Feldenkrais

™ The

#32 Listening Journal

2020–2022

Cover Marina Rosenfeld, Deathstar, exhibition poster, 2017

Deathstar, the title of Marina Rosenfeld’s solo exhibition at Portikus (Frankfurt, Feb 17-April 16, 2017), referred to an unrealized line of research conducted in the late nineties in the last days of the sound laboratory at AT&T (formerly Bell Labs). Rosenfeld reconstructed a multi-microphone array associated with "perceptual soundfield reconstruction," that is, a recording technique that aimed to reproduce a vivid, dimensional and experiential account of one acoustic space within another. For the artist, the "deathstar," the abandoned device's informal nickname, pointed to an intriguing alternative technological future where a potentially non-linear, decentered subjectivity, tied to difference and the particularities of bodies, might have supplanted the coming emphasis on portability and standardization that fed into the rise of the cell phone. For the work, Rosenfeld took up the deathstar’s idea of environmental recording but inserted it back into a more immediate and complex temporality, that of the gallery, which was co-opted as a site of continuous, simultaneous recording and playback for the twomonth duration of the exhibition. An audio score consisting of extended “silences” punctuated by vocal utterances, noise and brief eruptions of electro-acoustic sound, was emitted at floor level, where it co-mingled with environmental noises (geese, visitors, traffic, bells) and entered the

system via the microphone array high overhead.

From Donaueschinger Musiktage festival book

Letter from the Editor 5

26 A Refinement of Weber’s Law Mercedes von Deck 34 The Advantages and Disadvantages of a Diagnosis: The Case of Yuval Michal Ritter 39 On Listening David Kaetz 42 At the Piano: The Hidden Physical Component in Listening Alan Fraser 71 Back to Back Breathing Alice Friedman 75 Two Senses of Hearing David Kaetz Contents

78 Leftovers / The Orienting Stone D. Graham Burnett 87 Learning to Listen, Learning to Hear Maggy Burrowes 97 On the Primacy of Hearing Moshe Feldenkrais 102 The Nature of Singing: A Conversation Deborah Bowes, Karen Clark, Richard Corbeil, Drew Minter, Stephen Paparo, Robert Sussuma, and Kwan Wong 118 Contributor Bios

The Feldenkrais® Journal 2020–2022

3

A case study of Gabriel Mata and his recovery from the West Nile virus using the Feldenkrais Method® Daniela Schellenberg 12 How the Feldenkrais Method® of Somatic Education Helped Me to Control My Rage Mark Snyder 19 Learning to Teach the Feldenkrais Method® Online and Outside David Hall Fritha Pengelly Fariya Doctor

© Copyright 2022 Feldenkrais Guild of North America. All rights revert to authors and artists upon publication.

Letter from the Editor

Editors of The Feldenkrais Journal ™ often wonder whether a themed or general issue would better suit the interests of our readers. Based on the quality and breadth of the submissions we received we opted for a hybrid format this time, publishing research and case studies alongside contributions with the theme of "listening." Fortuitously, this theme allows us to listen, metaphorically, to its echoes in the general pieces as well. Indeed, Dr. Feldenkrais himself did not often address "listening" explicitly. And yet his article, "On the Primacy of Hearing," first published in 1979 in Somatics magazine, suggests the broad view that we attend to the resonance of this theme throughout the method.

We start this issue with several articles that highlight the value of what we could call a metaphorical listening or attention. “A case study of Gabriel Mata and his recovery from the West Nile virus" is Daniela Schellenberg’s moving account of how one client listened to his potential and made unanticipated progress as a result. In "How the Feldenkrais Method® of Somatic Education Helped Me to Control My Rage" Mark Snyder applies close listening skills learned in Functional Integration® and Awareness Through Movement® lessons to his behavioral challenges.

For “Learning to Teach the Feldenkrais Method Online and Outside,” David Hall, Fritha Pengelly, and Fariya Doctor attend to the potential resonance of high and low-tech options for staying connected (wait till you see what these practitioners have rigged up!). In "A Refinement of Weber’s Law" Dr. Mercedes von Deck unpacks recent research into why listening takes time. We are blessed with the benefit of her expertise. Michal Ritter’s empathic listening propels “The Advantages and Disadvantages of a Diagnosis: The Case of Yuval," as she questions who we listen to and why.

