‘THE GOLDEN AGE’

WITH DR KENT WEEKS TWINTHREECABINS AVAILABLE

CAIRO TO ASWAN - THE JOURNEY SOUTH

DEPARTING 1st MAY 2020

This spectacular cruise is accompanied throughout by Kent Weeks, one of the most celebrated archaeologists in the world. Known for his work on the Theban Mapping Project and his re-discovery of KV5, the largest tomb ever found in the Kings’ Valley.

Our privately chartered 5-star deluxe vessel, the SS Misr was built in 1918 and was once owned by King Farouk. She boasts exquisite public rooms and the friendliest, most efficient staff on the river. Our Luxury cruiser has just 24 cabins, including 8 suites, offering the very highest standard of comfort, service, cuisine and hygiene.

Join us on this wonderful cruise leaving Cairo on 1st May, ending two weeks later in the lovely southern city of Aswan. We travel in true AWT style. There are no galabeya parties; there is no musak; there are no quizzes; only AWT like-minded passengers enjoying the serene beauty of the River Nile. This fourteen night cruise is full board throughout and this wonderful itinerary sailing the length of the Nile will be remembered for years to come.

On our journey we will visit some of the most important sites of Ancient Egypt. We begin with the Pyramids at Giza and the mighty Sphinx and the more remote Meidum Pyramid, then continue in to Middle Egypt where we will explore the tombs of Beni Hassan, Tuna el Gebel and Ashmunein.

A full day at Amarna, the capital city of Pharaoh Akhenaten and Queen Nefertiti, including entry to the Royal Tomb.

At Abydos we can view some of the finest reliefs in Egypt within the Temple of Seti I, and at Dendera we see the beautiful astronomical ceilings recently restored to their original glory. On to Ancient Thebes with in depth visits to the major sites in Luxor, including the Valley of the King’s, before sailing to the Ptolemaic Temple at Kom Ombo. In Aswan we make visits to the Temple of Isis at Philae, the huge Unfinished Obelisk and the Nubia Museum.

All the while sailing along the River Nile relaxing in style on our luxury cruiser. Time for birdwatching, reading, taking in a lecture or two and generally just having a wonderful time.

STANDARD TOUR PRICE: £5 ,450

(per person based on sharing a twin or double cabin)

Cabin upgrades are available: Standard Suites & Upper Deck.

CALL NOW TO BOOK: 0333 335 9494 OR GO TO www.ancient.co.uk

ancient world tours

EGYPTIAN ARCHAEOLOGY

No. 55 Autumn 2019

www.ees.ac.uk

Editor Jan GeisbuschEditorial Advisers

Aidan Dodson

John J Johnston

Caitlin McCall

Luigi Prada

Advertising sales

Phone: +44 (0)20 7242 1880

E-mail: jan.geisbusch@ees.ac.uk

Distribution

Phone: +44 (0)20 7242 1880

E-mail: contact@ees.ac.uk

Website: www.ees.ac.uk

Published twice a year by the Egypt Exploration Society

3 Doughty Mews London WC1N 2PG

United Kingdom

Registered Charity, No. 212384

A Limited Company registered in England, No. 25816

Design by Nim Design Ltd

Set in InDesign CS6 by Jan Geisbusch

Printed by Intercity Communications Ltd, 49 Mowlem Street, London E2 9HE

© The Egypt Exploration Society and the contributors. No part of this publication may be reproduced without prior permission of the publishers.

The opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the aims or concerns of the Egypt Exploration Society.

ISSN 0962 2837

Editorial

Nile Delta, central Egypt or Sudan, New Kingdom or Late Period, field archaeology or archival research –the discipline of Egyptology again presents itself as astoundingly rich and varied.

Our autumn issue again shows the breadth of work done or supported by the EES, geographically – from the Delta to the Third Nile Cataract in Sudan – but equally in terms of subject matter, ranging from fieldwork to archival, conservation and training activities. It also demonstrates the support of our members and friends: More than £25,000 in donations were given to the Society in response to a call for support of our project to rehouse the EES’ collection of glass-plate negatives. Five thousand of these fragile and irreplaceable photographic artefacts from the earliest days of the Society’s fieldwork in Egypt have now been preserved for future generations. A big and heartful ‘thank you’ for your generosity!

We are just as delighted to report on other teams’ and researchers’ work done in recent months: Carina van den Hoven for the Leiden Mission offers a fascinating account on tomb reuse in New Kingdom Thebes; Christian Leitz and Hisham el-Leithy bring the pronaos of the temple of Esna back to splendidly colourful life; Bérangère Redon delves into the history of wine-making at the Late Period / Ptolemaic town of Plinthine; Dietrich Raue and his colleagues summarise the archaeological and iconographic research done on the colossal statue of Psamtik I discovered two years ago in Heliopolis; and Paola Davoli presents an intriguing and rare artefact from the oasis site of Dimeh es-Seba – an architectural model of the Soknopaios temple, found in the very temple it represents.

Jan G eisbusch

New investigations on the Third Cataract in Sudan

Cédric Gobeil and Stephanie Boonstra

The sixth Delta Survey Workshop

Penelope Wilson

The Delta Survey: recent work in Kafr el-Sheikh and Beheira

Israel Hinojosa-Baliño, Elena Tiribilli and Penelope Wilson

Space and memory: tomb reuse in New Kingdom

Thebes

Carina van den Hoven

The ancient colours of Esna return

Hisham el-Leithy, Christian Leitz and Daniel von Recklinghausen

Digging Diary 2019

An Egyptian grand cru: wine production at Plinthine Bérangère Redon

Psamtik I in Heliopolis

Aiman Ashmawy, Simon Connor and Dietrich Raue

The contra-temple of Soknopaios and its architectural model

Paola Davoli

Rehousing the EES glass-plate negatives

Stephanie Boonstra and Alix Robinson

New investigations on the Third Cataract in Sudan

In 2018, the Egypt Exploration Society was granted a concession by the Sudanese National Corporation of Antiquities and Museums (NCAM) for an area of roughly 4 km2 along the eastern bank of the Nile’s Third Cataract. Cédric Gobeil explains the results of the topographical survey and preliminary excavation of the stone settlement within the concession, Stephanie Boonstra discusses the wider survey of the concession and the future potential for the Third Cataract region.

The Third Cataract Project

The Third Cataract Project concession is located in Lower Nubia, roughly 20 km north of Tombos. It is bordered on the west by the Nile along the rapids of Foogo (image above) and is situated south of Arduan Island. The area is also intersected by a palaeochannel of the Nile on its eastern side. Previous surveys (such as that conducted by Ali Osman and David Edwards) identified several archaeological features throughout the region, including desert walls [HBB024026], a stone settlement [HBB017], hieratic

graffiti [HBB011], and cemeteries [HBB001, SDK018].

In February 2019, the EES team conducted a surface survey of the region with a more thorough topographical survey of the stone settlement HBB017, as well as an exploratory excavation of a discrete area, discussed here.

Life on the edge – the position and role of HBB017

Previous surveys of the Third Cataract region have identified a cluster of archaeological sites between the modern villages of Habaraab and

Uraaw, but their dating and function within the wider geographical context of the region remains largely unknown. No significant Egyptian settlements of the New Kingdom are known between Nauri and Tombos, 50 km further downstream, with the exception of the stone settlement identified as HBB017 by Ali Osman and David Edwards (2011) during their survey of the area. Their investigations revealed ‘a type of site that cannot easily be paralleled elsewhere amongst New Kingdom settlements in Middle Nubia’ (2011: 87). Its position on the western side of the palaeochannel may be evidence of a role in trade routes around the rapids of the Third Cataract. This transitional zone, between Lower Nubia and the Kerma basin to the south, is already known to have held some strategic position for New Kingdom rulers as evidenced by inscriptions dated to the Thutmoside Period

focused attention primarily on HBB017 (image below centre). The objectives in this season were to create a topographic plan of the site, conduct a surface survey of material finds to indicate a broad occupation period, and to initiate a test excavation of one of the areas of the site.

HBB017 measures roughly 160 x 150 m (24,000 m2) within which are several clusters of archaeological features built on and around the uneven natural rock. No defensive surrounding wall is apparent, though a level terrace on the east side abutting the palaeochannel is clearly visible.

Individual occupational structures within the settlement are constructed from roughly cut dry stones of schist, quarried or gathered from the local area. Despite many collapses, it was possible to recognise subcircular walls separating several groups likely to be household

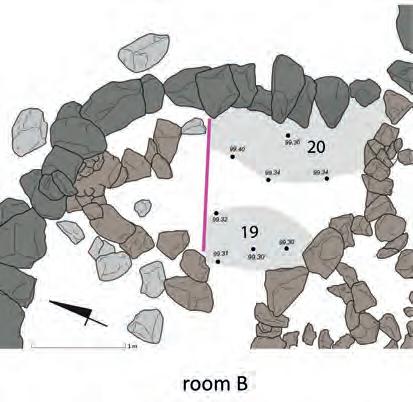

Below centre: the stone structures of the settlement HBB017.

