i

ii

THE ANA \THƏ\·\Ā-NƏ\ PRONOUNCED: AH-NUH (NOUN) 1. A collection of miscellaneous information about a particular subject, person, place, or thing. 2. The Ana is a quarterly arts magazine that celebrates humanity. We act and publish in line with the notion that everyone’s life is literature and everyone deserves access to art. While all rights revert to contributors, The Ana would like to be noted as the first place of publication. The Ana acknowledges that this magazine was founded on the unceded ancestral homeland of the Ramaytush Ohlone peoples, who are the original inhabitants of the San Francisco Peninsula. We acknowledge the painful history of genocide and forced occupation of their territory, and we actively seek to honor and respect the many diverse indigenous people connected to this land on which the magazine was founded. And we honor the fact that they are still existing on this land, and deserve to thrive. If you live in the San Francisco Bay Area, we encourage you to pay an annual Shummi Land Tax (via the Sogorea Te’ Land Trust) or to find a way to aid in the redistribution of land sovereignty to Indigenous folks. Cover design by Minhee Kim & London Pinkney Cover texture by JZ Creative Space. Typesetting and design by Carlos Quinteros III & London Pinkney Set in Georgia (Matthew Carter, 1993), Futura (Paul Renner, 1927), Krungthep (Susan Care, 1984) iii

iv

THE ANA presents

ISSUE #12 Spring 2023

v

EDITOR’S NOTE Summer is on the horizon as The Ana heads into the second half of her third year. It still feels surreal publishing all the beautiful art and necessary writing that have filled the pages of our last eleven issues. Although, at times, it was not easy. From ensuring we have enough funds to print our yearbooks and hitting deadlines so the artists and writers could witness their work navigate the world and finding places to host our electric events, here we are on the eve of releasing the 2023 Yearbook with no signs of slowing down. As we continue to gain ground, I want to take this opportunity to remind everyone about the understanding and empathy we all generously gave each other during the pandemic. As things return to whatever normalcy there was before the pandemic, please continue to spread patience and care throughout your communities and to those who may need it. Just because there isn't a global pandemic doesn’t mean we stopped needing time to organize and process the events in the world and our personal lives. Also, as we head into our fourth year (!!!!), I want to take this opportunity to meditate about “gaining ground.” What does it mean to gain ground? Are we taking space away from others to carve out our space in the world? Obviously, I do not think this to be true, but rather we are gaining the ground lost in our voices and expression collected in our issues and events. Gaining ground for us here at The Ana is about reclamation, not capturing something that is not ours. See, as I prepare to graduate from the MFA program at SF State, I am determined to understand my footing on this earth and where I stand in the different groups and communities, I am a part of. Where do I go after this? It is a question I ask myself constantly. It brings me stress, panic, and fear. It sweeps the floor beneath me until I am curled up in my bed, wishing that the world could just stop for a second so I can have one clear thought without the weight of doubt on my shoulders.

vi

I am not here to answer how to get out of this headspace, but rather reiterate how much The Ana means to me and express how much I hope it means to you. In my times of weakness and doubt, The Ana becomes a map of lives and experiences that remind me of the humanity nestled inside the chest of each of us. It reminds me of where I have been, what I have survived, and what I cherish. The Ana has become a lifesaver for me, and I hope it does the same for you, the reader, and you, the artist and writer, because we all need each other on this old ground, we are reclaiming together. A space beyond the text. A space where we can celebrate the work put into the craft and understanding our positionality in the literary space.

Carlos Quinteros III MANAGING EDITOR & POETRY EDITOR

vii

CROSS GENRE LITERATURE 65

Andres Had Always Wanted a Dog by Daniel Gonzalez

FICTION 1

Wrecked Remnants by Robert Pettus

39

What Would Khadijah Do? by Akasha Neely

50

I Love You Also, I Promise by Sophia Quinto

76

Fucked in the Name of Empire; or, Death to Fucking America by Akasha Neely

NONFICTION 24

in the poet’s house, i am the mirror by Erick Sáenz

90

To The Hardware in My Leg by Lujan Al-Saleh

POETRY 23

Deac by Elisha Taylor

37

On Turning 17 by Alexandria Wyckoff

49

February by Abigail Pak

64

On TV There Are Two Women Kissing by Elodie Townsend

94

Vandals by Elodie Townsend

97

shell by Kwame Daniels

98

Aspen Vista Blue Pt. 1 by Jesse Strohauer

VISUAL ART 36

Words on Fire by Karen Gomez

viii

38

The Condor’s Cove by Violet Bea

63

Smoke Break by Violet Bea

75

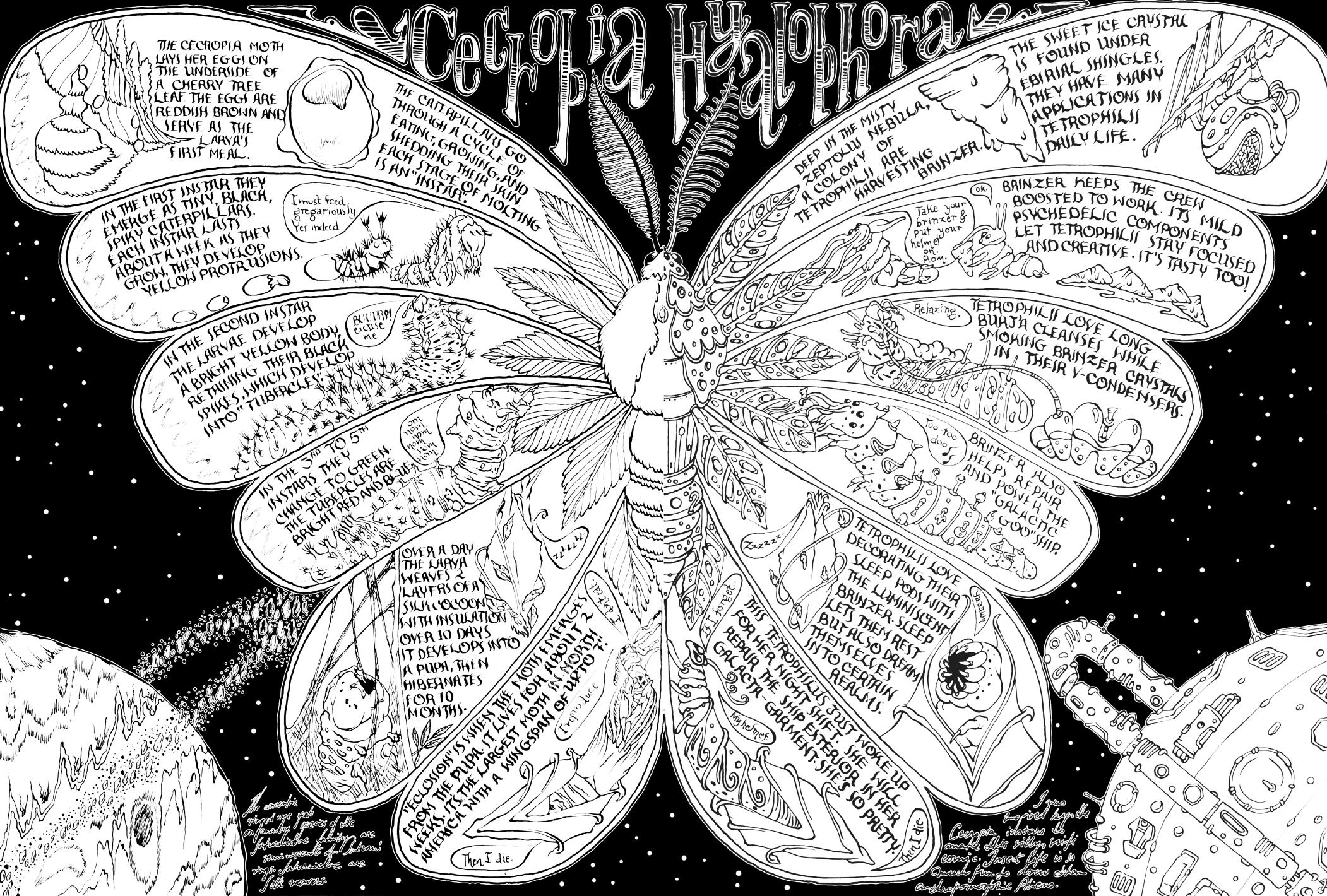

Cecropia Hyalophora by Violet Bea

88

T.P.T. by Brielle Villanueva

89

El sol y la hierba by Brielle Villanueva

96

MetaCarpal by Violet Bea

99

What A Joy To Be Beloved by Jesse Strohauer

. . . . . . 10

The Serious Business of Childhood a conversation with Christine Ferrouge

100

Writing Through the Mutant Continuum a book review of Poetechnics: Designs from the New World by Yaxkin Melchy

