35 minute read

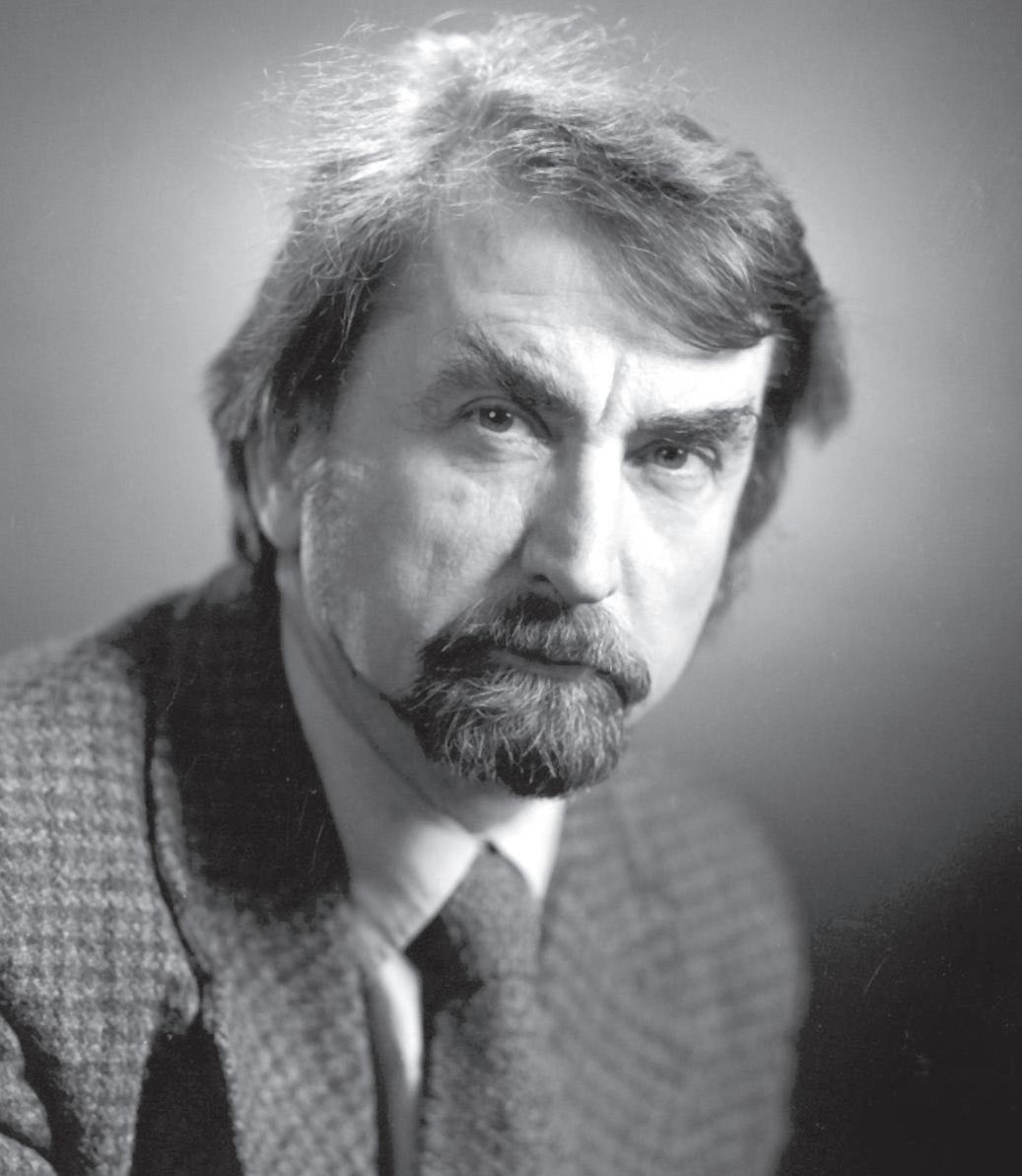

In Memoriam: Roman Kroitor

Remembering Canadian Film Pioneer Roman Kroitor

The Canadian film industry lost a pioneer with the death of filmmaker and IMAX co-inventor Roman Kroitor on Sept. 16.