Below: map of stone settlement HBB017 indicating the minimum number of complete ceramic vessels in each area, as well as the proportion of which were Classic Kerma/ New Kingdom in date based upon the surface survey.

at Tombos (as well as the later stela of Sety I at Nauri). A holistic investigation of the wider landscape may provide significant information regarding events in this region during the early Eighteenth Dynasty conquest of Upper Nubia. To better understand this situation as well as the perceived cultural exchange between occupying populations, the Egypt Exploration Society created the Third Cataract Project in February 2019.

Following an initial survey of the concession area with careful checks against the published survey of Osman and Edwards, the work

units surrounded by small enclosure walls or courtyards (map above). From the plan created this season, twelve units, some containing several rooms, were identified. The centre of the settlement is more densely constructed than the outlying structures, which suggests that the settlement grew outward over time, also occupying higher land.

Following the initial topographic survey, a surface survey was conducted in and around the settlement. Diagnostic surface finds, mostly ceramic sherds and evidence of stone tool manufacture, were mapped, collected, and

recorded. As expected, the survey revealed concentrations of artefacts within the occupational structures and in areas of waterflow out of the settlement.

Surface pottery revealed possible cultural exchange owing to a dominance of Classic Kerma Nubian pottery and New Kingdom Egyptian pottery. This gives further credence to the suggestion that this area played a role during the early New Kingdom reconquest of Nubia and perhaps hints at an earlier foundation for the site during the Kerma Period. Pottery dating to Roman and Christian periods of occupation were found in smaller quantities, particularly in the structures furthest from the centre of the settlement (Areas 1, 2, 4, 5 and 13), and may be evidence of later settlement phases. Findings from these initial surface observations already provide a complex picture of occupation in this borderland between Lower and Upper Nubia, particularly during the Kerma Period and early New Kingdom.

Area 3 – life on the Third Cataract

In order to affirm the archaeological potential of HBB017 and its level of preservation, it was decided to excavate a small area. Area 3, a single occupational unit was selected due to its smaller size (roughly 200 m2) and clearly defined layout (plan bottom left). The interior space is divided into five delineated rooms named A to E. Initial results obtained indicate that Area 3 was a domestic household and each room had a specific function. In order to

assess the stratigraphic levels preserved in Area 3, and by extension perhaps also the rest of the site, one half of each room was excavated. In room E the stratigraphy descended as far as 1 m, a depth that may be echoed elsewhere in HBB017.

Though unidentified at present, the entrance to Area 3 was probably into room A which, from the layout, appears to have been a courtyard fronting the household (plan centre page). Its width indicates that it was most likely not covered by a roof. Supporting this conclusion, a series of three firepits containing black ashes (contexts 18 and 31) were discovered along the south wall of the room,

which could only have worked properly in an open-air setting to allow smoke to be evacuated. Near these firepits is an L-shaped stand (context 26) constructed from smaller loose stones that seems to have been used to hold ceramic jars. This is demonstrated by two shallow holes built into the stand each with a diameter of 30 cm. However, the exact use of these features is unclear.

Room B is the smallest of the five rooms identified and is located at the end of a narrow corridor linking it to Room A. Contexts 19 and 20 here contained deposits of loose sand mixed with dark grey and white ashes (plan top of facing page). The peculiarity of this level is that it contained a high quantity of animal bones, especially fish bones. This appears to indicate that the function of this space included the storage, processing, or discarding of food and gives evidence toward the diet and food supplies of the community living here.

Many structures within the settlement had rounded walls. Room C in Area 3 is unusual in its circular shape and seems to have been constructed abutting, and therefore probably after, Room D (plan above right). The section partially excavated this year revealed only a few layers of loose sand mixed with some dark grey ashes. The low number of finds in this room may indicate that it was cleared by the occupants during abandonment or had been emptied during a later reoccupation of the site.

Room D seems to have been constructed at the same time as the whole household unit, as the main enclosure wall of Area 3 deviates to coincide with the eastern wall of the room (image p. 8, top). This room contained many contexts relating to a probable production space. For example, context 11 comprised a small firepit associated with a stone tool and possibly a quern stone, while context 12 had flat stone slabs arranged in a semicircle with

one stone tool left in the middle. In connection with both contexts 11 and 12, context 29 was defined by a set of three stone tools (round pounders/grinders) left close together (image p. 8, centre). This evidence may suggest work related to food production.

Room E may have been built as a later extension to the household, as it is located outside of the main perimeter of the unit and abuts its west side (plan p. 8, bottom). Its rectangular shape is markedly different from the other rooms of the household, which are more circular. Beneath a layer of collapsed building stones (context 3), an event that presumably occurred sometime after the

abandonment of the room, was a level of collapsed mud bricks (context 9). It is possible that these mud bricks are the remains of either part of the roof of this room or part of a structure standing either in the room or on top of the lower courses of building stone. At this time, it is not clear which of these potential scenarios is correct. Context 9 covered a thick horizontal layer of soft sand mixed with ashes that contained a significant quantity of animal bones and small bivalve shells (context 22). It is probable that this room was used as a storeroom or even as an animal pen, particularly as it has no adjoining doorway into the main structure of the household unit.

The promising results of this survey and test excavation demonstrate the potential of this site for future investigations on the purpose and use of this unique settlement and its surrounding region.

Future potential for the Third Cataract region

After an exciting season, the EES team was able to gain a greater understanding of the potential of the Third Cataract region for research.

As well as the findings at HBB017 outlined above, the team were able to identify several features worthy of further investigation in the region. Many were known from previous surveys, notably that by Osman and Edwards (2011), but several others including cemeteries containing hundreds of graves (HBB031-032), rock art, and possible production areas (HBB029) can now be added. By working together with the local community of Uraaw, the team were able to gain a better understanding of the geography of the concession and to find these further areas of interest.

A further survey utilising hand-held GPS to conduct a systematic examination of the region will allow the proper recording of each feature now known. The survey will allow the identification of areas that can be outlined for discrete research projects allowing multiple experts (ceramicists, palaeographers, geoarchaeologists, osteologists, etc.) to contribute towards greater understanding of this transitional zone of intercultural communication between Lower and Upper Nubia.

Further Reading:

A. Osman and D. Edwards, The Archaeology of a Nubian Frontier. Survey on the Nile Third Cataract, Sudan (Khartoum, 2011).

• Cédric Gobeil was Director of the EES at the time of the Third Cataract Project. He is now a curator at the Museo Egizio in Turin and adjunct professor at the Université du Québec à Montréal. Stephanie Boonstra is the Collections Manager of the Egypt Exploration Society and the Managing Editor of the Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. She was a team member of the Third Cataract Project in 2019 and has previously worked on EES concessions in the Nile Delta of Egypt.

The sixth Delta Survey Workshop

The Delta Survey, initiated by the EES in the 1990s, aims to document the hundreds of archaeological sites in the Nile Delta and to encourage further research on them. Since 2009, the Delta Survey Workshop has offered a bi-annual opportunity to catch up on the latest work done in the region. Penelope Wilson reports on its sixth instalment.

The sixth Delta Survey Workshop (DSW) took place in Mansoura from 11 to 13 April 2019, sponsored by the University of Mansoura along with the British Academy / Egypt Exploration Society and in cooperation with the Ministry of Antiquities (MoA). Over three days, 22 papers and five posters provided updates on established and new archaeological work in the Nile Delta. Key papers were given by Prof So Hasegawa on Kom el-Debaa, Dr Cristina Mondin on Kom el-Ahmar, Dr Ayman Ashmawy on Kufur Nigm and Dr Sayed Abd el-Halim on Tell Hebua. Further reports came from Dr Slawomir Rzepka and Lukasz Jarmusz on Tell Retaba, Dr Anna Wodszinka on the Wadi Tumilat and Prof Jay Silverstien and Stacey Baghdi on Tell Timai.

In addition, there were reports on new work at Tell Tibilla by Mansoura University, at Sais, Buto and Quesna by the Ministry of Antiquities, and Delta Survey projects in Kafr el-Dawar. Other papers explained the importance of tannur-ovens, discussed retrogressive analysis of photographic archives for gaining a understanding of the site of Naukratis, and addressed the gathering of information on private collections in Alexandria. Tea / coffee breaks and the evening meals gave opportunity for attendees to meet colleagues, make new contacts and catch up on the progress of projects in the north of Egypt.

Map data ©2019 Mapa GISrael, ORION-

Mansoura was an ideal and welcoming host for the workshop, with the lectures attended by many of the local students as well as archaeologists from all over the Delta. On the final day of the workshop, a number of delegates and MoA colleagues made a trip to Tanis (Sa el-Hagar) to visit the site and the newly opened royal tombs. We are grateful to the authorities at the University of Mansoura and in particular Prof Maha el-Seguini and Dr Ayman Wahby for

their help in organising the workshop. As always, Essam Nagy in the EES Cairo office was very proactive in making the event a success, and we are grateful for the support of Prof Khaled elEnany, Dr Hisham el-Leithy and Dr Nadia Khedr of the Ministry of Antiquities. We are now working on the publication of papers from DSW 5 in Alexandria and DSW 6 in Mansoura.

