OUR MAGAZINE WILL RELAUNCH AS LEARN MORE

INNOVATIVE STORYTELLING

IMMERSIVE FEATURES

THOUGHT-PROVOKING ESSAYS

COMING APRIL 2025

OUR MAGAZINE WILL RELAUNCH AS LEARN MORE

INNOVATIVE STORYTELLING

IMMERSIVE FEATURES

THOUGHT-PROVOKING ESSAYS

COMING APRIL 2025

As the lights of Chanukah begin to shine, we are reminded of the power of hope, resilience, and unity This year, more than ever, our hearts are with our brothers and sisters in Israel.

The challenges they face are immense, but with our unwavering dedication to providing humanitarian aid, vital medical equipment, and mental health support, we can offer together a beacon of light in these difficult times.

May the miracles of Chanukah inspire strength and healing for all those in need, and may we continue to stand together as one people, bound by our shared values of compassion and care.

Wishing you a Chanukah filled with peace, warmth, and the hope of brighter days ahead

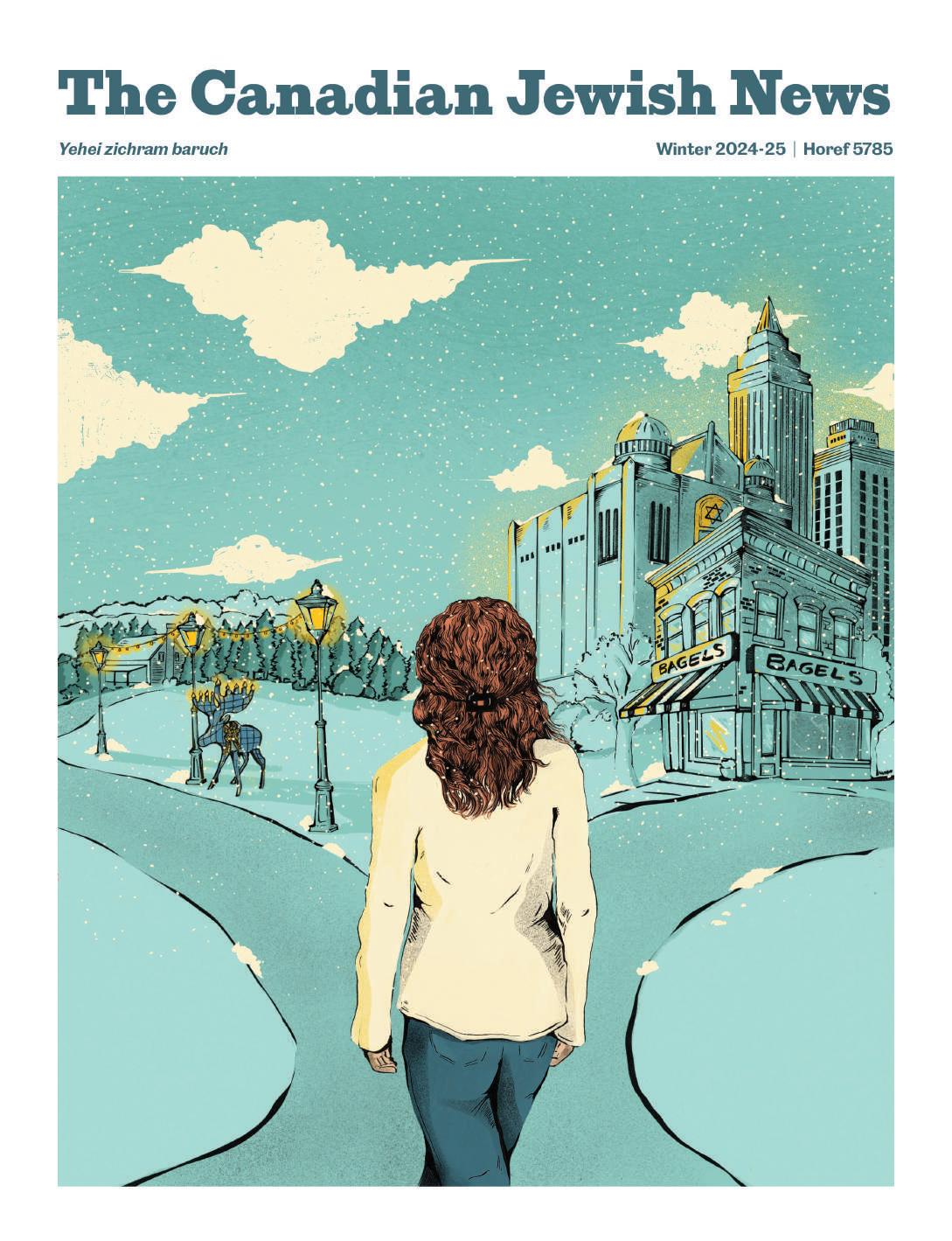

Chloe Zola (cover, p22 and

32) is an American illustrator

living in San Miguel de Allende

Mexico whose work is often motiv ated by social justice

issues and current affairs.

Her interests include yoga, chocolate chips, and learning

Spanish at a glacial pace.

Ira Basen (p48) is a Toronto-

based writer and educator,

and a long-time CBC

Radio program producer

and documentar y maker.

Sports and Jews are two of his favourite topics, and

he welcomes any and all

opportunities to combine

the two

Sarah Mintz (p.32) is a graduate of the English MA program at the University of Regina. Her flash fiction collection handwringers was published with Radiant Press, and her debut novel, NORMA, is available now from Invisible Publishing (2024) Find out more at smintz carrd co

Correction: In the article “What Do We Mean by Zion?” (Fall 2024) we wrote that the organization T’ruah holds anti-Zionist views. While the network and the rabbis within it aim “to lead Jewish communities in advancing democracy and human rights for all people in the United States, Canada, Israel, and the occupied Palestinian territories” they do not, in fact, identify as anti-Zionist We regret the error, which was corrected prior to online publication

For me, Hanukkah, like all major Jewish holidays, is primarily about family and tradition Growing up, the anticipation for the holiday was far greater than the feeling of any given gif t It was about the eight magical nights with my bubbe and zayde and spending time with my cousins and extended family not to mention what felt like an unlimited supply of latkes and sufganiyiot

Those traditions evolved as I was welcomed into my wife’s family Over the years, our families have expanded in size and shape, introducing new foods and new practices into our holiday celebrations

T h i s i s s u e o f t h e m a g a z i n e

f o c u s e s o n j u s t t h e s e k i n d s

o f c h a n g e s a n d a d a p t a t i o n s

o n a l a r g e r s c a l e : w e ’re d e l v -

i n g i n t o J e w i s h l i fe i n q u i e t e r

a n d m o re re m o t e p o c k e t s o f

t h e c o u n t r y. We ’re e x p l o r i n g

h o w p e o p l e h a v e a d j u s t e d

w h e re t h e re a re n’ t m a n y

o t h e r J e w s a r o u n d , e m b r a -

c i n g n e w w ay s t o c e l e b r a t e

t h e i r J e w i s h n e s s a n d f i n d i n g ,

i n t h e p r o c e s s , t h a t t h e y c a n

s o m e t i m e s b e t t e r c o n n e c t

w i t h t h e m s e l v e s , t h e i r c o m -

m u n i t i e s , a n d t h e i r re l i g i o n

C h a nge h as b e e n a t h e m e

at Th e CJ N re ce n t ly, to o We

h ave i n t ro d u ce d t wo n ew j o u r-

All this has been made possible by our dedicated and passionate audience, including our ver y generous donors Your suppor t ensures The CJN can continue to expand its coverage and that, in turn, is why we’ve been able to keep growing Over the past

n a l i s t s to ex p a n d o u r da i ly n ews c ove rage,

i n cl u d i ng a n e d u c ati o n b eat re p o r te r a n d

a Q u eb e c n ews c o rre sp o n d e n t We h ave

a l s o i n t ro d u ce d a m aj o r u p date to o u r

web s i te t h at m a ke s i t eas i e r to n avigate

a n d c reate s n ew o p p o r tu n i ti e s fo r yo u to e ngage wi t h u s d i re c t ly

Th i s m agazi n e, to o, i s ch a ng i ng I ’ m

t h ri l l e d to a n n o u n ce t h at , as o f t h e n ex t

i s s u e, t h e p u b l i c ati o n yo u a re n ow h o l d -

i ng i n yo u r h a n d s wi l l b e a ri ch ly re p o r te d, b ea u ti fu l ly re d e s ig n e d m agazi n e c a l l e d

Scribe Quar terly Th e m agazi n e’s n ew e d i to r i n ch i ef, Ha m u t a l D ot a n, h as b e e n sp ea rh ea d i ng t h i s p roj e c t fo r wel l ove r a

As we light the candles this Hanukkah, may their glow illuminate not only our homes but also our hear ts and minds Let the flames inspire us to embrace change and ser ve to light the way toward a bright future filled with hope, resilience, and peace

Editor in Chief Hamutal Dotan

Art Director Ronit Novak

Contributing Editors

Phoebe Maltz Bovy Avi Finegold

Marc Weisblott

Designer Etery Podolsky

The CJN

Chief Executive Officer

Michael Weisdorf

General Manager

Kathy Meitz

Advertising Sales Manager

Grace Zweig

Board of Directors:

Bryan Borzykowski President

Sam Reitman Treasurer and Secretary

Ira Gluskin

Jacob Smolack

Elizabeth Wolfe

MICHAEL WEISDORF, MBA Chief Executive Officer The

Cover: Illustration by Chloe Zola for The CJN

Printed in Winnipeg by Prolific Group

With the participation of:

Your support allows The CJN to report the news that matters to Jewish Canadians. It means we can provide daily content at no cost to readers.

