32 minute read

The Future of the Past An expert panel discusses improvements to the teaching of American his tory

DEBATES OVER THE

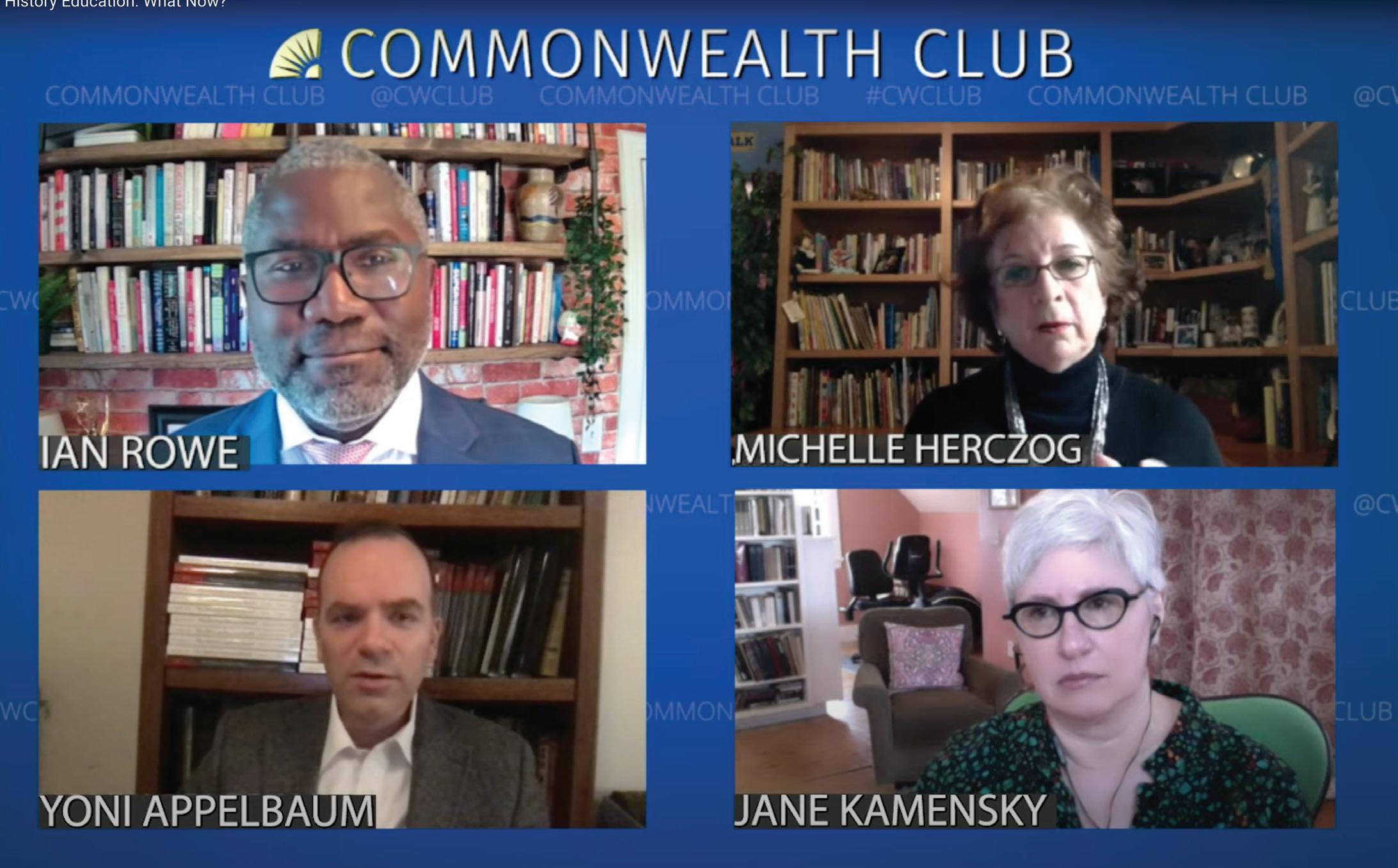

best ways to teach American history—what to teach, what to emphasize, how to communicate it—grew even more pronounced after a year of a pandemic, focus on racial justice, and the final year of the Trump administration. We assembled an expert panel to discuss the issues at hand, particularly for K–12 students. From the January 6, 2021, online program “The Future of American History Education: What Now?” JANE KAMENSKY, Jonathan Trumbull Professor of American History at Harvard University IAN ROWE, Resident Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute MICHELLE HERCZOG, History-Social Science, Coordinator III for the Los Angeles County Office of Education YONI APPELBAUM, Senior Editor of The Atlantic—Moderator YONI APPELBAUM: Today, I’m joining you from Washington, D.C., and there probably couldn’t be a better place or time to discuss these questions. As I speak to you, straight down 16th Street there is a rally at the White House. Congress will be sitting at one o’clock to count the electoral votes. Meanwhile, election returns are still rolling in from the state of Georgia, where it appears that the pastor of Martin Luther King’s old church has just won election to the United States Senate, and Democrats appear poised to, with 50 seats, control the Senate going forward.

These are historic times, and we’re not quite sure what history will make of them, but it’s a good time for all of us to meet today and think about what we make of history. There is anger in the streets here in D.C., and there is passion and excitement and engagement. Among the many questions that we ask today are, What does this mean for the education of America’s students—particularly around history and the foundational principles of our democracy?

Over the past year, the president has pushed an effort around patriotic education and American ideals. In part, in the pushback to The New York Times’ 1619 Project but also well beyond that, he launched a 1776 Commission to promote study of America’s founding principles, as he sees them. Today’s discussion will focus on these issues and the road ahead for American history education. I want to begin by turning to Professor Kamensky, and asking her thoughts on how to think about these issues, particularly at this moment. JANE KAMENSKY: I come from higher ed, and a pretty rarefied corner of higher