8 minute read

The dark side of dark comedy

There’s no mistaking the incredible things comedians have continued to achieve through their performances — for instance, Jon Stewart’s advocacy for 9/11 responders and survivors health care funding through “Never Forget the Heroes: Permanent Authorization of the September 11th Victim Compensation Fund Act,” passing after Stewart pledged his support to the bill in a scathing televised address against apathetic congressmen, mounting pressure on lawmakers. Because of their large followings and accessible conversationstyle speech, comedians can make complex political and social issues more digestible and engaging, especially in comparison to the dronings of painfully uncharismatic politicians, or jargonfilled newspaper articles. However, when comedians slip up or intentionally spread misinformation, these statements can be amplified through the media and cause ripple effects — low self-esteem and wavering acceptance within people, especially in youth.

It’s getting increasingly easy to step onto a stage and get messages spread on the internet, such as when Dave Chapelle did a set where he ridiculed transgender people. These comments and actions on stages are dangerous because of their potential to become widespread and eventually encourage or sanction hateful acts. In particular, Chapelle’s messages can potentially impact transgender youth by influencing the American public to adopt negative perceptions of transgender individuals. By pushing these videos to television and beyond, subconscious messages can normalize these “jokes’’ relaying harmful stereotypes and misinformation.

Advertisement

“Comedians in today’s society have the role of being social or political commentators,” junior Peter Aguirre said. “They also have larger audiences and as consumers, we constantly absorb their messages every time we engage in media.”

Because of this, a lack of feedback or criticism allows comedians to fall into the excuse of “it was just a joke.” This blanket statement enables a cycle of insensitive or inflammatory jokes to be brushed off as insignificant, while the number of communities hurt will keep growing.

Although it is important to hold comedians responsible for the words they say, criticism through mediums like cancel-culture are not productive in fostering change. While it’s difficult to hold respect for someone who has displayed a staggering lack of it, criticism should be civil and not degrading — allowing the feedback to actually reach the comedian. This can even take the form of simply not laughing at a joke. After all, death threats and slurs will often result in nothing but an eye roll or getting blocked, and may even embolden them to integrate even more extreme views into their jokes and sets.

“If my brother told a joke that I thought was insensitive or racist, I wouldn’t react. I’d say ‘That’s not funny, try again,’” Spanish teacher Michael Esquivel said. “If you’re a comedian, that means you’re constantly working on your craft.”

Often, the fine line between constructive criticism and cancel culture is hard to detect, as cancel culture is argued to both be someone’s free speech and while having the potential to harm the speech of others. Regardless, it’s good to set groundwork towards informative comments, rather than ones that immobilize comedians from speaking entirely.

“Extreme cancel culture is a dangerous road to go down,” librarian Amy Ashworth said. “If you look hard enough you will eventually find dirt on everyone.”

Although the appeal for many people coming to comedy shows is to listen to unfiltered dialogue, it doesn't take away from the responsibilities comedians hold as public figures. Because of accessible and engaging storytelling comedians produce, consumers are more likely to internalize the message being said. Especially when a comedian is talking about groups that they aren’t a part of — they should be more open to taking feedback, instead of labeling people ‘offended snowflakes’ or overly sensitive.

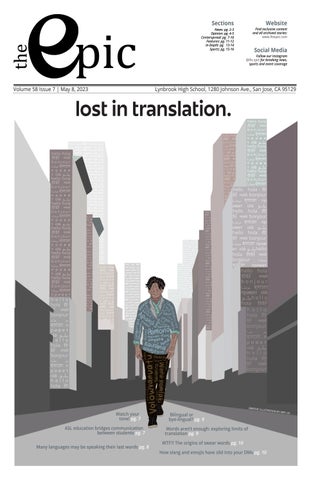

Welcome. Salut. Khush. Bienvenido.

Amdeed. Huānyíng. While these phrases extend a warm invitation, the various tonal changes in each language pressure the brain to perceive them differently. Thus, discrepancies in accents and tone switches often give rise to stereotypes, which can have far-reaching effects on both a regional and global scale.

Roman emperor Charles V declared, “I speak Spanish to God, Italian to women, French to men and German to my horse.” Although not as blunt, the conception of “romantic” versus “ugly” languages continue to prevail. Sociolinguistic studies have observed that the allure of a language is determined by how positively one views a community. In its most simple form, this phenomenon is evident in history and international affairs, where language perception is altered by former expectations. For example, when listening to German, one may often misconstrue syllables as harsh or commanding.

“Particularly, cultures that have languages that don’t use a lot of tones tend to find tonal languages almost like gibberish because they’re missing so much,” English teacher David Clarke said. “‘People who speak in Cantonese, they always sound like they’re arguing,’ is what the kids will say. It has to do with both stereotypes about the culture being imposed upon the language and the language itself.”

Language value is often linked to the prestige of the speaker — the increasing popularity of Chinese as a global language is linked to the country’s major economic growth; conversely, languages spoken by a less economically powerful group may not be seen in the same positive light.

Linguistic stereotypes are even pertinent in lighthearted children’s media. In “The Lion King,” king Mufasa has an American accent while Scar, the villain, dons a British one. Furthermore, Dr. Doofenshmirtz, nemesis of Perry the Platypus in “Phineas and Ferb,” has a German accent and often references the culture. The use of German, Eastern European and Russian accents for animated villains in Western movies is likely a reflection of the U.S.’s hostility toward these countries during World War II and the Cold War. In one study done by sociolinguist Calvin Gidney, which analyzed random samples of television shows, a majority of heroic characters were American-sounding. By symbolizing defeat of a foreign threat by an American hero merely through accents, American media places the U.S. on a pedestal for younger audiences as they are developing views of the world.