104

ix

Contributors

Wrecked Remnants fiction by

Robert Pettus The outside world was unknown to her, but she could see a glimpse of it through the window in his room. She had never seen much of anything out there—it was like staring at a slightly mobile painting, one that changed only slightly each day—but she continued to peer into the curved glass of the scope anyway. “You need to stop wasting your time doing that,” said Mr. Greenwell, rocking on his wobbly stool, “Anything happens up there, you’ll know about it. I promise you that. You won’t be able to avoid it. This little bunker of ours, it’s only holding on by a thread. I’m surprised we’re still here, to tell you the truth—a decade is a hell of a long time to survive in this sort of situation.” “What else am I supposed to do?” said Alice, turning from the exteriortelescope and glaring backward at Mr. Greenwell, who sat comfortably on his stool, which was cushioned with an old, cut-out Styrofoam mattress-pad duct taped onto its brittle wooden surface. She grinned at him. He smiled back. He was her only real friend in the world, and she was likely his. Though he was so apathetic—that was a new word she had learned when reading in the library last week; apathetic—he just sat on his stool pointlessly all day, every day. Mr. Greenwell took a healthy smack from his vape, exhaling the fragrant vapors as smoke engulfed the small room. “This place is a cell,” growled Mr. Greenwell, scratching at the remnant, prickly gray hairs on his shiny bald head. “You say that every day. And you really need to quit smoking. I don’t know how the guards haven’t snagged that thing from you yet.” “It doesn’t even have any nicotine. I make the juice myself—what can they say about it? I’m doing nobody no harm. Plus, they should simply be happy I don’t lose my damn mind at not having a single cigar for ten years.”

1

“I’m sure your lungs don’t appreciate it,” said Alice, “And plus, since you make it yourself, why don’t you make it a little less…pungent?” Pungent was another word Alice had recently discovered. “I like the smell,” said Mr. Greenwell. “Anyway, what are you reading this week?” “Notes From Underground. Saw it in the library; it seemed fitting.” “Fitting, indeed,” said Mr. Greenwell, scratching at the creases on his wrinkly brow. “Why are you so dried up and flaky?” said Alice “I have psoriasis. No ointment in the hospital wing. They say the patrollers look for it when they go out—I put in a damned request, for that and cigars—but they haven’t found anything. I don’t think they even look. Bastards.” “Oh,” said Alice. She didn’t know what psoriasis was; she hadn’t learned that word yet. She made a mental note to uncover its meaning. She would ask Mr. Greenwell, but she didn’t like seeming uneducated; that was the paradox of self-education for the proud: questions were a double-edged sword. Alice felt proud that she so easily recalled the word paradox, though. Unable to intelligently respond, Alice instead looked back into the exteriortelescope. Exterior-telescopes—one of the only novel ideas of subterranean, post-End life, were tubes, stretching upward through the earth, which used a series of underground mirrors to see into the outside world—like a window. A window from underground into the “real” world. Alice stared at them incessantly, and she mostly used Mr. Greenwell’s, being that he was the only person she really trusted. Every morning, Alice would hop off her top-bunk in the adolescent dormitory and, after stopping by the library to gather her new books, run over to Mr. Greenwell’s room to see what was going on in the real world. Nothing much was happening today. She had seen a tumbleweed roll across the chalky dirt of the outside post-apocalyptic desert, bouncing into an unaware desert cottontail, which leapt around in instinctive, prey-like horror before realizing it was just a dry plant. The rabbit then began eating the tumbleweed, satisfied with the crunchy snack.

2

“Damn!” said Alice, removing herself from the lens, “As much as I love rabbits, I need some more excitement on the tube!” Encircling her left eye was a red ring, proof of the time and effort she expended staring into the scope. “You should watch your language,” said Mr. Greenwell. “You cuss all the time,” said Alice. “Yeah, but I’m old, so I’m allowed to say whatever the hell I want. You’re a young girl, so it’s not polite.” “No one gives a shit about that kind of stuff anymore; we’re at the end of the world, in case you hadn’t noticed.” Mr. Greenwell chuckled. Alice smiled at him. “So, what’s for lunch today?” said Alice. “Let’s see,” said Mr. Greenwell, removing the weekly news bulletin from the organizer on his wall and scanning it for the menu. “Looks like Salisbury steak with brown gravy, buttered peas, and mashed potatoes.” “We have that every week,” said Alice. “Peas are easy to preserve; Salisbury steak and mashed potatoes are easy to fake. It’s a pragmatic meal when you live underground.” “Well I’m tired of it!” yelled Alice, throwing her hands skyward. She was also wondering about the meaning of the word pragmatic. “I kind of like it, honestly,” said Mr. Greenwell. Alice smiled in concession, “I do too—I can’t deny it. There’s something about that mushy steak that just gets me.” Talking about food had worked up their appetites, so they decided to head out a little early for lunch. Alice grabbed Mr. Greenwell’s cane—an old, twisty thing with a rubber base—and helped him from his stool. They left the quiet of Mr. Greenwell’s room and entered a surprisingly bustling hallway. . . . . . . “The hell is going on today?” said Alice glancing back and forth at groups of people scurrying by frantically.

3

“Who knows,” said Mr. Greenwell, “Maybe they’re having a surprise Keno drawing; they’ve done that before. If so, we’re going to have to wait on lunch so I can get in on the action. The administration had recently begun using Keno as a sort of lottery to help create a bit of excitement and tradition for colony residents. It was a normal Keno game, but instead of money, the winners received additional access to goods like food, pillows, blankets, books, and board games. It had thus far been very successful. “Maybe you’ll win!” said Alice, who wasn’t yet old enough to participate, “Then you can snag that Connect Four game the patrollers found! Wouldn’t that be awesome?” “If I happen to win,” said Mr. Greenwell, “I’ll gladly purchase you the copy of Connect Four.” The two of them continued toward the cafeteria. As they pushed forward down the narrow hallway, they noticed in the expressions of passersby more terror and confusion than excitement. “I don’t think this is related to Keno,” said Mr. Greenwell. “Yeah. These people are acting crazy,” said Alice, “What do you reckon is going on?” Mr. Greenwell didn’t respond, but Alice could tell by his worried expression— which crinkled the lines on his wrinkly forehead—that he was nervous about something. “Let’s go to the cafeteria,” he said, “Somebody will be able to tell us what’s going on there.” The cafeteria was nearly vacant. Steaming trays of food sat unattended at the buffet. Mr. Greenwell noticed someone—a plastic-apron, hairnet wearing member of the kitchen staff—ducking from the main room of the cafeteria into the back room of the kitchen. “Hey!” said Mr. Greenwell, pacing over to catch up with her. His cane wobbled with each step as he leaned into it and pushed forward. “Hello, ma’am! I need some help!” Alice, grabbing a hardtack biscuit from a nearby basket, followed him into the kitchen. “I can’t help you, sir,” said the kitchen staff employee, worry induced sweats painting her leathery face. “You don’t know anything?” said Mr. Greenwell, “Nothing at all?” 4

“Only thing I know is what my boss told me, which was not to plan on coming back to work anytime soon. Something serious is about to happen; I don’t know what the hell it is, though.” Straining to bite into the crunchy biscuit, Alice bit off a chunk of the bread, chewing it aggressively. “A mystery!” she said, nudging Mr. Greenwell in his side, “We’ll get to the bottom of this, won’t we! Finally, some real excitement for a change. This will be way better than staring at radiated rabbits in the exterior-telescope all day. “Let’s get out of here.” said Mr. Greenwell. “That’s a good idea,” said the kitchen staff, “I’m about to do the same, myself. Feel free to help yourself to some food.” She handed him a couple of reusable plastic to-go containers. Mr. Greenwell turned and walked out of the kitchen, making to leave the cafeteria entirely. Alice, noticing he hadn’t grabbed any food, snatched one of the to-go containers from him. “So, you’re just going to allow us to have this conversation about how we secretly love Salisbury steak the whole way here, and then not even get any of it? What kind of bull shit is that Mr. G?” “Oh, sorry,” said Mr. Greenwell, glancing toward the hallway, which by this point had calmed substantially, “I had something else on my mind. Let’s scoop up some steak for the road. And watch the language; we’re in public!” “Way ahead of you!” said Alice, darting back over to the buffet and filling the to-go container with steak and biscuits. Their lunch collected, they returned to Mr. Greenwell’s room. . . . . . . Mr. Greenwell sat atop his stool at his small desk, his hand at his face—his thumb on his chin and his pointer finger curled around his nose—as was his habit when he was thinking hard about something. Alice, having already devoured her lunch, was now back to staring into the exterior-telescope. “Man!” she said, her eye still pressed to the scope, “I really wanted that ConnectFour game, you know? I was really looked forward to whipping your old ass!”

