5 minute read

PROGRAM NOTES : CARL REINECKE

FLUTE CONCERTO in D MAJOR, Op. 283

I. Allegro molto moderato

II. Lento e mesto

III. Moderato – In tempo animato –Tempo I – Più mosso – Ancora più mosso

DURATION: About 20 minutes

PREMIERED: Leipzig, 1909

INSTRUMENTATION: Two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, timpani, percussion, strings, and solo flute

“When I appeared the second time, fully prepared to hear a crushing verdict upon my work, [Mendelssohn] received me so warmly that I felt at once at ease. He astonished me greatly by playing several passages from my quartet which had particularly pleased him; as well as others with which he found fault...”

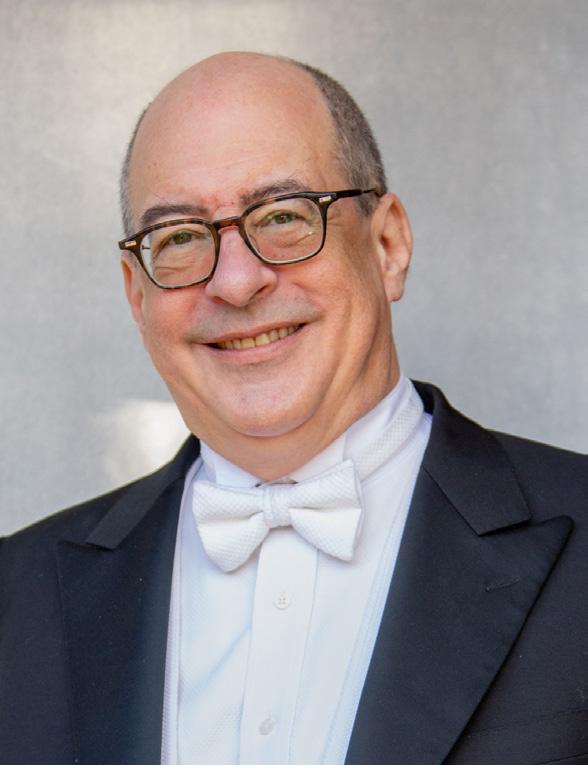

by Jeremy Reynolds

Reinecke’s life was remarkably unremarkable for a Romantic-era composer. Born in Hamburg, he received his musical instruction from his father and, displaying voracious talent, began playing public concerts at the age of 12. What a slacker. He found gainful employment all his life at musical establishments like the Leipzig Conservatory and the Gewandhaus Orchestra and as a teacher himself. The public received his music favorably, and he lived to the ripe old age of 85.

CONCERTO: A composition that features one or more “solo” instruments with orchestral accompaniment. The form of the concerto has developed and evolved over the course of music history.

FURTHER LISTENING:

Reinecke: Sonata for flute (Sonata Undine), Op. 167

Ballade for flute and orchestra in D minor, Op. 288 Octet for winds in B-flat, Op. 216

And yet, like Felix Mendelssohn, Reinecke’s friend and mentor, his music fell out of fashion almost immediately after his death. In Mendelssohn’s case, there’s credible scholarship to suggest that Richard Wagner smeared his reputation and contributed to a certain snobbery about Mendelssohn’s lighter blend of classical and romantic elements. Perhaps the association tainted Reinecke’s reputation as well? The New York Times critic John Rockwell snapped at his final major work, the Flute Concerto in D Major, “Reinecke’s sensibility was shaped by another Leipziger, Mendelssohn, and his flute concerto seems blissfully dated for a work composed in this century. It has an undeniable craft, and the final movement especially provides virtuosic moments for the soloist. But it is no masterwork.”

Harsh and undeserved. The concerto begins with a lush bed of sound in the orchestra, with winds pumping light and life into the introduction before the flute enters briefly with a single phrase, a smiling comment, before strings begin to swirl and carry the piece forward, like a gently flowing brook or stream. Soon, the flute enters once more, joining the orchestra in an increasingly virtuosic dialogue. Other flute concertos fall prey at times to banal, showy pyrotechnics that become unimpressive after a time. Reinecke remains focused on melody and substance. Truly a lovely tune and movement.

The second movement kicks off with plucked strings and brass. It’s foreboding, morose even,

Continued on Page 23

PROGRAM NOTES : FRANZ LISZT

LES PRÉLUDES (SYMPHONIC POEM No. 3)

DURATION: About 15 minutes

PREMIERED: Weimar, 1854

INSTRUMENTATION: Three flutes (third doubling on piccolo), two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones and tuba, timpani, snare drum, bass drum, cymbals, harp, and strings

“The character of instrumental music... lets the emotions radiate and shine in their own character without presuming to display them as real or imaginary representations.”

