Tending

to Our Garden

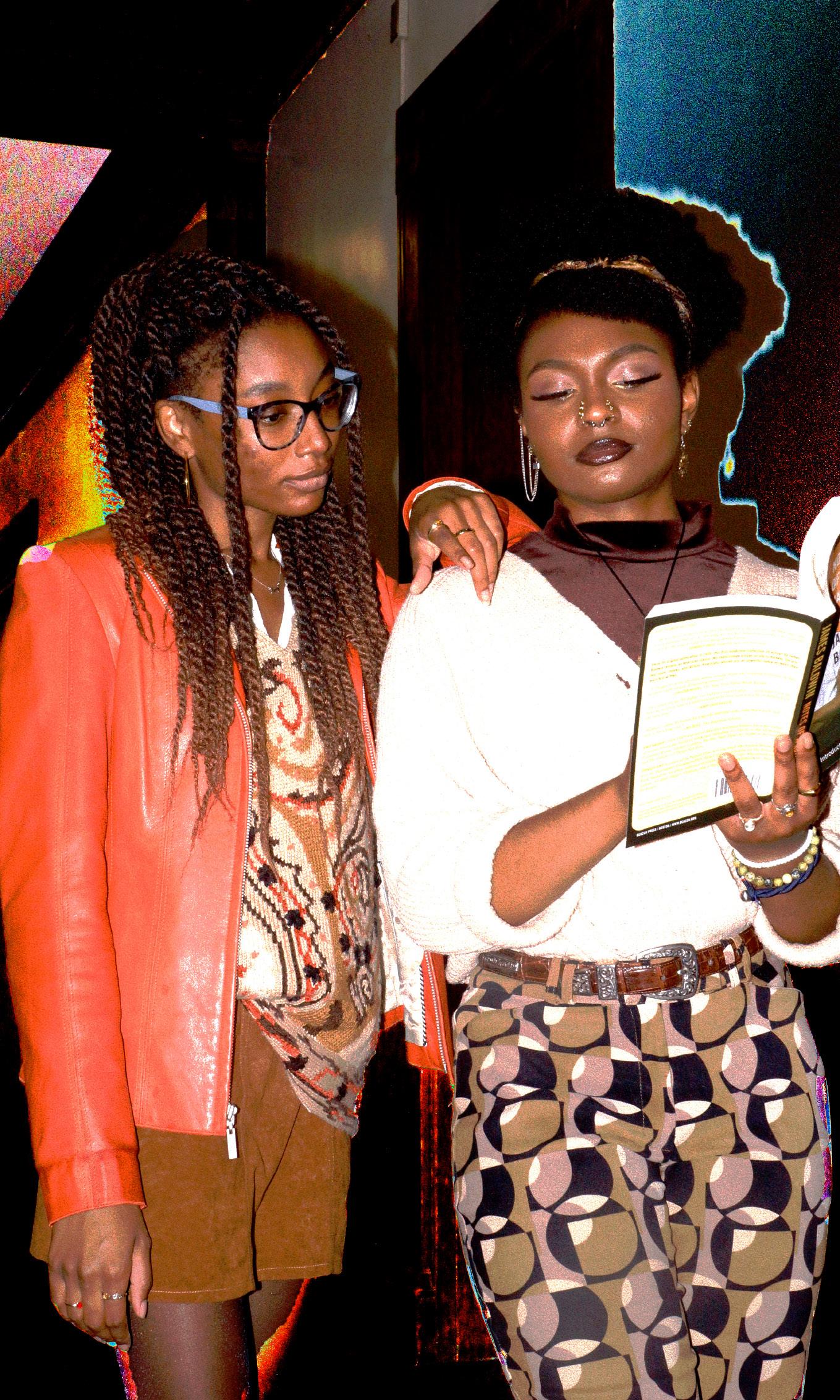

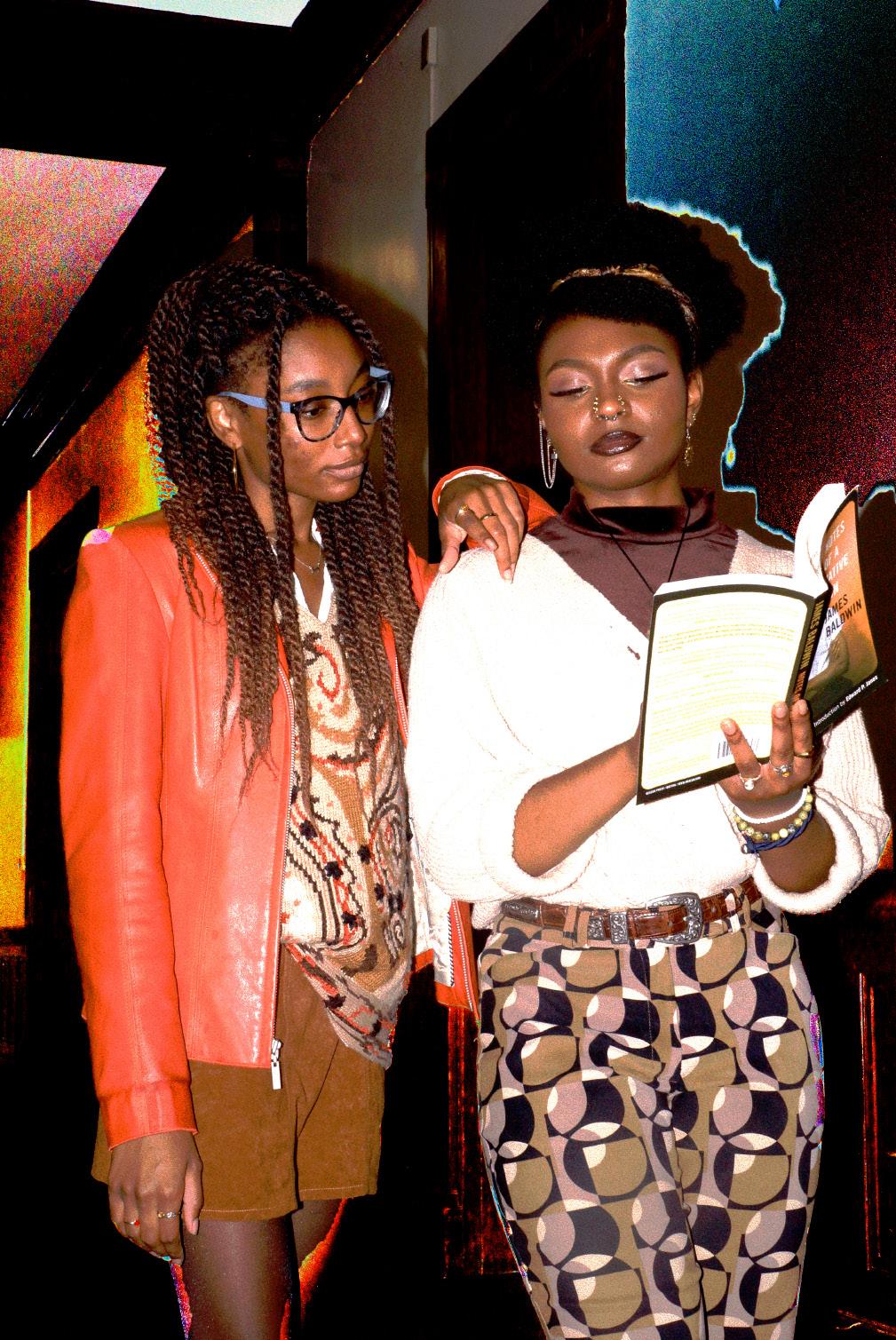

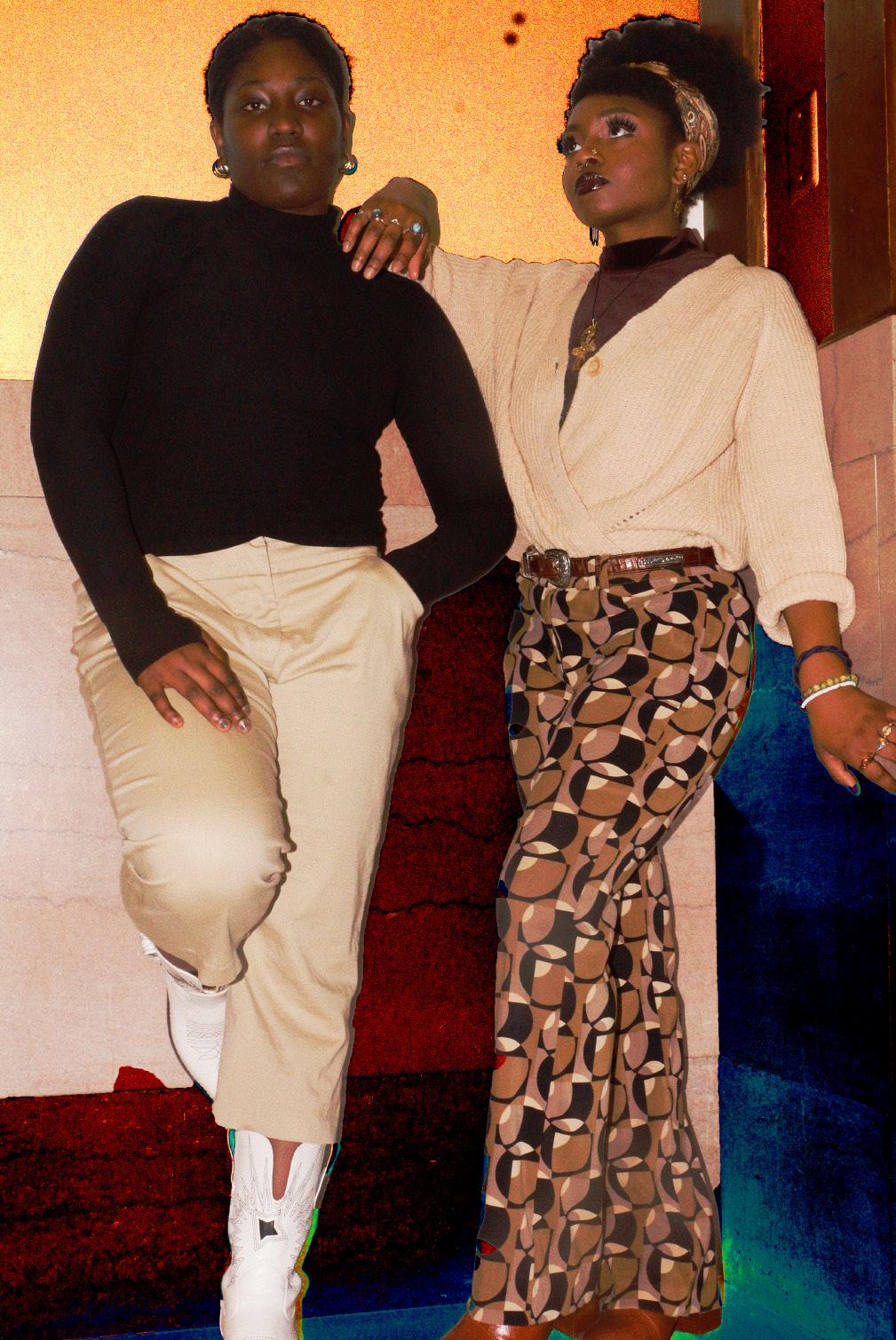

Models Featured: Olivia Olson, Kruttika Gopal, Satreen, Ekua Hudson

Models Featured: Olivia Olson, Kruttika Gopal, Satreen, Ekua Hudson

December 2022

Models Featured: TreVaughn Ellis, John Paul Mejia, Koa Pegram, Chris Herrera

Photos Courtesy of: Alia Abdur-Rahman

Models Featured: TreVaughn Ellis, John Paul Mejia, Koa Pegram, Chris Herrera

Photos Courtesy of: Alia Abdur-Rahman

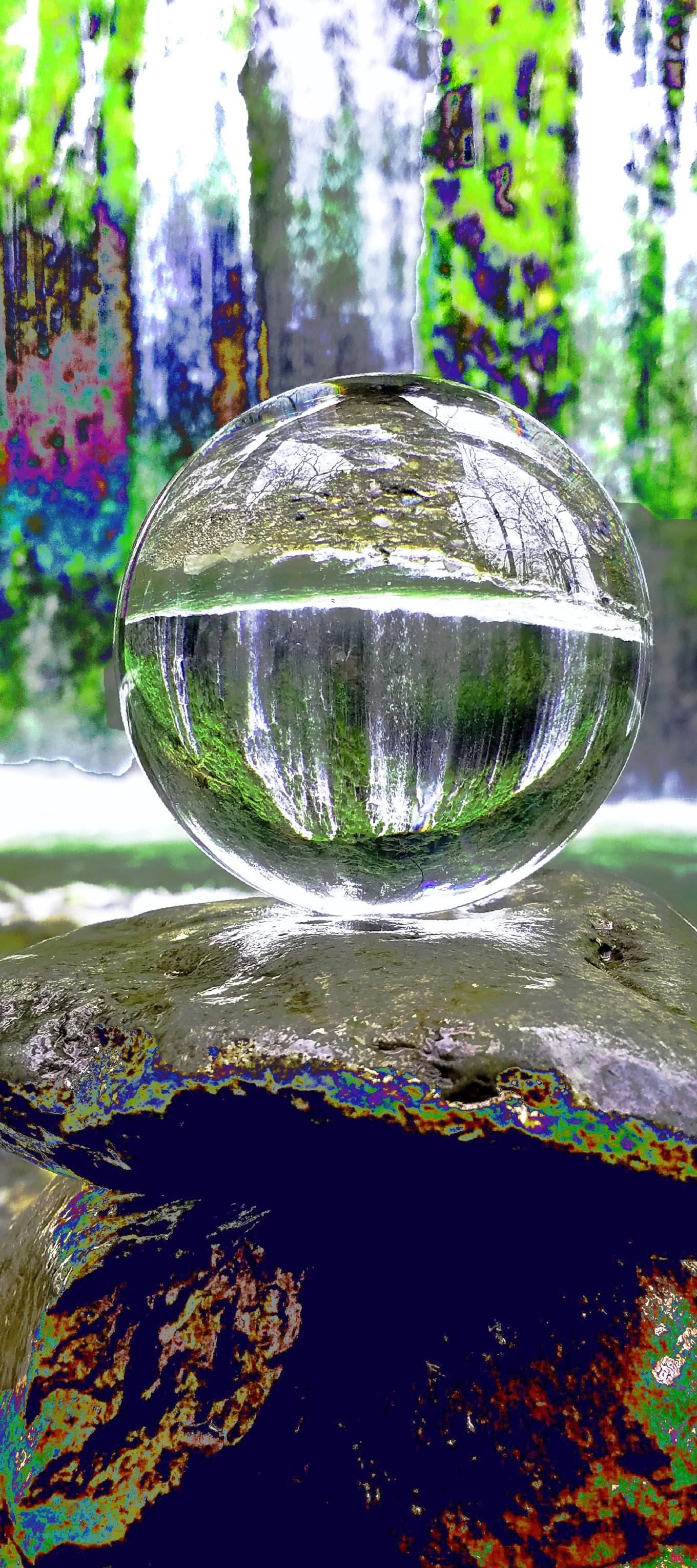

Models Featured: Ehren Layne, Omar Nurr, Rougui Traore

Location: Great Falls Park VA

Models Featured: Ehren Layne, Omar Nurr, Rougui Traore

Location: Great Falls Park VA

Photos Courtesy of: Benjamin Schmida

Photos Courtesy of: Benjamin Schmida

Dean: The Blackprint Co-Editor-inChief 2022

Iwant to begin this farewell and letter to you with a question— what does it mean to tend to a garden, in the metaphorical sense? For me, the creation and cultivation of the Black print embodies the answer to this very question.

We have cultivated and tended to a space in which life gains new meaning, where beautiful ideas can grow, where together, all of our glorious creations have contributed to thoughtful work. Like a garden, we are made up of many moving parts, of many different life forms with unique needs and talents. Each has their own niche, their own appeal, and yet, we are all rooted in a similar soil. The seeds were planted many years ago, by two talented Black women who sought to create a safe space where our people can blossom.

The Blackprint has been my garden on campus for the past three years now, and it has been the very garden where I learned more about myself, my passions, and most importantly, my community. I have been able to tend to the Blackprint’s garden, and have had my talented peers tend to me. We have supported each other in ways that may seem impossible in a world today that constantly must confront turmoil; from racial violence, to pandemics, constant threats to our bodily autonomy, and in the face of an ongoing climate crisis, all of which this magazine issue attempts to connect. Together, the Blackprint family has grown into a community, and I am incredibly thankful to be a part of a space where we can truly flourish and blossom to our full potential. In a world that is constantly trying to rip us from our roots, we continue to survive, and endure the elements thrown our way. We imagine new possibilities, we solidify solidarities, while paying homage to those who came before us.