ed at that. I teach the American Revolution at Harvard, offering the first lecture course on the subject in decades, which is a story in itself. In that class, I aim to share cuttingedge scholarship, much of it on the violence of the Revolutionary War, which was our first civil war, and on the ways that the American founding was shot through with the histories of slavery and dispossession.

But I also mean for students to take up the work of the American Revolution as a fragile and ongoing project for which their generation bears ultimate responsibility. In many ways, it’s that work and the sense that higher ed needs fresh thinking about its responsibilities to primary and secondary ed that brought me to Educating for American Democracy, along with Michelle [Herczog]. As a scholar, I’m interested in what we might call the civic humanities—deeply researched, complex and verifiably true stories told with a lot of why with explicit civic purpose.

We need to acknowledge, as Yoni said, that we hold this discussion at a moment of both peril and possibility. I think the possibility might be harder for us to see, so I want to just highlight that at the outset here. We’ve seen tremendous citizen engagement in the course of the long vicious 2020 election

THE FUTURE OF AMERICAN HISTORY EDUCATION

season. That’s a very good thing. That engagement is not always informed and it too rarely foregrounds the common good or the sense that Americans are one people who can disagree constructively rather than existentially, and those are bad things.

We’ve seen grassroots groups and social media groups—from the New Georgia Project, which seems poised for triumph, to Michelle Obama’s When We All Vote— undertake tremendous civic activation efforts at massive scale. That’s a good thing, but they’re playing catch up educating generations of adults who haven’t effectively learned history and civics in schools and who are too belatedly being given the keys to the country.

So we have work to do in schools from pre–K through grade 20 and beyond. If the Educating for American Democracy approach takes root in primary, secondary and post-secondary ed, I like to think that we could create a virtuous circle, where more students graduate from high school wanting to learn still more about history and government in their post-secondary lives, creating for me more history or government majors, and then where more history and government majors want to be K–12 teachers and see that as the glorious civic work that it is.