Born on December 12, 1926, in Yorkton, Saskatchewan, Kroitor produced dozens of films with the National Film Board, including Paul Tomkowicz: Street-railway Switchman, Nobody Waved Goodbye, the Candid Eye series, Giles Walker’s Bravery in the Field, and John N. Smith’s First Winter. His creative partnerships with Wolf Koenig and Colin Low resulted in some of the NFB’s most acclaimed documentaries of all time, such as Glenn Gould: On & Off the Record, Lonely Boy, Stravinsky and Universe.

His collaboration on the ground-breaking multi-screen project In the Labyrinth for Expo 67 in Montreal set the stage for a new era in cinema. Co-directed by Kroitor with Colin Low and Hugh O’Connor, and co-produced with Tom Daly, In the Labyrinth was an immersive cinema experience that caused a sensation at the Montreal world’s fair during Canada’s centennial year. The presentation used 35 mm and 70 mm film projected simultaneously on multiple screens. That process led to the development of the single-projector giant-screen system that helped redefine the possibilities of cinema: the IMAX film system.

Kroitor conceived the idea for the IMAX with cinematographer Graeme Ferguson csc in the autumn of 1967. Their goal was to create the world’s most sophisticated film-projection system. In an interview in the December 2010 issue of Canadian Cinematographer, Ferguson explained that after Expo 67, he and Kroitor realized that there was an audience for large-format films. “It wasn’t just because it was multi-screen. It was because the screens were bigger; because we had more projectors to fill the screens,” Ferguson said. “I was at Roman’s house one afternoon, and he and I were discussing the fact this was a very successful but very cumbersome way to project films. We asked each other, ‘Wouldn’t it be better to have a single, large-format projector to fill a large screen? We talked for about an hour, and within that hour we had sketched out the screen size that could be used and the film format that would be capable of filling it. The idea of a horizontal 65 mm film format with 15- or 16-perf pull across was really worked out in the first few minutes. We said to ourselves, ‘Let’s invent this new medium.’”

Kroitor went on to co-produce the first IMAX film Tiger Child, which premiered at Expo ‘70 in Osaka, Japan.

Ferguson also credits Kroitor with helping to change the way 3D was employed in film with Stephen Low’s 1990 film The Last Buffalo, which Kroitor co-produced with Sally Dundas. “For the first time ever, they showed that 3D could be an art form,” Ferguson says. “And the current 3D boom – which is exemplified by Avatar and some other very good 3D films – really was encouraged by Steve Low and Roman showing the way with that one film.”

Reflecting on his partner, Ferguson recalls: “Roman was always interested in the future. He was always inventing things and picking up things that nobody had tried yet.”

Kroitor is survived by his wife Janet and children Paul, Tanya, Lesia, Stephanie and Yvanna.

By Fanen Chiahemen

hile Ray Dumas csc has spent years honing his craft shooting music videos, short fi lms and documentaries, for his fi rst feature, he wanted a project he could really sink his teeth into as a cinematographer. Then an acquaintance handed him a script for a feature he was producing called I Declare War, and Dumas knew he had found the material he was looking for.

“Once I read the script I fell in love with it,” Dumas says. “The subject matter is a little bit risqué, and the fi lm pushes the boundaries in terms of what the children do and say.”

The risqué subject matter are the war games children play, and not just in the physical sense, but what happens when an everyday game of war between two groups of neighbourhood friends takes an ugly turn and descends into an orgy of betrayal, cruel tricks and crudeness. Written by Jason Lapeyre, who co-directed with Robert Wilson, I Declare War is an honest portrayal of how kids talk and behave amongst themselves.

Unique, too, in the fi lm is that it takes place in real time, that is, over the course of an hour and a half on a hot afternoon in a forest. Yet it was shot in 21 days in Morningside Park, a regional park east of Toronto, and those bounds presented Dumas with his greatest challenge: “How do you sustain an audience’s interest for that long in one location?”

The answer was to opt for a kinetic style of cinematography, keeping the action moving almost all the time. “The kids are playing a game of war, so there isn’t much hanging around,” he says. “So there are very few set-up shots, the camera’s moving constantly. I kept things alive by doing a lot of Steadicam, a lot of jib arm crane shots.”

The secondary challenge was the “busy visual information” the location provided, Dumas says. “With all the leaves in the trees, it becomes a riot of information to the eye; it becomes actually uncomfortable,” he explains.