Donate to The CJN today thecjn.ca/donate

Donate to The CJN today thecjn.ca/donate

A Happy He a lt hy

Ch a nu k k a h

Ch a g S a m e a c h

416 4 81 8 52 4

7 7 D u n f ield Ave nu e , Toront o , ON , M4 S 2 H 3

T h eD u n f ield . c om

M u s e u m o f t h e B

Th e M u s e u m o f t h e B i b l e i n Was h -

i ng to n, D C , h as u nve i l e d w h at i t

s ay s i s t h e o l d e s t J ewi s h b o o k eve r d i s -

c ove re d Acc o rd i ng to t h e m u s e u m ’s d ra -

m ati c cl a i m, t h e ti ny b o o k i s a rel i c o f a n

e ig h t h - ce n tu r y c ivi l izati o n o n t h e a n c i e n t

t ra d i ng ro u te kn ow n as t h e Si l k Ro a d, c re -

ate d by J ews l ivi ng as a m i n o ri t y a m o ng

B u d d h i s t s w h o r u l e d t h e B a m i ya n Va l l ey i n

m o d e rn - day A fg h a n i s t a n

Measuring approximately 13 centimeters by 13 centimeters, the book combines a variet y of texts writ ten by dif ferent hands, including prayers, poems, and what the museum says is the oldest known version of the Hag gadah, the central text of the Pas sover seder

Th e m u s e u m ’s cl a i m s rega rd i ng t h e

b o o k a re b as e d o n yea r s o f wo rk by a

tea m o f re s ea rch e r s ; t h e i r wo rk i s s l ate d to b e p u b l i s h e d i n a s e ri e s o f 1 0 e s s ay s i n A p ri l A n ch o ri ng t h e s ch o l a rly d i s cu s s i o n s u rro u n d i ng t h e b o o k i s a 2 0 1 9 l a b o rato r y te s t t h at u s e d c a rb o n dati ng to e s ti m ate t

in a cave near one of the giant Bamiyan Buddhas that were car ved into a mountain in ancient times and deliberately destroyed in an explosion by the Taliban in 2001, according to an ar ticle in The Free Press Sometime later, someone repor tedly tried without success to sell the book in Dallas, Texas. Then, following the 9/11 at tacks and the U S invasion of Afghanistan, the book’s tracks disappeared until 2012, when a rare book dealer photographed it in London The dealer, Lenny Wolfe, told The Free Press that he tried brokering a $120,000 (US) deal between a pair of private sellers and an unspecified Israeli institution, but that the institution turned down the of fer. Eve n tu a l ly, t h e G re e n fa m i ly, eva ngel i c a l C h ri s ti a n s b as e d i n O kl a h o

Prior to the drama of the lab’s result, the book had garnered lit tle interest in the decades since it was first found in Afghanistan A member of the countr y’s Hazara ethnic minority discovered the manuscript in 1997

l

el e d, “ E g y pt , c i rc a 9 0 0 C E ” A m u s e u m

cu rato r w h o was exa m i n i ng t h e b o o k rea lize d t h at i

The book will remain on display until mid-Januar y, af ter which it will be on view at the librar y of the Jewish Theological Seminar y in New York City

For the first time since the Second World War, one of Prague’s most historic synagogues held a Jewish worship ser vice Kol Nidre, the introductor y ser vice of Yom Kippur ending a hiatus that lasted more than 80 years and encompassed both the murder and suppression of Czech Jewr y Originally erected in 1573 and rebuilt af ter a fire in 1694, the Klausen Synagogue is the largest synagogue in Prague’s Jewish Quarter and once ser ved as a central hub of Jewish life It’s known as the home of several prominent rabbis and thinkers, from Judah Loew a 16th-centur y Talmudic scholar also known as the Maharal of Prague to Baruch Jeit teles, a scholar associated with the Jewish Enlightenment movement of the 18th and 19th centuries

On Erev Yom Kippur, about 200 people poured in for a ser vice led by Rabbi David Maxa, who represents Czechia’s community of Reform Jews That community was joined by guests and Jewish tourists from around the world, according to Maxa He saw the moment as a sign of Jewish life resurging in Prague, describing it as “quite remarkable that there is a Yom Kippur ser vice in five historic synagogues in Prague ”

Under German occupation in Second World War, the Klausen Synagogue was used as a storage facility Although the Nazis and their collaborators killed about 263,000 Jews who lived in the former Czechoslovak Republic, they took an interest in collecting Jewish ar t and ar tifacts that they deemed valuable enough to preser ve The Jewish Museum

in Prague was allowed to continue storing those objects, and the synagogue became par t of the museum’s depositor y.

Af ter the war, there were not enough survivors to refill ser vices in the synagogues of Prague The countr y became a Soviet satellite in 1948, star ting a long era in which Jews were of ten persecuted and sur veilled for obser ving any religious practices. The last Soviet census of 1989 registered only 2,700 Jews living in Czech lands

“During Communist times, it was ver y difficult to relate to Jewish identity,” Maxa says “People who visited any kind of synagogue were followed by the secret police, and only af ter the Velvet Revolution in 1989 did it become possible for people to visit synagogues without the feeling of being followed and put on a list ”

Af ter the end of communist rule, some synagogues returned to use by the few who still identified as Jews Two of the six synagogues that still stand in the Jewish Quar ter now are in regular use as houses of worship But the Klausen Synagogue, which was added to the UNESCO World Heritage list in 1982, remained par t of the Jewish Museum, hosting exhibitions about Jewish

festivals, early Hebrew manuscripts, and Jewish customs and traditions

Museum director Pavla Niklová says that returning the synagogue to use for Yom Kippur happened almost by accident. Maxa was asking if she knew about a space large enough to host his growing congregation, Ec Chajim, for the holiest day in the Jewish calendar: its own space, which opened four years ago, could not accommodate the expected crowds Since the museum had just taken down its exhibition in the Klausen Synagogue, she had an answer The clean, empty space was ready to be refilled with Jewish life

Visiting the synagogue just before Yom Kippur, Niklová said she was awed to see the building returned to its original purpose She hopes that it will continue to be used for large ser vices

“I felt like the synagogue star ted breathing again,” she says

For many in Prague’s largely secular Jewish community, Yom Kippur is the single most impor tant ser vice of the year Even Jewish families that suppressed religious practices under Communism of ten passed on the memor y of Yom Kippur, says Maxa, who founded Ec Chajim in 2019, responding

to a growing number of people who sought to explore their Jewish roots The community currently has 200 members and adds about five more ever y month “Of ten, I meet people who simply want to learn about the culture, tradition and religion of their grandparents,” says Maxa. “They say, my grandmother and grandfather were Shoah sur vivors can I come and learn more about Judaism? We of fer a wide range of activities, including, of course, regular ser vices, but also educational courses to help these people reconnect with the tradition ”

Maxa, who himself grew up in Prague with little connection to his Jewish roots, wants to revive some of the rituals that threaded through Prague’s pre-war Jewish world including a tradition of organ accompaniment in the city’s synagogues Jewish organist Ralph Selig performed during the Kol Nidre service Like many of his congregants, Maxa has a family history that inter twines with the losses of the last century His father came from Prague and survived the Holocaust He does not know if his father visited the Klausen Synagogue, but he knows it was a familiar par t of his world “It means a lot for me that the tradition was not exterminated ” n

T H E C J N M A G A Z I N E I S R E L A U N C H I N G

Stay informed, inspired, and connected—every day.

The CJN Podcast Network o ers news, analysis and commentary on Jewish issues that matter most – delivered to you daily.

Tune in. Stay connected. Discover The CJN!

Listen now on all major podcast platforms.

You were born into a Hasidic family, but your mother star ted withdrawing from that community when you were a young child What was that experience like? What was the transition point?

It was weird because we were living in a ver y Hasidic, Lubavitch area, obviously, but we were ver y much leaving that communit y or on the outs over the years I would say that we were somewhere in the middle. And this is just the theme of my life I’m an American ; I’m a Canadian I’m frum ; I’m not I’m a girl ; I’m not I’m always in the middle of so many things This was no dif ferent Looking back, I was still the most religious person at Bialik, but I felt not religious at all And it’s funny because in my life now, my girlfriend thinks I’m the most religious person she’s ever met She’s like, Well, you kiss the mezuzah For me it’s Obviously I kissed the mezuzah I’m not an animal I’m already doing gay I don’t need to play with fire any more than I have

I can empathize with that because I was on the flip side : I remember going to university and being the most religious one I wore a shirt and dress pants, because that’s what I wore that’s what I had I

“I’ ve always been a bit of a troublemaker ”

Avi Finegold talks to comedian and writer Robby Hoffman about identity, resilience, and living in between worlds.

didn’t have clothes. And then people would ask me why I was dressed for a wedding

Yeah, it’s so bizarre

Usually when I went to my friends’ houses in high school, they weren’t kosher at home but they would always have Wack y Mac or something for me Then, I think when I star ted losing my way or not being kosher anymore, it really rubbed them the wrong way I remember it was Pesach at Dawson C ollege (in Montreal) and I just had an exam an early eight o’clock exam It was over by 10 a m And I don’t know what came over me, but there was a McDonald’s acros s the street, and break fast was still being ser ved The allure when we were kids was huge all the non-Jewish kids had Happy Meals af ter school And I thought, I’d love to be happy My mother may have had meatloaf at home, which ended up being way bet ter for us long term, but I just wanted a nug get Af ter this exam, I was so depleted There was no kosher food around me I had no groceries at my apar tment I was in exam mode, star ving I’m like : McDonald’s breakfast And I broke my kosher-nes s I bought an Eg g McMuffin with bacon, with the hash browns, latkes, whatever I walked into the Dawson cafeteria and my friends who sud-

denly were the most pious people in the world when Pesach came around, not eating bread were there. I was unpeeling the wrapper and I remember my friend saying, “ You’re gonna eat that in front of me when it’s Pesach?” I said, “How many times have I come out to eat with you guys and I’ve ordered a garden salad, no dres sing, and you’re going to be high on your horse now.” And I had it, and it was unbelievable I had it ever y day for the next month, and it was just divine

The frum world, the religious world, doesn’t really have this notion of something like Rumspringa : go tr y thing s , and we know you’ll come back . It’s this straight and narrow path that, if you transgres s once, you’re done. And that’s not healthy because a boy who is told not to watch pornography because it’s the worst thing imaginable and then he sees one billboard of a woman in a bikini and he realizes that the lightning bolt hasn’t killed him yet. And so you figure, If I did that, I might as well do ever ything else Imagine if the attitude was : we don’t do these thing s ; if you think you want to do them, tr y it out for yourself and decide you can always come back

I never thought that God was mad at me I just always felt God kind of liked me for whatever reason I don’t think he was thrilled with all my decisions, but He maybe thought, Eh, what are you gonna do? My friends were really judgmental, but I never at any point thought that I was wrong If there’s a God, I feel like He’s cool with me I don’t believe that there’s a God necessarily, but I do believe there’s obviously something, there’s greaterness than us Whatever the powers- or energies-that-be are, I feel it as a protective layer But I could be wrong, you know? I just think that if you step into it, it can be nice If you don’t, that’s also cool I got good at not listening to the noise as much, and maybe that’s why I do what I’m doing

Do you consider yourself par t of the larger community of off- the -derekh people?

