 64% of Wisconsinites support legalization, continuing a six-year streak of broad support for marijuana legalization in Wisconsin.

Yet, marijuana remains crimi nalized in Wisconsin with no clear plan for legalization. Not only are Wisconsinites missing out on the marijuana market, but Wisconsin’s economy lacks the benefits of an increasingly profitable industry, according to Democratic Gov. Tony Evers’ o ce.

Evers has called for support of marijuana legalization and pro-med ical legislation. His o ce estimates cannabis sales would generate $165

“Legalizing and taxing marijua na in Wisconsin — just like we do already with alcohol — ensures a controlled market and safe product are available for both recreational and medicinal users and can open the door for countless opportunities for us to reinvest in our communities and create a more equitable state,” Evers said.

Evers’ plan would require cooper ation from Wisconsin Republicans, who control the Legislature. However, Republican support for legal marijuana is sparse.

Assembly Speaker Robin Vos (R-Rochester) told the Associated Press he supports medical marijuana legalization in 2019 but that the pro cess is ”going to take a while.”

Vos has supported a limited legal ization of medical marijuana avail able only in non-smokable forms for chronic medical conditions since then but continues to oppose legal izing recreational marijuana.

Senate Majority Leader Devin LeMahieu has said he doesn’t back legalization without FDA approval.

“If the federal government delists it and it goes through FDA testing, then it should be treated like any other drug,” LeMahieu said at a WisPolitics cheon in April 2021. “If there’s advantages to it, if it helps out people, I have no problem with it as long as a doctor’s prescribing it.”

“I think that discussion needs to be done at the federal level and not have some rogue state doing it without actual science behind it,” he added.

The costs of prohibition

With marijuana illegal in Wisconsin, state residents satisfy their cannabis fix across state lines.

cannabis caged

The drug is popular among young people nationwide despite still being criminalized. More than four in 10 young adults ages 19 to 30 used marijuana during the past 12 months, according to a 2021 study from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

That means neighboring states like Michigan, which legalized rec reational marijuana use in 2019, are raking in the green from sales tax revenues.

Last year alone, Michigan recorded $1.3 billion in marijua na sales for recreational use and over $480 million for medical, according to Michigan’s Cannabis Regulatory Agency.

Those sales generated more than $111 million in marijuana sales tax revenues during the 2021 fiscal year, according to the Michigan Treasury Department. Approximately $42 million of that money was redistribut ed to municipal govern ments in March 2022.

Some of that tax revenue comes from Wisconsinites who travel across state lines, including University of WisconsinMadison students. A Milwaukee Journal Sentinel article even described a Michigan dispen sary parking lot filled with cars bear ing Wisconsin license plates.

“It’s honestly very beneficial since I can get medical marijuana,” said a UW student who wished to remain anonymous. “It’s better for me and plus, it’s way more e cient and safer instead of getting it o the street.”

Evers lamented about missed tax revenue from cannabis sales going to neighboring states in a Twitter video last year, where he recalled a conver

sation with Illinois Gov. J. B. Pritzker. “We talk about this often because he’s really glad that we have not legal ized marijuana because the taxes that are made in Illinois from legal sales of marijuana helps them out a hell of a lot,” Evers said.

Wisconsin would not only ben efit from the tax revenue on mari juana, but if decriminalization laws are implemented, the state could save money on yearly arrests.

Marijuana possession arrests accounted for 57% of all Wisconsin drug arrests in 2018, according to the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). Arrest rates are disproportionately high for Black residents, who are 4.2 times more likely than white residents to be arrested for marijuana possession in Wisconsin.

The ACLU also estimated Wisconsin taxpayers could save approximately $3.5 million if mari juana possession arrests were cut in half in a 2012 report. That number rises to nearly $4.5 million when adjusted for inflation using the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ inflation calculator.

The ACLU’s estimate does not include the costs of jailing the arrest ed or court costs for prosecuting and incarcerating arrests that lead to a jail or prison sentence.

As governor, Evers granted 603 pardons to people convicted of can nabis possession. But the Democratic governor told UW-Madison students in September that he was “really tired” of prohibition.

“We have to make sure that the use of marijuana is not something that gets you into the criminal jus tice system,” Evers said. ”We need to legalize it.”

Dane County works to reduce drug harm

By Jasper Bernstein and Reuben Berkowitz STAFF WRITERS

Faced with a growing drug cri sis, Dane County Public Health leaders are taking steps to ensure the safety of the community in respect to drug usage.

“We are in the midst of a drug overdose crisis,” Public Health Madison and Dane County, the local health department, said. “Since 2000, Dane County has seen a 139% increase in the number of people who died of a drug overdose.”

In Dane County, 365 people died because of drug overdoses from 2018 to 2020 — the largest cause of deaths being fentanyl. The substance was detected in 75% of deaths from drug overdoses in a report from the Dane County Medical Examiner.

There continues to be an increase year by year of overdose deaths in Dane County — 4.2 times the rate of motor vehicle deaths. According to the report, opioids are the main cause of this continuous increase, and synthetic opioids like fentanyl are mostly at fault.

Amid this crisis, Public Health Dane County and Madison began the Dane County Overdose Fatality Review. The review, among other steps, seeks to address the drug epidemic through increased access

and education to naloxone (a life saving anti-opioid overdose medi cation) and supplies like fentanyl test strips, overdose spike alerts and the support of mental health and substance abuse rehabilitation.

“[Public Health Madison works] to reduce harms to people who use drugs and aims to treat them with dignity and respect,” said Julia Olsen, Public Health Supervisor for Madison and Dane County. “[The program o ers] a non-judgmental space to access safer use supplies and have con versations about their needs.”

Olsen also explained how the criminal justice system has his torically had a “war on drugs” approach, where the emphasis has been on arresting drug users rather than rehabilitation.

“Speaking on a general level, drug policy in the United States treats the chronic disease of addiction by criminalization,” said Olsen. “There is more work we can do to help law enforcement and other systems adopt harm reduction approaches.”

Wisconsin’s Good Samaritan Statute does not provide any pro tection to individuals after an over dose and very limited protection for those who call for help, per the Madison and Dane County Drug Overdose Annual Report.

“People surviving an over dose are often arrested on a drug charge and taken directly to jail from the hospital,” the report said. “Making people criminals because they suffer from addic tion is expensive, ruins lives, and can make access to treatment and recovery more difficult.”

Olsen emphasized how the overdose fatality review aims to achieve this anti-criminalization — through exclusive programs with law enforcement.

“[The program] collaborates with law enforcement on ways to keep our community safe,” Olsen explained. “Some exam ples include the Madison Area Recovery Initiative (MARI) and the Pathways to Recovery pro gram. These programs help divert people from the criminal justice systems to treatment, recovery, and peer [support].”

Faced with long standing sys temic bias, communities of color have experienced issues with unequal access to resources to fight drug usage.

“From 2018-2020, the drug overdose death rate among Black people was more than 3 times the rate among white people,” Public Health Madison and Dane County said in the report.

As shown in the Dane County

Overdose Fatality Review, Black people have experienced steep increases in drug overdose rates in the past decade — the overdose rate for the Black population in Dane County from 2018 to 2020 was 71.2 per 100,000 people as compared to 21.7 per 100,000 over the same period for white people and 10.4 for the Hispanic/Latino population.

“[Dane County Public Health recommends examining] quanti tative and qualitative data beyond deaths to better characterize the experience of Black people with substance use disorder in Dane County, including the social, cul tural, and illicit drug market factors that are driving the rapid increase in drug overdose death in this pop ulation,” the report stated.

The review is working to elimi nate racial disparities in overdose deaths with the African American Opioid Coalition, along with e orts to promote health equity in over dose prevention and response.

“It is our responsibility as Public Health to call attention to these inequities, advocate for, and help implement change to reduce inequities,” Olsen said about the initiative. “Part of our job is also to help systems understand alterna tive evidence-based harm reduction practices exist and help implement them locally.”