He therefore decided to forgo wide shots or establishing shots. “We played out this movie almost entirely in close-ups, and the approach was to shoot at an extraordinarily shallow depth of fi eld even though it takes place in the day time. We chose the densest part of the forest so we could shoot low light, and the backgrounds became very soft and dreamlike, very painterly.”

When it came to lighting the dense forest, Dumas adopted the

less-is-more philosophy, focusing on reducing light sources rather than adding them. “We purposely chose the darkest part of the forest so we could control the light rather than letting the sun dictate what was going to happen,” he explains. “Basically, I would always have one large source, a punchy 6K HMI, just to act as the sun and break through the small branches. The rest would be ambient light, and I did a lot of bouncing light off the fl oor to light the actors’ faces.”

The crew also played on the characteristics of the forest to refl ect storyline and character. For example, the section of the forest serving as a base for the squad whose leader has become particularly unhinged is the densest, which meant even at the height of the afternoon there was very little exposure. “So we basically let that play as such and only added basic fi ll to supplement the look,” Dumas says.

The other side of the forest, home to the other team’s base camp, while still dense, is greener and lusher, lending it more of a jungle-like feel. “That was a bit more challenging because I had a lot of patches of bright sunlight. Instead of trying of keep the information in very bright patches of sunlight in the background, I would let them blow out, and it was very effective in giving a dreamlike look,” Dumas says.

About 50 per cent of I Declare War was shot handheld using a Klassen suspender rig (a camera attached to the front of a vest transfers the weight to the hips) giving Dumas, who did most of the camera operating, more stamina. “It affects the way handheld looks,” he says of the rig. “It’s a lot less jittery.” Dumas also opted for two RED MX cameras, as well as his own Cooke Panchro/i lens kit, which he had modifi ed so they would open up beyond the 2.8 T-stop. “They are essentially 2.5, and I had that modifi ed so that when the iris was wide open the bokeh– which is a technical term for the way the leaves in the iris open – was a perfect circle. Because I knew that when I would be shooting wide open, I was going to allow any fl ares to happen naturally, and I wanted those fl ares to be circular and not give away the shape of the iris.”

However, Dumas, as well as the directors, quickly realized that technological tools would only go so far when shooting a fi lm like I Declare War with a group of young actors, most of whom had limited experience, and that restraint would be their biggest asset.

“We all basically agreed that the strongest element of this fi lm was going to be the children’s performances. We didn’t have the budget to create enormous sets or do huge explosions, so we knew that this fi lm was going to succeed or fail based on the performances of the kids,” Dumas says. “And how I dealt with that was I wanted to be, as a cameraman, right in there with the kids, up close. We didn’t do any dolly shots or traditional coverage on long lens. I got very close in with the actors. And being in that much control operating and lighting, I was able to move faster and give the kids the time they needed to get their performance.

“And something really interesting happened when I saw the rushes on a bigger screen at REDLAB,” Dumas continues. “Because we shot in such low light and we were right up in the kids’ faces, the irises in their eyes were wide open. And it makes for a very powerful impact on an audience. It has a very subliminal effect

Left: PK on the hunt. Darker shadow areas and overall desaturation of colour lend an ominous air to the territory occupied by the opposing team. Above: The cast of I Declare War on location in Morningside Park, Toronto.

Photo Credit: Ray Dumas csc

Joker in the green forest.

when you’re standing in front of somebody and their irises are wide open. There have been studies that say that’s what happens when you fall in love. When you’re with a person and you’re talking very close to them and you’re developing a relationship, the iris tends to open right up, and it creates a sense of closeness and connection, and that’s where this fi lm succeeds tremendously. Anyone who watches the fi lm ends up falling in love with these kids. That was the single most successful thing I did on this fi lm.”

Dumas adds that the children were a pleasure to work with, taking direction well and eager to try all suggestions. In fact, being so eager to shoot, they kept the crew on their toes. “The kids were more impatient when we were not shooting. As soon as the cameras were rolling they were gung ho and ready to go,” he recalls.

Helping the production move along quickly was a DI station set up on location in the forest. “We brought in a Da Vinci system so we could look at rushes and set looks right on the spot. That made it very easy,” Dumas says. “We would be watching the rushes while we were setting up the next shot. We were doing basic colour correction on set so when it was edited it already had a very good look to it, and then we just had to go in and massage it. My DIT Kent McCormick [from Bling] gave me a thumb drive that I could bring home with me, play with and then pass back to him to make corrections. I was so fortunate to get him on my set.”