David Kaetz, an erudite Feldenkrais® practitioner, musician, and poet, has generously adapted the foreword to his book Listening with Your Whole Body to start off the second half of this issue. There isn’t a better story or storyteller. The following contributions engage the theme of "listening" in the Feldenkrais Method explicitly, accompanied by vivid illustrations.

Alan Fraser’s “At the Piano: The Hidden Physical Component in Listening" presents a rigorous and yet accessible piano playing technique. This entry will bring out the musician, not to mention the child, in every practitioner. Maggy Burrowes is at the mic in “Learning to Listen, Learning to Hear,” gracefully blending insight on singing and healing in a roman à clef to which we can all relate.

Between these two musical pieces, Alice Friedman, an assistant trainer and former dancer, has choreographed a beautiful Feldenkrais

3 The

Journal #32 Listening

Feldenkrais

lesson called "Back to Back Breathing." Friedman brings new meaning to our familiar “feedback mechanism” of the floor, inviting trainees to lie on their sides, backs touching, listening to each other breathe.

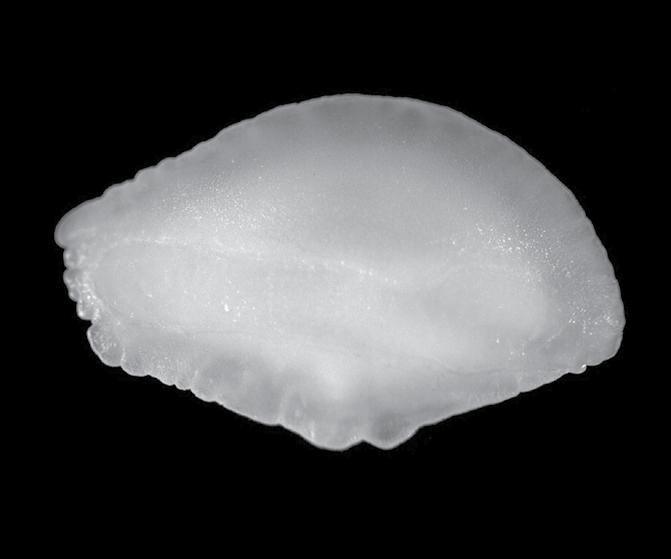

David Kaetz’s second contribution to this issue, "Two Senses of Hearing" weaves together unexpected stories and histories that prepare us for D. Graham Burnett’s “Leftovers / The Orienting Stone,” a rich evolutionary perspective on the relationship between hearing and navigating space.

Which brings us to Moshe Feldenkrais “On the Primacy of Hearing," the heart of this issue of the Journal. It would take a whole Feldenkrais training to identify the various threads in the piece. In one turn not otherwise explored in the issue, Dr. Feldenkrais ties the arrested development of our hearing to the overreach of our vision, which he describes as having become “domineering instead of dominant.” As in other texts published and republished here, there is a lesson at the end inviting readers to experiment with their eyes closed.

Deborah Bowes, Karen Clark, Richard Corbeil, Drew Minter, Stephen Paparo, and Robert Sussuma wrap the issue in a conversation on "The Nature of Singing," a workshop series organized by Kwan Wong that has twice featured these dynamic practitioners, in 2020 and 2021.

The last few years have provided ample opportunity to apply what we have learned in Feldenkrais training and practice. The Covid pandemic, social inequity, and global conflict have called for bold action. But they also have called for us, collectively, to cultivate listening—both metaphorically and actually—with our whole selves.

—Helen Miller

4 2020–2022

A case study of Gabriel Mata and his recovery from the West Nile virus using the Feldenkrais Method® of somatic education

I trained as a Sport Kinesiology and Human Movement Science teacher in Switzerland, exploring many different sports and athletic activities. During my studies, I suffered a serious back and neck injury and was told by doctors that I would not be able to return to sports or teaching. Luckily, the massage therapist I worked with in the hospital was studying the Feldenkrais Method and introduced me to a community of practitioners. Inspired by their approach, I entered a training program and became a Guild Certified Feldenkrais PractitionerCM , a life-changing experience that has helped me recover from my injuries. I entered the profession formally and soon opened my own practice helping others to recover and regain function.