2 Thursday, November 10, 2022 dailycardinal.com news

keeping

608-262-8000 or send an email to edit@dailycardinal.com. For the record An independent student newspaper, serving the University of Wisconsin-Madison community since 1892 Volume 132, Issue 13 2142 Vilas Communication Hall 821 University Avenue Madison, Wis., 53706-1497 (608) 262-8000 News and Editorial edit@dailycardinal.com News Team News Manager Hope Karnopp Campus Editor Alison Stecker College Editor Anthony Trombi City Editor Charlie Hildebrand State Editor Tyler Katzenberger Associate News Editor Ellie Bourdo Features Editor Annabella Rosciglione Opinion Editors Priyanka Vasavan • Ethan Wollins Arts Editors Jeffrey Brown • Hannah Ritvo Sports Editors Donnie Slusher • Cole Wozniak The Beet Editor Mackenzie Moore Photo Editor Drake White-Bergey Graphics Editors Jennifer Schaller • Madi Sherman Science Editor Julia Wiessing Life & Style Editor Sophie Walk Copy Chiefs Kodie Engst • Ella Gorodetzky Copy Editor Julia Chumlea Social Media Manager Clare McManamon Business and Advertising business@dailycardinal.com Business Manager Asher Anderson • Brandon Sanger Advertising Managers Noal Basil • Sydney Hawk Marketing Director Mason Waas run by its staff members and elected editors. It subscription sales. The Daily Cardinal is published weekdays and distributed at the University of Wisconsincirculation of 10,000. printer. The Daily Cardinal is printed on recy cled paper. The Cardinal is a member of the Newspaper Association. of the Cardinal and may not be reproduced without written permission of the editor in chief. Complaints: News and editorial complaints should be presented to the editor in chief. cessed and must include contact information. No anonymous letters will be printed. All letters to the editor will be printed at the discretion of The Daily Cardinal. Letters may be sent to opinion@ dailycardinal.com. Media Corporation Editorial Board Em-J Krigsman • Anupras Mohapatra • Jessica Sonkin • Priyanka Vasavan • Sophia Vento • Ethan Wollins

Baumann • Ishita Chakraborty • Don Miner • Nancy Sandy • Phil Hands • Josh Klemons • Barbara Arnold • Jennifer Sereno

Sophia Vento Managing Editor Jessica Sonkin

Board of Directors

Editor-in-Chief

ZOE BENDOFF/THE DAILY CARDINAL

UW-Madison students find community in collegiate addiction recovery program

Is it decriminalized? Clearing up the confusion about marijuana policy in Madison

By Sarah Eichstadt STAFF WRITER

Over 14,000 people are arrested for marijuana possession every year in Wisconsin, according to 2019 data from the Milwaukee County District Attorney’s o ce.

Dane County historically has lower marijuana conviction rates, convicting people about seven times less than the average Wisconsin county. Madison has moved towards decriminalization.

Marijuana violations in Madison may have di erent consequences on versus o campus at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. In most cases, simple possession of marijuana will have no or minimal consequences, unless accompanied by other o enses. However, selling marijuana can have more serious consequences.

Here’s a look at the state, city and university policies that guide marijuana enforcement and norms in Madison.

gun and a significant amount of cash, and they have a scale and several bags of marijuana broken out into sellable amounts’ — that is indicative of intent to deliver,” Lisko said. “That would be something that would result in a state criminal charge. The easiest way for people to avoid that is to not be involved with the sale of marijuana or to abide by possessing less than 28 grams of marijuana at any time.”

UW-Madison

The University of WisconsinMadison Police Department (UWPD) has its own policies and is not bound by city ordinances. UWPD follows the UW Administrative Code and state statutes.

Marijuana incidents that UWPD encounters range from non-criminal citations — essentially a ticket — to felony o enses for dealing.

By Madeleine Afonso STAFF WRITER

University of Wisconsin-Madison students are surrounded by a preva lent party culture on campus that con sists of going out on the weekends, tailgating on game days and hitting the bars — which oftentimes involves drinking. For a certain group of stu dents, this aspect of campus culture is avoided for that reason.

Students in active recovery from substance abuse and addiction can turn to Badger Recovery, a program that holds peer-to-peer weekly meet ings to aid those on their recovery journey or looking to start.

“Everyone’s on their own path of recovery,” said Jenny Damask, who helped found the program in September 2020.

Damask, who is the assistant direc tor for high-risk drinking prevention at University Health Services, said the program was initially launched in an all-virtual format but now holds inperson meetings with a virtual option. Attendees can be connected with coaching and resources on recovery and find community among others in similar positions as themselves.

According to Damask, the meet ings do not subscribe to typical recov ery-type meetings like Alcoholics Anonymous, which are geared toward adults and community members. Instead, Badger Recovery is centered on students’ experiences.

“We really just want to be this welcoming place where people in recovery can thrive,” she told The Daily Cardinal. “And talk about con cerns or struggles or triumphs that they’re experiencing.”

Peer-to-peer support and con nection at meetings are facilitated by Badger Recovery student assistants, who plan bonding events that aim to generate friendships outside of time in discussion, Damask said.

Henry Hank, a 26-year-old Badger Recovery student assistant in recov ery, said he finds it easy to steer clear of the party culture on campus because he came to the university with over two years of sobriety.

“Part of me still feels like there is the [fear of missing out], and I wish I could still be a part of the culture

of, you know, living on campus and connecting with people in that way,” Hank said. “But I know from past experiences how shallow all that is.”

Hank said he stayed at outpa tient centers and attended 12-step recovery meetings while he fought substance abuse for hard drugs over several years after graduating high school.

“I usually try to stay away from bringing that up in the meetings because I’m not trying to scare away anybody,” he said. “A lot of people are there for like nicotine, and we’re not trying to make them feel less then. But I mean, that’s just the reality of my story.”

Discussion about experiences and feelings in recovery meetings can feel uncomfortable and abnormal, but it gives students an opportunity to get advice, vent and cultivate a sense of fellowship, especially for most who have not participated in a recovery meeting before, Hank explained.

“We’re getting vulnerable and talking about things we’re struggling with,” he said. “That’s not normal, I know how it’s not normal.”

Recently, students and student assistants have been following meet ings with dinners on State Street together, which Hank said will help the group feel like a community that’s more than just seeing each other twice a week for an hour.

“It’s just something good to do,” he said. “And at a minimum, it’s like one hour or one night that you’re not going to go out and drink.”

Badger Recovery received anony mous participant statements from a survey they sent out once, and many noted how the program has provided a campus community that feels like home, where members can open up, be vulnerable and share struggles that some don’t get a chance to in typical social situations.

“I feel more included at UW-Madison. I feel I have a safe place to talk about my feelings and issues. I enjoy helping and supporting others,” one Badger Recovery member said.

According to Damask, that’s what peer-to-peer recovery is all about — finding community and finding who your people are. She said oftentimes,

members will find community no mat ter what because there are similarminded people coming in to talk about similar things.

“When we’re bringing together people in recovery, there’s going to be people you’re naturally gravitating towards,” Damask said.

“It’s made me feel less alone, and I’ve been given a lot of valuable feedback and suggestions from my peers that have improved my mental and physical well-being,” another member added.

Damask and Hank both pointed out the lack of sober dormitories, rooms or centers on campus and how that’s something they hope for in the future. They said other colleges simi lar to UW-Madison have well-estab lished collegiate recovery programs already with sober living spaces.

“I mean of all campuses, [UW-Madison] is one that could use it, honestly,” Hank said.

They also hope to expand their services with more targeted outreach, in particular potential identity groups for women or LGBTQ+ communities, and groups for graduate students, Damask said.

Hank said he would like to see more people at meetings and increase awareness of the program, but it’s di cult because, unlike most other student organizations, not everyone can participate.

“For a lot of college kids, [they’re] really early on to figuring out, or are not even aware, that they’re overdo ing something,” he said. “I think a big way to [expand] is to get more aware ness around the program. I think a lot of students don’t even know that it’s o ered.”

“If we can help people maintain recovery and goals around well being and wellness, we can give [students] years of their life back,” Damask added.

