5 minute read

WHY WE NEED TO THINK ABOUT BUSHFIRE

Bushfire is a serious threat to property and lives in Hobart. Changes to the planet’s climate mean bushfires are increasing in frequency, intensity and extent around the world, including here in Tasmania. The City of Hobart manages bushfire risk in our parks and reserves, and maintains fuel breaks between reserves and private property. But these steps will only help protect properties that are well-prepared for bushfire. It is the responsibility of each household to prepare for and manage their own bushfire risk. To protect your home and family, there are important things you need to do before every bushfire season. This action plan explains what causes bushfires, how we can manage the risk, and what you need to do to protect your home and family from bushfire. The increasing threat of serious bushfire means we all need to make changes to how we think about and prepare for bushfires.

A brief history of fire in Tasmania

Fire has been part of Tasmania and Australia for a very long time, certainly before Europeans arrived. A core sample containing pollen and charcoal taken from deep sediment in a lake on Flinders Island off the coast of Tasmania showed Aboriginal people were actively using fire as a management tool at least 12,000 years ago. The first reference to bushfires in Australia by European explorers was in Abel Tasman’s diary entry on December 2, 1642 during his exploration of Tasmania’s east coast.

A short time before we got sight of our boats returning to the ships, we now and then saw clouds of dense smoke rising up from the land, which was nearly west by north of us, and surmised this might be a signal given by our men, because they were so long coming back, for we had ordered them to return speedily, partly in order to be made acquainted with what they had seen, and partly that we might be able to send them to other points if they should find no profit there, to the end that no precious time might be wasted. When our men had come on board again we inquired of them whether they had been there and made a fire, to which they returned a negative answer, adding however that at various times and points in the wood they also had seen clouds of smoke ascending. So there can be no doubt there must be men here of extraordinary stature. This day we had variable winds from the eastward, but for the greater part of the day a stiff, steady breeze from the south-east.

Parts of the Tasmanian landscape reflect these past burning practices. An example of this fire-shaped landscape can be seen today in the open button grass moorlands found throughout the Tasmanian highlands. Aboriginal fire practice across Australia was severely disrupted by the arrival of Europeans and as a nation we have not taken the time to learn with Aboriginal people to manage fire across the landscape.

How often do we have major bushfires?

Because fire records in the past are limited, and records in the early days of European occupation are almost non-existent, a clear answer to this question is not easy. Tasmania has seen considerable fire activity across the landscape and it appears to be increasing in frequency, intensity and extent. Records kept since the early 1800s show significant fires in Tasmania across a number of years. In 1954 a large fire threatened the southern outskirts of Hobart and, along with other fires that burnt that year, led to the establishment of a new Bushfires Act, which was designed to limit the damage caused by fires lit inappropriately and escaping onto other properties. It was not until the 1967 Black Tuesday bushfires, which left 62 people dead, injured 900 and destroyed 1293 homes, that the Rural Fires Board was established, leading to the formation of the Tasmania Fire Service.

The changing landscape

In 1967 the Hobart bushfire, which remains a defining event in Tasmanian history, moved so rapidly that many people had very little time to prepare for the catastrophic impact as it approached the capital city. But a bushfire does not have to be as intense

Fires throughout Tasmania’s recent history.

or widespread as the 1967 Hobart fire to have significant impacts on people’s lives. Over time, the memories and experiences from major bushfires fade. People are continually moving to Hobart from elsewhere in Tasmania, Australia and the world. Many of these new residents will have little knowledge of the landscape’s fire history. Increased residential development, particularly on the urban fringe, means more people than ever now live close to bushland. Houses have been built on the edge of steep bushland valleys and ridges at places like Mt Nelson, West Hobart and on the edges and in the foothills of kunanyi/Mt Wellington. Most of these areas were developed at a time when there were few, if any, planning laws requiring new houses be built to withstand bushfire. The bushland in and around Hobart is extremely important to the health and identity of the city and the people who live here. We are intimately connected with nature and wilderness. Whether it is a quiet afternoon spent in one of our many parks, riding or walking to work along the Hobart Rivulet, or a day spent walking on kunanyi/Mount Wellington, some of our best and most cherished times are spent in nature. But having nature on our doorstep comes at a cost. It means we must manage the bushfire risk in our bushland reserves to minimise the threat to people, homes and infrastructure. At some point a bushfire will occur in bushland surrounding Hobart. And while the bushfire risk cannot be completely removed, with careful thought, hard work and the cooperation of our entire community, it can be reduced. The City of Hobart undertakes many actions to reduce the risk of bushfire for the people of Hobart. Details can be found in the City of Hobart Fire Management Strategy.