This 11th magazine issue attempts to do exactly this. By highlighting such voices and amplifying them together in solidarity, we hope to go beyond discussions of representation. Instead, we attempt to showcase how our com munities and allies have always been here, at the forefront of radical care in tandem with Mother Earth. We are actively imagining new possibilities, we are ready to implement new methods of survival, all while calling upon all who walked this planet before us to build radical lineages. We have always cared and tended to each other, in the face of colonial and imperial violence, as we see in the form of climate injustice.

Although my time as co-Editor-in-Chief alongside the brilliant Isaiah Washington is ending as I enter a new chapter in my life, this sacred garden remains eternal, so long as those after me continue to tend to it. The community leaders that are featured on the cover of this magazine alongside our staff members, Section Editors, and Creative Directors who spent hours writing, editing, and creating for this issue are living proof of how this garden continues to grow.

Yours Truly, Jasmine Dean

Dear Reader,

For this semester’s magazine issue, we wanted to centralize the re lationship between people of color and the natural world. Outdoor recreation is perceived as a white expression. The green thumb is always white. This installment of The Blackprint resists those renderings with poetry, photography, journalism, music, and meditations.

Environmental activism buoys many of us at American University, existing as much more than a social media post or essay submitted to Canvas. It is a life’s work. The student leaders we have foregrounded with this issue have all made the environment a site of empowerment. From food sovereignty to land reclamation to sustainability to environmental justice, these members of our AU community have positioned their work to be bulwarks against the shattering effects of climate change and colo nization.

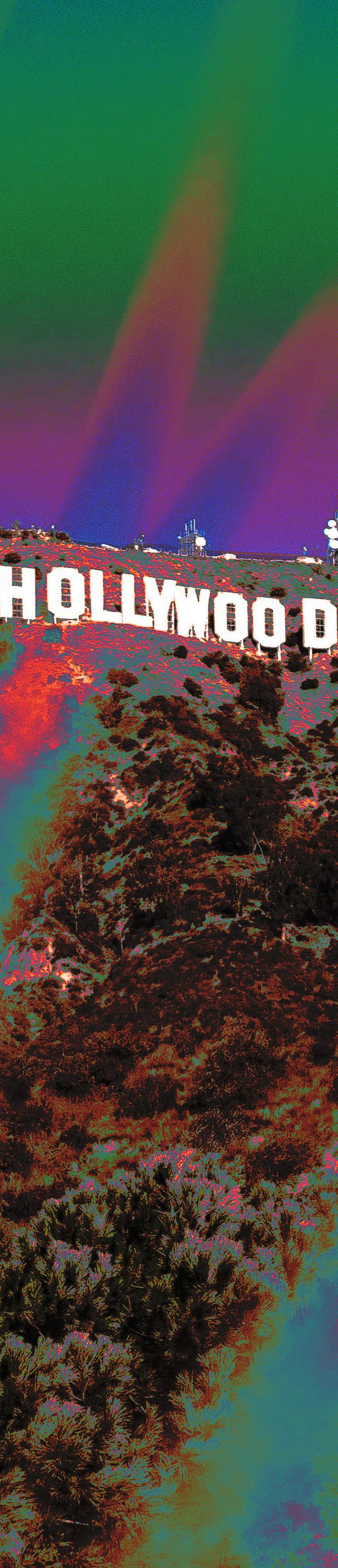

With Meridian Hill Park being renamed after Malcolm X, the loca tion stands at the intersection of the environment and political activism like all of our cover features. With its soil being rich with this context, it just had to be the ground on which our featured activists stood on to get photographed. Nearly all of our photoshoots, in fact, were set outdoors, leaves floating in front of faces and trees backdropping bodies.

Working on this edition reconnected me with my family’s roots and branches. I was taken back to Jamestown, a freedom colony my ancestors established in the Pee Dee region of South Carolina. People formerly without agency found autonomy in tilling the land on their own terms. People treated like cattle were now raising them. Jamestown’s existence born out of resistance is my template for food sovereignty and land recla mation. The vision of Jamestown guided me in helping to create this entry into The Blackprint’s publication history.

