EGYPTIAN ARCHAEOLOGY

Tomb of Khuwy at Djedkare’s Royal Cemetery

Mohamed Megahed

A Colossal Portrait of Amenhotep III

Hourig Sourouzian

Discovery of the Lost Golden City

Zahi Hawass

ISSUE 59 • AUTUMN 2021 • £5.95

This two week tour, staying in top hotels throughout, begins in Cairo with in-depth tours of Saqqara,The Giza Plateau and Old Cairo.We fly to the Southern City of Aswan with time to visit Abu Simbel, Philae and Qubbet el Hawa. Driving to Luxor we stop at the vast Temple at Edfu and enter the striking tombs at el Kab.

Abu Simbel

The Great Pyramid at Giza

The Valley of The Kings

DEPARTING 6th DECEMBER 2022

THE GREAT MONUMENTS TOUR

We continue our journey in Luxor with five nights at the elegant and nostalgic Old Winter Palace, Garden Pavilion Wing. Visits include the Valley of The Kings, the Ramesseum, the Temple of Hatshepsut, Deir el Medina, the Colossi, Luxor and Karnak Temples, and much more. We even take time to relax and enjoy a lunch from The Old Winter Palace while sailing the Nile on a traditional Felucca.

This is the perfect tour for those wanting to discover the most spectacular sites in Egypt

Dr Campbell Price is Curator of Egypt and Sudan at Manchester Museum. Campbell is currently the Chair of Trustees at the Egypt Exploration Society. He is an Honorary Research Fellow at the university of Liverpool, and has undertaken fieldwork in Egypt at Zawiyet Umm el-Rakham, Saqqara and the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

CALL NOW TO BOOK +44 (0)333 335 9494 OR GO TO www.ancient.co.uk ancient world tours

Tour price:

Single supplement

Standard

£4,200

£392

AWT is an agent of Jules Verne. These Air Holiday packages are ATOL Protected by the Civil Aviation Authority. JV’s ATOL No.11234 JULES VERNE The Distillery, Dunton, Norfolk NR21 7PG UK

WITH DR CAMPBELL PRICE

EGYPTIAN ARCHAEOLOGY

No. 59 Autumn 2021

www.ees.ac.uk

Editor Charlotte Jordan

Editorial Advisers

Omniya Abdel Barr

Heba Abd El-Gawad

Anna Garnett

Loretta Kilroe

Roberta Mazza

Ahmed Nakshara

Campbell Price

Advertising sales

Phone: +44 (0)20 7242 1880

E-mail: ea@ees.ac.uk

Distribution

Phone: +44 (0)20 7242 1880

E-mail: contact@ees.ac.uk

Website: www.ees.ac.uk

Published twice a year by The Egypt Exploration Society

3 Doughty Mews London WC1N 2PG

United Kingdom

Registered Charity, No. 212384

A Limited Company registered in England, No. 25816

Design by Nim Design Ltd

Set in InDesign CC 2021 by Charlotte Jordan

Printed by Intercity Communications Ltd, 49 Mowlem Street, London E2 9HE

© The Egypt Exploration Society and the contributors. No part of this publication may be reproduced without prior permission of the publishers.

The opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the aims or concerns of the Egypt Exploration Society.

ISSN 0962 2837

Read EA back issues online at www.issuu.com/theees

Egyptian Archaeology 59 marks a change in editorship. Jan Geisbusch expanded and innovated the magazine during his time in post, and I am honoured to build upon this foundation he laid as the next Editor of EA . Over the upcoming issues, you will notice some changes, one being the final page of this magazine—a fun finish to your reading. Members will now find the Society’s annual Impact Report available online (www.ees.ac.uk), where you can read about how we tackled the global health crisis. One of many steps to expand our online service provision. I am pleased to start working on the magazine at such an important stage in its 30-year history, and I hope you enjoy reading a broad range of topics from diverse perspectives. Please contact me at ea@ees.ac.uk if you would like to contribute to future magazines.

This issue begins with a recent discovery in Egypt: the ‘Lost Golden City’. Here, Zahi Hawass provides an in-depth discussion of a newly uncovered city of Amenhotep III. After two articles on settlement archaeology, we move on to three papers exploring burial customs in Egypt, where Elsayed Eltalhawy presents Kôm el-Khilgan from the Predynastic to the Roman era. Timely research by Ahmed Nakshara considers the transportation of museum objects traced from our own archives into the soon-to-be-opened Grand Egyptian Museum. I am particularly excited to feature the first published images of recently discovered colossi at Amenhotep III’s mortuary temple (as seen on the cover) by Hourig Sourouzian, as well as the tomb of Baqet II at Beni Hassan by Naguib Kanawati and co-authors. Finally, Mohamed Megahed’s project at Saqqara, partially funded by the EES, presents the recently excavated scenes of the earliest known Old Kingdom non-royal decorated tomb substructure.

Charlotte Jordan

1 EGYPTIAN ARCHAEOLOGY ISSUE NO 59 AUTUMN 2021

Editorial

Above: General view of ‘The Dazzling Aten’ City; see p. 4–7 (photo: Zahi Hawass). Cover: Head of the North Colossus of Amenhotep III at the Third Pylon at Kôm el-Hettan; see p. 30–36 (photo: © The Colossi of Memnon and Amenhotep III Temple Conservation Project. Photo: Antoine Chéné).

As the world starts to recover from the Covid pandemic, so does research and archaeology. This issue is bursting with the latest discoveries in Egypt, EES research projects, as well as the return of our Digging Diary.

2

The funerary temple and pyramid of Djedkare. © Djedkare Project, see p. 42-45.

4

8

13

16 Resurrection in Panopolis

20 Kôm el-Khilgan: A 4,000 Year History

24 Digging Diary 2021

26 Fr om in situ to the Grand Egyptian Museum

30 A Colossal Portrait of Amenhotep III

37 G overnor Baqet II at Beni Hassan

42 Tomb of Khuwy at Djedkare’s Royal Cemetery

46 B ookshelf

Anna Stevens, Amarna: A Guide to the Ancient City of Akhetaten

Eleanor Dobson, Writing the Sphinx: Literature, Culture and Egyptology

Kathlyn M. Cooney, Coffin Commerce

48 Puzzle Page

Wordsearch and “Egypt’s Dispersed Heritage” Project Comic

3 EGYPTIAN ARCHAEOLOGY ISSUE NO 59 AUTUMN 2021 Contents

Zahi Hawass

Discovery of the Lost Golden City

Marc Maillot

T he Archaeological site of Damboya

Ayman Wahby

Mastaba Tombs at Tell Tebilla

Wahid Omran, Ashraf Okasha and Abdullah Abu-Gebel

Elsayed F. Eltalhawy

Archaeological work undertaken in Egypt and Sudan since Spring

Ahmed Nakshara

Hourig Sourouzian

Naguib Kanawati, Eman Khalifa and Martin Bommas

Mohamed Megahed

Discovery of the Lost Golden City

Dazzling Aten’ of Amenhotep III

Zahi Hawass reveals the latest discoveries from the newly uncovered city, ‘The Dazzling Aten’, and the information it provides about the reign of Amenhotep III (c. 1390–1352 bce). While reported as the largest settlement to have been found in Egypt, it provides significant evidence towards the understanding of daily life, the central administration of Egypt during this period, and further evidence for the pharaoh’s three Sed -festivals.

Excavations began in 2020 to the north of the temple of Medinet Habu, the funerary temple of Ramesses III (c. 1187–1156 bce) on the west bank of the Nile. The goal was to find the funerary temple of Tutankhamun since the temple of Ay and Horemheb had previously been located in this area. However, the city was a totally unexpected find! Two specific dates are preserved from the city, years 26 (c. 1364 bce) and 37 (c. 1353 bce) of Amenhotep III’s reign. The settlement is therefore contemporary with a similar settlement found during French-led excavations 100 m to the west. Upcoming work in September 2021 is

expected to confirm whether this city is connected with these structures. Stratigraphy uncovered at the site so far indicates that the settlement had been untouched since antiquity giving great potential for new information.

During antiquity, the city was called Tehen Aten, meaning ‘The Dazzling Aten’, as evidenced by the discovery of clay seals bearing this name. One of the epithets of Amenhotep III was ‘The Dazzling Aten’, as attested from an inscription written on the king’s quartzite statue found in the Luxor temple statue cache, now in Luxor Museum. The name of the city was also a popular title for many princes and high officials of the 18th Dynasty and can be found in private tombs in Valley A and Valley 300, both located at the western valley of the west bank of Thebes. Amenhotep III also named his palaces ‘The Dazzling Aten’. Inside the city, the team uncovered a wall drawing, in white ink, of the Aten. This drawing, and the name, suggests that focus upon the worship of the Aten started during the reign of Amenhotep III. Despite this promotion of the Aten, there is no indication that the priests of Amun objected as Amenhotep III maintained his connection with Amun and the other gods at this time. In future seasons of work, we expect to locate the boundaries of the whole settlement and reveal more critical information to improve our understanding of people’s lives during this era of Egypt’s history.

4

‘The

Seal depicting the name of the city: ‘The Dazzling Aten’, no. 47.

