12 minute read

The North Cliffs Cemetery at Amarna

by TheEES

Cover Photo: A view across the North Cliffs Cemetery from the approach up to the rock-cut North Tombs. The Amarna Project

Excavations at the cemeteries of Amarna are providing new perspectives on non-elite lives and burial practices, and on urban environments in ancient Egypt. Anna Stevens, Gretchen Dabbs, Amandine Mérat and Anna Garnett present recent work at the Amarna North Cliffs Cemetery to demonstrate how collaborate approaches are helping to extract social data from these simple pit-grave cemeteries.

Advertisement

The cemeteries of Amarna

The unexpected discovery in the early 2000s of four non-elite cemeteries at Amarna spurred a long-term collaborative research campaign that has now recorded over 800 interments across these four burial grounds. Outwardly, the cemeteries are very similar. Most of the deceased were wrapped in textile and matting, and buried in a simple pit grave; there is not a lot of variation from grave to grave. Yet each burial ground also has its own character, and one of the aims of the research is to tease out the differences between the cemeteries, and what these indicate of how Akhetaten functioned as a city, and was experienced by its ancient population.

The North Cliffs Cemetery

From 2005–17, fieldwork targeted two large burial grounds located in wadis beside the officials’ tombs: the South and North Tombs Cemeteries. These may have served, respectively, as the primary burial ground for the Main City, and for one or more labourers’ communities. Each contains several thousand burials. In 2018, excavations shifted to a smaller burial ground, the North Cliffs Cemetery, located on the low desert below the tomb of the priest Panehesy (North Tomb 6), with a follow-up season of post-excavation work in late 2019.

The North Cliffs Cemetery lies on the low desert near the North Tombs, visible in the cliffs in the background of the image.

The Amarna Project

The burials

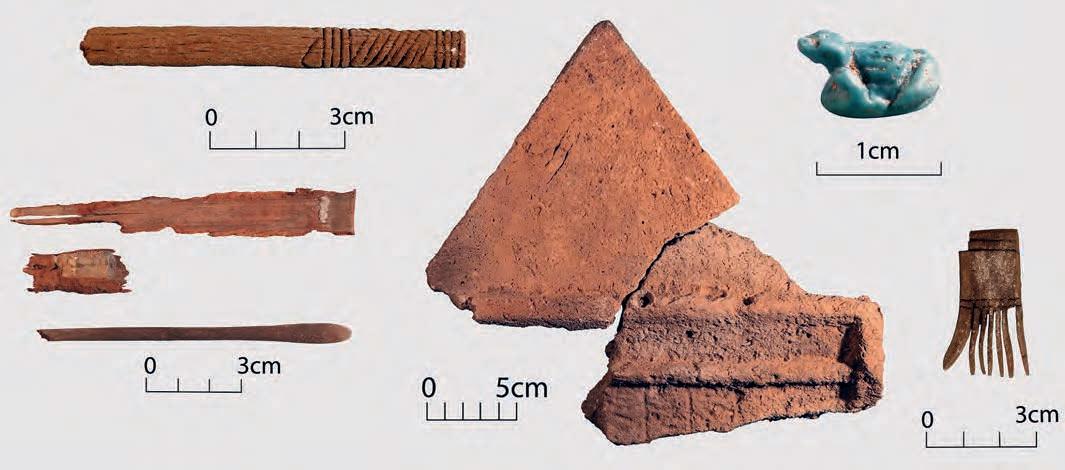

The North Cliffs Cemetery is a much smaller site, with around 900 to 1,400 interments. A sample of 72 probable graves was excavated, spread across the cemetery. In terms of approach to burial, the interments here are again very similar to those elsewhere at Amarna, and particularly the South Tombs Cemetery. Most excavated graves contained just one individual, for example, usually wrapped in textile and matting. Occasional fragments of wooden coffins were recovered, indicating that a few people had access to a more elaborate burial container. There were also pieces of at least four limestone stelae, lying disturbed on the surface of the cemetery, but presumably once used to mark graves. One stela preserved part of its upper edge, which was carved into a triangular form. This shape is familiar from stelae excavated at the South Tombs Cemetery, and is likely a solar symbol, perhaps also imitating the shape of a rock-cut tomb. Small areas of decoration can be made out on two other stelae fragments, possibly showing part of a standing human figure, and a section of an offering table.

A small but varied assemblage of burial goods was also recovered. They include items of cosmetic use, such as kohl tubes and applicators, a wooden comb and a probable wooden hairpin. There are other more obvious ‘ritual’ objects, such as a model mud ball with internal cavity. One grave contained barley associated with a piece or bag of textile, perhaps connected with the sustenance or resurrection of the deceased. There were also items of faience jewellery, including beads, pendants and finger rings.