5

Alice heard nothing in response. Normally, she knew, a vulgar comment like that would have elicited from Mr. G at least a snicker. But there was nothing. She tore herself away from the telescope, looking over to Mr. Greenwell, who still sat soberly on his stool. “We might need to get out of here,” he said. “How in the hell could we possibly do that? And where would we even go?” “I don’t know, and… I don’t know…” “Isn’t there a big door? A big metal, twisty thing that opens into the outside?” “Yeah, there is. That’s past the administrative offices, though. I don’t see how we could get by there.” “We’ll sneak it! There are some advantages to being seen as a helpless little girl by everyone, you know. Maybe I can trick them; allow us some time to get by.” “And what would we do once we got outside?” “Huh?” Alice was momentarily confused. She scraped her foot across the collected dust of the floor before understanding, “Oh!” she said, “Because of the radiation!” “Yes,” said Mr. Greenwell. Alice hadn’t ever been out of the colony. Not really, at least—not since she was two years old, when her parents had dropped her off here. “Don’t they have suits?” she said. “They don’t give those to just anyone.” “Well, obviously we’re going to have to steal them. Sometimes thieving is necessary.” Mr. Greenwell looked to the floor, considering this wisdom given to him by a child. “Okay,” he said, “We can try it. But first, we have to…” The walls of Mr. Greenwell’s room abruptly split and cracked. The floor shook. Loud crashes and bangs were heard from neighboring rooms. Mr. Greenwell’s twinsized bet rattled around on the floor before being flung sideways halfway across the room. Alice covered herself with her arms to shield herself from the oncoming blow of the metal bed, but it didn’t quite make it to her.

6

“It’s happening,” said Mr. Greenwell, “It’s actually happening. I always knew it would, but I guess I became too complacent down here, all this time—during this monotonous decade.” Alice darted to the exterior-telescope, looking intently and then immediately pulling away in shock before diving back and peering again. After a time, she removed herself from the device: “Holy shit!” she said, “We have to get the hell out of here—like now!” “Why? What’s going on out there?” “Lights, flashes… Dead stuff. Snakes and scorpions. I didn’t see any rabbits—I hope they’re safe—but I did see lots of smoke and fire. The ground is destroyed. There are some sort of drones digging into the sand. The ground is cracked, as if the colony is being uprooted.” “That’s what’s happening,” said Mr. Greenwell. “What?” said Alice. “The colony is being uprooted.” “What? I wasn’t serious about that; I don’t think so, at least… How could that happen?” “That’s one of the alleged weapons our political leader’s enemy could use against us. We use it against them, too—supposedly—over in their colonies; over in Siberia; over in the caves of the Caucasus.” “We’re just sitting under a bunch of shifting sand! We’ll be easy to dig up, right?” “Probably. I guess it makes sense that the Mojave colonies were among the first hit—assuming we actually were among the first. We must have been… But we’ve been down here for so long...” “They’re going to dig us up?” “Yes.” Dueling buckets of a flying excavator—its metal arms attached to a drone hovering overhead—crashed into Mr. Greenwell’s ceiling, subsequently scooping out and gutting the majority of his room. One of the buckets nearly scooped up Alice, though she managed to spin out of the way unharmed.

7

“Holy shit!” she said, crawling backward away from the drone. Her back against the door, she twisted it open and fell backward into the hallway. Following her, Mr. Greenwell lifted her up. In the hallway they saw panic. No one knew what to do. Everyone was darting around like feeder minnows trapped in a fish tank as the net delivering their doom moved around the aquarium. “We have to get to the administrative offices!” said Alice, tugging at Mr. Greenwell’s red checkered button-up shirt to hurry him down the hallway, “We have to make it to the exit.” “Right,” said Mr. Greenwell, beginning to move down the hallway as quickly as was possible with his cane. Abruptly, the front end of a bulldozer drone pushed through what had previously been Mr. Greenwell’s doorway. The drone then hovered upward, among the furthering wreckage, and reached out its excavator arms as if to entrap Mr. Greenwell in a pincer. There was nothing he could do about it; he felt the pinch of the sharp metal as it broke the skin of his abdomen. Alice shrieked in startled terror. Mr. Greenwell looked at the drone, which as a result increased the pressure of the pinch. Mr. Greenwell wasn’t aware that drones had been made capable of sadism. “Go,” grunted Mr. Greenwell, “There’s nothing I can do; I’m toast. Get the hell out of here, kid.” Looking at Mr. Greenwell one last time, Alice then turned and scrambled down the busy, chaotic traffic of the hallway. Walls crumbled around her; stones from the wreckage fell from the ceiling like pieces in a Connect-Four game. Alice would be lucky to make it to the administrative offices alive, she was well aware of that. She pushed on, nonetheless.

8

The Serious Business of Childhood a conversation with Christine Ferrouge

Often times the art that changes us comes into our lives by happenstance. But I was lucky enough to have an artist fall into my life. I met Christine Ferrouge by chance, via email. She reached out about her upcoming show—Watching/Waiting (April 27 - May 27 at Oakland’s GearBox Gallery) and graciously offered for us to use the space for a reading. Allow me to digress: the Romans believed that genius was a wind that flowed through people. If you’ve ever sat down to create something you know that electricity. It’s part of the magic of being an artist. But there is also magic in finding people who see you, and you see them. I felt this way with Christine. Carlos and I visited her at the GearBox Galley, then took a detour to her studio to view more of her paintings. From the colors she used, the creaminess of the oil paint, to the nuanced explorations of girlhood, I was enamored. It felt like home. Ferrouge’s work and her studio buzzes with tactileness and motion—characteristics that were everpresent in my articulation of girlhood. Girls are fast. They are movers and shakers. I told Christine that I wanted this interview to be a collaboration. Even though I found kinship in her and her work, I wanted to dig deeper. I asked her: what question do you want to be asked? And five days later, at the interview, she answered: I want to be asked about my painting’s connection to art history and contemporary girlhood. So that’s where we’ll begin.

9

After the Night Out, oil on canvas, 96” x 120”, 2022| Christine Ferrouge 10

Christine Ferruouge: My work is deeply rooted in an understanding of art history. Early in school, I discovered the Ashcan Painters, and was inspired by their gritty portrayal of everyday life and I was excited about where American art first became relevant in Western

art history.

I loved the founder of the Ashcan School, Robert Henri

(pronounced: Hen-Rye), who often painted children. I also fell in love with the brushstrokes of Manet, who could create dynamic faces and forms with minimal smudges of paint! I was inspired! I continued to study by looking at the old masters (studying in Florence, Amsterdam, and Madrid). When my daughters were young, I began thinking about how girls are reflected in pop culture and compared that to history. Their contemporaries had a weird princesses conglomerate that I was skeptical about. When I was young I wanted to be Wonder Woman because she was powerful. And I also grew up with the JonBenét Ramsey story, so as a mother, the dolling-up of young girls struck me as very disturbing. I don’t know how we ended up with so many cheap polyester princess dresses in our house! I never bought them, but they were everywhere, so I began to paint about them. I realized I was not the first artist to paint princesses, so I looked to Las Meninas by Diego Velázquez, and other portrayals of real-life princesses.

Details of Las Meninas by Diego Velázquez

11

The painting is important for a lot of reasons: Velázquez—the painter, himself—is in the painting; kind of the first selfie of art history. The artist and the audience are both aware of one another and reflected in the painting. On top of that self-awareness—to this day, there are people standing in front of Las Meninas, in the Prado Museum, continuing to be the audience that Velázquez intended. And they’ve been doing so for almost four hundred years!

Living Room Princess. 60” x 72”oil on canvas, 2016 | Christine Ferrouge Photo by Francis Baker

In contemporary art history, Kehinde Wiley and Kerry James Marshall have always been heroes of mine—for their larger-than-life, dignified figures and art history references. Hung Lu is similarly inspiring to me. My life-size or larger scale is crucial to my work. I want there to be a physical reaction and presence to the characters A six foot man musts to look up at these little girls to witness them. 12

London Pinkney: I could sit in all this knowledge for hours. I love that we began like this. We have this knowledge, so now I want to ask: who are you? CF: That’s so existential! (laughs) I always say I am simultaneously a full time artist and full time mom. And my subjects are my girls and girlhood. So I am both raising them and studying them.

