32 minute read

Michael J. Fox The actor, author and ac tivist on his life since he was diagnosed at a young age with Parkinson’s, and

MICHAEL J. FOX

No Time Like the Future

ELIZABETH CARNEY: Michael, we’re delighted to have you here. Thanks for coming to The Commonwealth Club Business and Leadership Forum.

I want to introduce Michael J. Fox a little bit. He’s written a new memoir about his recent life after he was diagnosed with early onset Parkinson’s disease back in 1991, when he was 29. If you don’t know, Parkinson’s is a progressive neurological disorder, which results in tremors, muscle spasms, balance coordination problems, diminishment of movement and can also affect speech, mood, sleep, and lead to fatigue. Over 5 million people have Parkinson’s.

Michael J. Fox became famous in his 20s before Parkinson’s for his role on the hit sitcom “Family Ties.” In the middle of its run in 1985, Michael starred in the international hit Back to the Future. He’s also founded the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research, which has raised over $1 billion—that’s with a B—for research and is celebrating its 20th year. His memoir is called No Time Like the Future: An Optimist Considers Mortality.

Welcome, Michael J. Fox. I’m curious, you write a new book, and just when it is finished, COVID comes. You went back to writing an epilogue. In light of this pause, how did you respond? MICHAEL J. FOX: Well, it was really interesting to be in something so navel-gazing.

disease changed the life of Michael J. Fox and his family. He joins us to explain how he met the challenge and how he continues to deal with it. From the March 2, 2021, Business & Leadership MLF online program “Michael J. Fox: An Optimist Considers Mortality.” Produced in association with the Michael J. Fox Foundation; part of our Good Lit series, underwritten by the Bernard Osher Foundation. MICHAEL J. FOX, Actor; Advocate; Author, No Time Like the Future: An Optimist Considers Mortality ELIZABETH CARNEY, Entrepreneur and Business Leader; Chair, Business and Leadership Forum, The Commonwealth Club—Moderator