No Nobody wants to be defined anymore I’m kind of that way with communities. The trans community, the queer community, the Jewish community, the off-the-derekh community It’s fine if you want me in your community. I wear glasses ; there are the people with glasses There’s a community for ever ything. I’m in and not in ever ything. I’m going to break the rules

The identity thing is interesting to really wrap your head around.

People really want to claim you. I think I noticed it as you get bigger and bigger, as you do more and more, people start to want to claim you. I’m for everyone, but I really just belong to myself

You really lean into the Holocaust jokes in your comedy. What is it about the transgres sive humor that appeals to you, that works for some people and really doesn’t work for others?

I don’t know what it is I think it’s a mat ter of taste I happen to have an appetite for dark I grew up in a house and on playgrounds where we said the hardest, meanest, worst things to each other in a fight I developed a skin for it But some people don’t have the taste, they didn’t develop that skin, they don’t need it, they don’t like it There are a million reasons why it’s not somebody’s taste I don’t mind if somebody’s of fended by something; that’s their prerogative I personally don’t think being of fended is the worst thing I think being hungr y is, I think

being poor is Being of fended, to me, is not that bad I think being of fended might teach you that you feel something or you’re passionate about something I grew up in a family where there were already nine siblings I didn’t have the luxur y to be of fended I could be wrong, but I think censorship or the idea of being of fended for me feels more like a rich thing than it does a poor thing I was so comfor table living in a house with people who were so dif ferent We had similarities and we had dif ferences and we would fight like craz y And then, at the end of the day, it would be lights out, we have to go to sleep I didn’t have my own room to go to I think if you’re a rich kid, you go to your room I had to sleep with these people I really disagreed with I got comfor table being uncomfor table and I think people who are comfor table in ever y facet of their lives they’re not comfor table being uncomfor table I’m fine to be uncomfor table. Of course, I prefer being at the Rit z I prefer a nice bed, but I’m totally comfor table on the couch.

You can’t cancel your sibling .

My brother, he doesn’t love gay people. He calls me and he goes, They’ve got these agendas. I said, “You know I’m gay, right? You’re talking to a gay ” And he replies, “Well, not you. You’re my flesh and blood. I’d take a bullet for you ” What am I going to do, cut this guy of f? He’s my brother. I love him, he loves me There’s no cut ting of f in a poor family. He wouldn’t understand if I said, “Don’t call me ”

So how do you write something that is of fensive but doesn’t get too of fensive?

I don’t think of anything like that I just think about what I think is funny I’ve always been a bit of a troublemaker In school, I was a troublemaker I’ve always wanted to get a reaction of any kind I think I was blessed with that The first thing I heard from the first show I did is that I have a unique voice I heard about my voice even before I knew about it I think that is due to the fact that I sit in so many middles I’m always the window looking out, whether I’m poor looking at the rich, whether I’m Canadian in America, whether I’m a girl with a boy-ish disposition I’m always looking in, I’m always sitting on the fence n

This interview has been edited and condensed T H E C J N M A G A Z I N E I S R E L A U N C H I N G I N A P R I L 2 0 2 5

Itstarted with a ballroom, 43 executive directors of Toronto Jewish organizations, and 187 local philanthropists

This describes the first ImpactTO event, which brought together many Jewish Institutions.

Chaim Rutman, the visionar y behind this gathering last spring, had one clear goal: fostering collaboration and weaving together the Jewish organizations across the GTA

“It was like being on an escalator,” says Maidy Ehrlichster, Team Lead at ImpactTO, “for ward movement was unavoidable. There was a room full of lit-up people turning their ideas into buzzy progress. ” Patrons and community activists who had vague, undefined objectives suddenly found fertile ground to nurture those objectives into something sturdy And alive “All people passionate about ser vicing the Jewish community and inspiring the next generation of heritage builders were there. It was delicious!”

The problem ImpactTO comes to solve is one that’s familiar to most everyone across Jewish communities-exhausted money veins and ever-expanding demands. Previously padded budgets no longer cover the steady increases of the past few years

The prototypical Jewish donor is a formidable force within our communities.

Eager to help, passionate about Jewish preser vation and galvanized by a sense of mission, they’re not

afraid of writing big cheques to meet big needs. But following the complexities of each institution’s particular cash leaks is time consuming

“Before ImpactTO, many organizations within the Jewish community were working in silos, struggling with similar challenges - rising costs, inefficient marketing, and limited access to resources, ”

says Aubrey Freedman, Steering Committee Secretary of ImpactTO.

“Executive Directors faced increasing pressure to sustain operations, but there was little collaboration between institutions, which limited their ability to leverage each other’s strengths.”

That was the pre-Impact landscape. But the terrain is changing.

As a collective of 43 organizations, ranging from food banks to financial aid, from heritage building to community centers, from childcare to hospice, ImpactTO brings these separate orbits together to create a Venn diagram of more efficient and effective solutions

“Our mission is to strengthen the Jewish community by fostering collaboration, pooling resources,

and ensuring institutions can thrive,” Aubrey explains.

The nuts n ’ bolts of the operation?

• negotiating better ser vice rates

• marketing

• health and life insurance policies for community workers

• grant writing

• endowment infrastructure

• collaborative new projects

“Too many institutions expressed frustration over missing out on government grants with their low ROI to justify using already strained resources, ” says Chaim.

A new gateway for patrons looking to revitalize the historic kehillah in its modern manifestation, ImpactTO is flush with promise

Aubrey pitches the long game.

“The Jewish community thrives when we work together. We can’t afford to let institutions struggle when collective action can provide strength, efficiency, and long-term sustainability.”

It’s all about streamlining.

And Jewish continuity

“Now more than ever, it’s essential that we unify to support one another and build a stronger, more resilient community.”

The typical Jewish experience is conventionally understood to be an urban one but many Jews, by choice or circumstance, live outside of Canada’s big cities In this collection of essays and interviews, we explore what it means to live, Jewishly, in unexpected places

There are as many ways to live Jewishly as there are places Jews choose to live in

Minyan on the Mira, a 1995 documentar y about the Jewish community of Glace Bay, N.S., tells the stor y of a group of Jews who “made wine from water ” In the opening minutes, we hear about how they arrived, mainly from Russia at the turn of the twentieth centur y, not knowing the language and with lit tle to their names, and built a thriving Jewish community.

This was a stor y that repeated across Canada and, in many cases, decades later led to the same predicament: a group of residents, content with their lives and the town they grew old in, facing the reality of their community in decline, their children and grandchildren having moved to the big city, the minyan unable to sustain itself Many of these communities are gone or barely hanging on. And yet, not all Jews feel the gravitational force of city life There are some Jews who still stay in their small communities simply because they prefer it Others star t out in big cities but find themselves eventually living far from them moving for work or a par tner or out of a taste for a quieter life

In the course of making decisions about where to move to and where to stay, many of these people contend with what Judaism has to say about living in community Should a Jew move to a small town if an oppor tunity arises, even if there aren’t other Jews there? How small is too small? If you star t out in a small town, should you move to a larger one to find Jewish connections? What values come into play when thinking about these issues?

The great Jewish sage Hillel, in The Say-

ings of the Elders, writes that we should not separate ourselves from the community

This is, arguably, the conventional view in the modern world as well : Jewish life is best lived when we are together, and easiest to maintain when the critical mass you get in cities allows for robust institutions, ser vices, and synagogues

On the other hand, tradition also gives us

models of rabbis living in isolation Notably, we have the stor y of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai who, fearing for his life because of a decree against him, hid in a cave for 12 years and did nothing but study Torah and eat from a carob tree that was growing at the cave’s mouth (Sometimes, you really just need some peace and quiet to get your book finished )

A more ambitious way of framing your thinking about where to live: What do you need to grow?

Living a full Jewish life is no dif ferent than making any other significant decision about the structure of our lives Just as there is no universal answer to the question of what career to pursue or which par tner to set tle down with, there is no single way to approach how to live as a Jew Contemplating a move to a small community, or whether to stay in the one you’re already in, requires self-awareness most of all. Do you need access to kosher restaurants? An in-person daily minyan? A Jewish day school?

As Rabbi Rachel Isaacs put it to me, “If you expect a catered Kiddush ever y Shabbat, or if your solution to Shabbat morning kids’ programming is to just hire a Jewish educator, then you might not be cut out for a small community.”

Isaacs should know: in addition to being the rabbi of Congregation Beth Israel in Water ville, Maine, (total population: 15,828) and a professor of Jewish Studies at Colby College, she runs the Center for Small Town Jewish Life, an organization devoted to providing resources to Jews in isolated communities across America

A more ambitious way of framing your thinking about where to live: What do you need to grow?