The Exchange, on oil canvas, 120”x 60”, 2023| Christine Ferrouge Photo by Francis Baker

LP: I have a kinship with you because, as a writer, I have an inverted experience—I study my mother as she is raising me and, somehow, also raising her inner child. How has your role as a mother influenced your art, and how has being an artist influenced how you parent? CF: A core part of who I am is being a reflective person, so, in reflecting on what I do as mom, I am shaping that role. And what I do as a mom, shapes the work. It goes around and around. The part that blew my mind when you asked that question is the fact that 13

my girls are also watching me. I realize that it is normal for me to watch them and they understand what the paintings are because that is their life—they know me and what is going on with that work. And they understand art. So they are my best audience, because they understand art history and who I am. It’s us knowing each other, which is incredibly intimate. As a figurative painter, I have always painted the people that I know, and now the people that I know the best are my three daughters. When I have concerns about them as humans moving through

contemporary culture or through girlhood, I use the

paintings to work through those feelings. Much of my work starts as a question. I worry about how they are influenced by their social culture, or how they will survive wildfires and invisible environmental toxins, but I explore it via art, and come out on the other side. In the work I climbed toward hope, and recognized how strong my daughters are, and how adaptable I think about the importance of imagination as play, and how it allows us to create different realities for ourselves that help us define who we are and give us skills to cope with life. So in my work, I’m starting with my girls, but it relates to every person who has ever been a child. LP: I find it interesting that paintings come out of anxiety, I would think with anxiety, you would want to move away from the stimuli rather than sit in it. Does art work as a coping mechanism of art that allows you to sit in anxiety, or have you always been the kind of person to do so? CF: Fear is bad. But in a way, I think a lot of good art starts with anxiety because art is a good way to process life. And more importantly, if there are no questions or something to solve, what is the point of making the art? I think there has to be an exploration. My process of painting helps me find answers and usually surprises me with deeper and more universal connections to others than I initially perceived. LP: How did your daughters become your subject matter? CF: I knew that I needed to be taking care of myself to be a good mom. And as mom, I didn’t have the freedom to go over to a friend’s house for five hours and have them sit for a portrait for me. So, I started painting the people around me, which were my 14

daughters. Painting my children itself is an act of rebellion, as many women have been criticized and questioned throughout art history—even by feminists—that they should not, or cannot possibly, be both a mother and artist. LP: You have described that your work is about “the serious business of childhood,” which I love. Children aren’t respected in American culture. They are seen as accessories. And girls are categorically not respected for the cultures they create for one another and amongst themselves. How has this artistic journey revealed new things to you about childhood, and more specifically, girlhood?

Picnic, oil on canvas, 60” x 72”, 2020 | Christine Ferrouge Photo by Francis Baker

15

CF: I love what you said about girls and how they create cultures for one another and amongst themselves! That is so important! Often when someone looks at one of my paintings, they relate to it in terms of their own childhood before they think of someone who is currently experiencing childhood. For many years, my daughters and I refer to the person in the painting as “she, her, or that person in that painting”—not actually my daughters’ names. We all understood their likeness was simply a character that could

represent anyone. I love the fiction

disclaimers at the beginning of novels! It’s so funny to me because it is impossible to not base your inspiration on real people! I haven’t thought of myself as any of the characters in my paintings until more recently, as my oldest daughter is looking more like a young woman than a child. Also I constantly try to peek into their brains and they are starting to think with more maturity about the world. When they were younger I was clearly the mom looking in at playtime. Even though I related, I didn’t feel like I was painting about myself. It is healthy to not see too much of yourself in your kids. They are separate people. LP: Do you feel like that healthy separation between these characters and you also mirror the distance a mom should have with her kids? CF: Yes, And I think it’s helpful. Being both an artist and a mom helps me create healthy boundaries. My children are not my subject to manipulate, and likewise my paintings are their own thing- their own beings. Much like with kids, I make them then they go off into the world. It’s a healthy artist philosophy—if you are overly precious about something- you ruin it. A good artist responds to the needs of the painting and isn’t overly controlling. Similarly, there are things I cannot control in my daughters lives. I do what I can, and then I watch and wait. LP: What I love about what you do is that your subject matter is living. Yes you are a mother who is an artist and those identities intersect, but to have subject matters that live with you and grow with you feels so ripe with potential. At least right now, the theme of your work is girlhood, but do you see that shifting as your daughters get older? Is womanhood going to be a new theme? Or, as odd as this sounds, are you going to find new children to paint? 16

CF: Who knows?! I don’t think I’m ever going to stop being fascinated by my girls. But when they grow up and move away, will I have to paint other people again? My girls’ friends and even a few strangers are subjects in some paintings already. Or maybe I’ll have to paint about myself. (Laugh) That sounds really funny to me. ...All I know is: you have to follow your interest to make good art. And right now my inspiration is my three daughters - and their internal and external worlds. LP: It feels like the second art project, is you as an artist chasing this subject matter. As if the art is also in making something perpetual. Perpetual girlhood is not a real thing, but it feels like your work captures that in a very noble way. CF: The things that make us who we are are always part of us- and we form those things during childhood—imagining, inventing, reflection. Those actions are always in us. In my new work I’m growing interested in how girls relate to one another—whether friends or siblings. I remember getting dressed up or ready to go out with girl friends- like for a birthday or a dance. It was a time when you proclaimed who you were to some kind of audience, and it was important. You were becoming. And there was a monumental feeling about it—that it should be documented. That sense of becoming doesn’t go away, no matter how old you get. Becoming is perpetual. When the girls and I did the photoshoot for the Picnic series, we went out into the desert and set up a picnic with pink-frosted cake and bright blue lemonade. Getting to the location was somewhat dangerous and together we had conceptualized the props and meanings of it all.

As we were acting out this strange tea party which I was

photographing to paint, I thought to myself, which part is the art? This event?—or the painting I will make in the studio? We are the art and the art is life. LP: I’m biased, but the artist life is healthy: you have to know your worth, act with intention, know how to create community, set boundaries.

17

CF: Absolutely. Being in a place where you’re creating is a healthy place to be. There is a universal desire to create, even if you are not in the creative fields—you might be building a company or building a building or building a family. But it’s all creating. LP: Tell me a little bit about the upcoming exhibit, Watching/Waiting. CF: The title of the show is about suspense, the sense that something may be about to happen. For me, it is what I do with my girls—I am constantly watching and waiting. My show partner, Joy Ray, makes sculptural weaving that look incredibly fragile. Joy and I found visual connection in the art of falling apart—my paintings kinda look like they’re falling apart, and Joy’s work looks similarly, but neither work actually reaches that place. She explained to me that her weavings are inspired by a memory of watching people walk on to a semi-frozen lake in Southern California. As the people walked across the lake, cracked and splintered beneath them, so her art captures that precariousness. It is about that tension. And I resonate with that because as a mother watching over my girls, I’m often aware of the ways they or the world around them could fall apart. That goes back to the watching and waiting—that’s all I can do as they move through girlhood. Watching/Waiting runs from April 27th to May 27th at the GearBox Gallery in Oakland!

Left: After the Night Out, oil on canvas, 60” x 72”, 2022 | Christine Ferrouge Photo Christine Ferrouge’s work by Francis Baker

18

Right: Apparition, plaster, cheese cloth, and thread, 10” x 12”, 2022 | Joy Ray Photo of Joy Ray’s work by Anna Pacheco

LP: Yes! Thank you so much for letting us host inside that space. And I’d love to end on some fun, light questions. Since I am a Parliament Funkledelic Fan, I must ask: are you a stoplight, a flashlight, or a neon light? CF: Ooh! I’m probably a neon light, but in my work I’m using a flashlight. I’m neon, I’m not someone who shies away from attention. I wear a lot of black, but I love color. LP: And that leads me to the next question: What is your favorite color to work with? CF: The moment I get to place red on my canvas is always a favorite moment. You have to use it sparingly, and it’s not my favorite color in general, but it brings me back to the pure love of paint. From my earliest memories. I remember dipping my paint brush in dripping red tempera paint at the preschool easels and making that mark on the paper. There’s nothing as exciting as that. Red is a power color—it’s fire, it’s blood, it’s excitement, it’s passion. And you have to use it decisively. LP: And the final question is: what’s next for you? CF: After I launch this show, I need to get back into the studio! I’m starting paintings about girls getting ready in mirrors, and about our relationships with one another and ourselves. I’m excited to be in my new LA studio as well, where I’ll be hosting studio visits and enjoying focused work time this summer. Being an artist is a continuous journey. Thank you so much for this interview. I cherish our conversations. It has been wonderful to work with you. We are thrilled to host The Ana at GearBox Gallery for your upcoming release party!

19

Three Masked Princesses, oil on canvas, 72” x 48”, 2015 | Christine Ferrouge Photo by Francis Baker

20

Watching/Waiting April 27 - May 27, 2023 GearBox Gallery in Oakland, CA

. . . . . .

To follow Christine Ferrouge: christineferrouge.com @christineferrouge

. . . . . .

Ferrouge’s recent honors include exhibiting in the deYoung Museum Open Exhibit and solo show at Gray Loft Gallery. In addition to studio practices in Oakland and Los Angeles, Ferrouge is a teacher, curator, and promoter of the arts, who contributes passionately to art communities such as: the Oakland Art Murmur, Los Angeles Art Association, and Kipaipai Fellows.