Students looking to learn more about the collegiate recovery pro cess at UW-Madison can read more on the UHS website or email a sta member at recovery@uhs.wisc.edu. Badger Recovery meetings are held every Tuesday and Thursday in person at College Library or online via Zoom.

The City of Madison Hunter Lisko, the public informa tion o cer for the Madison Police Department, said enforcement of marijuana-related incidents is “cir cumstance dependent.” Madison is often said to have decriminalized marijuana, but Lisko says this isn’t the best terminology.

“The word decriminalized I think can be misleading,” Lisko said. “While it might not be legal, we’re not neces sarily interfering or taking enforce ment action if it’s just marijuana pos session — if there’s not another coin ciding thing that we’re looking into.”

Possession of marijuana is still illegal in Madison. However, the Dane County District Attorney’s Office won’t prosecute an adult for simple possession of fewer than 28 grams unless it violates certain circumstances.

The City of Madison Police Department Standard Operating Procedure prohibits possessing mar ijuana within 20 feet of a school, on a school bus, in an operating vehicle or on “property open to the public” without permission.

Lisko said most marijuana-related incidents resulting in enforcement actions are combined with other crimes. Behavior that impacts public safety or creates significant distur bance is more likely to be addressed.

“Then it becomes disorderly con duct or trespassing to a business,” Lisko said.

The consequences for dealing marijuana in Madison are di erent from personal use. If an o cer finds evidence of “intent to deliver,” enforce ment can be expected.

“If I think, ‘Okay, this person has a lot of marijuana and they have a

Assistant Chief Brent Plisch of UWPD said most on-campus mari juana interventions involve other violations such as alcohol, theft or vandalism. O cers tend to be more likely to take action on these addi tional factors rather than issuing a ticket for marijuana.

On top of a police penalty, stu dents may face additional conse quences from the university. The UW Administrative Code states that mari juana is handled in the same way as alcohol violations. First-time o end ers receive a warning and online can nabis education. A second o ense results in a short probation period and referral to Cannabis Screening and Intervention for College Students (CASICS), which involves personal assessments and one-on-one sessions with an abuse counselor.

“In the sessions, students will have a structured opportunity in a non-judgmental setting to assess their individual risk and identify potential changes for the future,” the adminis trative code says.

Suspension is a risk if a student is dealing marijuana.

Plisch said when o cers respond to a marijuana-related incident, a lot of times it is because of a complaint from the community.

“Let’s say in a residence hall some body may call in because they have asthma or they’re allergic to smoke and their neighbors are constantly smoking,” Plisch said.

Plisch said o cers have a lot of flexibility in how they handle mari juana incidents, but they are trained to take “behavior-based” actions.

“We take action based on behaviors and things that are hurtful to other people in the community,” Plisch said.

There have been 32 marijuanarelated cases this year, according to Plisch. Two of the cases resulted in criminal charges, both because of the involvement of harder drugs.

Legal consequences in Wisconsin

Jail time is a possibility for mari juana crimes, even for simple posses sion, Teuta Jonuzi, a defense attorney at Tracey Wood & Associates, said.

Both possession and dealing of marijuana can result in fines of up to $1,000 and six months of jail time for the first o ense. The second o ense can result in up to $10,000 in fines and three and a half years of jail time, according to Jonuzi.

news

dailycardinal.com Thursday, November 10, 2022 3

Readmore@dailycardinal.com

MADI SHERMAN/THE DAILY CARDINAL

OF FLICKR USER ELSA OLOFSSON VIA CREATIVE COMMONS

COURTESY

UW-Madison implements Nalox-ZONE boxes in residence, dining halls

are two doses of a nasal spray Naloxone, also known as Narcan, and a CPR face mask.

Damask wants people to understand that fentanyl lacing is occurring in Dane County and surrounding areas. Discussing the problem and normalizing solutions in university buildings is one of the first steps of destigmatizing the topic, she said.

“It’s not like this far o thing, it’s in our community,” Damask said. “I would hope more people will see the boxes as a thing that we have, where there’s no stigma. It’s just we have it and it could save a life.”

information boards.

Both residents agreed they had no concrete idea as to where the boxes were located in dorms and which dorms housed them.

“If I were in a situation where I had to locate it, the first place I would have looked would be near the AED because that’s where emergency items would be, but I’ve never actually seen it,” Shields said.

Damask and Kopp said the boxes should be used if you ever suspect an overdose. Using the narcan will not harm the individual, even if they are not overdosing.

“We’re almost prescribing Naloxone campus wide and making it free, which is lifting a huge, huge barrier from act to access,” Damask said. “This is just a way to make it more available and free.

“If you need it, you should take it,” Damask added.

Goodman and Shields agree there is a sense of comfort that comes with knowing the NaloxZONE boxes are in place. However, the next step is to educate and further inform the resi dents, they said.

By Beth Shoop STAFF WRITER

Several University of Wisconsin-Madison residence and dining halls now house NaloxZONE boxes, containing the medicine Naloxone, to prevent possible drug overdoses. The boxes are placed among other emergency tools such as AEDs and fire extinguishers as a way of mak ing them easy to find and as common as other safety tools.

The purpose behind the boxes is to help reduce the possibility of drug overdoses on cam pus, especially with the rise in fentanyl-laced drugs. University Health Services Assistant Director of High-Risk Drinking Jenny Damask said cheap, potent fentanyl is being added to drugs and distributed, leaving many at risk.

“People are dying from drugs laced with fentanyl,” Damask said. “We had an incident pretty close to home where a student in a resi dence hall at UW-Milwaukee passed away from a fentanyl overdose.”

Fentanyl overdoses became the leading cause of death in people ages 18 to 45 in 2021. In Wisconsin, the number of fentanyl related deaths grew 97% from 2019 to 2021.

Other University of Wisconsin System schools have implemented these safety boxes in common areas. UW-Madison used the University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh as the blue print for the Nalox-ZONE box installation, Damask explained. The contents in the box

Along with reducing stigma, raising awareness for young adults about the NaloxZONE boxes will help them feel more com fortable using the drug if necessary in an emergency. Chadbourne Residential College House Fellow Kaldan Kopp made his resi dents aware of the boxes along with their purpose and how to access the simple instruc tions on the nasal spray.

“I texted the GroupMe about the boxes,” Kopp said. “I just told my residents it’s down stairs, and I also mentioned it in one of my floor meetings.”

Along with informing his floor of the loca tion of the box, Kopp also explained the simple steps that can be followed along with using the box’s contents. He said residents should use the narcan, call 911 and then call the House Fellow on duty.

While Kopp mentioned the Nalox-ZONE boxes to his residents, Kronshage Residence Hall resident and first-year student Callie Goodman was only notified of the boxes through a screen in Four Lakes Market, the dining hall housed in Dejope Residence Hall.

“The only reason I knew about the boxes was because they had an ad for them in the din ing hall. I stopped and looked at it and saw that they had di erent locations around campus, but no one’s ever talked about it,” Goodman said.

Barnard Residence Hall resident and sophomore G.M. Shields had a similar expe rience, and only became aware of the box installation through emails and residence hall

“If you suspect someone took something and they’re having an overdose, there’s no great harm to being wrong and using it,” Kopp said. “It’s better to be safe than sorry.”

All House Fellows went through an hourlong training session to understand how to use the Naloxone and where it would be located. The group was trained by health department professionals who assisted in the installation process, Kopp explained.

UW-Madison worked with the Wisconsin Voices for Recovery movement to install the boxes around campus. The movement team worked with residence halls to place the boxes and monitor the contents inside, according to Damask.

The Nalox-Zone boxes have a WiFi con nection that emails residence life coordinators when the box is opened. Signals are sent to the individuals monitoring the box to check and see if it needs to be refilled. Wisconsin Voices for Recovery then comes to replenish the boxes.

While the Narcan doses can be used in an emergency, Damask and Kopp agreed some people feel safer having it in their possession, such as in their backpack or dorm room, as a safety precaution.

“I know some people ordered it themselves because you can get certified, order it, and keep it, so I’m considering doing that as well,” Kopp said.