Rabbi Falik Schtroks and his wife, Simie Schtroks, have been the Chabad emissaries in Surrey, B C , for the past 30 years They say that, in small communities, ever y person becomes impor tant and “ever y Jew becomes one let ter in the Torah ” As Rabbi Falik put it, there is no stagnation in human life; you either grow as a person and as a Jew or you are in decline For some people, becoming an identifiable, and even essential, par t of a social fabric the way you can in a small town but not a large city can be a tool for grow th Others will miss the social dynamics inherent to larger communities,

which can provide some momentum for individual practice, and as a result feel their Judaism atrophying.

One way to start gaining insight into these questions is realizing whether you are the type of person who takes an active role in community or your disposition is more introspective, your relationship to Judaism more personal and directed toward God and spiritual matters. Both types can thrive in small communities—it’s just a question of how you approach it. Rabbi Zolly Claman recently took a position as the rabbi of Tifereth Beth David Jerusalem in Montreal, Que., but he arrived there via Edmonton, Alta., (Jewish population: 3,515), where he served the Orthodox community. Claman appreciated living in this kind of setting.

While urban centres have their merits, he says, “What you lose out on is just that purity of the lone Jew trying to reach out to community, to spirituality, to God, to Torah, to good deeds. And to me, that’s kind of the balancing act between the two options.”

Similarly, Isaacs says that, before she moved to rural Maine, she was used to going to synagogue, getting what she needed from the shul and the community, and then going home again. When she arrived in Waterville, she was inspired by how much everyone was actively taking part and making Shabbat and holidays happen.

It’s important not to go in with illusions, however. Both the Schtrokses and Claman point out that families with children can face particular issues. If kids do not have other Jewish friends, they can start to feel isolated and uncomfortable with their Judaism.

“You can’t replace the Jewish educators and the atmosphere of Jewish education and Jewish peers,” Claman concedes. Schtroks told me that it was much, much harder to raise his kids in a small community than it was to fundraise the entire budget of his organization.

Cost is a consideration that swings in the other direction. Isaacs knows of more and more Jews who are being priced out of large urban centres and even formerly affordable suburbs and are finding themselves in small towns out of financial necessity. She sees a big part of her work as providing resources to those who do not have the finances to be big-city Jews. As she puts it: “Small town Jewish life is the frontier, not the periphery. These Jews have what to teach others who haven’t yet been hit with the affordability crisis.”

One of the most poignant parts of Minyan

on the Mira is an interview with the local Catholic priest; he observes that the Jewish community there is struggling without necessary support—the kind of bolstering that would be provided by a rabbi or cantor. His Jewish neighbours tell him that they’re getting by but, as he says, there is a difference between getting along and thriving, and that a community will be in decline if they cannot live with “the fullness of their faith.” This is particularly striking coming from a faith leader of another tradition, someone who understands the difficulties of maintaining religious observance in a small community but has the clarity of being able to witness this decline from a distance.

There is no single answer to the question of what kinds of places Jews should live in, and no single overarching value that can decide it. It very much depends on how you see and understand your Judaism. Can you see yourself as a representative of your traditions both to fellow Jews and to non-Jewish friends and neighbours? It’s easy to understand why a Chabad rabbi might frame someone living in a small community as being a representative of God and Judaism: they have a long history of being emissaries to their communities and likely assume that many other Jews can fit this model. But not everyone does.

At the very end of our conversation, Rabbi Claman pointed out that Hasidic masters had a history of occasionally going to small communities, generally incognito, and living in a private exile to see if they had what it took to be Jewish when no one else knew about it. That private trial was often what they needed to inspire them to further inspire others. The unnamed Catholic priest of Glace Bay said a very similar thing when he hoped that whatever the extant Jewish community learned from living in their own version of an exile could be put to use wherever their next stop might be.

Rabbi Moshe ha-Darshan, also known as the Kelmer Maggid, was asked if it is more praiseworthy to worship in a town that is primarily Jewish or non-Jewish. His reply, Rabbi Isaacs reminded me: if you live in a town that is primarily Jewish, you may go to synagogue because of social pressure and political gain. The Jew who maintains their commitment to mitzvot in a community that is not primarily Jewish, however, receives a greater reward because they are truly continuing to pray for the sake of God. There are opportunities to engage with your Judaism wherever you are. n

May this Chanukah spread joy and light to your family and Israel.

•

•

•

•

•

•

• Cardiovascular

•

•

• Cold and Flu

• Skin Conditions

• Weight Management

• Stress Management

• Depression/Anxiety

• Smoking Cessation

• Pediatric Health concerns

• Women’s/Men’s Health concerns and more

Berlin

• Frances Berman • Gerbrig Berman • Barbara Bernstein • William Bernstein • Lynette Beron Earl Biderman Martin Binstock Esther Birenzweig Peter Bishin

• Howard Black • Michael Black • Rachelle Blaichman • Murray E Blankstein • Kathy

Bloom • Lorraine Bloom • Pearl Bloom • Tobe Blumenstein • Derrick Blumenthal • Andrew Boardman • Howard Bogomolny • Elly Bollegraaf • David Boniwell • Marlene Borenstein • Howard Borer • Leonard Borer • James Boritz • Sylvia Bornstein • Donald & Sarah Borts Paul Braun Adam Breslin Paulette Brodey Ava Brodsky

• Avrom Brown • Herbert Brudner • Marlene Brudner • Robert Brym • Mark Bulgutch • Thomas Burko • Lori Burnett • Henri M Bybelezer • Michael Cape • Rella

Caplan Wilma Carnie Jeff Chad Mike Chapelle Morris Cherniak Peter Chodos • Aviva Cipin • Jeff Citron • Jeffrey Clayman • Katherine Cobor • Barry Coburn • Mindi Cofman • Deborah Cohen • Lori Cohen • Mark Cohen • Michael Cohen • Richie Cohen • Robert & Joyce Cohen • Robert Cohen • Ruth Cohen • Stephen Cohen • Warren Cohen • Michael Cole • Peter Collins • Tony Comper •

Judith Cooper • Richard Cooper • Sheldon Cooper • Bruria Cooperman • Debbie Cowitz • Kaila Cramer • Ron Csillag • Marcy Cuttler • Brenda Dales • Michael Dales

• Rosalie Dalfen • Doris Dalfen Caplan • Shula Dalume • Susan Dane • Bailey Daniels

Helen Daniels Matthew David Murray Davidson Allan Davis Irwin Davis Gayle De Bloeme • Roger De Freitas • Charles Deber • Joseph Deitcher • Joan Dessau • Michael Deverett • Sue Devor • Mark Diamond • Priscilla Drimmel • Daniel Drimmer Cila Drucker Rozlyn Druckman Marvin Dryer Anne Dublin Howard Dyment

Donald Echenberg • Martin Eisen • Betty Eisenstadt • Jay Eknovitz • Leon Elfassy

• David Engel • Rena Entus • Raquel Epand • Eric Epstein • Janet Eskind

• Gary Elman

• Linda Evans

• Rosalie Evans • Ronald Factor • B Joy Fai • Brian Fallick • Barbara Farber

• Marilyn Fedorenko • Anthony Feinstein • Renee Feld • Judith Feld Carr

• Jay Feldman Reah Feldman Mark Fenson Gail & Joel Fenwick Maurice Field Hillel Finestone

• Bernice Finkelstein • David Finkelstein • Marie Finkelstein

• Mildred Finkelstein

• Sandy Finkelstein • Phil Finkle • Leon Fisch • Henry Fischler

• Janice Fish Rowan Fish Bernard Fishbein Fred Fishman Sharon & Ed Fitch Marvin Flancman

• Joel & Leslie Flatt • George Fleischmann • Sheri Fleisher • Peggy Fleming • Marlene Fogel

• Marilyn Foreman • Beverley Fox • Mark & Heather Fox • Henie & Herman Frances Judith Frankfort Judy Franklin Howard Freed Howard Freedman • Laurel Friedberg • Caryn Friedman • Linda Friedman • Peter Friedmann • Harvey Frisch • Mortimer Fruchter • Lisa Fruitman • Hugh Furneaux • Shelley Gans • Miriam Gasee • Allan Gelkopf • Emmy Gershon • Fran Giddens • Brian Gilfix • Matthew Gillman • Rina Gilmore

• Brian Ginsler • Halley Girvitz • Dafna Gladman Michael Gladstone Iris Glaser Marcia Glick Shirley Glick Zana Glina