21

After the Costume Party, oil on canvas, 96” x 108”, 2015 | Christine Ferrouge Photo by Francis Baker

22

Deac poetry by

Elisha Taylor

I never hear her voice anymore in my name/I just hear the common tree planted firmly by living waters/Swaying my name from first to last and letting his leaves bristle Durrell in the middle/Just as calmly as he could seem/

23

in the poet’s house, i am the mirror nonfiction by

Erick Sáenz

24

“There is no problem of influence because everything writes even when I don’t write” - Lisa Robertson

26

Con mucho amor a Ángel, Farid, Tato, Vickie, & Roque - ese fin de semana y para siempre

27

// I believe in the power of books. They find you, if you weren’t aware, dear reader. When you’re at your local bookshop browsing dusty shelves for something to jump out at you—that’s the power of books. Other times, it’s a recommendation from a friend / partner / lover. The book connects y’all in a way that can’t be undone. It’s an anchor for a certain time and place in your life. And you can always go back; reflect remember. // In the Spring of 2018 I found myself returning to a nostalgic place. My first book had just been published by a press back east and I was invited to join five poets for a weekend of readings in Monterey. So I found myself traversing across those familiar farm landscapes of Central California on the way to the event. Imposter syndrome and that familiar nervous ache in my belly traveled along inside, like the words tattooed on my right arm; taking dreams back at one thousand miles1 down highway 101. // Have you ever noticed all of the different textures books hold? 1.

Grab a book off your shelf. Don’t think about which one, try to figure out which will be the most satisfying to touch. It’s better when it’s random.

2.

Hold the book between your thumb and index finger.

3.

Pause and think about how it feels on your finger tips. What is there and what isn’t?

4.

Take your middle finger and brush the book back & forth.

5.

Close your eyes.

6.

What do you feel?

1 “Forty Four Sunsets” - The Saddest Landscape

28

// Ángel and I met at a reading in Santa Cruz. By that time I had read (and re-read) his debut collection. My book had just been accepted by The OS and I was going through the motions of becoming a published poet and a deep-setting imposter syndrome like a shadow. Somehow I knew immediately Angel is from Los Angeles; I could feel the traffic, smell the heat radiate off concrete. We’re both adjacent to LA; close enough to know the city but far enough away from the congestion. the attitude, the speech. We know you gotta hit up the Tommy’s Burgers on Beverly for those late (late) night munchies; but beware the drunks,

and those chili cheese fries sitting in your belly for the rest of the

weekend.

// When I was in my late teens & early twenties I was obsessed with punk music. But more than that, I was obsessed with all the tiny micro-genres of the genre. I found myself devouring information about bands and labels. I’d spend countless hours reading liner notes, noting who played what, documenting labels to look up later, either in real life or on the web. Years later, I find this practice has stuffed my brain with mostly useless information. I see record covers in my mind. I can tell you what band(s) someone played in and how long they existed. Every few weeks I find myself doing a deep-dive on the internet, vastly expanded from those days, and nostalgically downloading obscure EPs long out-of-print. If this obsessive practice did anything for me, it taught me how to throw myself completely into something. To live and breathe this… something.

// When Ángel’s debut collection, Black Lavender Milk, came into my life; I was living in Monterey for the third time in 10 years. Let me pause for a second and explain: I earned my BA in English at CSU Monterey Bay, and then promptly moved back from Southern California to earn my Teaching Credential. After that I floated around California spending time in various cities but never feeling home. For me Monterey was (and frankly still is) a place of transition…I return

29

when I need a reset. This time around would turn out to be my last jaunt living in Monterey, although I still visit as frequently as possible. In the months leading up to my final move to Monterey, I had found my writer’s voice. I’d always had an interest in writing from a very young age, but I’d never made time to focus on my writing or develop a regular practice. Once back I suddenly felt compelled to write about the corridos that kept me up at night, the familiar smells of fresh pan dulce, riding my bicycle and breathing in that salty air, the wind howling in the early mornings, that fog settling on everything outside my window, obscuring the familiar and making things more familiar.

// In preparation for the gathering, I read the latest books by all of the poets whom I will soon be kin. We are strangers, but I feel connected to them through textures. They say the words I could never find in my throat. After the weekend I write a poem for each of them. I am too embarrassed to ever hit “send”

// Everything loops; a snake eating its tail. What’s that called again? I’m living in Southern California (again) and invited back to Monterey (again). This time as a guest poet for a Latinx Creative Writing class Ángel is teaching at the college. I’m nervous but quickly put at ease by the students’ enthusiasm for my book. Rather than go through the passages I had pre-marked in my own worn & creased copy, I let the students curate my reading. They excitedly shouting out the pages of their favorite poems. I comply, reading on a whim. Ángel and I laugh about this impromptu poem-on-demand over beers afterwards.

// 30

The last night of the Latinx Symposium feels like a baptism. The imposter syndrome is gone. I do not know if it will return once I’m back to my real life in Southern California. But I feel different. Later, we drink, we laugh about the weekend, we watch music videos, cry in each other’s arms. We scream at the ocean, the pitch black night. // My hands hold fire I better put it to use2

//

I find myself at the ocean. Every time I return like the punchline to a bad joke no one is telling. It’s because he is there; we ebb & flow through a conversation that is only for us. He was never great at listening, but now listens patiently at the voice that I found after he was long gone. I say all those unsaid things I couldn’t while I watched him dying. Maybe the point is he can’t really talk back. su voz como el viento llenando esos espacios vacios, tantos años después 2 “My hands hold fire” - Sinaloa (is a state)

31

// The same weekend I visit Angel’s class, I’m asked to give a writing workshop at the local Boys and Girls Club in a sleepy Monterey suburb. I stop at the ocean; for advice, or to calm my nerves. The pavement is wet from a recent downpour, that smell mixing with the Eucalyptus-lined pathway. I read some pages from the book and then tear out a page and film it saturated with saltwater, and then tumbling away with the waves. Not my last communication, but a good ending anyways. The workshop goes well; I break through with one kid in particular whose story is similar to mine. He knows paternal loss. We are kin. // We all hop into a rented van the second day, heading to Salinas. Where the first day felt … “academic,” this feels more ________. Farid and I stay together in one of the college apartments I know well. We drink until the wee hours of the AM, and the coffee feels good in my throat and stomach. Ángel is behind the wheel, looking the part of a tired parent taking their kids to a practice of some sort. The day consists of a writing workshop with youth from the area, and a reading that includes local poets. I am taking it all in. // Later, write poems for each of them. Too embarrassed to share; love letters from an imposter.

32

// In the poet’s house, i am the mirror. taking it all in: Tato reading their poems the 2nd day in Salinas - seated on the floor; confident, relaxed. Moderating a writing workshop with Roque - the young people sharing their stories while we listened, intently. Driving Farid to the tiny Monterey airport; early and hung over. Vicki reading her poems the 1st day in Monterey - the ease in which she spoke Spanish. Crying on the balcony with Ángel, darkness carrying it away. // Several years later I’m eating chicken wings and drinking beer with friends. It’s been a while, although we live in the same neighborhood, and it’s nice catching up. One of them says something like the art world tends to fetishize poetry. The line bores into my head for several days and then finally I remember why I agree with the statement. // The last excursion we take as a (what do you call a group a poets?) is to BAMPFA for a reading Ángel is asked to do. The crowd is very… white… for lack of a better word, a stark contrast to the people we’ve surrounded ourselves with all weekend. We get there early, and find ourselves in the awkward moments of milling around looking at the art and paying way too much for snacks. Finally they are ready to begin. Ángel absolutely kills it. Their mix of performance and poetry is something I am always envious of. I’ve been privy to many iterations but this one is probably my favorite. As they read to their ancestral peoples, a rope is woven in and out of the crowd. People seem embarrassed by the fact that the script has been flipped: they perform too. No safety in the spectator. 33

By the end everyone seems to have missed the point. They are unsure how to react once the performance is done, standing idle while Ángel collects their artifacts. The other reader reads and a sense of familiarity with the work (or the person) fills the room. A strange way to end. // Later, a cenote surrounding White-washed space bodies pose, then goodbyes. i think we stopped for burgers, one last night together. // We hug outside BAMPFA; damp Berkeley air. Two need to leave to catch flights, head back to their version of home. // I’ve sat down and tried to write about this countless times, words never quite right.

34

I think about the famous scene in Stephen King’s 1986 film Stand by Me.The main character finally is alone with his thoughts while his friends sleep nearby. He sits quietly and watches a deer approach and linger for that one extra second before vanishing back into the background. He returns to his friends but never tells them about what he witnessed. The memory his own. The point, I think, is that the main character has this great moment of clarity that he doesn’t need anyone else to justify. And maybe that’s why I’ve been reluctant to share. I keep these moments in my heart, return to them when I need to remember what it is to be a poet. I hope you find these moments, too. // Someone remembers to document the final moments of the weekend. We’re all there.

35

Words on Fire, Karen Gomez

36

On Turning 17 poetry by

Alexandria Wyckoff I have two rules on my birthday:

1.

2.

be grateful when they slice across my knee

smile when needles pierce my skin and flood my veins with drugs I try to convince myself: this is exactly what I wanted this year. Could I go back to the day I broke my future? Kick the ball away, this fragile

body, built haphazardly, waits for the perfect moment to fall apart like a Jenga tower teeters back and forth. Don’t lunge against the hardwood floor; that waxy surface, that squeak. My leg takes the momentum, collapses onto itself with a loud, final snap. There was a moment. I could have walked away.

