9 minute read

Al Finegan

The Charles Eaton

MASSACRE PART 3

Advertisement

As 1834 drew to a close, John Ireland and little William D’Oyly slowly recovered from the trauma of the wreck and subsequent massacre and settled in to live happily with the natives on Murray Island. Ireland lived in the same hut with Chief Duppar and his family. His job was to manage a plantation of yams, and occasionally assist in harvesting turtle and shellfish. Meanwhile, William lived a contented life being well cared for by his adopted mother and her family. From time to time a European trading vessel would arrive, usually Dutch, or British from India. Ireland tried several times to board visiting ships but was held back by the locals. He knew they were fearful of retribution if he escaped and told his story. On 18thSeptember 1835, the trading vessel Mangles under the command of Captain William Carr, anchored off Murray Island. Among the natives who came out in canoes to trade was John Ireland. He told the sailors the tragic story of the wreck of the Charles Eaton but when he was offered a chance to escape, he was reluctant, saying he was now happy enough and would not leave without William. Next day Captain Carr landed on the island to investigate the story and, sure enough, saw the young boy William D’Oyly, whom the natives made no attempt to hide. When Captain Carr eventually returned to Sydney, he told the local press of the two young castaways on Murray Island. During 1835, more stories of white people being held in the Torres Strait reached Sydney from visiting ships. Dutch newspapers arriving from Batavia also reported being told of the white “pets” of the Murray Islanders. Meanwhile the five deserters who abandoned the people on the wreck of Charles Eaton reached the Tanimbar Islands - about 450 km north of Darwin where they were captured by the local natives and put to work. Thirteen months after their capture, the survivors were permitted to leave, reaching Batavia on 6th December 1835. Piggott arrived seriously ill with fever and died in hospital. The other four were arrested and required to make sworn depositions regarding the wreck of Charles Eaton. They stated that they had stayed on the cutter near the wreck for the rest of that day and night. Having no anchor, they were exhausted from rowing to hold their position. They swore that in the morning they could see no sign of life on Charles Eaton, and they concluded all had been washed off and drowned during the night. Their depositions reached England in June 1836. About the same time, another schooner captain, who had come through Torres Strait and just arrived in London, reported that he had seen white people being held captive by the Murray Islanders. With reports already appearing in London newspapers about the loss of the barque Charles Eaton in the Torres Strait, and the supposed captivity of some of her passengers and crew, Secretary for the Colonies, Lord Glenelg decided to act. He sent a despatch to Sir Richard Bourke, Governor

By: AL Finegan

of NSW, stating ". . .. it will be

highly desirable that you should adopt such measures as may appear to you most advisable for ascertaining the fate of those unfortunate persons, and for rescuing them.... "

BY: Al Finegean About the time that Bourke received Glenelg's despatch, a copy of the Bengal Herald of 28th February 1836 reached

Sydney. It reported that as a result of lobbying by Captain

D’Oyly, grandfather to young

William, and the receipt of other reliable information, the Governor-General of India had exerted his influence to implore the Governor of

Bombay (now Mumbai) to mount an expedition to recover the persons supposed to have survived the wreck of Charles

Eaton. The report stated that the East India Company's armed brig of war, Tigris, had departed for Torres Strait in search of survivors.

Back in Sydney, Governor

Bourke decided to act immediately. The only vessel available for the rescue was

HM Colonial Schooner Isabella.

At great expense she was fitted out in preparation for

her mission. A crew of five officers and 25 men were recruited. Isabella was outfitted with six cannons, and an armoury of muskets and cutlasses was installed. Bourke's instructions to its Captain, Charles Morgan Lewis included, “… search and

enquire thoroughly wherever he landed and to conciliate with the natives - whilst using the utmost precaution to prevent a surprise

