10 minute read

Rescuing the Mamluk minbars of Cairo

by TheEES

In 2018, the Egyptian Heritage Rescue Foundation (EHRF) launched a two-year project to document the minbars of the Mamluk period that can be found in many religious monuments in Egypt and museum collections worldwide. Omniya Abdel Barr describes the efforts to restore, conserve and protect these pulpits.

A minbar (pl. manabir) is a stepped pulpit located at the central point of a mosque to the right of the mihrab, the prayer niche directing to Makkah. It provides a raised structure for preachers to be better seen and heard at a distance during their sermons (khutba) before Friday and Eid prayers. However, pulpits were present in Egypt long before Islam. One example survives in the Coptic Museum and shows a raised seat with six steps – or seven if we count the seat – and two columns on both sides. This white limestone pulpit was made in the 6th century CE for the Monastery of Jeremiah. James E. Quibell, who excavated the pulpit in Saqqara in 1908, and K. A. C. Creswell both suggested that it could have served as a prototype for the Islamic minbar.

Advertisement

The minbar of the Mosque of Sultan al- Mu’ayyad Shaykh (built 1415–1421 CE).

EHRF

After the Prophet Muhammad built his mosque in Medina, he used to preach next to the trunk of a palm tree, which supported the roof. Later, he ordered a raised wooden seat with two steps to be made. It is believed that the carpenter who made this structure was Coptic or Byzantine, and so it is thinkable that the first minbar in Islam was influenced by the Egyptian pulpit. The Prophet used the minbar to deliver his sermons and to answer queries. During the first decades of the caliphate period, this minbar became a permanent reminder of the Prophet’s presence. It was the symbol of state power and religious authority. With the early Muslim conquests, more minbars were built in the new provinces and installed in every mosque. The design and form developed under the Umayyad dynasty (661–750 CE), and more steps were added. The grand structure also served to designate a special area for sultans and caliphs to pray. Today, these minbars have important spiritual and historic as well as artistic value.

The Mamluk minbars

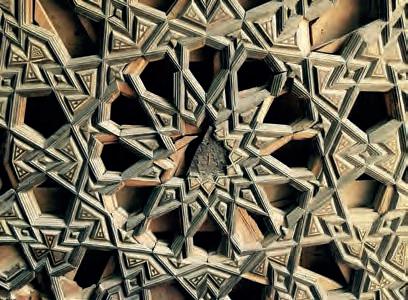

Cairo was the capital of the Mamluk sultanate (1250–1517), a period representing the golden age of medieval Egyptian art and architecture. The country regained its position as an international economic centre and secured links between east and west. The Mamluks were important art patrons and generously financed their religious and funerary complexes. The minbars in these foundation were mainly made from imported and local wood, with finely carved panels and inlaid with ebony, ivory and mother of pearl. A few examples were made from polychrome marble and stone. The design of the Mamluk minbars shows advanced use of geometry in decoration and highlights its development in Egypt.

The Mamluk minbars are appreciated for their fine craftsmanship. Almost every international collection on Islamic art acquired a piece: panels from the minbar of Sultan Lajin, made for the Mosque of Ibn Tulun in 1296, are today present in twelve museums and three private collections. An entire minbar made during the reign of Sultan Qaytbay (1468–1496) was purchased in 1867 by the Victoria and Albert Museum in London and has been on display ever since. It can be found in the Museum’s Jameel Gallery.

The minbar of Sultan Lajin, restored by the Comité de conservation des monuments de l’art arabe in 1913.

Richard Wilding

Minbar thefts, past and present

The uprising in January 2011 created a security void and attacks on heritage multiplied. Illicit digging took place on archaeological sites, museums and cultural institutions were damaged and historic buildings stripped of their precious architectural elements. While security improved again 2013, this did not put an end to the many acts of vandalism and looting that are still targeting Egypt’s heritage and cultural identity.