City Overview

The current plan of the city contains one large, wide street in the centre, surrounded by serpentine (sinusoidal) walls. After further examination, we concluded that the city was divided into three districts:

1. T he living area

2. T he administrative area

3. T he industrial area

The level of preservation was as if the ancient inhabitants had left the town just days earlier. In the living area, there were remarkably wellpreserved houses reaching a height of 3.5 m divided by several streets. Many items of daily life and industry were found within these houses, including hammers and weaving tools. The date of the city was confirmed through inscriptions found on rings, scarabs, decorated pottery vessels, and mudbricks, all containing the name of Amenhotep III in this area. Domestic finds included spinning and weaving tools. Slag, the waste material from metalworking, was also seen as well as other signs of metalworking activity.

On the southern side of the settlement, we found a bakery and an area for cooking, including ovens and large storage vessels. From the size of this baking and cooking area, it is apparent that it served many workers and officials living in or around the settlement.

Serpentine walls protected the administrative part of the settlement. Only one entrance has been found connecting this area to the others. This entrance controlled access to the administrative quarters leading to a series of interior corridors and large units of wellorganised houses.

Sinusoidal walls are rare in ancient Egyptian architecture and are most often found in Middle Kingdom (c. 2055–1650 bce) contexts. The form seems to have been revitalised during the Amarna Period (c. 1346–1336 bce) and this evidence is some of the earliest from this period.

The third section of the city was the industrial area that perhaps supplied goods for trading beyond the local area. It includes a workshop that produced mudbricks for constructing the

5 EGYPTIAN ARCHAEOLOGY ISSUE NO 59 AUTUMN 2021

DISCOVERY OF THE LOST GOLDEN CITY

General view of ‘The Dazzling Aten’ City.

King’s palace at Malkata and his funerary temple at Kôm el-Hettan to the north of the city (see p. 30–36). The mudbricks contain stamps with the cartouche of Amenhotep III (Nb-mAat-Ra ). The storage areas and extensive workshops in this area were connected to a small store for grain storage. Leather that preserved goat hair was also found.

Burials have been found during the excavations. To the north of the settlement, a large cemetery was revealed. It consists of a group of differing sized tombs that can be accessed through stairs carved into the rock. Only one tomb was opened, and its first chamber reached, which contained four canopic jars. We will investigate the other tombs during our next season. Another burial, found in one of the rooms within the industrial district, is being investigated further. Here, a skeleton was found in an unusual position, stretched with his hands to his sides and the remains of a rope wrapped around his knees. There were also two cow burials inside the rooms, but we do not yet know the exact purpose of these burials. They may be representations of the goddess Hathor, perhaps relating to several amulets linked to her also discovered at the site.

Notable Finds

On the other side of the industrial section, more than 100 moulds were found. These were used for the production of amulets and decorative components. Many of

these finished components were also found at the site, including the eye of Horus (wedjat) and scarabs. It is not yet clear whether these represent cult activity or are leftovers from a corpus produced in the city for distribution elsewhere. A seal inscription discovered in the western part of the town reads: gm Atn ankh m mAat meaning “The Aten who lives on ma’at (truth) is found”. This find may provide stronger evidence that a temple for the Aten existed in this area, rather than simply acting as an industrial centre.

Sed -festivals were usually celebrated by the pharaoh after 30 years of rule, and then repeated every three years afterwards. The most interesting discovery demonstrating the number of Sed -festivals Amenhotep III celebrated is the hieroglyphic inscription on a jar, which can be read: “Year 37, dressed meat for the third Sed -festival from the slaughtering house of the stockyard of Kha, made by the butcher Iuwy”. The name of Kha was also found on a meat jar, alongside nine further jars for the storage of meat. The tomb of Kha was found intact at Deir el-Medina, objects from which are now in the Museo Egizio in Turin.

6

Left: Clay seal with the name of King Amenhotep III: Nb-mAat-Ra, no. 1515.

Group of blue-painted pottery vessels with floral decoration.

Right: An amulet mould, no. 239.

He was a royal scribe, overseer of works and supervisor of the palace of Amenhotep III. This meat was used for the third jubilee or Sedfestival (Hb-sd ) of the King, in the 37th year of his reign.

Thousands of pottery sherds covered almost one acre of land, and a large amount of metal and glass was also discovered. Approximately 1,000 artefacts were found in the city, including many complete ceramic vessels displaying some of the best examples of New Kingdom decorated pottery yet found, including decoration using blue paint and gazelles modelled in clay. Several statuettes of Queen Tiye, the chief wife of Amenhotep III, were also discovered at the site.

Next steps

Excavations will continue in September 2021 on the west side of the city where preliminary investigations suggest that the city continues westwards. The further excavation of this site will undoubtedly contribute to our understanding of the most remarkable years of the reign of Amenhotep III. The site is especially interesting due to the scarcity of sites revealing ancient daily life in the years immediately preceding the Amarna Period, a subject which has been largely uncharted until

now. Subsequent works seek to find out more about those that lived in the settlement and why it was eventually abandoned.

7 EGYPTIAN ARCHAEOLOGY ISSUE NO 59 AUTUMN 2021

• Zahi Hawass is an Egyptian archaeologist and former Secretary General of Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities (SCA). He initiated the Egyptian Mummy Project, which used forensic techniques to study both royal and non-royal mummified human remains.

Hieratic inscription on a jar with the name of the royal scribe Kha and butcher Iuwy. Zahi Hawass on site.

DISCOVERY OF THE LOST GOLDEN CITY

Photo: Karoline Amaury

The Archaeological Site of Damboya

A Royal City of the Meroitic Empire

The Meroitic Empire (c. 4th Century bce –4th Century ce), one of the oldest political structures in sub-Saharan Africa, was situated in the Middle Nile region of Sudan. Marc Maillot reports on the latest findings at Damboya; a site long recognised for its importance towards ancient urbanism in Sudanese archaeology but not examined further until now.

The archaeological site of Damboya, identified by Friedrich Hinkel and investigated in 2002 by Patrice Lenoble and Vincent Rondot, is located in Sudan, 270 km north of Khartoum, near Shendi, into the concession of El-Hassa (1.7 km) of which it is a component. The Louvre Museum asked the National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums (NCAM), previously known as the Sudan Antiquities Service, to integrate this concession into the department of Egyptian antiquities in 2020. Marc Maillot, current director of the mission, had expressed the wish to open an archaeological excavation in Damboya, as part of his program as director of the French Archaeological Unit in Sudan (SFDAS). Therefore, a scientific cooperation agreement was signed between the Louvre Museum and the SFDAS, so that the Damboya excavation could begin in 2020 under the supervision of the SFDAS. The potential of the archaeological site of Damboya had already been identified for a long time. The results obtained following the magnetometric survey carried out in 2008 on the central part of the site were promising for an in-depth study of urban settlements on the banks of the Nile in central Sudan, in connection with one of the major sites of the Meroitic Period, El-Hassa.

Results of the first season enabled the SFDAS archaeological team to continue excavating the most promising sectors for a long-term study on the settlement of Damboya. Two campaigns have been performed so far, from February until March each year. Two sectors are the focus of archaeological activities, A and E, chosen for their position framing the main hill of the site.

8

Topographical Map of Damboya and excavated areas.

Sector A

Sector A was mainly occupied by two Meroitic cultic structures, a temple and a chapel. The southern hill of Damboya has a diameter of 40 m, and a preserved elevation of 1.10 m. Covered with red brick fragments, small grindstones, ceramic and some scattered bones, it presents all aspects of a hill created from human settlement in central Sudan. Successive surveys carried out on the site indicated that the ceramic was predominantly dated from the Meroitic Period, which the results obtained confirm (1st-2 nd Century ce). After significant surface clearing, the first courses of the walls began to appear. The strategy was to record a complete plan of the preserved structures.

The best-preserved building in Sector A is a rectangular structure in red brick orientated east-west, measuring 16.30 m long x 7.20 m wide. Four walls (F003, 6, 7, 46), frame an internal space of 5 x 15.7 m. These four walls are 1.10 m wide, with masonry in a header/stretcher pattern. Wall F006 widens towards the south-east, up to 1.30 m wide, because it cuts through a previous mudbrick structure but partially uses it as a foundation (F026). It then forms an angle with wall F28, particularly interesting because it corresponds to an internal wall of the tripartite

temple. Indeed, wall F029 was potentially chained with F28 to form a single foundation wall, even if the connection is now missing. The complete plan of the temple is then enclosed by wall F046 with its facade at right angles, without a Pylon. It confirms the tripartite plan of the temple, composed of, from east to west, a first narrow room (3.80 x 4.01 m), then a second central room (2.76 x 3.97 m), and finally the sanctuary, closed by the wall F003 (4 x 5.02 m).

On the other side of wall F003 towards the west, a defined destruction level comprising many fragments of lime plaster, a concentration of gold leaves, faience and fragments of boxes in glazed

9 EGYPTIAN ARCHAEOLOGY ISSUE NO 59 AUTUMN 2021

General plan of Sector A.

General view of the Meroitic red brick temple.

THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE OF DAMBOYA

Photo: © SFDAS/Musée du Louvre

ceramic tiles is present. This context (US10) is remarkable beyond this particular concentration of material, as it includes a large number of charcoals, fragments of vitrified brick, and evenly burnt sand. There is every reason to believe that a fire partially damaged the temple in this crucial area just west of its outer facing, where most of the preserved decoration has been found. A sample of charcoal was taken in 2020 for C14 analysis, which allowed us to obtain absolute dating of the destruction of the temple to the second half of the 1st Century ce

Wall F017 follows the exact orientation of wall F007, they are separated by a passage 1.90 m wide, forming a corridor around the exterior walls of the temple (13.02 x 12.31 m). Wall F017 extends towards the north-west in a straight line, then creates a right angle with another wall orientated south-north, F051, to frame the western part of the temple and, more particularly, the walls F007 and F003. This U-shaped corridor surrounding the temple is also symmetrical to the south, as demonstrated by the discovery of wall AF050, strictly parallel to wall F006. The 2021 season also located a side entrance staircase to the north-east of the hill, with the discovery of the AF037 wall. It forms a narrow passage with the AF017 wall to then turn inside the corridor

surrounding the temple. The top of the northwest section of F037 is also plastered, which indicates that it did not rise higher in elevation and opened onto an outdoor area.

The temple is prolonged to the west by a complex (22.78 x 21.05 m) accessible by a ramp (F052), unfortunately heavily damaged. This ramp abuts against a long wall (AF053), delimiting a building of 16.52 x 6.53 m. This wall F053 is also flanked by three other walls, AF054–56, which mark a tripartite plan of three rooms. This is enclosed to the south by wall F056, which shows red bricks on the edge at the corner, marking the presence of an external angle. This angle is placed in the immediate vicinity of another set of the complex, orientated east-west, which corresponds to a row of storerooms (14.86 x 4.53 m). This row is organised according to a rectangular plan divided into five parts, including a larger central room having only one course preserved in elevation. This row is then attached to the corridor of the red brick temple through the F065 wall. It is also positioned in the alignment of the F015 wall to form a sort of rectangular enclosure (12.77 x 16.25 m or 208 m²) attached to the corridor of the red brick temple, within which is the US10 destruction layer, which contained the significant concentration of faience material and gold leaves.

Under the temple, previous occupation is confirmed by the presence of four mudbrick walls, F041, 18, 19 and 31, which form a rectangular space (2.94 x 1.51 m) cut to the west by the wall F003. A second rectangular space (2.95 x 1.88 m) is bounded on the east by the same walls and wall F026. The latter, a composite, results from the destruction and partial reuse during the construction of the red brick temple. The angle

10

Photo: © SFDAS/Musée du Louvre

Set of beads from the mudbrick chapel DAM21-A-008-005.

Faience box DAM20-A-010-003 (Winged Isis).

formed by the wall F026 and F031 corresponds to the north half of a Pylon, and its symmetrical southern counterpart is attached to a section of the wall in mudbricks on the edge, which certainly served as a support for a rectangular ferruginous sandstone threshold (80 x 60 cm). Therefore, we are in the presence of a double-chamber mudbrick chapel (3.88 x 7.02 m) with an entrance Pylon giving access from the east to west, the main axis of the chapel. Unfortunately, the two internal rooms of the chapel provide little information. The first easternmost room had a demolition level in mudbrick comprising ceramic older than that found in the fired brick temple (second half of the 1st Century bce). Below this level, a 60 cm virgin sand filling, devoid of any material except for a few beads, fills this space below the level of circulation of the chapel. The second western room of the chapel has a similar filling, also over 60 cm up to its foundation.

Sector E

Located on the northern slope of the main hill of Damboya, building E was discovered and completely exposed in 2020 in order to obtain a comprehensive plan. On this occasion, a few ancillary structures were uncovered, including a probable second building approximately 3 m southwest of Building E, which appeared to be parallel to it. Up to date, six rooms — i.e. half of the building — have been excavated down to the construction level, while five test trenches have been opened inside and outside the building to observe its foundations, covering a total of 190 m2 Building E is rectangular and orientated along a north-west south-east axis. It is 21.10 m long and 16.20 m wide. The building was organised around a probable square courtyard or light-well in the centre (room E05), with a row of rooms on all sides, except to the north-west, where two rooms flanked the central space. The main entrance (F003) was located at the southern corner of the building, a ramp of almost 4 m long. Finally, the presence of a floor is very likely given the thickness of the foundation walls, which varied between 0.70 and 0.90 m. Only the foundation level of Building E was preserved, while the walls and floor levels have entirely disappeared. The foundations were better preserved in the south-west, where thirteen courses were still standing, and poorly maintained in the north-east, where only eight courses were left. As was observed in Sector A, the occupation of Sector E seems to be relatively limited in time, as the ceramic material is dated exclusively to the second half of the 1st Century ce and the beginning of the 2nd Century ce

No floor was found inside Building E, but the interior floor level was located at least at the height of the highest preserved level or even higher, as no specific fittings intended to support a threshold were observed. The external ground level at the time of the building’s construction is known, with an average altitude of 359.79 m. This significant difference in height between the interior and exterior floor levels and the absence of floor surface inside the edifice means that the material found within does not correspond to a destruction layer, but to a filling intended to serve as a platform to raise the floor level inside the structure. Therefore, the excavated levels are those of foundation spaces (casemates) that were later covered by the various circulation floors of the building, which have now vanished.

Although the excavations of Building E and its surroundings

11 EGYPTIAN ARCHAEOLOGY ISSUE NO 59 AUTUMN 2021

General plan of Sector E.

THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE OF DAMBOYA

have not yet been completed, several remarks can already be made. First of all, the structure was raised by a podium. The casemates were filled with a large number of architectural pieces: column drum fragments, large bricks, torus-shaped bricks, as well as numerous fragments of painted plaster. These pieces and the presence of half column drums reused in the foundation indicate that Building E was built partly with the remains of an earlier building, already dismantled at the time of the construction. Production waste was also used to fill in the casemates since numerous remains of plaster were found mixed with the building materials. At least three walls contiguous to the building converged towards the main hill of the site and confirm the association of Sector E with the cult and economic complex identified in Sector A, of which it was contemporary.

Conclusion

A temple and its associated complex on the south plus a de luxe house founded on casemates on the north, obviously shows that the main hill of Damboya, which remains to be excavated, is of paramount importance for the understanding of the site — a royal city located at the very core of the Meroitic Empire. Considering the homogeneity of the dating, both coming from ceramic studies and C14 analysis, Damboya presents an urban site that fits perfectly with other surrounding sites of the same period: Naga, Wad ben Naga, Muweis, el-Hassa, and Hamadab. Such a promising excavation will undoubtedly help better our understanding of the urban network of the Shendi reach, at the heart of one of the oldest political structures in sub-Saharan Africa.

• Dr Marc Maillot received his PhD from Sorbonne University in 2013, and is now an associate member of the UMR 8167 “Orient et Méditerranée” (French National Research Center-CNRS). He is also Courtesy Assistant Professor at the University of Central Florida since 2015 and the French Archaeological Unit director (SFDAS) in Khartoum since 2019. Dr Maillot would like to thank the SFDAS archaeological team and the NCAM inspector Magdi Mohamed Ahmed, for the tremendous work performed at Damboya. SFDAS also thanks the people from the Damboya village for their help and Hamed Mohamed Bella, the guardian of the site, for his constant support and advice.

12

Above: General view of the western complex.

Left: General view of Sector E.

Photo: © SFDAS/Musée du Louvre

Photo: © SFDAS/Musée du Louvre

Mastaba Tombs at Tell Tebilla

Recent fieldwork at the ‘Beautiful Mouth’

Tell Tebilla was an important site in antiquity due to its thriving trade network. In 2018, a joint Egyptian mission from Mansoura University and the Daqahlia Inspectorate of Antiquities excavated at east corner of the site, Ayman Wahby tells us more.

Tell Tebilla (Ra-“sh”–Nefer) was a vibrant city in the eastern Delta during the 1st Millennium bce . Its history began in the Old Kingdom (c. 2686–2160 bce) when it functioned as a seaport, connecting with Mendes (Tell El Rub’a) through the Mendesian branch of the Nile for approximately 12 km. Artefacts of the site, such as pottery, amphorae, and black glazed pottery found near the water filtration plant, suggest continuous occupation from the First Intermediate Period to the Graeco-Roman Period (c. 2160 bce –395 ce).

Tell Tebilla is now approximately 25 hectares in size and the mound at its highest rises to 12 m above sea level. Over the years, it has been excavated by several teams. The first attempt to examine and study the site was in 1908 by Mohamed Shabaan, an Inspector of the site. This was after the Site Guardian informed him that the village inhabitants had found a sarcophagus. In 1980, an Egyptian mission excavated the site, and from 1999 to 2003 a

joint Egyptian-Canadian mission led by Gregory Mumford uncovered most of the area, with the Canadian mission returning in 2009. When the Inspectorate of Daqahlia, Ministry of Antiquities, worked at the site from 2012 to 2014, they discovered an intact tomb from the Saite Period (c. 664–525 bce).