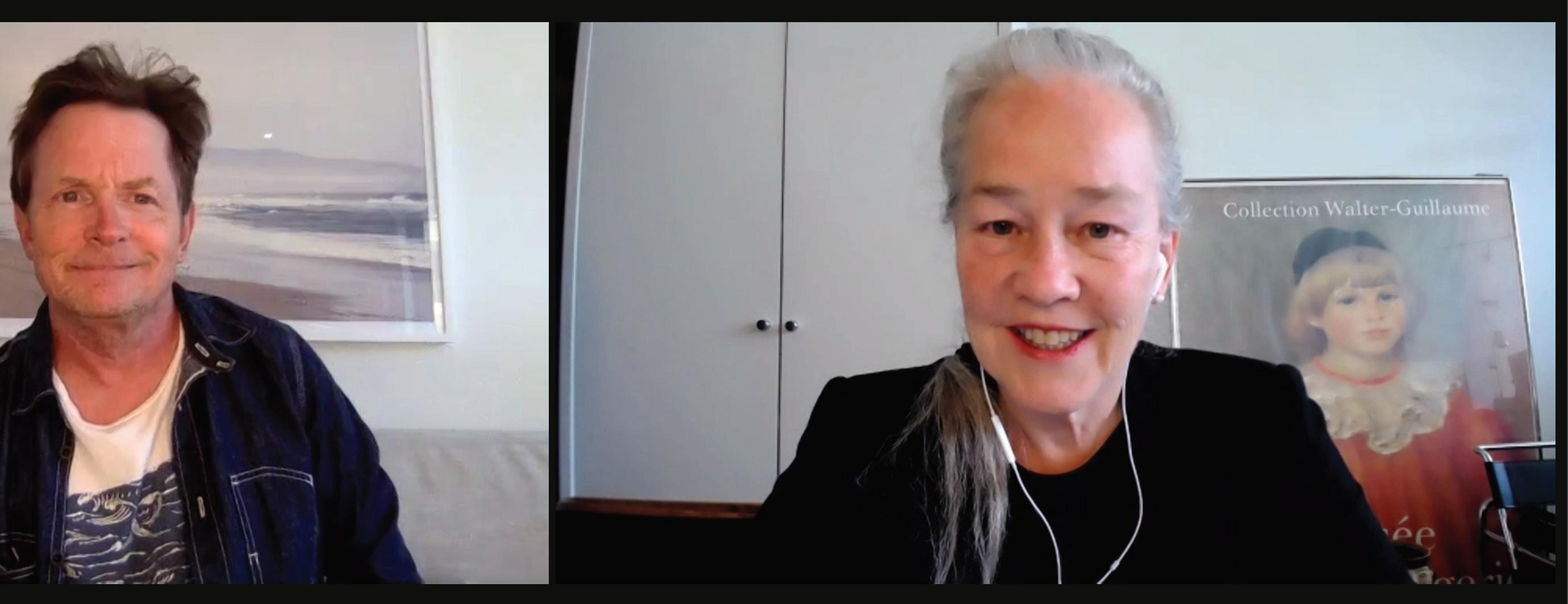

Left: Actor, author, activist Michael J. Fox. (Photo by Mark Seliger.)

It’s a very personal, very tight little memoir of a period of time in my life when I had some challenges. Meanwhile, the whole world is challenged by this virus. I don’t type, because my hands don’t work well, and I don’t write because it’s illegible, although I can read my notes. So I have a partner, Nelle Fortenberry, who has been my producing partner for years on television, and she patiently sits and I dictate to her, and she types it out. What was challenging about being in quarantine was I was in quarantine in Quogue, Long Island, with my family, and she was in Sag Harbor, Long Island, just a little ways away—but she couldn’t get out and come to me. So we did it via FaceTime. It was really interesting, because we were so tight, and we’re set on dictating stuff and getting my story out and she’s getting it down. Then I excused myself to leave the room for a second and get a glass of water, and I bring two back because it just felt like she was there. It was so personal and the dynamic between us was so tight.

Then in the rest of my life I was quarantining every day. My whole family was there except my son, who’s in LA. But my daughters, and Tracy, and a friend of ours was there, and we were quarantined in the house and it was lovely. We did jigsaw puzzles, and Tracy made great meals, and we had great conversations. I was so impressed with these young people talking about social justice and the ramifications of the virus. Yet at the same

time we were aware of the utter agony that was going on in the rest of the world and the pain that people were going through, people dying in corridors in want of a ventilator. It’s just all this awful stuff.

But that was that flavor that I was writing. I felt compelled to write that epilogue to just kind of put it in perspective, to say that as I wrote this personal story, I was aware of the greater drama going on. CARNEY: That’s a lovely silver lining for your own personal experience of COVID. How about in the book tour? How has it been being virtual? FOX: It’s really amazing. I don’t think I’ve

worn a pair of anything but sweatpants in years, it feels like. But it was a great experience. Certainly I like being spared the travel. It was nice not to have to go to Oxnard, someplace way off the map. And to just be immediate and to go some days one conversation to another conversation, and about the same thing, coming at it from different angles. I was talking to Jimmy Fallon and Marc Maron on the same day, and you get a different spin on it, and it was a really good experience. People, fortunately, really like the book, and so they asked interesting questions that made me think about it. They found the material compelling, so the conversation was compelling to me. CARNEY: And always fresh. Tell us a story about the book. There’s a significant story that you recount about your own brokenness, and your challenge to optimism that you’ve always recognized in yourself. Maybe you could share that with some of the audience that hasn’t read it yet. FOX: The book takes a lot of detours and goes to a lot of different places; it’s more about mood or tone. It’s not linear. So the story of the book is I’ve had Parkinson’s for 30 years, so I have established kind of détente with it; I have an understanding with it. It takes up its space, and I take up my space, and it’s always infringing, and always moving in. But I’m aware of it, I can hand-check it, and I can keep it at bay. But then I got this thing, this spinal tumor, a benign tumor on my spine, and it was threatening me. I already had gait

and walking difficulties from Parkinson’s, but it was making my legs weak, and it paralyzed me in short order.