New insights on burial textiles

Organics are particularly well preserved at this cemetery, and one of the side effects of this is the survival of a number of naturally desiccated individuals. These have proven particularly valuable for the study of burial textiles. Textile is widely represented at all of the Amarna pit-grave cemeteries, but it is usually so heavily deteriorated that little can be said about its form or function. Several of the desiccated bodies from the North Cliffs Cemetery, in contrast, have very well preserved textiles.

Noticeable differences were observed here in the way the dead were prepared for the afterlife. One approach was to wrap the body in textile strips, the typical ‘bandages’. Pieces of textile filling were sometimes inserted to pad out the shape, and textile ‘ribbons’ then used to secure the bandages in place. A variation saw the body wrapped first in strips, and then enclosed in a large piece of fine cloth used as a shroud. Some individuals seem to have been wrapped only in a shroud of fine cloth, or enveloped in several large pieces of coarser textile. One individual provided the first clear evidence from the Amarna pit-grave cemeteries of burial solely in a garment, here a bag-tunic. Whether the tunic was worn by the deceased in life or was made for the purpose of burial only is impossible to know, but it is a type of garment commonly worn at the time by men and women alike. Other garments were also seen on two other individuals: one headband, and a possible loincloth. In these cases, the deceased had also been wrapped in additional textile.

Sofie Schiødt excavating a grave with very well-preserved burial matting.

The Amarna Project

A preliminary typology of burial textiles has now been developed and this will be applied to the Amarna cemeteries as a whole. This work shows that while there is little indication that preservatives were introduced into these burials (although no scientific testing has been done), considerable efforts were made to protect the body with textile, in some cases seemingly to preserve the original shape of the body as well. Burial in clothing is an interesting variation.

Ceramic study

In contrast to the quality of preserved textile, the pottery from the North Cliffs Cemetery is of consistently poor condition due to water and salt damage, meaning that much surface detail is now lost. The majority of the vessels examined to date are closed forms of Nile silt clay, including ‘beer jars’, with a smaller number of sherds from large open vessels (hearths) also present. Marl clay sherds are much rarer but include fragments of miniature vessels, a type also present in the South Tombs Cemetery ceramic assemblage.

Reused sherds occur frequently in the excavated burials of varying sizes, the majority being Nile silt with significantly fewer reused marl clay sherds. Many of these sherds were probably used as ‘spades’ during periods of looting at the cemetery. A small number of Late Roman sherds may indicate the date of one of these phases of robbery.

Overall, the pottery recovered from the North Cliffs Cemetery is broadly consistent with the forms excavated at the South Tombs Cemetery, as noted by Pamela Rose in her initial assessment of the material in 2018. Continued study of the assemblage will help to shed light on the socioeconomic status of the individuals interred here, and provide a dataset for detailed cross-site comparisons between this cemetery and others at Amarna.

Bioarchaeological perspectives

Recently completed analysis of the skeletonised human remains from the North Cliffs Cemetery is also providing important perspectives on the site and its population. In total, the remains of 57 individuals have been analysed. While their bioarchaeological profile shares characteristics with those from both the South and North Tombs Cemeteries, the individuals buried within the North Cliffs Cemetery are distinct and suggest the population from which they derived was less biologically taxed than the parent populations for the South and North Tombs Cemeteries.

The demographic profile for the North Cliffs Cemetery is consistent with what is expected for ancient cemeteries. Most of the individuals are adults (68 %), but there are some children and adolescents (32 %) ranging in age from infants to teenagers. Where it is possible to estimate adult sex, there is a nearly equal distribution of females and males (55 % female, 45 % male). Comparatively, this demographic distribution is more similar to the South Tombs Cemetery sample than the North Tombs Cemetery, and the conclusion that the former was the burial ground for a wide segment of the population also holds for the North Cliffs Cemetery. The North Tombs Cemetery, in contrast, has been suggested as a burial ground for a labour force of young, predominantly female individuals.

Although the skeletal remains are predominantly those of adults, examination of stature and teeth, which form during childhood, can provide substantial information about individuals’ growth periods. Adult stature is a measure of childhood health, as stature can be reduced when biological resources must be diverted from growth to protect against disease or when the resources are not present to begin with, such as the case of food shortage. The individuals in the North Cliffs Cemetery are taller than their counterparts in the North and South Tombs Cemeteries, by about 1–2cm. Additionally, the frequency of individuals in the North Cliffs Cemetery with deficiencies in the enamel formations known as linear enamel hypoplasias is substantially lower than at the other cemeteries (North Cliffs Cemetery 52 %, South Tombs Cemetery 76 %, North Tombs Cemetery 73 %). These horizontal bands of reduced dental enamel thickness represent the slowing of enamel deposition to an imperceptible rate, caused by abnormal rates of physiological and/or psychological stress – the body’s last ditch effort to stave off death. High rates of linear enamel hypoplasia suggest heavily taxed subadult populations. While these results do not contradict the previous findings that life at ancient Akhetaten was difficult, they do suggest that within the city’s population, there are individuals who fared better than others, and the North Cliffs Cemetery is seemingly the burial ground for one of these slightly better off groups.