The Ancient Egyptian name for Tell Tebilla was Ra-Nefer, meaning ‘Beautiful Mouth’, which refers to its location north of the entrance of Lake Manzala. The geographical location of this city enabled access to the Mediterranean Sea, so its inhabitants could exchange goods and products with neighbouring sea islands and the Levant. This trade network provided vast wealth to the city, making it one of the last prosperous cities of the Delta in the 1st millennium bce. Its modern name, Tell Tebilla, may be derived from Débéleh, meaning ‘ring’ in Arabic — the name given to the site by the French expedition to Egypt led by Napoleon in 1800. Napoleon’s team noticed that finger

13 EGYPTIAN ARCHAEOLOGY ISSUE NO 59 AUTUMN 2021

The excavated area of Tell Tebilla in the 2018 season.

© Mansoura University

rings were found in some tombs in the area, so they proceeded to name the site after the public name at the time. The city is also known as Balala and Billa, the latter used in the EES’ Delta Survey Project.

The entire Tell is now private property after having been reclaimed by modern houses to the northeast, agricultural activities to the north and south, and a water filtration plant to the west, which is located on top of an ancient temple.

The temple was built for the local god OsirisKhes(a) during the 22 nd Dynasty by King Sheshonq I (945–924 bce). He intended to make this site the main cult centre for Osiris. However, during the Persian invasion, the temple and city were destroyed, and the area then quarried for materials in the GraecoRoman Period (332 bce –395 ce). Remains of granite stones scattered across the site suggest a huge chapel or naos similar to the temple dedicated to Banebdjedet in Tell el-Rub’a (Mendes), which dates to the Saite Period (664–525 bce).

Newly discovered mastaba tombs

The season ran from 11th November to 25th December 2018 at the south-east corner of the Tell in an area of about 2,450 m2 . Initially, a topographical map of the site was produced from a magnetometer survey of 13 squares, each measuring 40 x 40 m. This led to the discovery of two structures, which were separated by a pottery-filled street and adjacent to an open court in the south. Further excavation revealed these structures to be two mastaba tombs, then named Mastaba 1 and 2. These mastabas date from the end of the Late Period to the Early Ptolemaic Period (c. 664–300 bce) according to their architectural form and pottery remains, including amphorae and Greek glazed decorated pottery.

Mastaba 1 is a mudbrick building measuring 13.5 m wide and 14.7 m long and divided into two rooms. The first room housed five burials containing six skeletons, of which four were male and two female. These burials may

represent a middle-class family, since no elaborate objects were found with them and the technique of mummification reflects the lower status of those persons.

Similarly, Mastaba 2 was divided into two parts, but the mudbrick building was shorter at 13.9 m wide by 12.8 m long. The western side consists of an open court, while the eastern side contained two empty rooms. To the south of these rooms, a rectangular cut measuring around 2.80 m by 1.50 m led to a vaulted underground sealed tomb situated 2 m below the surface level of the mastaba tombs. This tomb will be analysed further next season, along with the rest of the eastern section, which remains mostly unexcavated.

To the south of Mastaba 2, an open court slopes to the south in the south-east part of our excavation site. The court could have been used as a reception hall for public use, as there are no buildings in this area, and it is situated between the two mastabas. At the eastern corner of this court, a small pit measuring around 1 m x 50 cm and about 40cm deep, was filled with pottery as well as some amulets.

Overview of finds

Overall, 125 objects were registered in the Mansoura Storage Magazine and 68 objects in the Study Register of the Storage Magazine. These include two well preserved ‘Bes Jars’,

14

Grades of the Magnetometer survey completed in season 2018 at Tell Tebilla.

Right: The Vaulted Tomb found under Mastaba 2.

Right: A Topographic Map of Tell Tebilla. © Mansoura University

© Mansoura University

which were discovered in the pottery pit near Mastaba 2. Bes was the popular god of childbirth, music, and joy, and he is often depicted upon vessels such as these. Pots of various shapes and functions were catalogued on-site, including elongated, round bases, long necks and handles. One vessel was fascinating, as it had a hole in the base possibly used to pour water for purification. Many small pottery finds may have been used as domestic items, such as bread moulds, jars and perfume bottles. Decorated, black-glazed, Greek-style plates and an amphora handle with a Greek stamp represent the cities’ cultural influences from its trade network with the Mediterranean.

Numerous amulets representing different gods and goddesses, especially those connected with the worship of Osiris, Lord of Tell Tebilla. Amulets included Bastet, Horus, Min, Taweret, Sobek, Ptah, Isis, Thoth, Bes, Hathor, Mai Hesa, the wadj pillar, and the wedjat eyes, all made of faience. A smaller number were made of bronze, such as Harpocrates, Osiris and the head of Hathor.

Complete and partial terracotta statuettes were found during the excavations, including depictions of women and animals, such as horses. Some sculptures of note include a female head wearing a headdress typically seen on Greek goddesses and a male head wearing a cap, painted white, which could portray a soldier. Another male head made of faience represents Ptah-Patek, which dates to the 4th –3rd Century bce. Another figurine represents a bed with a man lying on top of a woman performing marital relations – a traditional pose from the Graeco-Roman era.

Conclusion

This joint mission at Tell Tebilla aims to shed more light on the importance of the site, in particular its religious and economic role during the Late Period in the First Millennium bce The excavations revealed two rectangular mastabas, which preserved many objects such as pottery pots, dishes, plates, imported amphorae, amulets, and six burials.

Future excavations will continue to explore the significant role and importance of Tebilla as a cult centre of Osiris, parallel to Mendes — the cult centre of Re. Additionally, the city’s role as a trade centre for Egypt’s neighbours during the Late Period will be examined further.

15 EGYPTIAN ARCHAEOLOGY ISSUE NO 59 AUTUMN 2021

• Ayman Wahby is a Professor of Egyptology at Mansoura University. He is Field Director of the Tell Tebilla Project, funded by Mansoura University’s Research Fund. This work was completed in collaboration with Maha el Seguni, Randa Baligh, Mosad Salama, Hosni Gazala, Mohamed Abedel Mawla, Ibrahim Seada, Sara El Emari, Rabab AbdelHakim, Shadi Omar, Ibrahim El Qasaby, Mohamed Gad, Zienab Dwiedar, Minas Abdo, Aya Habashi, Dalia Essam, Hamdi Abdel Azim,

A hole in a pot to pour water for purification.

A Bes Jar found at Tell Tebilla. An amphora handle with a Greek stamp.

Terracotta female with Greek-style headdress.

@BAR_Publishing barpublishing To sign up for our monthly newsletter, visit www.barpublishing.com 2021 | 9781407358109 | £46.00 £34.50 A River in ‘Drought’? JOHN W. BURN 2021 | 9781407358000 | £170.00 £127.50 Kom Tuman II SABINE A. LAEMMEL Archaeological Research

its

EES members receive 25% off all BAR Publishing titles. Use promo code EES25 at checkout. 25% DISCOUNT www.barpublishing.com QUOTE REF. EES25

Terracotta woman and man lying on a bed. Over 3600 titles in print with most available in our Digital Collection for libraries.

at

Best

MASTABA TOMBS AT TELL TEBILLA

Egyptian amulets of the crocodile god Sobek.

Resurrection in Panopolis

Graeco-Roman Period at the El-Salamuni Necropolis

Wahid Omran, Ashraf Okasha and Abdallah Abu-Gebel examine the blended cultural elements seen at the necropolis of Akhmim, which provide broader insights into Graeco-Roman Period funerary customs.

By the Graeco-Roman Period (c. 332 bce–395 ce), the ancient city of Akhmim was named Panopolis, meaning “city of the god Pan”. The Greeks assimilated Pan with the fertility god Min, the main deity of the city. The city played

a distinct historical and cultural role in Egypt during the Graeco-Roman era. It was the capital of the Panopolite Nome, the 9 th Nome of Upper Egypt, and continued as a thriving Hellenized metropolis. Greeks and Romans lived alongside the indigenous Egyptian population, and thus, it became a centre of both traditional Egyptian and classical Greek culture. By the 3 rd Century bce , Panopolis possessed several Greek civic buildings. Therefore, it was already heavily Hellenized when Septimius Severus finally granted the metropolis a city council (boul ē) in 201 ce , through which Panopolis became a Greek polis with its inhabitants converting to elite Greek citizens. Furthermore, the Panhellenic festivals were an essential part of civic life from the 3rd Century bce onwards. Since the Roman Period, its famous linen textiles put Panopolis on the map.

El-Salamuni Mountain was the main necropolis of the Graeco-Roman Panopolis. It is located 6 km north-east of Akhmim and around 2 km north of the famous El-Hawawish Mountain. The archaeological mountain is named according to the nearby modern village

16

General view of the El-Salamuni Mountain.

Kuhlmann, ‘Akhmim Cemeteries’, SDAIK 11, p. 53.

Photo: Wahid Omran

‘El-Salamuni’, which lies south of the site, and Nagc el-Sawâma-Sharq village lies to the north. The large cemetery contains tombs dating from the Old Kingdom through the Roman Period (c. 2686 bce –395 ce), many of which have been systematically recorded as GraecoRoman. In addition, the El-Isawieh, or ancient El-Faruqiyya, canal lies at the foot of the mountain to service the cultivated lands of the villagers.

