7 minute read

ARTIST PROFILE

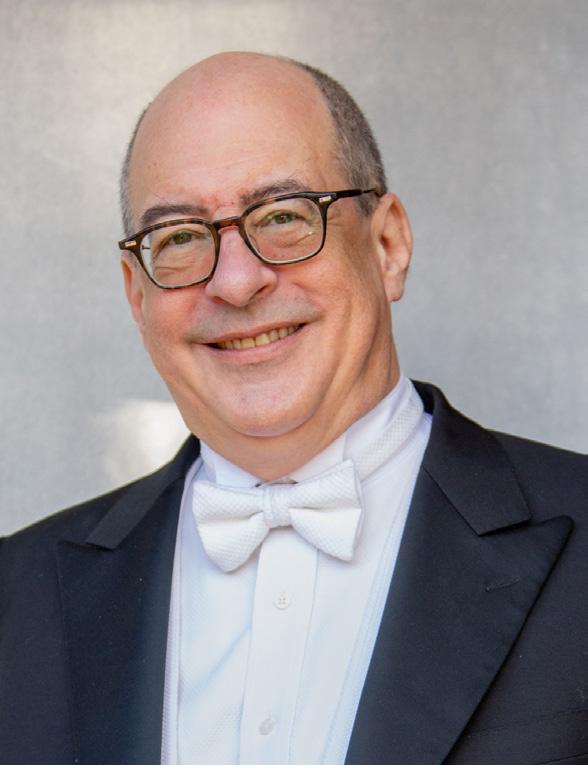

Gil Shaham is one of the foremost violinists of our time: his flawless technique combined with his inimitable warmth and generosity of spirit has solidified his renown as an American master. He is sought after throughout the world for concerto appearances with leading orchestras and conductors, and regularly gives recitals and appears with ensembles on the world’s great concert stages and at the most prestigious festivals.

Highlights of recent years include a recording and performances of J.S. Bach’s complete sonatas and partitas for solo violin and recitals with his long time duo partner pianist, Akira Eguchi. He regularly appears with the Berlin Philharmonic, Boston, Chicago, and San Francisco Symphonies, the Israel Philharmonic, Los Angeles Philharmonic, New York Philharmonic, Orchestre de Paris, and in multi-year residencies with the Orchestras of Montreal, Stuttgart and Singapore.

Mr. Shaham has more than two dozen concerto and solo CDs to his name, earning multiple Grammys, a Grand Prix du Disque, Diapason d’Or, and Gramophone Editor’s

Choice. His most recent recording in the series 1930s Violin Concertos Vol. 2 was nominated for a Grammy Award. His latest recording of Beethoven and Brahms Concertos with The Knights was released in 2021.

Mr. Shaham was awarded an Avery Fisher Career Grant in 1990, and in 2008, received the coveted Avery Fisher Prize. In 2012, he was named “Instrumentalist of the Year” by Musical America. He plays the 1699 “Countess Polignac” Stradivarius, and lives in New York City with his wife, violinist Adele Anthony, and their three children.

PROGRAM NOTES : PYOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY

VIOLIN CONCERTO in D MAJOR, Op. 35

I. Allegro moderato

II. Canzonetta: Andante

III. Finale: Allegro vivacissimo

DURATION: About 35 minutes

PREMIERED: Vienna, 1881

INSTRUMENTATION: Two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, four French horns, two trumpets, timpani, strings, and solo violin.

“Today I finished the concerto. It still has to be copied out and played through a few times... and then orchestrated. I shall start the copying out and add the finishing touches. ...

“Coming from such an authority, [this rejection] had the effect of casting this unfortunate child of my imagination into the limbo of the hopelessly forgotten.”

— Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (Born 1840, Russia; died 1893)

CONCERTO: A composition that features one or more “solo” instruments with orchestral accompaniment. The form of the concerto has developed and evolved over the course of music history.

