Feldenkrais

Front Cover Gabriel Hartley, Chuo Line, 2023, projected cellphone footage on hemp with pastel and ink and embedded wooden structure, 60x40cm. Video still

Inside Front Cover Gabriel Hartley, From the Studio, 2024, projected cellphone footage on silk with embedded ceramic, 17x30cm. Video stills

Front Cover Gabriel Hartley, Chuo Line, 2023, projected cellphone footage on hemp with pastel and ink and embedded wooden structure, 60x40cm. Video still

Inside Front Cover Gabriel Hartley, From the Studio, 2024, projected cellphone footage on silk with embedded ceramic, 17x30cm. Video stills

Contents

3 Letter from the Editor

5

When the Smallest Is Too Small: Overcoming Learning Difficulties in Math and Music with the Feldenkrais Method Adam Cole

18

First Things First: A Strategic Hierarchy for Successful Functional Integration® (Postworkshop Question and Answer Sessions)

David Zemach-Bersin

38

Horizons of Understanding: Rediscovering a Phenomenological Epoché with Maxine Sheets-Johnstone (A Feldenkrais® Teacher Training)

Katarina Halm

48

Anatomy and Self-Image

Alan S. Questel & Jay Schulkin

56

Alternative Paths to Mindfulness: An Integration of Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) with Feldenkrais Method® Awareness Through Movement® (ATM®)

Zoi Dorit Eliou

78

Contributor Bios

Letter from the Editor

In their article “Anatomy and Self-Image,” Alan Questel and Jay Schulkin use the phrase “links and associations” to evoke the role of connection in human movement. The tactile, poetic elaboration is relevant to all five pieces in this issue of The Feldenkrais Journal ™ and without having to think too much, spontaneously, we have our theme.

Adam Cole, our new Assistant Editor, who has served on the Editorial Board for over a decade and written several thoughtful articles of his own, contributes “When the Smallest Is Too Small: Overcoming Learning Difficulties in Math and Music with the Feldenkrais Method®.” Cole makes an eloquent case for connecting relatable stories and movements to teaching math and music notation both for beginners and those who struggle with advanced concepts.

David Zemach-Bersin’s “Postworkshop Question and Answer Sessions” from his “First Things First: A Strategic Hierarchy for Successful Functional Integration®” show how Q&A sessions often reveal the fruit of learning for client and practitioner alike in our online lessons. The accompanying video—sensitively arranged by Juniper Perlis, Managing Producer at Feldenkrais Access®, and Peter Ahl, intrepid designer at Dandelion studio—further illuminates Zemach-Bersin’s vision.

In “Horizons of Understanding: Rediscovering a Phenomenological Epoché with Maxine Sheets-Johnstone” Katarina Halm brings together stories from her studies in the Feldenkrais Method, martial arts, and philosophy, linking memories already marked by the bonds that develop between students. It is a treat to read Halm’s account of studying with philosopher and dancer Sheets-Johnstone, a longtime friend of the Feldenkrais community, who seems to be as sensitive a teacher as she is a thinker.

In “Anatomy and Self-Image,” Questel and Schulkin reflect on the connection between the Feldenkrais Method and whole systems thinking. Questel’s clear, accessible style will be familiar to many from Feldenkrais trainings. Schulkin explored health and well-being through lab research, papers in top-tier journals, and popular books on neuroscience. The essay published here is a testament to Questel and Schulkin’s capacity to communicate the big picture, a talent facilitated, no doubt, by their decades-long friendship.

“Alternative Paths to Mindfulness: an Integration of Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) with Feldenkrais Method® Awareness Through Movement® (ATM®)” is an innovative paper by Zoi Dorit Eliou, who joined our Editorial Board this year. Eliou’s detailed account of

the connection between DBT and ATM is a gift for the Feldenkrais community and the field of psychology. What promising connections! May the relationship grow!

Ours is a story that still unfolds. The utility of connecting ideas from diverse disciplines—the bedrock of Moshe’s genius—may also be a pathway to wider recognition and the expression of our work in ways we could never expect. We hope these original, robust connections inspire you to weave your own instincts into the fabric of human movement and the practice of our glorious Method.

—Helen MillerWhen the Smallest Is Too Small: Overcoming Learning Difficulties in Math and Music with the Feldenkrais Method®

Adam ColeAs practitioners, we are often content to trust the Method rather than explore why the changes in our clients are so powerful, and why the Method may succeed where other approaches have failed. But how exactly does the Method facilitate learning in our clients? How does that learning assist them in making specific, significant changes to themselves?

1 Tom Dennis, “On seeing atoms,” UND Today (blog). University of North Dakota, Dec 3, 2019. https://blogs.und. edu/und-today/2019/12/ on-seeing-and-movingand-marveling-at-atoms/

2 Jeanne Bamberger and Andrea diSessa, “Music as embodied mathematics: A study of mutually informing affinity,” International Journal of Computers for Mathematical Learning 8, no. 2, (May, 2003): 123-160.

We can’t look at an atom with a regular microscope.1 The atom is too small to disturb the waves of light significantly for us to register them. While there are ways to work around this problem, the dilemma of trying to see an atom creates a great analogy for us as learners.

When we teach little kids math or reading we run into a similar sort of problem. Jeanne Bamberger calls it the conflict between “units of perception” and “units of description.” A unit of description is the smallest division we can make in order to describe something. It may represent a small thing like a “variable” (the x in algebra), a vocable like “ph,” or a “quarter note” in music notation.2

These units of description are the building blocks of any notation system. They give us the opportunity to distinguish one element of

information from another and to state exactly what we mean, promoting clarity and precision. Notation systems made up of these units, the alphabet for example, greatly expand our power to understand and teach what we know.

In music, the expression “quarter-note” refers to a particular duration of sound. In anatomy, the abbreviation “T1” refers to the first thoracic vertebrae. These are both examples of units of description.

The difficulty with units of description for someone new to a subject they are learning, especially a child, is that units of description often have meaning only as a part of a whole. For example, the letters of the alphabet on their own are largely meaningless. Trying to explain the function and uses of these units of description is a little like expecting someone to recognize an image when presented with a sequence of jigsaw puzzle pieces.

Most of us must experience and communicate our knowledge instead through what Bamberger calls “units of perception.” Units of perception are the smallest divisions of information that we can take in while still maintaining our understanding. A unit of perception may contain many units of description.

As an analogy, a dot might be a unit of description, but you’ll need to see a lot of dots to recognize a picture made of dots. The smallest part of the picture you can recognize as something other than a collection of dots will form a unit of perception. Anything less and it’s just dots.

The expression “the back of my hand” refers to a part of the body which has no anatomical definition, but it is still useful. “The House of Representatives” may be as specific as most people need to get when they are discussing political representation. These are both examples of units of perception.

In this paper we’ll explore the difference between these two ways of communicating information. We’ll also make the relationship between the Method and other types of education clearer by exploring this topic in two subjects that challenge many learners, namely music and mathematics. We’ll begin with a typical dilemma that relates to our work as Feldenkrais practitioners.

Weber-Fechner and the learning dilemma

Imagine you are lying on the floor and you feel a lot of tension in your back. It’s hard for you even to be still and think about what’s going on. You squirm and reposition yourself, but you cannot get comfortable. Someone comes over to you and puts their finger on your spine, just below the base of your skull. “That’s your problem,” they say. “If you can get that to move, you’ll feel much better.”

A single vertebra in the neck, held a few centimeters to the left by chronic muscular tension, will impact the carriage of the head, the mobility of the shoulders, and the balance of the weight over the knees and feet. Over a period of years, this may impact a person’s vision, balance, and create damaging wear on the joints and ligaments. Clearly the answer is to move that vertebra a few centimeters to the right. Get it back in alignment. A tiny movement … what could be simpler than that?