• Norman Godfrey • Rena Godfrey • Marion Gold • Nancy Gold • Ron Gold • Marlene Goldbach • Bluma Goldberg • Jason Goldberg • Lorraine Goldberg • Marsha & Jerry Goldberg Philip Goldberg Rahma Goldberg Rick Goldberg Rob Goldberg • Robert Goldberg • Sara Goldberg • Victor Goldberg • Linda Goldberger • David Goldbloom • Nancy Golden • Barbara Barak & Neil Goldenberg • Jeffrey Goldfarb • Michael Goldfarb Howie Goldfinger Lorie Goldfinger Carrol Goldhar Rita Goldkind • Helen Goldlist • Bernard Goldman • Donna Goldman • Jay Goldman • Paul Goldstein • Naomi Goltzman • Avrom Gomberg • Julius Gomolin • Magda Gondor • Abe Gonshor • Diana Goodman • Elaine Goodman • Gilda Goodman • Andrew Gordon • Ellen Gordon • Fay Gordon • Dr Randy Gordon Mpc • Sandra Goren Fabian Gorodzinsky Thomas Gorsky Eric & Enid Gossin Abe Gottesman • Dianne Gould • Allan Grachnik • Dr Harvey Gradinger • Senator J S Grafstein • David Grant • M Leon Graub • Barry Green • Bernard Green • Rochelle Green • Mark Greenberg Paul Greenberg Reesa Greenberg Reggie Greenberg Irwin Greenblatt • Dr Samuel Greenspan • Gloria Groberman • David Groskind • Ken Grove • Ken Gruber • Doris Gruneir • Paula Grunhut • Carole Gumprich • Irving Gurau Elissa Gurman Stephen Gutfreund Alan Gutmann Hymie Guttman Maxine Gutzin • Charlotte Haber • Gordon Halfin • Louise Halperin • Monda Halpern • Nelson Halpern • Linda Halpert • Linda Hannon • Joyce Harris • Riva Heft Hecht • Adele & Claude Heimann • Warren Hellen • Jonathan Hellmann • Yehudi Hendler • Bernard Herman • Marilyn Herman • Morrie Herman • Barbara Hershenhorn Lawrence Hildebrand Shainey Himal Melvyn Himel Andrea Beatriz Hirshberg • Howard Hirshhorn • Susan Hochman • Debbie Hollend • Susan Holtzman • Russell Houldin • Judy Howard • Henry & Esther Icyk • Linda Igra • Larry Iskov Robert B Issenman Shanna Jacobson Martha James Evelyn Jesin Dale Joffe • Arthur & Helen Jordan • Paul Joseph • Shirley & Norman Just • Elaine Justein • Ian Kady • Norman Kahn • Simon Kalkstein • Michael Kamien • Jake Kamin

Helene Honey Kane Gary Kapelus Lawrence Kaplan Ronald Kaplan Brian Kaplansky • Margaret Kardish • Sandra Kashton • Carol Kassel • Brian Katchan •

Henry Kates

• Marvin Kates

• Sandy Kates Minden

• Elaine Katz

• Helen Katz

• Sydney Katzman

• Lynn Kauffman

• Howard Kaufman

• Joy D Kaufman

• Marty Kelman

• Claire Sherry Kelner

• Michael Kerbel

Avanti Properties Group

Daron Financial Inc

• Sandi Kirschner

• Ernest Kirsh

• Norma Klein • Veronika Klein

• Zoe Klein

• Joel Kirsh

• Sylvia Kirsh

• Harry Klaczkowski • Francie Klein

• Sylvia Kestenberg Alan Khazam Alexander Khemlin Dora Kichler Brian Kimmel Brian Kingstone Patti Kirk

• Bernard Kleinberg • Peggy J Kleinplatz, Ph D • Marsha Klerer

• Sharon Klug

• Gerald Koffman

• Pauline Konviser

• Clifford Korman

• Jean Korman

• Jack Kornblum • Lawrence Korson

• Saul Koschitzky

• Alan Koval • Martin Koven • Philip Koven • Desre M Kramer Sarah Kranc Kathie Krashinsky Harvey Kreisman Linda Kremer Mildred Kriezman Gerald Krigstin

Economy Optical

Estate of Wilfried Umrain

Gerald & Karen Fried Family Foundation, Mrs Karen Fried

• Dan Levy • Karen Levy • Myrna Levy • Richard Levy • Steven Levy • Michael Lewis • Roslyn Lewis

• Julie Kristof • Michael Kristof • Michael Kron • Jack Kugelmass • Esther Kulman • Bernie Kuntz • Jack Kurin • Mitchell H Kursner • Dorothy Lackstone • Eric Lakien • Livia Lambrecht • Sophie Landau George Lanes Eric Lang Benjamin Langer Brian Laski Brian Lass Rebecca Laufer • Dr Steven Lax • Barbara Lazare • Dr Marvin Lean • Wendy Lee • Barbara Leibel • Sandi Leibovici • Albert Leibovitch • Peter Leighton • Molyn Leszcz • Desmond Levin • Allan Levine • Beatrice Levine Janis Lee Levine Larry Levine Lauren Levine Norman Levine Holly Levinter Barbara Levy

• Fauna & Phillip Lidsky • Susan Liebel • Archie Lieberman • Susan Lieberman • Selma Lis • David Lisbona • Dr Bluma Litner Rosenstein • Bennett Little • Madeline Lobel • Marshall Lofchick • David Louis • Sidney Lubelsky • Barry Lubotta • Gert Ludwig • Sidura Ludwig • Ian Lurie • Sherwin Lyman • Carole Machtinger Vicci Macmull Gordon Magrill Dan Malamet David Mandel Harvey Mandel Jeffrey Manly • David Manson • Arnold Marcus • Shirley Margel • Faye Markowitz • David Martz • Joel Maser

• Robert Matas • Rhoda Matlow • Ted Mayers • Myra Mechanic

• Meredith Mednick

• Ronald Medoff Sheldon Meingarten Dr Calvin Melmed Keith Meloff Pauline Menkes Susan J Merskey Lori Merson • David Mervitz • Diane Miller • Henza Miller • Leah Miller • Marvin Miller • Stephen Miller • Michael Millman • Jacqueline Mills • Harriet Millstone • Morris (Mickey) Milner • Marvin Minkoff • Gary Mintz • Max Mintzberg • Mrs Faye Minuk • Gary Mitchell • Phyllis Morais

• Ron Morgenthal

• Sandra Morris

• John Morrissey

• Ezra Moses

• Dan Moskovitz

• Dr Seymour Moskovitz

• Milt Moskowitz

• Brian Mozessohn

• Bill Muller

• Jack Muskat

• Martin Nadler

• Joseph Naiman

• Gloria Naken

Linda (Laya) Feldman Fund, Mrs Laya Linda Feldman

Lodestone Investments Limited

Lola Rasminsky Fund, Toronto Foundation

London Jewish Federation

Malca & Louis Drazin Family Fund, Mr. Louis Drazin

• Dr Paul Nasielski

• Greg Newman

• Cecile Nightingale

• Charlotte Nowack

• Mark Nusinoff

• Jeremy Nusinowitz

• Sandra Offenheim

• Mark Oppenheim

• Bernard Ornstein

• Stephen & Betty Ornstein

• Mary Orzech Raymond Oster Barbara Ovadia Simone Oziel Albert Page Barbara Palter Michael Pascoe Sharon Pearlstein

• Dr Gerald Pearson

• Ronnie Peck

• Bernice Penciner

• Deanna Peranson

• Gerry Pernica • Dr Bruce Peter Elman

• Austin Phillips

• Sheila Pinkus • Joel Pinsky • Gary Polan

• Nina Politzer Barry Pollock Hyla & Gerry Prenick Barry Presement Gustave S Presser Robert Presser Leslie Priemer

• Arthur Propst

• Wendy Ptack-Wechsler

• Gabriel Pulver

• Alberto Quiroz

• Eva Raby

• Rochelle Rajchgot

• Barbara Raphael

• William & Netty Rappaport

• Stephen Rapps

Morris Norman Professional Corporation

Paul Bronfman Family Foundation

Redrock Inc.

• Marsha Raubvogel

• David Rauchwerger

• Raymond Rawlings

• Stuart Rechnitzer

• Reuben & Beverly Redlick

• Allan Rein

• Neil Reine

• Sam Reitman

• Debora Resnick

• Edward Rice

• Marlene Richardson

• Lisa

R

Le w i s Rose

• Barry Rosen

• David Rosenberg

• Dr Frank Rosenberg

• David Rosenblatt

• Harold Rosenfeld

• Richard Wayne Rosenman

• Gerald Rosenstein

• Estelle Rosenthal

• Judith Ross

• Tammy Ross Lorraine Rotbard Alice Roth Millard Roth Sherryn Roth Steve Roth Susan Roth Carol Rothbart

• Jack Rothenberg

• Danny Rother • Laurel Rothman • Gella Rothstein

• Martin & Marsha Rothstein

• Roslyn Rotin • Gerry Rowan • Anthony Rubin • Benjamin Rubin

• Robert Rubinstein

• Robert Ruderman Susan Rudnick Zil Rumack Perry Rush Stanley Sager Alan Saipe Orna Salamon George Saltzberg • Esther Salve-Hindel • Cynthia Samu • Gary Samuel • Shirley Samuels • Alan Sandler • Ian Sandler • Melvyn Sandler • Kerop Sargsyan • Mark & Naomi Satok • Kenneth Saul • Hershie Schachter • Beverly Schaeffer • Lionel Schipper • Theodore Schipper • Bernie Schneider •

D e b ra & St e p

S

S

Richard & Sheila Rodney Family Fund, Jewish Foundation of Greater Toronto Scout Holdings

Seyglor Consultants Inc

Susan & Aron Lieberman & Family Foundation, Mr. Lorne Lieberman

The Azrieli Foundation

The Dan-Hytman Family Foundation

The Ira Gluskin & Maxine Granovsky Gluskin Charitable Foundation

The Jamlet Foundation, Mr. Edward Lohner

The Kelman Charitable Foundation

• Pacey Sugar • Etta Sugarman

• Leon Szyfer • Cheryl Tallan

• Marilyn Sunshine • Leonard Sussman • Miriam Swadron

n e i d m an Marcia Schnoor Abe Schwartz Gerald Schwartz Seymour Schwartz Mark Segall Carol Seidman • Stuart Selby • Mary Seldon • David Seligman • Stan Shabason • Maxine Shaffer • Michael Shain • Brenda Shamash • Irene Shanfield • Shelly Shapero • Zipora Shapiro • Ann Sharpe • Ricki Sharpe Susan Sharpe Allan Sheff Helen Sheffman Noreen Shelson Susan Sheps Kathy Sheres • Francine Sherman • Victor Shields • Stanley Shier • Gary Shiff • Randy Shiff • Diane & Gary Shiffman • Chull-Ho Shin • Joanna Shore • Robert Shour • Phyllis Shragge • Suzanne Shuchat • Elinor Shulman Rhona Shulman Thelma Shulman Alta & Ken Sigesmund Marvin Silbert Dr Brian Silver • Norman Silver • Paula Silver • Rochelle Silverberg • Sheldon Silverman • Howard Simmons • Charles Simon • Evelyn Simon • Sueann Singer • Rene Skurka • Dr Leonard Slepchik • Ronald Sluser • Lynne Smith • Mitchel Smith • Sheila Smolkin • Bernard Snitman • Martin Sole • Lorne Solish • Maureen Solomon • Estelle Solursh • Hana Sommers • Evan Sone • Anya Sorkin • Gertrude Speigel • Hope Springman Alan Stackle Laura Stambler Gordon Starkman Lisa Starkman Niki Starkman Peter Stein • Leesa Steinberg • Joseph Steiner • Sandra Steiner • Joel Steinman • Carole Sterling • Arthur Stern • Dr Donna Stern • Michael Stern • Marion Sternbach • Nicola Stevens • Kenneth Stewart • Marjorie Stober Roberto Stopnicki Alex Strasser Louis Strauss Richard Stren Leo Strub Jeffrey Stutz