Dumas is quick to also highlight the contribution of his focus puller Michael Bailey, who had “the challenge of having to pull focus under extraordinarily diffi cult conditions – miniscule

Shooting wide open in low light caused the pupils of the children’s eyes to dilate in close-ups, creating a powerful subconscious connection with the audience.

depth of fi eld, moving cameras, and child actors.”

Bailey agrees that focus pulling was a particularly diffi cult task on I Declare War, which premiered at the 2012 Toronto International Film Festival and won the audience choice award at this year’s FantasticFest in Austin. “We would do loose blockings, but no one was ever really tied to marks,” he recalls. “There wasn’t a formalized structure to how the shots would play out. I tried to pull a lot by eye, especially with Steadicam shots. I would take tape measurements and try to pull by eye as best I could.”

Dumas goes so far as to say, “Without Michael we would not have had a movie. The forest would get so dark by the end of the day that I would have to switch over to Zeiss high-speed lenses – an older set of high speed that go to 1.3 – just to have enough light to shoot. And when we were doing moving Steadicam shots at a T 1.3 Michael might have had a depth of fi eld of an inch, which meant he would have to choose which eye would be in focus on the actor. And what he did was nothing short of a miracle,” he says.

The premise of this project was to intersperse the interviews with the veterans – some of whom were telling parts of their story for the fi rst and possibly last time – with visualisations of their stories in a way that would convey the real fi repower and resulting horror, fear and tragedy of war. If a veteran recalled that he had been hiding in a house when a V2 rocket landed on a church opposite, we would faithfully recreate this setting and use the same type of explosives. When a building blew up, the audience would be able to see a realistic result rather than a movie pyro effect or CGI. Channel 4 Specialist Factual Commissioning Editor, David Glover, explains that the series uses “actual demonstrations rather than reconstructions. It is a radical approach to bringing historical testimony to life.”

Pre-productionPre-production

I came on board for the visualisations which were all set up and shot in Canada. For this part of the production a suitable site where huge explosions could be safely set up and executed was sought. A large military base in New Brunswick where major explosives testing is carried out was located. Here, we could build sets without fear of hurting or disturbing anyone.

Before the main shoot started, the producers cut a three-minute teaser to convey the style of the programme and showed this to the base commander and a Canadian government representative for veteran affairs. They were both very moved by this and appreciative of the way in which we would be using cutting-edge technology to tell the stories in a new way, especially to younger audiences, in order to enhance understanding of what these people had been through.

The project was very collaborative and well planned. We had to think about everything from camera/personnel housings and lens protection to cabling. So from February to June 2011 there was much discussion between myself, Crispin Reece, the director, and the British and Canadian production teams, with pictures, information and feedback from prototype tests being bounced backwards and forwards.

Quite apart from the obvious safety considerations, many of the

Image from Canon 5D POV mounted on gun.

Britain ’ s Channel 4 series World War II: The Last Heroes represented a powerful and novel way of bringing history to life. Latest generation slow-motion cameras and lenses were employed to capture in evocative detail the detonation and impact of real explosions of the same size and power of those actually experienced in World War II. Illustrating a series of moving interviews with aged Allied veterans, the explosions supplemented rare historic footage to tell the reallife stories of the survivors. Co-producers Impossible Pictures in the United Kingdom and Entertainment One of Canada approached director of photography Jeremy Benning csc to lead the camera team, and here he explains how they went about capturing these highly charged sequences.*

Photo Credit: JeReMY BennInG

Camera operator Jason Vieira readies the Phantom Gold in its blast housing.

Photo Credit: JeReMY BennInG

Jason Vieira and Ryan Acker lift the camera blast housing onto the tripod.

Landing craft takes a direct hit from underwater mine.

set-ups literally could not be repeated – most of what we were shooting was going to be blown to smithereens, and in some cases we would be using genuine World War II vehicles that could not be replaced. We were very aware that we couldn’t just show up and hope that this worked!

out of harm’s way

Crew safety was paramount. There were bomb shelters for the crew and a team of specialist explosives experts to advise on how to keep both ourselves and the equipment safe at all times. For each set-up the precise amount of explosives and resultant risk were calculated and the appropriate precautions put in place.