Damask believes having a free safety mea sure open to all UW-Madison students is going to be beneficial for everyone on campus.

“It’s nice and comforting to know that if someone needed it, they could get help for us, especially from another student,” Goodman said. “I think the university should do one of those information modules that you have to do for sexual assault and alcohol for these boxes. Students have to know where they are and how to use them because you don’t have much time when an emergency happens.”

Shields agreed with the idea of creating new information modules on the Naloxone doses and added that sending emails is not enough to truly inform students.

“I would bet that most people don’t read those emails. I would be willing to bet the majority of students do not know the boxes were installed,” Shields said. “Out of the whole student body, definitely a minority of people know, but even of the people who do live in UW Housing, I definitely think it’s a minority. It should have been more than email because not everyone reads emails.”

Damask and Kopp want students on campus to understand there is no harm in trying to help others. The Nalox-ZONE boxes are in place as a safety measure that should be used without stigmatization in an emergency situation, just as any other tool would be, they explained.

“I hope we never need it, but if we do, it’s there. That’s the same way I feel about an AED and a fire extinguisher. That’s the kind of thing I want to normalize,” Damask said. “We have a lot of work to do to still educate our students on what Naloxone is, how to use it, and what fentanyl lacing is, but this is a start.”

A historical look into medical, recreational cannabis use

By Allie Waino STAFF WRITER

At the University of WisconsinMadison, the School of Pharmacy decided that informing students on the history of marijuana, a drug that is currently illegal in the state of Wisconsin, is valuable knowledge to educate students on before they enter the workforce.

Lucas Richert, an associate pro fessor at UW-Madison, as well as a historian of medicine and pharmacy, focuses on both legal and illegal drugs, and has been a proponent of educating UW Pharmacy students, specifically on the history of marijuana.

Although educating future phar macists and medical professionals on cannabis may be new to the Division of Pharmacy Professional Development (DPPD), according to Richert the study of cannabis for medicinal pur poses is not.

“It’s important to remember that cannabis has been used within medi cal circles for centuries, to varying degrees of course,” Richert said. “Scholars in the School of Pharmacy and in the U.S. pharmaceutical indus try, for example, studied cannabis over a hundred years ago — just as they are now.”

Similarly, the debates around medical cannabis are long standing, according to Richert.

“The debates we are having about medical cannabis now aren’t new,” Richert said in a DPPD article. “These debates have been waged all over the world, and some of the dif ferent therapeutic modalities we have now, and generally, the way cannabis is being used today, also has echoes in the past.”

To have a nuanced understanding of the history of cannabis, knowledge on the drug needs to extend past its medical uses, Richert explained.

“[It is important to remember] you can’t think critically about pharmacy and drugs, including cannabis, with out thinking about race and class and gender, as well as politics,” Richert said. “The proper or poor ‘Scheduling’ of a substance (and its acceptance as a medicine or not) impacts law enforce ment and race in society. It impacts social justice and equity. And it impacts the economy, sometimes for the worse.”

The term “Scheduling” refers to the categorization of a drug into one of five di erent categories. The categories are distinguished by a drug’s acceptable medical use, and abuse or dependence

potential. They are “Scheduled” by the United States Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA).

Cannabis is currently recreation ally legal in Wisconsin’s neighboring states of Michigan and Illinois. In Minnesota, it is medically legal, and in Wisconsin low THC doses are legal for medical use.

However, the bill LRB-4361 has been put forward by Wisconsin Democrats proposing the legalization of cannabis as well allowing those who have been arrested for possession and/ or use to petition the court and have their records expunged.

Gov. Tony Evers’ proposed budget from 2021 also shows the economic impact of marijuana legalization. The budget factored in a tax on cannabis, estimating that $165 million would be generated in state funding from the sale of the drug.

Because of this potential for profit, commercial interests are a part of its long history.

“Commercial interests always impact commodities such as canna bis, whether that’s in the biomedical or personal use domains,” Richert explained. “The real questions in my mind have to do with the novelty of new cannabis healthcare products, as

well as their safety and e cacy. Are they being regulated well enough? Are the products ‘quack’ medicines? Are the e cacious ones available to the people who need them?”

Richert referred to the Scheduling of a substance, and how it a ects mul tiple aspects of society, including race. President Joe Biden has been working to address this as well.

In early October, Biden pardoned thousands convicted on federal charg es for possession of marijuana. He then released a video to Twitter saying “while white and Black and brown people use marijuana at similar rates, Black and brown people are arrested, prosecuted and convicted at dispro portionately higher rates.”

This event only adds to the exten sive history of marijuana in the United States.

“In 2020, I organized an online series of talks around the theme of cannabis,” Richert said about his work to inform students on campus. “That series was hosted by the UW-Madison School of Pharmacy and the American Institute of the History of Pharmacy.”

According to the UW-Madison School of Pharmacy, this lecture series was created after the DPPD decided that the history of cannabis had not been explored and taught as thor oughly as it should in medical and pharmacy schools.

The lecture series remains avail able online for students.

4 Thursday, November 10, 2022 dailycardinal.com

news

JAMES LUKASEVICS/THE DAILY CARDINAL

MEGHAN SPIRITO/THE DAILY CARDINAL

Federalization of Wisconsin Hemp Program opens doors, leaves some farmers wanting more

By Gavin Escott STAFF WRITER

Take a walk down State Street and you’re sure to see them — stores advertising products like CBD, Delta-8 and an assortment of other recre ational and medicinal items. While these stores can seem ubiquitous today, all of their products are actually relatively new, only having been legalized a few years ago.

What many of these products have in common is that they are derived from hemp, a class of cannabis with less than 0.3% tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the psychoactive component of the plant.

Hemp has a multitude of industrial and horticulture uses, ranging from fabric and construction materials to food products and cosmetics, but is most commonly known for the production of cannabinoids, such as CBD. It is distinguished from marijuana by the level of THC, which is too low in hemp to provide the same high.

The rise and fall of hemp in Wisconsin:

Despite it being legalized only three years ago, hemp and Wisconsin are no strang ers. In 1908, researchers in the University of WisconsinMadison’s agronomy depart ment, interested in learning about hemp as a source of fiber, harvested the state’s first hemp crop. UW-Madison continued further experimentation in sub sequent years, eventually con cluding that hemp was an excel lent source of fiber.

Encouraged by the univer sity’s success, neighboring farmers began planting their own hemp, according to the Leader-Telegram. Buoyed by a high demand for hemp fiber in the Midwest as well as fed eral promotion for hemp pro duction, crop production grew at an exponential rate. In 1915, Wisconsin farmers were grow ing 400 acres of hemp. Just two years later, this number had grown to 7,000 acres, and by 1920 the Badger State was the largest hemp producer in the United States, with more acres growing hemp than the rest of the country combined.

By the 1940s, however, the hemp industry had declined dramatically. With the excep tion of a brief spike during World War II, hemp was falling out of favor, and by 1948 the U.S. government got out of the hemp business — ending their pur chasing of hemp and the price support program. Coupled with decreasing demand and heavy restrictions, the hemp indus try limped on until 1957, when the last hemp crop was har vested in Wisconsin. In 1970, The Controlled Substances Act identified hemp as a Schedule 1 drug, prohibiting its produc tion and putting an end to legal hemp production in Wisconsin for nearly six decades.

“There was no hemp indus try before 2014 — it’s that sim ple,” said Rob Richards, the president of the Wisconsin

Hemp Alliance. “Any hemp that was in this country (fiber mate rial, etc.) was shipped in from countries like China and India.”

Rebirth:

The origin of Wisconsin’s current hemp program lies in the passage of the 2014 U.S. Farm Bill, which authorized the production of industrial hemp under state-run pilot programs for research pur poses. Despite the formal research, hemp remained a Schedule 1 Drug.

In 2017, Wisconsin estab lished its state Hemp Program, aptly named the Hemp Pilot Research Program. This program was helmed by the Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection (DATCP) and required farm ers and hemp processors to submit a research plan to become fully licensed as pro viders of hemp. In the first

“The legalization of hemp was not terribly smooth,” Richards said. “Now that hempderived CBD is legal, there still is no regulatory certainty when it comes to utilizing it in dietary supplements, food or beverag es. This has clearly hampered emerging hemp markets.”

