HealthPlus

WE DON’T HAVE TO KEEP DYING IN CHILDBIRTH

Black women are empowering themselves with knowledge, birthing plans, doulas and midwives

Black women are empowering themselves with knowledge, birthing plans, doulas and midwives

As we head into the fall season with moderate temperatures, warm colors, football and Halloween, we want to make sure the transition back into a “new normal” is as peaceful as possible. While many of us imagined our troubles would go away once “outside opened up again,” we are learning not only do we have to remain vigilant against COVID-19, we also must continue to remain healthy and happy as we navigate this precarious terrain. For many, returning to work has caused anxiety over traffic, wardrobe decisions and having to be around people who may or may not share your worldview or value your contributions.

That morning latte you have come to love in the safety of your home while working remotely may now come with a side of microaggressions and someone waging a low-key war against members of the workplace, many who look like our readers. Coupled with high-stakes mid-term elections in Georgia on the heels of repealing the right for women to access their full reproductive healthcare, the “new normal” is anything but “normal.” Not having access to our full reproductive healthcare options has real consequences for Black women who are three times more likely to die in childbirth or the year following, regardless of class or education level. In this issue, we endeavor to give readers the information you need to know what to focus your attention on, to make good decisions and to quell fears about the unknown.

In this issue, you’ll learn more about monkeypox and the vaccine, COVID-19 vaccine clinical trials at Morehouse School of Medicine, legislation being put in place to curb maternal mortality, and what expectant mothers can

do to improve their chances of survival during and after childbirth. You’ll learn about Diversity in Aquatics, a network committed to making sure African Americans, who were historically banned or dissuaded from learning to swim, can now find out where to take lessons, learn to swim and join swim teams. As we endeavor to make better food and beverage choices as the holiday season approaches, readers will explore kombucha, a twist on sweet tea that is a delicious and healthy alternative to the Southern staple. Coupled with the benefits of walking, there’s no reason we can’t keep those A1C levels in check as we move into the Merry and cheerful season. We’ll also look at how Jackson, MS is bouncing back from the latest water crisis, why so many Black women suffer from alopecia and what’s being done about it. While October ushers in the season of change, we can’t turn away from the topic of domestic violence, particularly with a repeat offender running for Senator of the great state of Georgia. October is Domestic Violence Awareness Month, so Dr. Kanika Bell will help readers understand how this happens, what’s at stake and where to get help.

Armed with all of this insight and information, we hope readers will understand the more you know, the better you will feel. On the subject of feelings, if it doesn’t feel right in terms of physical, emotional or spiritual health, then say something or do something. Advocate for yourself and others. As we march toward the end of the year, let’s make sure we get there as healthy and whole people, and most importantly, we get there together.

Love and light, Nsenga

Nsenga

Nsenga K. Burton, Ph.D., is founder & editor-in-chief of The Burton Wire, an award-winning news site covering the African Diaspora. A writer, scholar and thought leader, Dr. Burton has served as editorat-large for The Root, editor-in-chief of Rushmore Drive (IAC), cultural critic for Huffington Post and Creative Loafing, and culture and entertainment editor for Black Press USA Newswire.

Janis

James

Clayton

Cindy

Christopher

Josina

Donecia

By Josina Guess

By Josina Guess

What are you drinking? Sweet tea, coke, or lemonade? Beer or a cocktail?

Coffee or tea?

They might taste good, but sugary, highly caffeinated, and alcoholic beverages can leave you feeling bloated, wired, or tired. Kombucha, a lightly carbonated beverage made from fermented sweet tea and often infused with natural flavors, makes a great alternative for your cup. If you haven’t tried kombucha, you may want to give it a taste. If you’ve tried kombucha and found it too vinegary, consider a small, locally brewed and reliable source.

Erika Galloway, co-founder of Figment in Athens, Georgia, didn’t like kombucha the first time she tried it. “This is awful,” she said. It tasted too much like vinegar.

Galloway, who had been working with beer for years, was interested in taking on a new challenge. The friend who offered her that first funky taste of kombucha thought Galloway might be able to figure out how to make it more tasty. Galloway and co-founder Jason Dean, who also had experience in beer-making, took on the challenge, and together they developed kombucha recipes that are refreshing, flavorful, and smooth.

It’s no surprise that Galloway thought kombucha tasted like vinegar. If it is left to ferment too long, kombucha will become vinegar. Galloway noted that the kombucha sold in most grocery stores is made

in such large batches it is hard to regulate the acidity.

At Figment, they ferment their kombucha in small batches, using stainless steel containers designed for beer. Although kombucha can produce its own bubbles, Galloway says they add carbonation so the batches don’t over-ferment. This protects delicate flavors, and keeps the vinegar taste at bay.

Many people turn to lacto-fermented foods and kombucha as a health tonic because it is high in antioxidants, probiotics, and vitamin B. “It helps to populate your gut with flora,” Galloway said.

The sweeteners used to ferment kombucha are consumed in the fermentation process and the alcohol content is “under .5%,” Galloway says. Colors and Shapes, one of Figment’s offerings, is infused with dry hops. It has a flavor similar to beer, but none of the side effects. “There’s nothing beneficial about beer,” Galloway notes. Some home-brewed kombuchas can have higher alcohol content, so it is important to check your sources.

More research is needed to verify all of kombucha’s benefits and risks. But we do know the hazards of drinking sugary sodas, alcohol, and too many caffeinated drinks. According to the CDC, “weight gain, obesity, Type 2 diabetes, heart disease, kidney diseases, non-alcoholic liver disease, tooth decay and cavities, and gout, a type of arthritis,” are all associated with regular consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages. And the adverse effects alcohol has on our brain, heart and liver function along with that tell-tale “beer gut” are well-documented. Too much caffeine can cause insomnia, tremors and headaches. Although it can vary depending on the tea used and the exact production process, kombucha generally contains about one-third of the caffeine content of a regular cup of tea, offering the antioxidant benefits of tea without the tremors.

With an open taproom and tastings of flavors like Orange Blossom, Strawberry Meyer Lemon and Blueberry Lavender, you might discover a flavor that suits your palate. And you may get to the bottom of that cup or can and feel good inside.

Figment is located at 1085 Baxter St. in Athens, Georgia, and may also be ordered online or available at a market near you.

Josina Guess is a writer based near Athens, Georgia. She is a contributor to several publications, including the anthology Bigger Than Bravery: Black Resilience and Reclamation in a Time of Pandemic (Lookout Books) September 2022.