So I went to a series of doctors to see what they could do about it, and most wanted nothing to do with it. Then I found this doctor at Johns Hopkins, Nick Theodore, who was fantastic. Brilliant surgeon. I said, “What about all these doctors that won’t touch it?” And he said, “Well, it’s a horrible tumor, and it really is infringing on the spinal cord, so it’s very dangerous. So who wants to be the doctor who paralyzes Michael J. Fox?” That was the funniest thing I ever heard. And I thought if he has the guts to say that to me, he’s got guts. So we had him do the surgery, and he did a wonderful job. He arrested the gradually worsening symptoms, which was what his hope was—to arrest the progress of those. He couldn’t do anything to reverse the damage that had already been done. But he could stop it in its tracks, which he did, and subsequent MRIs proved that out.

It was an intense experience, and I couldn’t walk afterwards. He assured me that it was temporary, and I had to do all these walking exercises; I had to literally learn to walk again. You hear people say that; it always sounds hyperbolic and self-dramatic, but it’s true. You have to learn to walk again, you have to learn to transfer weight and to recognize when the pressure’s going off your heel to the middle of your foot to your toes. My tendency is to want to get on my toes, and I fall forward. And it takes all I can [do] to live in my butt

and my heels.

So there was all that stuff going on, and I had 10 days of intensive rehab in Baltimore, and then I had another couple months of intensive rehab in New York, at Mount Sinai. Finally, I was in this place and I had all these wonderful trainers and medical daycare caregivers and doctors, and my family was so supportive and so great. I just didn’t want to do anything to let them down. I loved that they were proud of my progress, and my son would show up at rehab and cheer me on, and Tracy was fantastic.

And then I got cocky, and I thought I was doing better than I was doing. I was going to New York; I was in Martha’s Vineyard on vacation with my family that summer. August 12, I left the Vineyard to go back to the city to do a cameo in a Spike Lee movie, and I was all excited about it. My daughter came back

with me from the Vineyard, but I wouldn’t let her stay at the apartment. I had to get up the next morning and go to work; she said, “Let me stay and get you ready, and get you out the door.” And I said, “No, I don’t need any help. I’m all right.” So I sent her home.

I woke up the next morning and started to make my way to the kitchen to have some breakfast, and as soon as I got in the kitchen I took a turn and slipped on the tile floor, and shattered my left arm. I broke my humerus all the way down; it was twisted, messed up.

I didn’t know the extent of it yet, but I knew it was bad, and I knew there was no one there. I crawled over to the wall, and got my

cell phone, and called my assistant. I couldn’t call Tracy, because she was on the Vineyard, and that would just freak her out. I couldn’t call my daughter, because it would be cruel to her to call her up and say that I had hurt myself, because she had wanted to be with me. So I call my assistant, and she called the ambulance.

As I sat there on the tile floor, leaning against the wall with my arm out of commission, I just thought about what a bad guy I’d been. I had taken all these peoples’ love and support for granted, and just disrespected it. I felt I’d let down all these people, and I thought, How do I put a happy face on this? How do I translate this into Michael Fox positivity? There’s none of that, this is garbage. This is nothing but pain and regret. This is not good; I mean, how can I be optimistic about this?

Then I started thinking, Is my optimism finite? Has it reached the end? Is this the end of my ability to accept? It’s all gone. I lived on that. I lived on my acceptance, and on my optimism, and my ability to see past the current situation. I thought, Had I let down the Parkinson’s community? Had I let down all the people [to whom] I said, “Go ahead, chin up, be positive. Good things will happen”? Had I been lying to them? Had I been deceiving them? Had I been putting up optimism as a panacea, commodified hope? I just had all these questions, and it became an intense time for me. And it was funny, because Parkinson’s is obviously a very serious

situation, and life altering, but it snuck up on me. It was unbidden. I didn’t do anything to have it happen; nothing. And the tumor, same thing. It just kind of snuck up on me. It was there, and had to be dealt with.