From my very fortunate perch at Harvard, I can’t think of anything that I’d like to have my classroom see and do more. APPELBAUM: Ian, Jane has given us a reason for optimism and a reason to think of this moment as one of opportunity. How does that match your mood as you survey the landscape of history education? IAN ROWE: It really does feel like we are living in history. My context is that for the last 10 years, I ran a network of public charter schools in the heart of the South Bronx and lower East Side of Manhattan. Two thousand students, almost all low-income students, black and brown students who were all in search of a better life. Like my own family, who came to this country in the ’60s. My parents certainly understood the country’s history of racial oppression and that their own children might face challenges based on race and other factors. Yet they knew that there was an essence of this country, that there were a set of core values around family, faith, hard work, entrepreneurship, that if embraced, could create a pathway from persecution to prosperity.

I think, with all the flaws that do exist in our country, that’s something that has always struck me as so important, that these principles are worth fighting for. One of the challenges of creating a sense of possibility in young people is to ensure that they actually have a deep and full understanding of the country that they live in, that they come to understand, even after learning all of the flaws, all of the abuses, that we live in a good if not great country, a country that isn’t necessarily hostile to their dreams.

That’s something that we spend a lot of time on, certainly in the schools that I run, ensuring that young people understand the pathways to success that are within their grasp, that have been achieved by millions of Americans by embracing these founding principles. You mentioned The New York Times’ 1619 Project. One of the reasons I think that that created such a stir was that the 1619 Project went at the core of these founding principles—the founding principles were false when they were written, that America has anti-Black racism running in the very DNA of the country.

Imagine if you’re a Black kid in the heart of the South Bronx; you’re nine or 10 years old, or in Buffalo, or Newark, or Chicago, or some of these worst performing school districts in the country, where that curriculum has been embraced, and that’s the message that you’re hearing about the United States. A group of black scholars—we’ve called ourselves the 1776 Unites group, a function of The Woodson Center—came together and said we think that that’s actually a biased and somewhat distorted view of the country, and actually almost a cherry-picked history that paints the country as being permanently in the state of oppressor and oppressed.

We need to ensure all of our kids have a full and complete understanding of everything that has transpired in the United States. We’ve even gone to the level of creating a curriculum, a 1776 Unites curriculum, that seeks to tell, again, a more complete story. For example, the Rosenwald Schools,

—MICHELLE HERCZOG

which many educators aren’t aware of. In the early 1900s, Booker T. Washington and Julius Rosenwald—at the time, the CEO of the Sears company, which was the largest retailer—Booker T. Washington had a vision for exemplary education in a time of segregation. They partnered together to build more than 5,000 schools in the South exclusively for Black students. The demonstrated record of increased literacy [and] community involvement is just extraordinary, one of the most empowering stories about Black self-determination under incredibly adverse conditions, and yet, [there’s] not a single mention of the Rosenwald Schools in the 1619 Project. Our curriculum is seeking to tell all of those stories, so that we understand, warts and all, what America has represented and what should be part of a history curriculum for all students.

Let me just close by saying, in chapter 13 of the Tocqueville’s [Democracy in] America, he said, “The greatness of America lies not in being more enlightened than any other nation, but rather in her ability to repair her faults.” I’ve always found that quote really empowering. because it accepts that America has a flawed history, and yet it has a foundation of principles that allows it to bravely and courageously confront those flaws, and continue to move toward this idea of a more perfect union. APPELBAUM: Michelle, I want to come to you now. We’ve gotten Ian’s view of the landscape from New York. I’m curious—you work with a tremendously diverse student population and the educators who serve them. How do these questions look to you in Los Angeles? MICHELLE HERCZOG: It’s a great question. For me, working with classroom teachers from kindergarten all the way through grade 12, particularly in history and social studies, we’re confronted with a number of issues. I’m particularly interested in, not just what is taught, but even more specifically, how it is taught. How do we entertain these questions and move toward an inquiry-driven approach to teach history in ways that’s going to spark more inquiry among students? We want them to leave with almost more questions than we give them answers to, right? That sort of shifts a whole different pedagogy around teaching.