Much thought was given to the best ways in which to protect the cameras while leaving them relatively easy to operate. After researching the housings available on the market, we decided we were going to have to make our own. Max MacDonald, our special effects expert, was able to advise on exactly the strength of blast these were going to need to be able to withstand. The housing we developed comprised a metal tube that opened in half so that the cameras could be adjusted. The end product wasn’t a thing of great beauty but it provided a very effective combination of protection for the gear and usability. None of the main camera gear was damaged, which is quite remarkable considering

Did you know? BOKEH “ Bokeh ” (from the Japanese “ boke ” meaning “ blur ” or “ haze ” ) is the blur, or the aesthetic quality of the blur, in the out-of-focus areas of an image or, more specif ically, the way the lens renders out-of-focus points of light. Differences in lens aberrations and aperture shape cause some lens designs to blur the image in a way that is pleasing to the eye, while others produce blurring that is unpleasant or distracting good’ and ‘bad’ bokeh, respectively. Bokeh occurs for parts of the scene that lie outside the depth of f ield and is often most visible around small background highlights, such as specular re f lections and light sources. However, it is not limited to highlights and can occur in all out-of-focus regions of the image. the size of the blasts, some of which involved as much as 400lbs of explosives.

It wasn’t just the camera and lenses that needed safeguarding – great attention was paid to protecting the long runs of cables involved and, again, no cable was damaged in the entire shoot. Sim [Digital] helped custom-build a fi bre optic cable system that allowed us to connect to the cameras from a much longer distance than normal (for some set-ups as far as 600 or 700m). For heavy shrapnel blasts at close range to the cameras, we protected the cables with sheets of 3/4” plywood laid on top, and then rubber carpets at further distances. This often meant laying down a couple of hundred metres’ worth of protection.

One of the main problems of enclosing the camera in a metal tube for long periods in the Canadian summer would be overheating. The metal housings were painted white on top to defl ect the sun, plus the camera’s internal thermal sensor could be monitored remotely, and a fan was included in each housing.

Very high speed Very high speed

We shot for 17 days, recording several events each day with four Phantom cameras; two Gold and two of the newer Flex model that can record up to 2500 frames per second. Recording was to HDCam decks. On an earlier pre-shoot in the winter, we had used a Weisscam HS-2 from P+S Technik, also a good camera, but for the main shoot we found that it was not possible to control the Weisscam from far enough away and so, after testing various models, we opted for the Phantoms. We also used GoPro minicams to get in closer to the action and, for some sequences, played with unusual viewpoints, for instance, mounting a Canon 5D on the end of a machine gun to achieve spectacular POV shots running through the undergrowth, looking down the barrel of the gun towards the muzzle fl ash.

A major challenge of the shoot was the triggering of the camera’s capture mode. With the extreme frame rates involved, the maximum capture time was just 4 to 8 seconds, so the cameras had to be triggered immediately before the blast. If incorrect, we’d miss the start of a blast. We controlled the cameras from laptops in the safety of the military’s personnel bunkers and we took full advantage of the Phantom’s customizable pre-trigger times.

For the lenses, I went straight for Cooke 5/i and Panchro/i prime lenses. I have always used Cookes and purchased my own set of Panchro/i lenses last year to shoot Afghan Luke, a feature fi lm about the aftermath of the war in Afghanistan. I really wanted to capture these moving stories with the best lenses available and I have always loved the “painterly” look of Cookes.

What I mean by painterly here is the way Cooke lenses handle focus fall-off, blurred backgrounds (“bokeh”) and contrast. This way of defocusing out-of-focus areas of the frame is part of the signature “Cooke look.” Cooke has a way of making sharp yet gentle images with their optics. The resulting images are velvety and smooth with a shallow depth of fi eld that leads your eye to the subject, bringing a naturalness to each scene. For this series, I wanted the viewer to experience the scene as a sympathetic witness rather than as if watching a scientifi c explosives test. This look would also help the linking from archive footage to the interviews and reconstructions.

On set I dialled in a contrasty, desaturated look to our monitors to allow us to preview the fi nal graded look while the Phantoms captured the full range of colour and contrast. This allowed the colourist to have all the information needed to push and pull the image in the fi nal grade.