It took time. All this stuff happened over time. The broken arm was like that; it just entered my life, and I had to go back to rehab, and I knew what it meant. It meant a lot of pain. It’s one thing to have a shattered arm, and have difficulty walking because of a tumor on your spine, and have Parkinson’s. It just was—I didn’t know how to sell that. I was out of happy-face stickers to put on it. I said to myself, Making lemons . . . I’m out of the lemonade business. Can’t do it anymore.

So it was a difficult time, but what it forced me to do was to reinvestigate all those places in me that used to manufacture optimism and find out what was missing, why I could no longer find a silver lining in this. It was a great journey, and I reflected on travels I made in my life, and how they informed my point of view, and relationships, and television, and all kinds of stuff. CARNEY: The thing that stands out for me is that somehow in the writing of that book, you transcend your former self, and you bring a level of authenticity, a deeper sense of trust for all of us that there’s a way that you hold hardship and loss in a way that is also possible at the same time. It makes me think maybe vulnerability is the new superpower. FOX: Honesty certainly is the superpower. [Author and UC Berkeley journalism

professor] Michael Pollan, who we both know, is my brother-in-law and is a great support and a great resource when I’m writing. After the fact, it was very positive. He loved this book and was very supportive of it. He said it was very concise. It’s concision was the strength. He always says to me, “velocity and truth,” and it had velocity, and it had truth.

So it was a really interesting book to write, because I remember being really specific when I was writing, and as I said, my process is dictation. I would hear the words that I [spoke], and it’s funny, because if you’re timing a joke, for example, it’s really different to do it on the page than it is to do it in person. I can create the timing spaces, but if it’s written, you’re creating the timing spaces when you read it. My challenge then becomes, How do I write it so that you’ll read it the way I want you to hear it?

What happened was when I was writing, that just happened. It’s a spoken book. It isn’t a lot of “and the curtain rippled in the wind, and it was colored by the translucent pool of light.” You’re just like, “There was a window. There was a window and I went through it.” Just the facts. CARNEY: You wrote in your book about your father-in-law, and how you used to talk to him about different challenges that you had. It made me wonder if sometimes his spoken word also came through in your writing. He had some good advice for you, I recall. FOX: Yeah, he was terrific. He was such a nice man, such a good man, a wise man. I wrote about a couple of encounters we had. We had kind of a tragic-comedy one toward the end of his life. But at one point, he would sit at the table in Connecticut, the country house, and he had a sweater on, a button-up shirt, a hat, and a few days of grizzle. And he’d be reading the Times, so that was always the time office hours were open, you could go and visit him. So I sat down in front of him. At the time I was thinking about the wedding vows, and Tracy having agreed to “in sickness and in health.” I didn’t know I’d have to cash that check. I didn’t know I’d have to ask her to redeem that.

So I said to Steve, “I don’t know if she signed up for this. In sickness and in health, and she has to deal with my sickness.” He said, “Well, you did okay on the ‘for richer, for poorer part.’” He went on to say, “That’s not about money.” That’s when he made the jump. He said, “That’s not about money. That’s about: it is a rich life. You have a rich life, and you have to recognize that, and accept the other stuff. Accept it, understand it, process it, but move on from it, and live your life.” He was all about acceptance, and he was all about gratitude.

And that gratitude, as I wind my way through this journey, was the ultimate redemption. It’s in gratitude that, whatever you go through, whatever you experience, whether it’s a pandemic or a flat tire, there’s something to be grateful for. There’s something in there to be grateful for. That flat tire may have saved you from an accident. The pandemic may force you inside with your family, and you form bonds with them that you didn’t have. Always something.