attack”. The evidence to assist in the search was sparse and conflicting. Among the reports were the depositions taken at Batavia that indicated there could not be survivors, whilst Carr's and other captains’ statements claimed that there were survivors on Murray Island. Bourke advised Lewis to proceed directly to Murray Island. He could not have given better advice. On 3rd June 1836, Isabella sailed off for Torres Strait on her belated mission of rescue. She dropped anchor at Murray Island on 19th June 1836. Four huge 12m long canoes came out, each containing 16 men. They were fitted with outriggers and with a large platform amidship on which were tortoise shells, coconuts, plantains and other articles of trade. As they approached, they made signs of friendship by rubbing hands over their abdomens and calling out, "poued, poued”, meaning peace, peace. They held up items of trade and asked for "toree" and "tooleck", knives and axes. Their language was not entirely unknown to some on-board Isabella, who pretended by signs not to understand, in the hope that the natives would bring out a white man to interpret. This ruse failed, so axes were tantalisingly displayed as bait. Then by signs, Lewis asked for the white man to be brought out, which they declined. Soon the locals realised there was to be no trade without producing “Wak” (John Ireland). Their desire for axes had overcome their desire to retain John. A canoe was sent to shore to fetch him. An hour later the canoe returned with a white youth, aged about 17. As the canoe came towards Isabella, the lad showed mixed emotions of fear and delight. A stern Lewis demanded silence, and in an uneasy atmosphere, he quietly asked John for the name of the ship in which he had been wrecked. After an anxious moment, John replied, “Charles Eaton”. Lewis then asked John if there were more survivors, and he replied, “One, a child aged about five”. The tension increased when Lewis told him to climb aboard, triggering the natives to seize John, demanding axes first. The axes were tossed down, and John clambered aboard. On the beach, Lewis could see little D'Oyly, who was holding hands with one of the women. Now having the advantage of Ireland to interpret his demands, there would be no mistake in his message to the natives. Either they produced the child in return for axes, or force would be used. The sullen natives returned to shore. After waiting for some time while staring at an empty beach, Lewis ordered the gun ports opened, and the cannons run out. When there was still no movement on the shore, he ordered a cannon to fire a shot at the water near the beach. The sudden deafening bang and huge splash had the desired effect. The child, surrounded by the islanders, was brought to the beach clinging to a young, sobbing woman, who was kissing Willy repeatedly. Duppar, resigned to the inevitable, pulled Willy from the grasp of the woman, stepped into a canoe, and was rowed to Isabella. Willy was bawling, clearly terrified and kept pointing to the shore. Duppar forcibly released Willy to John, took the axes from Lewis, then solemnly returned to his island. Isabella weighed anchor and set sail.

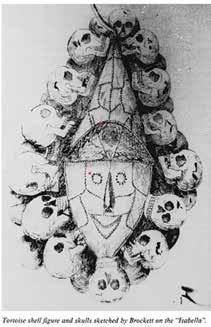

Lewis needed more details about the massacre. John struggled initially to form sentences, but after a few days, his English language skills returned. According to Captain Lewis, “Young John was deeply

imbued with native superstitions…. the little boy, Willy D’Oyley, spoke nothing but the

island dialect. He is a fine boy.” When an emotional Ireland finally told the terrible story of the massacres, a horrified Lewis became more determined to search the neighbouring islands to find the murderous tribe and deliver justice. Isabella anchored off Masig Island where they were told by the locals that it was the men from Aureed who had committed the massacre and taken the skulls back to that island. Taking a volunteer from Masig as guide, Isabella sailed off for Aureed and dropped anchor. Lewis led an armed party ashore but found the village deserted and showing evidence that it had been hurriedly abandoned. In the centre of the village, the men found a decorated hut, and in it a huge mask made of a single painted turtle shell surrounded by human skulls. Some appeared to be of European origin. They took 41 skulls and mask, then set fire to everything, including plantations of tobacco, leaving the island a smoking charred ruin. Isabella called at other nearby islands, but all had been deserted by the natives for fear of being punished. Days later, Thomas Harrison, bound for Java from Sydney, came into sight and from her master, Lewis learnt that Tigris was somewhere in Torres Strait also searching for survivors. Whilst Lewis was on board Thomas Harrison, Tigris, under command of Captain Iggledson, hove into view. The surgeon of Tigris examined the Aureed mask figure and its skulls and pronounced that 17 were European. Iggledson insisted that he take young D'Oyly to his grandfather in Calcutta, which Lewis declined in view of his instructions from Governor Bourke. As SE trade winds would not permit a return to Sydney down the Australian east coast, both ships headed west. The following day, Tigris was about 5km ahead of Isabella when Lewis heard cannon fire. He knew this to be a distress call. As Isabella closed with Tigris, Lewis could see that she had struck a reef and that her rudder had been ripped off. With difficulty, the crew of Isabella in their long boat, towed Tigris clear of the reef and lashed her to Isabella's quarter. The ships sailed as one for the nearby Raffles Bay where a new rudder was built. On 24th August both ships arrived in Kupang, Timor, where they separated - Tigris for India and Isabella for Sydney via Cape Lewin, WA. She reached Sydney on 12th October 1836. On arrival in Sydney, Lewis and the two boys immediately became local celebrities. John gave a narrative of his experiences to Governor Bourke in council, and afterwards was presented with a first-class passage to England. He later released a popular book on his adventures and went on to have a successful life. On 17th November, at the direction of Governor Bourke, the 17 European skulls were given a Christian funeral service and interred in a monument built in the form of a huge altar stone recording the tragedy by which they perished. The monument is now located at the Bunnerong Cemetery at Botany Bay. Lewis escorted William D'Oyly to London on HMS Buffalo arriving in May 1838 and delivered him to grateful relatives. In September 1839 Lewis arrived back in Sydney and immediately applied to Governor Gipps for the reward he had been promised for a successful rescue. Gipps rejected his application and instead appointed him as the harbour master at Port Phillip. In December 1841, this brave man suffered a severe stroke and became destitute. Friends brought his case before the Legislative Council. Finally, in 1845, he was belatedly awarded the promised £300 for his successful rescue mission. He died soon after, aged just 40.