El-Salamuni Mountain extends about 2,200 m in length and 400 m in height. The Akhmim Inspectorate Office divided the mountain into eight terraces from the bottom to the top, named A through H. In the centre of the cemetery, the uppermost part of the mountain, is located the rock-cut temple ‘Grotto of Pan’ dedicated to the god Min-Pan, Repit/Triphis/ Aperet-Isis and the child-god Kolanthes/ Harendotes, the divine triad of Akhmim. Construction at the temple by Nakht-Min, the high priest of Min, occurred during the reign of King Ay (c. 1332 bce). It was then substantially refurbished and enlarged by Hormaacheru, the archiereus, the high priest of Min, during the reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphus (285 –246 bce). First, the sanctuary served as a cult space for the quarry workers, who venerated Min, asking him for help and protection. Later, it was utilised as a necropolis sanctuary throughout the Graeco-Roman Period (c. 332 bce

30 ce), then these small caves were used by the Christian Anachorites during the early Christian Period (c. 30 –325 ce).

Since the first half of the 18 th Century ce , the cemetery of El-Salamuni was well-known as a regular stopping point for European travellers and archaeologists, including Friedrich Von Bissing, Jean Clédat, Otto Neugebauer,

Richard Parker and Klaus Kuhlmann. Later, through two field excavations in 1996 and 1997, the Akhmim Inspectorate Office rediscovered some of the tombs previously recorded by those scholars. However, unfortunately, these tombs remained covered and hidden for an extended period after the 1990s excavations to avoid illicit looting in the mountain. Furthermore, the Inspectorate Office excavated new Roman tombs in the cemetery, preserving four astronomical zodiacs on their ceilings.

Architectural Layout

Pharaonic tombs of the Old Kingdom, New Kingdom and the Late Period occupy the upper rows of the mountain. There are hardly any tombs known from the mid-level of the mountain slope, so terraces D and E remain unrecorded. Similarly, no tombs have yet been excavated in the lowest terrace (A), nearest the villagers’ land. Furthermore, many landslide openings of tombs are recognisable throughout the mountain, especially in the lower terraces of A, B, and C. The Roman façade-tombs situated on the lowest terraces of the mountain are mainly concentrated within rows B, C and F. These Roman tombs are more elaborate in shape and seem to be of finer quality. The Akhmim Inspectorate Office recorded the majority of tombs on the north and south

17 EGYPTIAN ARCHAEOLOGY ISSUE NO 59 AUTUMN 2021

–

Photo: Wahid Omran

RESURRECTION IN PANOPOLIS

Model: M. Gamal Thabet, Akhmim Inspectorate

The rock-cut Temple of El-Salamuni Mountain.

3D Model of El-Salamuni Tomb C1.

sides of the mountain, and most are now closed by steel doors, except for Tombs B2, B6 and C6. These tombs are cut horizontally into the mountain rock with a west-east orientation and a low entrance façade. They consist of two rooms, one extending behind the other. Only Tomb C1 has two rooms off-axis with a south-west facade. Tomb B7 is unique as it features three rooms. Its antechamber and burial room are on the traditional west-east axis, while an unfinished side-room was later cut south of the first room. El-Salamuni Tomb F4 is also noteworthy as a one chamber-tomb. Ordinarily, the burial room is larger than the first room. These rooms often house two burial niches cut into the walls, except for Tomb F4 with just one and three in Tombs C1 and B7. The façade-tombs were divided into four chronological groups using their architectural features by Klaus Kuhlmann, dating from the 1st to the 3rd Century ce

Funerary Art

The walls of the El-Salamuni Roman tombs are frequently divided into two friezes. The

uppermost shows Pharaonic funerary themes, while the lower ones always feature distinctive orthostates or opus sectile decorations– squared stone blocks or inlaid materials to create patterns. The latter, imitating Egyptian precious stones and signifies Roman influence, can also be found in Athribis. Bi-scriptural texts in hieroglyphs and demotic are widely recorded in the tombs, but no Greek texts have been recorded yet. This confirms the survival of indigenous Egyptian scripts among the local community of Akhmim until the Late Roman Period (c. 395 ce). Other features found in the tombs include horizontal or vertical pseudocolumns in black cursive hieroglyphs showing names of deities and black silhouette figures in the judgment scene.

In these tombs, deities appear in unique iconographic contexts, such as Tithoes, Bes, Ptah, and the local god Horudja/Haryotes. Osiris-Sokar is prominent in the tombs, as well as many other deities who are typically associated with mortuary contexts (Horus, Thoth, Anubis, Khepri, Isis, Hathor, Sekhmet, Neith, Maat, Geb, and Onuris), while others are typical for the region of Akhmim (Min-Re and Repit).

The El-Salamuni tombs are decorated with colourful Egyptian funerary iconography, showing a trend towards conservatism in mortuary practices. As a result, they record the survival of ancient Egyptian imagery of the afterlife until the late Roman Period, as late as the 4th Century ce. Despite the conservative character of funerary display in the El-Salamuni cemetery, the influence of Hellenistic art is also apparent in the tombs. The funerary art can be exclusively Egyptian or combine features of Egyptian, Greek and Roman repertoires. Moreover, the El-Salamuni tombs are recognised for the largest number of zodiac depictions in any Egyptian tombs, one of the

18

The black silhouette figures and the Ammit in the judgment scene, El-Salamuni Tomb C.

The Orthostates in El-Salamuni Tomb C3.

Photo: Wahid Omran

Photo: Wahid Omran

most prominent funerary characteristics of El-Salamuni. Both Egyptian and Greek syntax are depicted on the ceilings of the antechambers and the burial rooms. Perhaps immortality in Panopolis was thought to have been accessed through both Osiris as king of the underworld and through a cosmic approach to the celestial afterlife of Re. Moreover, it leads to the assumption that the Panopolitan Nome could have been a centre of the study of astral phenomena as zodiacs are also attested elsewhere in the region of Akhmim.

members throughout time, as the inhumation pits were added at a later date.

The El-Salamuni Mountain was the cemetery of the Hellenized population from Panopolis and its adjacent villages. The refined architectural layout and tomb paintings suggest that the cemetery was reserved for local elites and the urban Hellenized upper class. For example, high priests, landowners, high ranking local officials and veterans of the Roman army were buried there. The owners of the ElSalamuni tombs were likely wealthy and cultured; the deceased were often represented on a large, realistic, classical portrait, holding the rotulus (papyrus scroll), twig, or a laurel branch in his raised left hand, and a situla of Isis in his lowered right hand.

Burial Practices

In El-Salamuni, mummification remained standard practice. The mummified individuals were positioned in shallow, long niches within the burial chambers. These niches were painted with Egyptian scenes on their ceilings and walls, such as the winged vulture, hieroglyphic inscriptions, and the traditional Kheker decorations alongside crouching jackals. In a few cases, the niches show Hellenistic influences, such as a shelf for the deposition of the dead and imitate the Greek kline décor of the legs and mattress. Moreover, classical festoons, garlands, and the white-black geometrical veins are also attested. The niches were covered by a shell or baldachin. Furthermore, the El-Salamuni tombs often present a Greek burial style, shallow mummiform trenches in the antechamber floors. This likely suggests that the tombs were used for communal burials, possibly of family

El-Salamuni is still relatively intact and largely archaeologically unexplored. Very little data concerning the tombs has been scientifically and systematically published. An upcoming scientific publication will document the contextual information for the first time, and feature illustrations of the astronomical ceilings, from Akhmim’s GraecoRoman tombs. This will enrich knowledge about the funerary art and burial customs in Akhmim during the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods.

• Wahid Omran is a Postdoctorate Researcher at Lehrstuhl für Ägyptologie, Universität Würzburg, and Assistant Professor at Faculty of Tourism and Hotels- Fayoum University. Omran has worked at the site, with permission from the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities and Tourism, in 2015, 2017 and 2018 to document some of the Roman Tombs. His latest work in 2020 has focused upon the restoration of Tomb C1, which has been exposed since 1980. Ashraf Okasha is Chairman of the Sohag Inspectorate Office. Abdullah Abu-Gebel is the Director of the eastern Sohag Inspectorate Sector.

19 EGYPTIAN ARCHAEOLOGY ISSUE NO 59 AUTUMN 2021 RESURRECTION IN PANOPOLIS

Right: The classical portrait of the deceased holding the situla in El-Salamuni Tomb C1.

The burial niche in ElSalamuni Tomb F2.

Photo: Wahid Omran

Left: The south niche in the burial chamber, with painted winged vulture and lower Orthostates in El-Salamuni Tomb C3.

Photo: Wahid Omran

Photo: Wahid Omran

Kôm el-Khilgan: A 4,000 Year History

Kôm el-Khilgan was a significant cemetery site throughout history, with over 340 burials excavated to date. An overview of activity at the site, extending from the Predynastic Era to the Roman Period (early 4th Millennium bce to mid-3rd Century ce), is presented by Elsayed F.