Detail from the minbar of al-Ghamri in the funerary khanqah of Sultan Barsbay. The doors were looted in 2007. The minbar of the Mosque of Sultan alMu’ayyad Shaykh (built 1415–1421 CE).

EHRF

Historic Cairo has been subject to neglect and vandalism before. Some significant thefts took place in 2007, 2008 and 2010. However, the number increased noticeably after 2011. Therefore, in 2012 we started documenting and identifying thefts from the monuments and historic buildings in the medieval centre (as registered on the World Heritage list in 1979). Most of these attacks were targeting minbars: a total of 13 were affected by partial or total losses. Usually, door leaves were first to disappear, whether from the entrance portal (bab al-muqadim) or the sides (bab alRawda). The minbar of the Mosque of Amir Qanibay al-Rammah (built 1503–04), overlooking the Citadel Square, disappeared entirely. It was obvious that the looters knew the value of what they were stealing and that were feeding a new demand emerging on the international art market.

But already in the mid-19th century the Mamluk minbars became subject to looting. Old photographs of the Cairo mosques show these structures stripped of their carved and inlaid panels. In an 1882 article for The Academy, Amelia Edwards mentioned how precious architectural elements in historical buildings, such as wooden ceilings, ceramic tiles and carved woodwork were pulled out, replaced and sold to tourists and bric-à-brac dealers. Islamic art collectors started acquiring these pieces found on sale in Cairo, which is how many private and museum collections were formed. After the establishment of the Comité de conservation des monuments de l’art arabe in December 1881, historic buildings were listed and systematically restored. The minbars were given great care and attention and only the best carpenters were hired to replace the missing parts. No further looting took place until recent decades.

As the latest thefts caused concern, we started checking catalogues and sales records of auction houses, focusing on the three prominent London auction houses of Sotheby’s, Christie’s and Bonhams that have dedicated departments of Islamic art. After assessing sales from 2000 to 2017, we found that a total of 52 carved wooden panels, possibly dating to the Mamluk period, had been sold. A noticeable surge in the sales appeared in 2008, with 15 lots, and in 2011, with seven. In every year except for 2006 at least one lot containing Mamluk wooden panels was offered

Side flank of the minbar in the funerary complex of Sultan al-Ashraf Qaytbay, looted in 2013.

EHRF

This demonstrates a steady demand for these artefacts on the art markets since 2000, their intricate design and expert craftsmanship appearing to be key selling points. The most expensive panel was sold at Christie’s in April 2000 for £531,750. All lots were attributed to the Mamluk period and only four were linked to architectural elements other than minbars. In some cases, catalogue descriptions attributed provenance to known private collections, suggesting that they were acquired before the 1970s and possibly as far back as the 19th century. However, most of the lots were not linked to a specific collection. As all three auction houses are reputable businesses known for their expertise and checks on their lots’ authenticity, the lack of provenance for these objects was worrying.

It highlighted the vulnerability of Mamluk heritage at risk from looters and collectors’ demand. Since the pieces in question could not be linked to their original minbar, it was impossible to stop thefts or sales. This is how the idea of the ‘Rescuing the Mamluk Minbars Project’ developed. We immediately decided to start a full architectural survey and create photo documentation of the minbars still in place in Egypt.

The project

Mechanical and chemical cleaning under way of the minbar of Amir Abd al-Ghani al-Fakhri.

EHRF

Mechanical and chemical cleaning under way of the minbar of Amir Abd al-Ghani al-Fakhri.

EHRF

The project prepared a complete record of 42 minbars in Cairo, one in Fayyum and one in Qus. For each minbar surveyed, a full set of architectural drawings was created along with a detailed photographic catalogue. All minbars were Mamluk except for one: the minbar of the Mosque of al-‘Amri in Qus, the military and administrative centre of Upper Egypt in medieval times. Built in 1155–56, during the Fatimid period, it is the earliest surviving example from Islamic Egypt. It was included in our survey because of its historical importance and artistic value, representing a masterpiece of Islamic woodwork.