What I puzzled that out to mean was, if you can find that gratitude, then optimism is sustainable. CARNEY: Optimism is sustainable. FOX: With gratitude, optimism is sustainable. CARNEY: Beautiful. Yeah, when COVID started for me, I was on my exercise bike, and I dislocated me knee, and somehow it felt like I had a turtle sitting on my knee sending me a message, and that message was “Slow down and listen.” So that’s my little silver lining for COVID. But I think that there might have been a turtle that has been a thread through your life, and I was hoping maybe you’d share that a little bit. FOX: In the late ’90s—in fact, New Year’s Eve going into the year 2000—we were down in the Caribbean with the family, and having vacation. I was in the middle of the dilemma. I was trying to figure out whether to stay with the show, with “Spin City.” The show was doing really well, and it was a success, and I loved doing it. But my symptoms were becoming too great. I had already gone public with it, and people knew I had Parkinson’s, but it was becoming a strain. And I wanted to get going on this foundation. I wanted to create a foundation that would realize the promise of the science, that it was really looking good. I kept hearing this idea that the science was ahead of the money, and if we get that money to catch up with the science, we’d get stuff done.

So I was thinking like that, and I was thinking, Am I better having the show and having a high-profile platform? Or should I just start the foundation? So with this in mind, I went for a swim, my last swim of the year in this little bay. I came upon a turtle very shortly into my swim. He was a really rough-looking character; he had a bite taken out of his fin, he had a scar on his beak. And he kind of tolerated me; he just kind of looked at me, took me in, and kept going slowly on his way through the weeds at the edge of the reef. I followed him for about 20 minutes to a half an hour. Then I got out, and I walked up on the beach, and I went toward where Tracy was sitting. I picked up a towel and I started toweling myself off. And I said, “I’m leaving the show. I’m going to start the foundation.”

Then when I was going through all this stuff this past couple years, I just kept thinking about that turtle, and I kept

Michael J. Fox was interviewed by Elizabeth Carney, chair of The Commonwealth Club’s Business & Leadership Member-Led Forum.

thinking, “That turtle’s going to get me through this like he got me through the other thing.” So as a reminder of it, much to my wife’s chagrin, I documented it on my arm. [Displays his turtle tattoo.] CARNEY: Oh, look, there he is. FOX: The artist put the five rings to signify the five decades of my life; I’m now on the eve of 60. It was nice. And every time I see it, it makes me think. CARNEY: And you have the right to go where you want. FOX: Yeah. And wherever it takes me. Not even as much where I want. Where I want is not always good. Where life takes me always presents me with an opportunity for gratitude. Whatever [happens], I can’t control it. I can’t undo it. But I can meet it, and accept it in order to understand it, and go in another direction.

I didn’t put this in the book, but it was a driving-force idea behind the book when I started it, but I view life as a series of choices and circumstances. You had a circumstance, you made a choice, moves you to another circumstance, you make a choice, moves [you to another circumstance again]. And you stake and ladder your way up to whatever your destiny is. But each one of those choices you made, and each of those consequences of those choices formed who you are, or formed who I am, formed all of us. Being too rigid, if we really overthink our choices, we get compromised circumstances. CARNEY: Right. And that turtle with his raggedy self helped to lead you in that particular direction. FOX: Turtle’s just a turtle. Turtle is a turtle is a turtle is a turtle; but he goes places, and he gets in currents. A couple years ago, just before the virus, we got back from Vietnam and Cambodia on this family trip—we go with a couple other families; we went to Africa one year. We were on this island down in the south of Vietnam, and they were releasing turtles. It was New Year’s Day, and they were releasing baby turtles. I kept thinking, I realized there’s birds and other predators. It’s a very serious trip from where the nests are to getting to the water, and the odds against them making it are huge. So the odds of him getting to a place where he’s swimming in the reef, and he’s all chewed up, but he’s there, he’s doing it—that guy’s been through some stuff.

