NOT ENOUGH

Despite on-campus drug use increasing, Narcan accessibility remains low.

Read on page 2

NARCAN NECESSITY

Student research shows drug use at LSU higher than previously thought

BY CROSS HARRIS @thecrosharrisA survey conducted by a group of LSU capstone students this spring revealed rates of drug use were much higher among the LSU student body than previously thought.

The capstone group also discovered access to the life-saving opioid overdose drug, Narcan, lacking on LSU’s campus.

The survey, created by five seniors for a political communications class, found 70% of respondents knew another student who used Adderall or Vyvanse without a prescription, with 57% of those respondents saying they knew someone who used the drugs frequently or very frequently.

Sixty two percent of respondents knew another student who used cocaine, with 46% of those respondents saying they knew someone who used it frequently or very frequently.

And 86% of respondents knew another student who used marijuana, with 75% of those respondents saying they knew another student who used it frequently or very frequently.

The capstone group found students wanted access to Narcan, but couldn’t find it on campus: 82% of survey respondents were interested in being trained to administer Narcan, but 96% of students had never seen it anywhere on campus.

The survey reached nearly 1,000 students from all grade levels and most of LSU’s colleges.

Three of the capstone researchers, Gabby Jensen, Ryley Young and Rachel Wong, spoke with the Reveille about their group’s survey—and the university’s reaction.

How it started

Young said the capstone project was born from the group’s personal experiences.

“I think we hear a lot about the fentanyl crisis, we see drug use in our, you know, interpersonal relationships and lives,” Young said. “And it felt like a place that maybe we could recognize LSU had the potential to do more, and then also should probably be doing more.”

The group began by diving into the data.

In correspondence with the East Baton Rouge District Attorney’s Office, they learned the state of Louisiana had much higher overdose death rates than the national average.

In 2023, the national overdose death rate was just above 30 per 100,000 people, according to data from the D.A., Louisiana’s fatal OD rate in 2023 was just under 50 per 100,000, and East Baton Rouge Parish saw OD deaths at about 65 per

100,000.

In a hard-hit parish, in a state with increased rates, in a country experiencing an opioid epidemic—the capstone students wondered how LSU’s drug policy stacked up against other universities.

“The more we looked into it,” Jensen said, “the more we realized that LSU really was lacking.”

In their research, they found other schools dealt with the problem by providing information on and access to Narcan.

But in LSU’s online presence, the only mention of the lifesaving treatment came from a short release by the LSU Police Department and the university code, prohibiting drug use on campus, Wong explained.

Narcan is available on LSU’s campus from three main sources: the Student Health Center, the LSU Police Department and in the university’s dorms.

Typically, resident advisers on LSU’s campus are trained on how to use Narcan in the event of an emergency. But when the capstone students visited dorms, they found some R.A.’s weren’t familiar with the drug; others had been trained, but didn’t know where to find their dorm’s supply of Narcan.

“It shows there’s a lack of information around what the action plan would even be,” Jensen said.

LSU has an action plan for fires, Jensen reasoned, and an action plan for when someone has a heart attack, where to find an automated external defibrillator, or AED. But LSU’s action plan for overdoses just wasn’t there.

“This was not something that the university is necessarily prepared for,” Jensen said.

Why were other schools putting so much effort into increas-

ing Narcan accessibility, when data showed that Louisiana, and Baton Rouge specifically, had much higher overdose rates?

“One could argue that it’s out of care for their students” that other colleges are making Narcan more accessible, Jensen said, then paused to clarify: ”Not that LSU doesn’t care, but that maybe they need to take more steps.”

The group couldn’t make sense of the high drug use but limited access to Narcan they saw in the LSU community.

“We knew it was affecting our campus,” Wong said, knitting her brow, “and we wanted to take that to the next level and try to fix it.”

Making the survey

LSU’s Institutional Review Board is the organizing authority on campus that makes sure research involving human subjects complies with federal requirements. Anyone who wants to conduct a study that involves people is required to get approval from the IRB before starting.

Wong had already taken a certification course through the IRB for past projects. She recertified, then helped the capstone group submit its survey to the IRB for approval.