37

The Condor’s Cove, Violet Bea 38

What Would Khadijah Do? fiction by

Akasha Neely Fuck six am. Kenya Jenkins plundered her one-bedroom apartment looking for a tiny Spider-man sneaker. Mornings were chaos because she had to take the bus to open at The Bizarre Burger Bazaar where she worked. She opened her refrigerator to grab an energy drink. What the fuck?” she mouthed. A tiny Spider-man sneaker rested on the bottom shelf of the refrigerator. She sighed in defeat, chuckled, and placed it next to its sister on the floor. Every morning, Kenya placed her daughter Serena’s outfit for the day in the ripped armchair next to the couch where Serena and her grandmother, Rashida Washington slept intertwined in a crochet of skinny limbs and blankets. Root and seed. They were so cute that Kenya almost forgot how much they both worked her last damn nerve somedays. Almost. Kenya placed her mother’s hypertension and heart disease pills in a cup on the coffee table. She set the third alarm on her mother’s cellphone for 7:30. She cleaned the kitchen and the bathroom knowing that it would look worse than Deus Falls after the first crack epidemic in the eighties by the time she got home. She kissed both of her leading ladies on the forehead and left. After twenty-seven cramped minutes on FTA #3 bus, she arrived at her job already tired and ready to go home. A black Suburban with tinted windows pulled up to the drive-thru window where Kenya was working. She gasped once the window rolled down and the plume of marijuana smoke cleared when Pete, someone she hadn’t seen or thought about in years gave her a twenty-dollar bill.

A Decade Earlier Fuck six a.m. Kenya Jenkins trudged to the bathroom. This was her second month attending Cardigan Hills high school way up on the northside with all the fancy people. She had gotten accepted into their program for gifted students and transferred

39

from Deus Falls high which was only a few miles from her home on the southside. She flicked a cockroach from the door and ducked as a bigger one went flying over her head. Inside the shower, the water hotter than the temperature of the surface of the sun, Kenya imagined winning past arguments and brainstormed story ideas. She had just started writing a comic book and novella series about Khadijah, a black superheroine, she would have nuance and not just be arm candy for a male superhero; or a reincarnation of the blaxploitation era. She thought of her backstory: Freshman girl bullied and beaten up gains super powers from drinking the sludgy brown water that flows from faucets in the ghetto. She would have super strength and the ability to set things on fire with her mind. Maybe a few lasers. Never-mind – no lasers. A keen understanding of the universal and intricate human narrative. Khadijah still needed flaws, though. In her imagination, she always had the perfect clapback, the perfect story, and the best character arcs; however, when it came time to put pen to paper, she found herself lacking. Her body seemed to be in want of the skills necessary to translate her Voynich manuscript of thoughts into pragmatic and understandable symbols. Kenya got dressed and upon exiting the bathroom collided with her mother who was entering the bathroom in her bathrobe. “Ouch,” Ms. Washington rubbed her forehead and blinked several times. “I always knew you was a hard-headed chile.” “I got a sneaking suspicion on where I got it from,” Kenya massaged her own throbbing forehead. “I’m working a double tonight, so I won’t be home when you get back,” Kenya’s mama reached into her pocket and pulled out a handful of loc jewelry. “Your locs are starting to mature,” draped the silver coils over the handful of Kenya’s locs that were separating; she was in the process of free-forming to connect with her ancestors. “There! Now you look like you’ve just hit a milestone on your journey.” Kenya left her apartment and she was almost to the bus stop when three young men approached her. Kenya’s pulse quickened; she didn’t want her body to be used as a masturbation toy. The weight of the straight razor she carried in her pocket made her feel more nervous than anything. Would she bitch up if accosted? Khadijah wouldn’t – she would just start slashing.

40

Khadijah would use her powers of pyrokinesis to burn anyone that dared to run afoul of her. However, she was no Khadijah, as evidenced by her knees quaking with every step that put her closer to the trio of boys, who were looking less like teens and more like hissing vipers. “You got some money?” The shortest one asked. “Hey,” an angry and familiar voice. “Get away from my cousin.” Kenya was surprised to see Derrick. They had grown up together because their mothers were best friends at one point. One day about four or five years ago the Jakes came and took Derrick away. Rumors circulated that he was out and different. She no longer saw the boyish joy of playing It or being able to jump Double Dutch better than most of the girls in their class in his eyes; instead, something primal. Calcified. In. Time. “I ain’t e’en know dat was you, D. No disrespect, my nigga,” said the short thug as the trio backed away from them. “Got that four and a baby for the low if ya tryna talk later, D?” Derrick ignored the Lilliputian street pharmacist and handed her a wad of money. “Don’t come back through here for a while cuz some shit bout to go down. These young niggas out here wildin’,” Derrick dumped some loud into a swisher and hastily rolled a blunt. “My squad been posted up in the cut for a minute. Just stay off the block for a while. Niggas wanna scream gang shit until it’s time to start wettin’ mothafuckas then they turn into conscientious objectors.” Derrick lit his blunt, “Wanna hit this gas?” “No,” Kenya thought her reply curt and added, “I gotta get to school.” He was making her nervous, and the toaster on his hip wasn’t helping. Had he used it before? She didn’t want to know. Kenya nodded and hurried to the bus stop a hundred dollars richer; she was torn between making a mental list of art supplies and being concerned about Derrick; he was not the same person anymore. She didn’t think Khadijah could save him. FTA #12 bus arrived five minutes late and just as crowded as usual. Scanning her fare card was challenging because the driver took off like a greyhound tweaking on Molly after snorting an eight ball. Pushing through the stinky 41

thicket of people standing and holding on to the straps that dangled like canvas vines from the ceiling, Kenya saw a gap between an older man and a girl with purple microbraids. Diamond had used her purse to save Kenya a seat. The bus was the only chance Kenya got to hear and speak AAVE without judgement until she got home. Cardigan Hills was a culture shock. On her first day at the new school, Kenya answered a question and this girl with freckles and yellow dolphin teeth felt compelled to inform Kenya that she hadn’t pronounced syrup correctly. Kenya stopped raising her hand after that. “Hey,” Kenya waved. “Hey,” Diamond looked up from the stack of papers in her lap. “I’m just studying for my audition tonight.” “Good luck, y’all could damn sure use the money,” Kenya watched three more girls from Deus Falls high school get on the bus. “Definitely. The doctor said she got gangrene,” Diamond flipped back through her papers to start over. Kenya nodded and squeezed Diamond’s forearm. The three girls made there way to where Kenya and Diamond were sitting. “Hey Kenya, girl, we was just talkin’ bout you,” Mary, her former classmate, said. Kenya raised her shoulders and sank in her seat. “Remember when Roselyn used to bully you and one day you slapped her, and she stomped you out in front of the whole class? You had footprints e’erwhurr,” Mary said apropos of nothing. Laughter. Kenya sank. “Mary, didn’t Roselyn stomp you out cuz of a boy that year, too?” Diamond snapped. A cacophony of laughter joined the staccato orchestra of squealing brakes and rattling metal. That would’ve been the perfect Khadijah clapback.

42

“Look, y’all need to stop bringing up shit from the past. I am delivert now. I am filled with the Spirit,” Mary said clasping her hands together and raising her eyebrows to the sky. “You’re filled with an ‘s’ word and it’s definitely not ‘spirit’,” Diamond looked up from her notes again. “I gotta call Roselyn, later; her little brother just got killed over there on Temperance. He got caught in the crossfire.” Quida said. “The two-year-old?” Kenya asked. Quida nodded, “Shit ain’t e’en make the news. Sad.” She exited the bus after it screeched to a halt. The rest of the girls trickled off at different stops. Kenya felt a deep anxiety about Derrick. Another one of her own lost. She saw it in his eyes today. They were supposed to be better than Deus Falls – not succumb to it. Assimilation. Kenya exited at the end of the line and took the train the rest of the way to Cardigan Hills high. In her math class, Pete Jones, a jewelry-clad, boy who wore his hair in a dark caesar with 360-degree waves, arrived late. “Nice of you to join us,” said Mr. Albertson. “My business meeting ran long,” Pete said to the laughter of everyone except for Mr. Albertson and Kenya (who was busy drawing cartoon characters). There was a folded-up piece of paper on his desk – he had failed another test. Pete’s mood went from impish to forlorn. “Damn, my mama gon’ cancel my credit card. My father gon’ take my game away,” Pete lamented. “I just got done with being on punishment, too.” He sucked his teeth. “You’re missing a linking verb,” said freckle-face girl. “Link deez nuts,” Pete said. Mr. Albertson finally managed to quiet the class down after Pete’s clapback. “Mr. Jones, I want you and Ms. Shanika? Keisha? Sharknado? Charmander?” he stared blankly for a moment while he tried to remember her name, 43