The Black Directors Health Equity Agenda held their annual conference in Atlanta, October 3-4, 2022 at the Whitely Hotel and Morehouse School of Medicine. The twoday conference was marked by panels and discussions addressing health disparities in the African American community with special attention being paid to hospital boardrooms, patient care and issues like maternal mortality. African American women are three times more likely to die in childbirth or within a year following childbirth, regardless of class or educational status.

“Aftershock” director and producer Tonya Lewis Lee; Black Women’s Health Imperative President and CEO Linda Goler Blount, MPH; Natalie D. Hernandez, Executive Director of the Center for Maternal Health Equity at Morehouse School of Medicine; and Dr. Rachel Villanueva, Immediate Past President of the National Medical Association, participated in a robust discussion about maternal mortality and bias against Black and Brown patients, and strategized about what could be done to improve outcomes.

Moderated by Lauren R. Powell, Vice President of

Dr. Rachel Villanueva, Immediate Past President of the National Medical Association Talks Maternal Mortality

the U.S. Health Equity and Community Wellness at Takeda Pharmaceuticals USA, the activist-oriented discussion made it clear that the rate of maternal mortality impacting African American women means we are in a crisis and radical change must happen.

Audience members shared their personal stories, with one gentleman discussing how his mother died in childbirth and how that economically devastated his family. Another audience member praised the activism of the panelists while suggesting the need for more data and the inclusion of more voices in the discussion like practitioners.

Following the panel, I had an opportunity to connect with Villanueva, who has made combatting health inequities and maternal mortality her life’s work. Like many others who set their sights on medical school, Villanueva “just wanted to be a doctor,” but was called to do this difficult work after seeing such a great need.

“I really liked women’s health and maternal health because you could really follow women through their whole life course. I’ve had some patients that were patients of mine before they went to college and now they are having babies. Just having that continuity with a person really is a very special relationship that not all physicians can have,’ says the Clinical Assistant Professor of Obstetrics/Gynecology at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine.

The ability to stay with patients for the duration of their care should not be taken lightly considering African Americans were often barred from seeking treatment at some hospitals and Black doctors were also barred from practicing. “We were not allowed to practice medicine or take care of patients and the disparities existed a long time ago. I think that really fueled my desire to make a change, to understand that we’re dealing with stuff we’ve been dealing with for 50-plus years or a hundred years when you’re talking about disparities in maternal health,” adds Villanueva, who “wanted to be part of the solution.”

Villaneuva’s signaling that maternal mortality and Black women is not new is important since the fact that maternal mortality and Black women is a trending topic might suggest it’s a recent phenomenon.

Bias against Black expectant mothers is not new; what is new is the high-profile people who are talking about it publicly and making it newsworthy in the process.

We’re seeing more and more information about maternal mortality with the success of Lee’s critically acclaimed documentary, “Aftershock,” and with more people taking an interest in the subject after Serena Williams, often regarded as the greatest athlete of all-time, discussed how she almost died in childbirth because her doctors didn’t listen to her complaints. If one of the greatest athletes walking the Earth almost died in childbirth, then what does that mean for the rest of us? It means expectant mothers can learn from her – to advocate for yourself.

After giving birth, Williams began to lose feeling in her legs. And her pain increased. Having suffered from blood clots in 2011, Williams sensed something wasn’t right. Despite the hospital staff, including her doctor, insisting she

was fine, the world champion insisted they test her for blood clots since she had been forced to go off of her medication during the birthing process.

After the test, they found the clots, rushed her into surgery and saved the tennis phenom’s life. Had she not advocated for herself, she very well may not be here to raise her beautiful daughter Olympia.

Villanueva agrees that patients have to advocate for themselves or have someone advocate for them. One of those steps is choosing the right doctor. “I think you really need to have someone who understands you and makes you feel comfortable,” the women’s health advocate says. “I think (it’s about) finding someone you can be comfortable with who answers your questions, who takes the time to listen, who you feel does not dismiss what you’re saying and gives you credible information,” she adds.

While Villanueva thinks it’s a good idea to find a doctor who looks like you

because research shows that it helps tremendously with communication and care, not having a Black or Brown doctor is not a dealbreaker, especially for those who don’t have access to Black doctors. “If you don’t feel comfortable with a doctor, maybe not the first time, but after you’ve had a session or two, then maybe it’s time to look for somebody else,” Villanueva adds.

The immediate past president of the National Medical Association, the largest and oldest national organization representing African American physicians and their patients in the United States, also wants changes in policy. She references the recently passed Momnibus Act, a bill that directs multi-agency efforts to improve maternal health, particularly among racial and ethnic minority groups, veterans, and other vulnerable populations. It also addresses maternal health issues related to COVID-19. “The Momnibus, that really looks at the roots of all the social determinants

like mental health, research, data collection. It (the act) is not only social services; it is really getting down to data. It says to make sure we understand the problem well, and let’s make sure we have the data and the research so that when people ask for it, and people are data-driven, we can give them answers,” the reproductive justice expert adds.

The women’s health expert wants the medical community to understand that taking care of patients doesn’t just happen in the hospital. “All those social determinants, all those structural issues, all those barriers to access –those are things that we really need to be able to take care of patients and to eliminate those disparities and to ensure people have optimal health,” she notes. “The benefit of conferences like these is to raise awareness, raise money and to build strategies that will help eliminate maternal mortality.”

The

Since 2020, there’s never been more awareness of the importance of immunizations.

More than ever before, Black doctors were on the front lines of scientific research regarding immunizations against the COVID-19 pandemic. Dr. Kizzmekia Corbett introduced a relatable understanding of vaccinations, and though many were proud of her efforts, there was a significant portion of the community that was decidedly “anti-jab.” “Anti-vaxxers,” as they came to be called on social media platforms, took to the internet asserting that the COVID-19 vaccination was everything from an under-researched science experiment, to a purposeful concoction derived from an evil plot to mutate the human population. But what is behind the mistrust? Why is vaccine hesitancy among African Americans so great now?

The historical research on the psychology of anti-vaccination views is vast. Recently, the anti-vax position is a meeting point between two highly unlikely bedfellows: radical white conservatives and allegedly racially conscious Black Americans. How did these two diametrically opposed camps suddenly stand shoulder-to-shoulder on an issue? Though for different reasons, both agree on one key point: there

is reason to distrust the American government. The American healthcare system has been wrought with problematic interactions with the Black community since Africans first arrived in the Americas. But this particular mistrust was, has, and is costing Black lives.