What followed the transition was a swift and sudden drop in applications. In previous years, applications were high er than 2,200 per year, but in 2021 DATCP only received 1,337 applicants. More than a thou sand of 2021 applicants were returning — a 42% fall in the span of a year.

“The saturation of the CBD market after the 2018 Farm Bill was signed into law was prob ably the biggest factor in the drop in applications,” Richards said. “Growers are very good at growing hemp, but if you don’t have a more expansive market to sell your product, then you’re

turned program authority over to the federal Department of Agriculture. Today, Wisconsin farmers and hemp proces sors follow the final rule on hemp, which became effective in March 2021. According to the Shepherd Express, the DATCP hemp program was discontin ued when the transfer hap pened, and the services they provided, such as the hemp sampling service, are now pro vided by the private sector.

To Samuel Santana, the owner and founder of Wisconsin Growing Company, a lack of inspectors has been the most noticeable impact of federaliza tion. Previously, DATCP pro vided licensed inspectors who tested the hemp to ensure the plant didn’t contain more than 0.3% THC — the legal limit to be considered industrial hemp. According to DATCP, licensees are now responsible for finding their own sampling agent and

required. Processors still need to abide by state and federal safety laws, but there is no spe cific hemp license tied to it.

According to Richard, the removal of the state “Certificate of Commerce” has impacted processors tremendously since they could use the paper to prove their product was cred ible, particularly when it came to transportation. He said pro cessors have become inventive by using QR codes and other methods to protect themselves and their products.

One of the biggest chang es with federalization is that growers now have to work with the Farm Service Agency in Wisconsin rather than reach out to DATCP. Richard said the absence of DATCP cus tomer service was likely the most significant loss for grow ers and processors.

Still, Santana stressed that the Department of Agriculture has been helpful, particularly with communication and its simple process.

“They ask a lot less than they should,” Santana said, though he recognized the process wasn’t designed to be exclusive. “I also understand that they are not try ing to weed people [out]. They’re looking for a reason to approve people, not to deny people.”

However, Santana made a point to mention there were some policies he disagreed with, such as individuals with convic tions not being eligible to receive a license. Santana, who received his license on the 2018 Farm Bill, highlighted the irony of the situ ation: even though hemp is now legal, people formerly charged for hemp-related o enses aren’t able to participate.

Ultimately, though, Santana said he welcomed federal hemp regulation as it opened up oppor tunities in banking, financing and interstate commerce that used to be closed when each state had di erent laws.

year of the program, 347 peo ple applied for a license to grow or process hemp. The next year, application num bers ballooned with DATCP receiving 2,227 applications.

A year later, the 2018 Farm Bill legalized hemp federally and directed the USDA to estab lish a permanent federal hemp program. Individuals would now be allowed to grow hemp legally as long as their state had a federally approved plan, and the state pilot programs would begin phasing out.

Fast forward to October 2020, the Department of Agriculture hadn’t approved the plans of 23 states, including Wisconsin, with the Oct. 31 approval dead line looming.

At the eleventh hour, Congress passed an act that extended the 2014 Farm Bill until September 2021, but by that time DATCP had already transitioned Wisconsin to a new hemp program — essen tially an updated, functionally similar version that dropped the “research” and “pilot” parts of the title, according to Richard.

going to have a glut of product in the system.”

He said the initial spike in applications was attributable to Wisconsin’s “long and proud” history with hemp as well as farmers’ desire to diversify to mitigate risks.

“Early on many dabbled in hemp out of curiosity or just to see if they could make some extra money,” Roberts added. “Many got out because they couldn’t sell their raw material and couldn’t sustain year-overyear losses.”

Finances seemed to be the driving factor behind Wisconsin’s decision to give up its program. A Legislative Fiscal Bureau report from June found that Wisconsin’s hemp program was going to end the year with a negative bal ance of $450,000, and the State Legislature refused to provide additional funding. DATCP suggested doubling applica tion fees to increase income but decided against it, choosing instead to relinquish the pro gram to the federal government.

Finally, in January, DATCP

laboratory testing facility.

“We’d call [DATCP] and they would send somebody to us,” Santana told the Cardinal in March. “Now we need to find a licensed inspector, but since it’s so early, there are none.”

However, Santana expressed his optimism that the situation would improve in the coming months.

“It’s just this transition peri od,” Santana said. “I have no doubt that that’s going to get sorted out really quick.”

Last winter, when DATCP put out a call for licensed inspectors, there were only two USDA-certified hemp inspec tors in Wisconsin. When the Cardinal spoke to Santana in March, there were 49 USDAcertified sampling agents in Wisconsin — a number that has only increased since.

Changes because of the shift to USDA authority include the discontinuation of hemp licensing fees for farmers and changing the requirement to renew a hemp license from yearly to every three. A pro cessing license is also no longer

“All of these things — just boom — a bunch of doors open,” Santana said. “Once it’s federal you stop having the limitations of state. So let’s say if I want to buy a farm, using USDA money, or financing for a hemp farm. Now, it’s easier for me to do that.”

Richard said DATCP sought out the Wisconsin Hemp Alliance’s opinion on making the switch, noting that “we were aware of the move from day one.” He added that they worked together to ensure a smooth transition — setting up webinars, Q&As and connecting growers with resources at USDA.

Overall, Richard said the switch from the hemp pilot program to the USDA program went smoothly.

“I think there are pros and cons behind every deci sion but this one made perfect sense for Wisconsin,” Richard said. “Other states are now following Wisconsin’s path, and I have to believe many more will eventually make the move to USDA.”

news

dailycardinal.com Thursday, November 10, 2022 5

COURTESY OF GOODMOODFARMS VIA WIKIMEDIA

Overturn of Roe v. Wade invokes questionsaround emergency contraception access

By Annika Bereny STAFF WRITER

Content warning: This article contains mentions of rape and sexual assault. If you or someone you know has been sexually assaulted and is seeking help, contact the National Sexual Assault Hotline at (800) 656-4673.

University of WisconsinMadison junior and Sex Out Loud engagement coordinator Mia Warren is candid about her use of emergency contraceptives despite its stigma. The pill is her safety net when intimacy plans don’t unfold as expected.

“I’ve used Plan B quite a cou ple of times in my life for many di erent reasons,” Warren said. “One being I potentially missed a birth control pill and I wanted to be extra safe. I also used it in a relationship where he refused to use protection and wouldn’t allow me to use them either.”

Warren isn’t alone in her decision. Approximately one in four sexually active women between the ages of 20 and 24 have used emergency contracep tives before, according to a 2019 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention survey.

Emergency contraceptives assumed an outsized role in reproductive care following the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v. Wade in June, which made abortion virtually illegal in Wisconsin.

Consumer demand for emergency contraceptives rose as women looked to stock up on the tablets as a safeguard against potential pregnancies they would no longer be able to terminate. It skyrocketed to the point where retailers like CVS, Rite-Aid and Amazon placed purchase limits on emergency contraceptives, according to CNBC.

Those limits have since been lifted as suppliers have been able to meet the demand for emer gency contraception. However, with conservative politicians in some states contesting contra ceptive access rights in the wake of the Supreme Court’s decision, reproductive health advocates and lawmakers alike worry women may lose another vital reproductive care resource.

Wisconsin state senator Kelda Roys (D-Madison) rec ommends stocking a supply of emergency contraceptives as a safeguard against potential future access barriers.

“It’s not something where you should have to drive around to a pharmacy or find a hos pital that will dispense it,” she said. “Just like when you have a headache, you don’t want to be driving to the store. You want to have Tylenol already, same with emergency contraception.”

Explaining emergency con traceptives

While preventative in nature, emergency contraceptives are often caught up in the debate over abortion because of because of the misconception that they can stop an already-fertilized

egg from developing into a fetus.