I am deeply indebted to all the Editors-in-Chief who came before me who gave us a space to amplify, challenge, and rectify the issues that impact students of color and our communities. Thank you to Jasmine. If carbon dioxide, water, and sunlight are required for a plant’s growth, she is all three to The Blackprint. I will miss her as grass misses rain. She has given so much of herself to this organization and thusly a part of her will always live on with it. I am so grateful for the gifted writers, artists, and

photographers who are the steady, rhythmic heartbeat of this edition. A big thank you to our executive board. Thank you for the meetings, Group Me replies, edits, suggestions, and ideations. I have so much love for our talented staff. Our campus community is full of so much light. We just hope we have managed to refract some of it in this issue.

With gratitude, Isaiah Washington

-Parable of the Sower, Octavia Butler

Isaiah Washington The Blackprint Co-Editor in Chief 2022

“The Destiny of Earthseed is to take root among the stars.”

I remember my first interaction with BP during CultureFest, right outside of Einstein Bagels. I remember being shy and intimidated to introduce myself and ask the E-Board at the time for more information. I remember the first faces I met, the BP logo sticker handed to me that stayed on my computer for three years, and the decision to sign-up for interest.

That was the first time I had made a decision for myself in college, the first time I joined a campus organization. The BlackPrint in many ways was my first engagement with college students outside of academica and I fell in love with it. I loved the mission, the pur pose, the feeling of being able to be expressive, free, critical, and surrounded by likeminded writers with a passion for the Black Diaspora’s promotion of thoughts and voices. I remember the acceptance letter into BP and the first interest meeting and section meeting. I’d never been so excited to be a part of something bigger than myself, something that felt like a community.

I started off as a writer for the Opinion section where I wrote two pieces, one pub lished and one unpublished. The feeling of writing my first piece was invigorating but the feeling of harsh criticism was disappointing yet, even more, the excitement of my first piece being published is a feeling I wish I could feel again. I felt proud and honored. The combi nation of my piece being published and anxiety waiting for it to be published…influenced me to apply for something bigger. The following semester of Spring 2020, I became the As sistant Copy Editor. It was a position that helped me set up for the position that I hold today. But, I hungered to be more active in the organization, more immersed, and more inclusive to writers and topics. I applied to be Copy Editor which has been the best position I’ve ever held throughout my career of campus leadership.

The joy to read, publish, and provide feedback on EVERY article between 2021-2023 for the BP, is my biggest honor. I’ll miss the stress of editing but happiness to publish, the critical feedback I provided but the powerful articles written. As I turn the page forwards to the future of writing, I can’t help but give an ode to the BP’s community and pride, love, cel ebration, and dignity. It’s been a joy. After four years, my time has ended but my words and edits remain present. From writer, to Assistant Copy Editor, to Interm Sports Editor, to Copy Editor my work at BP becomes a chapter almost flipped but those after myself will flourish. The beauty of the leadership I was under and the leader I was are memories and connec tions that will never be forgotten. From writing articles of opinion, to fashion, to sports, to campus/district, to culture; the BP’s legacy remains strong. I have nothing but well wishes towards the success and inheritance of BP, a community, an organization, a group of trail blazers who liberate, acknowledge, and uplift the voices of the AU Black Diaspora, Latin(e), Arab, Asian student body. The lessons I gained are some of the rarest jewels. Thank you to BP, its leadership, and its writers!

It’s hard to say goodbye to the passions you love most. The thought of saying goodbye to a community, a culture, a new found form of expression is something I’ve been preparing myself for since I became a writer during my freshman year.

By Sydney Houston

By Sydney Houston

Many of the Dis ney Live Action films have gone by without causing cultural significance or being over whelmingly remarkable. The biggest buzz was surround ing Beyonce’s involvement in The Lion King and Will Smith playing the incompa rable Genie in Aladdin. But something different is shap ing up to be a cultural reset on May 26th, 2023 the re lease of The Little Mermaid Live Action film, with Halle Bailey playing the title’s Prin cess Ariel.

The teaser, released on September 9th, 2022, was visually stunning. Opening with the crest of a massive wave on the sea, you are immediately taken into the water. The following shots take the viewer through what feels like swimming in the deep sea. The fish look nothing like CGI, and the colorful coral and sea turtles feel like something from a real nature documentary, not a Disney film. Thirty seconds in, we get the shot of the shipwreck, one of the significant settings for the film recognizable to a Disney nerd like myself.

The music begins to pick up as a bioluminescent tail finally swims into the frame. You get quick glimpses of Ariel swimming across the shipwreck through the ocean to the perfect shot of her tail flicking as she enters her treasure cove. And finally, as the trailer begins to close,

we get to the title screen, and hear one of the most iconic Disney ballads, Part of Your World.

In the last thirty seconds of the trailer, we finally see Ariel, with her ginger locs and beautiful voice teasing some of the amazing music we’re going to hear with the stunning visuals that make it look like Halle learned how to deep sea dive for this role.

I felt an immeasurable amount of joy when I watched the trailer for the first time. I have loved swimming since I was a six-year-old learning to tread water. My sister, our neigh borhood friends and I, at the pool would play mermaids and sharks and minnows un til our fingers were pruned. The smell of chlorine is a happy nostalgia, but our family beach trips in the summer were unmatched.

The ocean had always felt like a safe cradle; floating on the waves, pretending I could control them like a water bender, riding through the shallow waters on a boogie board, the water has always been a home for me

Ariel is now a Black girl, giving us a representation that is genuinely never-be fore-seen.

This is not only a cultural reset for Black people who have never been given the opportunity to take owner ship of the water or to be a commonly, beloved prin cess; it also apparently takes something away from white girls. The numerous outcry of many, but predominantly white voices in reaction to seeing Ariel as a Black mer maid tried to dominate the internet. Despite the com mon complaint about her “hair color” and “red-haired representation,” we all know what color was really bother ing them.

I think that seeing TikTok’s of the little Black girl’s in their Princess Ariel nightgowns, watching the trailer, and hearing them say, “she looks like me!” is more memorable than some internet uncle on Facebook crying about what a fictional fish should look like. I will be happy to en dure being in a movie the ater surrounded by kids next May because we’re all feeling the same thing: seen.

So many young, Black girls have played mermaids, but the only princess who looks like us was

a frog for 23 minutes, more than half of her screen time.

Ekua Hudson is a junior at American University studying public health on the pre-med track. Hudson is a Frederick Douglass Distinguished Scholar and the president of the Food for Thought Foundation.

The Food for Thought Foundation is a 501c3 nonprofit committed to ending food deserts by changing the way that food is supplied, predominantly serving DC’s wards seven and eight.

The Blackprint: Can you tell me a bit about yourself?

Ekua Hudson: Hi, I’m Ekua. I’m 20 years old and I am the founder of the Food for Thought Foundation. I’m an introvert. I like really good independent films about people, like people movies. And I really like to read books and I like to bake.

BP: Where did you grow up, and how do you think your upbringing influenced your personal and academic interests?

EH: I grew up most of my life in Florida and Spent like a fourth of my life in Ghana, so about three months out of a year. My dad is an organic farmer. So growing up I was always on the farm with him. I would watch him plant stuff, watch food grow and that definitely impacted me. My mom is also an engineer, so she would take me to work sometimes and I would see what she does. But mostly it was seeing how food is grown and production of food. Seeing how food systems are different in different countries made me start to think about how in Ghana, you can get more organic food than you can here because the food supply is differ ent.

Growing up Black, I was always taught to place my value into the church: into the Lord’s hands. The idea of witchcraft, Voodoo, and Hoodoo, were all touchy subjects in conversation amongst BlackHouseholds, including mine and others I visited. Discussing the devil was perhaps one of the one ways I could get my mother to stay quiet. Whenever I tell Black people I don’t align with Christianity, they automati cally assume that it’s a phase or they see me as someone different, because the Church plays such a strong role in Black culture. But what failed to be connected in conver sations was that my identity in spirituality is also connected to Black and African culture.

With the release of the Princess and the Frog, Voodoo and African spirituality gained a negative view in American media, because it easily became associated with evil. The film introduces the infamous “Voodoo Queen”, Mama Odie, as an intimidating character, for her to only end up being a kind, older lady with strong connections to both environment (as in nature and animals) and spirituality. More well known, the villain of the story, Dr. Facilier, also known as “the Shadow Man,” tainted the media’s associations to Voodoo. Considering the connotations tied with his character as a villain, he was also shortcutted to receive the name “the Voodoo Man” in the media (not directly through Disney), which overtook the popularity of referring to the character by his actual name. This addition of this new name ended up tagging on a more pronounced negative connotation onto African spirituality, specifically Voodoo and Hoodoo.

However, in 2020, there began a rise of white spirituality, which stole aspects of spiritual ity from different cultural contexts, namely Indigenous to the Americas, African, and Asian contexts across diasporas, consuming such practices into something that can benefit the white dollar.

By: Madison Jackson

TikTok, where white “tarot readers” would extract a basic, and usually positive, message from the cards following the lines of “love is coming into your life” or “you will receive life-changing news within 48 hours.” White content creators began embracing white spirituality by embracing hikes or walks to connect with the environment, while it is still deemed suspicious for a person of color to be alone in the woods.

With the rise of white spirituality, more white-owned and operated companies have begun selling crystals, either made from the real crystal or plastic to appeal to the bandwagon of spirituality that began to take hold in the start of the pandemic. Some platforms that sell their crystals promise ethical sourcing but fail to men tion the specifics. Mining for crystals doesn’t have the same impact on the environment as gold, but with the rise of popularity for crystals and interest in spirituality, there comes a rise in the need for more crystals to be supplied.

There has also begun a spike in cultural appro priation in relation to spirituality. Whether it be waist beads which, originated in Africa and represent femininity, fertility, and spirituality, or Bindis that can represent marriage and are a part of Buddhist and Hindu culture, the open of the so-called gateway to ‘White Spirituality’ created unsolicited welcomes for people to tag along onto cultures they aren’t a part of.

While an appreciation of cultures is good, there has also been a violation of the closed practices some cultures have and appropriation has become more common. On TikTok, it is common to see witchcraft spells shared, but brujeria and santería have also gone viral and practiced by non- Latine/ Afro-Caribbean people. The most well known spell was a binding spell, where a person would draw a cross on their younger with honey, to keep someone (usually a crush/ partner) in their life. Although it is not as common as brujeria and santeria, Hoodoo practices have also gained some interest in the media even though it is closed practice as it was created by enslaved Africans who would use the materials around them, nature or man-made objects, to practice their work.