Years later, I had the opportunity to work as an independent consultant at a pain clinic where I met Gabriel Mata. Mr. Mata’s willingness to learn and his curiosity were immediately apparent and proffered a chance I could help him. This is the story of how we started

5 The Feldenkrais Journal #32 Listening

Daniela Schellenberg

working together and, over a period of two years, made significant improvement in his ability to recover movement and function.

Introduction

Gabriel Mata is a 53-year-old male from Desert Hot Springs, California who presented with chronic pain secondary to a mosquito-transmitted virus called the West Nile virus. He was bitten and became infected with the West Nile virus on or about July 3, 2015, at the age of 50 years. During the infection, he felt very weak and had influenza-like symptoms, including chills and diarrhea, loss of balance, sleeplessness, dizziness, and blackouts.

On July 7, he had a seizure that preceded a coma which lasted two days. When he awoke, he could not move his legs and arms. He then lapsed into another coma for ten days. He was taken to two different hospitals over a period of eight weeks.

Because the doctors could not diagnose the etiology of his signs and symptoms, Mr. Mata was taken to a specialty clinic. When he awoke from the coma, he had feeling in his legs but could not move them. His weight fell quickly from 82 to 64 kg (180 to 140 lb).

Mr. Mata experienced severe pain in his hips and pelvis, which radiated down both legs, and also felt tingling in his toes. At the specialty clinic he received individual physical therapy. He was brought to the intensive care unit where three times per day doctors performed lumbar punctures, also known as spinal taps, during which a needle is inserted between two lumbar vertebrae to remove a sample of cerebrospinal fluid.

Mr. Mata exhibited both pain and paresthesia, a burning or prickling sensation, in the lower parts of both legs. He had no muscle strength in the left lower leg, severe soft tissue swelling in both feet, and Sudeck’s atrophy, a disturbance in the parasympathetic nervous system, in his left leg. The bones in his left leg were weaker than normal, and bony changes were present. The intensity of his pain ranged from moderate to severe and was worsening. He was treated with medications and regular physical therapy.

When Mr. Mata was discharged he had to continue using a wheelchair, and neither his home therapy nor the physical therapy in the regional hospital appeared to help his condition significantly. Staff at the regional hospital referred him to a local pain clinic with a multidisciplinary treatment plan that included the Feldenkrais Method. I informed Mr. Mata that the Feldenkrais Method was likely to be effective but would require substantial time and commitment. He responded positively to my caution, and we began.

6 2020–2022

Process

In January 2016, Mr. Mata started Feldenkrais® lessons with me. He had been employed in industrial construction and painting, and liked to ride his bicycle. Taking his interests and background into account, I tested his righting reflexes and lifted him up during the first lesson to check his ability to use ground forces in standing. He was amazed that he could feel the blood rushing to his legs and feet during the two seconds of standing. This encouraged him immediately and helped him to believe that it would be possible to improve significantly.

Many patients with paresthesia do not realize how much they can actually do through visualization. This was the case with Mr. Mata. The idea that a little mosquito had taken his life like this made him feel depressed at times. He felt sad, stuck, and somewhat humiliated, especially in his hometown where he had regularly ridden his bike to work. Because doctors told him that he had to accept his situation, that there was nothing he could do about it, he felt like he had no other choice. He was too weak to go anywhere else at that time other than to his doctor appointments and to the hospital for therapy.

At the beginning of our work together it was difficult for Mr. Mata to do most everyday activities, such as going to the bathroom or getting onto the floor and back into his wheelchair. Because he had been able to stand for a second on his right leg, feeling the ground forces, I decided to have him get on a stationary bike each time he came to the lessons, using his arms to get on the bike and then pushing the legs down to regain strength and stimulate his feet. His motivation and discipline were unbelievable.