In actuality, the pills pre vent pregnancy by inhibit ing ovulation, according to the World Health Organization.

things about sexual assault is that you don’t have control over what is inflicted on your body,” State Sen. Roys said. “We can help empower people who are

In response, the Legislature gaveled in and gaveled out of the special session in under 30 seconds.

This was yet another attempt

our healthcare system and our doctors, but Republicans chose to do nothing.”

Where to get it: Emergency contraceptives on and o of UW’s campus

UW students can still pur chase emergency contraceptives despite their uncertain future.

Both Union South and Memorial Union’s Badger Markets o er a generic form of Plan B — the EContra EZ pill — for $13. Students can also access Plan B at local pharma cies, including Walgreens, with out a prescription, and Walmart carries emergency contraceptive tablets for as low as $8.

While Plan B has become almost synonymous with the concept of emergency contra ception, other options exist for different body types and urgency levels.

Emergency contraceptives do not induce abortions nor can they harm a developing embryo in a pre-exisitng pregnancy.

Despite that, though, the rhetoric of life beginning at the point of insemination is per vasive. One of the most preva lent arguments against abor

victimized to become survivors is to give them back that agen cy that was stolen by o ering emergency contraception.”

Emergency contraception is currently o ered to rape vic tims upon request in Wisconsin emergency rooms, thanks to the 2008 Compassionate Care for Rape Victims Act. Roys wor ries hospitals could revoke that support if laws are changed in the wake of the Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision.

by Democrats to put the ques tion of abortion on the ballot for Wisconsinites in the hopes that a referendum could do what they have been unable to do in the past few years with a Republican-controlled legisla ture — cement abortion rights into Wisconsin’s constitution.

Another brand, ella, can be used up to five days after sex. Ella works best for those between 165 and 195 pounds unlike Plan B, which is most effective under 165 pounds. However, ella requires a prescription and is pricier than Plan B, which is available over the counter and without age restrictions.

tion relies on the belief that life begins at conception.

In 2021, the Missouri Senate voted to ban using taxpayer funds towards intrauterine devices (IUDs) and emergency contraception, according to the Missouri Independent. Missouri State Senator Denny Hoskins (R-21) claimed emergency con traceptives, too, take e ect after the conception of a child.

Hoskins’ statement exem plifies a common misconcep tion about the actual function of emergency contraceptives, according to Warren.

“Sperm can set in di er ent places for multiple days,” Warren said. “That completely contradicts some religious per spectives that are like as soon as you’re inseminated, there’s baby making happening. Realistically, that’s not how it always works and that’s why Plan B is so important.”

The importance of emergen cy contraception is imperative for those unable to control the use of contraceptives during intercourse, Warren argues. For victims of sexual assault, emergency contraception can be helpful for those looking to regain a sense of control over their bodies and prevent a pregnancy.

“One of the most traumatic

And, while important to survivors of sexual assault, Warren said that emergency contraception should be avail able for all to use without stig ma. She and other members of UW-Madison’s Sex Out Loud are working to dismantle closed rhetoric around sex education.

“I guess we’re still trying to live in this abstinence only realm, which just isn’t realistic,” she said. “I don’t think I know a single person that hasn’t used the morning after pill, which is a lot of people.”

Whether using it out of necessity or not, emergency con traceptives are one of few ways women can exert control in an inherently uncontrollable situa tion, according to Warren.

“I always felt empowered when I was able to make that choice,” Warren said. “Maybe I should have been using bet ter protection, but life happens. As a 16-year-old girl who didn’t have a good sex education, I went about my options the only way I knew how.”

A statehouse battle over con traceptive rights

While Sex Out Loud is fight ing to make contraceptives accessible on UW-Madison’s campus, a similar fight over reproductive rights is hap pening just blocks away at the State Capitol.

Democratic Gov. Tony Evers called the Republican-controlled Legislature into special session on Oct. 4 in hopes of putting Wisconsin’s abortion ban to a statewide referendum vote.

Roys and Rep. Lisa Subeck (D-Madison) tried to repeal Wisconsin’s 1849 abortion ban in January 2021 with the Abortion Rights Preservation Act, over a year before Roe’s overturn.

Republicans made sure the bill went nowhere, accord ing to Rep. Deb Andraca (D-Whitefish Bay).

“We had over a year to have a hearing on that bill,” Andraca said. “Even if we didn’t advance it as written, we could have had a discussion. We could have had some sort of a compromise and at the very least clarified where we stood in this state.”

Since then, Evers has been the sole guard against Republican attempts to regulate reproduc

Planned Parenthood Advocates of Wisconsin pro vides patients with multiple contraceptive options, including ella, at their 2222 S. Park St. loca tion in Madison, according to spokesperson Lisa Boyce.

“It really is important that you take a method of emergency contraception that works best for your body and your circum stances,” Boyce said.

Planned Parenthood Wisconsin currently provides free ‘Make-a-Plan’ kits at all 22 health centers around the state. The kits contain a morning after pill, pregnancy test, condoms and information about threats to abortion access.

“Though the future of emer gency contraception will likely stay secure in Wisconsin follow ing Gov. Tony Evers winning reelection in the 2022 midterms, Boyce emphasizes its cur rent availability and Planned Parenthood’s continuing com mitment to making it available to Wisconsinites.

tive services. The Democratic governor vetoed bills like SB 593, which aimed to block abor tions because of fetal anomalies.

Andraca said Wisconsin Democrats will continue their e orts to restore reproductive rights in Wisconsin to their preDobbs capacity.

“We need a public hearing on these bills so that we can even just start to discuss it,” Andraca said. “We could have been trying to do something in Wisconsin to protect women,

“No one should fear com ing to Planned Parenthood to access information about abortion, miscarriage, or any other health care needs they may have,” she said. “We are a safe and confidential place for people to get information about all their healthcare resources, without judgment.”

Warren encourages anyone in need of emergency contra ceptives to seek out resources, especially since the stakes of an unexpected pregnancy are high er than ever before.

“I’m here living my dream, working with Sex Out Loud and having a future,” Warren said. “If I would have gotten pregnant in high school, which I know happens for a lot of people, my life would look really

6 Thursday, November 10, 2022 dailycardinal.com

NEWS

di erently right now.”

LAUREN AGUILA/THE DAILY CARDINAL

Plan B is just one emergency contraceptive option that lines shelves today, though access to these resources is contentious.

Kelda

Roys Wisconsin State Senator (D)

“We can help empower peo ple who are victimized to become survivors ... to give them back that agency that was stolen from them.”

Deb Andraca Wisconsin Representative (D)

“We could have been trying to do something to protect women, our healthcare sys tem and our doctors, but Republicans chose to do nothing.”

UW-Madison has a binge drinking problem

By Claire LaLiberte STAFF WRITER

By Claire LaLiberte STAFF WRITER

The University of WisconsinMadison is consistently ranked among the top “party schools” in the country, a qualification that often goes hand-in-hand with a school’s drinking culture. That is certainly true at UW-Madison, the nation’s number one school for beer con sumption, and many students feel this reflected in its atmosphere.

According to an undergraduate student who chose to remain anon ymous, being a sober individual at UW-Madison can be challenging and othering. The university is so synony mous with heavy drinking that she said she has been asked many times why she would choose to attend it as a non-drinker.

“I have had people pressure me to drink [... and] pry excessively about why I don’t,” the student said. “I feel you can definitely exist at UW as someone who is sober, but be prepared to be shunned or mocked for sure.”

Social Drinking Culture

According to a 2016 study pub lished in the Wisconsin Medical Journal, 65% of freshman students reported drinking — but that number increased dramatically in the years following, with nearly 85% of sopho mores and juniors reporting them selves to be drinkers.

This seems to indicate something many UW students reported: an envi ronment in which drinking feels like a social necessity. In 2015, UHS first conducted a study called the Color of Drinking, in which 90% of students described the university’s drinking culture as negative and many report ed feeling pressured to drink.

The study also found that of those who were considering leaving the uni versity, 20% of students of color and 30% of white students reported the alcohol climate to be the driving factor in that decision.