CADENZA: A virtuoso passage in a concerto movement or aria, typically near the end and often played without strict adherence to meter or time. Sometimes a soloist writes his/her own cadenza, sometimes they are provided by the composer.

by Jeremy Reynolds

Whoever heard of a “Dear John” letter to a piece of music? When Tchaikovsky completed his first and only violin concerto with the help of a former student — possibly a lover — he proudly presented the work to its dedicatee, the virtuoso Leopold Auer, in hopes of a dazzling premiere. Instead, he received a gut punch. “Warmly as I had championed the symphonic works of the young composer (who was at that time not universally recognized), I could not feel the same enthusiasm for the Violin Concerto, with the exception of the first movement; still less could I place it on the same level as his purely orchestral compositions,” Auer recalled, 30 years after being shown the new work. “I am still of the same opinion.”

The pair made up years later, but the damage was done. Another violinist, a capable player but one who lacked Auer’s star power, gave the premiere, which turned out to be a disaster. After that concert in Vienna, influential critic Eduard Hanslick wrote: “The Russian composer Tchaikovsky is surely no ordinary talent, but rather, an inflated one, obsessed with posturing as a man of genius, lacking discrimination and taste... Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto, for the first time, confronts us with the hideous idea that there may be compositions whose stink one can hear.”

Ouch. Nevertheless. A few years after its premiere, the concerto caught the ear of another soloist, Czech violinist Karel Halíř, who championed the work in concert halls. It came to find great public enthusiasm, and today, the Violin Concerto is one of the most-played concertos in the repertoire.

Hearing it now, it’s difficult to imagine how it could have been so maligned initially. After a

FURTHER LISTENING:

Tchaikovsky: Piano Concerto in B-flat Minor

Symphony No. 4 in F Minor

Souvenir d’un lieu cher sparse opening tune in the strings, a thrumming accompaniment propels the music to a first — controlled — explosion of color in the orchestra. It settles quickly, and the soloist enters with a luxurious mini cadenza before playing the work’s

Continued on Page 16

PROGRAM NOTES : GUSTAV MAHLER

SYMPHONY No. 1 in D MAJOR

I. Langsam. Schleppend; Immer sehr gemächlich

II. Kräftig bewegt, doch nicht zu schnell

III. Feierlich und gemessen, ohne zu schleppen

IV. Stürmisch bewegt

DURATION: About 55 minutes

PREMIERED: Budapest, 1889

INSTRUMENTATION: Four flutes and three piccolos, four oboes and English horn, four clarinets, two E-flat clarinets and bass clarinet, three bassoons and contrabassoon, seven horns, five trumpets, four trombones and bass tuba, timpani, bass drum, cymbals, triangle, tam-tam, harp, and strings

“It’s the most spontaneous and daringly composed of my works. Naively, I imagined that it would have immediate appeal. How great was my surprise and disappointment when it turned out quite differently.”

— Gustav Mahler (Born 1860, Bohemia (present day Czech Republic); died 1911)

SYMPHONY: An elaborate orchestral composition typically broken into contrasting movements, at least one of which is in sonata form.

FURTHER LISTENING:

Mahler: Symphony No. 2 in C minor, “Resurrection Symphony” Symphony No. 3 in D minor

by Jeremy Reynolds

The double bass is the largest and lowest of the bowed string instruments in an orchestra. Eight or more basses in unison in an ensemble, along with the tuba, contrabassoon and bass trombone, give an orchestra that gravelly, tectonic depth of sound many composers wielded with aplomb in the 19th century. There are few solos for the instrument, as lower pitches don’t carry easily over the orchestra. Therefore the texture of the music must be utterly transparent, making the double bass solo in Mahler’s first symphony particularly significant and special for the instrument. This solo always earns a bow from the principal bassist at the conclusion of the work.