When the pandemic began, there was a myth in the Black community that COVID-19 was a disease that, finally, impacted people of European descent more than people of African descent. However, many knew that there was truth to the old adage, “When White folks get a cold, Black folks get the flu.” Knowing that the persistent health and environmental disparities would put Black people at a disadvantage, Black doctors reasoned correctly that Black people would die from COVID-19 at a higher rate. Even with this hypothesis being proven and Black COVID-related death on the rise, vaccine hesitancy continued. It seemed ludicrous to some that vaccines could be developed that quickly. The truth is the human coronavirus has been studied for decades. Another truth is that technology and science move at a faster pace these days, so the development of a preventive strategy was in greater reach. However the truth that America has had a very shady relationship with Black healthcare also pervaded. Though what hap-

“When White folks get a cold, Black folks get the flu.” There is truth to the old adage, says Dr. Kanika Bell

pened to Henrietta Lacks and the Black men in Tuskegee had nothing to do with vaccines, they are symbols of systemic racism in the American healthcare system, and justifications for distrust.

Last fall, I studied the differences between white and Black college students regarding adherence to COVID-19 campus policies and the overall institutional policy differences at Historically Black Colleges and Universities versus Primarily White Institutions. I found HBCUs to be more rigorous in terms of vaccine mandates and Black students at HBCUs were more adherent to vaccine policies, even more than Black students at PWIs. This may indicate that, for African Americans, the suggestion of vaccination isn’t the motivating or mitigating factor; it is who is making the suggestion. Having Black faces at the forefront of vaccine research and information dissemination likely moved the nee-

dle for far more Black Americans than it would have without them. But more were needed.

Let’s not forget that Civil Rights 2.0 and COVID-19 occurred simultaneously. Classical conditioning is a psychological concept that suggests that when two unrelated stimuli are presented together, they become linked in the mind of the observer. It’s why Pavlov’s dog salivated to the sound of the bell even when food wasn’t present. For many, the same government that viewed Black lives as expendable at the hands of police and vigilante white citizens was now providing guidance on how to allegedly save Black lives via a vaccine. Classical conditioning operated widely, as bits of misinformation resulted in ubiquitous illusory correlations.

Social media posts about how people allegedly “died after the jab” and no statistics about how many people are alive because of it, celebrities circulating myths regarding the vaccine, and a lack of overall Black representation in the medical professions, all contributed to continued anti-vax views. It is critical to note in this analysis that Black people don’t hate science, but Black people are more likely to look to their own chosen leaders for guidance in these situations, and Black people remember systemic mistreatment. Black people remember how racism has previously guided medical interventions and they remain suspicious. To truly address the nature of Black anti-vax views, we have to consider their cultural context and how to blend healthy skepticism with scientific truths.

“Black people can't swim” is a negative stereotype that has stuck around for years, and highlights the potentially negative relationship between Black people and water. However, director and Emmy Award-winning filmmaker Cathleen Dean challenges that notion with her documentary, “Wade in the Water: Drowning in Racism.” The film reveals the history behind how Black people were kept out of the water due to racism and uncovers the special connection people of color have had with water. As a result, Dean wants “Wade in the Water” to motivate more Black people to embrace the water and to encourage them to add swimming and other water activities into their daily routines.

"The impact I'd like to leave on every audience that sees the film is that everyone should know how to swim. It's unacceptable that Black children are drowning at six times the rate of Caucasian children,” Dean said. “As a community, we need to connect to the water for health, spirit, spirituality, and wellness. When there isn't a connection, it is a huge loss."

“Wade in The Water: Drowning in Racism” premiered in 2021 at the Roxbury Film Festival in New England. The film has had a remarkable run as it has screened at multiple festivals, including the Miami International Film Festival, The World House Documentary Film Festival at Stanford University and San Francisco Art House Film Festival. “Wade in the Water” also aired on PBS and won an Emmy in the Societal Concerns category. Most recently, the documentary was featured at the

“Showing at Morehouse College is huge for me. It’s huge for Diversity in Aquatics.”

— Cathleen Dean

"Showing at Morehouse College is huge for me. It's huge for Diversity in Aquatics. They are an organization trying to restore the swimming programs at HBCUs across the country,” Dean said. “Morehouse College revamped its swimming program. So it's super special that the film is going to screen there."

“Wade in the Water” highlights the historical, spiritual, and cultural connection people of African descent have always had with the water. The film also explores the protests in Broward County, Florida to desegregate the beaches and pools.

Dean was inspired to create the film

when she took swimming lessons to train for her first triathlon. She joined the non-profit organization Diversity in Aquatics for swimming classes where she encountered Bruce Wigo, CEO and president of the International Swimming Hall of Fame. Wigo showed Dean an art exhibition he curated that chronicles the history of Africans and swimming.

"It was such an amazing exhibition; it spoke to me as an artist on so many levels. I want to share that story with the community and, hopefully, with the world that we had a very strong cultural connection with the water. Africans were the preeminent swimmers of their day before the slave trade and Jim Crow segregation," Dean

said.

The documentary has left an impression on those who have seen it. She said people have either picked up or returned to swimming after they watched “Wade in the Water.” In fact, Dean explained how people approached her a while after the screening and shared how they got back into the water.

"I know of people who may have swam as a child but then started swimming again as an adult for health and wellness. It's important to educate people who may not realize why their families didn't have a swimming tradition. It's highlighted in the film that if parents didn't swim, they would encourage children not to go by the water as a form of protection," Dean said.

Swimming is one of the best exercises anyone can do. It is a full-body workout with no impact on your joints or knees. According to Harvard Health Publishing, water supports and cushions the body. Also, swimming is often recommended for people with arthritis and other chronic conditions. The CDC adds that people are able to exercise longer in water than on land because of the lack of pressure on the joints. Even better, swimmers have about half the risk of death compared to inactive people.

What's next for Dean is telling more water stories of people of color. She’s received the Artist Innovation Grant from Broward County’s cultural division and shooting has already begun for her next film, “Water is Medicine.” Dean is taking a plunge on this subject so more people of color can see the beauty of the water.

Mention domestic violence or intimate partner violence, and one often imagines the victim as a middle class American-born white woman in her 30s, a housewife who is controlled by her husband but out of options due to being financially reliant upon him to care for her and their children.

No matter how heroic or tragic the outcome, the faces of IPV have been similar. From Nicole Brown Simpson to Francine Hughes, the game-changing, policy-influencing cases have historically involved a single demographic – white American women.