The student group worked with the IRB to address areas of improvement in the survey. Then, in late February, the capstone group got its go-ahead with a letter from the IRB approving the study.

The student researchers said they tried to construct their survey to encourage responses that were as truthful as possible.

“People might be nervous to admit to using drugs, even if we’re saying it’s an anonymous survey,” Jensen added.

So the capstone researchers

B-16 Hodges Hall

Louisiana State University Baton Rouge, La. 70803

NEWSROOM (225) 578-4811

formed questions they thought would compel more candid answers. Their survey asked respondents if they knew other students who used drugs rather than if they themselves used, hoping it would quell fear of potential legal repercussions.

In a 2023 survey conducted by LSU administration, 28.7% of students said they had used marijuana in the last 30 days, and only 1.6% said they had used cocaine in the last 30 days. But the capstone group participants said they believe the questions in that survey may have discouraged students from answering candidly by asking them directly if they used drugs.

“I think that if you ask 100 college students if there’s a drug problem on this campus, you’re probably gonna get answers that side a little bit more with what our board says, rather than theirs,” Young said.

The capstone group also tried to position their survey to be as representative as possible, Jensen said: The survey’s respondents are spread evenly across academic year and college.

“And it wasn’t by convenience,” Wong said. “We had to email professors. We had to reach out to Greek chapters to try to visit. And we made efforts to make sure that it was a representative population.”

The students corresponded with Manship School Dean Kim Bissell to get contacts for every student in LSU’s college of mass communication.

They also coordinated with LSU’s Student Health Center, from learning about Narcan access on campus to consulting the center’s drug use task force on how to construct their study.

“The Health Center praised

ADVERTISING

(225) 578-6090

Layout/Ad Design BEAU MARTINEZ

Layout/Ad Design SAMUEL NGUYEN

CORRECTIONS & CLARIFICATIONS

The Reveille holds accuracy and objectivity at the highest priority and wants to reassure its readers the reporting and content of the paper meets these standards. This space is reserved to recognize and correct any mistakes that may have been printed in The Daily Reveille. If you would like something corrected or clarified, please contact the editor at (225) 578-4811 or email editor@lsu.edu.

ABOUT THE REVEILLE

The Reveille is written, edited and produced solely by students of Louisiana State University. The Reveille is an independent entity of the Office of Student Media within the Manship School of Mass Communication. A single issue of The Reveille is free from multiple sites on campus and about 25 sites off campus. To obtain additional copies, please visit the Office of Student Media in B-39 Hodges Hall or email studentmedia@ lsu.edu. The Reveille is published biweekly during the fall, spring and summer semesters, except during holidays and final exams. The Reveille is funded through LSU students’ payments of the Student Media fee.