And yet the idea of being able to locate a single vertebra in our awareness, much less to isolate its movement, is monstrously difficult, if it is possible at all. Even if the vertebra were to be identified by touch and physically moved, its displacement is connected to a number of other elements of the person—physical, mental, and emotional—and its relocation would not make “sense” to them in a way that they could maintain it without continual conscious effort.

The Weber-Fechner Principle suggests that, in learning, a small stimulus will be more valuable to us than a large one, because the smaller one will have more of an impact on our sensation and intellect. Moving that tiny vertebra should be of more help to us than moving the entire neck. And yet we know as Feldenkrais practitioners that this is not always the case, because the vertebra, the unit of description, may be smaller than we can perceive.

Why is it that we as Feldenkrais practitioners have been trained not to address that frozen vertebra as the problem? Why is it insufficient, even ineffective, to isolate it? To get some clarity, let’s examine subjects that are further removed from the idea of physical sensation, but which reflect on our inability to better ourselves.

What we need in order to learn about math

Children may be able to understand units of description in their own domain: one sock or a mark on a piece of paper may contain a world of meaning. However, in an area that is new to them like mathematics, we may be using units of description to talk about the subject, and those units may be too small for them to perceive.

In fact, due to the precise nature of mathematics, teachers may feel obligated to teach with units of description even while knowing that these concepts are difficult or impossible for the learners to understand without context. As an example, it makes sense to ensure that a student knows every step of the addition algorithm so that they can do it correctly.

1) Write the first two-digit number. 54

2) Write the second two-digit number under it. MAKE SURE THEY LINE UP.

3) Draw a line under the numbers. Add a plus sign just left of the lower number.

54 + 96

4) In the second column, add the 4 and the 6 vertically. Because 4+6 = 10 and having two digits under the line will confuse matters, “carry the 1” by putting it above the first column. 1 54 + 96 0

5) In the first column, add the 5 and the 9 and also the 1 you just carried.

Each step in this relatively simple addition problem deals with a unit of description. Unfortunately, if you teach the process step by step like that, children of a certain age (and some adults) lose track because of the length of time and the number of steps. Left to their own devices, they will forget what they’re doing before they’re done with the operation.

A student that already knows how to add this way might break the operation down into fewer, larger steps like, “Draw the numbers; add them together; don’t forget to carry the 1,” or they may even conceive of the whole thing as a kind of number-dance, relying on spatial aspects of the operation. Fortunate students are able to group these units of description together to perfect their ability to work through the addition algorithm. People whose minds do not naturally gravitate towards mathematical concepts must rely on a good teacher to connect the dots of the procedure for them, and in the absence of this kind of help, they risk never being able to do it.

Since most of us reading this know how to add two numbers, we can’t fully relate to the situation above anymore. So I’ll use another example, from number theory, which will put most of us in a place of unfamiliarity.

George F. Simmons, Calculus with Analytic Geometry (United States of America: McGraw Hill, Inc., 1985) 395.

If I add

1 + 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/4 + 1/5 …

on and on forever, you probably wouldn’t be surprised if I told you that the sum of all those numbers is infinity. You add forever, the number you get is “forever big.” Right?

But what if I told you that when I add

1 + 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/8 + …

on and on to infinity, that the sum of all those numbers is “2?” You add forever, and the number you get is just a number, and not even that big a number. Would you believe me?

You might, but if you’re smart, you’d want me to prove it. The result just seems too crazy to take on faith.

“Okay,” I’d say. “So imagine that if p is a positive constant, then the p-series

∞

∑ 1/np = 1 + 1/2p + 1/3p + 1/4p + …

n=1

diverges if p < 1 and converges if p >1.” 3

Unless you have a math degree, none of that means anything to you. I’d love to explain it so you can see what I’m talking about, so I try to show you what the sigma symbol means, what the fractions with the exponents mean, what “diverges” and “converges” mean, but by the time I’m done, you’ve already forgotten the question. Because the elements of this explanation refer to and modify one another, they are very hard to understand on their own without prior experience. A mathematician understands each term and how it relates to the others, so for them the units of description are the units of perception. For you, the smallest idea you can grasp might be how to add fractions. This is your unit of perception, and you may not be able to understand the meaning of enough of the details to decode my sentence and understand why my crazy math fact is true.

Units of description in music

This is equally true in a subject that is supposed to be “fun,” like music. Although the end result of music making is often quite joyous, the

4 Professional pianists are often asked to play music set before them with no opportunity to listen to it first. Music notation, ungainly as it is, provides a powerful tool for learning and reproducing music. Good reading skills are of great benefit to the player.

process of learning the skills required to make joyful music is often less-so. The culprit can be too small a unit of description.

For example, a crescendo is an easy-enough concept—“get louder gradually”—and yet asking children to do so is more difficult than it sounds. Rather than increase volume incrementally, they tend to go from quiet to loud immediately, because the gradations of increasing intensity are too small for them to distinguish. In my work as a piano teacher, I teach many things like this which are not really very difficult once mastered, but which are difficult to master.

For example, in order to play a melody pianists have to execute a kind of a dance with their hand, one with several “dance steps”: Pinky plays A for two counts, thumb plays D for two counts, second finger and third finger play E and F# for one count, second finger plays E for one count, thumb plays D for two counts. It’s tedious to describe an elegant melody this way. Once played, it sounds like a cohesive, sensible whole, but it takes all those words to render it for accurate replication by a beginner.

After students hear the phrase, it’s often easy for them to sing it and sometimes to play it by ear. The phrase is an effective unit of perception in a larger piece of music. But when the melody is written in Western music notation consisting of quarter-notes, eighth-notes, and half-notes on lines and spaces, students have to reckon with each unit of description, deciphering it with their eyes.

Why should they bother? Can’t they just learn it by ear, if that’s easier? Some do.

But if they are to become experienced classical or jazz musicians, they will be in situations where they must learn a new piece of music by deciphering the notation on the page.4 Therefore it is necessary that they learn and understand the use of these little black marks. My job, and the job of all teachers, really, becomes keeping the students engaged while they struggle with all of these units of description that are beneath their perception.

5 Adam Wallis, “Paul McCartney admits he and the Beatles can’t read or write music,” Global News, October 1, 2018, 1:19 PM, https://globalnews. ca/news/4503916/ paul-mccartney-cantread-music/

Some methods of music instruction insist upon “sound before sight,” ensuring that music learners fully integrate musical ideas through movement and vocalization before they approach the written page. While this is a sensible, and depending on the instrument, sometimes necessary way of approaching the problem, it has pitfalls as well. Learners may become complacent with the skill of learning music “by ear” and choose not to pursue their knowledge into reading. In fact, many highly skilled musicians, Paul McCartney, for example, have never learned to read music.5 As adept or even astounding as Paul McCartney is, certain musical problems like composing orchestral music without paying assistants to help write out the music, or being able to look through a book of Chopin Etudes and decide which ones to play without spending an hour listening to them, remain difficult or completely out of reach for him. The benefits of reading music, which are surprisingly vast, will remain inaccessible.

6 Adam Cole, “Eight Minutes with Eric Litwin,” YouTube video, 8:06, 2022, https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=ZZbuke1mcT4

Getting past units of description— stories and analogies

Many students do not gain facility with mathematical ideas. They may be able to do just enough to get by, and will rely on computers, friends, and professionals to do whatever else needs doing. It is common to hear stories of “math anxiety” that began in elementary school and climaxed in high school algebra or calculus with a decision never to do math again.