The Delta Survey: recent work in Kafr el-Sheikh and Beheira

In spring and autumn 2018, the EES Delta Survey, in collaboration with Durham University, investigated 14 little-known selected sites of the central and western Delta belonging to Kafr el-Sheikh and Beheira governorates. Israel Hinojosa-Baliño, Elena Tiribilli and Penelope Wilson describe the main results of the most recent EES fieldwork which aimed to reconstruct the history and the ancient environment of remote sites around Lakes Mareotis and Burullus.

Delta waterways and landscapes

The Delta landscape has changed considerably since ancient times. As shown in the reconstructed map there were significant bodies of water such as the Lakes Mareotis and Edku in the western Delta as well as swampy border areas of Lake Burullus in the north. The lakes were fed by waterways and tributaries, which offered excellent lines of communication through the field basins, swamps and complex networks of water systems. Settlements were sustained by agricultural land and proximity to the waterway system, and it is these networks from the Ptolemaic to Late Antique Periods (300 BC to AD 700) that the project aims to investigate by collecting information from the chosen sites (see maps p. 13).

In 2018, two survey missions led by Penelope Wilson and Elena Tiribilli were carried out in ten selected sites of Kafr el-Sheikh governorate and four sites in Kafr el-Dawar province of Beheira governorate. The information concerning the dating and archaeological material found at the sites was added to the Delta Survey project database, a special project funded by the British Academy and administered by the EES. As little information was known about the sites selected for survey, the objectives of the missions were to collect topographic and photographic information, to record surface pottery and material and, where possible, to carry out geophysical investigation of sub-surface

features using a fluxgate gradiometer (Bartington Grad601). The overall objectives of the work are to monitor the current preservation of the sites as well as to interpret the ancient landscape and environment of the Delta regions and make the information about the sites available through the online database of the Egypt Exploration Society’s Delta Survey for research and future archaeological excavations (www.ees.ac.uk/ delta-survey).

Lake Mareotis area

Sites in Beheira province relate both to the ancient Lake Mareotis as well as the Alexandrian hinterland, supplying the Ptolemaic-Roman capital city with food and access to the wider resource base of the Delta and Nile Valley. Kom el-Ghasuli was part of a much larger group of settlements or one large settlement in antiquity. The remaining site presents an irregular shape, characterised today by two sandy mounds of which the highest is 2.14 m above the field level. The northern area of the kom has been levelled to two flat areas (image above). There is no archaeological material visible on the surface, but sections at the side of the kom show clear stratified sequences of layers, including brick and pottery deposits. The surface pottery indicates an occupation range from the 2nd century BC to the 7th century AD, and there was a high presence of imported amphorae and table wares from Cyprus, the Levant, and

Asia Minor. Similarly, Kom Abdu Pasha has been levelled for the reclamation of agricultural land over time and nowadays only a small part of the tell is preserved, surrounded by irrigation ditches and fields and partially overbuilt by the modern village of Ezbet Abdu Pasha (image right). The surface pottery shows a high percentage of material of local production, such as Egyptian amphorae and vessel stands, dated mainly to the Early and Late Ptolemaic Period. It, too, was probably part of the supply chain between the lake and the Canopic Nile branch.

Kom el-Magayir I, II and III were originally part of one settlement but are nowadays separated by a modern road and the Shereishra canal, partially overbuilt by the modern villages of Baba el-Koupra and elHilbawi and by a modern cemetery. The sites may have lain along a waterway extending into the ancient lake, as their linear arrangement suggests. The surface pottery collected mainly consists of Egyptian table wares, local and imported amphorae coming from the eastern Mediterranean. It suggests a long period of human activity, from the 3rd century BC until the 7th century AD.

Tell el-Mahar is surrounded by fields and irrigation ditches, and its eastern part has a modern cemetery that is gradually extending towards the west side, on the top of the mound. The name of the site means ‘mound of shells’, derived from the fact that the surface of the site is covered in many shells. They may have come from the nearby Lake Mareotis in antiquity, when mud from the lake was used to make bricks. As the bricks decayed they released the shells that now lie on the surface. Pottery from previous surveys indicates that the site was a Ptolemaic foundation, and that it was abandoned around the time of the Arab invasion in the 7th century AD. A geophysical survey has been proven to be particularly effective in reconstructing the settlement layout of this site. Indeed, the magnetic map showed that there were clear structures with rectangular plans and of different sizes on the eastern side of the flat area and on the top of the mound (image right, bottom).

Above centre: Kom Abdu Pasha. Topographic map of Abdu Pasha

Lake Burullus area

In Kafr el-Sheikh province, the area is dominated by Lake Burullus to the north, the silted-up Sebennytic branch of the Nile to the east, and many lost waterways to the west as far as the Rosetta Nile branch. Many settlements attest to the vitality of the area in the Roman and Late Roman periods in particular (1st-7th century AD).

Kom Garad lies on the western side of a bend in an ancient river channel that linked Kom el-Khawalid to the south with the double site of Kom Nashawein on the edge of Lake Burullus. Satellite imagery indicated that Kom Garad had a gridded settlement plan on the northeastern side of the existing mound (image right). Pottery on the surface was mostly of Late Roman date (4th-7th century AD), and other archaeological material including metal fragments and glass also confirmed this date. Due to the presence of a great amount of fired brick and pottery the magnetic survey was not so useful in identifying the settlement area, but did confirm that to the south-east there was most likely a water channel contemporary with the settlement.

Two sites were surveyed along the edge of Lake Burullus: Kom Dishimi and Kom Eid el-Ghash, now mostly surrounded by fish farms and only accessible by boat or narrow dykes. Both sites have a flat surface and pottery dating mostly to the Late Roman period, although Kom Eid el-Ghash is relatively high at 6 m above the level of the surrounding water and with steep sides. The geophysical survey was hindered by the great amount of brick and pottery lying on the site, but in the case of Kom Dishimi the magnetic map shows the presence of a south-north waterway through the site with structures oriented along/facing it. To the north, Mastarouah on the coast was also bisected by a channel which eventually reached the sea, indicating that perhaps it had been a port on the sea-shore. The Late Roman part of the site was located to the east, while a medieval set of structures lay to the west, dated according to the fine glazed wares and imitation Chinese celadon pottery fragments (image right, bottom). According to historical sources the port of Nastaraouh was sacked by Crusaders and abandoned in 1415. Tell Daba-Shaba, Kom Quleia and Kom Sheikh Ibrahim may all have been important settlements along a waterway to the south, feeding goods and produce through the lake to the north coast. The pottery from the sites shows that the area was flourishing in the Late Roman-Coptic period. Kom el-Qassabi perhaps lies on another set of waterways but the site was covered by a modern cemetery and further drill augering may help to throw light on the nature of this ancient mound in the future.

Tell Daba-Tida is a large ancient site with a strategic central position in the north Delta. The north part of the site has been dug away and there were a few limestone blocks in this area, perhaps suggesting that a large structure such as a temple building may once have stood here. There were substantial settlement areas to the west and east of a central low-lying pathway running north-south from the ‘temple’ area. To the north-west the cleared football field yielded excellent magnetic results showing structures with a gridded pattern in this area. The earliest pottery at the site is from the Ptolemaic period, but further work could be fruitful here.

The brief descriptions of the sites shows that each individual site has its own characteristics but can be woven into the narrative of the vibrant settlement and waterway history of the Ptolemaic to Islamic periods in the Egyptian Delta.

• Penelope Wilson is Associate Professor in Egyptian Archaeology at Durham University, Director of the EES Delta Survey Project. Elena Tiribilli is a postdoctoral Marie Curie Fellow in Egyptology at Durham University and field director of the EES/Durham University survey to Kafr el-Dawar province. Israel Hinojosa-Baliño is a doctoral candidate at Durham University and mapmaker, sponsored by Conacyt. The seasons were funded by the British Academy through the Egypt Exploration Society and through Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions (project no. 744977). The authors would like to thank Dr Khaled al-Enany (Minister of Antiquities), Dr Mustafa Waziri (Secretary General of the SCA) and Dr Nashwa Gaber (Director of Foreign Missions). Thanks are due to Directors Khaled Farhat in Damanhur and Gamal Selim in Kafr el-Sheikh for their assistance and help, as well as Essam Nagy in Cairo. We are also grateful to our teams: Rabea Reimann, Mahmoud Ali Arab, Reda Said Ibrahim Ali, Yahya el-Shahat Mahmoud, Walid Abd el-Bary Attia Zalat.