That solo is a tune most will be familiar with: it’s the French round “Frére Jacques,” but with a traditional Austrian twist in that it’s in a minor key, turning the normally cheery song into a funereal march. But let’s back up — critics and Viennese audiences hated Mahler’s first symphony, yet another example of a classical work meeting opposition before finding a triumphant place in the canon. Mahler, born to humble Bohemian Austrian and Jewish parents, first experienced music in the form of street songs and dances. He embarked on his first symphony in his late 20s, though he would revise the work numerous times throughout the course of his life.

The symphony begins (“Langsam, schleppend” means “slowly, dragging”) with a shimmering, ambiguous color, the note “A” spaced across many octaves of the orchestra, pregnant with harmonic possibilities. Unhurried, high winds enter with a mysterious, descending tune (highly difficult to tune in the piccolo). Soon, clarinets bounce in from the mist playfully, and oboes keen — this opening section takes its time, and about four minutes in, the pace accelerates, snatches of the earlier tune popping around the winds, while the orchestra plays a tune that sounds like a pleasant walk through pastures.

Continued on Page 16

Tchaikovsky, continued from Page 14 famous, tender main tune. Throughout the movement, Tchaikovsky recasts this melody for soloist and ensemble, at one point as a grand theme for the entire orchestra, with brass providing a thrilling rhythmic drive. The composer himself also wrote the demanding cadenza, which explores some of the highest notes in the stratosphere of the violin’s range. It ends on a trill, and the flute joins to play the theme once more, ushering in the final section.

Tchaikovsky cast aside his original second movement after the concerto’s first runthrough, realizing that it didn’t fit the rest of the work. (It can still be heard as the first movement of his Souvenir d’un lieu cher for violin and piano.) Instead, he wrote a Canzonetta, or “little song,” quite a lyrical

Mahler, continued from Page 15

The second movement — “Kräftig bewegt, doch nicht zu schnell,” or “moving vigorously, but not too fast” — is a ferocious peasant dance, an Austrian ländler, with the whole orchestra stomping mightily to introduce a daintier melody in the winds. The middle section is more genteel and plaintive. Then, the aforementioned bass solo kicks off the slow third movement, plodding along with almost sarcastic glumness before a pair of snide oboes rudely interrupts and changes the mood entirely. Then, everyone’s favorite tipsy aunt crashes the party, the E-flat clarinet leaps in with a snappy klezmer tune. The rest gem. For all its beauty, it achieves a mild sense of unease, a cloud over an otherwise sunny memory.

Strings introduce the racing finale without pause, mirroring the first movement and building up to the soloist’s first entrance. After a mini-cadenza, pregnant with tension, it’s off to the races, with the violin zipping manically in a thrilling demonstration of virtuosity and enthusiasm. Auer never recanted his early dismissal of the concerto, but even he grudgingly nodded to the work’s success later in life: “The concerto has made its way in the world, and after all, that is the most important thing. It is impossible to please everybody.” of the movement is a blend of these three elements and melodies. It’s this movement in particular that upset critics so deeply.

Mahler himself called the finale a “bolt of lightning, ripping from a black cloud,” an evocative epitaph. After a stormy introduction, brass and strings crash along with a savage melody. But slowly, deftly, the music transforms back to the pastoral calm of the opening, only to build to a stunning, optimistic A Major close.

Robert Spano, Music Director

March 24-26, 2023

Bass Performance Hall

Roberto Abbado, Conductor

Jake Fridkis, Flute

R. SCHUMANN Symphony No. 4 in D minor, Opus 120

I. Ziemlich langsam; Lebhaft

II. Romanze: Ziemlich langsam

III. Scherzo: Lebhaft

IV. Langsam; Lebhaft

Intermission

REINECKE Flute Concerto in D Major, Op. 283

I. Allegro molto moderato

II. Lento e mesto

III. Moderato - In tempo animato

- Tempo I - Più mosso –

Ancora più mosso

Jake Fridkis, Flute

LISZT Les Préludes

Video or audio recording of this performance is strictly prohibited. Patrons arriving late will be seated during the first convenient pause. Program and artists are subject to change.