NEWS

LSU overpaid some R.A.’s up to $575 — and now wants it back

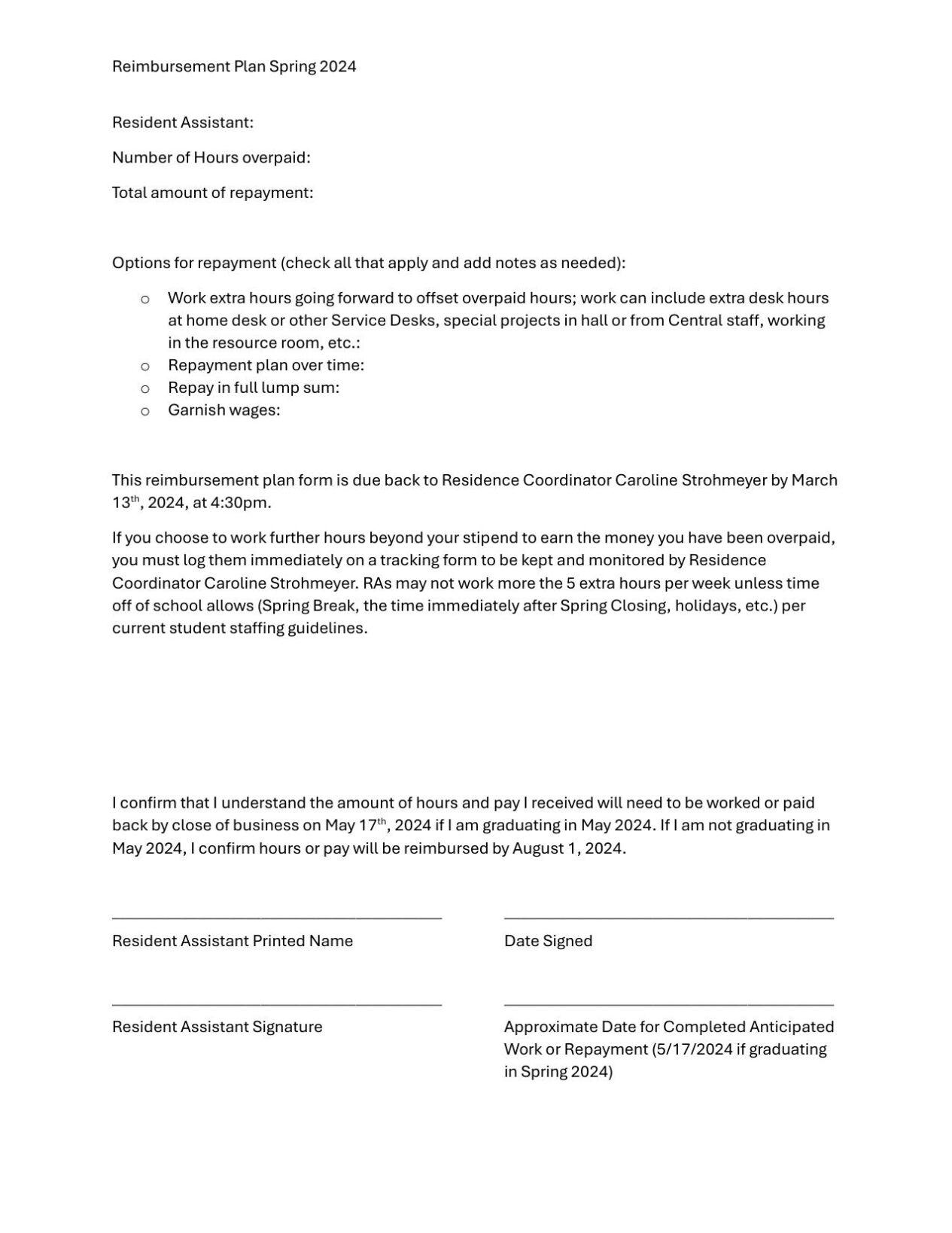

BY MADDIE SCOTT @madscottyyLSU overpaid 14 residential assistants in the Horseshoe dormitories between $200 and $575 and is requiring them to pay back the money or work additional hours.

“After reviewing fall semester payments to RAs who work in the Horseshoe, we discovered that some of the RAs were paid twice for some of their desk shifts,” said Catherine David, the associate director of communications and development of Residential Life, in an email statement to the Reveille.

The R.A.’s learned of the scenario and their options for repayment through their direct supervisor and two members of the departmental leadership at their weekly staff meeting on March 6, David said.

The R.A.’s were required to sign a contract due back to the residence coordinator a week later on March 13. The Reveille acquired the contract through a public records request, which is pictured below.

While R.A.’s were given the option to work additional hours, they aren’t allowed to work more than five additional hours per week. Graduating R.A.’s had until May 17 to accumulate the funds, and nongraduating R.A.’s have until Aug. 1, according to the contract.

DRUG RATES, from page 2

our survey, they encouraged us to go out and collect information, and then they also greenlit our questions before we asked them,” Young said.

Then, when the students presented their findings back to Health Center representatives, they heard positive feedback.

“They did an amazing job,” the Director of Wellness and Health Promotion Michael Eberhard said in an email to the capstone group and officials from the Health Center.

In another salutary email, Assistant Vice President for Student Health & Wellbeing Dan Bureau called the survey a “need.”

Jensen said representatives from the Health Center told the capstone group they had a feeling there was a problem on campus, but without concrete data, it was hard to begin addressing that problem.

The student researchers hoped their survey could be that concrete data.

Making a difference

As the group learned more about the prevalence of drug use and the lack of Narcan access on campus, Young said he began to think of their project as a tool for, hopefully, shifting the LSU perspective.