It made me think of something Chris Carter, the football player, said. He was talking about his drug issues when he was a younger man, and he said, “I don’t know a good man who hasn’t been through something.” And it’s true. We’ve all been through something. CARNEY: Yeah, and it helps us to earn the choice to go in a certain new direction. Maybe for a moment we ought to also acknowledge Gus, who is your dog and probably helps you go in certain directions all the time. FOX: He’s ailing right now. He’s older. I talked about it a little bit at the end of the book, the unfairness of a dog’s short life. And he’s struggling. He had a bunch of issues this summer. He had a splenectomy, because he had a thing in his spleen. His stomach flipped over because he’s a big dog, he’s part Great Dane, and he’s older. But he’s so sanguine. He’s so chill, which is great. He’s always been a great dog. He’s huge, but he’s always been sweet, and gentle, and approachable. Loves kids, loves little dogs. My son had gone to college, and I had my three daughters and my wife in the house with me. And we had a small dog name Daisy, female dog. I was drowning in a sea of estrogen, it was just too much, and I missed my son, and I missed that male presence, and that buddy.

We went to Martha’s Vineyard and we saw a thing on a bulletin board outside the Chilmark [General] Store—you get piano lessons and gardeners and babysitters and fishing guides. And then they had a thing about this dog, Astro; they called him at that time, soon to be Gus. They described him as being a big, Great Dane/Lab mix. It turned out he had no Lab in him. But I was really interested in the dog. I got home, and Tracy said, “I saw this thing at Chilmark Store on my bike trip today.” I said, “Was it about Astro?” She said, “Yeah.” And I said, “We got to go see this dog.”

So, we met him. That was at a stage of my Parkinson’s when the foundation was going well, and everything was going good in my life, except this absence of my son. I needed somebody to spur me on to walk and to exercise and to get out. Taking this big dog, who people would see us and say, “Why don’t you get a saddle for that?” But we would just go around the neighborhood, and we’d walk three, four miles every day. He got me to do that. He got me to interact with people, because he was a magnet for people, and people would come up and talk to him, and

to me. Tracey would say, “They just want to talk to you.” I said, “No, I’m invisible next to this dog.” CARNEY: It’s the dog. FOX: But yeah, it was a great bonus in my life to have Gus. CARNEY: Well, it’s been a really amazing thing that you’ve created, what you’ve done on the foundation side, too. I don’t want to let this opportunity to go by to talk about the foundation, because the way that it might’ve been envisioned when you first started and the richness of all that you’ve done to innovate since then has been pretty big—wow. I mean,

I have so many different questions that are from my own life. My mom was diagnosed with Parkinson’s when she was 60, and she lived 20-some more years. But it was before you started the foundation, and we could see how much it was needed when you did start it.

First was founding it so you could have some research that would support your process, and that makes me ask about the growth of the whole thing. So maybe you could talk to us about some of what you discovered, because it was at the beginning of the internet. You had to discover that you could actually find other patients like you on the internet. Tell us a little bit about that journey. FOX: When I decided to go public and let people know I had Parkinson’s, I had had it for seven years before I decided to tell people about it other than my family and close friends. As you say, [it was] before the internet, the easiest way to get something out before the internet, you tell Barbara Walters or People magazine. So I told Barbara Walters, and everybody knew. But there was a little bit of internet actually, it was AOL. And when I first disclosed it, a lot of the tabloids went crazy with it, and they made it this pitiful, sorrowful thing, and I really rejected that. I thought maybe I’d made a mistake in going public, because I was getting this reaction.

But people in the Parkinson’s community had a completely different reaction. People in general were eager to get the information and were curious in a good way about what my situation was, and what it meant, and what the disease was. They always thought it was an old person’s disease, and the fact that someone 29 years old was diagnosed with it was really new to them. Then I got on the internet, and I started hearing the patient community. I said, “Wow, this is a thing. I’m being presented an opportunity here to do something.” This was my negotiations with myself that led to the turtle. But I thought, “This is a real opportunity, and you don’t get these often.” In life, you have to recognize when they come.