With this activity, Mr. Mata experienced the powerful effects of his own willpower, and that a lot might be possible. Rather than being in a state of hopelessness and apathy, he became engaged, enthusiastic, and a rush of energy was visible on his flushed cheeks. Mr. Mata was already a very positive person, with a lot of faith and a great sense of gratitude, which helped him in the whole recovery process.

During the individual Functional Integration® lessons we did substantial foot and toe work, stimulating the brain to recognize the feet and connect them to the pelvis and spine from below. I had Mr. Mata roll and crawl a lot, and reconnect to his locomotion. I gave him resistance to push against when necessary, and had him tuck his toes under in lying in order to practice pushing from his feet.

I showed Mr. Mata what he could do using past experiences, images, and a broader idea of functioning such as looking up to engage his back muscles and looking behind at his foot. We explored distal motor control of the feet and hands and also leveraged a proximal approach to reactivating toe, foot, ankle, finger, hand, and wrist movements from the core or center. We coordinated the movement of his eyes with visual cues and the recollection of past experiences, stimulating efferent

7 The Feldenkrais Journal #32 Listening

neurons and motor neurons that carry neural impulses away from the central nervous system towards muscles in the pelvis and down into the legs and feet.

Before asking him to use his lower legs, in which he reported decreased sensation, I decided to help Mr. Mata develop a clear sense of the movement possible in his knees, which he reported feeling more clearly, connecting them to his pelvis and core while engaging his upper body. Eventually he was able to kneel in front of the table, using his upper body and arms to help bear his weight while upright in various positions: standing on his knees, shifting his weight, leaning, and turning. By using his better side and visualizing how he could apply what he learned and remembered from the right, he was able to stimulate his left side and regain sensation little by little.

During the Awareness Through Movement® classes, Mr. Mata took advantage of a number of opportunities to move more. He crawled, rolled, pushed up, used his core diagonally with hands on the feet or lying on a roller. He used his hip and back muscles to extend and his head to orient himself in space in a prone position. Gradually he was able to push himself up through the feet and hands. Mr. Mata learned how to sit on his heels and squat and how to stand up from a squatting position. Eventually he balanced on a big gymnastic ball while sitting and also while lying over it, kneeling on hands and knees. It was not easy for him, yet we stimulated the deeper spinal muscles in many different ways, working with the ball and other wobbling objects such as a roller and a balance disc. In class he was always willing to try, sometimes with my help, often employing his own efforts. In fact, Mr. Mata frequently showed off, expressing his pride and sense of accomplishment and engaging others around him.

As we worked, using the Feldenkrais Method of somatic education and other alternative therapies, Mr. Mata appeared more and more inspired to keep going. His hope and newfound freedom were palpable. He said he felt understood and supported by me and my colleagues. He said that seeing other people with even worse conditions was also motivating. Over time, his spirit brightened. He told me he felt more alive and did not feel so sorry for himself anymore.

Mr. Mata responded positively to assistance at every stage and each success increased his motivation. In multiple ways Mr. Mata stimulated his nervous system to recognize the function that had been there previously. He moved better every day through awareness and practice. He relearned to move every part of himself, even when movement seemed lost forever. Mr. Mata got stronger and stronger, embracing memory and discovery to “make the impossible possible.”

Towards the end of our intensive work together, Gabriel said to me:

I feel like a person again, like a human being. When I go to the bathroom to urinate, I feel like a man again. There is nothing