“Narcan isn’t simply an emergency response that a police

David said all R.A.’s received a raise last year related to their stipends.

“With that raise, we restructured RA responsibilities to include working 4 hours of their average 20 hours a week at one of our departmental service desks,” David said. “Those four hours that are worked every week are paid through the RA stipend payments. Unfortunately, we discovered that a small number of our RAs were also paid hourly for those four required hours during fall semester resulting in a double payment.”

An R.A.’s perspective

Greg, a Horseshoe R.A. affected by the overpayment, told the Reveille he was disappointed in the situation. He spoke to the Reveille on the condition of anonymity to protect his employment and is being referred to by a pseudonym.

Greg said the overpayment occurred because the supervisors promised the R.A.’s a raise if they worked four additional hours per week behind the Evangeline Hall front desk. The R.A.’s asked their supervisors if they needed to log the hours, to which they were told yes, Greg said. At the March 6 meeting, the supervisors told the R.A.’s that they were logging their hours incorrectly.

The overpayment occurred because the hours were already included in the R.A. stipend, but the

officer should give or a nurse in the Student Health Center,” Young said. “It can be a preventative one that you can easily equip students with if you have the ability to.”

Young and his team partnered with the Student Health Center to hand out free Narcan on LSU’s Free Speech Alley on two occasions this spring. They were able to get funding through a pre-existing grant from the LSU Board of Supervisors.

The free Narcan didn’t last long. On both occasions, the capstone researchers found students were eager to take advantage of the access, and within a few short hours all their Narcan had been given away.

To Jensen, Young and Wong, their survey felt like proof of what they already knew: that more LSU students were using drugs than it seemed. That more LSU students wanted access to Narcan.

Through their school project, the capstone students had become accidental experts— and intensely passionate about the emergence of student drug use.

“Our mission at the end of the day was just to help these students,” Wong said.

In the media and LSU’s response

The capstone researchers first shared their findings with

supervisors instructed the R.A.’s to still log them, Greg said.

“I feel disappointed in the fact that as RAs we do so much for the community in ensuring that residents are receiving the resources and support they need to make their first-year experiences as best as possible.” Greg said.” And to have a supervisor sit in the room with us and fail to take accountability for her mistake made me disappointed in residential life.”

A lawyer’s perspective

Employment attorney Robert Landry said accidental overpayments are not illegal, and employers have the right to follow up and ask for the money back, he said. If there was malicious intent and the money was kept, then it would be illegal.

“Things happen in the workplace,” Landry said. “People get overpaid. People get underpaid. Generally, it gets worked out.”

The National Labor Relations Act gives private employees the right to talk about terms and conditions of employment, Landry said. Because R.A.’s are public sector employees, it isn’t illegal for the supervisors to ask the R.A.’s to not gossip or talk about the situation.

“It does not cover public sector employees,” Landry said. “So that would be, you know, employees of state, federal and local governments and their subdivisions.”

news outlets in early April. WBRZ reporter Nicole Marino wrote an article explaining the survey and the students’ mission to increase Narcan access on campus. Marino is also an LSU journalism student and reporter for the student-run TigerTV.

In the following days, WBRZ received emails from LSU’s Vice President of Marketing and Communications, Todd Woodward. One email arrived with the headline: “Poor Journalism.”

Woodward wrote that LSU did not have a drug problem, adding that there was no correlation between the non-opioid drugs included in the survey questions and Narcan, the opioid overdose drug.

Upon learning of the emails, the capstone students pointed to the fact that many people don’t intend to ingest the opioids lacing other drugs.

“All data points to the fact that most overdose deaths are happening because of accidental overdose, because people do not know that it’s in their drugs,” Jensen said.

In his emails to WBRZ, Woodward wrote that the story bordered on defamation and that the student survey was “faulty data.”

“I’ll check in with our lawyers next,” he concluded.

Shortly after, WBRZ published another article detailing the interaction.

The student researchers’ professor, Bob Mann, voiced his support in response.

“They [the capstone group] love this place and they are concerned about the well-being of students in a way that I’m afraid some administrators aren’t,” WBRZ quoted Mann, “so I’m really proud of them for speaking truth to power.”