Aside from rituals and spellwork, being in na ture is key to a lot of grounding, outside from shadow work (self-reflection), because it allows people to seek their answers from sources outside of another person. Nature provides solitude and clarity whether it be from beachy waves or from the fall leaves at the amphitheater. The fear that comes from not feeling safe alone in nature makes grounding difficult.

Whether it’s the fear of being mocked for basking in the sun alone or the fear of being watched or taken when alone, being a person of color and interested in nature, whether it be for the sake of loving nature or to heal, it does have its constraints.

Keeping the failed government response to Hurri cane Maria in mind, ongoing crises of poor energy policy and crumbling infrastructure remains clear as Puerto Rico was ravaged by Hurricane Fiona, ex periencing week-long power blackouts.

For context purposes, Puerto Rico’s power grid is managed not by the state— but by a private company Luma Energy, which has managed the island’s power grid since summer of 2021. As a relic of colonial ism, Puerto Rico is dependent on the United States government, specifically the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), to coordinate disaster relief initiatives and approve funds for storm dam age and infrastructure repairs.

After Hurricane Fiona battered the island, the en tire power grid collapsed leaving millions of Puerto Ricans without electricity for weeks. Similar to the aftermath of Hurricane Maria in 2017, many Bo ricuas were without basic necessities like running water, power, and a reliable supply of food. Especial ly, given the Trump Administration’s apathetic re sponse— as the former President threw toilet paper at an assembled crowd, Trump’s general incompe tence culminating in his assessment that disaster relief is hard because “it’s an island surrounded by water” showing his administration had no plan to alleviate Hurricane Maria’s damage on the people of Puerto Rico.

Notably, the Puerto Rican territorial government failed to report an increased death toll that even tually peaked at 3,025 showing the consequences of poor public leadership at the local and national levels.With the failed response to Hurricane Maria in mind, the Biden Administration’s response to Hurri cane Fiona was far more effective and incumbent of the Office of the President. Immediately addressing the nation, President Biden issued an executive or

der declaring Hurricane Fiona an “major emergency”. After Biden’s prompt declaration, the commander in chief personally visited Puerto Rico and reaffirmed his support for the Puerto Rican people. However, months prior, unlike Biden’s congeniality towards Puerto Rico, the Supreme Court in 8-1 decision over turned certain federal benefits for Puerto Rican vet erans seeking benefits for disability and other condi tions.

In her lone forceful dissent with the majority opinion, the Court’s first and only Puerto Rican member, Jus tice Sonia Sotomayor, condemned the Court’s find ing equating it to the ca second class citizenship and calling for reversal of the Insular cases which were early 20th century Supreme Court cases that originally determined Puerto Rico’s political status and sover eignty as a U.S. territory and initially deprived Puerto Ricans of US citizenship. Though Biden swiftly responded to Hurricane Fiona, Puerto Rico’s inherently racist colonial status and en during issue of hurricanes and tropical storms jeopar dizes its residents’ lives, rights, and incorporation in the greater scheme of American society.

As I reflect on Hurricane Fiona and Maria’s deadly and catastrophic toll on Puerto Rico, I remain hopeful for the island given its incredible and resilient people, but question the strength of its infrastructure.

When I first saw the film “Moonlight,” its “Middle of the World” scene where a young Black boy named Chiron learns how to swim particularly struck me. I immediately thought of my cousin who drowned on a school field trip. His story became a cautionary tale of what happens when Black bodies wade beyond the shallow end.

the birthplace of wade-ins, I witnessed the “whites only” sign dangling now only in metaphor on the entrances to beaches and pools getting removed. I witnessed the ocean getting demilitarized. I witnessed the water getting reconceptualized as a place of serenity for the Black body once and for all.

instructed from a young age

I

like the rest of

country, whiteness exclusively owned the pools

waterways.

birth-

The director of “Moonlight” Barry Jenkins said that the actor who played young Chi ron, or Little, did not know how to swim himself and was learning how to during filming, making the moment all the more powerful as the audience bobs up and down in the water like Chiron via the camera’s horizon place ment.

“Black Panther: Wakanda Forever” similarly makes wa ter an indispensable motif. Many of its actors too pos sessed little swimming abil ity prior to filming. Tenoch Huerta who brings Namor the Sub-Mariner to life re torted “I’ve never drowned before” when director Ryan Coogler asked if he could swim. Angela Bassett’s an swer to him was “a little bit.” “Black girls have this history with water and their hair,” Bassett said in an interview with Variety. Coogler learned how to swim himself in or der to join the actors in the water.

As Chiron made a home out of Miami’s crystal waters,

Danai Gurira, who plays the General of the Dora Milaje Okoye, was a competitive swimmer when she was

was

that

the

and the

And if I were to go to a friend’s

day pool party or go past the lowest level foot marking on the hotel swimming pool or go on the field trip to the water park or to the pond behind the middle school, I would be crossing the color line into a world my family could not save me from if I lost my footing.

younger. “I found out that Black kids are five times more likely to drown than white kids,” she said. Com mitted to altering that reali ty, Gurira told Entertainment Weekly, “I want to see more and more Black kids learn how to swim.”

It is true that 64% of Black American children can not swim. A study conducted by the USA Swimming Foun dation and the University of Memphis found that there is a strong correlation between Black Americans’ lower participation in swimming activities and the higher rates of drowning among Black youth. The 2017 study concluded that Black Ameri can children were less likely to have family members or friends who knew how to swim or were excited to swim. A fear of drowning appeared to be racialized in a study published in the Journal of Black Studies with the fear being more para lyzing for Black caregivers and providers than for their white counterparts. Swim ming inability then becomes an heirloom for many Black American families.

Genesis Holmes was a 13-year-old Black boy from South Carolina who drowned in a pond like my cousin. His mother Jennifer Holmes said in an interview with AJ+, “All of our life, most of us, honestly, we was told to stay away from the water. It’s like a family tradition that they had from generation to the

next generation. So, I taught my children to stay away from water.” Inspired to dismantle perennial notions on water held by the Black community, she opened up the town’s first public pool, naming it after her son.

Marvin Thorpe II, the Di rector of the 4M Swim Club, is the son of the founder of the program who started giving swim lessons in his backyard pool in Windsor Mill, Maryland in the sum mer of 1972 following his son’s near death in that same pool. The duo taught over 20,000 students over 48 years before the father’s passing. In my interview with the son, he shared that what casts over the formation of a Black aquatic heritage are “shadows of segregation.” He states that only 3 out of the 40 teams in Baltimore fea ture people of color, viewing representation as indispens able to his work.

He recalls swimming at the North Baltimore Aquat ic Club where swimming superstar Michael Phelps trained and being one out of three Black people there over the span of six months. He said he felt like Ralph El lison’s “Invisible Man” when he trained and competed in these uber-white spaces. Serving as the instructor to many Chirons and producing his center’s own Olympic hopeful, Thorpe said, “If you are the only Black student in a class, you keep with it because you are trying to

complete your degree, but the white cold shoulder is completely unacceptable when you are learning how to swim. It’s different than sitting at a desk, you could die.”

“Swimming is the only sport that can save your life,” Thor pe said.

Only four public high schools in Baltimore have a working pool and swimming team.

The Chick Webb pool, the first indoor swimming pool in Baltimore’s Black community, was earmarked for demolition with Black legislators pushing instead for its renovation.

Financing is an issue with an Urban Institute report find ing that African American Baltimore neighborhoods were far less likely to receive investment than predomi nantly white ones. Baltimore is not alone in experiencing pool closures with more than 1,800 public pools used by Black and Brown communi ties disappearing since 2009 according to AJ+.

Doris Minor-Terrell, East Baltimore resident and presi dent of the Rutland Lafayette Community Association, described to me young Black children from Baltimore, “little people” as she called

them, who perished at beaches during family va cations with them not being able to swim due to limited water access. “Children are naturally attracted to the water,” she said, “Thus swim ming should be a priority. It means survival. We teach them how to look both ways before crossing the street. Learning how to swim is just another means of survival, it’s a seatbelt.”

Marvin Thorpe II believes depictions of a positive association between water and Black people in movies and television can aid in his effort to fulfill his father’s dream “of a day where there are no reports of a child drowning.” He recalls seeing a commercial where a Black man was swimming and how it moves him to this day. There is a liberatory func tion then latent in Jenkins’ “Moonlight” and Coogler’s “Black Panther: Wakanda Forever.” These films are representational interven tions key to cobbling togeth er a radical reality where all Black adolescents are cap tains of their fate because they have learned how to be warriors of the water.

While natural disasters do not discriminate, the long-term impact dispropor tionately falls on low-income minority communities. Toxic sites in proximity to Black, brown and Indigenous com munities in the United States disproportionately affect them in tandem with socio economic inequalities. The climate disparities within the United States have become increasingly homogenous towards the resources and funding in terms of distribu tion. Hurricane Katrina was one of many examples in dis playing to the American pub lic the federal government’s grossly indifferent response to the plight of low-income, Black American communi ties. It displayed how pover ty, economic inequality and racial injustice impact the delivery of disaster relief.

There’s a trend of predom inantly Black, brown and Indigenous countries and communities as we have seen in Florida, Houston, Puerto Rico, Cuba, and Haiti that receive a tremendously low amount of aid after hur ricanes, earthquakes or any other natural disaster. The low provisions of safe water, electricity, food and medical care after disaster to timely rebuild communities con tributes towards the neglect and the financial hardships. Financial insecurity is anoth er causation for why people can’t safely evacuate, or gain access to housing and food. The racially and economical

ly segregated communities are predisposed to higher health concerns and over flooding from toxic waste sites. These are not coinci dences. Environmental rac ism and prejudice pre-dates to the beginning of slavery which has extended itself into the present through seg regation and redlining.

