U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service

Summer 2013

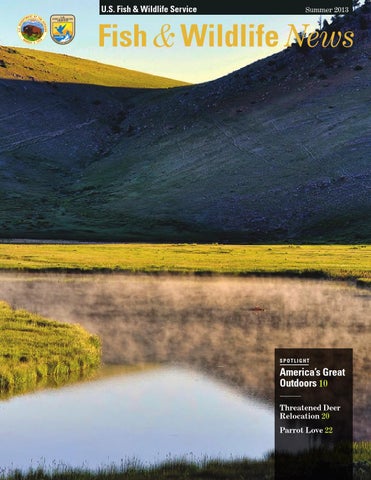

Fish & Wildlife News

spotlight

America’s Great Outdoors 10 Threatened Deer Relocation 20 Parrot Love 22

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service

Summer 2013

Fish & Wildlife News

spotlight

America’s Great Outdoors 10 Threatened Deer Relocation 20 Parrot Love 22