I started my career actually as an elementary teacher and reading specialist and found that quite fascinating, because we often overlook the capacity of very young children to entertain very complex issues and events and ideals. If you’ve ever been around a 5- or a 6-year-old or a 4-year-old, they know very clearly what’s right and wrong, right? What’s fair and not fair.

I often tease that my daughter’s first two words out of her mouth were “no fair,” because her brother got something she didn’t. They understand that. I think we underestimate bringing some of these complexities to young children, and that’s the key—what my colleagues are alluding to here is digging into the complexities. Traditionally, I think many of us were taught history as just a basic timeline series of events. This happened, then this happened, then this happened, and never really digging into the reasons why, the different responses to the pushback, the support. What we want to do is present opportunities for them to really dig into those issues and complexities.

When I got my history degree at UCLA, it opened my eyes to thinking about history in very different ways than what traditionally I was taught, that it wasn’t just a series of events. There were questions raised, there were stories revealed that were never in the textbooks, that were never in the classroom. That brought a sense of, “Wow, how do I bring that to classrooms?” Now, in my current role in working with teachers of all grade levels K–12, how can I help them surface those different stories, nuances, perspectives, but in ways that are, I wouldn’t say balanced, but that provide a full picture?

We talk about revealing the warts, but how do you teach history in a way that it’s not all warts or no warts? How do you create that sense of, in spite of the difficulties and challenges and missteps and mistakes, that there are glimmers of hope, there were people who worked toward a better society, who worked for a greater cause? And how do you highlight them in a way that doesn’t neglect or overshadow some of the sacrifices very deeply felt by too many groups at too many times? That’s kind of where I work with teachers and try to help them move to thinking about history in those ways and building their sense of understanding, expanding their knowledge base so that they can teach it.

I talk in many states, and when I was president of National Council for the Social Studies, I was able to meet with teachers across the country and found very common issues. The vast not just depth but huge breadth that they are expected to cover. I mean, it’s a race through time. Can you imagine teaching a group of 10-year-olds, fifth graders, everything from the age of exploration all the way through pre-Civil War in one year? To do it well, it’s virtually impossible, especially at a time when social studies is marginalized in the elementary grades.

They’re running a race against time to cover everything, but then helping them to do it well is the big challenge, and giving them the background and confidence to do it with the tools and abilities and background knowledge themselves to feel confident in doing so. It’s a big challenge. APPELBAUM: I want to seize on one of the terrific insights you’ve just given us all. These conversations often revolve around what should be in the curriculum. You’ve just oriented us to think as well about how that should be taught. There was a popular Broadway show a number of years ago, which defined history—and I think I’ll have to clean this up because we’re recording—as “just one damn thing after another,” which is not a bad definition perhaps of what happens in some classrooms.

We’ll come to the question of what we should be teaching in a moment, but I just want to get our panelists to engage with this question of whether there are ways to improve how history is taught, that perhaps we’ll reframe the conversation around what should be taught and allow us to slice through some of the thornier problems there, if history is not simply about conveying a body of facts

—IAN ROWE

and beliefs, but rather about maybe teaching a certain way of thinking or asking questions. KAMENSKY: I’d love to jump in if I could. Michelle, I was flashing during your remarks onto my utter conviction, graduating from high school sometime the end of the last century, of all the things I might do in the world, taking another American history course in my whole life was surely not one of them because of the coverage, the exclusively coverage approach of my textbook, American Pageant, which was the textbook of generations that kids had then. We memorized the height and weight of every president. Taft at 304 pounds, the heaviest. Efforts to reform history and civics ed, I think have often foundered on that.

The death of the national history standards effort in 1992–93 was we couldn’t calibrate the number of George Washingtons per Sojourner Truth that would thread its way across the partisan spectrum. What Educating for American Democracy is trying to do is balance the what, the how, and the why, with an inquiry framework and civic purpose that allows sort of deep core sampling in places that particularly reveal not only the happenings of the past, but the workings of American constitutional democracy.