Here Are 9

Disproportionate Impacts: *several of these facts are cited and taken in reference to the Center of American Progress and Princeton Uni versity*

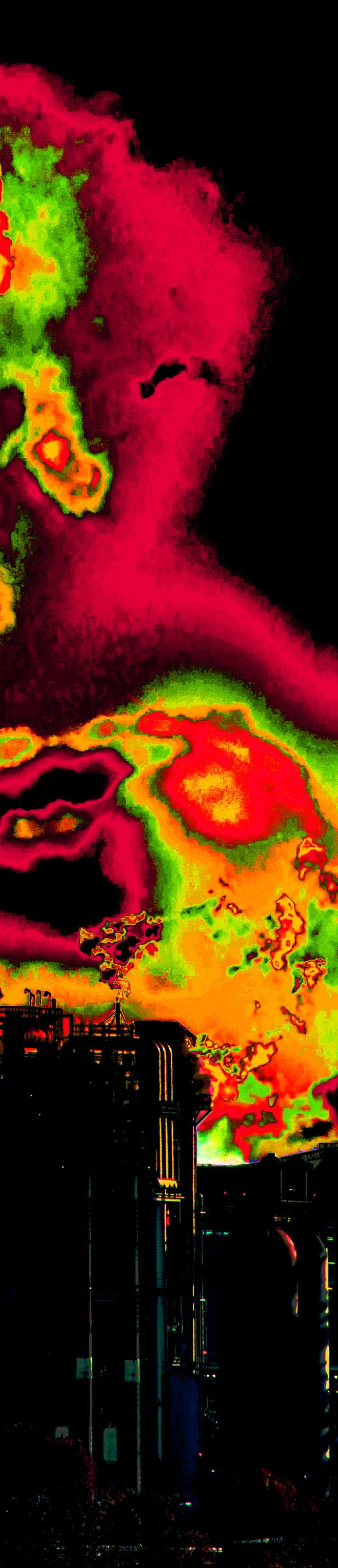

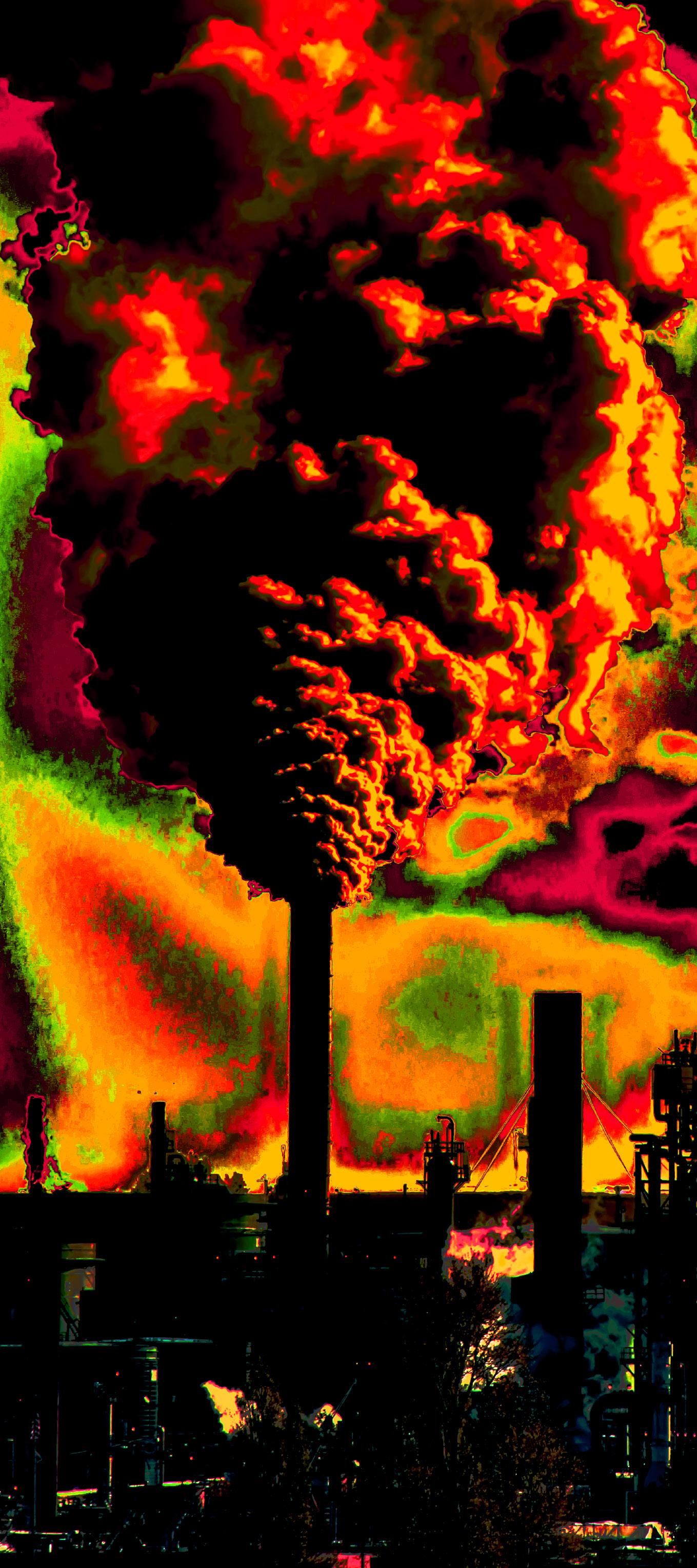

Displacement through the means of gentrification. The decade-long action of white people renovating and moving into Black and other minority communities has contributed to the negative impacts of displacing Black people into low-income envi ronments with heavy polic ing, poor ecological biodiver sity, leaving many to become predisposed to detrimental health conditions.

Companies relocate in proximity to Black and Indigenous communities. The commonality of reloca tion into Black and Indige nous communities or even the placement of toxic waste sites, companies, and pipe lines through the lands seep dangerous chemicals and air pollutants. This has affected the conditions and aftermath of spillages during natural disasters predisposing Black, Indigenuous, and minority

communities to hazardous environments.

Black and Indigneous communities have higher exposure rates to air pollution than their white, non-Hispanic counterparts. African-Americans have higher exposure rates than whites for 13 out of the 14 pollutants. Some of the pollutants studied have been connected to asthma, cardiovascular issues, lung disease, and cancer. For example, a case study of The Bronx, New York, found that individuals who lived close to noxious industrial facil ities and waste sites were 66 percent more likely to be hospitalized for asthma. Significantly, these same individuals were 13 percent more likely to be people of color.

Landfills, hazardous waste sites, and other industrial fa cilities are most often locat ed in Black and Indigenous communities.

Over a twenty-year period, more than half of the people who live within 1.86 miles of toxic waste facilities in the United States are people of color. A report by the Center for Effective Government

By: Amaris Levitt

By: Amaris Levitt

found that people of color are nearly twice as likely as white residents to live within a fence line zone of an indus trial facility.

Water contamination plagues low-income areas and communities of color across the nation. There is limited access to clean water in low-income communities of color by design. Water contamination has largely affected children of color who live in rural areas, indigenous communi ties, and migrant farmwork er communities. Contam inated water can cause an abundance of health-related issues, particularly for young children. Depending on the contaminant, possible health problems can include water borne diseases, blood disorders, and cancer. Indigenous people of the Navajo Nation, for exam ple, have suffered for years from water contamination due in part to the residual effects of urani um mining in the region during the 1950s, as well as the recent Gold King Mine toxic spill. In St. Joseph, Louisiana, residents are forced to live on water that is tinted brown and yellow but that the state continues to claim is safe to drink. African-Ameri cans make up three-quarters of the town’s population and nearly 40 percent of the residents live in poverty.

Air pollution in the United States is another example of environmental racism. For example, more than one million African Americans live within a

half-mile of natural gas facilities, over one million African Amer icans face a “cancer risk above EPA’s level of concern” due to unclean air, and more than 6.7 million African Americans live in the 91 US counties with oil refineries. In total, African Americans are 75% more likely than White people to live in “fence-line” communities (areas near commercial facilities that produce noise, odor, traffic, or emissions that directly affect the population).

Ocean acidification occurs when the natural pH of ocean water is lowered due to in creased CO2 levels. The ocean absorbs about 30% of CO2 released into the atmosphere. These molecules then undergo a series of chemical reactions that release a surplus of hydrogen ions, which lowers the pH of the water. These risks are am plified in communities such as coastal Native American tribes, whose diet and economy rely on seafood.

Coal plants are large emitters of mercury, lead, sulfur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide, and carbon dioxide – a potent greenhouse gas. Along with contributing to climate change, pollution from coal plants is linked to asthma attacks, heart problems…all 378 coal-fired power plants in the United States according to a plant’s impact on the health, economics and environment of nearby communities. Peo ple living near coal plants are disproportionately poor and minorities, the report found; the six million people living within

three miles of those 378 plants have an average per capita in come of $18,400 per year; 39 percent are people of color.

Green America stated “...Black or Latino, you’re more like ly to live near toxic facilities, like petrochemical companies here in Louisiana, producing toxins that shorten and impact quality of life. And then, [our communities] are on the front line of impacts from climate change, living in places where there could be more floods and a higher incidence of different [climate-related] diseases. For poor communities, there’s also not having access to health in surance or medical services.”

How Can We Advocate? Our advocacy as a community begins with our voice, our resistance, and our push for better conditions.

Advocacy includes support ing other minority communities under similar oppression and conditions as well. Our voices between our local leaders, our actions begin with voting. We have done more than enough crying, yelling, and shouting yet they still don’t want to hear or see us. But, by using the right that was once denied to us, by sending the proper leaders in the House and/or the Senate, by speaking to legislators to aid in passing the proper bills, by engaging our communities in programs pro vided by FEMA, and by shaking the ground with our voice; we can tighten the reins of op pression and slowly eliminate the disproportionate impacts and neglect. The truth is, there should be a better solution, there shouldn’t be a struggle to gain the basic necessities to rebuild our communities, there shouldn’t be a neglect for Amer ica’s people, and there shouldn’t be an outcry to survive. This burden should never be put on the backs of communities that need help, this burden must be put on the shoulders of Amer ica.

*several of these facts throughout the article are cited and taken in reference to the Center of American Progress and Princeton University

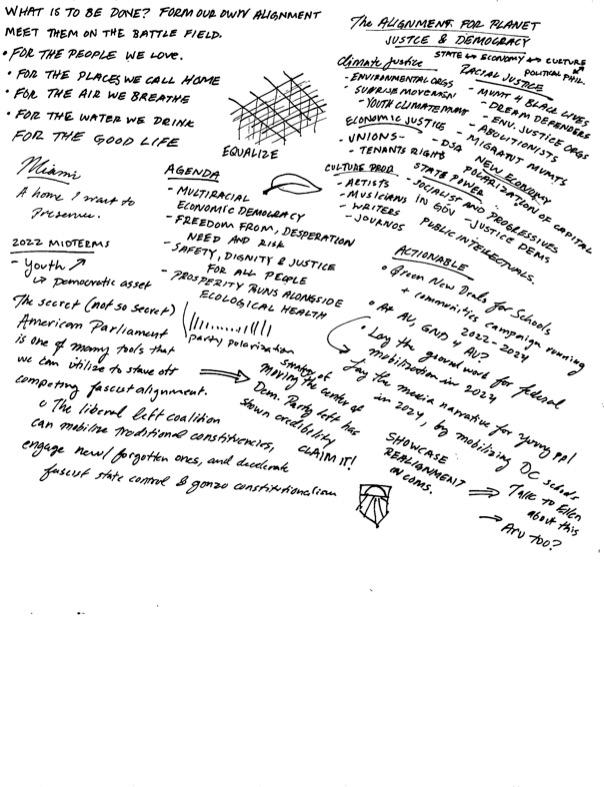

Black, Brown, and Indigenous people have to be subjugated to climate crisis for centuries from their exposure to colonization, slavery, and man-made machinery.