Excavations under way at the North Cliffs Cemetery in 2018, as Gretchen Dabbs, Waleed Mohamed Omar and Ahmed Sayed (left to right) define the edge of an ancient grave.

The Amarna Project

Hallmark characteristics of the skeletal remains from South and North Tombs Cemeteries include high frequency of broken bones and arthritis, and the severity of this degenerative condition is extreme. The North Cliffs Cemetery sample includes broken bones and arthritis, but the frequency, severity and distribution of these conditions is different. The frequency of trauma in the spine and other areas of the body, for example, is less than half of that observed in the South and North Tombs Cemeteries. Both the frequency and severity of arthritis is also lower. Additionally, while arthritis in the South and North Tombs Cemeteries tends to be frequently distributed throughout the spine and the large joints of the limbs, in ways that suggests carrying heavy loads was a typical daily activity, in the North Cliffs Cemetery arthritis is more commonly focused on the small joints of the hands and wrists, with little represented in the larger joints of the limbs.

Analysis of the skeletal remains therefore suggests that the North Cliffs Cemetery may contain the bodies of individuals who were working in different occupations than the labourers identified in the North Tombs Cemetery and the more general population buried in the South Tombs Cemetery. The North Cliffs Cemetery individuals do not have the severe and frequent spinal trauma observed in both the North and South Tombs Cemeteries, nor do they exhibit the severe and sometimes debilitating degeneration of the spine and joints of the long limbs. Instead, they exhibit very minor degeneration in the spine and in the bones of the limbs, with the exception of the hands and wrists, where degeneration is common and not previously observed in high frequencies at the other cemeteries.

Amarna’s administrators?

In addition to the study of materials excavated at the site, the physical context of the North Tombs Cemetery offers important perspectives on its role, and its relationship to Akhetaten and its populations. The northern location of the cemetery suggests it may have served, at least in part, populations living in the northern part of the city. The North Suburb, a large area of settlement adjacent to the Central City, seems a particularly good candidate.

There can also be little doubt that the cemetery was deliberately positioned close to the North Tombs, which belonged to some of the most important officials at Akhetaten. Panehesy, for example, was in charge of overseeing the preparation of offerings for the Aten in the Great Aten Temple. It has been suggested that many of the people living in the North Suburb may have been mid-level officials, employed especially in the Central City. It is interesting that we now have a burial ground that is a good candidate to have served the North Suburb, positioned below the tombs of officials who must have directed large numbers of administrative and other personal, and with a bioarchaeological profile suggestive of a population that was less biologically taxed overall than those buried at the larger North and South Tombs Cemeteries. Are we seeing here a portion of Akhetaten’s population whose working lives were geared more towards administration and related tasks, including within the core of the ancient city, than to heavy labour?

These preliminary results are potentially of great value in terms of identifying variations in health, workload and experiences across the population of Akhetaten, and for supporting ideas that the city’s settlement areas may have been, at least loosely, structured according to the occupations of their inhabitants. The results demonstrate the significant social information that is contained in outwardly uniform and simple burials, enhanced by the remarkable preservation and short-term occupation at Amarna. The Amarna Project is a research initiative of the University of Cambridge (www. amarnaproject.com). Working with the Egyptian government and local communities, it seeks to research and protect the archaeological site of Amarna. Regular updates on work at Amarna can be found in the Journal of Egyptian Archaeology and in the Amarna Project newsletter, Horizon. To support research at the site, visit www. amarnatrust.com.

A selection of artefacts excavated at the North Cliffs Cemetery including a probable hair pin and kohl-set (left), a fragmentary stela (centre) and a frog amulet and comb fragment (right).

The Amarna Project

The Amarna Project is a research initiative of the University of Cambridge (www. amarnaproject.com). Working with the Egyptian government and local communities, it seeks to research and protect the archaeological site of Amarna. Regular updates on work at Amarna can be found in the Journal of Egyptian Archaeology and in the Amarna Project newsletter, Horizon. To support research at the site, visit www. amarnatrust.com.

Anna Stevens (Monash University / University of Cambridge) is Assistant Director of the Amarna Project and co-directs the Cemetery Project with Gretchen Dabbs (Southern Illinois University). Amandine Mérat is a freelance textile specialist and Anna Garnett is Curator at the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, UCL. The cemetery research runs as part of the Amarna Project, directed by Barry Kemp. We thank the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities for permission to undertake the work. Excavations at the North Cliffs Cemetery in 2018 were supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities and the 2019 study season was funded by the Egypt Exploration Society. Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed here do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.