Space and memory: tomb reuse in New Kingdom Thebes

In November 2017, Carina van den Hoven launched a new fieldwork project in Theban Tomb 45, a beautifully decorated tomb dating back to the Eighteenth Dynasty around 1400 BC. It serves as a case study for the practice of tomb reuse, interpreted through the theoretical concepts of ‘space’ and ‘memory’.

TT 45 and its surroundings

Theban Tomb 45 is situated in the Theban necropolis, on the west bank of the Nile, opposite modern Luxor. The Theban necropolis is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and constitutes one of the largest ancient burial sites in the Near East. It comprises numerous monuments, including the famous royal tombs of the Valley of the Kings and the Valley of the Queens, but also more than 400 private elite tombs, as well as memorial temples and remains of royal palaces and domestic

communities. Theban Tomb (TT) 45 is situated in the area of Sheikh Abd el-Qurna, which has a large concentration of private elite tombs, most of which date to the Eighteenth Dynasty (c. 1539–1292 BC). TT 45 is situated close to the Ramesseum and the well-known tombs of Ramose (TT 55), Userhat (TT 56) and Khaemhat (TT 57) which are open to the public (image opposite page).

The plan of TT 45 shows a classical inverted T-shape. It has been quarried along a southnorth axis, with the arms of the T being roughly

in line with the east-west course of the sun. Only the transverse hall has been decorated. The longitudinal hall was quarried, but remained undecorated. The eastern side of the longitudinal hall features two openings that were closed off in modern times and may lead to other tombs. At the end of the longitudinal hall a further room has been cut to the left, leading to a sloping passage (image next page, top). After Robert Mond discovered the tomb in 1903–04, the tomb was not further explored archaeologically. The original layout of the courtyard is unknown as it is partially covered by modern retaining walls. In his excavation report, Mond mentions a shaft in the forecourt, the location of which is unknown at present. The shaft in the transverse hall is not documented in any of the old ground plans of

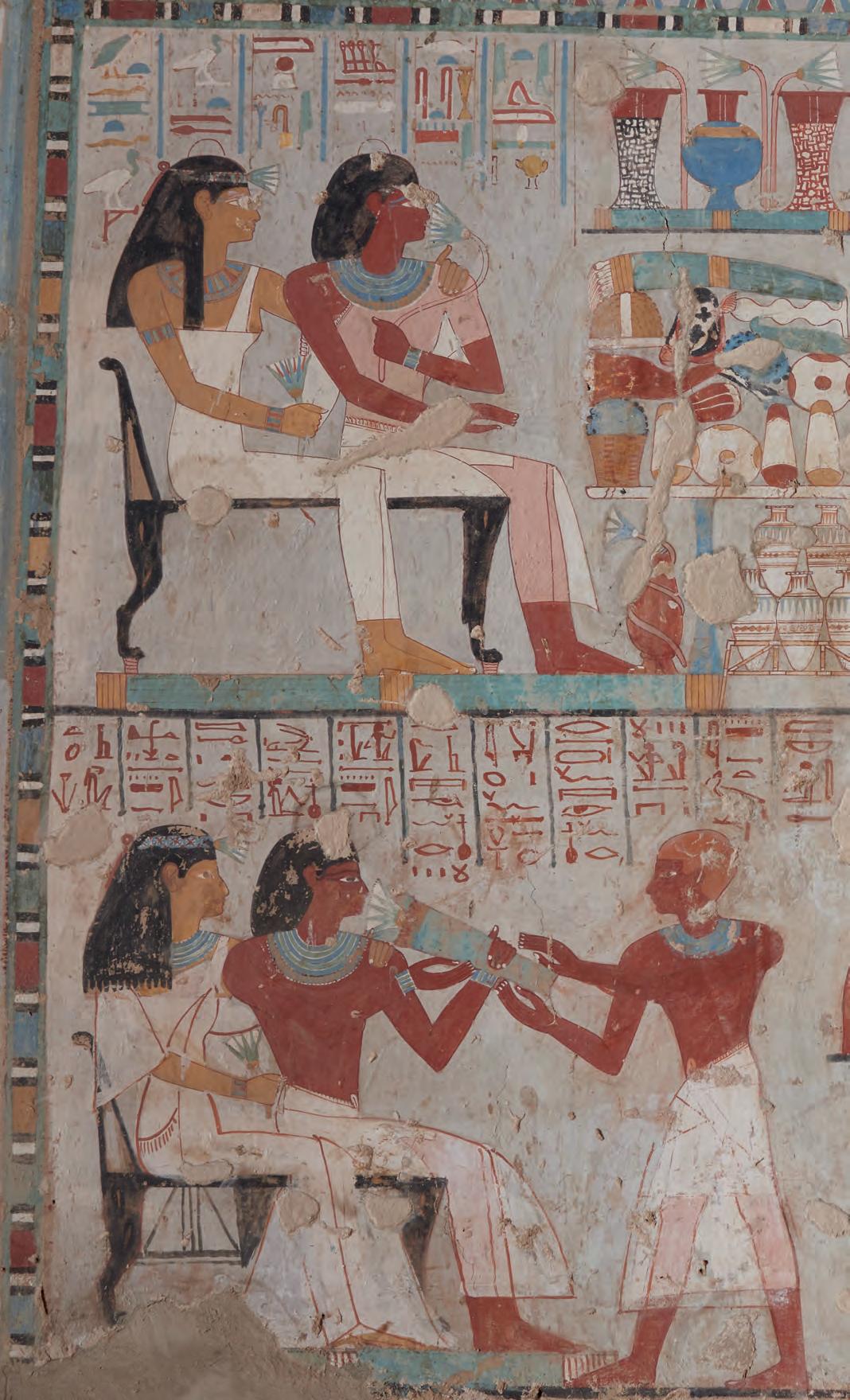

scenes and texts during the reign of Amenhotep II (c. 1425–1400 BC) for a man named Djehuty and his family. He was overseer of the household of Mery, the high priest of Amun (and owner of TT 95), as well as of the weaving workshop attached to the temple of Karnak. Djehuty is depicted in the tomb with an unnamed woman, probably his wife, as well as with his mother, also named Djehuty (image next page, bottom). Several hundred years later, during the Ramesside period (c. 1292–1069 BC), the tomb was reused by a man called Djehutyemheb. Like his predecessor, he was overseer of the weaving workshop at Karnak. His family members are also depicted in the tomb: his father Wennefer, overseer of the weavers of the temple of Amun, his mother Isis, songstress of Amun, his wife Bakkhonsu,

the tomb and seems to have been unexplored so far. One of the aims of the TT 45 Project is to carry out for the first time a full archaeological study of the tomb to enhance our understanding of its usage history, from its original construction in the Eighteenth Dynasty until today, and its position within the larger mortuary landscape of the Theban necropolis.

The two owners of TT 45 TT 45 is a fascinating case study of tomb reuse. It was built and decorated with painted

also a songstress of Amun, and their children and grandchildren (image p. 17).

Even though the practice of tomb reuse may call to mind images of usurpation, tomb robbery and destruction, TT 45 was reused in a non-destructive manner and with consideration for the memory of the original owner. Instead of vandalising and whitewashing its walls in order to replace the original decoration with his own, Djehutyemheb left most of the existing decoration in its original state. He added his own only to wall sections

that had been left undecorated by Djehuty, and he retouched a number of the original paintings. For example, the garments, wigs and furniture depicted were altered to conform to contemporary style and taste. The image on p. 18 shows an example of the numerous repaintings that were carried out in TT 45 in the Ramesside period. The upper scene depicts the first tomb owner with his mother. He is dressed in a white garment with fringed edges and a plain kilt. His mother wears a simple tight dress. These paintings were left untouched in the Ramesside period. The lower scene also belongs to Djehuty’s original programme of

decoration, but here we clearly see a number of changes made at a later date: the Ramesside tomb owner added a text in red cursive hieroglyphs, transforming the original Eighteenth Dynasty painting into a scene presenting himself as the son who offers a bouquet to his parents, Wennefer and Isis. Furthermore, the furniture, garments and the lady’s wig were retouched in order to update them to Ramesside style. The garments of all three figures have been widened and lengthened, struts and bars were added to the furniture.

The Leiden Mission: document and preserve

The first three fieldwork seasons of the Leiden University Mission to the Theban necropolis took place under the direction of the author in March and November 2018 and February-March 2019. The international team is undertaking a wide range of activities, from conservation and documentation to publication, archaeological study, art historical analysis, heritage preservation and site management. The project also provides opportunities for the further training of Egyptian staff in conservation, site documentation and archaeological research. Site management activities are carried out in close cooperation with the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities with a view to make the tomb publicly accessible. A full conservation programme aims to preserve the painted decorations for future

generations. The team is also undertaking research in preventive conservation, especially in regard to protection from flash flooding.