So I started the foundation, and Nelle Fortenberry, the same person that I dictate to and my producing partner for years, she was in on the ground floor. She was our first board member, and she helped me find Debbie Brooks, who is our co-founder and just an amazing person. Debbie Brooks is just a force of nature. She was a young person who had great success on Wall Street with the world’s biggest bank. So she came on board and very quickly got our execs lined up. Early on we got a grant out to a couple of researchers, small grants, $300,000, $400,000 from initial donations that we had, and I’d done my first book and that went to the foundation. So we put together enough money to get a small grant program together, and then it just grew very quickly. Our motto was that the science is ahead of the money, so we wanted to catch up with that, and we started seeing what the challenge was. We thought we’d go for low-hanging fruit; we didn’t realize that low-hanging fruit was planted in the middle of a moat that you had to climb down to climb out of, to get to that low-hanging fruit.

We realized we got into a broken system that wasn’t designed for success, so we had to remodel that, remake it, and create it for ourselves, a vacuum tube to get the money to where it needed to go. I also very early on nixed the idea of having an endowment. I didn’t want to have an endowment, I didn’t want to have money sitting around, I didn’t want to invest money. I wanted to invest money in research, and we started doing innovative things like pay gigantic, multibillion-dollar pharma companies to target our compounds, and say, “We’ll pay for the initial research. We’ll cover that, and if it hits, just promise to carry it on.” We have several relationships like that that paid off; they did exactly that. And we got a few drugs through to the FDA, and it’s been a success on that level.

We have programs like a big biomarker initiative that is about finding common biomarkers in people with Parkinson’s so that we can actually recognize that biomarker before symptoms are evident and treat it prophylactically. CARNEY: There’s a few different kinds of Parkinson’s, so that must already be pretty interesting. You’ve got a cluster, and look at patterns. FOX: Everybody’s got their own version. We’re trying to find the genetic links, and what proteins do, like alpha synuclein, and how it folds the cells in the brain, and it’s all that stuff. I’m not a scientist, but I’m amazed by that. But the cool thing that happens with the foundation, separate apart from its scientific mission, was it became a magnet for people with Parkinson’s and their families. We were able to create programs. We’ve created, on the fundraising side of things, Team Fox, where people run marathons and climb mountains and have bike races, and sold lemonade and did whatever they did and raised money. And then we have, more important probably, got the patient involved on a research level. We created Fox Insight, a place where patients could share their anecdotal experience and create a living journal of what they go through, what their needs are, and their state of mind. We get patient councils. It just became this great thing where it was much bigger than me swimming with the turtle; it was a big convening of people with concerns. CARNEY: The thing that shows up in all of these different pieces that you’ve done is that the unintended consequence maybe has been creating community, and finding each other, and knowing that you’re not the only one out there; there’s all these other people that are bringing their courage to this. FOX: Creating community, I think, is recognized with treatment, and allowing space for that community to feel in their own space, to claim their space. CARNEY: We know you’re a guy who takes risks, that’s been true ever since you held onto the back of the car and skateboarded or whatever it was [in Back to the Future]. But I remember in the early days of the research foundation that you’d go fund a small study in China on green tea, and you’d do things that were really out of the box. FOX: You have to include that in the mix. You have to include opportunities for surprises, and things that you don’t expect, because we don’t have a cure yet.

We put $1 billion into it, but we don’t have a cure yet. It’s elusive, and it’s not going to be right there where we expect to find it. So we do the traditional research, but we allow for studies on green tea, studies on— CARNEY: Microbiome, and— FOX: Everything. Nothing is shut down. CARNEY: The environmental and toxicity issues, have you also looked at that as veterans have been especially impacted by Parkinson’s? FOX: One of the things we discovered early on was that we all agree that the genetics loaded the gun, but environment pulled the trigger.