Though they winced at the scenes depicting violence in “What’s Love Got To With It,”viewers still convinced themselves that this story was not tragic because of how Tina Turner turned out, how strong she was to survive and thrive after such turmoil. But Tina Turner suffered a trauma.

Just last year, she told Vanity Fair that she still has nightmares about the abuse she suffered, more than 40 years after escaping her abusive relationship. Though the film received critical acclaim, unlike “The Burning Bed,” no policies were adopted due to the awareness it raised. As famous as Tina Turner’s story was and is, she is still not the face we imagine when considering victims of IPV.

Data suggests that the mental health consequences related to being involved in a violent relationship are numerous and long-lasting. Post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, depression, and chronic interpersonal problems are not uncommon among those who have been abused in an intimate relationship.

To add insult to injury, the shame and invisibility experienced by many victims of IPV presents yet another mental health challenge. Those that don’t immediately come to mind as a prototype victim may feel as though their lives and experiences are unimportant, and that there are no resourc-

es available to address their particular needs. During October, Domestic Violence Awareness Month, it is important to focus on the mental health effects of those most vulnerable to IPV and their after-effects.

Though we all can name Black women who have suffered at the hands of an intimate partner, (Essence Magazine even published a list of Black celebrities impacted by IPV), there persists the misconception that Black women experience IPV less frequently, and when they do, the deleterious effects are moderated by Black women simply being “strong.”

That is dangerously false. Dan-

Physical and verbal violence, emotional manipulation, financial abuse, and the impact of interlocking systems of compounded oppression make for a particular kind of violence that takes place in Black women’s relationships that goes virtually ignored. The forgotten Black women, even within the Black woman community, have it even worse. Transgender Black women, Black women sex workers, and Black women immigrants face an even higher risk of IPV and higher death rates.

Not considered in dismissive suggestions to “just call the police,” are the inherent psychological and social challenges involved in a person filing a domestic abuse charge against someone of the same gender, someone a victim fears may suffer lethal consequences once the police are involved, or by someone who fears her children being removed by child services. The lack of support and resources can lead to learned helplessness for Black women: a failure to attempt to help one’s situation due to the belief that it cannot improve.

gerously, because family members, friends and police officers tend to take the abuse of Black women less seriously, though it is a leading cause of death for Black women. Dangerously, because Black communities too often adopt a mind-your-business, no-snitching response to IPV, though Black women are more than twice as likely to be murdered by male partners than White women. Dangerously, because prevention and intervention strategies fail to account for the unique challenges of Black woman IPV victims, though a significant amount of Black women’s suicidality is related to IPV.

Promoting education and screening programs, raising awareness, and engaging efforts to decrease family poverty to prevent and treat IPV, is certainly a start. But Black women have additional barriers to support when coping with IPV. We must demand culturally relevant services in the most vulnerable communities. We must abandon the idea that “it’s not our business” when we see IPV in our arenas. We must reduce the urge to judge or criticize Black women victims, beholding them to the “strong Black woman” narrative. We must acknowledge that intimate partner violence happens to Black women in order to facilitate healing.

If you are experiencing domestic violence or know someone that is experiencing domestic violence, contact the domestic violence hotline to get help. Call 1-800-799-7233 or text START to 88788.

Black women are empowering themselves with knowledge, birthing plans, doulas and midwives

by K. Anoa MonshoThey call them “near misses,” women who almost died while giving birth. It is a harrowing experience that, over time, sinks below the surface but never disappears. Nearly every Black woman I spoke to about their hospital birth could relate. Few described a peaceful, emotionally beautiful miracle like the birthing center experience documented in the groundbreaking film, “Aftershock.”

The most important thing that Black women can do to empower themselves to have a positive and healthy birthing process is to proactively educate themselves well before delivery, according to labor and delivery nurse Lynnell Day. (Note: Day’s name has been changed to protect her identity.) Day has helped hundreds of women give birth in a hospital setting, but when it comes time for her to have a child, she plans to engage a midwife.

“It’s important to realize that modern obstetrics was built on a racist past where doctors experimented on the bodies of enslaved women in order to take over an area where other women, midwives, had been the experts for thousands of years,” she explained. Racism impacts the field today, notwithstanding Black OB/GYNs.

The assumption that women don’t know their own bodies, worry needlessly and therefore don’t need to be listened to, permeates the medical field. The current medical insurance model perpet-

Study reveals the impact of a total abortion ban would increase Black maternal mortality by at least 33%

uates that. “Selecting the right person to help you deliver your baby is crucial,” Day said.

Atlanta-based OB/GYN Dr. Melinda Miller-Thrasher agrees. “Doctors are people, too,” she said. After 35 years of delivering thousands of healthy babies to satisfied mothers, Miller-Thrasher – who is Black – is in high demand; the doctor is beloved for her nurturing and respectful demeanor. “Unfortunately, that means without training, we bring our unconscious biases to work just like everyone else. My job is to ensure a safe birth for mother and child, with the mother guiding the process. It’s her body, her baby, her birth experience.”

Not every doctor feels that way. Often, unnecessary interventions like breaking the water or administering Pitocin can lead inexorably to C-sections, a major surgery that most healthy women do not need and one that can cause dangerous complications during birth. Many women don’t want that kind of intervention, but it is common. That’s where having a doula throughout pregnancy can make a measurable, positive difference in the birthing experience.

“As a doula, I nurture not only the birthing person, but their family as well, helping to devel-

op and advocate for the birthing person’s vision of what they want their birth to be, whether that is at home, at a birthing center, or in a hospital,” Ilexis Lindsey says.

Engaging a doula as an advocate who knows what the birthing person wants and who will intervene when it is appropriate helps ensure a more positive experience. “Not everyone is able to have a home birth or birth center delivery; high-risk pregnancies should be attended to in a hospital, but for those who can, it’s a beautiful experience.”

When looking at data comparing the U.S. to other developed countries, the U.S. has the highest rates of maternal death and the lowest utilization of midwives and doulas. This nation has overly medicalized the birth process. Black and Brown women, poor and rural women without access to midwives and compassionate healthcare are dying as a result.

I had a midwife and a doula, but after days of hard-but-beautiful labor – in and out of the inflatable pool we had installed in my living room, walking endless loops around my favorite park, and surrounded by people I love – my son’s cord wrapped around his neck causing distress. I ended up in the hospital after all, need-

ing an emergency C-section. But, the midwife knew the doctors oncall and requested one – –A Black man – who listened carefully, explained everything to my satisfaction, and allowed the midwife and doula to stay in the room during the surgery.