Kôm el-Khilgan in the north-eastern Nile Delta is around 0.75 km south-east of elSamara village, 40 km from Mansoura (Daqahia governorate), and 20 km to the south of Mendes (Tell el-Rube) — the 16th Nome of Lower Egypt and capital of the 29 th Dynasty. The site is longer than it is wide, approximately 130 m north to south by 70 m east to west, with an area of roughly 8,600 m2 . For the most part, the site has a semi-level surface slightly higher than the surrounding landscape, except for a small mound of 290 m2 . This mound is located about 35 m to the west of the site, and its summit reaches a total altitude of 5.46 m, which is 2.28 m above the cultivated fields. The locals called the mound

tabet el-Sheikh

The site was identified in 1995 and registered in 2001 as one of the sites under the Antiquities Protection Act. The first excavation at the site

Eltalhawy.

was led by the Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale (IFAO) from 2002 to 2005, plus a season in 2006 dedicated to studying the results found during the excavation seasons at the site. To protect this small site surrounded by agriculture, because of its archaeological and historical importance, the supreme council of Antiquities decided to carry out excavation work at the site between 2018-2021. During these three years, the Egyptian mission has revealed important discoveries, representing various cultural phases.

The Roman Period (c. 30 bce –640 ce)

The latest ancient phase of occupation dates to the mid-3rd Century ce , when the site was used as a necropolis in the Roman Period. During the three Egyptian-led seasons, 36 graves dating to the Roman era have been found. 32 of these burials consist of rectangular pits running from west to east that cut through all the archaeological strata and part of the gezira or the natural layer untouched by human activity.

Inhumations were laid inside these pits on their back, with their heads oriented towards the west. Few burial goods have been discovered around these burials, only a gold earring and bronze coin dated to the mid-3rd Century ce were

20

Overview of the Second Intermediate Period occupations and Roman Period burials, (Squares O2, 3, 4 and P2, 3, 4).

found.

Several adolescent burials have been found on site; one individual was found inside an Egyptian-style amphora, dating to the mid-3rd Century ce. Other remains of an adolescent were situated in a pottery coffin. They were found with low sloped pottery edges, running from west to east. The subject was buried on the back with head to the west and the arms extended beside the body. The coffin lid was subsequently destroyed after the burial because it was too close to the surface of the site, which was previously exploited for farming.

Second Intermediate Period (c. 1650–1550 bce)

The next phase of the site dates to the Second Intermediate Period, more specifically during the 15th Dynasty under Hyksos rule (c. 1674–1535 bce). At this point, circular-shaped ovens constructed with mud bricks up to 80 cm in diameter, some kilns, several fire pits, silos and remains of mudbrick walls were discovered. Sinusoidal walls of mudbrick were also uncovered, possibly intended to protect the ovens and kilns from the wind. Many post holes have been found with vertical sides and a compact alluvial filling containing pot sherds, millstones, and remains of bauna, perhaps for religious purposes.

In total, 20 graves were excavated, orientated

were found northeast of the head, alongside an inscribed scarab.

A semi-rectangular pit, 2.75 m long and 1.40 m wide, with steep sides and a flat bottom, cut through all archaeological strata of the site to the gezira level. Two alabaster pots were laid beside a tomb constructed within this pit, which extended from east to west by 2.30 m and from north to south by 1.20 m and was built of mudbricks in a single course 0.20 m wide. Two skeletons were found in a poor condition on the natural surface. The first skeleton occupied the south side of the tomb and was possibly a woman buried on their left side, the head to the east, facing south. The upper limbs are flexed on the abdomen, while the lower limbs are flexed with feet joined. Three scarabs were found beside the skull, one of amethyst with a gold frame and an agate stone band. The second skeleton is the later of the two, buried on the left side with the head to the east and the face to the south. The upper limbs are flexed in front of the face and the lower limbs are flexed. To the north of the skull, fragments of human bones were found that may represent the remains of a young child’s burial.

east to west with the head to the east. They were laid either on the left or right side or on the back in a stretched or flexed position. Some of these graves held numerous funerary objects, including Tell el-Yahudia Ware, a distinctive black ceramic vessel type of the period, as well as scarabs, some of which are inlaid with gold.

One of the tombs of this era was a mudbrick grave about 1.8 m long and 1.15 m wide set in the standard alignment. It housed a child aged 4-7 years, who was buried in a flexed position on the left side with the head to the east, facing south. A palette and pottery bowl

Another tomb was excavated, 3.65 m long by 2.10 m wide, with mudbrick walls 60 cm wide. Its floor was covered with a layer of matting, as some fibres were found decomposing on the east wall of the tomb. The remains of six badly preserved skeletons were found inside. There is little evidence of burial goods other than pottery, stone vessels and amulets, including

21 EGYPTIAN ARCHAEOLOGY ISSUE NO 59 AUTUMN 2021

Overview of the Second Intermediate Period occupations and Buto Culture burials, (Squares G1 and G2).

Left: Amethyst scarab with a gold frame found in a Second Intermediate Period burial.

Second Intermediate Period burial KEK2018 GR.1.

KÔM EL-KHILGAN: A 4,000 YEAR HISTORY

Naqada IIIC Period (c. 3200–3000 bce)

The site was also an active cemetery during Naqada IIIC, indicated by the 15 tombs uncovered from this period. These burials included funerary goods, such as cylindrical jars and five slate palettes for grinding kohl (ancient eye cosmetic), one in the form of a tilapia fish. Some burials contained rectangular pottery coffins with tall sides, and clay blocks often supported the grave pits.

One burial consists of a semi-oval pit cutting in the gezira, the cut runs 1.58 m long and 1 m wide and its inner sides were covered with clay. Inside the cavity was found a rectangular pottery coffin, its dimensions 1.05 m × 0.57 m × 0.36 m and 0.04 m thick. A male skeleton, approximately 35 years old, was positioned in a foetal position on his left side, with the head to the south and face to the west. Three pots were laid on the north side of the coffin.

Another notable burial was found in a semioval pit cutting into the gezira, the pit running 1.70 m long and 1.15 m wide, the inner sides once again covered with clay. It was likely that this pit had been covered with mud and matting that had collapsed, leaving traces on the pit and coffin edges. The pit held a pottery coffin with the bottom of the coffin edges pierced with numerous small holes, possibly to dispose of liquids after burial. Its dimensions are 1 m × 0.57 m × 0.36 m and 0.03 m thick. The corners had larger holes located part way up the coffin walls, perhaps used for carrying and transporting the coffin from the place of manufacture. Inside the coffin was a female skeleton, approximately 25-35 years old, in a foetal position on her left side with the head to the south and face to the west. The upper

limbs are flexed and the left hand placed under the head with the right hand in front of the face. Two palettes had been placed in front of the face; one is rectangular and one spherical, the latter was found on top of a piece of flint. Six cylindrical pottery cups were also found: three in the north side of the coffin; two in the north-east and north-west, and the last cup on the middle north side. The three other cups were laid on the southern side; one is in the south-east corner, the second in the southwest corner, and the third to the east of the previous pot. On the outside the coffin, a pear-shaped vessel with a pottery lid was discovered to the south, as well as a smaller pear-shaped vessel to the west of this, with a further little pear-shaped vessel with a plate to the east, and to the east of the plate lay another little pear-shaped vessel.

Buto Culture (c. 4000–3500 bce)

The oldest phase of the site’s history dates to the first half of the 4th Millennium bce in Prehistoric Egypt. Overall, 270 graves have been excavated from this era known as the Lower Egyptian, Maadi or Buto culture. All graves were oval pits cutting the gezira. They were refilled after burial with sand, making it challenging to recognise the burial cut boundaries when they were excavated. This may also be the reason for discovering several later grave pits intersecting earlier examples of the same period. The skeletons were laid inside the pits in a foetal position, most on their left side orientated west to east with the face to the north, except for a few cases where some were laid on the right side and a few cases were positioned north to south facing west.

The graves of this phase were characterised

22

scarabs.

Left: Naqada IIIC Period Grave KEK2020 GR.P.S.1.

Right: Naqada IIIC Period Grave KEK2020 GR.P.S.2.

Predynastic Palette in the form of a tilapia fish found in a Naqada IIIC Period burial at Kôm el-Khilgan.

by little or no funerary goods. Only one or two small handmade lemon-shaped ceramic pots were found, often laid near the body, generally at the head, feet or when the grave was closed at a higher level. One or two shells were also discovered, probably used for grinding kohl, which suggests the importance of eye makeup even in this early age of ancient Egyptian civilisation. A thorough study of all skeletons of this period reveals 33 females, 53 males, and 23 unidentified genders. The average age of these burials is between 22–35 years old, a relatively young age with 17 children under the age of six, and 18 burials between 12–17 years. Dental diseases are apparent in many cases, mainly caused by malnutrition, as well as two people with broken leg bones.