(Kenya’s face burned, and she wished that Khadijah would just set the rest of her on fire). “Ms. Jenkins to work together.” “Are you busy after school? Can you come over?” Pete asked. “My mama will be home. She’s taking a personal day.” Kenya wanted to say no; but, she remembered her mother was working a double and being home alone was a bad idea today. She subconsciously touched the pocket that contained her straight razor, “Okay, sounds good.” Kenya smiled awkwardly. Pete lived in a two-story house nestled in the heart of a gated community. “Y’all rich?” Kenya couldn’t believe how high the ceilings were. Mrs. Jones, Pete’s mom, snores reverberated from the couch. “Us? No, we’re, like, upper, middle, middle class. I hate it. I want to live somewhere real like you do in Pleasant Meadows.” “Why? Everyone where I’m at is tryna get here. I would love to have this.” “Wasn’t there a quadruple homicide there yesterday?” “Yeah, and a little boy got thrown from a window on the top floor – it didn’t make the news, though; stuff never makes the news.” “See, nothing like that ever happens here. I hate living here. We’re the only black family in this neighborhood so every time I walk outside I feel like I’ve got a million eyes on me. Shit, leave my black ass alone.” “The gaze is something that I don’t think any of us get used to. Besides, living in a shithole doesn’t make you any more black than living in a nice neighborhood with good schools,” Kenya sat down on their second couch (That Pete sure had some nerve to complain). “I know, but I feel like a pampered puppy. I wanna be a rottweiler,” Pete poorly imitated a dog growl. Kenya’s ire grew, “I have this friend named Derrick that I grew up with. I don’t recognize him anymore because the streets have taken him and substituted something sinister. 44

He’s adrift in an ocean of asphalt and guns and I don’t have a fucking life jacket. My friend Diamond’s mama got the sugah and she might lose her foot because she got frostbite on her toes waiting outside for the bus, so she could get to work last winter. If you wanna be real then use your privilege to help black kids that live on the south side in poverty. We don’t have a lot of opportunities.” “Yeah, my mom says niggas on the southside are too busy smoking blunts and having babies at sixteen to ever do anything with their lives. She says we should just wall up that part of the city with all them niggas in it. My dad actually grew up not too far from you, he says niggas are too lazy to pull themselves up from the gutter.” Kenya took a deep breath and let the avalanche of bullshit ride, “Are you ready?” Pete was difficult to tutor because of his short attention span. He seemed more interested in trying to talk to her about every other subject besides math (“Do you comb your hair?” “Is your grandmother thirty-five?”). They worked for over an hour, before Kenya decided it was safe to head back. “Leaving?” Pete’s mom asked (she had woken up fifteen minutes ago). “I gotta catch the train and the bus.” “I can’t believe your mother lets a tiny thing like you take public transportation alone. Some parents just don’t care,” she stood up, stared at Kenya’s hair for a second, put on her wig, and grabbed her car keys. “Where do you live?” “Pleasant Meadows Housing Projects on the southside.” “Oh well,” she took off her wig, sat down, and turned on the television. “I gotta get dinner started. Pete, walk her to the train-station.” Kenya and Pete walked down the road toward the train-station. Kenya was impressed with all the well-manicured lawns they were passing. Pretty grass. “That Mr. Albertson’s a trip, huh?” The awkward silence made Pete’s question reverberate. “I like him,” Kenya mumbled. “I guess he cool,” Pete backtracked. 45

A siren stopped them in their tracks as a police car pulled up behind them. Kenya’s heart did a barrel roll. “Do not fucking move. If you move I will fucking shoot you, I swear to god!” Two cops rushed them; strong hands put Kenya face down on the sidewalk next to the pretty grass. The officers handcuffed them, went through their pockets – Kenya’s straight razor was confiscated. “Where were you between ten and eleven?” they asked. “Fourth grade, nigga!” Kenya was unable to hold back her vitriol. She paid for it with a sharp kick to her ribs. Where was Khadijah when she needed her? “Keep your bitch in line,” one cop said. There was dull thud followed by a sharp yelp from Pete. “It’s not them.” As quickly as it happened, they were un-handcuffed, and the police sped off. Pete climbed shakily to his feet. “That was scary. I thought we were going to get arrested,” Pete said softly. Braille patches of gooseflesh had formed on his arms. “At least you landed in the grass,” Kenya touched her scraped knees. That night while Kenya and her mother searched for a show to watch on Netflix, Kenya was struck with a sudden urge to ask a question that had been bothering her for hours, “Mama, what class are we?” “Girl, we ain’t even in the building.” Kenya didn’t quite understand the answer, but her mother was often cryptic. She decided not to worry about it and contented herself with playing with one of Ms. Washington’s neatly manicured locs. Kenya worked with Pete almost daily that schoolyear and he managed to pass math – with a “C-.”

46

Present “‘Fourth grade, nigga!’” Pete exclaimed. Kenya giggled at Pete’s perfect imitation of the ghetto twang she had at fourteen. “Hey, at least you landed in the grass, okay?” “Rebecca, this is Kenya, Kenya, this is Rebecca.” He gestured to his frecklefaced passenger then back to Kenya. Kenya waved as she handed Pete the greasy brown paper bag. “What are you doing working here?” Pete asked. “I would have thought you would have ended up a doctor or something? Did you ever make that comic book?” “A doctor? me?” Kenya laughed. It was a nice fantasy, but her and her mother couldn’t even afford community college at the moment. “Khadijah was just a fantasy of mine. Can’t eat by telling stories all day. It would be nice, though.” “You were so smart, you definitely got me through algebra freshman year, Mr. Albertson was on that bullshit,” Pete laughed. “I liked him,” she shrugged. “I work here, and I work at the comic book store in the mall on Andre. I got a five-year-old to take care of.” “I was a Yeti,” Pete pointed at the ring on his finger from the prestigious college up north. “My parents weren’t too happy with me at first: I kept snorting coke, drinking, fucking bitches, and failing classes,” he paused for a second in thought, “usually in that order, too.” “They paid for you?” Kenya’s voice raised an octave; though, in retrospect, she wasn’t sure why this shocked her. “Yeah, the whole way, too bad I’m not using the degree.” “What’s the degree in?” “Criminal Justice.” “Oh, what do you do?” “I rap,” he gave her his phone. “Check out some of my freestyles. My rap name is Assault Peter.” “That’s… interesting,” Kenya said as she looked through his information page. “It says here you’re from Pleasant Meadows? You’re from Cardigan Hills.” 47

“I know, but, you know how it is, it’s just music at the end of the day. Besides, somebody’s gotta tell the story of the poor ghetto youth across the country and get rich off of it. Plus, I grew up in their world I know how to navigate it better than a kid from the ghetto would,” he pocketed his phone. “It was nice seeing you. Don’t forget to add me on Instagram!” He pulled off. Hell, what would Khadijah do? Kenya just shook her head, laughed to herself, and went to the next order.

48

February poetry by

Abigail Pak It’s February. I switch the phone to my other hand as I walk around my neighborhood, trying to convince a friend that I hadn’t thought about dying for a while, when I see the lizard laying on the sidewalk. It’s dead. I guess that’s important to know. With its soft belly and tucked in head, I can’t tell how it died except for a missing foot. And I’ve seen more gruesome things— a gutless bird, an eyeless calf, half of a runover pronghorn—but after my dog died two years ago, the ones that look like they’re sleeping haunt me the longest. The voice speaks in my ear about talking to someone as I bend down, setting the lizard into the wet grass with a half-broken twig. At some point, I think I stop listening, looking up to clouds the color of silverfish I find smashed in boxes after sitting in the garage over the summers, listening to waxwings fly by, noticing, for the first time, how cold my hands are. I forgive my hands for being hands. I walk back home and the couple next door with the poorly trained dog has just pulled into their driveway, unloading groceries. He weaves between them like a mosquito in June, with a tail as fluid as kite streamers, and not once do they notice how beautiful he moves.