The power imbalances have constrained minority communities to respond to the impact of climate change by building political and economic power critical to the components of climate resilience. An expansion of conversation around climate justice and advocacy needs to be brought to the forefront of the American public, as the lack of this is the true lack of democracy.

It can be seen in many different forms and many of these directly affect health. Air quality is consistently poor in heavily Black-populated areas, D.C. being a strong example of this, and as air quality worsens, asthma among Black children rises. Accord ing to the EPA, Black children experience asthma at two times the rate of White chil dren as well as being two times as likely to be hospitalized for asthma, and four times as likely to die from asthma as White children. The question is why? To help answer this I decided to look out to our backyard, Wash ington D.C.

Taking a closer look at D.C: I first looked at three factors: asthma rates, the racial makeup of a geographic location, and the quality of air. According to the DC Asthma Coalition, 1 in 6 D.C. residents have asthma. D.C. also suffers from high ozone levels that exceed government standards. And according to the U.S Census Bureau, D.C has a population make-up of 45.8% Black, 4.5% Asian, and 11.5% Hispanic or Latino. After looking at these facts it was no surprise that statistics also show that hospitalization rates for asthma in D.C were higher than others.

Trees are a form of nature’s medicine so next, I decided to look at access to parks and hiking trails. As students of American Uni versity, we live with a privilege that, unfor tunately, many D.C. residents don’t get. That being trees. We reside on a campus with an abundance of trees yet there are neighbor hoods in this same city that don’t have a local park within walking distance. This drastical ly contributes to the asthmatic rates within this city and further environmental health disparities.

This large disparity directly affects the health of Ward 8 residents. Ward 8 was hit incredibly hard by Covid-19 and had the highest death rates among all wards in D.C. Although multiple disparities contributed to these numbers, a lack of quality air was definitely one of them. In 2020, DC coun cilmember Trayon White Sr. was interviewed by The Washington Post and was asked for his comments on the health disparities among Ward 8 regarding Covid-19: “ ‘We’ve been suffering from people dying in Ward 8 for the last 30, 40 years,’ he fumed, listing the reasons: diabetes, high blood pressure, asth ma, suicide, homicide. ‘It’s always people of color dying in the city. It’s not nothing new.’ ” It’s no secret that asthma disproportionately affects low-income people of color but we cannot keep letting this problem persist.

When the pandemic began, people were advised to spend time out in the fresh air at parks or hiking since everything else was closed, but what were people living in areas like Ward 8 supposed to do? Environmen tal health is public health and to better the health of the population, we must also better the environment for all, not just those in the right zip codes. Investing in public parks and the creation of green spaces in low-income POC-populated areas is key to breaking down systemic environmental racism.

Environmental racism is defined as disproportionate burdens of environmental risks and disparities among persons of color.

In Ward 3, where American University is, there is an 83.5% white population and over 55 parks as well as a large portion of Rock Creek Park which has 36 miles of hiking trails. But in Ward 8 with a 3.8% White population and an 89% Black population, there are only 1.5 miles of hiking trails and 14 parks.

This is dedicated to all the Black Vegan Unicorns.

I would never have thought my younger sister was anything but confident in herself and who she was; she has always been bold, brazen, and unafraid to let you know her opinion. But when she let me proofread her narrative essay for her non-fiction writing assign ment, I found out that she thought herself pathetic. Pathetic was the last word I would have thought to use when thinking of her.

This feeling of hers came from a holiday that had always been full of joy and togetherness: Thanksgiv ing. She wrote her narrative essay about her first Thanksgiving since she became vegan, where she felt pathetic because of what was on her plate, and the lack of commu nion that she normally shared with our family at the table.

There isn’t a whole lot that I knew about veganism before my sister came home from her college cam pus one weekend, telling my fam ily that she was no longer eating animals. I hadn’t even realized how many by-products in our meals were animal products that she couldn’t eat. As the family food or derer, she made my job a step more difficult. I had to start modifying her order to make sure there wasn’t any meat, that was easy. Or eggs,

By Sydney Houston

By Sydney Houston

still not bad, or cheese—damn, they put that on everything! Or have any milk in it. But wait, what if there are no substitutes? I hadn’t realized that most of the restau rants where we ate didn’t even have completely vegan options, only vegetarian menus一why is cheese on literally everything!

Despite the mainstream popularity and promotion of vegan diets, that community felt very removed from our reality. I thought it was, by and large, filled with people who have better access to organic markets, grocery stores with fresh produce, and fancy salad places with green juice drinks that don’t charge less than $14 for a bowl. All of which are largely absent from Black com munities.

Being Black and vegan is hard for many reasons, but food access and stigma are a large reason for it. 17% of Maryland’s total food inse cure population is concentrated in Prince George’s County. This food insecurity affects normal diets, not even considering providing enough options for someone to choose to be plant-based. Living in Prince George’s County was never a hard ship until our grocery store trips meant leaving to go into Howard County for the Wegmans in Colum bia so my sister could get groceries that supported her diet. But, 8% of Black Americans identify as strict vegan or vegetarian. This is actu ally higher than the only 3% of all Americans with plant-based diets.

Black vegans really came into the spotlight when Tabitha Brown went viral on TikTok, showing that not only was being vegan a normal thing, but that the food did not look or taste bland. Black vegan

restaurants all over the country showcase amazing menus, and inclusive eating options with innovative meat substitutes but, most importantly: seasoning. The truth is that being vegan and Black doesn’t mean losing any of the amazing flavors of our culture. It just means modifying them to be mindful of our bodies and the planet.

Black veganism is actually a political movement. It’s a philosophy and form of social justice activism, coined by Syl Ko and Aph Ko, the creators of Black Vegans Rock.

There are resources and databas es of blogs, featured spotlights of Black farmers, as well as guides all available to start your journey into becoming vegan. The Black Vegan Company’s slogan is “Saving lives. Starting with food.”

I’m hoping that this year my sister can feel a bit better about Thanks giving. I’ve mastered ordering her food and double-checking that there’s no parmesan cheese. We started shopping at Trader Joe’s, which has more ready-made vegan options, and her vegan chili is just as good as the old version with beef. It’s a big change that I’m not brave enough to make, but I’m really proud of her for doing something not only for her body but for making me think differently about ways for the soul to feed us.

So when I started middle school, and definitely coming into high school, I was really inter ested in food because I started gardening on my own and with my mom. But definitely when I got to college, there were a lot of research opportunities, and I was doing a lot of commu nity service surrounding food. I was like, ‘Okay, this is what I’m interested in and I want to do public health.’

BP:

What made you want to work towards addressing this inequity over other pressing issues facing your community?

It’s definitely because of my family. My great grandma had 15 children, and almost every single one of them, including my grandma, has some kind of nutrient based health issue. Either type two diabetes or cardiovascular disease hypertension, autoimmune diseases triggered by diet or even things that you don’t necessarily think are connected to diet like Dementia and Alzheimer’s, things from eating processed sugar. This is why I care about food insecurity so much. Food directly correlates to a lot of the health issues that I see in my life and in my family. I mean, Black people have a lower life expectancy on average than white people. When you like, look at the basic things that everybody needs, food is one of them. So obviously, if you’re not getting the right nutrients, like that’s a really big problem. There are definitely other factors that we should care about in the black community, but I think that the reason why I care about this so much is because I see people personally affected by it. And I think that it’s really pressing because it’s food!

BP:

How did you take action to be a part of reducing food insecurity in your community?

In Orlando at school, I had started building gardens because we were donating to the food bank, and that’s how I first started getting involved in Orlando.

But when I really started getting involved in advocacy work and connecting, not just going through like other businesses, was when we had this project, my freshman year of college and we were online. The pandemic was happening and Thanksgiving was around the cor ner. And I was like, “Okay, the food bank is not going to cut it.”

So I started just talking to people in the community, and I was like, “what do you need?” They’re like “groceries.” So I went to Walmart and I had raised money by sending out letters and I raised about $3,200. We just spent all that money on groceries. [We] bought vegetables, milk, lettuce, not turkeys because that was a little too expensive, but things that you want for Thanksgiving dinner and stuff to make sides and everything like that. We just set up a table and started giving it out for free.

I think when I really got involved in the structural food insecurity part of that was when I was at that grocery drive, and people were coming by in their cars, and I was just asking them about “how’s your life like, what’s going on?” And people started telling me their strug gles.

So after that grocery drive was when I started talking to my advisor at the time. I was like, “Okay, I want to do this, but also I don’t have the resources as one person to keep raising money to buy groceries every week.” That was a lot of money and it took me like a long time to get that much money, so she said I should start a nonprofit. So I did, with the help of our vice president Sarah and treasurer Kian. From there, it was easier to fundraise because we were a nonprofit and we started doing this program called Sponsorship, where we had to take applications because obviously we couldn’t sponsor everybody, but we put it on the news. And then it was just like if you need groceries, fill out a quick application. It was just like it wasn’t even fast food or anything. It was just to tell us a little bit about what you need, how many people are in your family, and we’ll try to meet your needs and then we just start ed delivering the groceries. And that’s how I really got involved in food insecurity in Orlando was really just through matching people with food work.

BP: What was starting the nonprofit like?

EH:

It was hard. When I came to DC, I knew DC is not like Orlando because Orlando is really spread apart. So if there’s no grocery store in your area, it means there’s no grocery store for like five, six miles. That’s terrible! But when I came to DC I didn’t really understand how there’s a food desert and this was ignorant because I was coming from a place that doesn’t have public transport. I didn’t understand how this food desert is here because you can take the bus everywhere. Until one day I got on the bus and I tried to go to Walmart when I was in school and the Walmart was a two hour bus ride and a train ride away and I was like, “Damn, how am I gonna carry all my groceries all the way back here?” and Uber is expen sive and even once you get to the grocery store, it’s so expensive here.