If students could see the entire picture of a mathematical concept all at once, in the same way that they can listen to a melody, getting a sense of the end-goal and how each piece of a proof or example contributed to it, the units of description would not be an issue. Unfortunately, only experienced mathematicians will experience a math problem like a melody, while the rest of us will see it as a laundry list of baffling tasks, any of which, done incorrectly, invalidate the entire thing. How can students be given the big picture and kept engaged during the description of the smallest units of understanding?

One method to circumvent the problem is to add elements to the problem which do not alter it, but which make it large enough to register on our consciousness, perhaps even at an emotional level. In my interview with original Pete the Cat author Eric Litwin, an expert on the development of literacy in children, he suggests adding story elements to a simple math problem. “So in your math class about subtraction, add a verse … [Pete has] a jacket with ten buttons. Five pop off! What does he sing? My buttons, my buttons, my five groovy buttons! ’’ 6

Turning an abstract problem into a story can have a magical effect on children’s cognition. This, in effect, is expanding units of description into units of perception by adding elements to them that connect viscerally to the student, to their sensation, their sense of expectation, and to their need for resolution. However, unless the story can compel the students to want to solve a problem, they are more likely to remain caught up in the story itself, their imaginations taking them somewhere else, while they wait for the teacher to do the actual work.

7 Dor Abrahamson, “Strawberry feel forever: understanding metaphor as sensorimotor dynamics,” The Senses and Society 15, no. 2, (2020): 216-238. https://doi.org/10.1080/174 58927.2020.1764742

Another means of circumventing units of description is by depicting the big picture via an analogy. In his article “Strawberry Feel Forever,” Dor Abrahamson discusses the effectiveness of the use of analogy on music instruction, giving the example of a cello teacher who wants to explain how the student should touch the neck of the instrument with their left hand to make the best sound.7 Rather than dictate the many individual movements and configurations for the fingers and the palm, the teacher simply suggests the player imagine they are holding a strawberry in that hand. The analogy instantly suggests the correct hand position and successfully ties all the elements of cello performance together so that the student is able to “grasp” a better way of performing with very little trouble.

8 Moshe Feldenkrais, “Part A, ATM #222,” in Awareness Through Movement Lessons from Alexander Yanai—Volume Five, trans. Anat Baniel, ed. Ellen Soloway (Paris, France: International Feldenkrais Federation in cooperation with The Feldenkrais Institute, Tel Aviv, Israel, December 1997), p. 1521. https:// ebin.pub/alexander-yanailessons-volume-5-5.html

The drawback of the analogy is that while the student now knows a way to do it, they don’t know why it worked. We have circumvented the units of description, but we’ve also lost the opportunity to understand and explore them. If we, the student, wanted to teach someone else what we’d learned, we’d be entirely dependent on the analogy to communicate our expertise.

The problem of movement and how Feldenkrais solved it

Let’s go back to our vertebra.

Feldenkrais understood that the chief problem of self-improvement is the inability of a person to differentiate a maladaptive choice in the body in a way that it could be understood, owned as part of the self, and improved. Essentially, he recognized that many of our problems come down to units of description of ourselves that are well below our perception. How could we engage with our sensation at the appropriate level to learn and grow?

It might be possible to improve the situation with a story or analogy. Many visualizations like, “You’re walking through a field of tall grass. Do you hear the ocean? Breathe it in and feel a release in your neck,” can bring us to states where we feel better, but then, like the cello student, we don’t know exactly what we did to get there. In the rush to “relief,” we lose the opportunity to discover something about ourselves.

Feldenkrais’ solution was to create a way to differentiate the elements of a function that fully engages the learner. Rather than ask someone to locate a vertebra, he creates a scenario in which the body is contorted in a way that constrains everything except the parts that are to be moved. The act of discovering what kind of movement is possible under these constraints becomes an intense exploration that fills a person’s perceptions and engages them emotionally while still effectively isolating the areas in question.

For instance, in the Alexander Yanai Lesson #221, “Opposing movements of the head and shoulders [part 2]—while standing on the knees,” Feldenkrais asks participants to put their right foot standing on the floor, placing the left hand next to it. Students are then asked to raise their right hand towards the ceiling and look at it. Finally, they are challenged to lengthen their left leg back and lift it off the ground.8 This movement is difficult, and Feldenkrais says so. Nevertheless, he remains engaged with the class, giving them hints about how to make the movement easier, reminding them to go slowly and suggesting areas to focus on—like the extension of the head forward and the maintenance of the eyes on the uplifted arm. The student is fully engaged in what is essentially the isolation of the connection between the lower spine near the pelvis and the cervical vertebrae that carry the head.

9 A variation would keep the learner’s bodily position intact while varying an aspect of the movement: its speed, its direction, its coordination or opposition to another body part. A transformation would change the orientation of the learner while essentially keeping the function the same: lying on the floor and reaching up towards the ceiling, versus standing on the feet and reaching forward. Variations add interest to the task at hand. Transformations disguise it so that the habitual appears novel. Some variations can be transformations—in order to vary the act of turning the head to the left, you can ask the learner to keep the head still and turn the shoulders to the right, which is also a transformation of the movement.

Feldenkrais also provides multiple vantages of a single idea. In any given lesson he provides variations and transformations of the movement to be examined, putting students in different positions and scenarios—on their backs, on their sides—all of which nevertheless keep the focus on the same functional behavior.9 Within the lesson just mentioned, students are asked to side-bend their neck in a completely different orientation from their usual lying-down posture, and to regularly check for improvement by examining the extent to which they can turn their head to look behind them.

On a larger scale, many lessons may share a single idea in common. The aforementioned AY lesson, #221, is one of a series that explores the connection between the cervical and thoracic vertebrae. For us as practitioners, being presented with a series of related AY lessons is similar to providing math students with a series of word problems all dealing with the same mathematical operation. Unlike the word problems, however, which are only of interest to people who like math, the ATM lessons compel us by stimulating our human survival instincts for balance and a sense of safety.

While the ATMs have Moshe’s handwriting all over them, Functional Integration lessons may be much more idiosyncratic to the practitioner. Whether a client finds relief due to a well-thought-out lesson, or to just an effective touch and compassionate intuition, will depend on their interaction and connection with the practitioner. However, the art of FI comes directly out of Feldenkrais’ exploration in the ATMs he created over the years. We are better able to serve our clients if we understand both the big picture of their organization and the details that are in play. With both, we can make clients aware of vital details that may be too small for them to see, but which are absolutely necessary for their improvement.

Potential for the Feldenkrais Method’s impact on generalized learning

Just as in somatic self-improvement, math and music education make important use of units of description. Depending on the learner’s expertise, this is either helpful or a complete hindrance to their learning. Can we borrow from Feldenkrais’ Method to improve the chances of a learner in an academic setting?

10 Adam Cole, “Music and math notation: Improving performance by moving through imaginary spaces” (Presentation, Hebrew University, October 23, 2018).

In a presentation at Hebrew University, I outlined the possibility that math and music notation systems, insofar as we use them as tools, actually extend our body schema in the same way that hand-held tools do, so that we ourselves are physically connected to notation that appears only on paper or in our minds.10 I went on to suggest that our

ability to use a notation system would then be dependent on the quality of “movement” and “functionality” in the interface between that notation and our physical selves. If, in order to grasp a mathematical concept, we must imagine numbers and symbols on the page moving around to transform into other configurations, then it serves us well to examine anything that might improve our ability to make those numbers move in our minds.

If we really are connected physically to notation on a page, then we can enhance our ability to use a notation system by becoming more aware of those parts that connect to it. If we are “stuck” by a particular unit of description, a relationship between two types of variables in math, or a thorny rhythm as depicted in music notation, we may be able to engage with it, not only in an intellectual way, but physically, with our whole selves. In order for this to happen, we would need a new way of teaching inspired by the Method.