I guess the other thing, Michelle, that chimed with me from your remarks was your repeated use of the word digging. I think these active gerunds—digging, sifting, evaluating, wrestling, and ultimately coming out with a humbleness before the past, but also a sense, as Ian was saying, of radical hope about what ordinary people can do in the present and future—to me, is the purpose of that kind of active inquiry, which brings what’s done, even in a pre-K classroom, closer to what gets historians like all of us excited in our own work. ROWE: Yeah. I would definitely concur with that, and also just this idea of not looking at historical events solely through a contemporary lens. So often we don’t take into account the actual context. That’s why reading original documents is so important, because you see founders and other people from history and how they were grappling in their context, whatever the factors were, because it’s very easy to say, “Well, I’m looking at that through the lens of now in 2021, I would have never done that.” But challenge kids to say, “Well, here’s what this person was actually facing.”

Imagine 200 years from now, someone looking back might say, “Look at all these people, they had waters on their desks and plastic bottles. Didn’t they realize they were destroying the world? They must have been evil. How could they possibly have made these decisions?” It’s very easy to judge history based on living in a present where all the answers from that point forward are known.

—JANE KAMENSKY

They weren’t known at the time. I think that’s something that’s always really, really important when looking at historical events. APPELBAUM: Let me seize on that and pose a challenging question. If you take this approach to history education, if what you’re doing is presenting students with primary sources, with analytic essays, asking them to dig, asking them to think critically about what they’re encountering, does the curriculum matter? If you’re a high school educator—and I know you’re not particularly a fan of the 1619 Project, Ian—but if you took that as a set of sources and placed it before students and fleshed it out with primary materials, and ask them to engage with it, and to engage with it the way they would engage with any set of historical assets and sources—that is, finding the things in there that resonate being critical of the way sources are presented—would that work as well as any other curriculum?

Does the curriculum matter at all? Or can we simply place our faith in better and more engaged methods of historical inquiry in the classroom? ROWE: Well, the material certainly matters. I don’t know if you’re suggesting it’s completely random. No, you need, in my view, a coherent cumulative curriculum, which does outline what has transpired in terms of American history. The reason I am particularly focused on original documents is that there, you’re seeing the actual history lived out by the people that you’re studying. Too often, there are interpretations such as the 1619 Project that, again, apply currentday ideology to past events, and the two things could be completely disconnected from each other. APPELBAUM: Michelle, let me come to you with a question one of our viewers has posed. They’re in Texas, and they’re wondering that the fights in Texas tend to revolve around curricular standards. They’re wondering whether the focus on the curriculum crowds out the possibility of project-based learning, whether the effort to get everything into a single year in the survey from first encounters all the way through to the Civil War or the present ends up requiring a certain kind of pedagogic approach. Is that something you’ve wrestled with at all? HERCZOG: Oh, absolutely. It’s a great question. A lot of it, unfortunately, is driven by assessments that are required in certain states and schools. If there is an assessment required at the end of the school year that’s going to cover content from this vast breadth, teachers are really challenged to cover all that, because let’s face it, let’s say you’re required to cover 100 years of history during a school year, and it’s on U.S. history in the 1800s, you could spend all year just on the Civil War and still not cover it as adequately as you would like, right?

You can do it and do it really well, but you have neglected covering those other content areas that might be touched on, on the test that students may not be able to perform. So there’s that pressure to just go quickly through that kind of thing. That’s the challenge. Often they’re right, we’ll crowd out project-based learning or inquiry-driven instruction or deep analysis of primary and secondary sources. There is a real tension there. What I have found in some areas is, going back to local control, in some schools and states you’ve got strong leadership at the site or the district level who say, “Hey, we’re not as concerned about the bottom line test result, particularly if it’s a standardized test. We want kids to think, we want them to learn, we want them to take away an understanding of how history was complicated then, and how life is complicated now.”