“As long as the media fed to our children perpetuates these harmful stereotypes, the next generation will continue to contribute to negative ideas surrounding specific groups,” Intersections club president Vineeta Muvvala said. “It’s up to us to change the narrative and promote a more inclusive future, starting with television.”

The language processing center of the brain attempts to form patterns out of foreign stimuli. When responding to words or sounds that cannot be interpreted, it resorts to a more basic understanding based on tone. As such, guttural and more consonant-based languages are taken to be brash or

BY SRUTHI MEDEPALLI AND SAMIYA ANWAR

harmful, while more harmonic and vowel-heavy languages are perceived as more sophisticated or advanced. Languages like Mandarin consist of many tonal changes, whereas those such as French are relatively smooth-sounding. While this doesn’t impact native speakers, these shifts in tone or lack thereof influence how foreigners view various cultures. Arabic, one of the most frequently misunderstood languages and difficult to learn, is spoken throughout the Middle East. The center of much political conflict and controversy, confusion surrounding Middle Eastern politics can be compounded by views of the languages spoken there.

“As a mixed person, people are often surprised that I speak Spanish,” junior Peter Agguire said. “Especially with my parents, I do feel my family is treated somewhat differently when we’re speaking our native language instead of English in public.”

Even within the U.S, the wide variety of ways to speak English create preconceived notions about certain geographical areas. Discrepancies between the timing and rhythms of southern English dialects in comparison to northern speech styles have contributed toward beliefs about the competency of residents in these regions. Southern “drawl” or “twang” is characterized by slower syllables and exaggeration, which can become associated with struggling to properly comprehend English, form words or think

Harsh opinions concerning the culture and language of certain groups typically bounce off each other. The South’s historical resistance to change and focus on traditional values has also contributed to slow-paced ideas of the South. In another example, stereotypes placed on African American Vernacular English judge the language for its colloquial tone and increased number of contractions or slang. The extent to which linguistic stereotypes are based on culture, or that cultural stereotypes are linked to language, remain hazy. Of 201 Lynbrook students polled, 87.5% agreed that stereotypes could be formed based on their

“People tend to think of those speaking Southern dialect as being ignorant because they take longer to say things,” Clarke said. “But that’s also an effect of the juxtaposition between that accent versus what you might call a common, stereotypical, newscaster English.”

As the world becomes increasingly global due to connections from social media and the Internet, language will adapt to change. Phrases across the world have begun to insert themselves into American English. Yet, stereotypes concerning specific vernacular and accents continue dividing people, and whether they will persist remains unknown.

Many languages

Be Speaking Their Last Words

BY ANUSHKA ANAND AND APURVA KRISHNAMURTHY

As English continues to globalize and be prioritized over other languages, language isolates are left behind. Many communities lose a part of their culture as younger generations forfeit a link to their heritage and identity.

“Languages tell you about culture and act as the memory of older generations,” freshman and Shanghainese speaker Cindy Tao said.

There are over 7,000 recorded languages spoken in the world today, about 35% of them being endangered. A language dies when its last known speaker dies. According to the Language Conservancy, nine languages die every year.

Some languages die out quickly when small communities are wiped out by disasters. El Salvadoran speakers of the indigenous Lenca and Cacaopera languages abandoned their languages to avoid being identified as natives after a widespread massacre in 1932. The Dunser language of the Papua region in Indonesia has only a handful of remaining speakers after flooding in 2010 devastated the Dusner village.

“The Cherokee tribe had a written language which was wiped out in an attempt to Americanize,” Clark said.

In the digitalized age, online or televised content tends to cater to society’s most prominent languages. Children in multilingual homes are often exposed to the most dominant language media from their area, making them more accustomed to the dominant languages during a crucial age of language development. As this content does not favor indigenous languages, populations lose familiarity with them, especially with the most integral parts such as colloquialisms, making it harder to pick up native languages later.

Colonialism is one of the leading causes of linguistic endangerment in areas with large indigenous populations. Historical emphasis on assimilation and suppression of indigenous languages promoted attitudes of cultural superiority, as proficiency in European languages was viewed as prestigious and could further oneself in a colonized society.

With the globalization of English came English schools, using styles of instruction in English throughout Asia and non-English speaking European countries. Younger generations begin to lose proficiency in their native dialects as English is placed at a higher importance. “Historically, languages have really been a political issue because they’re such a powerful tool,” Clark said.

Immigrants often prioritize learning English to bring more economic success to future generations.

Many second-generation U.S. immigrants do not speak their native language fluently because it is more economically and culturally beneficial to speak English. However, elderly speakers of a language are often left behind in rural communities, holding on to the fleeting traces of the language as others begin to forget it.

“It’s sad because we can see languages disappearing for newer generations,” Tao said.

Preservationists have been working to revive endangered languages as these languages are closely linked with regional or ethnic identity. For instance, Hebrew died out as a colloquial language in the 2nd century but was revived in the 19th-20th century. The language was continued through religious mediums as well as used in scholarships causing it to come back in prevalence. Now, it is the first language for many in Jewish countries.

Languages that are considered “dead language” are often commonplace within academia. Many high schools and higher education institutions offer classical languages such as Latin, Greek and Sanskrit despite the former two not having any native speakers. The efforts have proven influential in reinvigorating these languages as there are roughly 25,000 native Sanskrit speakers and such education promotes the culture and furthers the language into future generations.

Preserving languages maintains longstanding cultures. Spoken words are linked with values and traditions which can be passed down through generations, which enable speakers to connect with older generations. As speaking languages connect a person to their nation’s history, it also gives the speaker a sense of personal identity. When languages are lost, a part of a culture is lost.

“You lose the language, the history and an understanding of the people,” Clark said. “Then the whole world just becomes too homogenized. The diversity makes a richer world.”