Determining units of perception in music notation

When I teach music-reading, I explain to my students that the music notation system they are using is actually movement notation—it tells them how to move at their instrument in order to make certain sounds. That being said, the Western music notation system does not reflect the actual movement it asks us to make. In fact, Western music

notation uses images that are often at odds with both the movement and the sounds they represent. In this way, it can be an impediment to a musician’s ability to play something that sounds and feels easier than it looks!

For instance, two measures which would take the same amount of time may have different widths, and therefore suggest incorrectly that one is actually shorter in duration than the other.

In the example above, the first four notes take exactly as long to play as the 32 notes that follow them. Some of my students have been known to play the first four notes far faster than they should as a result of the way the music appears, then crash and burn when they hit the next 32 notes because they cannot sustain the tempo.

Furthermore, these notes, which translate into an elegant phrase

in the hand, resemble a frightening wreck of dots and lines on the page. Their appearance alone is enough to discourage someone from even wanting to play, much less decipher, the phrase. The only way to become adept at reading music notation is to learn to decode this non-representative notation, the symbols cueing us to make the movements which result in the music we want to play, much the way “ph” in the English language cues us to make the sound “f.”

For this reason, I spend a considerable amount of time calling attention to the difference between our physical movements as pianists and what we see on the page, so that students are aware of it. I encourage my students to make marks with a pencil in the music in places where the notation is visually misleading. Their individualized marks represent the movement they need as they envision it, and their personalized symbol added to the notes converts a hard-to-decipher phrase into something big enough for them to comprehend.

I also ask them to count the beats of the meter out loud while they play. Coordinating the eyes while engaging the speaking voice does wonders for tying discrete notes to physical gestures. It turns the problem of reading dots into the more engaging problem of vocalizing at the precise moment the eyes hit a spot on the page.

The act of counting “1, 2, 3, 4” while playing a more complicated rhythm like what you’d tap out for the lyrics, “I’ve been working on the railroad …” engages the students in other ways as well. There are deep neurological connections between the hands and the mouth that may be activated,11 and of course when a student is counting, they are also breathing in time to the music. All of these elements combine to clarify the units of description that are the written-out notes of this folk song.

This is most important because students, especially young beginners, are interacting with a piece of music much more slowly than it is meant to be played. They must learn the music by playing at a speed they can manage. But if you sing “I’ve Been Working On the Railroad” at a quarter of its normal speed, the identity of the song, the melody and rhythm, do not sound like music. The very thing that should compel them to want to learn to play is missing, and counting can serve to keep them connected to what they are doing until they can increase their playing to a speed at which it is recognizable as music.

In both marking and counting scenarios, I teach the students to group the units of description (the individual notation symbols) into units of perception by explaining them as movements they are to do rather than as discrete concepts they are to understand. This is consistent with good sound-before-sight music education philosophies. However, because I can connect reading to movement, I am able to engage in a study of notation while we are learning rather than put it off and risk losing the opportunity, using units of perception (playable phrases) to give us more familiarity with units of description (notes on a page).

Rethinking math instruction

We might take a similar out-of-the-box approach to math to make it both more compelling and more comprehensible to beginning students. Imagine a teacher who discovers that their elementary math students are having difficulty understanding how to “carry the 1.” Instead of writing it on the board and explaining it for the 10th time in a tired but hopeful voice, then asking the students to work out 50 examples on a worksheet, punishing them with a red “x” for each one done wrong … a teacher might create a scenario in which the students are to visualize the number 10, where the 1 is gradually moving away from the 0 and sailing up to the upper left corner. The teacher might find a way to translate this idea into a physical challenge where the eyes are moving in a diagonal while the head and shoulders stay fixed, and then enhance the game by reversing the movement so that the eyes stay fixed and the head and shoulders move.

To make the movement of the 1 large enough to register on the students’ perception, it must be attached to a compelling need. Having them stand on one foot while they move their eyes during the visualization would require them to balance, and the desire to avoid a fall would more completely involve them. Having them switch feet to see which one is easier to balance on would add further interest to the exploration.

If a math teacher wished to argue that this is a lot of fuss for a simple operation, I’d counter that this is exactly the point. That students may be incapable of understanding the tiny act of carrying the 1 unless it is tied to a much bigger unit that engages them as people. And the more potent the engagement can be to the act of “moving the numbers in their minds,” the easier it will be to understand and enact.

Is it possible for us to use these concepts to make clear the infinite series problem I posed at the beginning of the paper? At the very least, it may be helpful for us to understand that we are hindered in our ability to understand why adding one set of fractions forever takes us to infinity, and the other set of fractions takes us to 2, by the very fact that sophisticated mathematical building blocks may be too small to understand in isolation. For us to gain the competence to be able to follow a straightforward explanation we would have to enlarge each of the small concepts into something that is meaningful to us through our curiosity or our instinct for self-preservation, so as to integrate them into our thought process and even our sense of self.

To reach such familiarity with the small concepts, we would have to be in an environment where we could play with them the way a child plays with blocks, perhaps on a website which allows us to change any element to see what the results would be upon the big picture. Potentially more compelling, a teacher could put us in a mutual learning situation that, through collaboration, assists us in feeling a human

12 Paul Lockhart, A Mathematician’s Lament (New York: Bellevue Literary Press, 2009).

connection with the other students. If that situation made clear the idea of movement that we could see, or even enact, it would speak to us at the level of the nervous system and perhaps trigger an intuitive connection with these concepts, an experience that I suspect the best mathematicians come upon naturally.

Dr. Paul Lockhart in his famous essay, now the book A Mathematician’s Lament, calls for the elimination of “standard” ways of teaching math, even changing well-worn vocabulary, in favor of creating a classroom environment in which students are given compelling, real, and interesting problems to solve, not on paper alone, but physically, and through conversation with one another.12 In this way he is working to overcome or even avoid the students’ collision with the units of description. Perhaps if his way of thinking were to be adopted, math teachers would no longer consider it sufficient to combine the bare essentials and hope that the students could add them together to get as far as they need to go.

Conclusion

My understanding of why my learning and teaching strategies have been effective has come directly out of my investigation into the Feldenkrais Method. It has allowed me an opportunity to observe myself and my students’ increasing abilities through the lens of somatic engagement, and to overcome barriers to understanding brought about by a wall of impenetrable details. I am fortunate in that I have been able to improve the learning and performance of students who do not have access to regular Feldenkrais lessons.

Feldenkrais taught us that we can take elements that are too small to mean anything by themselves and enlarge them in our imagination and our curiosity. Through ATMs and FIs we differentiate the tiniest, sometimes pointless-seeming tasks out of a larger functional movement so that we, and our clients, can play with them. Once these elements are understood and reintegrated into the larger system, it changes our understanding and our capacity to act.

It’s my hope that by better understanding what we are doing as practitioners, we can use Feldenkrais’ insights in the development of his Method to improve our ability to teach the arts and sciences. Rather than abandoning units of description as being too difficult for the student, or subjecting our students to them and hoping they will somehow absorb them, we must find a way to make the units of description richer and more compelling to the learner. If we succeed, not only will we be better Feldenkrais practitioners, but we may be able to participate in the education of a new generation of mathematicians, musicians, and other learners that currently are lost to us.

First Things First: A Strategic Hierarchy for Successful Functional Integration®

Postworkshop Question

David Zemach-Bersin and Answer Sessions with An Introductory Note

David Zemach-Bersin

In the Fall of 2021, I taught an online advanced training called First Things First: A Strategic Hierarchy for Successful Functional Integration. A month after the workshop, two question and answer sessions were held for the participants. Raz Ori and Anastasi Siotas both assisted me by bringing the questions forward during the first session. Raz assisted during the second session.