But that takes some really strong leadership at different levels, and to convince your school community how much does the test matter? Because the reality is it does matter a lot in a lot of areas. So that’s a tough question. In California, they dropped the assessment for social studies. That’s a double-edged sword for us. Because if it isn’t tested, the subject gets marginalized, we get less support, pretty soon it’s less and less taught. Then it’s be careful what you wish for, because if you get a multiple choice test that’s just going to assess factoids and dates, and how much Taft weighed, you’re not going to get to that deep historical thinking that we’re all inspiring teachers and students to come away with. KAMENSKY: The discipline is almost unique at the K–12 level in its allegiance to breadth as the reigning concept. Pressures from both the Left and the Right have perpetuated that sense of what the discipline does. From the Left, a version of inclusiveness that has resulted in creative standards. Add another group whose history has to be mastered without taking anything away, without adding degrees of focus.

I wonder, in the Wikipedia world where anybody can learn quite well-verified content about anything at the click of a button and where our five-year-olds can do it more adeptly than we can, what we might learn from the STEM disciplines, which don’t have this concept of breadth, but have a concept of foundation and activatable knowledge that is experimental and phenomenological at the very earliest stages, but that also has borderline axioms and truths that things don’t fall up.

What we’re trying for in Educating for American Democracy is inquiry-based learning that is not content neutral or content free, but that doesn’t depend on mastering the history of every moment and every group, rather giving the tools that a citizen learner can take into all the other realms of our lives. We’re hoping, especially at the K–5 grade level, for real partnership from English, language arts and STEM teaching, because maybe that’s the age where the disciplines are less set in their ways. APPELBAUM: But how far can you push that? Could you do a history education which is solely based in America in the 20th century and rely on students to go on Wikipedia to find out that there was a revolution? Are there limits to that kind of pedagogic approach? ROWE: Well, you can have culminating projects that require that kind of interdisciplinary analysis. Yeah, I think you can. As Michelle said, a lot of this has to be coordinated, similar to what it sounds like you experienced in California. In New York in 2010, the state and the regions decided to eliminate the social studies exam. Literally, you can see, over the last 10 years, the amount of time in the average school day, where a kid

was getting five days of social studies and history, great substantive content, now on average is only between one to two days; that other time has been replaced by content-free material, which is all about finding the main idea without actually adding substantively the body of knowledge that kids need to function in our society. I do think there’s a way to get there. There has to be coordinated agreement, though, that assessments in addition to curriculum and standards are all working in line with each other, as opposed to actually working in opposition, because that’s what we’ve been getting through these assessments. APPELBAUM: This is not a simple needle to thread, right? On the one hand, if you’ve got the tests, you risk the forced march through the content, and if you chuck the tests— ROWE: But that’s test design. HERCZOG: We’ve advocated a lot for performance-based assessments in history that can really measure some of the deep critical thinking we want to see.

I don’t mean to paint such a grim picture, but if you look outside of history instruction, the way STEM is taught, the way math is taught now, even English, especially if you’re a state that’s adopted the Common Core approach, it’s about problem solving, critical thinking, going beyond the Wikipedia approach to teaching. If the other disciplines are moving in that direction, why not history?

That’s our rationale. Think about it. Your students are not in their third-period history class all day long. From you, they go to math, they go to English, they go to these other subjects that are taught through an inquirydriven approach. Why aren’t we being consistent in approaching history education that same way? This is sort of the marketing technique we’re trying to use to help teachers move in this direction. That it’s not just the march through time; that we want kids to use that same pedagogical approach when teaching history and social studies. KAMENSKY: I want to stand up for the olden days though, for a minute. Yoni gave us the provocation: Could we imagine only staying in the 20th century? I’ll plant two flags. First, teaching American history to the students of America in the United States. It’s crucial that they know something about the founding history and principles of the country, and it’s crucial too, I think, sort of humanistically and philosophically, as kids orient themselves in the world, that they learn something about deep time and moments when people live. As Ian was saying before, people lived our past facing forward to their future.

Today

is a good day to join, renew or give a gift membership

You already know that pictures of cute animals catch people’s attention. But did you know that joining The Commonwealth Club of California opens up a whole new world of learning opportunities and the chance to interact live with not only headline makers, but also fellow highly informed and involved citizens? Now more than ever, the Club plays an important role in informing people and connecting them.