Undergraduate student Ingrid Szocik said her abstention from drinking “made [her] feel like [she] didn’t belong at this university, in this city.” Because of the alcohol-centric culture, Szocik stated that “[she] could not picture [herself] living [in Madison] long-term.”

Jenny Damask is University Health Services’ assistant director of high-risk drinking prevention. She urged students who do drink to examine their own habits in order to “work towards a healthier, more inclusive environment.”

“It becomes really di cult to navi gate if everyone feels like they’re con necting over this alcohol-fueled envi ronment,” said Damask, adding that building a community sober students can comfortably navigate requires drinkers to examine their relationship with alcohol and how they behave when under the influence.

Kaitlyn Andrews is a sophomore who also chooses to be sober, and she said she has rarely been pressured to drink. However, when attending social events where others are drink ing, she said being sober makes her feel that she will “never be a full part of the group.”

In UHS’s 2017 Color of Drinking study, 42% of students interviewed were found to be high-risk drinkers, compared to 27% of undergradu ate students nationwide. High-risk drinking contributes to alcohol-relat ed crime — as of 2017, UW-Madison ranked eighth nationwide for quantity

of drinking arrests.

The state of Wisconsin itself leads the nation in alcohol abuse, with its rate of adult binge-drinking 50% higher than the rest of the country. A 2021 study found that every single county in Wisconsin qualified as a “heavy-drinking” county, and of the top 50 heaviestdrinking counties in the country, 41 were in Wisconsin.

Connor King cited UW-Madison’s drinking culture as the main reason he chose to drop out of the univer sity last year. According to King, even being a purely social drinker can still equate to two or three nights of hard drinking a week, and it wasn’t until he “left the university that I realized how unhealthy, yet common, these habits are.”

King said that incoming students are in vulnerable positions, likely experiencing anxiety and a sense of urgency to make friends.

“With a drinking culture as per vasive as UW-Madison’s, students may lean on substance abuse both as a means of comfort and as a way to find friends through the social scene,” said King.

The normalization of alcohol abuse led King to develop unhealthy drinking habits, which eventually became “full-fledged alcoholism and substance abuse of other kinds,” ren dering it impossible for him to con tinue his academic career, he said.

“While this is a more extreme example of the damage that the drink ing culture at UW-Madison can inflict, I am not an outlier,” said King. “There are many other stories like mine. It is so easy for students to be lulled into these habits of alcohol abuse that they don’t realize it’s a problem until it’s too late.”

Cost of Binge Drinking

A raid conducted on a State Street bar earlier this year provided a shock ing demonstration of the proportion of drinkers who are underage — of the 143 people present, only six were of legal drinking age.

Unhealthy drinking habits corre late with poor mental health. Damask said alcohol abuse often stems from underlying mental health issues that need to be addressed first in order for one to recover.

Damask emphasized the ways in which di erent issues and identities intersect, saying that “it’s really hard to look at things in a vacuum.” She urges students with concerns about either mental health or substance use to look at how their relationship to each relates to the other.

In situations where students are illegally drinking but need medical help, the University of Wisconsin Police Department (UWPD) has a policy in place called Medical Amnesty through Responsible Actions. According to a first-year student who chose to remain anon ymous, the amnesty policy doesn’t always save concerned friends from legal repercussions.

This student said he was with a group when one of his friends began exhibiting symptoms of alcohol poi soning, so he asked a passerby to call 911. When UWPD arrived on the scene, they told him he was not eli gible for amnesty because he hadn’t placed the call.

The anonymous student said his takeaway from the event was “that calling for help with someone with alcohol poisoning will cost you about $400” in fines and associated fees. He

added that “the school is not transpar ent whatsoever about this when talk ing about the amnesty policy.”

UWPD could not provide com ment on this incident, but referred to the guidelines of the amnesty policy. The department neglected to respond to questions regarding UW-Madison’s levels of alcohol abuse and how a safer campus community can be created.

Whereas some students, like

Andrews, don’t feel explicitly pres sured to drink, others see that pres sure as implicit in the culture at UW-Madison. King expressed that “there’s not usually any pressure to drink from friends, as it’s more of an unspoken thing.” He found that “if I wanted to spend time with my friends, it would likely be drinking.”

The monetary toll of heavy drink ing is also significant, and it means

that indulging in the school’s drink ing culture may require either financial privilege or sacrifices. Gus Wehrs, who completed undergrad at UW-Madison in 2021 and is currently pursuing a Master’s, expressed his resentment for the privileged “tailgate game-day culture.”

According to Wehrs, who said he worked 40 to 50 hours a week to make ends meet during his undergradu ate career, “being able to buy football tickets, grill out [and] pound cheap cases of beer is a luxury.”

Therese Wright started at UW-Madison in 1981, when the drinking age in Wisconsin was 18. She emphasized that though it was common for undergraduates to go to bars and parties, binge drinking was not common.

“In my experience it was a rare occurrence that I would see some one binge drink to excess, to the point of vomiting or passing out,” Wright said.

Wright attributes this to the fact that “alcohol was available and acces sible” at that time, whereas “today it seems as though students will abuse alcohol when they are able to get access to it.”

The opioid epidemic: How Wisconsin plans to fight back

By Lara Hagen STAFF WRITER

A purple, seemingly harm less flower, has cost many people their lives despite its inconspicu ous appearance. Originally used for medicine, the poppy plant was mankind’s first painkiller.

The first record of the use of the opium poppy plant comes from the Sumerians of Mesopotamia. At that time, the flower was known as the “joy plant,” as the body immediate ly felt a kind of euphoria upon consumption. Later, however, in addition to its medicinal benefits, it became the main source of nar cotics such as morphine, heroin and codeine. It grows mainly in the Mediterranean region, but with the spread of narcot ics around the world, the opium poppy plant has matriculated into many di erent countries, driving a countless number of people into deep addiction.

Especially in the United States, opioid abuse became a national problem. The Department of Health Services (DHS) and Wisconsin politicians are now teaming up to tackle the crisis. A nation in crisis

The death rate due to drug abuse has steadily gone up in North America since the 1990s. In 2017, two thirds of deaths attrib uted to substance abuse were due to opioid abuse. In absolute num bers, nearly 47,600 people died in 2017 from opioid abuse. Since 1999, 500,000 deaths can be attributed to the same cause.

There were multiple triggers for a health crisis of this magnitude.

In 1999, the pharmaceutical industry in the U.S. promot ed opioids as an all-purpose weapon against varying lev els of pain, prompting doctors

to prescribe them more often. This paid off: the number of prescriptions for such painkill ers has quadrupled since 1999. According to the U.S. Attorneys Association, prescription drugs are the second most addictive substance after alcohol.

One driving factor that pushed up opioid use was the rise in pharmaceutical industry market ing at the turn of the millennium, according to the National Library of Medicine. In particular, “Purdue Pharma,” the manufacturer of OxyContin, intensely pushed the marketing of painkillers, invest ing over $200 million in 2001 alone. OxyContin is a treatment for pain severe enough to require long-term daily opioid treatment, according to the CDC. The risk of addiction is extremely high.

The second wave of opioid deaths came in 2010 with the expansion of the heroin market in the U.S. After it became clear that the requirements for prescribing painkillers would have to become stricter, people who were already addicted sought a new alternative, and found it in heroin.

Heroin is cheaper to obtain than prescribed opioids because it can only be purchased on the black market. In addition, the e ect is stronger because the prescribed opioid is often stretched, whereas illegally sold heroin can be much purer and therefore stronger.

A third wave hit the U.S. when the use of “synthetic opioid” became more common.

Synthetic opioids are substanc es synthesized in a laboratory. These agents were developed to achieve a joke-relieving e ect in humans like natural opioids such as morphine or codeine. Some types of man-made opioids are approved for use in medicine, but

illegal versions began to be traf ficked from the 1970s. The illicit substances are believed to be man ufactured abroad and brought into the U.S. with the largest imports from Mexico and China.

Opioids in Wisconsin

The opioid crisis hit Wisconsin as well. Between 2014 and 2020, alcohol was the state’s most com monly used drug, followed by marijuana. However, opioids still caused the majority of drug abuse deaths and hospitalizations, according to the DHS.