The entire decorative programme of TT 45 is recorded as precisely as possible, using the most recent tools and developments in the field of digital humanities, such as photogrammetry, 3D-technology, as well as digital epigraphy, reconstruction and imaging technology (image p. 19). In this way, we aim to contribute to the development and application of non-invasive digital technologies to Egyptological site documentation and publication. The art historical and material analysis of the wall paintings is carried out with the help of ultraviolet and infrared photography as well as with the software application DStretch. These technologies can enhance the traces of poorlypreserved pigments, thus improving the legibility of wall paintings that have faded over time, and detect repaintings – such as those done by the second tomb owner – that would not be identifiable with the naked eye.

Theorising tomb reuse

The double occupation of TT 45 and the way in which its second occupant dealt with its original decoration make it an excellent starting point for a research project on the mechanisms and motives behind tomb reuse in New Kingdom Egypt, which is carried out by the author at the Netherlands Institute for the Near East, Leiden University.

Tomb reuse was a widespread mortuary practice in ancient Egypt. Consequently, much information is available in terms of archaeological data. However, there is a surprising lack of academic research on this topic. Traditionally, studies of burial monuments have mainly been concerned with their original construction and decoration, and with their original owner(s). The continued use and reuse of tombs has long been of marginal interest to researchers. This is indeed surprising, because the continued use of monuments clearly forms part of their ‘life history’. Another problem in the study of tomb reuse is that the phenomenon is generally

documented only as part of the life histories of individual tombs, i.e. detached from its wider historical, cultural, and geographic context. This research project takes a new approach and explores tomb reuse in terms of the theoretical concepts of ‘space’ and ‘memory’. Its underlying premise is that the ancient Egyptian necropolis should not be considered merely as a random collection of individual tombs, but as a dynamic, internally coherent landscape. This landscape was shaped physically by the existing monuments and processional routes, and cognitively by the mortuary and commemorative practices that took place in it. Conversely, the landscape also structured mortuary practices, such as tomb reuse. Exploring tomb reuse from this perspective will enable us to go beyond the investigation of apparent motives associated with individual cases and to present an innovative understanding of the collective way in which the ancient Egyptians used and interacted with the landscape and its monuments in order to connect with their own past and ancestors. This new approach offers an opportunity for cross-cultural comparisons of the ways in which societies view the dead and their own past, an important aspect of the wider phenomenon of cultural identity still relevant today.

• Carina van den Hoven is Research Fellow at the Netherlands Institute for the Near East, Leiden University, and Collaborateur Scientifique of the Research Unit UMR 8546 AOrOc ‘Archéologie et philologie d’Orient et d’Occident’ at the École Pratique des Hautes Études (EPHE/PSL), École Normale Supérieure (ENS), and Centre National de Recherche Scientifique (CNRS). Since 2017, she has been Director of the Leiden University Mission to the Theban Necropolis. More information on the TT 45 Project at www.StichtingAEL.nl. Donations to the Luxor Archaeological Heritage Foundation to support the project and help preserve Egypt’s heritage can also be made through the website. The fieldwork project would not be possible without the generous financial support of the Gerda Henkel Stiftung (www. gerda-henkel-stiftung.de) and academic, administrative, and logistic support by the Netherlands-Flemish Institute in Cairo and the Netherlands Institute for the Near East at Leiden University. A proof of concept study on the digital documentation of the tomb paintings is funded by the Leiden University Centre for Digital Humanities. We closely cooperate with the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities and the Luxor Inspectorate of Antiquities. We thank all the members of the Ministry of Antiquities, the Permanent Committee and of the Luxor Inspectorate for permissions, advice and assistance.

The ancient colours of Esna return

The temple itself vanished in medieval times, but its surviving pronaos is still a beautiful and much-visited specimen of late Egyptian architecture. Hisham el-Leithy, Christian Leitz, and Daniel von Recklinghausen report on recent conservation work done at the structure that has revealed decorations hitherto invisible.

The pronaos of Esna, one of the last examples of ancient Egyptian temple architecture, was decorated mainly during the Roman period (1st to 3rd century AD). It is, in fact, only the front part of the original temple complex, which – unlike the (Ptolemaic) temple proper – survived because it was used as storage facility for cotton during the nineteenth century (image below). The extant walls and columns are famous for their complex hieroglyphs as well as for the topics of the scenes and iconography. Serge Sauneron published the texts of the Esna temple between 1963 and 1975 (with the final volume realised posthumously only in 2009).

In 2018, the University of Tübingen, in co-operation with the Egyptian Ministry of

Antiquities (MoA), launched a project to document the temple decoration. Its main objectives are twofold: first, it aims to continue the cleaning and conservation work started by the Department of Conservation (MoA) under the auspices of Gharib Sonbol some years ago. At the moment, this work focuses on the inscriptions and images of the ceiling, the columns as well as the upper registers of the lateral wall of the northern section of the temple. These activities are carried out by a team of Egyptian conservators led by Ahmed Imam. The results of the first campaign (autumn 2018 to spring 2019) have been highly promising, as the complete and original colouration is now visible again in many parts.

Since these results offer a completely new approach to the temple decoration, the second objective of the project is a full photographic documentation of the current state of preservation, undertaken in co-operation with the Documentation Center (MoA), represented at the site by Mohamed Saad. In the long term, we intend to publish plate volumes of the entire decoration of the pronaos in order to set them next to the text volumes of the temple inscriptions so meticulously edited by Sauneron and thus to complete the publication of this famous temple.

In the following, we want to provide an insight into some of the most remarkable results of this first campaign. Recent conservation work began at the western part of the northern row of the ceiling decoration (Sauneron’s ‘Travée A’), much of which is taken up by the representation of the lunar phases (image above). Thanks to the cleaning efforts, the different phases of the completion of the wedjat-eye (indicating the different phases of the moon) can now be clearly distinguished. Apart from the moon, the solar bark and some constellations are also now visible in Travée A (image above right). In Sauneron’s publication, these images are not accompanied by inscriptions. It was therefore quite a surprise to find nearly every figure followed by a short caption. Executed not in relief but only in paint, they were not visible to Sauneron and hence not incorporated into his publications.

Turning to the columns, the cleaning and conservation of the northern columns has steadily progressed in recent months. Of

particular interest is the capital of the ‘midnorthern’ column (Sauneron’s ‘Column 7’). It represents a kind of orchard – a rare type of a column capital – apparently composed of a combination of grapevines and date palms (with a large quantity of dates hanging from the trees). Subtly intertwining, both plants are depicted with great accuracy. The capital is a good example from which to glean information on the colour system of the temple decoration: opaque red and yellow visually dominate, offset by the palms, painted green, and the grapes in blue (image next page, top left).

Beneath the capital of Sauneron’s ‘Column 1’ runs a frieze of alternating cartouches and winged scarabs (images next page, top centre and right). Again, the execution of the decoration is extremely detailed and accurate. Here, the dung beetle appears as a representation of the morning sun. At the same time, it can also be understood emblematically and be read as ‘live like Ra’, as is clearly suggested by the hieroglyphs. In

connection with the cartouches it can be read ‘May NN live like Ra’. The names given in the cartouches alternate between those of KhnumRa, Lord of Esna, Neith, Lady of Esna, the child-god Heka, and the emperor Trajan.

Conservation also made significant progress along the inner wall decoration. In the 4th (top) register of the northern part of the west wall, the goddess Neith is depicted in an offering scene (image opposite page). The recovered painting reveals many features that emphasise the character of the goddess. First, the goddess’s red dress is covered by a bead net made of blue and green beads set in a rhomboi pattern (this interpretation is supported by yellow round beads between the rhomboi). In this case however, the horizontal aspect is clearly accentuated as the blue and the green beads respectively form a zig-zag pattern, each in the shape of a waveline (with the phonetic value ‘n’). This is a ‘graphic pun’ referring to the name of Neith but perhaps also to the Primeval Water (Nun), in which Neith – in her manifestation as the cow Mehet-weret (‘the Great Flood’) – sets creation in motion. Furthermore, the pedestal of her throne is decorated with nine bow-and-arrow-pairs, attributes of the goddess (also shown in her left hand). At the same time, this also clearly refers to the concept of ‘stamping down the Nine Bows’, a traditional reference to the enemies of Egypt, a motif taken up again in the emblematic depiction on the throne. Here,

two enemies – one a man from the Levant, the other a Nubian – are bound at a stake. The depiction observes geographic directions, as the Nubian is looking south, the man from the Levant north.

Next to this offering scene, in the 4th register of the northern wall, Khnum-Ra, Lord of Esna, receives a crown offering together with his consort Menhit. Here, the colouration of the pharaoh (image left) – the emperor Trajan offering – is extremely well preserved, retaining even such details of crown and kilt that were only painted, rather than carved. This short overview presents some initial results of the exciting new work taking place at Esna temple, demonstrating its potential in future years.