The precious lenses were protected with a form of Perspex polycarbonate called Lexan; we would have preferred glass but had to accept that plastic was the most protective. Tests with different thicknesses were conducted, and at all stages we had to defer to the explosives experts – when you’re dealing with metal shrapnel fl ying at 22,000ft per second, you go with what will protect most effectively! Lexan can be bulletproof so we were able to put the lenses into serious harm’s way without worrying (well, not too much). Shooting through a piece of plastic obviously meant some optical degradation, but with these high-performance lenses we didn’t lose too much detail.

At times, set-ups were almost like shooting still life; we would frame a composition with a beautiful shot of a church, then this would begin to shatter in extreme slo-mo, creating a contrast of serene horror. The human presence is implied; the viewer knows there are people in the church or in the landing craft from details like a knapsack on a wall or boots drying in the sun, a helmet fl ying through the air – little details that bring home that there were people involved in these horrifying situations. It’s all in your mind. You don’t need to see the people – in some ways it is scarier not to.

Fireballs and f lashes Fireballs and f lashes

We shot largely wide open to capture the blasts and fi reballs, using only available light. Some of the incendiary bombs were shot at dusk to take advantage of the last vestiges of daylight before the set was lit up by the bright explosions of magnesium and phosphorus sparks, the fi reballs creating their own light sources. Exposure was set manually on the Phantoms and I relied on Sony OLED PVM-740 monitors, viewed from the safety of the shelters, for confi dence in this. Generally I erred on the side of being slightly under to avoid burnt-out skies or over-blown fi reballs and also used ND graduated fi lters to control bright skies. Setting exposure was mainly down to experience and knowing the latitude of the Phantoms to gauge how they would handle the bright bursts of light.

We also had to deal with extreme contrasts; direct transitions from fl ashes of bright light and fi reballs to heavy black smoke. Again the Cookes coped with this brilliantly without any double imaging or ghosting.

Most of the explosions were shot at 1000–2500fps; viewing this amount of power at these frame rates was incredible – you see the shock wave, the dust rising, things you would never see with the naked eye.

heavy work heavy work

This was a physically demanding shoot. There were seven of us on the team who did everything from dealing with the cables for each shot to moving the heavy housings – it really was an “all hands on deck” project. In order to provide the stability and protection required in the face of the massive explosions, the assembled tripod/housing units weighed in at 300lbs, which provided a signifi cant challenge when it came to moving them around. In fact, with all the obvious hazards present, the only injuries resulted from handling the camera housings. We all knew this was a one-off opportunity and everyone pitched in, knowing the results would be worth it. The evocative series that has resulted is testimony to this.

2 x Phantom Golds 2 x Phantom Flexes KIT LIST 1 x Weisscam HS-2 1 x Set of Cooke 5/i T1.4 lenses (25, 32, 50, 65, 75, 100) 1 x Set of Cooke Panchro/i lenses (18, 25, 32, 50, 75, 100) 1 x O’Connor 2575 f luid head 1 x O’Connor 2060 f luid head 4 x Sets of Tiffen ND soft grads 4 x Schneider in-tray rota Polas 2 x Sony PVM-740 7.4” HD OLED monitors 2 x Panasonic 1760 17” LCD monitors 6 x GoPro Hero cameras 1 x Canon 5D MKII 1 x Set of Nikkor AIS primes 1 x Fotodiox Nikkor to Canon lens mount adapter 1 x Small HD DP-6 monitor 1 x Transvideo CineMonitor HD6 SBL 6” LED backlit monitor 2 x ARRI LMB-5 matte boxes 2 x ARRI LMB-15 matte boxes 2 x Sony HDCam S280 portable recorders 4 x 800 metre rolls of Telecast f ibre optic cable

This article was f i rst published in Zerb, the journal of the Guild of Television Cameramen www.gtc.org.uk/publications/zerb.aspx. See more about the GTC at www.gtc.org.uk.

LIGHTING A VIRTUAL APOCALYPSE: Samy Inayeh csc Talks Cybergeddon

By Fanen Chiahemen

Set in the world of cyber-terrorism, Internet identity fraud and computer hacking, the digital crime thriller Cybergeddon follows an ambitious young FBI agent who heads up a task force that monitors and prosecutes those who use the Internet for negative ends, unleashing chaos on global fi nancial government structures.