What follows is an edited transcript of those two Q&A sessions. To help create a context for this material, here are a few paragraphs from a letter I sent to the participants:

Moshe Feldenkrais would often say, in some form or other, “Improve the person, not their problem. If you improve the person, their difficulty

will improve.” I believe that this dictum speaks to one of the essential reasons he was so successful in improving and transforming human abilities.

Feldenkrais is saying that the vast majority of human musculoskeletal problems are reflections of poor organization and that as a person’s fundamental organization improves, the dynamics that underlie and compound their difficulties will be diminished. He understood that there is a way of being “organized” that is optimal for all human beings; a particular organization between our skeleton, nervous system, and musculature. Approximating this organization, then, gives us our best possible options for pain-free, efficient, easy, and effective movement or action.

Good organization brings us into alignment with the fundamental biological principle of the conservation of energy, i.e., action and adjustments to gravity are realized with the minimum expenditure of energy. Good organization—as defined by Feldenkrais—provides or enables the ability to move from the standing or sitting position in all primary or cardinal directions with a minimum of muscular effort. Hence, effective action is potentiated by good organization. As an added and significant bonus, minimum muscular effort maximizes our ability to make kinesthetic-sensory distinctions, thereby facilitating the creation of useful information.

The neutral neuro-muscular-skeletal state that is synonymous with good organization reduces the attraction and the burden of our past adjustments to culture, trauma, punishment, and anxiety. The neutrality of good organization leaves these habits and adjustments without a muscular and sensate basis. Where we once had compulsion, we now have choice.

As human beings, we are much more alike than different. And, our difficulties are more alike than different. I believe that if we have a clear understanding of the hierarchy of criteria for optimal self-organization, we can better realize Feldenkrais’ dictum to “improve the person and not the difficulty,” and make our practice of Functional Integration more effective.

First Q&A session

David Zemach-Bersin : Hello everyone. I am delighted to be joined today by my colleagues, Raz Ori and Anastasi Siotas. With their help, we’ll have not only my answers to your questions, but also an opportunity for dialogue between the three of us.

Raz Ori: First, we have an interesting question regarding the title of your workshop, First Things First. You mentioned being inspired by the virtual Functional Integration (FI®) lessons that you were giving during the beginning of the Covid pandemic. You talked about how those virtual

lessons clarified and amplified your understanding of what you believe is the first and most important thing for us to direct ourselves toward. Can you share a bit about your experience giving virtual FIs and how it relates to the theme and title of this workshop?

David: With the virtual FIs, because I could not feel with my hands, I was unable to feel the fine, intimate details of a person’s organization. Nearly all information had to be visually inferred. In that vacuum, my lessons became more strategic and general, and the results stunned me. Certain remarkable generalities came forward. Most people, with almost any kind of acute or chronic difficulty, have certain things in common. There is a protective “forwardness” to their bearing and a lack of mobility in their pelvis. I felt that with all the limitations of working on the computer screen, a veil was pulled away, and I realized that I was consistently dealing with something of universal and essential importance. It reminded me of something that Moshe said in Tel Aviv one afternoon, in reference to someone he had asked me to give an FI lesson to. He said, “Just improve the person, not their problem.” We don’t have to dig very far to understand what Moshe meant by this. When I presented the idea of this workshop to Anastasi and Raz, I told them that I wanted to “plant a flag” on this spot. I wanted to say, “If you want to be effective, this is the way to be effective.” You see, Moshe was not speaking metaphorically. He was not being the Zen master that I thought he was when I was 24 years old. He meant literally improve the person. And, this is not an abstract idea. In both the Elusive Obvious and Body and Mature Behavior, Moshe offers us a roadmap for what he believes is the best organization for enabling effective movement and action. And, as long as a person’s center of mass is forward, and their abdominal muscles are over-contracted and “held,” that best organization cannot be achieved or approximated.

Anastasi Siotas: I’d like to connect the idea of improving the person with your observations about working remotely. You’re seeing the student through a two-dimensional medium, yet somehow, your years of experience touching people informed a three-dimensional way of viewing. You saw certain common dynamics, like the forwardness. You felt that the constraints of the situation helped to highlight essential aspects of their organization.

David: Exactly.

Raz: On one hand, you are presenting a very fundamental concept, but on the other hand, the repertoire of Functional Integration lessons that you demonstrated in the workshop were quite sophisticated. In regards to applying these Functional Integration schemas, how do you adapt these lessons to the public? When working with an older population or with people that have more restrictions, how do we adapt these ideas?

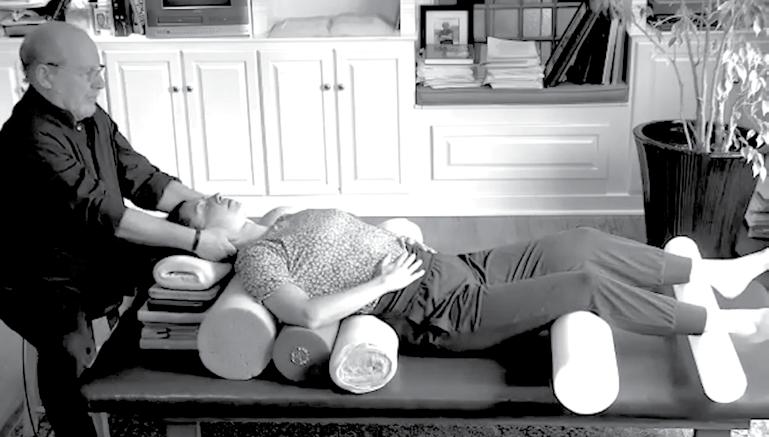

David: Let’s set aside the details of the FI demonstrations that were shown in this workshop. There was a consistent idea throughout all of them, which had to do with the mobilization of the lower back, the inhibition of the abdominals, and the extension through the spine growing with the head and neck being able to come up and back. This was a repeating idea in every single one of those FI demonstrations. [Fig 1] So, let’s say that I am working with a student and they are only comfortable lying on their side; how can I use this strategy? Can I bring their pelvis back? Can I bring their head back a little? Can I work with the idea that Moshe explicates in many ATM® lessons, of sticking the tush out and taking the head back as in, for example, AY 524? Can an older person bring their arm back a little bit while lying on their side? Oh, that’s painful? Well, maybe I can put a pillow under their arm. Bringing their arm back—even a little—engages the extensors of the upper back and the mid back, and now, if the arm is back like that, and I bring the pelvis back, well then, now we have the opportunity for a more coherent and unified extension of the entire back. This would be a less extreme way to do what I was doing in the FI demonstrations. Or, lying on the stomach, can we begin to work with the idea of simply lifting the head? Lifting the head might be the beginning of organizing the muscles of the back to act in a uniform, elegant, co-operative way, to create the anti-gravity function. This is what I tried to show in all of the workshop’s ATM lessons. Think of how many lessons you know, where lifting the head is involved. For that to be done easily, and for the head to be light, we must involve the entire back. By eliciting the whole, you are dealing with things that, from an evolutionary point of view, have stood the test of time. Simply taking the head back, provokes the muscles of the lower back to engage. That sounds like a beautiful starting place to me!

Anastasi: This brings up a secondary concept that you mentioned earlier about the inhibition of the abdominals. How do you take your head back if you cannot let go of those abdominals?

David: Exactly. It is impossible! There must be reciprocal coordination and as long as, or to the extent that there is parasitic effort in the abdominals, the extensors of the lower back and pelvis will be necessarily weakened.

Raz: People are eager to understand how to approximate the specific situations that you were demonstrating. For example, you often worked with people in the position of having their feet standing and knees bent, and lengthening from the knee in order to clarify the elongation along the spine, and also to clarify the relationships between tilting the pelvis forward, and the engagement of the extensors. But, what happens if a person cannot bend their knee? What happens if the person can stand their foot on the table, but their heel is far away from their pelvis?