The women arranged for me to have a private room and called a couple of my friends who brought my own blankets, pj’s, music and decorations to make me feel at home during the unplanned hospital stay. My doula and best friend, Taliba, alerted the nurses in the middle of the night when there was more blood than there should have been and dismissed a rude nurse, asking for another with more compassion as we struggled through the crisis. It wasn’t the home birth I’d planned, but I felt empowered thanks to the women at my side, a flexible birthing plan and a compassionate doctor who really listened to me even during what could have been a tragic ending.

Why are Black women still dying at higher rates than anyone else during childbirth and the days and weeks after giving birth? It’s complicated. But these are our sisters, daughters and friends who are at risk; it is us. The first step to turning the tragedy around is to arm ourselves with knowledge. I can’t think of a better way to start that process than watching “Aftershock,” and making sure everyone connected with Black women watches it too. It just might save someone's life.

Soleil Irving is a vivacious, gorgeous 5-year-old whose eyes, personality and flashing smile echo the mother who died before she was a month old.

“Soleil is so much like Shalon – smart, curious, loving, kind, determined, and fearless,” Wanda Irving said, comparing her granddaughter to the daughter she lost to a preventable postpartum death. “She loves her gymnastics, cooking, creative drama and karate classes. I can see Shalon in her eyes. Soleil has her mother's love of life, and she lives each day to the fullest. But in the quiet times, she so misses her mother.”

“You need to vote again, and again, and again or you can run for office and change your world. Voting matters!”

— Tonya Lewis Lee

Dr. Shalon Irving was an epidemiologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and a lieutenant commander in the US Public Health Service Commissioned Corps who worked fiercely to eliminate the health disparities caused by structural racism, limited healthcare options, trauma and violence.

“I see inequity wherever it exists, call it by name, and work to eliminate it. I vow to create a better earth!” Shalon declared in her social media bio. She was considered a brilliant researcher, making history at age 25 when she earned the first dual Ph.D. in sociology and gerontology from Purdue Uni-

versity.

Shalon understood the many underlying factors that lead to poor outcomes and used her voice and position to speak out on behalf of those who couldn’t advocate for themselves. None of her knowledge, accomplishments or passion helped when doctors ignored her distress and concern. She was a Black woman in America who died on January 28, 2017, just 21 days after giving birth to Soleil.

Shalon’s family, many friends and coworkers were stunned and devastated. They gathered, transformed their grief into action and created an organization to keep

Shalon’s legacy and work alive. Dr. Shalon’s Maternal Action Project partners with philanthropists, leading public health organizations, policymakers, legislators, and advocacy groups around the country to reduce maternal mortality rates, specifically in Georgia. They have developed two initiatives, “Knowledge is Power” and the Believe Her app that are beginning to have an impact.

“‘Knowledge is Power’ advances the birth justice agenda by focusing on high-risk Black women and birthing people, as well as providers, to improve community health awareness, education and empowerment and reduce systematic health inequities,” DSMAP board member Dr. Ndidiamaka Amutah-Onukagha says. “We’re working to empower black families with the skills and knowledge to navigate racist healthcare systems and ‘doctor-speak’ to obtain the best outcomes for themselves.”

DSMAP’s Believe Her app, which can be downloaded through Apple Store and Google Play, empower women in their healthcare journey by teaching them appropriate phrases when they are trying to get their doctors to listen and believe them.

Wanda Irving has surrounded Soleil with images and stories of her mother. The 5-year-old has a loving village of Shalon’s friends and family to help raise and guide her, but the loss of a mother she will never know is a deep wound and may always be.

Her grandmother is determined that she will thrive despite the pain they both share.

“My heart breaks when Soleil says that she wants to die so that she can be with her mommy in heaven,” Irving says. “She tells me daily how much she misses and loves her mom. It truly concerns me that this loving, sweet child will never ever get the chance to know her mommy. And we'll both live with the trauma of losing Shalon. Soleil will carry the pain throughout her life and potentially to the next generation.”

But Soleil is her mother’s child, Irving says. “She wants to be a doctor so she can help save Black women.”

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

COVID-19

•

By Kimberly Davis

By Kimberly Davis

he Morehouse School of Medicine in Atlanta has begun enrolling participants in a new clinical trial that seeks to study the safety and immune response of participants who have received vaccine boosters to combat emerging COVID-19 variants. MSM is one of 24 sites and four HBCUs to be selected for the COVID-19 Variant Immunologic Landscape trial by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, which is part of the National Institutes of Health.

Because African Americans and other people of color have been disproportionately impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, this trial — and others being conducted by the team at More-

house — is critical, says Dr. Lilly Immergluck, who co-directs the trial unit with Erica Johnson, Ph.D. While African Americans are quicker to overcome vaccine hesitancy than whites, our community still lags behind other racial groups with regard to COVID-19 vaccination rates partly because of what some consider to be a well-earned mistrust of the medical and science communities.

“More than some of these other institutions, we have to not only do our due diligence to roll out these studies, but we need to do our homework to understand every aspect of the pre-clinical data, the science that’s backing this up, because people are looking to us because we are a trusted

source to a community that has been disproportionately affected by COVID,” says Immergluck, professor of microbiology, biochemistry, immunology and pediatrics at MSM. “We recognize that as an HBCU we wanted to be a trusted source to our communities of color regarding COVID as far as the vaccine trials, as well as other therapeutic trials that are coming out.”

An increased level of trust in an HBCU is a sentiment echoed by Cshanyse Allen, CEO and director of Innovative Health Care Institute, an Athens, Georgia-based company that provides entry-level health care training. Allen, who holds a doctorate in nursing practice, says she and her team began

reflect the communities they aim to serve. Research has found that while Blacks make up about 13% of the U.S. population, we represent only 5% of clinical trial participants. Because communities of color continue to be hardest hit by COVID-19 — and for various reasons unrelated to vaccine hesitancy — HBCUs must continue to take the lead.

“If it’s affecting Black and Brown people disproportionately across the age spectrum, and you run these trials and there’s very few underrepresented communities in these trials, how can you say that the effectiveness and durability of these vaccines really work?” Immergluck asks.

providing COVID-19 testing and vaccinations at their clinic because of the lack of access to testing for African Americans in her community. There was — and still is — a great deal of mistrust, misinformation and fear.

“People were scared,” Allen recalls. “Having an HBCU that is leading the way on the research is going to be phenomenal for our community because that is really going to take off a layer of mistrust. Having people that look like you not just giving vaccines and treating you, but actually doing the research so that you can have solid information about us, what happens with us — this is going to be groundbreaking for our community.”