• Hisham el-Leithy is head of the Documentation Center of the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities (MoA), Christian Leitz holds the chair of Egyptology at Tübingen University, Daniel von Recklinghausen is scientific collaborator of the project ‘The Temple as a Canon of Religious Literature’ of the Heidelberg Academy of Sciences and Humanities. All photos were taken by Ahmed Amin to whom the authors owe many thanks. The project on the decoration of the Esna temple and its conservation is kindly supported by Santander Consumer Bank and the Ancient Egypt Foundation.

Digging Diary 2019-20

Summaries of archaeological work undertaken in Egypt since spring 2019. Sites are arranged geographically from north to south. Field directors who would like reports of their work to appear in EA are asked to e-mail a short summary, with a website address if available, to the editor: jan.geisbusch@ees.ac.uk | Jan

G eisbusch

G eisbusch

LOWER EGYPT

Kom el-Gir and surroundings: From 8-19 Apr, the DAI Cairo mission under Robert Schiestl (Ludwig-MaximiliansUniv Munich) carried out a small-scale test excavation at Kom el-Gir, c. 4 km NE of Buto (Tell el-Fara’in) in the NW Delta. At the same time, colleagues from the Dpt. of Geography / Goethe Univ Frankfurt (Main) continued investigations of the landscape around the site, in particular with regard to the location of the course of the adjacent Nile branch. Five trenches were dug in the E part of the ancient settlement, where magnetic prospection had suggested the existence of a LR fort. This was confirmed by excavations of the SW corner revealing a projecting angular tower. The top of the ancient walls lies only about 7-10 cm below the current surface. The area around the fort was filled with settlement rubbish, mainly pottery and animal bones, dating from the PP to LR periods. Investigations into the ancient landscape continued 50-100 m N and NE of the settlement site. Auger cores confirmed the existence of a Nile branch running past the settlement in this area. www.dainst.org/ projekt/-/project-display/51318

Tell Basta: Work of the Tell Basta-Project (Univ of Würzburg), led by Eva LangeAthinodorou, continued at the site of the royal ka -temple of Pepy I (see EA 53). In the NW corner of the temple, levels of an impressive monumental building dating to an earlier period were discovered. The existence of spacious columned halls in that building, of which several phases from the middle of the 4th to the end of the 5th Dyn were identified, allow a preliminary identification as a provincial palace. If this identification is correct, Tell Basta would hold the earliest palatial building of the Nile Delta and probably all Egypt identified so far. At the same site, the remains of an administrative building with storage and food-processing facilities of the 6th Dyn were revealed. This structure belongs to the substitute buildings of the ka -temple. Geoarchaeological investigations around the temple of Bastet now provide firm evidence for the sacred canals of the temple described by Herodotus. In spring 2020, both sites will be investigated further. The project is currently sponsored by the Gerda-Henkel-Stiftung.

Athribis: The Athribis Project (Univ of Tübingen, MoA), led by Christian Leitz and directed in the field by Marcus Müller, continued its work in the Repit temple of Ptolemy XII and in a large trench outside the temple. The latter revealed more than 6,000 ostraca. In the 17th season (Oct 2018Apr 2019) the excavation of the pronaos was finished, proving that the columns and ceiling collapsed most likely during the 8th century AD. After clearance, a stone-tiled floor was laid for re-use of what is now an open-air space. A representative corridor with small columns of fired bricks gave access to two rows of mud-brick rooms, some of which would have served as working spaces, kitchens, and storage areas. At least two massive fires destroyed these buildings the ruins of which were then mainly used as animal shelter and rubbish dump, the latter revealing objects of daily life from the 8th to 11th centuries AD. The foundation fill underneath a completely destroyed room showed that the foundation platform at a depth of 5.4 m was not endto-end, unlike other rooms. Epigraphic work focused on finishing texts in various rooms for publication and the recording of newly discovered texts, e.g. dating the reliefs of the pronaos to Tiberius. A big conservation project, generously financed by ARCE, focused on two major walls with important reliefs and hieroglyphic texts.

Wadi al-Natrun (Deir al-Surian):

During the Mar 2019 season, work concentrated on the uncovering of paintings and conservation work in the E part of the Church of the Holy Virgin in the Coptic monastery of Deir al-Surian, especially the sanctuary. The dome over the altar, which was believed to have little or no surviving decoration, turned out to possess an almost completely preserved, 10th century painting. Its composition, divided into eight fields, contains theophanic scenes from the Old and New Testaments. Stripping the dome and walls below of the blank 18th century plaster also produced considerable new information on the history of the building. Parts of the original 7th century apse were found, carrying fragments of the Ascension scene that was here before the 10th century

rebuilding. Work on the E wall of the nave revealed paintings from the 7th, 8th, 10th and 13th centuries and previously concealed niches with decorative painted crosses, dating back to the 10th century. The project is run by the Univs of Warsaw and Amsterdam and led by Karel Innemée. www.facebook. com/DeirAlSurianConservationProject

Naukratis (Kom Ge’if): The port of Naukratis, founded during the 26th Dyn in the late 7th century BC, was the earliest, and for a period only, Greek port in Egypt. The BM’s seventh season in Mar/Apr 2019 under Ross Iain Thomas, with the generous support of the Honor Frost Foundation, excavated three areas of the settlement: 1) the E area of the ‘Hellenion’, in the Greek sanctuary precinct to the N of the settlement; 2) the river front to the W of the site; and 3) the ‘South Mound’ in the SW corner of the sanctuary of Amun-Ra (‘Great Temenos’). This was supplemented by geophysical work within the previously submerged lake area of the old town of Naukratis. Fieldwork was carried out with the assistance of local MoA inspectors who were trained in the use of survey equipment, excavation supervising, recording and find processing. The 2019

season produced significant new data on the layout of ancient Naukratis, enabling the precise location of all previous excavations undertaken. We also uncovered important stratigraphic, dating and topographic evidence for the settlement’s earliest phases. www.britishmuseum.org/research/ research_projects/all_current_projects/ naukratis_the_greeks_in_egypt.aspx

Saqqara : During Mar/Apr 2019, the joint Leiden-Turin Expedition to Saqqara (Museo Egizio, Turin; National Museum of Antiquities, Leiden) led by field directors Christian Greco, Lara Weiss and Paolo Del Vesco (deputy), continued excavations N of the tomb of Maya, treasurer of pharaoh Tutankhamun. The main concern was the removal of very large spoil heaps, originating from the 1980s and 90s fieldwork seasons, in order to prepare the area for the exploration of the new tomb discovered in 2018. These deposits were carefully excavated and the numerous finds retrieved will be studied further by specialists during the 2020 season. Similar to the previous season, the team included members of the 3D Survey Group of Politecnico di Milano who carried out a great number of photogrammetric surveys.

This season, the aims of the Politecnico group were threefold: 1) to support the excavation activities, recording the area, contexts and finds in line with the previous season; 2) to produce a digital surface model of the entire concession; and 3) to record previously excavated monumental tombs both on the surface and underground. Lastly, beside the restoration of the new finds, the monumental tombs, which had been heavily damaged by recent rainstorms, were carefully consolidated and covered with new protective layers. www.museoegizio.it/en/ explore/news/team-saqqara-2019/ • www. rmo.nl/onderzoek/opgravingsprojecten/ sakkara/

UPPER EGYPT

Deir el-Bersha : The KU Leuven mission under Harco Willems continued excavations from late Feb to late Apr to the S and W of the tomb of the nomarch Djehutihotep. Beside Djehutihotep’s tomb shaft, a second shaft with the same orientation and possibly belonging to a close relative or collaborator was excavated. The tomb had not reached a great depth as it hit upon an older tomb shaft during construction. 3D scanning of the area of the MK nomarch tombs continued. Several shafts that had been excavated earlier were re-opened to facilitate scanning. Geomorphological research continued on the W bank of the Nile in the el-Ashmunein region, in an endeavour to produce a cross section of augerings of the Nile Valley, with the objective to reconstruct the dynamics of the floodplain in past millennia.

Tell el-Amarna : On account of a delayed start, work by the Amarna Project under Barry Kemp and Anna Stevens (May/ Jun 2019) was largely confined to the Great Aten Temple. Further additions were made to the modern stonework that marks the outlines of the building, and more of the drift sand and other debris was cleared from the N and S wall trenches, allowing plans to be made of what is left of the original foundation layer of gypsum. A day was spent taking photographs at the North Harim of the Great Palace, sufficient to allow a photogrammetric record to be made. Jacquelyn Williamson continued her study of architectural and relief fragments from the earlier excavations at Kom el-Nana. www. amarnaproject.com

Karnak (precinct of Amun-Ra): The archaeological and epigraphic studies of the CFEETK continued under the supervision of Abd el-Sattar Badri and Luc Gabolde between Sep 2018 and Jun 2019. The restoration and conservation programme of the S magazines of the Akhmenu was implemented under the supervision of Laura Bontemps, with the support of the Kheops Fund for Archaeology.