The Commonwealth Club of California is a nonprofit, member-supported public affairs forum. Your tax-deductible membership gives you up-close and personal access to the thought leaders of our day and opens the door to nearly 500 events we present every year.

commonwealthclub.org/membership

—IAN ROWE

That’s a really important takeaway from history that I still am teaching to graduate students. It’s not easy. I think [being able to understand] the different complexities and contexts of our past as a people is vital. Whether we could cover the past by doing something that’s much closer in approach and in content to a case study method than I would say the “olden days” are important, but the revolution is more important than the War of 1812. The Industrial Revolution is maybe as important as the Mexican War though, the Mexican War may be more important to students in California and Texas than it is to students in New England and the upper Midwest. So maybe post holes rather than the sort of whole-cloth method could serve us. ROWE: To Jane’s point, I think the act of prioritizing what is most important is something that we have to do. What’s happened now in sort of a politically divided culture is that there are lots of people competing to say what is the most important element of American history. That divisiveness, in my view, is actually leading to people saying they just don’t want to engage so let’s not even teach this stuff in the first place. The only people who suffer in that approach are our kids. We’re not getting a sense of our country. HERCZOG: We talk a lot about, Do you want to teach well—and slow down and teach well—or do you want to teach fast? These are the conundrums that teachers are faced with all the time. Where can I slow down and go deep, dig into a topic that we feel is most important, like the ones you were alluding to? But there’s a cost of going fast in other areas too, if there’s some local interest in those areas. The big question for us, and if you have children of your own around the dinner table, it’s, Why do I have to know this stuff? Why is this important? It’s a bunch of stuff that happened a long time ago.

But what I love to see most is when teachers connect that past to what’s happening today. The lessons of the past will remain in the past if we don’t connect the dots to events and people and things that are happening in today’s world, if we’re not learning from it and moving forward. You talk about [how] the revolution today needs to continue. Yes, we’re standing on the shoulders of all of the past events and people of our American past. How do we build on that? How do we learn from that? I think that’s a piece that’s been largely missing. When we talk about civic learning, that’s where it leads, right to civics.

How do we engage and make history today by learning about what works, what doesn’t work, and building on our own knowledge to create a better society for all? APPELBAUM: The question I want to pose, Jane, [is] there is a certain tension that I’m hearing, where on the one hand, Ian tells us that the danger of many contemporary history curricula is that they see the past through the lens of the present. Michelle reminds us that students need to understand that these are foundational pieces of knowledge that they’re going to require in order to interpret the present, and if they’re not making those connections, they won’t be engaged. Is that not a false tension? Is there a way to thread that? KAMENSKY: No, I think part of our sense of that tension comes from the fact that first higher ed, and then PTA’s, and K–12 evacuated these spaces in the last moment of partisan collapse in the late 1960s. We waded out of this territory because it seemed too fraught with tension between the immediate relevance of the present and the sort of stable content of the past. I’m interested in how we can be true to the past and teach the ability to evaluate closer to objective truth and farther from objective truth—that’s clearly needed in our society—but also empower teachers and their parents’ communities to be courageous about wading into subjects about which there is disagreement in order to teach those evidence-sifting skills that will allow us to disagree better, more civically, and more productively.

Ian and Michelle, with their K–12 experience in different ways, have a much better sense than I do about how to empower not just the great teacher but the average teacher to be skillful and fearless. So not just good rather than fast, but also courageous, and yet supportive. How do you do that? APPELBAUM: Ian, we’ve got a high school teacher in our comments who says that they increasingly feel like they are walking on eggshells in the classroom. What would you say to that teacher? ROWE: Thank you for doing your job on a day-to-day basis. I empathize with that. One thing I’ll say, in defense of the 1619 Project, is that they clearly have unearthed a desire for teachers like your questioner to grapple with these questions with their kids. America has a very complicated history, and so teachers are yearning for materials to tell that story. With the group that we launched, 1776 Unites, we created this curriculum because we thought that the 1619 Project is so cherry-picked to fill in this narrative of an irredeemably racist country.