Video medley for the First Things First Q&A: https://www.feldenkraisaccess.com/first-things-first-q-a

David: You can use these ideas in all your Functional Integration lessons, regardless of how many degrees the knees can bend. The essential thing to work with and toward is the engagement of the back and the inhibition of the abdominal muscles in order to allow those big powerful extensor muscles to work in the way that they are capable of, or evolved to. I agree that when I lengthened through the knee, the pelvis was tilting, the abdominals were lengthening, and the muscles of the lower back were contracting. But when the leg or legs are long, and I very carefully pull through, am I pulling the leg? No. I am measuring and sensing. I’m feeling the extent of the lengthening, and how the head of the femur is connecting in the acetabulum and tilting the pelvis. The pelvis can only tilt if the lower back muscles are able to shorten, and contract. The pelvis can only tilt anteriorly if the abdominal muscles are not inhibiting its movement. I don’t need to bend the knees; that’s not what made the lessons effective. It is the effective mobilization of the back, which we are interested in, and we can initiate this from 20 or 30 different places. I would say, let’s not worry about the details. Let’s concern ourselves with the larger ways in which the organization of the person is improving. Then, their problem, or difficulty, will also improve. This is the path toward improving the entire person and everything they do.

Raz: We have a similar question regarding bringing the pelvis to tilt off the table. Let’s say that’s too extreme for someone because of lower back pain, or they’re not prepared for that situation. The idea you demonstrated of using a flat towel as support or rolling it up as a cylinder both approximate tilting the pelvis. They’re both working on clarifying the relationships that you were just describing. [Fig 2]

David: Exactly. You’re bringing the pelvis to a ledge. That ledge can be a roller, or a flat-folded towel. Just as long as it gives the person and their nervous system the experience of their tailbone falling lower than the

rest of their spine. It doesn’t have to be an extreme, acrobatic situation of bringing the pelvis entirely off the table. When you think of the idea of successive approximations, then the platform or flat folded towel might be a first approximation, and the rolled up or cylindrical towel—which gives more dynamic oscillation potential—might be a second, or third approximation. I can use the flat towel as a way to raise the pelvis, which is still taking over some of the work of the flexors, i.e., the abdominal muscles which are inhibiting the strong extensors of the pelvis and back from contracting.

Raz: In relation to adapting these situations to people with real problems, let’s consider working with a person who has spondylolisthesis. Or, take another example of someone who has lost their lumbar lordosis and their back is round and perhaps they have spinal stenosis.

David: FI is the art of finding ways to make adaptations for the person on the table. Adaptations that insure the person can feel themselves without their habitual pain or discomfort. We must always remember Moshe’s strategic idea of small, incremental change that is safe and can be accepted by the person. Now, if I have somebody in front of me with stenosis and I see that they’ve lost their lumbar curve, I would hope to support them in a way in which they are comfortable and can begin to experience themselves relaxing their abdomen and engaging their back. But, it has to feel safe to them. There can’t be any discomfort. If there is, they’ll retreat. They’ll withdraw. The adaptation I mentioned a moment ago, of using something flat to elevate the pelvis a little, could be the most comfortable starting position for that person. It may be that you’ll need to have the knees higher, more bent. Let’s say that A is my static position, and that I have difficulty moving to B. If you can help get me to a place where I can move from A to B to A without discomfort, that could be so useful to me. It might be more useful to me than surgery because surgery for stenosis, spondylolisthesis, and sciatica is often ineffective. I’m reminded of one of Moshe’s lectures, I think it’s in Year Two of Amherst, in which he’s talking about correct posture. He says, “In Body and Mature Behavior, I said figure A is the correct posture. It’s better than B and C and D.” Then he says something to the effect of, “If I have Parkinson’s and you try and get me to be upright like A, well, A is incorrect for me.” It’s beautiful how he understood that what is correct for one person can be incorrect for another. What is correct is temporally based. It’s correct for me now, today in this moment, but in a year it might not be.

Raz: I’m thinking, what better way would there be to support the overarched lower back of someone with hyperlordosis than having them lie on their back, feet standing, and having a soft, nice roller behind the lower back? Not to overextend the lower back, but to support it? And, the flat soft padding that you put behind the pelvis can also go behind the lumbar spine.

David: That would be safe and effective. It’s a path that I use a lot: only a thickness of an inch or so, and very soft.

Anastasi: Yes, the muscles that are intensely tight there, have an opportunity to feel proprioceptive feedback and contact and let go. But at the same time, I think there is value to raising the sacrum and allowing the movement of the abdomen—with the pelvis forward—to allow gravity to work on those super tight lumbar extensors.

David: Sometimes the first approximation is to not even think about mechanically changing anything, but simply to provide a kinesthetic experience of lightness and pleasure. Does the person care about matching Moshe’s figure A? No! They care about not being in pain. They want to feel the way they did before their trouble began. They don’t seek to be an archetypal example of an ideal healthy back. They just want to feel good about themselves. As I watched Moshe work, it seemed to me that with his help, people felt that they learned not only a way of being organized, but a way of being in themselves that helped them to move away from pain and the things they did that created the pain.

Raz: What if you are already in the neutral position of your spine, and you’re not excessively bent to the side, or twisted, or turned, or flexed, or extended?

David: It’s important to always remember that what we might call a neutral or ideal spine has two concave curves. Some say, “A straight spine is neutral,” but nothing could be further from the truth. In a healthy spine, a well-organized, or ideal spine, there is a concave curve in the lumbar spine, and there is also a curve in the cervical spine. That means that from the neutral, when you arch the back more, the anterior or front portions of the vertebrae are moving away from one another. There is a lengthening in the front of the spine, produced by the muscles of the back contracting. What happens when a muscle contracts? The two ends of the muscle come together. If we fold or flex ourselves, well then, that’s opening up the back of the spine. The spinous process of one vertebra is moving away from the spinous process of another vertebra. The vertebra below it and the vertebra above it are moving away. But in front, what’s happening is that the anterior portion of the discs are getting acutely compressed. In a well-organized person, when the skeleton is supporting the person, the compressive force of gravity is going down through their skeleton and back up. When I’m well-organized, the distance between my vertebral bodies is maximized because my muscles are doing very little unnecessary work; they are not shortening me.

Anastasi: We’re talking about those lordotic curves, but we have a complementary kyphotic curve in the thoracic spine; an additional element which moves us away from the idea of straight. And there is a complementary, almost like a sine curve. If you think about your sacrum and your pelvis, that’s almost like another backward curve. It’s like a series of complementary curves which, when there is neutrality, work in concert with each other so that those spaces between the vertebral bodies are at some sort of even location, not necessarily folded forward with the vertebral bodies at the front close together and the back more open, nor the other way, where the back is closed and the front is open. As you said, then and only then can the flexors and extensors work in a beautiful rhythm that allows us to maintain length throughout our activities.

David: The synergy between the flexors and the extensors is dependent on the process of inhibition. So much of what we do in Functional Integration is to help and assist the nervous system to sense superfluous efforts, and inhibition is a key ingredient in this learning. There is a reciprocal relationship between the flexors and extensors. When my actions are being organized in the most efficient, easy, fluid way possible for me, there is a constant back and forth. It’s almost like the rhythm of breathing. It is precise and elegant. The entomologist Theodore Schneirla found in his research that the extensors were more involved in the function of going toward, and the flexors were more involved in the ability to withdraw, or move away from. I wonder, at what point did these two strands of muscle arise? Imagine two primitive fibers full of myoblasts, working together in a kind of “give and take” in order to create propulsion, in a liquid medium. It is possible that one muscle evolved first, a single muscle fiber that could contract and relax, contract and relax. But, as soon as you have two strands instead of one, the complexity of movement that becomes possible is extraordinary. You have a primitive nerve or ganglion that regulates those two strands, as they contract and relax in their reciprocal relationship. The essential problem for us, as human beings, is that we regulate this relationship poorly. Most of us live with both our extensors and their agonists, the flexors, contracted at the same time. Moshe understood that this is at the root of most people’s difficulties. Almost all Awareness Through Movement® lessons are based on the idea of improving that reciprocity, that reciprocal relationship between the flexors and the extensors.