Historically Black medical schools and colleges like Morehouse are also doing their best to enroll participants in clinical trials that

That’s why the Morehouse School of Medicine vaccine trial unit aims to be more than that, according to Immergluck, who has worked at MSM for more than 17 years. The vaccine unit team is focused on science-first, people-centered engagement serving the communities that are often overlooked. “We want to make sure they understand all aspects of clinical trials, in general,” Immergluck says. “What trial makes sense and makes the most impact in improving health outcomes for underrepresented populations? Those are the trials that I’m interested in being involved in; that’s what we’ve been selective about doing.”

And even as overall vaccination rates continue to increase, variants keep cropping up. It is these variants that this latest clinical trial is focused on. The trial also monitors the health of trial participants because so much about the long-term effects of COVID-19 are unknown; the science is constantly changing, Immergluck says. “I say to our team that we have to stay true to the data and science. We don’t know what this virus can do.”

Unsafe water and all that comes with it — constant vigilance, extra expenses, and hassle — complicate every aspect of daily life for residents of Jackson, Mississippi.By Renuka Rayasam

I n mid-September, Howard Sanders bumped down pothole-ridden streets in a white Cadillac weighed down with water bottles on his way to a home in Ward 3, a neglected neighborhood that he called “a war zone.”

Sanders, director of marketing and outreach for Central Mississippi Health Services, was then greeted at the door by Johnnie Jones. Since Jones’ hip surgery about a month ago, the 74-year-old had used a walker to get around and hadn’t been able to get to any of the city’s water distribution sites.

Jackson’s routine water woes became so dire in late August that President Joe Biden declared a state of emergency: Flooding and water treatment facility problems had shut down the majority-Black city’s water supply. Although water pressure returned and a boil-water advisory was lifted in mid-September, the problems aren’t over.

Bottled water is still a way of life. The city’s roughly 150,000 residents must stay alert — making sure they don’t rinse their toothbrushes with tap water, keeping their mouths closed while they shower, rethinking cooking plans, or budgeting for gas so they can drive around looking for water. Many residents purchase bottled water on top of paying water bills, meaning less money for everything else. For Jackson’s poorest and oldest residents, who can’t leave their homes or lift water cases, avoiding dubious water becomes just that much harder.

Jackson’s water woes are a manifestation of a deeper health crisis in Mississippi, whose residents have pervasive chronic diseases. It is the state with the lowest life expectancy and the highest rate of infant mortality.

“The water is a window into that neglect that many people have experienced for much of their lives,” said Richard Mizelle Jr., a historian of medicine at the University of Houston. “Using bottled water for the rest of your life is not sustainable.”

But in Jackson an alternative doesn’t exist, Dr. Robert Smith said. He founded Central Mississippi Health Services in 1963 as an outgrowth of his work on civil rights, and the organization now operates four free clinics in the Jackson area. He often sees patients with multiple health conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, or heart problems. And unsafe water could lead to death for people who do their dialysis at home, immunocompromised individuals, or babies who drink formula, Smith said.

Residents filed a lawsuit this month against the city and private engineering firms responsible for the city’s water system,

claiming they had experienced a host of health problems — dehydration, malnutrition, lead poisoning, E. coli exposure, hair loss, skin rashes, and digestive issues — as a result of contaminated water. The lawsuit alleges that Jackson’s water has elevated lead levels, a finding confirmed by the Mississippi State Department of Health.

While Jackson’s current water situation is extreme, many communities of color, low-income communities, and those with a large share of non-native English speakers also have unsafe water, said Erik Olson, senior strategic director for health and food at the Natural Resources Defense Council. These communities are more frequently subjected to Safe Drinking Water Act violations, according to a study by the nonprofit advocacy group. And it takes longer for those communities to come back into compliance with the law, Olson said.

The federal infrastructure bill passed last year includes $50 billion to improve the country’s drinking water and wastewater systems. Although Mississippi is set to receive $429 million of that funding over five years, Jackson must wait — and fight — for its share.

And communities often spend years with lingering illness and trauma. Five years after the start of the water crisis in Flint, Michigan, about 20% of the city’s adult residents had clinical depression, and nearly a quarter had post-traumatic stress disorder, according to a recent paper published in JAMA.

Jones, like many locals, hasn’t trusted Jackson’s water in decades. That distrust — and the constant vigilance, extra expenses, and hassle — add a layer of psychological strain.

“It is very stressful,” Jones said.

For the city’s poorest communities, the water crisis sits on top of existing stressors, including crime and unstable housing, said Dr. Obie McNair, chief operating officer of Central Mississippi Health Services. “It’s additive.”

Over time, that effort and adjustment take a toll, said Mauda Monger, chief operating officer at My

Brother’s Keeper, a community health equity nonprofit in Jackson. Chronic stress and the inability to access care can exacerbate chronic illnesses and lead to preterm births, all of which are prevalent in Jackson. “Bad health outcomes don’t happen in a short period of time,” she said.

For Jackson’s health clinics, the water crisis has reshaped their role. To prevent health complications that can come from drinking or bathing in dirty water, they have been supplying the city’s most needy with clean water.

“We want to be a part of the solution,” McNair said.

Community health centers in the state have a long history of filling gaps in services for Mississippi’s poorest residents, said Terrence Shirley, CEO of the Community Health Center Association of Mississippi. “Back in the day, there were times when community health centers would actually go out and dig wells for their patients.”

Central Mississippi Health Services had been holding water giveaways for residents about two times a month since February 2021, when a winter

storm left Jackson without water for weeks.

But in August, things got so bad again that Sanders implored listeners of a local radio show to call the center if they couldn’t get water. Many Jackson residents can’t make it to the city’s distribution sites because of work schedules, lack of transportation, or a physical impairment.

“Now, all of a sudden, I am the water man,” Sanders said.

Thelma Kinney Cornelius, 72, first heard about Sanders’ water deliveries from his radio appearances. She hasn’t been able to drive since her treatment for intestinal cancer in 2021. She rarely cooks these days. But she made an exception a few Sundays ago, going through a case of bottled water to make a pot of rice and peas.

“It’s a lot of adjustment trying to get into that routine,” Cornelius said. “It’s hard.”

The day that Jackson’s boil-water advisory was lifted, Sanders was diagnosed with a hernia, probably from lifting heavy water cases, he said. Still, the following day, Sanders drove around the Virden Addition neighborhood with other volunteers, knocking on people’s doors and asking whether they needed water.