8 2020–2022

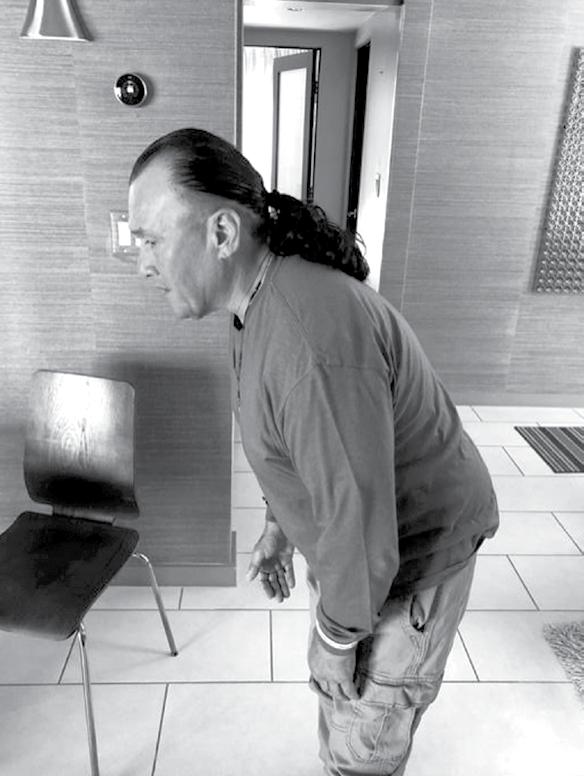

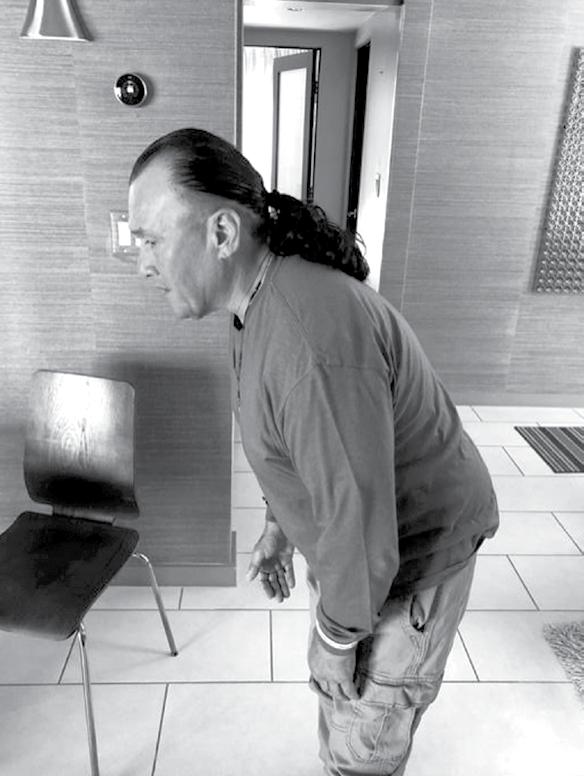

Fig 1 Gabriel Mata standing up from a chair without help after being in a wheelchair for three years (2018)

9 The Feldenkrais Journal #32 Listening

stopping me. The Feldenkrais Method has helped me stand up. Every little muscle in the body remembers, like when you were a child, a baby, when you learned all the movements. It’s all in the mind. It taught me that anything is possible with willpower and knowledge and wanting to stay alive and wanting to live. Life is beautiful.”

Results

In August 2017, two years after the initial arbovirus infection, Mr. Mata stood up by himself at the counter of the pain clinic, using what he learned from all the weight-bearing movements on the floor, in sitting, and on his hands and knees. [Fig 1] His improvements gave him confidence and motivated him to continue to learn and improve. Once he had sensation in his legs, he felt renewed purpose and possibilities for his life.

With diligence and discipline and sticking to his home therapy program like squatting, balancing on one leg, weight shifting, rolling from side to side, sitting on the heels, and working with his toes and feet, he got inspired. “Every day I wake up and have something to do. I get to meet the therapists and learn and regain strength and confidence. It gives me a meaning and a goal in my mind. I could never tell myself I did not at least try and give it a chance. And it worked!” he said.

Indeed, he put a lot of work into it. His mantra became, “It works if you work it.” Because of his positive attitude, we all got inspired, all the therapists and other patients. Mr. Mata was so excited during Functional Integration sessions when he was able to wiggle his toes or when he felt a muscle firing in his thigh, dormant for so long. He made us all cry when he got up the first time in class or in front of the medical doctor when he showed him how he could walk with the crutches. One day, when he had to make his schedule, he just stood up from his wheelchair in front of the main desk; everyone was blown away not expecting him to stand up. What a surprise! It seemed to affect other patients too in the sense that the collective struggle seemed lessened after seeing Mr. Mata improve that much.