Anastasi: What happens when we interrupt that reciprocal relationship?

Let’s take the example of the abdominals being held and unable to let go, preventing the pelvis from oscillating forward and back. How can we work with this inhibition? We might support that inability; that strand on one side that hasn’t been able to let go, and begin to restore the

capacity for that muscle. We support it and suddenly it lets go a little, and then there begins a dance between these two strands that brings us back to this sense of wholeness and we feel capable again.

David: Let’s also mention the biological value of co-contraction, because when there’s pain, we need that co-contraction. Why? Because the co-contraction inhibits movement and it is movement that is provoking the pain. We have to understand that much of what we see is the adaptation that a person may have made to trauma, or pain. Perhaps that co-contraction was valuable and helped to create the conditions for healing.

Raz: As biologically essential as these patterns of co-contraction are for survival and protection, we also know how destructive they are, and how they can become activated in a compulsive, patterned, automatic way.

David: Especially when deep fears or anxiety are involved. We have to end this session now, and I would like to thank Raz and Anastasi for their help.

Second Q&A session

Raz: I’d like to pick up where we left off in the first Q&A, when we were talking about the synergistic, or the reciprocal relationship between the flexors and the extensors. There is a very interesting synergistic relationship between the eyes, the head, and the pelvis. And you were talking about organizing the head and the eyes in order to look towards the horizon, and how tilting of the head downwards can tip our entire self-organization back into our habitual patterns. But what if we need to walk and we do need to look down, such as walking on an uneven trail or walking out in nature?

David: That’s a great question with a logical answer. Yes, we need to look down. Sometimes, you’re walking on a rocky uphill or a downhill path, and you’ve got to look down. If you’re walking on an uneven path that’s more or less flat, you can probably trust your feet more than you think, and you don’t need to actually look down as often as you think you need to look down. When walking on uneven terrain, it’s a good idea to keep your knees soft to that your hip joints can be soft even when your pelvis is not neutral. If you make your knees soft when you’re standing, you will feel that your pelvis drops a little, and there’s a slight flexion of the pelvis. So, if you want to be stealth, and you’re creeping very slowly, you will automatically bend your knees and your pelvis will flex a little bit. And your head is in the neutral looking towards the horizon. Moshe would say that this “ninja like” posture potentiates your being able to move in any direction, and that’s what we ideally want.

Raz: It’s really interesting what you’re saying about walking with soft knees. When walking barefoot, one does not stomp the back of the heel into the floor in the heel strike phase, because that would cause injury to one’s skin. That’s a privilege of walking with shoes on a flat surface. When walking barefoot, one touches the floor before bearing weight on the foot. There’s a very short period of time where the foot acts as a sensor to test the terrain before planting weight, before bearing weight on the foot.

David: I propose that if your knees are soft and you relax your abdominal muscles, and your shoulders and neck, then your foot can begin to act in that way, even with shoes on.

Raz: The next question relates to what you were doing in the lesson with the roller behind the pelvis, when you elongated the knee. The knee was moving away from the head, in the direction of the toes. And we were sensing the elongation through the entire spine, and noticing how it was being transmitted up the entire skeleton. And you emphasized exhaling as we were doing it.

David: Inhaling always “fixes” things in a particular way, especially in the thoracic spine. The spine should be able to move and extend in the lumbar area. If you hold your breath, you create a level of unnecessary difficulty.

Raz: One of the participants made a brilliant observation that when they turned their attention downward, toward the sensation of their feet when standing or walking, they felt that their eyes were being pulled downward. In fact, there is the ability to differentiate between the movement of the eyes, what you’re “seeing” kinesthetically in your mind’s eye, and where your attention is driven. Can you say a little more about that?

David: I would say that the most natural, organic thing is for the eyes to move with our attention. As William James, the father of American psychology highlighted, attention is telling the brain that something is very important. Moshe is concerned with this in many lessons, especially if you think of the primary line lessons, and the scanning lesson in the Esalen Notes. You see in those lessons that he understands that when your eyes move, your whole entire body is moving in response to the movement of the eyes. In other words, your eyes influence your musculature to such an extent that when you look with your eyes to the left, your entire musculature is organized to turn to the left. We can easily measure this with an EMG machine. By the same token, if I’m lying on my back and I look down toward my feet, we would be able to measure how

my abdominal muscles contract, and how my chest depresses. In other words, we’d find that both actions, looking down toward our feet, or up toward the heavens are whole body or whole self actions.

Raz: You were working also with the pecking movements of the head, bringing the chin forward and pecking the head forward. You mentioned that it’s a fundamental and an essential movement. How does that f

fit with the problem of forwardness? Isn’t having the head forward a problem in most people’s organization? [Fig 3]

David: Firstly, in the problem of forwardness the head is forward and down. If you have a stick coming out of that top of the head, it’s not just that it’s going forward of the spine as in pecking, but it’s also going downwards toward the ground. What is it that is essential in those pecking lessons? It’s the ability of the head to slide that little bit that it can on the atlas, and the atlas to move relative to the axis. That pecking movement helps to restore the organization of the cervical spine as it ought to be ideally. That is because when we slide the head forward, the entire cervical spine arches. At the very beginning of the movement, there’s a small movement of the skull relative to the first cervical vertebra. Then, the other vertebrae become engaged, and that movement can help anyone and everyone to begin to restore their cervical arch, and thus the free movement of the head and teleceptors. If the pitch of the head—for most people—is forward and down, even slightly, then their cervical arch is severely diminished. Our task has to be to somehow give the person the sensation of what it’s like to have that cervical arch. The beautiful thing is that the reorganizing properties of that movement are spontaneous. I’ll say that again: The reorganizing properties of that movement are spontaneous. Why? Because your brain and my brain recognize those movements and that organization

of the cervical spine as being what enabled us to stand up in the first place, and to walk in the first place. The linkages to those developmental phases are clear, and the advantage to the system is more than obvious.

Raz: This is also a paragon example of how the reciprocal relationship between the flexors and extensors is interrupted by the forward and down head position, and how the cervical curve is not only compromised, but compressed. When you’re doing the pecking movement, those relationships can recalibrate.

David: Absolutely. I was very lucky to be able to sit at Nachmani Street and watch Moshe work day after day. I would be understating it if I said that in 90% of his lessons, he worked with the head and neck at the end of the lesson. The person would be lying on their back, and Moshe would be supporting their head from behind and lifting it with those pecking movements, forward, right and left. This was probably the most frequent thing I saw him do at the end of a lesson.

Raz: Let’s go back to discussing the lumbar lordosis, but first, let’s have a clear terminology about the different positions of the pelvis; the neutral position of the pelvis, the pelvis being anteriorly tilted, and the pelvis being posteriorly tilted. If the superior part of the pelvis tilts backwards in relation to the pubic bone, that’s a posterior pelvic tilt. If the superior part of the pelvis tilts forward in relation to the pubic bone, that’s an anterior pelvic tilt. You said something interesting about elite athletes; about how their lumbar lordosis is often significant, maybe even pronounced, and that this gives them an advantage in the skills they’re performing. Can you say a little bit more about that?