• Stephen Tanny

• Harvey Taraday • Irwin Tauben • Jerome Teitel

• Joseph Telch William Tencer Aaron Tiger Gabrielle Tiven Ruth Toplitsky Marshall Train Rosalyn Train Ed Treister • Jeffrey Trossman • Karen Truster • Adrienne Turk • Alina Turk • Harry Turk • Nanci Turk • Paul Tushinski • Suzy Tylman

• Peter Usher • Richard Vineberg • Elaine Vininsky • Leonard E Vis • Stan Waese • Fred Wagman • Hazela Wainberg • Larry Wainberg • Jay & Debbie Waks • Sam Waldman • Sheila Walker • Marla Waltman • Ruth Waltman • Susan Waserman • Mavis Wasserberger • Stanley Wax Mary Weingarden Sheldon Weingarten Larry Weinrib Gilbert Weinstock Joseph Weiser

• Henry Wellisch • Sol Werb • Adam Wetstein • Marc Wilchesky • Jerry Willer • Karen Willinsky • Edward Wiltzer • Mark Wiltzer • Frances Winer • Charles Winograd • Anita Winston • B Winston • Ralph Wintrob Donna Wise Dr Sheldon Wise Marlene Wiseman Michael Wiseman Suzanne Witkin

• Linda Wolfe

• Debbie Wolgelerenter

• Harold & Shelley Wolkin

• Irwin Wortsman • Jonathan Wyman

• Miriam Wyman • Jack Wynberg • Leo Wynberg • Mark Yaffe • Jan Yazer

• Helen Yerzy • David Zackon Cecile Zaifman Joseph Zalter Ari Zaretsky Evan Zaretsky Martin Zeidenberg

• S h

The Monica & Barry Shapiro Fund, Mr Barry Shapiro

The Sue Carol Isaacson Fund, Mrs. Sue Carol Isaacson

The Tamara & Philip Greenberg Family Fund, Mr Philip Greenberg

Total Procurement Solutions Inc

Workman’s Circle Ontario District

Zwiebel & Associates

In the book Conversations with Isaac Bashevis Singer, the acclaimed Yiddish author tells the stor y of a Jewish man who visits the cit y of Vilna (Lithuania, not Alber ta) Upon returning from his trip, the man says to his friend, “The Jews of Vilna are remarkable!”

The friend asks, “What’s so remarkable?”

The man answers, “I saw a Jew in Vilna who schemed all day long about how to make money I saw a Jew waving the red flag and calling for revolution. I saw a Jew who was running af ter ever y woman I saw a Jew who was an ascetic. I saw a Jew who preached religion all the time ”

His friend asks, “Why are you are so surprised? Vilna is a big city There are many types of Jews ”

“No,” says the first man, “it was all the same Jew ”

Though amusing, Singer’s purpose in telling the tale was to of fer insight He noted that the Jew is so restless he is almost ever ything at once, at tributing this restlessness to a par ticular kind of intelligence that creates an energ y and manifests as a need to always be doing, planning, or pursuing with singular passion some abstract idea While a generalization, it doesn’t feel

untrue or at least it contains enough truth to make the joke work.

To pile commentar y upon commentar y (Talmudically, if you wish) , I would note that even as a collective, Jews are so restless they’re almost ever ything at once: the variety of language, lifestyle, class, ideolog y, and religiosity among Jewish people is such that it can feel reductionist to make any generalization about our co-religionists.

Singer’s stor y, then, works as an obser vation even without the punchline Indeed, by ruining the joke and turning it into a prompt for commenting broadly about the stereotype that of the anxious, changeable, wandering Jew we perhaps fulfill Singer’s obser vation: that the Jew is so restless, so unset tled, they are wont to become almost ever ything at once, whether by circumstance, situation, necessity, or pilpulistic contrarianism

So, we contain multitudes Are multitudinous containing ever ything, wandering endlessly, doing, planning, pursuing, assuming the stance of an exiled ancestor, making a personality out of histor y, living the character, and feeling it like fate whether gathered through our genes or through our memes

But multitudes aside, the stereotypes per-

sist and are not always without merit The Jews are an urban people. It’s been said, there are quotes I can find them, I can have a computer find them for you. There are reasons given, there are reasons disputed. Jews are an urban people because we couldn’t own land, because we couldn’t join guilds. We’re an urban people because many excelled in trade, finance, and intellectual pursuits, all of which are central to urban environments We’re an urban people for safety, to remain close to the centres of civilization to influence leadership so that we may live under a tolerant government I have the sources, I’ll dig them up There is truth in common ut terances, there is contentiousness in them as well We are all inevitably products of histor y and historiography We are born into circumstances, but also born into par ticular tellings of those circumstances Both shape our perception, then our actions and contributions

Though the urban stereotype seems true enough, at least from the Haskalah (Enlightenment) on, through immigration, assimilation, and modernization there isn’t a lot going on in the other direction No one says, “The Jews are a rural people ” Because not so much, not really And again, we have the

why, and can seek out and verif y and find all the evidence Because it’s harder to run a synagogue in nor thern Quebec than it is in Westmount Because there’s no market for kosher meat in Happy Valley- Goose Bay, N L Because the institutions, organizations, and community that make up Jewish life are more difficult to maintain without a critical mass of Jews

Now, if modernization, globalization, and/ or catastrophe were to render these enduring organizations, institutions, and holy relics extinct, it would strike much of the public as sad As when faced with the loss of a species, we resist, we conser ve whether for sentiment, or the fear and knowledge that that which is lost contains irretrievable value But there is arguably more on the line with the loss of community than just ar tifacts, ways of being, ways of cooking, historical knowledge, jokes, and sometimes wisdom On the impor tance of community, Singer, in the same book paraphrased earlier, writes the following:

“The Ten Commandments are commandments against human nature Many people would like to steal if they knew that they could do it without being punished But Moses came and he said that if humanity wants to exist it has to follow cer tain rules no mat ter how difficult they are. I would say that even to this day we have not yet convinced ourselves that people can make such decisions and keep them Even when they make them, they can only keep them if they make them as a collective If people live together like the Jews in the ghet tos they keep to their decisions Why ? Because one guards the other.”

Not only is community essential to civilization keeping us on guard against our human nature but its dailiness and regular rhythms are necessar y to an individual’s ability to identif y with the collective and thereby feel they have a place in the world In turn, through personal identity founded in community, the collective is reinforced and so exists, or even thrives Tradition lives as long as you practise it

We rural Jews, then without a bustling community, a critical mass, or even a poorly at tended synagogue what are we doing out here? In the sticks, in the boonies, making mat zah by hand and leaving Seinfeld on a loop? Containing multitudes? Writing restless essays on ever ything at once? Mangling tradition and identif ying with commercial versions of a histor y known in par t through

cheap data and Temu ads? Anthropomorphic hamantashen doormats from $9! Jewdolph the Blue -Nosed Reindeer tote bags from $4! Polyester sweatshir ts imploring the wearer, or reader of the wearer, to “Imagine if your phone was at 10% but lasted eight days? Now you understand Hanukkah!” from only $12!

We’re doing what in the woods? Well, whatever We wandered out here Or were led by family, friends, or men we met online The same thing that directs the rest of the rootless, restless modern souls who find themselves simultaneously inside and outside of culture And though detachment, even in a bucolic set ting, might be an absolute tell of our modernity as Saul Bellow says, “To be modern is to be mobile, forever en route with few local at tachments anywhere,

We are born into circumstances, but also born into particular tellings of those circumstances.

cosmopolitan, not par ticularly disturbed to be an outsider in temporar y quar ters” in a sense, we’ve been practising that mobility, that outsider status, that potential for a cosmopolitan disposition, since before we had the consciousness to know it

Thus, due to circumstance and personal quirks, we are not all fated to live tradition, to guard against deviance, to know the blessing on a major (Jewdolph) purchase

There is no use in lamenting alienation, exile, or estrangement par ticularly when that estrangement fits so well within an obser ved and somewhat yearned af ter collective identity of restless wanderers because though there is living tradition and historical connection in community, there is intrigue in the individual As Singer says, look to the “human ocean” that surrounds you “where stories and novelties flow by the millions ”

Maybe we, the rural Jews, the feral, far-flung untraditional Jews, can accept ourselves and our brand of restlessness

through that lens of novelty and curiosity that Singer identifies Or else we forge ahead because time moves in only one direction and find ourselves drif ting through modernity mapping out new identities online And for now, though cer tainly not forever, it might look like a backwards hat and a TikTok-trend inflected voice saying, “I’m a rural Jew of course I whit tled my mezuzah out of drif twood” played over a billion small screens, making reality out of hyperreality, hyperstitiously forming an identity on the historical realities and inventions of a people drenched in time and, say, more specifically, the 1970s when their grandmother got divorced, lef t Montreal, and went adventuring And this new mush of a person might say they consider themselves a hyphenated Jew As in, a “I’m a Rural-Jew ”

“I’m a Rural-Jew of course I grew up in isolated Canadian communities with a family who wanted to give me a sense of Jewishness, which, without the input of traditional rigour, amounted to ver y cute, highly irregular, idiosyncratic practices determined by whim ”

“I’m a Rural-Jew of course we did the fun holidays, the dress up holidays, the good food holidays. Mostly Hanukkah.”