He had been told by doctors that he would be paraplegic and dependent on caregivers for the rest of his life. Instead, he was experiencing a significant improvement of his functionality, in the middle of a promising journey. “One day, I will show other people and talk in front of other people, to help others,” Gabriel said.

Through Gabriel’s work with the Feldenkrais Method, he has seen the many ways he can help himself. He has learned the principles of the Feldenkrais Method, which have helped him to take care of himself in many situations that had previously been difficult or impossible to tolerate. For example, he has fallen many times in many places, such as in the bathroom and in the shower. He learned how to roll when he fell

10 2020–2022

without hurting himself, how to be agile when he hurt his ankle, and how to use proper posture in balancing and weight shifting for walking. Most of all, he learned how to keep his positive mind, and to remain motivated by his success, his hard work, and by therapists who challenged him and offered him insight and support. As a result, he continued to improve steadily and get on with his life.

Mr. Mata responded very well to his process with the Feldenkrais Method and somatic learning. He is walking with crutches after three years and continuing to improve strength in his legs and coordination, especially on the left side. The right-side leg function has improved from virtually nil to 80%, and the left side from virtually nil to 50%.

His left stabilizing core muscles, dorsiflexion, and toe curling on the left foot, and knee extension and stability on standing, are still weak. The left hip muscles and muscles around the knee are relatively atrophied but are getting stronger and more innervated. His lower back pain from the lumbar punctures was treated with cortisone injections, which have helped. He has applied movements from Awareness Through Movement classes to end his back pain, using “the pelvic clock”, “oscillations through the body”, “sitting on the heels” and many more related lessons. He can balance on the right leg for about 20 seconds with eyes open, and on the left leg he can balance with the crutches for about two seconds. His left gluteus-muscle strength is about half of that on the right side. For longer distances he still uses a wheelchair, but for short distances or going out to a restaurant he uses crutches.

Due to Mr. Mata relying more on his right side and right leg, which have recovered more quickly, he is favoring this side. The left side is still much weaker. Doctors have assessed that the West Nile virus is still present in his left leg but localized in that leg and inactive. This might contribute to why the left side is slower to recover in comparison to the right leg. Nevertheless, the signs are encouraging that with time Mr. Mata will regain more coordination and strength on the left side and eventually walk unaided or with one crutch. According to Mr. Mata, his neurologist was most impressed that he has been able to regain the function of walking.

Conclusion

By working with the somatic learning approach of the Feldenkrais Method, Mr. Mata has regained partial leg and gait function after being in a coma for 12 days with no leg function. After three years of being in a wheelchair and not being able to stand up or walk, he is able to stand freely, weight shift, and walk with crutches. He is continuing to make improvements on a weekly basis by consistently practicing everything he has learned. His goal is to drive a car again, which seems realistic considering his determination and what his recovery and progress have shown so far.

11 The Feldenkrais Journal #32 Listening

How the Feldenkrais Method® of Somatic Education Helped Me to Control My Rage

1 Feldenkrais, Moshe. Body Awareness as Healing Therapy: The Case of Nora (Berkeley: Somatic Resources Frog, Ltd., 1977).

2 Body and Mature Behavior: A Study of Anxiety, Sex, Gravitation and Learning (New York: International Universities Press, Inc., 1949).

Over the past few years I suffered a series of rage reactions or tantrums triggered by events connected with the sale of my parents’ home in 2015. These reactions were worse than any I had previously and gave me pause. For some time I felt helpless to change my behavior, but I have made progress using what I learned from the Feldenkrais Method of somatic education. I would like to share some of my observations in the hope that others with similar problems might benefit.

I am not a Feldenkrais® Practitioner, nor have I received any professional Feldenkrais training. Most of what I learned about Feldenkrais I learned from the late Deedee Eisenberg of Califon, New Jersey, through her series of Awareness Through Movement® (ATM®) classes and ten Functional Integration® (FI®) sessions in 2002-2003. After these sessions ended, I read a few of Dr. Feldenkrais’ books. The Case of Nora and Body and Mature Behavior left the most lasting impressions.1, 2 In 2015 I had another ten FI sessions with Michal Ben-Reuven of Princeton, New Jersey, to help with a gait issue. I felt like I needed to learn how to walk better because my hip joints often became sore. The lessons cured the soreness.