In conclusion, the archaeological stratigraphy and phases of human occupation indicate that the site has been extensively exploited as a cemetery during the first half of the 4th Millennium bce and no items of daily life have been found dating to this period. The site was also used during the Naqada III Period as a cemetery, but it is significantly smaller and no evidence for daily life was found for that period either. The site seems to have been abandoned from the Old to Middle Kingdom (c. 2686–1650 bce). Yet, the area was again exploited during the Second Intermediate Period (c. 1650–1550 bce), either as a

settlement or a cemetery. A further phase of desertion can be identified before returning to intense use during the Roman Period (3rd Century ce).

23 EGYPTIAN ARCHAEOLOGY ISSUE NO 59 AUTUMN 2021

• Elsayed F. Eltalhawy is the Director General of Antiquities in Dakahlia and Supervisor of Antiquities in Damietta Governorate for the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities. He extends his sincere thanks and appreciation to the team of the Kôm Al Khalij Excavations Mission: Mohammed A. Ebd Elaziem, Maali M. Hashesh, Maher A. Abu Alesaad and Asmaa E. Elsayed.

Buto Culture burial KEK20–21 SQ.15 F.1929.

Buto Culture burial KEK20–21 SQ.15 F.1923–22.

Digging Diary 2021

Summaries of archaeological work undertaken in Egypt and Sudan since spring 2021. Sites are arranged geographically from north to south. Field directors who would like reports of their work to appear in EA are asked to email the editor at ea@ees.ac.uk.

LOWER EGYPT

Plinthine: At Plinthine/Kôm El Nugus, excavation of sector 6, a Saite Period wine factory, and sector 10, a Ptolemaic Period villa dedicated to the production of wine were completed in 2021, and their entire layout is now documented. They illustrate the dynamism of the wine production at Plinthine during Antiquity. Several major finds were made in sector 7, at the center of the kôm, including the south-western corner of a building identified with a temple was discovered (building 1), most probably dated to the Ptolemaic Period. It was constructed with reused Pharaonic blocks, including several bearing the name of Ramesses II. Furthermore, two mud-brick buildings were found, dated to the Third Intermediate Period, lining a street, made up of levels of silt, ashes and small limestone rubble. Nearby, the southeast corner of a second massive building made of local limestone which seems, like building 1, to be Hellenistic. Finally, a new sector (#11) was opened atop of the western levee of the kôm. It yielded several phases of construction, the most ancient one being a multi-room building topped with vaults, probably dated to the Saite Period, the period during which the settlement’s vitality seems to be at its peak.

Taposiris: At Taposiris, the operations were entirely devoted to the study of the lake harbour. Three sectors were investigated: two warehouses on the south artificial levee (sector 2); the so-called “platform building” and its surroundings

(sector 20) in the area of the bridge; on the north quay, a building located on a high mound (sector 21). The “platform building” was built after the mid-7th Century ce and might have been a sort of harbour master’s office, as previously suggested by Thiersch in 1902. The two warehouses were essentially oriented towards the redistribution of wine production from the southern shore of the lake considering the number of wine amphorae (LRA 5/6 and AE 8 types) found there. Already well attested in the northern contexts of the city, these new discoveries confirm the still vivid role played by Taposiris in the Mareotis economy after the Arab and Muslim conquest, from the 7th Century until the early 8 th Century ce

A conservation mission was also conducted in the Ptolemaic baths of Taposiris, excavated by the mission between 2003 and 2011.

The above digs were led by Bérangère Redon (CNRS, HiSoMA) and brought together 15 researchers, 40 workers, and with the collaboration of five MoTA inspectors. Follow both of these sites on Twitter using @TapoPlinthine or https:// taposiris.hypotheses.org/

Wadi el-Jarf : The 11th campaign of the Wadi el-Jarf archaeological mission took place this spring from March to April, comprising a small international team led by Pierre Tallet (Sorbonne University/IFAO) and Egyptian team of 37 workers from Luxor (Gurna) led by Reïs Gamal Nasr al-Din. The work was two-fold: excavation of the 2nd group of storage galleries continued and

study of the camps situated on the Red Sea Shore was completed.

A group of 12 storage galleries, were cut on the edge of a wadi. Galleries nos 28, 26 and 24 were completely excavated this year, while excavation of galleries 25 and 27 just began. They were mostly used to store big storage jars, most of them inscribed with the names of the royal teams that were producing and using them on the site.

At the same time, the study of a huge deposit of anchors left between two stone buildings near the sea-shore at the end of Khufu’s reign was completed this season. They weighed a total of 21 tons with an average weight of 200 kg. Inscriptions on the anchors name the four boats that were used at that time. Dozens of fragments of sealings were also found, some of them still bearing imprints of cylinder seals showing sometimes the Horus name or cartouche of Khufu, as well a small accounting inscription.

https://amers.hypotheses.org

UPPER EGYPT

Tell el-Amarna : The 2020 autumn season was devoted to recording finds from the Great Aten Temple stored in the site magazines, work at which resumed in the spring of 2021. The cleaning and recording of the remainder of the foundation trench of the north wall of the temple was finished, as was the laying of the final length of a stone foundation which will support a course of fine Tura blocks at ground level. Additional areas of the original gypsum-concrete foundation layer alongside the wall were also exposed,

24

Plinthine: Two Ptolemaic(?) buildings and a Third Intermediate Period street. Photo: MFTMP.

Taposiris: The façade of the Ptolemaic baths of Taposiris after the conservation mission. Photo: MFTMP.

Amarna: Reconstructed stonework at the Great Aten Temple’s north-east corner. Photo: Amarna Project.

revealing that much of it has survived in a fairly good condition. Many more fragments of carved stone were recovered from earlier excavation dumps, amongst them architectural pieces in granite. For much of the time photography of the stone pieces from the temple was continued.

From December to March, a 962 m long stone wall was built at the north end of Amarna, to help protect the Desert Altars and the North City from the illegal encroachment of agricultural land. The Amarna Project is led by Barry Kemp and Anna Stevens.

www.amarnaproject.com

Coptos: In spring 2021, the reconstruction of the statue pedestal dedicated by the Adenite Hermeros in 70 ce was completed by repositioning the corniche. The bases of the two adjacent pillars were also re-erected and a modern brick back wall was built to restore visually the ancient setting of the statue in the Roman colonnade surrounding the temple of Min and Isis.

In the mammisi area, the new excavations to the east and west of the naos floor uncovered more foundation stones flanking the sanctuary, confirming the hypothesis of a tripartite plan.

To the south, remains of a Late Roman workshop were exposed, probably connected with the unidentified features found further north in 2012

2013. The craftsmanship activity carried out there used much water, as shown by a sloping mudbrick structure connected with a sloping channel flowing from it into a rectangular basin. On the eastern edge of the excavation, the finely plastered wall of the 2nd Pylon (Roman) was found and cleaned to its foundation level.

In the course of the work, about 275 new fragments from the mammisi scenes, mainly Roman, were collected.

https://www.ifao.egnet.net/ recherche/archeologie/coptos/

Medamoud : Medamoud was surrounded by a city that had never been explored

until recently. Since 2015, the IFAO mission has aimed to study these urban sectors and understand the craft productions that they housed. Recent excavations have confirmed that Medamoud was one of the great ceramic manufacturing centres in operation between the New Kingdom and the Ptolemaic Period. So far, five workshop areas have been uncovered with several well-preserved ceramic kilns.

Between 2019 and 2021, the excavation focused on a 32 × 10 m trench, uncovering two workshops dating to the 9 th and 8 th Centuries bce . The first preserved two kilns with several stone lined pits and three chambers; the second, to the south, housed three more kilns. One of them, has imposing dimensions: 3.35 m external diameter and 2.30 m internal diameter, with a minimum depth of 2.70 m. Further west, a new area of kilns dating to the mid-18 th Dynasty was also excavated in 2021. Its upper level (laboratory) measures 1.60 m of elevation, one of the largest examples discovered in Egypt.

https://www.ifao.egnet.net/archeologie/ medamoud/

Karnak : The chapel of Osiris-Ptah Nebankh (Lord of Life) lies south of the 10 th Pylon of the Amun-Re precinct, and east of the ram-headed avenue of sphinxes that runs from the 10 th Pylon to the Mut precinct. It is one of a series of Osirian chapels built by the 25th Dynasty Kushite kings Taharqo and Tantamani, who are represented in the chapel scenes alongside various gods and goddesses.

During the 2021 season led by Essam Nagy, the project’s main target was to conserve and restore the chapel — 100 years after its first restoration. The chapel was in a poor condition, its wooden ceiling badly damaged.

The chapel is in a rather unexpected place, just outside of the 10 th Pylon and slightly off that same axis to the east. Consequently, the team focused on the relationship of the chapel to the other surrounding architectural

elements, producing maps for the area.

Previous seasons revealed two structures to the east of the chapel, so this season aimed to fully excavated them to establish whether they are houses, administrative, cultic, or domestic buildings. The work also focused on pottery analysis to ascertain the date and the function of the site.

https://osirisptahnebankh.org/

SUDAN

Old Dongola : The Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology, University of Warsaw (PCMA UW) team led by Artur Obłuski and Dorota Dzierzbicka continued to excavate the Funj Period urban settlement (16th –18 th Century ce) on the citadel hill. In the central part of the citadel, domestic compounds were found to stand on top of earlier buildings, including a very large medieval structure. A huge apse (6 m in diameter) with remains of painted plaster helped identify this building as a church of unprecedented size. A test trench was excavated in the apse to investigate the depth of the Funj Period strata. The floor of the church was reached through a borehole drilled in the trench. Plaster fragmentarily preserved on the apse wall bears paintings with figures of saints. Directly to the southeast, a large dome of fired brick was discovered. Given its location inside the settlement, it may be a tomb of someone from the highest elites of the kingdom.