— Franz Liszt (Born 1811, Hungary; died 1886)

SYMPHONIC POEM: A piece of orchestral music, typically one movement, based on an idea or story. Liszt’s symphonic poems helped establish the genre of orchestral program music.

FURTHER LISTENING:

Liszt: Les quatre élémens (The Four Elements), S.80

Tasso: Lamento e Trionfo (Symphonic Poem No. 2) Orpheus (Symphonic Poem No. 4)

by Jeremy Reynolds

A pair of plucked pizzicato notes in the strings open Liszt’s Les Préludes, or “The Beginnings.” Low strings then embark on a melody that winds its way up into a higher register and blends into a wind chorale. Then the pizzicatos return, but higher, ditto the string melody and wind chorale. The music begins a build, fragmenting the earlier melody and inserting brass, sweeping along until at last, brass blazes out with a melody, as strings provide momentum with detached broken chords.

This work doesn’t have an exact “program,” meaning it’s not illustrating a specific storyline. During Liszt’s lifetime, there were several compositional camps that diverged along the lines of progressive tonality and whether composers should strive for “pure” abstract music or express ideas or stories through sound. Liszt, along with Wagner, was in the latter camp — he embarked on Les Préludes, intending it to be an introductory overture for a chorale song cycle about the four elements, earth, air, water and fire, though he later abandoned this plan. Instead, Liszt added his own program note, adapted from French poet Alphonse de Lamartine’s ode, also titled “Les Préludes”:

What else is life but a series of preludes to that unknown song, the first and solemn note of which is sounded by Death? Love is the enchanted dawn of all life; but what fate is there whose first delights of happiness are not interrupted by some storm, whose fine illusions are not dissipated by some mortal blast, consuming its altar as though by a stroke of lightning? And what cruelly wounded soul, when the storms are over, does not seek solace in the calm serenity of rural life? Nevertheless, man does not resign himself for long to the enjoyment of that beneficent warmth which he first enjoyed in Nature’s bosom. So when the trumpet sounds the alarm and calls him to arms, no matter what struggle calls him to its ranks, he may recover in battle the full consciousness of himself and the entire possession of his powers.

Continued on Page 23

Schumann, continued from Page 20

Next, a slower, almost funereal tune opens the second movement, with Schumann’s warmth still pervading the movement. Then, the scherzo, a stern, quick-stomping affair with a smooth, winding middle section. The finale begins, like the first movement, with winding, questing figures in the strings building to a quicker, sharper tune that carries the music to a shockingly positive conclusion.

The initial premiere of this symphony didn’t capture the public’s imagination

Reinecke, continued from Page 21 before the flute sings out a lament, high above the orchestra. And then, the finale — like Mendelssohn’s violin concerto, it begins with mock-seriousness, with a comically furrowed brow, before the flute enters to chirp and soar with a cheery rondo tune, reminiscent of the opening movement.

Liszt, continued from Page 22

And yet, Liszt actually added this program when the work was already near completion. This doesn’t detract from its validity as a program, but it is curious to note that the composer didn’t actually begin with this in mind. This suggests a malleability to any “meaning” to this sort of abstract music and is a useful reminder that even a composer’s intent can change. Beauty and meaning are in the ear of the beholder.

Liszt, though a prolific composer, was perhaps best known as a pianist to the same degree as the first symphony: “The Second Symphony did not have the same great acclaim as the First,” Schumann later wrote. “I know it stands in no way behind the First, and sooner or later it will make it on its own.” In 1851, ten years after its premiere, he revised the symphony, thickening the orchestral textures and linking the movements together. Schumann’s inner circle disagreed on which is the “better” version, with Brahms preferring the former and Clara the latter. during his lifetime. His concert tours are the stuff of legend, helped by a carefully cultivated, artistically dashing appearance that caused many 19th century women to swoon, much to the consternation of their husbands and fathers. While composers and virtuosos primarily served the aristocratic class during this period, Liszt managed to find more popular appeal through his particular style of playing and composition, a champion of the people who donated much of his concert proceeds to charity.

Though Reinecke’s music is rarely played today — for better or for worse is in the ear of the beholder — his list of pupils is a star-studded “who’s-who” of the classical repertoire and includes Edvard Grieg, Max Bruch, August Max Fiedler and others.

The Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra dedicates

The March 3-5 performances to Mrs. Rosalyn G. Rosenthal

The March 10-12 performances to William S. Scott Foundation

The March 24-26 performances to Teresa and Luther King

Generous Supporter of the 22/23 Symphonic Season