So then I started interviewing people in communities and I talked to a bunch of people who were trying to make solutions to food insecurity. The first person I talked to was Diwan Mason and she runs this little grocery store food truck. They stock it with fresh produce and they drive it around wards seven and eight. When I asked to interview her, she said, “We have SNAP, we have EBT, but we’re just a mobile grocery store. You can’t get everything that you need from a food truck.” You can’t get tampons and things like that, too. She also said that the cost of rent is just too high. Because people are low income, you have to sell it for a lower price, so the prices Whole Foods sells for, you would never be able to sell for that in wards seven or eight. It’s just not realistic. So I started asking people at companies and non profits and the solutions being proposed were to put healthy food in corner stores and that’s what a lot of people are doing right now.

What I really wanted to know was why is food in grocery stores so expensive? The answer to that is because of the food supply chain. It starts with the farmer who has a lot of land expenses. They pay their land expenses by increasing the price of their food for more than it costs to grow it because they have to make a living. Then what also increases the cost is the fact that you have to ship it across the country. So you’re putting it in a truck driving it to Washington, DC from California, and then the grocery store has to increase the price of that food so that they can cover the cost of transportation, the cost of keeping their lights on, the cost of food spoilage when not everybody buys all the food in the store, and still make a prof it.

So then we started questioning how do we change this model? How do we make it better? What is a cheap way of producing a high yield of local produce that’s not going to cost a lot of money? And how do we make it affordable to somebody without having to rent out a warehouse to sell food? And we as a nonprofit, we sat down and we were like, okay, with the research that we’ve just done. In the customer inquiry and everything that we know about food in the way it’s produced, how can we do it?

BP: And what did y’all come up with?

EH: We started getting into automated hydroponics.

BP: Which are...?

EH: Hydroponics is a method of growing where you recycle water basically in a system that cir cling like a loop. So if you imagine from your traditional farm, imagine if you could have a bathtub of water and then just take from it when you need it and slowly drink all of it, versus drinking from a fountain that’s always on. It saves a lot of water. And then you’re recycling it so the roots just take what they need. So imagine if you had a tray or container and you set some plants on the top of the container and you fill the bottom of the reservoir with water. Then the roots slowly suck up all the water so none of it is getting absorbed by soil or anything like that and going to waste because at the end of the day, plants don’t really need soil, what they need is nutrients. So if you can get that water, fill it with nutrients and then allow the plants to absorb it instead of using soil and wasting all that water on soil, land, and space. Growing plants is cheap!

The great thing about putting plants in water and not soil is that you can build up. So think about cities right? If you have hydroponics what you can do is you can get something like a shelf and put stacks and stacks and stacks of plants on shelves, and then just use a water pump to recycle that water through all the levels of shelves. And that’s basically what I do. Automated Hydroponics is basically what Hydroponics is, but we decided to automate it.

So what’s another barrier to entry to getting food or to tech or to things like this? People do not have the time to be growing their own gardens. Even if it’s hydroponics you don’t have the time to be tending to the water. You don’t have the time to be checking the nutrients. That’s why people don’t grow their own food. It’s hard enough to cook your food at night! So how do we make it automated so that people aren’t having to worry about this all day while still keeping the growing local? Okay, computers! Things are already automated for you. So then we started getting into automation, asking how we can make this completely automat ed so that all you have to do is replace the system with water every three or four weeks so your plants go from start to finish in the machine.

It’s circling, it’s dosing the nutrients for you, and you’re getting a high yield of plants in a small amount of space because it’s going up. You’re not using soil and all you really needed to seed water and some nutrient solution. Nitrogen, Potassium and Phosphorus.

BP: This sounds really dope! How are you going about making this technology accessible to those who experience food insecurity in DC?

EH:

So we realized at the Food for Thought Foundation that we can teach this system to the com munity. I’m not a computer science student. I have no background in computer science. I literally picked up coding a year ago, and in six months I was able to make a working pro totype of a hydroponic system. So if I can do it, everybody can do it. It’s not that hard, but there are people trying to make it seem like it’s hard and unattainable so they can privatize it.

So what we’ve developed is a hydroponic system that can be taught to high school students because who wants to learn how to do this stuff and needs skills that are worth a billion dol lars right now? High school students in food deserts! So we started partnering with Woodson High School and we just give them weekly lessons on hydroponics, coding, and growing. We teach them starting off with the social aspects of [food insecurity] to help them understand why we’re doing it like this. And then we teach the kids how to assemble the systems and we’re doing our pilot program this semester, where they actually assemble this system. The idea is once we can get these farms going at enough schools and the students know how to assemble them, all they have to do is harvest the produce and put it in a fridge outside of the school, which we supply with their curriculum, so anybody can come to the fridge and pick up produce. The school board will buy the curriculum like any other coding or computer science curriculum because it’s relevant to what [students] need to learn for future skills. So your food is completely free because 1. it’s automated growing, and 2. you don’t have to pay for it because the school board does!

BP: How much produce do the vertical farms produce?

EH:

That’s a good question. So the proof of concept system that we’ve made right now can make about 12 plants in three weeks, but it’s a really, really small machine. Think about the size of a bedside table. So if you had one the size of maybe like a fridge or the size of maybe a really big filing cabinet, you could probably get to like 30 to 40 plants every three weeks. It’s a re ally high yield for a really small space. Think about growing 30 to 40 plants outward, that’s a lot. So, if you can put multiple [vertical farms] on one campus site, you’ve got enough to feed a couple of families. And we’re not saying that we have the solution to food insecurity. But what we are saying is that we have a better model than what’s going on right now. So we’re starting with that with produce share. And that’s really how we started the foundation and what we’re doing now.

BP: I know Food for Thought also does quite a bit of research which has been supported by vari ous initiatives, could share more about that?

EH:

Yeah! When we were doing this, the way that I did this was through the National Science Foundation (NSF) iCorps program which funds college students to go out, interview com munities, find solutions to problems and then start solving those problems with a proto

type. We got about $5,000 to do it the first time. And we spent that just on materials to learn how to code and build a machine and that’s what we’ve got right now. We’re realizing that it doesn’t need to take $5,000 to build one of those machines. It’s just like human error be cause you’re learning as you go. The Clinton Global Initiative Foundation, specifically the university program, was also a helpful resource. It basically just connected me with other entrepreneurs and students who are trying to solve problems for social good with socially oriented companies. That was really helpful because I got to meet and network with people. For example, when I was networking with nonprofits, I would go to my mentor in CGI and ask, “Oh, do you know any nonprofits in the area who would be willing to talk about this? Who does this? That was very helpful.

BP: How have your interests changed since going through this process of starting the Food for Thought Foundation? What other initiatives have you gotten involved in, if any?

EH:

When I first started Food for Thought, I was not studying public health. I thought I wanted to be an international relations scholar and do global health work. Global health is good, but at the end of the day, I did not want to do diplomacy. My interests definitely changed when I started the nonprofit because I realized that I care about food insecurity because of my fam ily and their health issues at the end of the day. The way that I’ve seen that food insecurity impacts people, and on a larger scale that is not necessarily directly relevant to what I do now, but it’s something that I have a goal that I have in my future is to change the way that we view healthcare here.

Why do you think Scandinavia and socialist countries have really healthy methods of pro duction? Because they have an incentive to keep their population healthy, because they’re not making money off of doctor’s visits and treating people like this. So I’m really starting to think about how healthcare affects everything and that’s when I got interested in the idea of being a public health physician, which is really what I want to pursue. A public health physi cian is somebody who looks at health on a population level. So what I’m doing now, basically how we went to the community and found a solution for it, is our attempt at trying to treat the health issues that stem from food insecurity. I want to do that in the future with larger issues and insecurities.

Because I wanted to be a public health physician, well you need a medical degree for that. I was like, “Oh no, I haven’t done any of the stuff that you need to go to medical school” be cause I wasn’t interested in private practice medicine. So how do I get clinical hours? How do I volunteer and get clinical hours like treating patients while not sitting in a doctor’s of fice all day doing insurance claims? I was like, “oh my god, I’m gonna be an EMT!” So then I started volunteering at the local fire department. And I’ve learned so much about emergen cy health care and the way it works from the Bethesda Fire Department. I like it a lot. There are so many social factors in our environment which impact our health that I think we could solve if we had more public health physicians. That’s how I got into all that stuff.

BP:

:I know you’re also into research, could you share more about your work?

EH:

There’s two types of research that I’m doing right now on campus. So yeah, we’re doing all

this research, like how can we really define the food desert and then what we’re gonna do is we’re gonna take all this policy that’s been put out in DC and actually track the outcome and meet that grant that Mayor Muriel Bowser did with all those restaurants. It did not combat food insecurity. We know Food deserts are changing. DC has passed so much food policy. Mayor Muriel Bowser, I think she gave away something like a million dollars just last year to try and end food insecurity. And you know where that money went? It went to restaurants! Clearly there’s money and clearly there’s a want to solve food insecurity, but like something in the bureaucracy is making sure this is propagated to restaurants. Obviously they’re food establishments, but that’s not security.

So we were like, “Okay, there’s so much food policy that’s been passed in DC. Why hasn’t it done anything? Well, let’s make a policy tracker.” We’re doing all this research on how we can really define what a food desert is. Then what we’re gonna do is take all this policy that’s been put out in DC and track the outcomes, and analyze which strategies are most effective to combat food insecurity and hopefully inspire better policies to be made.We as a nonprofit cannot impact or lobby politicians, but we can give people who want to do that the informa tion to do that. So that’s what we’re doing with that research.

My other research is about how we can make food systems better through automations and different systems of food production and supply. So right now on all sides and trying to set up a vertical farm so that we can test the nutrient content of what we grow first to make sure that what we’re growing can produce something that is just as nutritious and healthy and not GMO or Monsanto-infected. Because those things will ruin your brain! Dr. Holton, here on campus. She has a really cool professor. She’s doing research on how food additives can give you diseases like Alzheimer’s or can contribute to things like Alzheimer’s, Dementia or early onset brain degradation, things like that. And these companies that are doing this stuff on the majority of our food supply, like it’s crazy!

BP: What do you wish more people knew about food insecurity and how food is produced?