“I’m a Rural-Jew of course Jewish summer camp made me feel like a voyeur peering in a bedroom window, watching the real Jews make their collective histor y while doubting my own Jewishness and internally arguing myself to sleep.”

“I’m a Rural-Jew of course I learned the Shema on YouTube.”

And what would Singer, adopted angel of the introduction, say about these new versions of an old people breaking with tradition, forming new tradition, reviving ancient tradition, and learning about themselves, each other, and the burgeoning multitudinous collectives of online life? Perhaps he would shrug, as he was accustomed to do, or else he would say, as he’s said once before, that “the more you see what other people do, the more you learn about yourself ”

We can hope

We can hope to learn, we can hope that wisdom isn’t relegated to the past, we can hope that restlessness yields innovation, invention, and creativity And we can know that whether urban or rural, religious or secular, stories of the individual enter tain us, make us smile, add depth to our days, and grist to the mill And that, luckily, stories are something we’ll never run out of n

our support of Israel's right to exist as a democratic and Jewish state, existing peacefully and securely alongside its neighbours.

On December 25th, as the sun sets, Jewish communities in Canada and around the world will gather to celebrate Hanukkah, the Festival of Lights. As we light the Hanukkah candles, we extend our warmest wishes for a joyous holiday. Hanukkah is a celebration of light overcoming darkness, hope prevailing through adversity, and the strength of the Jewish people, whose resilience continues to inspire us all.

May the glow of the menorah inspire all of us to continue working toward a brighter, more inclusive future. Let us carry the lessons of Hanukkah with us throughout the coming year celebrating unity, fostering understanding, and always reaching toward the light.

As we celebrate Hanukkah, we reaffirm our commitment to the values of freedom, respect, and dignity for Jewish Canadians, and our dedication to combating antisemitism both here at home and abroad We also stand firm in

abroad.

Wishing you and your loved ones a blessed and prosperous Hanukkah.

Chag Hanukkah Sameach!

Le 25 décembre, au coucher du soleil, les communautés juives du Canada et du monde entier se réuniront pour célébrer Hanoukka, la fête des lumières. En allumant les bougies de Hanoukka, nous vous adressons nos vœux les plus chaleureux pour une fête joyeuse. Hanoukka est une célébration de la lumière surmontant l'obscurité, de l'espoir prévalant sur l'adversité et de la force du peuple juif, dont la résilience continue de nous inspirer tous.

fermement le droit d'Israël à exister en tant qu'État démocratique et juif, dans la paix et la sécurité, aux côtés de ses voisins.

Puisse la lueur de la ménorah nous inspirer tous pour continuer à œuvrer en faveur d'un avenir plus lumineux et plus inclusif. Portons les enseignements de Hanoukka avec nous tout au long de l'année à venir : célébrons l'unité, encourageons la compréhension et tendons toujours vers la lumière.

Nous vous souhaitons, à vous et à vos proches, une Hanoukka bénie et prospère.

En célébrant Hanoukka, nous réaffirmons notre engagement en faveur des valeurs de liberté, de respect et de dignité des Canadiens juifs, ainsi que notre détermination ntre l'antisémitisme, ous qu'à l'étranger. enons également

PRESENTED BY / PRÉSENTÉ PAR

PRÉSENTÉ PAR à lutter contre tant chez nous qu'à Nous soutenons

Chag Hanukkah Sameach!

Parm Bains, M.P. · Yvan Baker, M.P. · Hon. Terry Beech, M.P. · Hon. Bill Blair, M.P. · Ben Carr, M.P. ger, M P · Shaun Chen, M P · Paul Chiang, M P · Michael Coteau, M P · Julie Dabrusin, M P Terry Duguid, M P · Julie Dzerowicz, M P · Ali Ehsassi, M P · Hon Mona Fortier, M P and, M P Hon Hedy Fry, M P Anna Gainey, M P Hon Karina Gould, M P Hon Steven Guilbeault, M P .P. Ken Hardie, M.P. Anthony Housefather, M.P. Hon. Marci Ien, M.P. Hon. Helena Jaczek, M.P. · Arielle Kayabaga, M P · Hon Kamal Khera, M P · Hon David McGuinty, M P · Hon John McKay, M P cino, M P Wilson Miao, M P · Hon Joyce Murray, M P · Yasir Naqvi, M P · Hon Mary Ng, M P med, M P Jennifer O'Connell, M P Hon Rob Oliphant, M P Hon Carla Qualtrough, M P P Hon Ruby Sahota, M P Hon Harjit S Sajjan, M P Hon Ya'ara Saks, M P Randeep Sarai, M P M.P. · Ryan Turnbull, M.P. · Tony Van Bynen, M.P. · Hon. Dan Vandal, M.P. · Anita Vandenbeld, M.P. P · Patrick Weiler, M P · Hon Jonathan Wilkinson, M P · Jean Yip, M P · Sameer Zuberi, M P

Shafqat Ali, M.P. · Parm Bains, M.P. · Yvan M.P. · Hon. Terry M.P. · Hon. Bill M.P. · Ben Carr, M.P. Hon. Bardish Chagger, M.P. · Shaun Chen, M.P. · Paul M.P. · Michael Coteau, M.P. · Julie Dabrusin, M.P. Anju Dhillon, M.P. M.P. · Julie Dzerowicz, M.P. · Ali Ehsassi, M.P. · Hon. Mona Fortier, M.P. Hon. Chrystia Freeland, M.P. · Hon. M.P. · Anna M.P. · Hon. Karina M.P. · Hon. Steven M.P. Brendan Hanley, M.P. · Ken M.P. · M.P. · Hon. Marci M.P. · Hon. Helena M.P. Majid Jowhari, M.P. · Arielle M.P. · Hon. Kamal M.P. · Hon. David McGuinty, M.P. · Hon. John McKay, M.P. Hon. Marco Mendicino, M.P. Wilson Miao, M.P. · Hon. M.P. · Yasir M.P. · Hon. M.P. Taleeb Noormohamed, M.P. · Jennifer M.P. · Hon. Rob M.P. · Hon. Carla M.P. Leah Taylor Roy, M.P. · Hon. M.P. · Hon. S. M.P. · Hon. Ya'ara M.P. · M.P. Francesco Sorbara, M.P. · Ryan M.P. · Tony Van Bynen, M.P. · Hon. Dan M.P. · Anita M.P. Hon. Arif Virani, M.P. · Patrick M.P. · Hon. Jonathan M.P. · Jean M.P. · Sameer M.P.

2022-2026 City of Vaughan

Members of Council

First row, left to right: Gila Martow, Ward 5 Councillor; Chris Ainsworth, Ward 4 Councillor; Rosanna DeFrancesca, Ward 3 Councillor; Adriano Volpentesta, Ward 2 Councillor; Marilyn lafrate, Ward 1 Councillor

Second row, left to right: Gino Rosati, Local and Regional Councillor; Linda Jackson, Deputy Mayor, Local and Regional Councillor; Steven Del Duca, Mayor of Vaughan; Mario Ferri, Local and Regional Councillor; Mario G Racco, Local and Regional Councillor

Menorah Lighting Ceremony

Mayor Steven Del Duca and Members of Council wish you and your family a wonderful Chanukah Chag Chanukah Sameach! Mon , Dec 30 3:30 p.m. Vaughan City Hall 2141 Major Mackenzie Dr FREE KOSHER REFRESHMENTS FREE REGISTRATION vaughan ca/festive

Laura Smith MPP/Députée – Thor nhill

Robin Martin MPP/Députée – Eglinton–Lawrence

Andrea

MPP/Députée – Barrie –Innis l

Stephen

MPP/Député – King–Vaughan

Michael

MPP/Député – Aurora–Oak Ridges–Richmond Hill

Su s a n i s t h e n a m e o n my b i r t h ce r ti f i -

c ate, b u t I n eve r rea l ly l i ke d i t I was o n a B u d d h i s t ret reat i n my l ate 3 0 s w h e n

a tea ch e r s a i d, “ Yo u d o n’t l o o k l i ke a S u -

s a n I t’s n ot t h e rig h t n a m e fo r yo u D o yo u h ave a n ot h e r n a m e? ” I to l d h i m t h at I h a d

t h i s H eb rew n a m e t h at I h a d n eve r go n e by, eve n w h e n I l ive d i n I s ra el H e t h o ug h t

I s h o u l d t r y i t

Weeks later, at a yoga retreat, I realized there were four other Susans ; it seemed like a good time to tr y something dif ferent Shulamit felt like a bit of an outdated name, but my Israeli cousin sug gested that I go by Shuli. For the last 17 years, that’s the name that ever yone has known me by I don’t even respond when I hear someone call out my previous name I spent my childhood in Etobicoke, Ont ; we were one of two Jewish families in the neighbourhood I remember leaving class to sit in the librar y, along with my siblings and the kids from that other family, when the class recited the Lord’s Prayer, talked about the Bible, and drew pictures of Jesus My mother made sure we had a strong sense of Jewish identity, keeping us involved in the local Reform synagogue and sending us to Zionist summer camps We’d of ten spend Jewish holidays with my grandparents in Hamilton, Ont , and we all had our bar and bat mit zvahs at the Solel Congregation in Mississauga, Ont

The first full-time job I got of fered as a vet was in 1997 at the most Jewish intersection of Toronto, Ont : Bathurst Street and Lawrence Avenue I was all set to move back when the job fell through and I ended up going out to Grand Forks, B C , to fill a maternity leave Af ter a summer being the sole vet in a small town, I decided to move to Vancouver, B C , to work in a busy emergency clinic Although I hadn’t planned

It’s been a theme of my life to want to fit in and at the same time to be a bit different.