Thanks to the same sponsor, the restoration of the quartzite statue of Amun of Tutankhamun was undertaken under the supervision of A. Garric, L. Antoine and M. Abd er-Radi with the aim to replace the concrete bust and left leg beam by copies of indurated sandstone shaped after original statues of the same reign. The background of the statue will be enhanced by the rebuilding of a portion of the Annals of Thutmose III, blocks of which were gathered and restored. In the ‘cachette courtyard’, A. Garric and his team have achieved the reconstruction of the E wall and implemented the rebuilding of the W wall. In the Osirian sector, the Ifao team led by L. Coulon and C. Giorgi continued the epigraphic study: archaeological research focused on the mud-brick walls and the surrounding structures. As part of the restoration activities, a secondary gate of the chapel of Osiris Wennefer Neb Djefau was rebuilt. The Karnak documentation programme, the online archive and lexical database continued under the supervision of J. Hourdin and S. Biston-Moulin. www. cfeetk.cnrs.fr

Karnak (precinct of Mut): The Brooklyn Museum Mut Expedition’s 2019 season in Feb, led by Richard Fazzini, concentrated on the First Court of Temple A, in the NE corner of the site. The S side of the court was cleared, revealing what are probably the remains of five sphinx bases with later structures built over them. The front two rooms of the Nitocris Chapel in the court’s SE corner were fully cleared, revealing the original paving in the first room. Five of the eight columns on the N side of the court were re-erected on new bases. The rear half of a sphinx on the W side of the court was restored; together with the upper half of a statue of Ramesses II, it was placed on mastabas, and the badlydeteriorated lower halves of two granite royal statues were protected from windblown soil. The study of the site’s Sekhmet statues and the Montuemhat Crypt in the Mut temple continued. www.brooklynmuseum.org/ features/mut (site description, reports); www.brooklynmuseum.tumblr.com/tagged/ mutdig (dig diary)

Dra Abu el-Naga North (TT 1112): The Spanish mission (CSIC) at Dra Abu el-Naga North, directed by José M. Galán, continued the excavations SW of the tombchapel of Djehuty (TT 11) in Jan/Feb 2019, at the open courtyard where an early 12th Dyn funerary garden had been brought to light in 2017 (see EA 54). Archaeologists and geologists focused on the documentation of the layers of thin sand that had sealed the garden and protected it from human activity taking place in the area during the SIP. At this time, several funerary shafts and mud-brick offering chapels were built. One of the shafts was excavated and, despite the fact that it had been robbed in antiquity, a pair of engraved leather sandals was found, next to a pair of

leather balls tied together by a string. A new mud-brick chapel was unearthed, together with six inscribed stick-shabtis dedicated to Ahmose. One of them, still wrapped in linen, bears the name Ahmose-Sapair. www. excavacionegipto.com

Asasif (TT 414) : The principal aim of the Ankh-Hor Project of Ludwig-Maximilians Univ Munich is the complete analysis of finds excavated under the directorship of Manfred Bietak 1969 to 1979 in the Asasif, first of all from TT 414, the monumental tomb of Ankh-Hor (26th Dyn). Large

about the possible burial place of MeritNeith within TT 414. www.ankhhorproject. wordpress.com

Valley of the Kings: This season’s work in Jun 2019 of the Amenmesse Project (KV 10 / KV 63) (MoA and AUC) had four foci: 1) finishing the documentation of the ceramic materials from KV 63; 2) continuing the organisation and documentation of the ceramics from KV 10; 3) recording the different phases of decoration and re-use of KV 10; and 4) cataloguing and studying the material from KV 63. The team, led by Salima Ikram, managed to accomplish its goals, with the recording of the tomb walls being particularly interesting. The original decorative scheme of the tomb when it was cut for Amenmesse is slowly being

Below:

numbers of finds from these excavations are still unpublished and were left on site in the mission’s storeroom. This material holds rich potential for understanding the funerary customs in the LP, the Ptolemaic and Roman era. During the 2019 season in Feb/Mar, led by field director Julia Budka, the documentation of the finds continued, with a focus on coffins, including a large scale conservation programme. The wooden coffins belong both to primary burials of the family of Ankh-Hor and to secondary burials of Amun priests, mostly dating to the 4th and 3rd centuries BC. Some pieces were identified for the first time and linked with documentation from the 1970s, as illustrated by the side board of the qrsw coffin of Merit-Neith, daughter of Ankh-Hor, published in 1982. A new small fragment from the vaulted lid was found in the magazine, offering fresh information

reconstructed, while the removal of most of this carving can also be recorded, including the identification of different tools as well as different artisans. Some of the schema of decoration for Queens Baketwernel and Takhat are also being identified, with the hope that the whole schema will be reconstructible.

Berenike: Excavations by the Univ of Delaware (USA) and the PCMA (Univ of Warsaw) under the direction of Steven E. Sidebotham and Iwona Zych took place in Jan/Feb 2019 in five locations: 1) a PP hydraulic area / ER cemetery; 2) a pet necropolis; 3) the ‘Northern Complex’; 4) the tetrastylon; and 5) the main Isis temple. After abandonment, the PP hydraulic facility became a cemetery in the ER era. Portions of a wooden sarcophagus partially made of teak have survived. Some burials contained

ceramic vessels as grave goods. One had a silver ring with decorated intaglio. There was new information about 4th to 5th centuries AD activities. Evidence for religious functions in the ‘Northern Complex’ included sculptural and epigraphic testimony for cults of Horus and Isis-Serapis, the latter appearing on an inscription recording a Blemmye king. Excavations continued at the 4th century or later tetrastylon at the intersection of major N-S/E-W streets. Excavations in the main Isis-Serapis temple exposed most of the interior, the propylon and areas abutting the temple exterior. Additional epigraphic evidence in Greek and hieroglyphs, and sculptural remains in wood, bronze and stone now augment the knowledge of this major structure for the period from the 1st century AD until late antiquity. Excavations in the propylon documented fragments of a life-sized stone statue of the Meroitic deity Sebiumeker. The inscription mentioning a Blemmye king, statue fragments depicting Sebiumeker and images of other Meroitic deities indicate a more complicated history of Berenike than previously assumed.

Abbreviations:

Technical terms: PD Predynastic; EDP Early Dynastic Period; OK Old Kingdom; FIP First Intermediate Period; MK Middle Kingdom; SIP Second Intermediate Period; NK New Kingdom; TIP Third Intermediate Period; LP Late Period; PP Ptolemaic Period; GR Graeco-Roman; ER Early Roman; LR Late Roman; ERT Electrical Resistance Tomography; FTIR Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy; GPR Ground Penetrating Radar; pXRF portable X-ray fluorescence.

Institutes and Research Centres: AEHAF Ancient Egyptian Heritage and Archaeology Fund; AUC American University in Cairo; BM British Museum; CEAlex Centre d’Études Alexandrines; CEFB Centro di Egittologia Francesco Ballerini; CFEETK Franco-Egyptian Centre, Karnak; CNRS (USR) French National Research Centre (Research Groups); CSIC Spanish National Research Council; DAI German Archaeological Institute, Cairo; IAJU Institute of Archaeology Jagiellonian University, Cracow; IFAO French Archaeological Institute, Cairo; MEAE Ministère de l’Europe et des Affaires Etrangères; MMA Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; MoA Ministry of State for Antiquities, Egypt; NCAM National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums of the Sudan OI Oriental Institute (University of Chicago); PCMA Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology, Cairo; SwissInst Swiss Institute for Architectural Research and Archaeology, Cairo.

An Egyptian grand cru: wine production at Plinthine

Recent archaeological discoveries as well as archaeobotanical and environmental studies in Plinthine shed new light on wine production at this small village on the taenia ridge between the Mediterranean Sea and Lake Mareotis, writes Bérangère Redon . Viticulture was practised here from the New Kingdom to the Ptolemaic period. For the first time, we gain information on the grape varieties and winemaking process in an area whose wines were once famous but are still little known within archaeology.

Wine production in ancient Egypt

Wine in ancient Egypt? The country is not renowned for its wines in Pharaonic times, and in the classical literature the Egyptians are considered as beer drinkers. The famous historian of the 5th century BC, Herodotus, even states that the inhabitants of the country did not grow vines on their soil (II, 77). Winemaking and -consumption in Egypt is usually associated with the arrival of wine-drinking populations in Egypt after the conquest of Alexander the Great in 331 BC, for which there are indeed numerous papyrological and archaeological data (dozens of wineries have been excavated, mainly of the Roman and Byzantine periods).