We said, You know what? Let’s use a strategy of storytelling. Let’s create great materials that teachers that are interested in teaching this can feel more confident that they can have these discussions. For example, Biddy Mason, who was a woman born a slave and ultimately died a millionaire and a philanthropist, an incredible story; we now have a whole curriculum unit on Biddy Mason that goes through the life that she led, the struggles that she had to overcome, all of the abuses, and yet, she was able to embrace these principles around faith, family. She was a great entrepreneur.

Those are the ways in which we’re trying to connect the past to the present, because at the end of each unit, we want to ask the kids, What did you see in Biddy Mason’s story that you think can resonate with your own? And how do you think you can now apply this in your own contemporary life? We think helping teachers by providing these kinds of materials that we think tell a more complete story, that’s not running away from the negative aspects of our country, but also highlighting those stories about average individuals who were able to overcome by embracing principles that are as available to you today as they were 200 years ago.

Thank you to that teacher. Take a look

at our 1776unites.com website. There’s a curriculum there that hopefully can help you have those kinds of conversations without walking on eggshells. HERCZOG: Yeah, I think that’s a great example, because of stories like that are empowering to young people today, but you have to do it with wide-eyed empowerment. Understanding that wasn’t so easy for Biddy Mason. She faced a lot of threats and discrimination, and so where do you draw the line? But I’m really glad the teacher raised that issue, because that’s something we need to focus on. Kids are watching the news today, just like we are. Unfortunately, most of them are watching it through social media so they’re getting all kinds of different points of view of that. But they’re concerned, they’re hearing, they’re watching, they’re very attuned.

They want to come to school and talk about these issues, but we’re finding more and more this issue of fear in the classroom, because these things have become so politically motivated, so politicized that teachers are very nervous and rightfully so to bring up some of these topics in the classroom, because kids are coming with those political ideologies as well. They’re bringing them from home. We’re finding, unfortunately, even though this is a prime time to have discussions in classrooms about these controversial issues, unfortunately, we’re finding more teachers fearful of doing so because things are so politicized now. But it’s more important than ever.

This is where civics plays a very, very important role. There are approaches and strategies that teachers can find on how to facilitate these conversations about controversial issues. Dr. Diana Hess at University of Wisconsin–Madison is our primary go-to. She’s a leader in this on the national front. Structured Academic Controversy, Socratic seminars, Philosophical Chairs, Constitutional Rights Foundation—a lot of these civic ed organizations have great materials to help facilitate those conversations. They need to occur in classrooms, because that’s how we’re going to prepare young people to address and discuss issues in ways that are respectful, that are civil.

Unfortunately, [it’s] not being modeled so much in our political landscape today, but if we can teach young people today how to discuss something that is controversial with people with different views, in ways that are respectful and civil, that’s how we strengthen our democracy. There are many who feel that the lack of civic learning in several years past—we talk about the marginalization of history, but marginalization of civics has even been worse. When we don’t provide those opportunities, many feel that a lack of that over the last years has led to where we are today. KAMENSKY: When I hear the walking on eggshells question, I’m aware that it means different things to the Left and to the Right. But I think across the political spectrum it does testify correctly to a brittleness in our current civic culture and to the extent to which we see competing absolutisms, and a sense of, in some young people, including my two young Robespierre sons who are home from college downstairs, a sense that they’re not groping toward a more perfect union— they have the perfect answer, right? You bring competing absolutisms to a conversation in a classroom over a difficult issue, and you have a disaster.

I share Michelle’s sense that more nuanced historical and civic education braided together will equip young people to do better, to bring a less brittle texture to our political culture in the future. I will confess that I share that sense of walking on eggshells when I come to my own incredibly privileged classroom and teach issues around race, gender, sexuality. Part of the empathy and humility that our core historical skills can help students to do better to be more—not prissy civil with each other, not sort of fakey-fakey clutch-my-pearls or don’t-clutchmy-pearls civility, but a kind of generosity and willingness to build coalition and to think about where compromise can be constructive.