He said he has no plans to stop water deliveries as Jackson residents continue to deal with the longterm fallout from the summer’s crisis. Residents are still worried about lead or other harmful contaminants lurking in the water.

“It’s like a little Third World country over here,” Sanders said. “In all honesty, we will probably be on this for the next year.”

Kaiser Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at Kaiser Family Foundation. KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

With new data showing that people at risk for monkeypox who are unvaccinated were 14 times more likely to become infected with the virus, Atlanta public health officials and workers say it’s important to remain cautious and use all mitigation measures.

And nearly six months into the outbreak, scientists haven’t reached consensus around many aspects of the monkeypox virus in the United States, which fuels uncertainty, fear, misinformation and stigma.

“There’s a lot that we actually don’t know about how the virus that’s operating in this particular outbreak functions,” says Justin Smith, director of the Campaign to End AIDS at Positive Impact Health Centers in metro Atlanta, one of the largest HIV service organizations in Georgia. “It’s behaving differently than the ancestral strains of monkeypox that we’ve seen that are endemic to parts of West and Central Africa.”

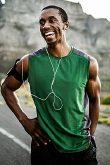

Monkeypox is a disease that is caused by infection with the monkeypox virus, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. People with monkeypox get a rash – which can originally look like pimples or blisters and may be itchy or painful – that may be located on or near the genitals and could be on other areas like the hands, feet, chest, face, or mouth.

Other symptoms of monkeypox can include fever, chills, swollen lymph nodes, exhaustion, muscle aches and backache, headache and respiratory issues, such as sore throat, nasal congestion or cough. Before this spring, monkeypox was rarely reported outside of the African continent, with the first case being reported in the United States in May. The disease has since spread to all 50 states, Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico, with the U.S. having the most confirmed cases in the world.

Georgia ranks fifth in monkeypox infections among all U.S. states behind California, New York, Florida and Texas, according to CDC data. As of Sept. 28, Georgia’s Department of Health reported 1,784 cases. As of that same date, more than 25,000 people have been issued a single dose of the Jynneos vaccine, and more than 14,000 people have received two doses. As with public health generally, the Black community is hardest hit. More than 77% of those infected were Black or African American and just under half of those vaccinated were Black or African American. This disparity is largely driven by lack of access to health care, stigma around sex and sexuality, and shame, according to Smith.

“Sadly, but unsurprisingly, what we have seen with monkeypox is that it has been concentrated primarily within Black communities here in Georgia — specifically among Black, gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men,” says Smith, who is a member of the White House Working Group on Monkeypox Equity. “So the risk is not distributed equally across the population.”

In Dekalb County, there have been 373 confirmed cases of monkeypox, according to the county’s latest internal report. In Fulton County, infection rates began to decline in August and have since leveled off, says

“There’s a lot that we actually don’t know about how the virus that’s operating in this particular outbreak functions.“

— Justin Smith

Dr. David Holland, the chief clinical officer for the Fulton County Board of Health. But until those levels reach zero or effectively zero, Holland says the county will try to vaccinate as many people as possible.

“The population of individuals we are trying to vaccinate, fortunately, respond very well to vaccines. There’s the people that demand the vaccine and stand in line to get it and there’s the people that will get it if it's right in front of them,” says Holland, who is also an associate professor at the Emory University School of Medicine. “We are seeing less of a demand for the vaccine, but it’s not going to zero and we’re still having a lot of success by taking it out to venues.”

One such outreach effort was at Atlanta Black Pride in September, where almost 4,000 monkeypox vaccine doses were administered. With the virus disproportionately affecting African Americans – specifically Black, gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men – officials say this pivot in strategy is essential to reaching the communities that are most at risk. But that doesn’t mean that others cannot become infected by the virus.

“It is true that monkeypox disproportionately impacts members of the Black LGBTQ community, but you don’t have to be gay to get monkeypox,” Smith says. “That’s really important for people to know.”

Holland says it’s also important to know how people are becoming infected with the monkeypox virus. It is not transmitted by casual contact, such as at the grocery store or on public transportation, he says. Rather, transmission requires prolonged, intimate or skin-to-skin contact. “If you’re not in or in close proximity to one of the risk groups, your risk of getting it is pretty low to zero. That said, the virus is still a virus. It can affect anyone, so we’re working really hard to eliminate the disease before it gets into the general population,” he says.

It’s also important to understand that there are countermeasures: the two-dose Jynneos vaccine, testing and the investigational treatment Tecovirimat, also known as TPOXX, are the major efforts at mitigation that are currently available, although not as readily accessible as they should be, according to Smith.

Swimming is not only a great exercise, but also a key that opens the door to job opportunities and unique aquatic experiences. However, for people of color, this option is not always presented to them.

According to The University of Memphis and USA Swimming, 65% of Black children have little to no swimming ability. This information explains why drowning is one of the leading causes of death in young Black children.

Diversity in Aquatics is an organization trying to solve that problem. They encourage and teach people of color to swim no matter their age. They follow up with the direction, resources, and people who are passionate about the water. In other words, DIA provides the key to that door of opportunities.

"Diversity in Aquatics is a network of people that care about you and care about the cause. We don't see not being a swimmer as a deficit; we see it as a chance to make you a swimmer and the opportunities that come after it," said Dr. Miriam Lynch, Executive Director of Diversity in Aquatics

DIA was founded in 2010 by Dr. Shaun Anderson and Jayson Jackson, has more than 2000 members nationwide and includes a $25 annual membership fee. Their main goal is to empower communities to access quality water safety education and aquatic opportunities.

Lynch explains the current statistics of Black people's

inability to swim is the result of history.

During the Civil Rights era, swimming was among the many items that Black people were banned from participating in.

Going back in history, Lynch elaborates that slave masters manipulated Black people's relationship with water and used it as a tool of fear.

"We were very adept swimmers. Water was part of our culture, and we participated every day. During the transatlantic slave trade, water was seen as fear. It was seen as a way where slave masters would drown people purposefully to show that you couldn't go across that border, and you couldn't participate and have the joy or the religion of water. It was a way to separate people from their roots," Lynch said.

DIA is connecting people to the water by finding their water-related needs and forming aquatic councils to meet their needs. These subgroups within DIA provide education and activities for water-related interests. Members can join committees for scuba diving, swimming, triathlon training, and HBCU swimming. Adapted Aquatics is a unique counsel among the rest as they serve the water needs of those with disabilities and special needs.