However, viticulture is evidenced in Egypt from the Predynastic period and the Old

Kingdom onward, especially on the fringes of the Nile delta where the first vines might have been imported from the Near East. While mentioned in written sources, represented on paintings adorning the tombs of the Theban valley, and evoked by the thousands of labels found with the jars that contained the precious liquid, the production of wine in pharaonic Egypt has never been studied in the field. This is because until recently, no archaeological evidence of a pharaonic winery has been found, other than a very poorly preserved example at Tell el-Dab’a

One of the most famous Egyptian vintages was grown on the territory called ‘the Western River’, mentioned on a few dozens of jar labels found in Tell el-Amarna (representing more than 70 percent of the jar labels ever found at the

View from Kom elNogous to the west, with fig trees now replacing the ancient vineyards. The Osiris temple of Taposiris is visible in the background. Photo: MFTMP / B. RedonBelow: plan of Kom el-Nugus / Plinthine and its vicinity, with the find spots of wine-production remains.

site). The ‘Western River’ probably merged with or included the Mareotis region, on the shores of Lake Mareotis (nowadays Maryut), located at the gates of Alexandria and well known for its wine production in Roman and Byzantine times. The quality of the Mareotis wine is praised by Latin poets, such as Virgil and Horace. According to them, it was white, sweet, and aromatic. Strabo even says that the ancients let the Mareotis

wine age (XVII, 1, 14). Among the vintages produced in the region, the wine of the taenia, the sandstone ridge separating the Mediterranean Sea from Lake Mareotis, was judged of better quality than the wine from the southern Mareotis area by Athenaeus, an Egyptian author of the 2nd century AD. According to him, ‘the taeniotic wine, in addition to being sweet, [was] somewhat spicy and slightly astringent’ (I, 33).

Plinthine – a wine-producing village

With the support of the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the French Institute of Oriental Archaeology (Ifao), and the Arpamed fund, the French mission of Taposiris Magna and Plinthine (MFTMP) recently launched a project dedicated to the study of the wine production of a taeniotic site – Plinthine – over the longue durée from the pharaonic period to the end of Ptolemaic era. Coupling soil analyses, the study of grape varieties and excavations, the analysis focus on the whole production chain, from the grape seed to the jar.

Plinthine is remarkably situated on the shores of the Mediterranean Sea and Lake Maryut, 2 km east of Taposiris Magna, a well-known city occupied from the Ptolemaic period to early medieval times, in the extreme north-west of what Herodotus considered as the territory of Egypt. The site consists of a large, horseshoe-shaped kom (Kom el-Nugus), 11 m high, atop the ridge. Our excavations have shown traces of occupation from the Late New Kingdom to the Late Ptolemaic or Early Roman period. It overlooks a village, built on the southern slope of the ridge, looking toward Lake Mareotis, whose last phase of occupation – the only one we have studied so far – dates back to the Hellenistic period. Dated to the same period, the necropolis of Plinthine is situated 500 m to the west. Between the kom

and the necropolis, scattered pottery dated to the New Kingdom is visible on the surface.

Three phases of viticulture at Plinthine

Interestingly, Hellanikos, a Greek author of the 5th century BC (quoted by Athenaeus I, 60), reports that viticulture was invented at Plinthine. This is likely a legend, but our recent finds show that wine production began well before the mention of Hellanikos, probably during the New Kingdom, and that this tradition lasted for more than a millennium, with unexpected intensity.

First evidence was discovered in 2015, during a survey in the ‘New Kingdom area’, where several ovens and ceramics, including a wine jar stamped with the name of the eldest daughter of Akhenaten, Merytaten, were found. Besides other artefacts (among them a limestone stela of Sety II) that attest a royal presence on the site during the next dynasty,

the stamped wine jar may suggest that a royal vineyard was cultivated at Plinthine during the Eighteenth Dynasty.

After a period not well-documented on the site so far, wine production clearly intensifies again during the Twenty-sixth Dynasty, as

Other tomb paintings show that the men were singing while pressing the grapes, and hold poles or strings attached to the roof or to the hips or shoulders of their neighbours in order not to slip on the grapes. Treading was indeed not all that easy, as the quick onset of fermentation while grapes were being pressed meant that workers were probably a little drunk while pressing.

The third period of wine production evidenced at Plinthine dates to the Ptolemaic period. A few decades after Alexander the Great’s conquest of Egypt, a community of new inhabitants of Hellenic origin settled on the site, as shown by their funerary customs

shown by the discovery of an exceptionally well-preserved grape grinder, whose construction can be securely dated to the second half of the 7th century BC. It is located in a vaulted room that belongs to a complex building still only partly excavated, and is built in a very fine local limestone, covered with mortar. The grinder consisted of a raised treading platform (1.89 x 2.14 m) where the grapes were pressed underfoot by several people, and a monolithic vat of 9 hl into which the juice flowed from the platform through a drain. A unique example in pharaonic Egypt, its closest parallels can be found in the paintings that adorned the tomb walls of the Valley of Nobles in Thebes, in particular in the tomb of Nakht (TT 52). It is also very similar to the winery depicted in the Petosiris tomb, dated to the early Hellenistic period, except for the lion-head drain, which becomes common only during the Graeco-Roman period in Egypt.

and offerings, and some rare inscriptions. They clearly perpetuated the wine tradition of Plinthine, as shown by the discovery of the only wine-producing villa in Mareotis that can securely be dated to the Ptolemaic period. It is located at the fringes of the necropolis and is organised around a grape grinder, similar to the earlier, Saite one (with a treading platform and a deep vat for the juice), but larger. The work conducted by Olivier Callot (CNRS, Lyon) and then Louis Dautais (Université Montpellier III) show that it was abandoned in the second half of the Ptolemaic period. Like the Saite one, the Ptolemaic wine factory was housed within a larger building, which might have been a private residence, indicating that wine production occurred in a domestic context. The Saite treading platform of the 7th century BC could likley produce 400 l in one go, the capacity of the Ptolemaic platform might have been twice as much. Both represent significant quantities, though, of course, they are small compared to the later large-scale production of some villas of the Roman world.

Soil analysis and wine quality

Such continuity in the Plinthine wine production is due above all to the quality of the terroir and the composition of soils that seem to be partiularly suitable for viticulture, as demonstrated by the geomorphological analyses conducted by Maël Crépy (post-doc CNRS): the soil is composed of a mix of substratum fragments, fine siliceous sand coming from the desert to the south and coarse calcareous sand originating from the seashore, with a proportion of silt and clay that is lower in the upper part of the ridge than nearer the lake, resulting in good drainage characteristics and making the soil easier to work. It is also significant that the samples taken at Plinthine are less alkaline than those coming from Taposiris Magna. Plinthine was definitely the best place in the area to produce wine of quality.

This undoubtedly stimulated the central role played by viticulture at the site, in particular during the Saite and Ptolemaic periods, as demonstrated by the discovery of thousands of grape pips, stems or fragments of grape skin and vinegrape charcoal fragments during our excavations (no New Kingdom levels have been sampled so far; probable Third Intermediate Period layers with grape seeds

and charcoal have been studied, but their chronology is not well established and they were not taken into account for this article). All the soil samples analyzed by Charlène Bouchaud (CNRS) and Menna el-Dorry (MoA and IFAO), and dated to these two periods contain grape remains, while other species grown at the site are few and derive solely from inhabitants’ food and wood requirements. The raison d’être of the village seems indeed to have been the production of wine, at least under the Saite and Ptolemaic dynasties.

Was the Plinthine wine a grand cru or a piquette? Archaeobotanical research has not yet made it clear. The morphometric study conducted by Clémence Pagnoux (post-doc École française d’Athènes) shows that numerous grape varieties were grown and

pressed at Plinthine during the Twenty-sixth Dynasty and in the Ptolemaic period, with, respectively, 28 and 15 different grape varieties identified so far, ranging from species close to the wild vine to varieties well-known elsewhere in the Middle East or Greece. The cépages assemblage change between the two periods may perhaps reflect the evolution of the customers’ taste, though it could also be due to technological and techno-biological transfers that took place after the Greek conquest, when many Hellenes (in the broad sense of the word) came to settle in Egypt and especially in Alexandria and the nearby Mareotis area. However, the evolution of the diversity of the cultivated grapes is also a manifestation of attempts to adapt varieties to the Plinthine terroir.

Trading networks

Thanks to the production of wine on its slopes during pharaonic times, Plinthine was at the heart of commercial networks since the precious beverage was first produced, initially for consumers living in the Nile Valley. While not yet identified with certainty, the Plinthine cru is likely to be one of the wines well-known from Egyptian sources, drunk at the tables of the pharaohs and the social elites as ‘wine of the Western River’. Probably favoured by its location on the Mediterranean coast, Plinthine was also part of Mediterranean trade during the Saite period, and the local production of wine in Plinthine is contemporaneous with massive imports of wine amphorae from eastern Greece (Samos, Chios, Lesbos, Clazomenes, Athens, etc.), Cyprus and the Phoenician world that are currently studied by Mikaël Pesenti. This raises many questions about the techno-biological transfers these exchanges might have facilitated before the Ptolemaic period and about the interface role that Plinthine certainly played at a time when Egypt was opening up to the Mediterranean. This is one of the questions the next campaigns will try to answer.

• Bérangère Redon (CNRS, Lyon) is director of the French mission of Taposiris Magna and Plinthine (MFTMP). More information on the mission can be found at: www.taposiris.hypotheses.org

Psamtik I in Heliopolis