The bushfires which attacked Hobart and adjacent areas of Southern Tasmania in the summer of 1966-67, peaking on 7 February, produced one of the most damaging natural disasters ever experienced in Australia. In this case some 653,000 acres of Southern Tasmania burned. In the short space of four or five hours on that ‘Black Tuesday’, the burning caused the deaths of 62 people, destroyed about 1400 buildings (mostly homes, but also factories, schools, hotels, post offices, churches and halls), savagely disrupted communications and power facilities, and destroyed about 1500 cars and trucks. The fires also dealt massive damage to surrounding farms, pastures and livestock, and total monetary damage was assessed at about $40 million (at 1967 values).

Reference: Wettenhall 2006

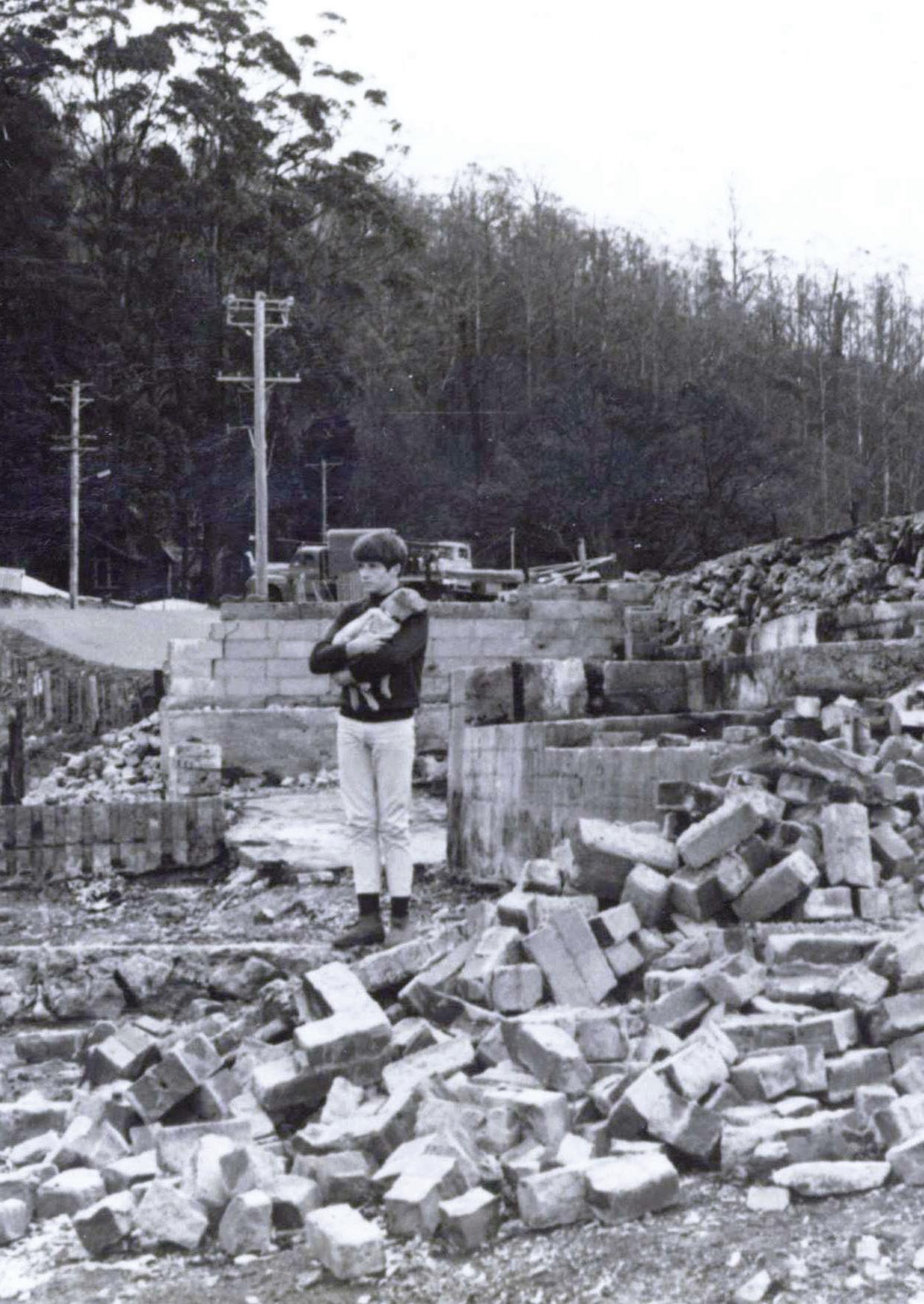

Charles Roberts and his dog, Elsa, survey the ruins of the Fern Tree store.

Photo: Stuart Roberts