Adrienne Wesley is the co-chair of the Adapted Aquatics council. She was a special education teacher for more than 10 years and transitioned those skills to be a special education water instructor. She dove into this line of work because

she saw how swimming benefited her son when he had sensory issues. Her son's therapist prescribed swimming as a treatment.

Now, Wesley and the members of the Adapted Aquatics council work with more therapists to help children with special needs. They even hosted a certification class to become a special education water instructor at Emory University in Atlanta. The program is called “Sensory H2O.” Wesley partnered with Emory University's Department of Physical Therapy and the National Association of Black Physical Therapists to train doctoral and physical therapy students in special education water instruction. The goal is to create more representation in an overlooked space.

"It's just something that I just fell into. Very few programs, especially Black programs, are for people with special needs. I committed to this role so people can access this resource," Wesley said.

The biggest objective for DIA currently is reactivating the swim teams at HBCUs. Howard University is the only HBCU in the nation with an active swim team, and lack of support from the administration is the most common reason why HBCUs no longer have the programs. In the past, the swim teams were known for having the most remarkable athletes at the schools. In the 1980s, 21 swim programs at HBCUs nationwide would teach swimming and diving.

"We are bringing back aquatics to historically Black colleges and universities as well as Hispanic-serving and tribal institutions. We know that these institutions are the center points of communities and research, and they are the great community magnet in a way that can help to change the statistics today," Lynch said.

On December 17, DIA will host an HBCU swim meet for students and alums at Morehouse College during the HBCU Celebration Bowl weekend to raise funds for their initiative.

"We're raising money to go back to HBCUs. We had a young man from Fisk University contact us about the lack of a swim team at the school. Our swim meet is his chance to test what he has been practicing and represent Fisk University. That's what it is all about," Lynch said.

Dermatologist Danita Peoples-Peterson says some styles are causing hair loss, and tight braids are at the top of her list.

In a time when the culture is raving about natural hair and lawmakers are making it illegal to discriminate against it in the workplace, what’s causing so many Black women to have alopecia?

Dr. Danita Peoples-Peterson, a dermatologist practicing in Midland, Michigan, says it has a lot to do with the choice of hairstyle, but there are other reasons, too.

“Alopecia is just a medical word that describes hair loss,” she says.

There are several types of alopecia, but traction alopecia is the most common to affect Black women. The condition is caused by wearing tight hairstyles, using heat, and applying chemicals. One-third of women of African descent who wear these “traumatic hairstyles” are affected by the condition.

Peoples-Peterson says wearing tight weaves and extensions or styles that pull the hair back at the edges, like high ponytails, can play a role in hair loss.

“The main thing that happens to us, Black women, as far as traction alopecia is concerned, is the continued application of heat, especially to the edges — the front edges,” she told Word In Black in a phone interview. “And wearing your hair in really tight braids.”

Peoples-Peterson encourages Black women to be sure the “protective styles” they choose actually protect their hair. For example, she recommends exploring other options, like crochet braids, rather than going with individual braids or plaits.

“You would cornrow your hair and then just crochet the extra

hair on top and leave it like that,” she says. “And in that state, you wouldn’t have to put heat on it all the time or chemicals.”

Wigs also made the cut because they don’t cause tension or require heat.

While some of the no-no styles Peoples-Peterson mentioned are still popular, the Wayne State University professor believes things are turning around, and the Black community is embracing natural, healthy hair.

“Maybe there’s less social pressure to wear your hair straight. And as a consequence, there’s less hair breakage, less scarring alopecia, less traction alopecia,” she says.

And contrary to the belief that Black hair doesn’t grow, she says

“Contrary to the belief that Black hair doesn’t grow, [Peoples-Peterson] says embracing natural hair can help the hair “attain a longer length too.”

embracing natural hair can help the hair “attain a longer length, too.”

According to a 2018 Mintel report on the Black haircare market, 40% of Black women reported they were most likely to wear their hair with no chemicals or added heat. And 33% said they’d wear their natural hair, but with added heat.

The report also noted that hair relaxer sales have dropped by 22.7% since 2016.

Things were different when Peoples-Peterson was a kid. She recalls suffering from traction alopecia at age 2 and being discouraged from wearing her natural hair at home and school.

On top of being expected to straighten her hair, there were times when her family told her that she didn’t have “good hair.”

By the time she was in high school and college in the ‘70s and ‘80s, she was rocking her hair in an afro or short haircut.

Now, she encourages parents to “say things that will make (their children) feel more confident about how their hair looks in a natural state,” so they won’t feel unattractive.

And for Black adults, she encourages them to accept themselves as they are “because then, you wouldn’t feel obligated to do as much traumatic or damaging things to your

hair or scalp.”

Fortunately for children and adults today, support for natural hair has also made it to the lawbooks.

The passing of the CROWN Act (Creating a Respectful and Open World for Natural Hair) made it illegal to discriminate against racebased hairstyles in the workplace and public schools.

The bill hasn’t been federally adopted, but several states have picked it up.Among them are California, New York, Oregon, and New Jersey.

Most recently, Massachusets — the home of congresswoman and alopecia advocate Ayanna Pressley (D-MA) — signed the bill into law.

In honor of Alopecia Awareness Month, Pressley recently shared her vision for the future of health for those living with alopecia.

She said on the house floor, “Thankfully, although (alopecia) does not threaten our lives, it does not mean it does not impact it.”

“Collectively, we are fighting for bold investments in skin disease research, comprehensive medical coverage, and meaningful public education to combat the stigma, discrimination, bullying, and indeed even depression and suicide ideation that so many of us experi-

ence,” Pressley said.

She’s currently advocating for wigs to be covered by Medicare for people living with alopecia or undergoing chemotherapy for cancer. When to Seek Out Help for Hair Loss

Alopecia isn’t an experience limited to women or adults.

It can also be caused in ways other than tight hairstyles — such as changes in the immune system, not eating healthy, having a baby, experiencing menopause, and wearing sports helmets.

Peoples-Peterson says there are over-thecounter medicines to treat alopecia, such as the topical cream minoxidil.

Some of the symptoms of alopecia “that could start in the beginning would be itching, tenderness, irritation, breakage,” Peoples-Peterson says.

As a Black doctor, Peoples-Peterson recommends seeking out professionals for advice, like a natural hairstylist for initial advice and a dermatologist before the condition progresses.

“We’re familiar with the types of styling practices that we use on our hair,” she says. “And usually, if they come and get help before scarring has actually occurred, most of the time, you could restore the hair.”