EH: What I really want people to know about food insecurity is that it’s a structural problem that needs a structural solution. We really need to re-examine the way that we produce and grow food. Another thing that I want people to know is where your food comes from. Think about the miles it takes for your food to get on your plate, where it’s grown from, and what’s going into it. Look at the ingredients on your package, like there are actual carcinogens in the food that you eat? I’m not trying to be like hippie vegan (like no hate vegans are cool but) these things will give you autoimmune disease. Be intentional about where you get your food from. Eat local. Oh, I cannot stress that enough. If you can go to the farmers market or if you have a local producer selling something for the same price or a little bit more like eat that because these companies do not care about you. Publix, Walmart, they may say they care about you in a commercial but they do not care about you. They want your money.

BP: Good to know…What would you say is your favorite part of your work?

EH: Definitely my students. I’m teaching students how to do something that’s valuable and they will actually use in the practical world, and we’re going to grow food. I like my students and

I get to see the direct impact that my foundation has on them. I’m not going to be a teacher forever, but I really like it.

BP: What advice would you give to someone who’s passionate about an equally environmental and social issue like food inequity, and wants to start an organization like Food for Thought?

EH:

You want to start your organization, go ahead and incorporate it. But before you launch a program, just sit down with your community and talk to them. Host a focus group, maybe ask your mom to cook some food and invite people to your house. I know inviting strangers to your house is kind of hard, but talk to people in the community because you will find an answer. You will find people who can give you the means to start a solution that is really via ble to what you want to do because you don’t have to do it alone.

BP: How can students, faculty, and members of the AU community support Food for Thought’s work?

EH: Come volunteer with us! Donate money, if you can, but we are looking for people who want to be committed members of our team. I mean people who are passionate volunteers and are not looking to come in for six months, but who want to stay with us just because they’re involved in our mission. And faculty, please give us your knowledge.

BP: Where do you see the organization going growth-wise?

EH:

I want to expand to more cities. The whole point of the way that we’ve created our solution is that we don’t need to be involved in it. It’s literally a package that cities can take and im plement in a way that works for them. If you don’t want to do school based, you can imple ment it in your community centers and churches. We want to expand it everywhere because we are a decentralized food production model.

BP: It seems like you, and Food for Thought, are on track to do amazing things in public health. Thank you for letting me interview you!

EH: Of course!

The American University Community Garden is an established and welcoming community within the university. The community garden club provides an a venue for students to connect with the environment in an honorable way.

This was clear when I attended a community garden meeting with Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Incorporated, Lambda Zeta Chapter accomplishing their Enhance Our Environment program initiative with a focus on community and home gardens.

When attending the Community Garden club meeting on October 22nd, we were met with the discussion of the Honorable Harvest. The idea of the Honorable Harvest came from Indigenous people who believed in the principles and practices that value the ex change of life for life. The Community Garden club and its mem bers encourage inclusive practices, especially with recognizing the contributions people of color and Indigenous people make to the environment.

Trevaughn Ellis, a junior at AU studying Biology, is the Co-Presi dent of the Community Garden club. While conducting an inter view with Ellis, he shared why he joined the community garden and his goals for the future of the garden. Read below to see how Ellis plans to contribute to the community garden and how oth ers can do the same in its attempt to prioritize the environment around them.

The Blackprint: Why did you join the community garden?

TreVaughn Ellis: Actually, one of my friends started talking and we have an environmental science class together; she encour aged me to go. I always liked environmentalism. I always liked the outdoors.

BP: Are there any particular goals or initiatives for the AU com munity?

TE: Yes; for me personally, I want to get more people of color, specifically Black people, involved inside the community garden. I know one of the challenges for me is that it is a space that we have not primarily been seen in. This is weird because there’s been a lot of erasure of Black and Brown involvement in environ mental spaces [...] That is one of the initiatives I have- getting us more involved.

BP: Can you speak more about the history of Black people and people of color participating in environmental studies or com munity gardens?

TE: It was the Indigenous people who first started these practices of environmental consciousness, caring for the environment, and respecting or abiding by the rules of the Honourable Harvest.

There has been an erasure or type of separation of communities of color. For example, the act of being outside is something that has not been accessible to us as it should be but here at AU we have a great community and a lot of avenues for people to do that type of thing.

BP: Do you have any theories as to why we are no longer repre sented in those spaces?

TE: There is probably a longer conversation [...] There’s always been a lot of people of color who are doing the environmental work, but there is always room for more.

BP: How are you looking to get more people of color to participate in the community garden?

TE: I know one of the hurdles for me was that I had never done a lot of outside gardening [...] Also, there is the element of commu nity in the community garden. One of things that really helped me was having at least one friend that I knew there and realizing that it is not that serious. It is not as tough as people may think it is.

BP: Do you all have events planned soon for the community gar den?

TE: If you go onto Instagram, you will be sure to see them. Our username is @i_begyourgarden.

BP: How do you feel about the move of the community garden?

TE: In the beginning, the move of the community garden was a betrayal because we had to find out all the information on our own. But now, we have been given an opportunity and platform to reimagine what the space looks like; the university is now in vested. They showed that they are invested. Now, the community garden has so many intersections and so many new groups getting invested. We are completely reimagining what the community garden looks like and, to me, that is very exciting because it in volves a new community garden that incorporates more space. A community garden that is more accessible. A community garden that provides opportunities for more people to get involved who never thought of it before. The move started off as something neg ative but now it is something that is really positive.

BP: Are there any insights about the move? How can the AU com munity show support for the garden?

TE: One; get involved. Come to the community garden. Two; we are going to need all hands on deck when we do the move, so there is something for everyone in the community garden.

I promise you that.

My name is TreVaughn Ellis, and by circumstance my name works well with what I do. I am a beekeeper, a gardener, and a scientist. It seems to be a coincidence that: “tree”, the provider of life on this planet finds itself in the name while it’s being there is completely unrelated to nature. I am a Junior at American Univer sity studying Biology! I am a houseplant dad, I work in the campus hive, and I am passionate about the inter sections of the ocean and us. I also like skating and art.

We need to reconnect. There is an unseen connection between us and nature that needs to be rebuilt. There is a peace to be found in walk ing with no music and hear ing what the birds and bugs have to say. There is beauty to be seen in the changing of the seasons. There is love to be experienced in the simple sugars of a fruit given to one by a tree.

I would like to see more people connected. Even if it is foreign or scary. The doors are open, bring a friend and walk through.

These aspects are what empower students of color to thrive, especially at a predominantly white institution. When first coming to American University as a Native student, I was immediately confronted with the absence of a space for Indigenous students. Through the School of International Service’s Undergraduate Council and with help from Students for Change, I created the Indigenous Initia tive, an Indigenous student-led organization that ensures an inclusive environment where Indigenous students from all areas and backgrounds of the world feel valued, included, and empowered to succeed. Indigenous students are able to connect, support, and collaborate with each other. We are involved in dialogue addressing issues at AU, larger-scale ad vocacy, and work toward dismantling the impacts of settler colonialism.

have to face.

This reality somehow became more relevant as Indige nous Initiative did. New challenges arose, performativity, overstepping, and ignorance in relation to Native issues. In response to these challenges, there was a need to promote coalition and unity, a community that brings together those with shared experiences, for students of color and by stu dents of color

AU’s Black, indigenous, and other communities and organi zations of color have built the foundations for empowering students and building community. This semester I recog nized this significance and came out gaining support from these organizations. A unifying alliance now exists made up of students who experience the effects of settler colonialism, and organizations involved in decolonial work including Students for Justice in Palestine, Hawai’i Club, and Students for Free Tibet.

Navigating a PWI as a student of color continues to have its challenges no matter what. Experiences include anywhere from microaggressions, to Eurocentric curriculum, to tokenism, all being a persistent occurrence Black, Indigenous, and other students of color

Working hand-in-hand with leaders from these organizations, we were able to create a network of students where we share our ex periences, do advocacy work, and learn from each other. This coalition coming together has been so amazing, and I am proud of the work we have done and the sense of belong ing that I and other students can experience. It is through collaboration and solidarity we became the community that was so needed.

Working with Sacred Lands, Native Hands has also been gratifying as I am able to work with Natives who are also passionate about the same issues I am. This includes work towards land back initiatives, tribal environ mental advocacy, community development, etc. With Sacred Lands, Native Hands, I am involved in social media working in edu cation and advocacy. Having this position provides me with a creative outlet and work in art activism which is another one of my passions, specifically in exploring how the media plays a role in advocacy and educa tion. My artwork is also something that is important to me as it is an outlet for self-ex pression, and I am interested in art activism. I have learned that art can serve powerful political messages and become an outlet for marginalized issues. Knowing this informa tion, I hope to use art activism in my social media work and beyond.

Working with Sacred Lands, Native Lands, I am also able to learn from Indigenous leaders and, notably, their work toward reclamation of Miwok Lands in Northern California and for their application of Indig enous Ecological Knowledge (IEK). They also are working to become the first Native-led nonprofit to provide pro-bono advocacy and legal services to underserved tribes in the western region of the United States that are seeking to regain access to their tradition al territories. Working with Sacred Lands, Native Hands, I also experience community, coalition, and unity as these are themes that are common within Native spaces.

As I continue my work at American Universi ty, I hope this coalition will grow and thrive, and Native students will be welcomed into community and experience a sense of belonging.

My name is Olivia Olson, I use she/they pronouns, and I am Indigenous to the Mexico-U.S southern border area.I am from Fort Collins Colorado and Port Charlotte Florida. I am currently a Junior with an International Studies Major with a focus on Identity, Race, Gender, and Culture and Global Inequality and Development. I am also a Studio Art minor. I am the director and creator of the Indigenous Initiative at AU and am involved in an organization called Sacred Lands, Native Hands which works to restore ancestral homelands to the hands of Indigenous people and Indigenous ecological knowledge to the land.

This song is classic, rem iniscent of the 70s, when trees were green,the sun was shining, skies were blue, and life was simple. This song transcends you into another universe to be carefree and simply vibe.

This instrumental song lumes the calmness of rain within the background and an 808 beats making you want to zone out. This in strumental is a simple melo dy crossed with hints of jazz, perfect for a walk on a rainy day.

This 80s groove influenced song takes you on a trip of walking on earth and flying in the sky. This song gives no other choice but to bob your head.

This song lifts you to another universe of no worries and calamity. This song makes you want to put in your head phones and float away.

This upbeat song makes you want to sing to your lover on a sunny day. This song is a feel-good that reminiscences on young naive love and happiness.

This song brings you back to the blue skies, sunny days, fluffy clouds while sunbath ing. This song is a feel-good groove with a relaxed mel ody that pulls you into your imagination.