Cybergeddon is the brainchild of CSI: Crime Scene Investigation creator Anthony Zuiker; the other big name attached to it is actor Olivier Martinez (Unfaithful, Taking Lives). Aside from having star power, it also has a fi rst-of-its-kind distribution model, being released in 10-minute instalments on Yahoo! over nine weeks in 25 countries.

Director of photography Samy Inayeh csc – a Dubai-born Torontonian – says he and Venezuelan-American director Diego Velasco were conscious of the fact that Cybergeddon was likely to be viewed not just on widescreen computer monitors and bigscreen TVs, but also on mobile devices, which set the foundation for the way they shot it.

“We both knew that at its best it would be seen on a big-screen TV and at times in a movie theatre, and at its worst people would be watching it on their iPads or even their iPhones,” Inayeh says. “We were making a fi lm that could potentially be watched on lunch breaks or on a bus on your way somewhere, so it had to be always moving and always energetic and always sustaining interest visually.”

Velasco elaborates, “Because the fi lm is going to be viewed on

An action scene from Cybergeddon.

computer screens, iPhones and iPads, we wanted a style that’s bold, colourful and aggressive yet grounded, so people feel like what they’re watching is real and feel like whatever happens to the characters can happen to us.”

However, the producers also wanted a fi nal product that would stand up on the big screen. “They always maintained that they wanted something that didn’t just feel like a TV movie. They wanted something that if they were watching it in a theatre it would still look good. So lighting-wise I lit it essentially like a motion picture that was intended for the big screen,” Inayeh says.

The trouble was he had to achieve the desired look without an arsenal of slick tools at his disposal. “The misconception was that because Anthony Zuiker was involved and it was being fi nanced by big companies like Yahoo! and Norton we had more money than we actually did,” the cinematographer says, laughing. “In fact our lighting budget was smaller than budgets I’ve had on even smaller projects. The money went very quickly to the large cast, to the amount of stunt sequences and action sequences, and the amount of sets and locations that we had.”

Fortunately, he was working with a director who has a background as a cinematographer. “My experience coming up through the camera department really allowed me to be very effi cient and to save a lot of conversations, and Samy and I could

just look at each other and know exactly what we’re thinking and cover scenes in a very effi cient way,” Velasco says.

Both knew that lighting effi ciently would mean being creative with existing light. “We would just strategize,” Inayeh explains. “We would frame the action in such a way that we knew we would already get a lot of support from what was existing by shooting at the right times of the day or taking advantage of streetlight and

existing artifi cial light often just supplementing it slightly or subtracting it. We could actually get a lot more bang for our buck that way. We said no to lighting if we didn’t have time for it. Or we would go to a location and instead of putting lights on we would turn lights off, and in the end we were able to get that aesthetic.”

To capture the light, Inayeh, who comes from a fi lm background, relied on the ALEXA because of its latitude and sensitivity. “I had a really strong idea of what I could get away with, having shot a lot of commercials and music videos with that camera,” he says. “Often times we’d just be shooting out on the street with nothing but an LED brick light, and we’d be able to see for miles. And we’d get these perfectly beautiful images where it probably looked like we’d spent a little extra time and effort lighting it.

“One time we had a very big scene that we were shooting in a library. In the scene, two of the main characters walk in from the bright sunlight outside. They walk around the corner to a big foyer and then into a library with 30-foot high ceilings and large windows. Everybody was panicking at the beginning of the day because we were running out of time. So using a couple of really strategically placed key lights and relying on the robustness of the ALEXA’s image and latitude, we were able to do this page-and-a-half scene where they come from really bright light, go through a dark foyer, then go into a much brighter room. I was able to light it in 20 minutes, in one single beautifully executed Steadicam shot, pulled off by the always great Mike Heathcote, and have it come out wonderfully.”

By keeping the camera moving and getting copious amounts of coverage, Inayeh was able to create a visual language that was dynamic, bold and fast-paced. Two ALEXAs ran alongside each other for almost every shot of the fi lm, with some strategically placed digital SLRs and Go-Pros thrown in for action and stunt scenes. “Often times it would be a very hectic camera department. Our fi rst ACs Rob Tagliaferri and Jurek Osterfeld did a wonderful job of keeping the departments organized, pulling off super tricky shots and keeping me laughing,” Inayeh recalls. “There were days where we would have fi ve or six cameras running on a given scene. It was a challenge in that way. I’d had enough experience with digital SLRS to know we could get the images to a place where they looked nice enough or clean enough to cut rather seamlessly with the ALEXA footage.”