From 2018 to 2020 alone, the death rate from opioids in Wisconsin increased by 46%. Because of cocaine containing syn thetic opioids, the death rate in Wisconsin between 2019 and 2021 has increased by 97% — from 651 to 1280 deaths.

The scope of opioid abuse also varies among Wisconsin counties.

The areas most affected by the epidemic are primar ily in the southeastern part of the state. In 2020, the counties of Kenosha, Walworth, Rock, Racine, Milwaukee, Waukesha, Washington, Dodge, Sauk, Sheboygan, Fond du Lac, Adams, Juneau, Jackson, La Crosse, Winnebago, Manitowoc and Vilas all experienced abuse rates above 18 per 100,000 residents, which is considered high, according to the DHS.

Milwaukee fares the worst in these statistics, as the coun ty had an opioid death rate of 44.6 per 100,000 residents. Dane County is also listed among the counties most a ected by the opioid epidemic. The death rate per 100,000 residents was 23.1 in 2020, and most of the deaths happened to be people between the ages of 18 and 44.

news dailycardinal.com Thursday, November 10, 2022 7

MADI SHERMAN/THE DAILY CARDINAL

Readmore@dailycardinal.com

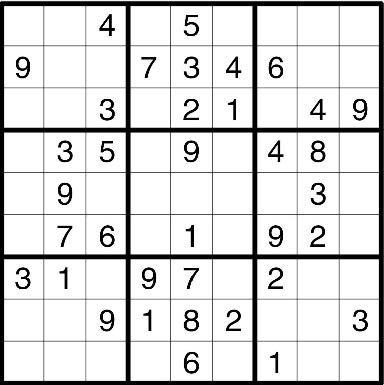

Mapping The Drug Issue

UW-Madison

Could psychedelics be the healthcare of the future? UW researchers find promising results

UW-Madison

UW-Madison

By

Ethan Wollins Opinion, p. 13

By Sarah Eichstadt City News, p. 3

Noe Goldhaber Science, dailycardinal.com

By

By Annika Bereny State News, p. 6

Concussions, excessive use of painkillers blemish football’s image By Dylan Goldman Sports, p. 11

By Madeleine Afonso Campus News, p. 3

By Gavin Escott City News, p. 5

special pages 8 Thursday, November 10, 2022 dailycardinal.com

The failure to adapt to underage drinking

Sheboygan Overturn of Roe v. Wade invokes questions surrounding emergency contraception access

decriminalized?

Madison Is it

Clearing up the confusion about marijuana policy in Madison

Milwaukee Federalization of Wisconsin Hemp Program opens doors, leaves some farmers wanting more

UW-Madison UW-Madison students find community in collegiate addiction recovery program

Campus

Alcohol Psychedelics Marijuana/Hemp Opioids Birth Control KEY:

Milwaukee The opioid epidemic: How Wisconsin’s plans to fight back By Lara Hagen Features, p. 7

Initiative

Male contraception: Why is there still no pill for men?

By Lara Cathleen Hagen STAFF WRITER

The topic of contracep tion is often seen as a “wom en’s issue” because women are often the ones who bear the burden of pregnancy. However, there is another side to the equation — the development of a male birth control pill has a rocky past, but a hopeful future.

One of the best-known contraceptives on the mar ket is the birth control pill, colloquially known as “the pill.” It is reasonably a ord able, very easy to use and very e ective. What most people don’t know is that the female contraceptive pill was launched in 1957 under the name “Enovit” in the United States. At first, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the pill for a com pletely different purpose, namely, to treat menstruation disorders such as irregular menstruation and premen strual syndrome (PMS). A few years later, in 1960, the pill was available for purchase as a “contraceptive” for the first time. This sudden easy access to birth control was an enormous gain in freedom and peace for women of the 1960s. At the time, women in the U.S. did not have access or knowledge of birth con trol, and would often resort to dangerous or unreliable alter natives. The pill changed this situation significantly.

Nurse and women’s rights activist Margaret Sanger made a major contribution to the development of the pill. Around the 1920s, it was still almost universally forbid den to talk about contracep

tives in the U.S. because of the Comstock Act — a federal law from 1873 to “suppress the trade in and distribution of obscene literature and articles with indecent content.” Margaret Sanger fought against this law by making information about birth control and contracep tives available to women. She was arrested in 1916 for open ing the first birth control clinic in the U.S.

Much has happened since the first pill appeared on the market. There are now count less di erent birth control pills, all of which work in roughly the same way: the pill mainly contains the hormones “estrogen” and “progestin,” which prevent ovulation. No ovulation means no egg can form with which the sperm could possibly combine. Thus, fertilization — and pregnancy — is prevented.

The pill seems to be an all-too-perfect means of birth control — if it weren’t for the countless and some times extremely severe side effects. The list is long: bleed ing disorders, nausea, bloat ing, weight gain, psycho logical impairments such as depression, breast tender ness, headaches, dry vagina, cysts on the ovaries, reduced desire for sex, increased risk of thrombosis, deeper voice, more facial hair, acne and more — and about 88% of all women who take the pill suf fer from at least one of these side effects.

Women are already tak ing on many side effects. But, why do we only talk about women in regard to this topic? It takes two people for a pregnancy, so we should

also ask ourselves what birth control would be possible for men. Currently, there are only two methods of contra ception for men: vasectomy and the condom. But what about a pill for men?

The concept, which is being tinkered with, works in basically the same way as for women: By taking more testosterone, the hormonal balance in the man is altered so that he produces fewer sperm — so few, in fact, that it is no longer possible to father babies. The problem is that the male body, unlike the female body, immediately breaks down the excess tes tosterone, so it does not even reach the vas deferens. The testosterone would have to be injected directly into the vas deferens with a syringe, but this is unpleasant and not easy to handle. Likewise, men would have to get this injec tion from a doctor.

Some studies on male con traceptive methods started in the 1980s. The World Health Organization (WHO) has been researching a “gel” that contains testosterone and norethisterone, and is inject ed with the help of a syringe.

Every eight weeks, sub jects were given a dose of the hormone cocktail which made them infertile, and the effect lasted only until the injection was no longer taken. However, the study of the WHO was stopped in 2011. The reason: too many side effects, including depression, weakening of libido and weight gain. Does this sound familiar?

Continue reading at www. dailydardinal.com

Vikings might have gone berserk with magic mushrooms

By Joyce Riphagen STAFF WRITER

Humans have likely been using substances since before we were truly humans — alcohol metabolism appeared in nonhuman primates up to 21 million years ago, and plenty of other animals, from dolphins to moose, are known to partake in what we may call “drugs.” Drug use is a part of life for many species and has been for a long time.

The field of ethnobotany, which studies the ways in which humans and plants interact, focuses partially on this aspect of human history. Among other uses, such as food, art or building, ethno botanists study how humans have historically used plants as medicinal or recreational drugs as well as how we con tinue to do so today.

A striking example of drug use in human history is that of viking berserkers, legendary warriors whose trance-like fury in battle was unmatched. There are many theories of how berserkers (whose name literally trans lates to “bear-shirts”) entered this ritualistic rage — some suggest that it was a selfinduced hysteria, while oth ers think it could have been the e ects of PTSD caused by years of exposure to violence.

Yet, some historians have another theory — the berserkers took psychedelic mushrooms.

Amanita muscaria, com monly known as the fly agaric, is the first “magic mushroom” many people think of. With its charismat ic red cap and white spots, Amanita has earned a place in pop culture as the emblem of psychedelics, though in fact it is not used nearly as often as other psychotro pic mushrooms, as it does not produce psilocybin. A. muscaria is native to tem

perate and boreal regions in the Northern Hemisphere, and its psychoactive e ects are due to two compounds: ibotenic acid (a neurotoxin that acts on the brain’s glu tamate receptors to produce an excitatory e ect in the nervous system) and musci mol (a psychoactive chemical that can produce sedativehypnotic, depressant and hallucinogenic activity).