12 2020–2022

Mark Snyder

My interest in bodywork was motivated by lower back pain that started in high school. It would come and go without apparent reason and wasn’t a problem until I started working. I would get spasms that sometimes prevented me from walking, as well as neck pain and stiffness. I tried a number of approaches, including Trager®, chiropractic, and Rolfing®, without lasting relief. Only after my fifth session with Deedee did I sense a reliable shift. Since then I have been relatively pain free, even when doing strenuous work like house-moving. When I feel something is not right, I apply what I learned from Deedee.

The following procedure summarizes what Deedee taught me in working with my back: First, pause and respect the pain, as it is a form of information. Second, explore the movement in slow motion to find the earliest discomfort. Stop at the first hint of discomfort and go back to neutral. Try this a few times and notice what you feel. I call these, “baby steps.” Finally, try the movement again. After two or three “baby steps” I can usually resume activity without pain or worry.

I started out employing these steps with my back, but I have learned to apply them to other parts of my body as well, such as my knees, ankles, and neck. As I will discuss in some depth with this article, the process has also helped me to manage my rage.

Losing my temper had been a persistent if infrequent occurrence for most of my life. It got much worse leading up to and after the sale of my parents’ house. Although I had seen other people behaving in a similar way, some claiming satisfaction as a result, I finally accepted that losing control of my anger was not healthy for me. My reactions to frustrating situations were consuming. Fortunately, I never directed my outbursts at another person; instead, I attacked the objects around me and broke my things.

In the summer of 2016, looking forward to visiting my Uncle Don in North Carolina, I decided to clean out the back of my minivan. It was late afternoon. I thought it would be a twenty minute job, after which I would cook something on the grill, and enjoy a small sense of accomplishment.

I thought the rear hatch was unlocked so I went to the handle and pulled, but it did not open. I unlocked it from the driver’s door and tried again. No luck. I wondered if the latch had gotten loose, something I had fixed the year before. No, there was no play in the latch. I tried unlocking it again. Nothing. I locked it and unlocked it a few more times, pulling the handle, pacing between the door and the hatch. Nope. Using my keychain, I did it again, watching the lock button through the rear windshield. The button went up and down, but it didn’t matter. “Dammit!”

“This shouldn’t be happening!” I thought. “The latch got loose, but I fixed that!” I tried to remember what the hatch looked like inside, but the image was foggy. “Those goddamned engineers think they are so perfect! Why didn’t they figure out a way to prevent this? I need to open

13 The Feldenkrais Journal #32 Listening

that hatch!” I punched and kicked the hatch a few times, denting it. “Damn those engineers! Some cheap little plastic part broke, and now I can’t use my van.”

By now the sun had set and it was getting dark. I could no longer make out the button through the window. I could feel my face on fire, my ears steaming. “Why won’t you open for me?!” I pleaded. I wanted to break something, anything. I kicked a tire, and went inside, slamming doors as I went. I collapsed in my chair in the twilight, no longer hungry, my plans shattered.

I felt like a rock, stuck in place. I was humiliated and ashamed. A weight pressed on my chest; it took effort to breathe. I felt paralyzed. After a little while it became difficult to keep my eyes open. Before I realized, it was past ten o’clock. Defeated and humiliated, I went to bed and slept for a long time, a hard sleep.

I did not feel much different the next afternoon when I finally woke up. I was not hungry. I did not want to move, but I made myself eat, watch TV, and clean up the kitchen to make the time pass. I tried to read, but could not. I was a zombie for about twenty-four hours.

Flying into a rage in front of my condo was embarrassing enough, but the rage-induced hangover was what really impaired my functioning. The blow up might last, at most, 45 minutes, but the shame and humiliation overwhelmed me for hours, even days. In that state I had difficulty performing simple acts of daily living such as eating or cleaning. I often surrendered to sleep instead. I feared I would explode and break something I needed, or just stay frozen. How could I stop repeating this pattern?