Young told the Reveille he was shocked by Woodward’s emails, especially because the university had made no efforts to reach out to the capstone group to learn more about how the survey was conducted.

“You can say that there’s not a problem,” Young said intently. “But no one’s watching to see what’s going on.”

The Reveille interviewed Woodward over the phone in the weeks following his email exchange with WBRZ. His attitude toward the survey had shifted markedly, though he still took exception to both the student research and WBRZ article.

Woodward said he thought Marino’s story ought to have included LSU’s own drug-use figures for comparison against the new data.

He also took issue with the survey’s methodology, saying he thought it may have skewed the results. Instead of asking respondents if they used a particular drug, the new survey asked respondents if they knew

another student who did. Woodward argued that just because 1,000 respondents know, for example, someone who smokes cigarettes, doesn’t mean that there are 1,000 people in a sample that light up. There could be overlap, he said.

But above all, Woodward said that LSU’s policy decisions weren’t up to him.

“I’m the marketing guy,” he said.

“Regardless of the source,” he had mentioned earlier, “it’s my job to protect the brand of LSU, to say, I think you’re looking at bad data,” he said, referencing the disparity between LSU’s own conclusions and the student survey’s findings.

On a somewhat conciliatory note, he said that if the student researchers wanted to see change on campus—an awareness campaign on the dangers of illicit drugs, or a conversation about increased access to Narcan—then he thought the LSU administration would be open to that.

Woodward also conceded that, despite his misgivings with most of the student data, he agreed the capstone researchers had proven LSU students want greater access to Narcan.

A meeting with LSU’s higherups In the final weeks of LSU’s

DRUG RATES, from page 3

Spring 2024 semester, members of the capstone project met with LSU’s Vice President of Health Affairs Courtney Phillips and Vice President of Student Affairs Brandon Common. Hot on the heels of the WBRZ-Woodward kerfuffle, the student researchers discussed their hopes for how the university could change its Narcan policy.

“I think it was a pretty productive meeting,” Jensen said.

The student researchers explained to the two VP’s how their capstone assignment had evolved into a passion project— and their dismay when they learned that another student journalist, Marino, had received backlash for her reporting.

Despite that initial response, Jensen said that in the meeting with Phillips and Common, she felt the two VPs were receptive to the survey and willing to do something about improving Narcan access on LSU’s campus.

For next steps, Jensen said the capstone students had suggested stocking Narcan next to campus AED’s, or at the very least having one dose, in a highvisibility area, in each building.

For her part, Jensen said she’d be checking in to make sure that LSU moves forward on improving their policy. Jensen also said two of her fellow

group mates, Cameron Lavespere and Rachel Wong would be at LSU’s law school next school year and that they’d also be continuing talks with the administration.

“We’re going to make sure that this is happening,” Jensen said.

Narcan access at other SEC schools

BY CROSS HARRIS @thecrossharrisColleges throughout the SEC have online resources dedicated to informing their students on what Narcan is and how to use and access it. Some, like Texas A&M, have task forces dedicated to preventing opioid deaths. Others are giving away Narcan for free.

At the University of Alabama, Texas A&M, the University of Florida and several other schools, webpages outline how students can access free Narcan.

“It is important that all students and community members carry Narcan,” reads the UA webpage on Narcan. “Even if you do not use opioids, or have knowledge of anyone using opioids around you, the continued rise in overdose rates necessitate more civilians carry Narcan in order to prevent overdoses across the nation in the future.”

The University of Kentucky has a section on their Narcan webpage where students can learn about the state’s Good Samaritan laws, which provide legal leniency for people who contact the authorities when seeking medical care in the event of an overdose.

Other schools have installed overdose kits throughout their campuses. A new law in Arkansas required higher education institutions in the state to keep Narcan on their campuses and keep a record of every dose. Now, the University of Arkansas has 541 Narcan kits throughout its facilities.

Out of the 13 major universities in the SEC, LSU is among the few doing little to nothing to improve awareness about and access to the opioid overdose preventative.

ENTERTAINMENT THIS WEEK IN BR

BY CAMILLE MILLIGANJUNE

and

concert

From Los Angeles, California, hardcore punk band Terror is performing at Chelsea’s Live on Wednesday at 8 p.m.. Doors open at 7 p.m. and bands Muscle and BRAT will open for the show. Tickets are $25.