David: This is very true when the sport involves exerting a great deal of power. Power is derived from the differential between where I am, and where I want to exert force. If I’m already forward, and want to push you backwards; I don’t have far to move myself without becoming unstable. I am able to apply very little power. But if I am further back, over my heels, and want to push you, well, now I have a much greater distance over which to produce that power. In addition, Moshe would say that the power of a muscle—of an individual muscle—is derived from the differential between it being relaxed and contracted. He would say a man with built-up muscles can never be the most powerful man in the room because the distance, or differential, between that muscle being relaxed and contracted is small.

Raz: The differential in length of the muscle?

David: The length of the muscle, that’s right. Moshe stated it as a question in his first or his second judo book: how do you explain how a

small, non-muscle-bound person can be so powerful in doing judo or jujitsu? There must be some secret there about the mechanics of how force is produced. For athletes, power is produced by the pelvis. Not only is it the largest bone, but the most powerful muscles of our body are attached to it; either at both ends, or at one end. The default position of their pelvis already has an anterior tilt to it. Which makes it very easy for them to produce power, and to produce tremendous power from the center of themselves. They don’t have to make a preparatory movement of taking their pelvis back, before applying great force forward.

Raz: You’re saying something very interesting. That the power comes from the ability to transition efficiently from the most power-producing initial position, to the end points. Then, how is having strong, statically contracted abdominal muscles biologically functional?

David: You have to look at the distinction between the cultural norm or aesthetic and what is functional. What is ideal from a functional point of view, and what is ideal from a cultural aesthetic point of view. And I think that something like core strengthening is linked to the idea of what’s culturally perceived as ideal, which is very different from what facilitates movement.

Raz: A workshop participant is interested in what happens when there is a loss of the lumbar curve and how it relates to peripheral nerve problems.

David: As Feldenkrais® practitioners it is important for us to understand the effect of the loss of the lumbar curve or lumbar lordosis. It causes excessive pressure on the anterior portion of the discs that are between the vertebrae. When we are young, these discs are very thick, so for a while, we can get away with this compression. But that’s not the problem. The problem is that the discs are semi-viscous, and they have a structure that keeps everything contained. When there’s anterior pressure over a long period of time, the disc gets pushed backwards and deformed. And what happens to be there, behind the vertebra, are nerve roots coming out of the spinal cord. These lumbar plexi that come out of the spinal cord feed the legs. And when they are irritated by pressure, the person can experience neuropathy. There are different causes for loss of sensation. You can have a lack of sensation for vascular reasons or because of diabetes. You can have a neuropathy in your feet because of long standing disc problems, which you might not even experience in your lower back. The discs do not need to herniate for there to be a problem. Herniation means there’s a break in the disc, and that discal matter exudes. That’s a very serious situation. More often, 90% of the time, the disc is being pushed back, causing inter-tissue pressure on the nerve root. I think this is what causes most “sciatica” or referred pain. I studied for a while with Dr. James Cyraix,

an orthopedic surgeon, from whom I gained a lot of insights. He said, and I agree, that when we experience referred pain, where we feel the discomfort is not necessarily related to where the problem is, it has to do with the extent of irritation of the tissue; the way in which the nerve root is being inflamed. The more inflamed or irritated the nerve root is, the more likely you’re going to feel the discomfort far from the actual site of the problem, for example, as far as the foot. When the lumbar curve is diminished, there is a greater likelihood of the disc being pushed back and irritating the nerve root. As a Feldenkrais practitioner, you have effective tools and can help those people. It may not be immediate relief, but you have the tools to help them recover. It’s the same issue in the cervical spine, with exactly the same biomechanical dynamics. One of my students was experiencing intense referred pain in her neck and arm. Her cervical curve was gone; her neck was completely straight. Is this somebody who might benefit from those pecking movements? I suggested that she lie on her back, and do certain things arching her neck, and moving her head and neck in such a way as to integrate it with the congruent movements of the spine and her pelvis. She sat up and her pain was almost completely diminished.

Raz: What about someone who has a difficulty in rounding their back. There are types of scoliosis in which there is an exaggerated lumbar curve and a restriction in being able to tilt the pelvis backwards. Sometimes those exaggerated curves are being stabilized by a Harrington rod, so then of course, there’s no movement between the vertebrae.

David: Or, cerebral palsy. I have worked with people for whom the posterior tilting was difficult. But, I’ve never seen anyone whose pain was connected to their inability to tilt their pelvis posteriorly. The nerve roots which get perturbed are behind, not in front. I’m not making a case that the only movement that matters is to be able to anteriorly tilt our pelvis. We need to be able to round our back in order to come up. We need to be able to shorten our spine, in order to lengthen it. In tai chi, it is said, “If you want to go to the left, you have to go to the right first.” And that’s so brilliant. If you want to go up, you need to go down first. That’s such a fundamental understanding. When a person’s spinal mobility is limited by major surgical intervention, like a Harrington rod, you can help them maintain the mobility and length that is possible, without challenging the fusions or attachments.

Raz: Going back to the orientation of the head in your FI demonstrations; in addition to the pecking movement that came at the end, we had rolling the head versus lateral bending of the head. You were connecting it to the general organization of shifting weight. And you talked about how turning the head to one side tonifies or organizes the entire organization in relation to the shifting of weight. One of the questions was, is it

accurate to say that when I’m sitting and turning to look to the left, or turning to look to the right, that this action is tonifying the musculature on the side to which I’m looking?

David: A well-organized person, with their head in the middle, and their torso and legs square to the ground, will experience global change in their tonus upon turning the head. Now, the extraordinary thing is, if I turn my head to the right, it’s the right side of my neck that is de-tonifying in the front. The left side of my neck tonifies in order to control the turning. Control of the turning is happening through the sternocleidomastoid and related muscles on the left side, on the opposite side, which is counter intuitive. A well-organized person doesn’t turn their head independently. A person who turns effectively, turns their spine, chest, shoulders; their whole self. With C6 on top of C7, there’s a lot of differentiation in the movement of the head, a lot of differentiation possible relative to the torso. The precision and delicacy of the movements of the head and neck are a hallmark of human development. Moshe uses this in many ATM lessons. You’ll see that there are many lessons where you’re being asked to fix much of yourself in one position, while keeping your head and neck free to move.

Raz: Here is a new question. We watched a video of you giving an interesting lesson to your daughter, Ariella. I’m referring to the one where you had her lie on many rollers that were gradually wider in diameter from the sacrum, up to the upper back, and the head. Two questions related to that situation: Why did you create the width gradation of the rollers? And why didn’t you take many rollers of the same diameter, so that her spine would be parallel to the table?

David: Because with that gradation, I’m able to have the pelvis lower, or behind the torso. And ultimately, I can have the head arched and behind the thoracic spine, the torso. If the person can conform to the shape of this environment, it allows for an effective arching of the whole self, from the hands and arms all the way down to the pelvis and legs.

Raz: Someone asks: Is there a way to tell—before putting someone in that position—whether they would be able to conform to this situation, or not? Do you have a way to assess if their back is kyphotic, or if this way of working would be too much?

David: I think of it as a series of graded lessons. If you watch the video of the workshop, you’ll see that is how I was working. I believe in the second or third lesson with Morgan, I did something where I left the roller behind her pelvis, and then I put a very large six inch roller behind her upper back. [Fig 4] That requires the thoracic spine to come toward concavity, which contradicts the normal convexity of the thoracic spine.

So, over a period of six to eight FI lessons, we have gone—in many small steps—from simplicity to complexity.

Raz: We have some questions about the general structure of a Functional Integration lesson. You made a distinction between the classic strategy of joining the person and their pattern, versus some of what you were doing in this workshop, where you were leading the person more actively into unfamiliar patterns. How do you create a coherent picture from your explorations? Because you were doing this at the same time as you were raising different hypotheses and trying to disprove them.