So you can have predisposition to Parkinson’s but never find that triggering agent that sets it off. But what was that triggering agent? It could be anything. It could be pesticides, it could be metal exposure, it could be head injury. Those things are all still open questions. It could be all of those things, and therefore the differences that you’ve alluded to in peoples’ Parkinsonian profile, there’s so many things that it could be. Usually, if you can find cause, you can find a cure. But we think we can find a cure before we can find a cause, and backstep it and find the cause and eliminate it. CARNEY: Are there root causes that you think are particularly likely to be the bad actors? FOX: Definitely pesticides and pollutions and man-made contaminants. And naturally existing contaminants in some cases, perhaps. CARNEY: So part of it is we’re poisoning ourselves. FOX: Well, we could be. We don’t know. You have to pick which ones you put the big thrust behind. What we’re trying to find is this commonality of symptoms, and you alluded to it before, whether it’s constipation, lack of sleep, lack of taste, inability to smell, to gait and muscle reactions. And everybody gets a sampling of it, but if we can boil it down to the genetic makeup of the people who have all these symptoms, and take this cohort of 100,000 people, let’s say, then we whittle them down to 15, to 10, to 5, and there’s our answer. Whatever they have going on. And then we’re doing other stuff like supporting the creation of ability to image the inside of the brain, and see exactly what’s going on.

So there’s no one path. I can’t say, “This is our goal, and this is the path we’re going.” It seems kind of scattershot, it seems like throwing spaghetti against the wall, but it’s not. There’s a method behind it, which Debbie and Todd Sherer, our CEO, are investigating every day. CARNEY: You have surrounded yourself in working relationships with strong women. It’s so great to see that as a pattern and cluster in your life. I mean, Tracy, she’s amazing, but also your partner at the foundation, Debbie Brooks, and your producing partner, Nelle [Fortenberry], and your three daughters, and your assistant, and Nancy— FOX: And a mother and a grandmother who convinced everybody that I was for real. All the adults in my world when I was little thought I was a flaky kid who was too little and too crazy to amount to anything, and she would say, “No.” She had a lot of weight that she [dealt with]; her two sons were missing in action in World War II and presumed dead, and she kept saying, “They’re alive, they’re fine.” It turned out they were at a prisoner of war camp in Germany and were eventually released. So she had a lot of credit. During this [time when] scrutiny and doubt was cast on my future, she said, “He’s going to be famous. He’s going to be famous all over the world. Don’t worry about him.” And that came to pass, and I think that her influence as a woman on me, as a carrier of wisdom and a carrier of our family history, I just had a huge respect for her.

Then my mother, I saw the same qualities in her. My mother was always a positive force in my life, and so it always occurred to me to do whatever I dreamed of doing. And I had three sisters that were really important to me. I actually have good relationships with male mentors in my life, but there’s always women. And as a hirer, I have to admit to a bias. I just relate more to the vision and the spirit that a lot of women bring to big projects. . . .

Tracy is amazing, and as I flounder around, and flail, and bump into furniture and stuff, she’s a steady hand and an encouragement and also calls me out, like, “You don’t get a pass just because you have Parkinson’s. Without your symptoms you’d screw up and do stupid things and be called to the carpet for it.” She’s great at that.

And my daughters are so amazing. My youngest, Esme—and I talk about this in the epilogue—was supposed to go to college. She was supposed to start in university last September, but she saw what was happening, and she had a gap year and pushed it off. So she starts this year. Because she was in the class of 2020 high school, because of the circumstance, there was no prom. But she took it in stride. All her friends that we’ve met, talked to her peers, [they] all kind of say, “It’s a shame we lost all that, but look at what other people lost.” I just was so struck by that attitude. I thought back again about my parents, and thought about how they had been born into the Great Depression and had come of age in World War II, and Esme had been born just a couple months after 9/11, and come of age during the coronavirus. So it’s interesting how life works.