5 minute read

Ananth Udupa

Ananth Udupa

Exhibitions on Erasure

2345. The river is my sister-I am its daughter. It is my hands when I drink from it, My own eye when I am weeping And my desire when I ache like a yucca bell In the night. The riversays, Open your mouth to me, And I will make you more.

Because even a river can be lonely, Even a river will die of thirst.

I am both-the river and its vessel. It maps me alluvium. A net of moon-colored fish. I’ve flashed through it like copper wire.

A cottonwood root swelling with drink, I tremble every leaf in libe, every bean to gold, Jingle the willow in the same song the river sings.

I am it and its mud I am the body kneeling at the river’s edge Letting it drink from me.

Natalie Diaz, exhibitions from the American Water Museum

-Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities

Natalie Diaz’s postcolonial love poem, “exhibitions from the American Water Museum”1 discusses the erasure of the Native identity by systemic mechanisms of colonial and post-colonial definition, meaning, the death of the physical body in colonial onquest but also the infatuation with the Native artifact and metaphorical death in contemporaneity. Creating different visual motifs, the reader follows Diaz with descriptions of various “exhibits,” detailing how the Native person interacts with the various frozen artifacts of their own culture and social practices of entering a museum space. These interactions and collisions between erasing forces and “erased” objects will be analyzed in closer detail and implemented into the design of an urban residential architecture project in the city of Phoenix.

Diaz works to understand this complex set of relations by walking the reader through a space and populating the stanzas with what the urban Native sees. As the title of the poem insinuates, the poem largely describes the relationship between the Native experience and water, first to describe the origin - “green energy” - and later to detail the lack of autonomy - “tengo sed”2. These images are interwoven throughout this metaphorical walk through the museum, alongside motifs and dioramas of stories rejected by the media like the Flint Water Crisis.

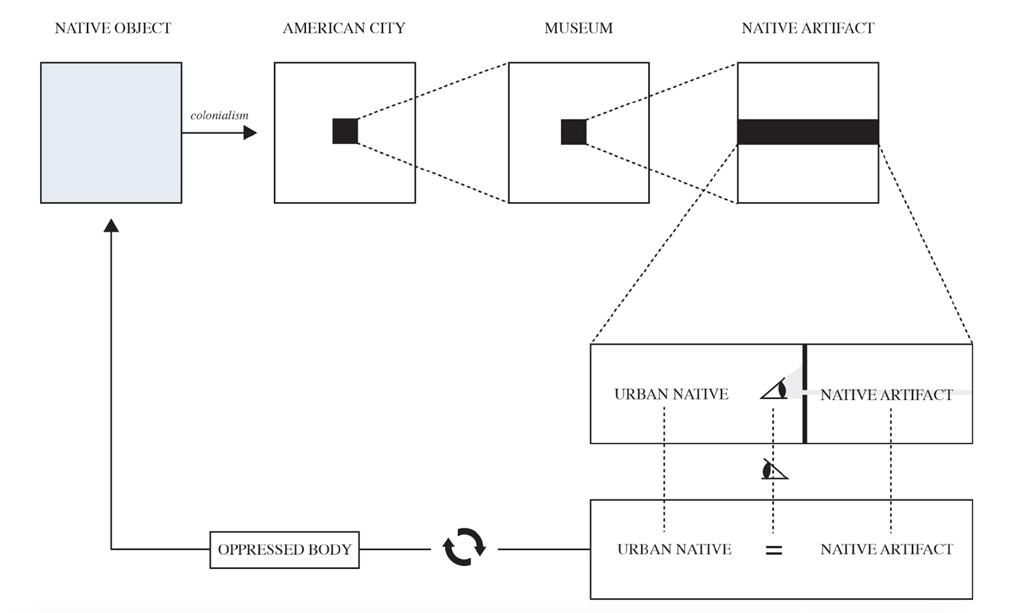

The close reading of the excerpt illustrates the erasure and power in defining the Native object as a museum artifact. Walter Benjamin toyed with the ideas of reproducibility, which follow a parallel vein to the content of this poetry, specifically in understanding the “aura” or original purpose of the work of art. In his text, “The work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”3, He posits that the “unique value of the ‘authentic’ work of art has its basis in ritual, the location of its original use value” 4. In this, the Native object originated its autonomy and authenticity in its ritual. As he defines the pivotal factor to be authenticity, the Native object is “jeopardized when the historical testimony is affected is the authority of the object,” which is what occurred through the conquest and continued inhuman treatment of the Native peoples by the “American Museum” 5 .

The place of the artifact in a museum takes an object created for cultural authority and identity and places it into a museum, reinventing it as a work of art made for reproduction through the context of technology and media. What is important to extract from this close reading is that Diaz introduces a deconstructive lens, showing the never fulfilled desire of erasure and control by the American city. The urban Native is forever the oppressed, in a cycle with the American city desiring erasure. There are also parallel cycles of oppression alongside the Native, but the Native is found at the bottom each time, erased and forgotten, to where “We’ve been crying out the past 600 years --”6. Benjamin labels the movement from defining the original work of art to a work of reproduction as a shift from ritual to politics. The artifact or work of art describes a certain

1 Natalie Diaz, “exhibitions of the American Water Museum,” Postcolonial Love Poems. (Minnessota: Graywolf Press, 2020) 2 Ibid., 63, 65 3 Walter Benjamin. “The work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” (Finland: Aalto University, 1935) 4 Ibid., 220 5 Ibid,. 218, Diaz 67 6 Natalie Diaz. “Exhibitions”. 65 7 Burt Barraza. “ 101 Highway construction.” AZCentral. 8 Natalie Diaz. “Exhibitions”. 64 9 Ibid., 10 AZDot. “Phoenix Freeway Park” 2010 motif - magics, service, community. But, the ideas of reproduction emerge as products of capitalism and politics, which will be explored further in the next section.

Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, many urban “meccas” in the US began to develop expansive highway systems which would cut down the travel distance to get from point A to point B, and also allow for suburbanization. The city of Phoenix was no different, with the expansion of the Interstate 10 and the Route 51. Resultantly, many ethnic communities were displaced in order to create a more expansive urban city. Multiple middle class LatinX and African American communities, including the Golden gate Barrios and Okemah community, were forced to move out starting in the second half of the 20th century)7. The erasure of these communities emulates the erasure mentioned in the ark of the urban Native detailed in Diaz’s poetry. The highway construction project “discover[ed] them with city. Crumble[ed] them with city. Erase[d] them into cities named for their bones”8. We see the definition and cleansing of the “new Native” in the 20th cent. city of Phoenix, just like that of colonial America 9 ..

The narrative ark of the erasure is silence. The city rejected the cries of the minority but accepted that of the majority. During the reconstruction of the highways, one plot of the 1-10 was to run through a white, suburban residential community. But, because of their protests to their culture and heritage, the Papago Freeway Tunnel Park was created; the highway was constructed to go underground and have a park on the top level. The tunnel “represented a successful culmination of a state, city, and federal partnership forged by the challenge of a concerned public,” according to 1990 Federal Highway Administrator, Thomas Willet10. The voice of the majority, the oppressing was heard so loudly, it became a stamp of pride. But, the many ethnic peoples, who had to evacuate and were not even given the opportunity to speak for their land and heritage. Inspired by Diaz’s poetry describing the interaction of the two opposing yet cyclical forces, what would the collision of the erased and erasing look like? Figure 3 is a simple montage with the theoretical inspirations for a low-rise residential project and the site plan, showing the road intersections, 8th Ave and N Roosevelt St. (nearly five miles south of the Papago Freeway Tunnel Park), and basic roof plan for the building.