Inayeh was also impressed with the 45- 250 Zeiss Fuji Alura zoom lens. “It was beautiful. We pretty much lived on it on B camera. I was surprised at how good the glass was, how sharp and good the tracking was, and how good the colour rendition and contrast was.”

Working with a director who liked to take risks pushed Inayeh to ignore some of the traditional rules of shooting. “Diego was always looking for new ways to look at things and cover the action and place the camera,” Inayeh says. “He never wanted anything to be the same or conventional. He almost never wanted to do a master.”

Olivier Martinez in a scene from Cybergeddon.

Inayeh recalls Velasco’s ingenuity in one scene that required an establishing shot of police cars racing into a building: “We were hunting for a place to put the cameras to cover the action. And then Diego had this wonderful idea of, ‘Why don’t we just put the camerain the back seat of the third police car?’ So I got into the back seat with the camera and the stunt driver. We tore off down the street with the ALEXA, stripped down to a battery and a lens, in the back of the car. We came tearing up in front of the building, and my A cam operator Mike Heathcote, who was brilliant, was hiding behind a tree. So as the car comes up, he runs out and opens the car door. I’d lean out and he would grab the camera and he would go running into the building with the police offi cers. We didn’t do any other coverage of that sequence. We didn’t do a wide shot of the building, we just did that one shot that was so full of energy and life. That was the third day of fi lming, and at that moment I looked at Mike and said, ‘This is how we’re going to shoot the rest of this movie.’

“We were always encouraged by Diego,” Inayeh continues. “If this would be the obvious way to light it, we had to say to ourselves, ‘Let’s work against the way we’ve been trained or conditioned. Or the way we’ve seen things done already.’ And every time we did a take, Diego would say from behind the monitor, ‘Give me something different, give me something else.’ Sometimes we would do 20-minute takes and just keep resetting in the middle of the take. So we never had a moment to relax or fall into a sense of complacency in terms of the visual style. And we always had to be alert and thinking, ‘Okay this shot’s going great, but Diego’s bored already so when he calls reset he’s going

Technicolor On-Location, supporting your vision from set to screen

technicolor.com/toronto twitter.com/TechnicolorCrea technicolor.com/facebook

Grace Carnale-Davis

Director of Sales and Client Services 416.585.0676 grace.carnale-davis@technicolor.com

to want something different.’ It was very challenging and tiring and very invigorating. A lot of the fi lm was shot handheld too, so it was a very physically challenging shoot.”

Inayeh credits the support of his crew for being able to pull it off. “Everybody rose to the occasion. My gaffer Chad Roberts and my key grip Anthony Police were always up for it and kept an eye out for me while trying to keep up with a really fast-paced schedule. “The focus pullers, Rob Tagliaferri and Jurek Osterfeld, were amazing, as was my second unit DP Michael Jari Davidson,” he says.

When it came to watching dailies, Inayeh had two rotating drives he would watch ProRes QuickTime fi les on. “It became very clear that operating on the fi lm, as well as lighting for two cameras all the time, and trying to light sets ahead was daunting for me. I was on my feet all day from the minute I showed up on set to the minute I went home, I never had a chance to sit down,” he says.

Producer Anthony E. Zuiker and actress Missy Peregrym on the set of Cybergeddon in Toronto.

Fortunately, he had what he calls “a remarkable and incredibly talented” DIT in Baha Nurlybayev. Because Inayeh didn’t have very much time to spend with him, Nurlybayev “would create looks and then he would come to set and fi nd two minutes where I would be sitting on the dolly and not have a camera in my hand, and show me the stills on an iPad of the shots he was working on. And I’d scroll through the stills really quickly and give him quick, rapid-fi re notes of what I wanted changed and how I wanted them to look. And he never fell

behind and he always managed to get the dailies looking the way I wanted them to. It’s not ideal, but it worked and that’s the way we needed to approach things on this fi lm, for sure.

“Every day we’d look at the dailies and go, this is looking cool, this is looking like a movie I’d want to go see. It’s got a more artistic feel to it for an action fi lm. It’s a spare, simple, yet beautiful looking fi lm,” he says.

Cybergeddon is available online at yahoo.ca.