Once the architectural drawings were complete, we undertook a condition survey of every minbar to assess its current state. Additional layers were applied to the minbar drawings to show dirt and dust, partial or total loss of elements, cracks and structural weaknesses, corrosion and discolourations as well as decay. This was essential to identify the necessary interventions for every minbar. In addition, a risk assessment was done, taking into consideration the minbar itself as well as its surroundings: the greatest risk after theft is fire, as nearly all these minbars are made of wood.

Fire can be caused by bad wiring, as all minbars are connected to audio systems for the delivery of the khutba. Other electric installations on or near the minbars include fans and lighting units. In most cases, wiring runs directly on the body of the structure, usually set up by the mosque keepers, who are hired by the Ministry of Awqaf (religious endowments). Fire hazards are further increased by the presence of rubbish and inadequate storage. Unfortunately, many mosque keepers lack awareness and appreciation of the value of the minbars and they are not usually concerned about their protection. Other risks are neglect and structural problems, including earthquakes: if the structure of a mosque is not properly maintained, a collapsing roof can easily destroy the minbar beneath.

The minbar of Ganim al-Bahlawan after having been looted in 2008.

Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities

Based on these studies, the project created a list of priorities. Mitigation actions were applied to 13 minbars, maintenance to 14. Four minbars were selected for full restoration, including the minbar of Ganim al-Bahlawan (built in 1478). It had been entirely looted on 28 May 2008. All its side panels had been removed as well as the entrance portal, leaving only the structure of both flanks, the staircase and the dome. Some of the stolen parts could be repatriated when, in 2014, Danish police intercepted a parcel destined for the USA that contained wooden pieces with inlaid panels taken from the Ganim al-Bahlawan minbar. Its restoration involved salvaging the structure still in situ and reuniting the repatriated pieces with it. However, the process made us aware of the tragic loss of know-how in traditional woodwork. Only a single master craftsman was available with the necessary skills to join the restoration team.

The database created by project is, we believe, the first of its kind in Egypt. It is not exclusive to the minbars and can be developed to accommodate material from other architectural elements, such as doors, epigraphic panels, window grilles, mosque lamps, and so forth. It pulls together all the material and information from the project’s different teams, making it now possible to create links between the data and to conduct more focussed research. This has allowed us to identify the origin of the panels found in an auction house in Paris in 2019, resulting in the cancellation of their sale.

Cement tiles with a geometrical design inspired by the Mamluk minbars. 28 May 2008.

EHRF

The project has trained early-career professionals, graduates in architecture, archaeology, conservation and art history. Many volunteers from Cairo and abroad have participated and received training in documentation and conservation to develop their technical skills. The project has delivered series of workshops to children and the general public. In addition, a group of junior architects joined a three-day seminar to study Mamluk geometry and apply this knowledge in their projects. Finally, the Egyptian Heritage Rescue Foundation (EHRF) partnered with 13 designers and craftsmen working in different fields from khiyamiyya (quilting) to tile making, interior design, jewellery and fashion. Each participant created a contemporary design inspired by the geometry and ornamentation of the Mamluk minbars.

Workshop with junior architects: drawing a sixteen-fold star.

EHRF

We hope that the legacy of the project will be to create sustained interest and appreciation both in Egypt and abroad. The EHRF will continue to care for the minbars alongside the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities. Our aim is to share the knowledge we have acquired through the project with wider circles of professionals as the best way to raise awareness and we hope that this can play a role in the protection of Egypt’s heritage.

Omniya Abdel Barr is a conservation architect working in Cairo and London. She is a project manager at the Egyptian Heritage Rescue Foundation and the Barakat Trust Fellow at the Victoria and Albert Museum working on the photographic archive of K. A. C. Creswell. The Rescuing the Mamluk Minbars Project was set up in partnership with the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities (Egypt) and is funded by the Cultural Protection Fund of the British Council in partnership with the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (UK).