In the “House of the Mekk (Funj Period king)”, excavation of a partly covered courtyard revealed wall graffiti depicting animals (most likely horses) and domed buildings. Collaborative archaeology activities were also continued. The main tangible output of the project is heritage and sustainable development strategy as well as commitment to implement it made by stakeholders from the Sudanese government, international bodies (UNESCO, EU), and Polish expedition to local communities.

https://pcma.uw.edu.pl/ en/2019/04/02/dongola-2/

25 EGYPTIAN ARCHAEOLOGY ISSUE NO 59 AUTUMN 2021

–

Coptos: The statue base and pillars, with restoration team. Photo: IFAO-Museo Egizio, Torino Mission.

Karnak: Egyptian team working at the chapel of OsirisPtah Neb-ankh (Lord of Life) Photo: OPNARP.

DIGGING DIARY 2021

Old Dongola: Drone photography over the site of Old Dongola in Sudan. Photo: PCMA UW.

From in situ to the Grand Egyptian Museum

Tracing the archive of William Matthew Flinders Petrie

Tanis was an important Egyptian city located in the north-eastern Nile Delta. Many objects originally discovered there have since been transported to museums, including the Grand Egyptian Museum (GEM), which will be opening soon. Ahmed Nakshara highlights the significance of archival photographs for tracing the provenance of these museum objects.

In his 1904 book Methods and Aims in Archaeology, Petrie wrote, “Photographs are essential for all objects of artistic interest, and for expressing rounded forms for which elaborate shading would otherwise be needed” (p. 73). However, Petrie’s perspective on the use of photography in archaeology had been formed much earlier, possibly influenced by Pitt Rivers. It was during his second season (1881–1882) of surveying the Pyramids of Giza when Petrie took his first archaeological photographs. Since then, photography continued to be an integral tool in his excavations. To such an extent that he worthily deserves the title The Father of Egyptian Archaeological Photography, as Patricia Spencer explored in the Summer 2012 EES Newsletter (p. 4–5).

As the second delegate of the newly formed Egypt Exploration Fund (later Society) to explore the Nile Delta, Petrie arrived at Tanis on 4th February 1884. His intended plan was “to see every side of every block here, copy every piece of inscription, photograph everything worth having, & make a plan shewing the place of every inscribed block”, as he wrote in his journal (Petrie MSS 1.3, p. 107 on 14th March 1884). However, there had

been a delay with the transport of sheets of iron for the roof of his house, holding up his plan. He wrote a few weeks earlier: “I cannot begin photographing properly here until I have a room to get chemicals & things out, for I am crammed here in one room; and I must have a dust tight roof before gelatine plates can be left about.” (Petrie MSS 1.3, p. 91 on 22 nd February 1884).

Once set up appropriately, Petrie developed his photographs in his house and regularly sent them to England, where Amelia Edwards would use them in publications. “…I enclose 31 photographs, & hope soon to send more; these I have just done yesterday & today in time for the mail. Miss Edwards had better have them, after being fixed…” (EES.COR.016.f.24, on 22 nd March 1884). Moreover, he sent photographs of objects to Gaston Maspero in Cairo, who would then choose which artefacts he wanted to keep for the Bulak Museum. Although the glass plates were relatively heavy, Petrie carried his camera and equipment wherever he went outside Tanis to explore the nearby Tells. He also used some of these heavy plates to capture some of his workmen’s faces and to record some of the daily life of the villagers. “This afternoon I took the camera over to Sueilin, & I hope that I have got some groups on the way, camels, &c.” (Petrie MSS 1.3, p. 167 on 9 th May 1884).

Through Petrie’s homemade pin-hole camera lens, Tanis’ earliest and most complete

26

A section of a letter to Reginald Stuart Poole, which notes that “I enclose 31 photographs” for Amelia Edwards, signed by William Matthew Flinders Petrie (EES. COR.016.f.24 on 22nd March 1884). Courtesy of The Egypt Exploration Society.

photographic archive was captured during his long season at the site, lasting until 23rd June 1884. Petrie’s Tanis photographs are now kept at the Lucy Gura Archive at the EES office in London under the title “Tanis Series” (available online via Flickr under the heading Delta Series Negatives). It is worth mentioning that, although this series is named after Petrie’s first large-scale excavation site at Tanis, it contains all photographs of Petrie’s excavations in the Delta during the years 1883–1886. Through this photographic archive, the journey of some Tanitic objects that were rehoused recently at the GEM could be traced.

Development of the Grand Egyptian Museum

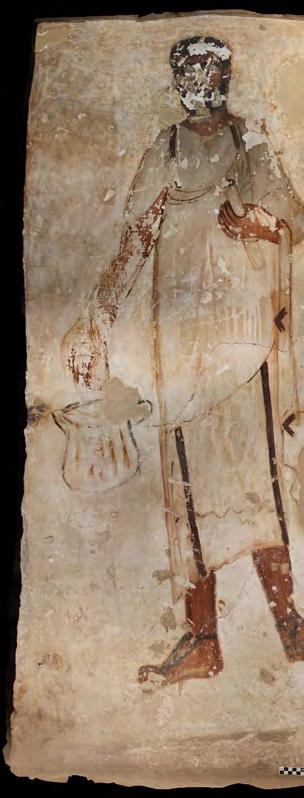

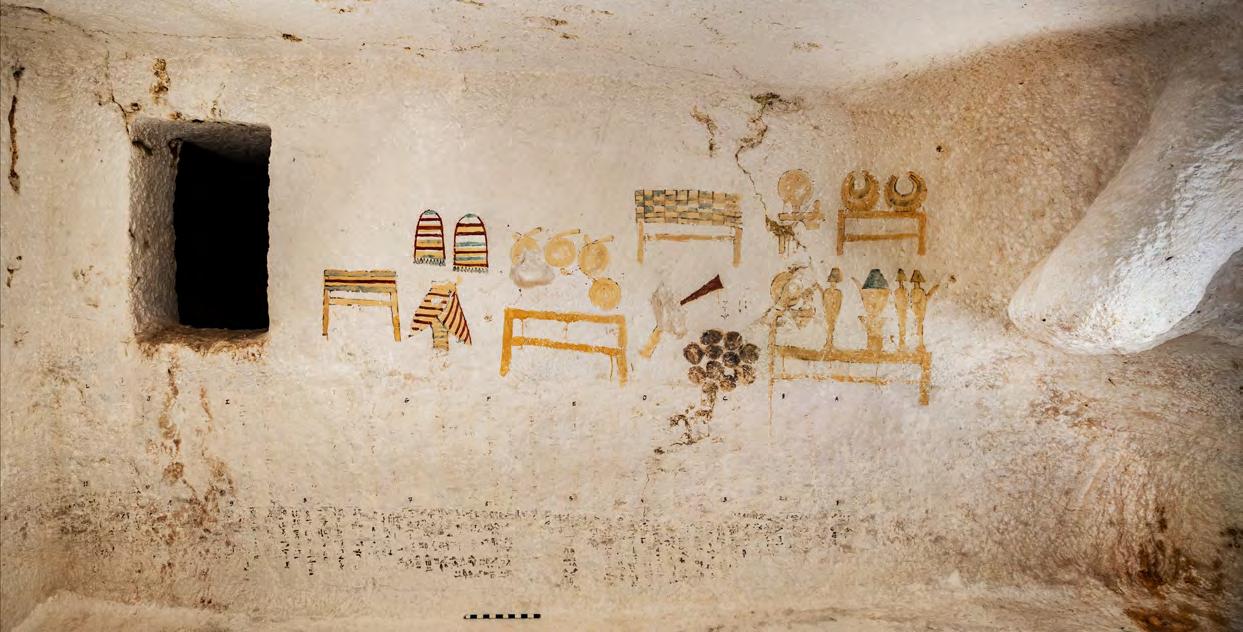

The Grand Egyptian Museum (GEM) is the world’s largest museum dedicated to one civilisation, holding the largest collection of Egyptian antiquities globally. It introduces its visitors to an enjoyable, entertaining, educational and cultural experience through a series of museum exhibitions, a children’s museum, a crafts centre, a conservation centre, theatres, cinemas, gardens, restaurants, shops, and more. In order to alleviate the overcrowded conditions of the Cairo Egyptian Museum (CEM), the Egyptian government announced in 1992 its intention to build a state-of-the-art complex of museums and associated facilities fit for the 3rd Millennium ce . On 7th January 2002, a global architectural competition to design the new museum was held under the auspices of UNESCO and the International Federation of Architects. The first prize was awarded to the architectural design by Róisín Heneghan and Shi-Fu Peng in July 2003. Meanwhile, on 4 th February 2002, the foundation stone of the museum was laid at