JUNE

SPORTS KNOCKED DOWN

LSU softball’s season ends with 8-0 loss to Stanford in super regionals

BY JASON WILLIS @JasonWillis4Deep into the postseason, brutality is as much a part of the game as triumph.

For every team that lives to play another day, one goes home.

On Sunday, May 26 in the decisive game three of the super regionals, each play that prompted a Stanford player to jump up and down was matched by a Tiger’s head held low.

Once again, LSU was brutally eliminated from the NCAA Tournamen, this time with a 8-0 loss, called in the sixth inning by mercy rule.

“We just didn’t get a break,” head coach Beth Torina said. “Not one break.”

Through four full innings, the match was a scoreless pitcher’s battle between Stanford sophomore ace NiJaree Canady and LSU first team All-SEC sophomore pitcher Sydney Berzon.

The pivotal sequence of the game came when LSU had finally put together its first real threat to score with the

bases loaded and only one out in the top of the fifth inning.

Junior outfielder McKenzie Redoutey stepped up to the plate and made an attempt at a sacrifice fly; however, Stanford’s throw home was fast enough to get the runner out, squashing a golden opportunity for the Tigers to break the scoreless tie.

Just three pitches later in the bottom of the same inning, a ball got behind Redoutey in right field for a triple that later became the game’s decisive first run.

From there, Stanford blew the game open with an explosive surge: eight hits and seven runs in the inning. Stanford tacked on another run in the bottom of the sixth to officially bring the game to an end.

It was a whirlwind turn of events, the kind of reversal that might give you whiplash.

At the end of it, LSU’s season was over.

“I wish I had another five years, 10 years with this group,” Torina said through tears after the game. “They’ve done everything right the

whole way.”

As the No. 8 seed in the tournament, Stanford of course presented a hefty task for LSU, due in part to Canady, the unquestionable best pitcher in the league.

Canady was the consensus national freshman of the year last year and followed up that campaign with a nation-leading 0.67 ERA and 307 strikeouts.

LSU didn’t get a break from Canady at any point of the three-game series.

The Tigers surprisingly pounced on Canady for three runs in the first inning of game one and hammered her for four more in the fifth inning on back-to-back home runs. The game would eventually end midway through that inning when LSU was awarded the 11-1 win by mercy rule.

The second game was more characteristic of Canady: a masterclass shutout to hold LSU to just two hits and three walks.

The final game of the series was more of the same, with the Tigers mustering only three hits.

Stanford relied on Canady to deliver for three straight nights, and she did.

This season and this series were pivotal turning points for LSU, a program that had unceremoniously bowed out of the NCAA Tournament in the regional round in backto-back years.

In 2022, LSU was disappointingly swept out of the postseason with two straight losses in the regional round for the first time in school history.

Last year, it hosted a regional and put itself in a position where it needed only to win one of two games against UL-Lafayette to advance to the super regionals. The Tigers lost both games and were again eliminated.

Under Torina, the Tigers have made it to the Women’s College World Series four times, but they haven’t done so since 2017. Postseason success has been relatively scarce for a program with high expectations.

This seaso, it was important for Torina to re-establish the standard the program has come to expect since her hir -

ing in 2012. In many ways, LSU answered the call.

From the jump of the season, LSU had the look of a dominant team.

The Tigers were outstanding in non-conference play, opening the season with 24 straight wins, including one over a Texas team that is now the NCAA Tournament’s top seed.

LSU peaked at as high as No. 2 in the national polls.

However, the Tigers also finished 12-12 in the SEC, winning only two series against Kentucky and Texas A&M.

Despite cooling off to finish the season, LSU did enough to earn the No. 9 seed in the NCAA Tournament and swept its way through the Baton Rouge Regional to earn a spot in the super regionals for the first time since 2021.

Still, the program is left with questions after yet another brutal postseason collapse.

With that uncertainty clouding what was a remarkable season and six members of the starting lineup graduating, LSU is at a crossroads.