It’s been a theme of my life to want to fit in and at the same time to be a bit different When I had friends going to the Hebrew University of Jerusalem for a year, I decided to go to Tel Aviv University instead I ended up living on a kibbutz for the next few years, making aliyah, and doing my army ser vice Eventually, I came back to study and enter veterinary school at the University of Guelph

to make a move to the West Coast, I ended up loving the lifestyle and stayed out west, pursuing my interest in holistic modalities to treat animals

forest and mountains and lake

We’re slowly finding that there are Jews out here and a lovely, albeit small, Jewish community in Nelson, B C , which we joined for a Yom Kippur ser vice on the beach of Kootenay Lake

Still, for years, I toyed with the idea of moving outside of the city to be closer to nature, and to have more space to do things like garden and have more animals In 2022, my daughter and I found a home in Slocan, B C I was at tracted to the beauty of the valley Af ter we arrived, I realized that, when my daughter said she wanted a horse, we could actually have a horse! Life is a bit dif ferent here, surrounded by

Wearing a Star of David is something I had never done With the current climate of antisemitism, I felt a private need for something special and simple that could lay close to my hear t, day and night I had an ar tisan craft one, inspired by a simple military-issue one that I had carried in my pocket Even here in nor thern Nova Scotia, there’s enough antisemitism that I found myself hiding it under my clothes I decided to take it off and put it in a special little box on my dresser

My parents grew up in the boroughs of New York City They were poor, but valuing education got them both to college My father spent

his academic career at Colgate University in central New York state; we were the only family where both parents were Jewish We kept our ethnicity hidden Colgate had a Hillel group, and a couple of students gave me Hebrew lessons and introduced me to some of the traditions I learned to sew on a sewing machine when I was four and was drawn to vivid colour and heavy embroidery I would fantasize that I lived in Poland, where my paternal grandmother was born; my aesthetic was shaped by the ethnic crafts of that culture

When I was 17 years old, my family moved to Israel for the year: my father was pursuing

a research program studying the kibbutz and moshav An ear problem prevented him from flying, so we took a boat from New York City to Israel I remember arriving in Haifa and feeling this enormous sense of relief surrounded by Jews; it was a wonder ful feeling of not having to hide who I was Af ter returning from Israel in 1968, I took a three-week trip to Prince Edward Island to visit a friend who moved there to avoid the Vietnam War draf t I was always drawn to remote rural locations, so many years later after several false star ts and several degrees, af ter designing transparent Western clothing

that was featured on the cover of Women’s Wear Daily and teaching ar t at Parsons School of Design when finances forced me to consider relocation, the Maritimes came to mind I drove up to explore possibilities and came to a small village with a health food store, its own subversive bookstore, and plans for an ar t centre I was smitten, and began to plan my home and studio and to navigate the immigration process

I knew of no other Jewish people in this community, however At one point, I made a friend who attended a synagogue in Halifax, N S which is two hours away I attended a few

times with the hope that I could fit in I didn’t Feeling my roots deeply, I continued to search for accessible connections and discovered a book: Sacred Therapy by Estelle Frankel, an Or thodox Jewish scholar and psychotherapist whose writing drew inspiration from Kabbalah This book saved my life I’ve read it three times, copied vast por tions into my own notebooks, re-read passages; this is the teacher I was seeking I’ve contacted her and we’ve had a number of sessions, and I also update her on my ar twork, which is influenced by her writing My ar t (I am currently represented by the Galerie

Rober tson Arès in Montreal) is intended to take me and the viewer upward, to higher realms, and downward, to the most basic and rudimentary levels of being It’s an attempt to convey the creation myth of breaking apar t to recreate, lights shattering and scattering to be gathered and contained once more

The pulse of the sea also embodies this gathering and scattering I wanted to live near the water, the tide, to take those rhythms into the deepest par ts of my being Though my beautiful Star of David sits waiting in its box on my dresser, I am content in my private and precious Jewishness on this remote shore n

Iwas born in Jerusalem but grew up in midtown Toronto, Ont., with secular parents my dad is Israeli and mom is from Winnipeg, Man. who gave me a lot of freedom to roam around the city on my BMX bike This led me to the riding scene, and I ended up meeting an Indigenous mentor, another BMX-er and an entrepreneur tool and die maker He gave me a lot of suppor t, and opened my eyes to the existence of Indigenous people in Canada, and lit the spark that led me to one day work for them

A few years later, when I was 26, I was looking for work as a teacher; jobs in the nor th were available immediately and paid well There was a major street dog problem at the time I noticed one chasing cars up and down the main drag, a black husk y mix that I ended up adopting On walks, she was always pulling my arm of f until somebody gave me a harnes s ; I got her to star t drag ging logs to slow her down Soon enough, I realized I would like a dog

team Looking back, it was pret t y meshuggeneh, but I was get ting a serious taste for mushing adventures and winter camping at some pret t y frigid temperatures.

I met my wife, Christine, as a spectator at a dog - sled race at the Inuvik Spring Carnival in 2011 She seemed ver y interested in the dog teams so I introduced myself and invited her for a dog - sled ride We quickly hit it of f, and we eventually adopted eight more huskies Now we have a six-year-old daughter, Ruthie

I learned so much about dog mushing from the Indigenous elders in Inuvik, N W T They insisted that the dogs had to have the best food, the best bedding, the best equipment, and the best training If we wanted to win races, we had to train them consistently day in day out, tr y not to run them in -30 weather or colder, and always keep the dogs wanting more Just like people, dogs will do fantastic things if they feel good about what they’re doing

My mushing and racing days are over now ; Christine and I are focusing on parenthood But I still enjoy playing outside with our retired dogs ever y day af ter supper

Christine’s family had also worked with sled dogs for generations ; her back ground is half Inuit and half European Af ter our daughter was born, we star ted talking more about Judaism, wondering what would be involved in taking on more obser vance During the pandemic, we connected with a rabbi in Vancouver, B C , who was suppor tive of the conversion proces s, fully knowing the challenges we face living in the Nor thwest Territories The rabbi we were working with for an Or thodox conversion unfor tunately moved on from his job, and we’re now pursuing it with a C onser vative congregation instead

We obser ve Shabbat in a fully traditional fashion, and consider it a bles sing We’ve got timers on the lights, food in the slow cooker, and savour a day in which we don’t work, drive, or shlep We get kosher chicken and beef shipped in from Edmonton, Alta My wife appreciates that the chicken is cheaper, and bet ter qualit y than what you get here, without all the kishkes I love studying Torah, especially on Shabbat, and I’m engros sed with the writings of rabbis from the Middle A ges : Rabbi Saadia Gaon, Rashi, Maimonides, Nachmanides, and Abarbanel they all had enormous minds.

It’s been hear twarming to see my daughter learn a lit tle Hebrew, especially through the brachot Those blessings are bet ter than any mindfulness app to help you slow down and be grateful I love discussing Torah with Ruthie, and it brings us great nachas when she enthusiastically wants to discuss the moral and legal quandaries in Mishpatim or Bava Kamma Of course, I make some adjustments: “What would you do if your friend asked you to watch her teddy bear and then it got lost?” “Who should pay the vet bills if we were watching our friend’s dog and one of our sled dogs bites it?”

Judaism has also made me more inquisitive : we went into her conversion proces s with a lot of questions, and we’ve done a lot of listening Practising far away from a Jewish communit y is unique, insofar as we have our own lit tle bubble On one hand, we’ve created a space for our Jewish values and traditions to grow and develop as a family, and on the other, I know that we can bring a lit tle light into all aspects of our current life here in the Arctic n

Af te r f ive yea r s o f l ivi ng as a m a rri e d c o u p l e i n To ro n to, O n t , my h u s b a n d

a n d I wo n d e re d i f we s h o u l d go o n a n a dve n tu re toget h e r a n d t r y s o m et h i ng n ew

A n d t h e re i t was : a n ewsp a p e r a d fo r e d u -

c ati o n a l tea ch i ng o p p o r tu n i ti e s a c ro s s t h e No r t h we s t Te rri to ri e s We t h o ug h t we wo u l d d o i t fo r t wo yea r s I t e n d e d u p l as ti ng fo u r d e c a d e s

I had Jewish relatives on my father’s side but my mother’s father was an Anglican minister, so that ended up being my parent’s way of life Judaism, though, was a par t of my heritage I felt connected to ; when I met a Jewish man in Miami Beach, Fla , who became my husband, it was also par t of accepting that connection for myself. We married at a Unitarian church in Ot tawa, Ont , but we gravitated to the Oraynu Congregation in Toronto, as it felt comfor table and right to me to have a formal, secular-humanist conversion

The jobs in N.W.T. brought us to a communit y of about 1,200, close to the Arctic Circle. We were amazed by the landscape when we first arrived in Pangnir tung My husband had never seen a mountain, and here we were living in a f jord at the base of a mile -high mountain range directly on the Arctic Ocean We stayed in Pangnir tung for four years ; our first child was born there. By the late 1980s, we had moved t wice more, spending t wo years in Gjoa Haven, Nunavut, and three in Cambridge Bay, Nunavut, and had t wo more kids In the late 1980s we moved to what was then called Frobisher Bay : in 1999, when Nunavut became its own territor y, the name was changed to Iqaluit as a par t of Inuit reclamation of place names

We found Jewish friends to celebrate holidays with in all the communities we lived in, but we also developed a tradition of throwing a big annual Hanukkah par ty, to give ever yone a taste of something Jewish One year, our kids invited so many friends many of whom were Inuit that we had over 100 people in our home

Oraynu, in Toronto, was where our children all had bar and bat mit zvahs, although we also did have a b’nai mit zvah in Iqaluit for our twins The hotel where we held it was