49

I Love You Also, I Promise fiction by

Sophia Quinto Henry fell into the river and it was your fault. This is what I’m thinking about: Rain plink-plunking off the bicycle, on its side in the dirt. Water beading on the shiny red metal; drops swelling and slipping to the ground. The back tire rotating slowly in the wind, squeaking twice with every interval. Snails inching out from under rocks to soak the summer rain up into their fat, spongy bodies; they are replenished by the same water that killed Henry. The snails are puzzled by the bicycle, a new landmark in their habitat. But, as with sprouting bushes and resurfaced stones, they will grow used to it and trace paths into the dirt around it. Vines will weave through its spokes until the tire can’t turn. Furry animals will gnaw at the seat until the polyester stuffing spills out and dissolves into the earth like it belongs there. The bike will become a part of the forest. It will exist for the trees and the dirt and the snails, not for Henry, because Henry threw it to the ground and raced to the riverbank, chasing you, and fell in. Sometimes I wish it was you who died. I will never tell you that; it’s a wicked, twisted thought. But. You are just a boy. Nine years old. You have pink cheeks and skinned knees. When you laugh, flowers bloom and the sun brightens and I wonder how anything on Earth could be so beautiful. You play in the forest with imaginary pirates and ghosts and dragons, you chase your friends through the trees shouting I’m gonna get you I’m gonna get you! until you all collapse in a giggly dogpile. You need your dolphin-shaped night light and your stuffed calico cat Albie smushed under your chin to fall asleep. You are loud and sweet and funny and alive. 50

But if it had been you and not your brother, I wouldn’t blame the son I had left. I would look at him and think Oh, my poor darling who has lost his big brother. I look at you and I am horrified. I look at you and I think I hate you I hate you I hate you I wish it was you and then I pinch the skin on the back of my hand hard because a mother isn’t supposed to think like that. But I do. I do, in the dead of night, when you and the animals and God are asleep and I can’t swat the thoughts away with something to do. I lie there and I hate you and I hate that I do. I love you also, I promise. “Mom, I saw Henry!” you say. I scream at you. I cry. I threaten to throw my beer bottle at your head for making such a sick, disgusting joke. You don’t move. You’re standing in the doorway, gasping for breath, clutching the doorframe like it’s the only thing keeping you standing. “I saw Henry,” you say. “I really did.” You are not sorry enough. You tell me you are. You cry at night and whisper that you are sorry so very sorry. You tell me you wish you hadn’t been so selfish, so careless. But I see you walking home from school with your friends, smiling and shoving and shouting, and I wonder why you get to feel any happiness at all. I see you giggling at cartoons on Saturday mornings and I wonder how you can find anything funny in a world where Henry is dead. I see you bike away from our house, and I know you are heading for the creek that stems from the river because you come back with stringy, wet hair and a sunburnt face. I wonder how you could go near the river again when you know that its water filled your brother’s tiny lungs. But I guess I’m glad you’re having such a fun summer. When you lead me down to the river, we don’t pass the bicycle. You’ve made a new trail in the six months since then. You’ve hacked away branches and shrubs, tied purple ribbons around specific trees so you don’t get lost, shuffled your shoes over rough patches and brushed away pine needles to make a path. 51

Does it make you feel better, I wonder, to follow a different trail to the river than the one your brother followed to his death? Something is wrong with you, I think as I watch the back of your head bobbing in front of me. Your friends have a sick sense of humor and wanted to see your crazy, shut-in mother in daylight. Your brain can’t process his death, so it made you think you saw your brother in the shadows. Something. Something is wrong with you. But, for some reason, I can’t help but follow. When we get there, the riverbank is empty. You splutter and look around, peeking behind trees and squinting your eyes, searching the far shore. I feel sick for you. Your naiveté disgusts me. I want to grab you by the collar of your shirt and shake you until I can see in your eyes that you understand: your brother is gone. But I don’t do that. Instead, I watch you suffer inside your little-boy-mind that can’t make sense of the truth. I watch the grief seep into you again when you realize that Henry is not a ghost, that he was not on the other side of the river, that you are stupid. You are so fucking stupid. I tell you this, and you stare at me with wide eyes, mouth gaping. Your dad doesn’t call me anymore, and that’s your fault, too. He blames me for what you did. When I told him what happened, he cried and cried like someone he loved died, even though he hadn’t seen Henry since he was a baby. Henry was not his son, he was mine. Mine only. But you belong to both of us, and I hate that part of you that’s his. You even look more like him than Henry did, with your big, triangular eyebrows. Sometimes I can see your father’s face in yours, especially when you’re mad at me. You still call him. I know you do. Your voice sounds different when you’re on the phone with your dad than when you’re talking to anyone else. More desperate, more polite. You want him to like you so badly, to come back for you and whisk you away from your sad, mean mother and your quiet, empty house.

53

But I know him better than you do. He won’t come back for you, no matter how polite you are or how much you complain about me. Because he is awful and because you killed Henry. How could he love you after something like that? You and I don’t talk anymore, either. You avoid the house all day. I sit on the recliner, sleeping or staring at the TV, only seeing the face of my Henry in every sweet-faced child in every back-to-school-season commercial. Every night, you come home late and tell me that you were with your friends and you had a good time. I say, “That’s nice; there’s bread and peanut butter in the pantry.” I don’t ask why you look as bad as you do, and you probably do the same for me. Your cheeks become gaunt and your eyes vacant, and still I don’t ask. Sometimes it feels like it was both of you who died. August 4th. Five weeks since you first thought you saw the ghost of your brother. Five weeks since I told you you were stupid and watched your face crumple. This is when it happens. You have been going to the river, but your friends have not. You have been lying to me. I finally left the house this morning to get groceries. I couldn’t force myself to eat what was left in the pantry: canned beets, stale bread that thunked when tapped against the counter, and one rotting sweet potato. So I tied my greasy hair into a knot, threw a sweatshirt over my Doritos-stained T shirt, and stepped outside. The sunlight stung deep into my eyes for the first time in weeks, and it felt good, in a nostalgic sort of way. My bones were heavy and my shoulders ached, but now I had all the air in the world to stretch into. I reached my fingertips towards the sky like a child and marveled at how close to the clouds they could get if I just tried. But most of all: the smell of pine trees. I’ve missed the smell of pine trees. It was wonderful to get out of the house. To run errands like a person with nothing more important to worry about, to wander the familiar aisles and remember a time when it was all so easy. I didn’t think about Henry. I thought only about what food we needed and which brands were cheapest and which damn aisle would rice cakes be in because they’re not a cracker and they’re not a chip. 54

It was wonderful until I saw your friend Taylor’s mom. She waved me down, and I put on my best smile and let her hug me. She offered me her condolences and said she missed seeing me at Little League games. I wanted to change the subject, so I glanced in her Cheez-it-and-Oreo-filled cart and I said, “Picking up snacks for our hungry boys?” Her eyebrows scrunched upwards and toward each other, like caterpillars kissing, and she told me that she hasn’t seen you since the end of June. “June?” I said. “What do you mean you haven’t seen him since June?” And she said, “Only the Martin boys have been coming over. I figured you both were taking some time for yourselves.” I couldn’t look at her ugly caterpillar eyebrows anymore, so I said, “Oh, yes, right, we are. Just said that out of habit, I guess. Well, it was great to see you, great catching up. Tell Taylor we said hi, would you?” and then I walked away. I’m home now. I shove a new bag of Doritos behind a box of raisin bran so you won’t find it, and I don’t tell you what Taylor’s mom told me. You have been lying to me. The last time you lied was when you told me you saw Henry at the river, and I think back to that now. The foggy, glazed look in your eyes. The low, flat tone of your voice. Have you been like that since that day? Longer? I don’t know. I don’t know anything anymore, but I’m going to find out. The next day, after you leave, I follow your new path to the river. I run, and the insides of my sweatshirt sleeves bead with sweat. I slow only when I see you, crouching on the bank, right at the end of your trail. You’re laughing at something, the kind of laugh that suggests you’re with someone and you’re only laughing because the other person is. I press myself against a tree and crane my neck. Henry. Oh God, Henry. My tongue goes dry, pastes itself to the roof of my mouth. My knees lock, imprison me where I stand. My eyes blink blink blink but they cannot blink away Henry, sitting next to you on the riverbank, swinging his legs over the water. He’s wearing the 55

clothes he was wearing that day: a Fair Isle knit sweater, your old jeans, and his bumblebee rain boots with smiling bumblebee faces on the toes. It wasn’t even raining that day; he just loved those boots so much. Henry doesn’t look like himself. His skin is a sickly shade of green, his lips a purplish-blue. Dark patches underline his eyes, pinkish-gray foam borders his mouth and leaks from his nose. His eyes are clouded with fog, and I can’t make out the rich green behind it. His hair is soaking wet, plastered to his forehead like he’s just gone swimming. Like he’s come from the water. But still, it is him. It is inexplicably, undeniably him. The ghost of my beautiful, darling Henry in his bumblebee rain boots. He looks to his left, past your head, right at me, and smiles. Mommy. He’s too far away for me to hear his low whisper, but, somehow, I do. His voice is carried to me on the breeze; it threads through my ears like a needle through a button hole, it lays siege to my brain and it is all I can hear. Mommy, you’re here! How sweet he sounds. Mommy, you found me! How excited he is. Mommy, come join me! He turns to face the water. He jumps in. I run to the shore so fast that I skid on the gravelly dirt and have to grab onto you so I don’t fall. “What are you doing?” I yell, my nails digging into your shoulder. You don’t look surprised to see me. You don’t make a move to save your brother. You point a steadfast finger toward the churning water, where Henry’s hair is waving in the current. His face is upturned, and he smiles at me again, his lips peeling back to reveal that all of his teeth are rimmed by black. His shiny little baby teeth, rotting. His sparkly green eyes, dimmed. I turn away; I can’t look at him like this. But his voice. His voice, in my head, in every part of me, sounds exactly the same. Don’t worry, Mommy! It won’t hurt me. I’m part of the water. 56