Seimone Augustus to join women’s basketball coaching staff

BY JASON WILLIS @JasonWillis4LSU women’s basketball announced that it’s adding to its coaching staff with the hiring of team legend Seimone Augustus on Monday, May 20.

Augustus is one of the greatest athletes in LSU history, having been a two-time

Naismith player of the year during her time with the Tigers from 2002-06 and reaching three NCAA Tournament Final Fours.

For her contributions to LSU women’s basketball, being the key figure in what was the team’s most accomplished period before their recent run, Augustus had her No. 33 jer -

sey retired by LSU and a statue erected in front of the school’s basketball practice facilities.

After her LSU career, Augustus then went on to become one of the most storied players in WNBA history, finishing her career as an eight-time all-star and four-time league champion with the Minnesota Lynx.

Now, Augustus will return

home to her native Baton Rouge on the bench with head coach Kim Mulkey. Augustus most recently held an assistant coach position with the Los Angeles Sparks in 2022. Augustus will fill the hole in the coaching staff left by the retirement of coach Johnny Derrick, who had been a consistent member of Mulkey’s

staff dating back to 2000. She’ll add another knowledgeable voice to the Tigers, who are looking to return to national championship contention after a season that ended in the Elite Eight. With key players such as Angel Reese and Hailey Van

departing from the team, experience like Augustus’ will be valuable.

OPINION

End of an era: the last of library graffiti before renovations

ISABELLA’S INSIGHTS

ISABELLA ALBERTINI

@BasedIsabella

The library is a place to study and prepare for finals and exams. But a lot of people miss the fact that it’s also an art gallery offering a vast collection of graffiti art created by distressed students throughout the years. Ironically, these students turned to comedic designs to vent their anxious academic feelings. In no particular order, here are ten pieces of graffiti that stood out to me:

All photos by Isabella Albertini

“Finals are killing me.” Two things we despise: finals and Bama. Whoever drew this elephant must’ve been suffering from very bad studying anxiety because it’s almost sacrilegious to draw that animal in Tiger country.

“There is nothing new under the sun.” A philosophical phrase. Truly, this is nothing new. Students have been doing graffiti on desks for as long as students and desks have coexisted. The stubborn refusal to study, to do what’s best for us in the long run instead of ceding to temptation and laziness in the short run, is as much of a rite of passage in college life as it is to write down your initials or the date on an old and beaten plank of wood in the library. This concludes our tour of graffiti art.

EDITORIAL BOARD

Colin Falcon

in

“Microwave picture.” There’s a lot going on with this artwork. First, we’ve got a robotlooking head looking straight into a microwave, and written above the question “what’s the wifi password?” There’s the date August 8, 2022, in red and a phrase that says “dolphin noises” in the upper left. Just chaos.

“Beyoncé was here.” There’s just no way. Someone fact-check this right now. This can’t be true. Because if it is, someone take this desk to the LSU Museum of Art right now to preserve the desk where Queen B once studied.

The Reveille (USPS 145-800) is written, edited and produced solely by students of Louisiana State University. The Reveille is an independent entity of the Office of Student Media within the Manship School of Mass Communication. Signed opinions are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the editor, The Reveille or the university. Letters submitted for publication should be sent via e-mail to editor@lsu.edu or delivered to B-39 Hodges Hall. They must be 400 words or less. Letters must provide a contact phone number for verification purposes, which will not be printed. The Reveille reserves the right to edit letters and guest columns for space consideration while preserving the original intent. The Reveille also reserves the right to reject any letter without notification of the author. Writers must include their full names and phone numbers. The Reveille’s editor in chief, hired every semester by the LSU Student Media Board, has final authority on all editorial decisions.

“Keep Working. -No.” We’ve all been there—that little voice that tells us to do one more math problem or write one more sentence. But no. We’ve had enough already.

However unfortunate it may seem, this magnificent collection of scholastic angst will not be on display forever. The LSU Library is set to be remodeled soon, and these works of art will likely be lost to history. So next time you’re studying for your bio-chem final or working on your senior thesis, take a moment, pause and contemplate the graffiti art that surrounds you in the LSU Library.

Isabella Albertini is a 24-yearold mass communication junior from Lima, Peru.

“Equality for everyone. That’s most important.”