My first steps in taking control of my behavior were two small changes in my thinking, both inspired by the Feldenkrais Method. Neither of them were conscious at first. It was only as I tried to articulate what I was feeling that I was able to piece together an explanation. I asked myself questions and felt for answers, finally putting them into words.

First, I realized I could no longer convince myself that my frustration was normal. All of a sudden, losing control had become unacceptable and potentially dangerous. Just because I had never taken my anger out on anyone before did not mean I never would. If I reacted like that at work I could be fired. I did not want to be someone who lost control like that anymore. Second, I could not help but see each tantrum as a link in a long chain, each outburst having less to do with its trigger and more to do with something not right inside me. My anger was not a response to my current environment, but an unconscious reflex.

Without realizing I was applying Deedee’s (and Dr. Feldenkrais’) first step, I decided I had to pause, to interrupt my habitual pattern. Then, again without realizing it, I applied the second step she had taught me. I tried to find the earliest “discomfort.” How did this pattern start? I tried

14 2020–2022

to break down my rage. In hindsight, I realized it was my experience with the Feldenkrais Method that inspired me to approach the problem in this way: to interrupt the habit, then try to find the beginning.

My rages all started the same way, with the same thought: “This is not supposed to be happening!” The phrase acted like a switch, giving me permission to lose control.

One day in 1979, a few months into my first professional job, I came home from work very frustrated. I had been asked to work outside the scope of my education, a BA in physics, and my job of production engineer, to conduct a chemical analysis using a mass spectrometer, a task more suited to a PhD chemist. Interdepartmental politics were likely behind the scheme. Accepting the assignment would put me in the middle and set me up to fail. “This is not supposed to be happening!” I thought. “My bosses are supposed to protect me! They knew about this assignment when they hired me, but they didn’t tell me! If I refuse, they’ll let me go now. If I accept, they’ll fire me later, when I fail!” I churned my predicament over in my mind on the commute home. When I arrived I played my drums as loudly as possible, screaming at my bosses.

But it was not enough to quell my rage. I needed to break something—my drum heads, all of them. It was very hard to do. I had to stab them with the sticks, but I punctured them all. Replacing them cost nearly $100. But I felt ashamed and stupid even before I tallied up the bill. I ate dinner with my parents in silence that night.

I remembered other rage reactions I’d had, like getting stuck with my tractor in the upper field. Looking back I saw that they all ended the same way. I always felt deep shame and humiliation when the adrenaline ran out. Why, after sixty years, had I not learned?

My attitude toward this behavior changed a little as a result of these thoughts. Before, a rage reaction seemed to be one solid, unbreakable thing. Now, it had a beginning and an end. The problem had been demystified somewhat and that gave me hope.

Thinking about the broken hatch a few days later, after I calmed down, I wondered how I might have felt if I had articulated my thoughts differently. “Yes, the hatch should have a better design, but I can’t do anything about that now.” Having options in my language was like having options in my movement. I felt a distinct wave of relief that suggested I had found a crack in my wall of rage. It was in the word, “now,” the present. It allowed me to see that my rage was an escape from the present, where the hatch was locked, to a place where the hatch might be open.

And there were other cracks in the wall. Instead of being the victim of far away engineers, choosing different words had exposed me as a perpetrator of my rages. I was talking myself into them. In the moment I considered the word, “now,” I could feel my body relax. If I changed the way I talked about my frustration, could I maintain control over my anger and prevent a tantrum?

I thought, talking is a process, each word following another. This

15 The Feldenkrais Journal #32 Listening

reinforced the idea that the rage was a process, something built out of parts, steps. It was not the solid wall it appeared to be, rather it was made up of separate elements, like a differentiated movement in a Feldenkrais lesson. I felt relief upon articulating that thought. My body was giving me feedback, lifting the weight I still felt. “I am on the right track,” I remember thinking.

It was still murky. I knew I was reacting unconsciously, but the anger was so strong. What did that mean? A door is just a door, but I was acting as if it were trying to kill me. If so, why was I not afraid? “Because I was too angry,” came the response. So what was I afraid of? Oh, a bunch of things, wouldn’t you know! I might not be able to see my uncle again; he was almost 90. But that made me sad, not afraid or angry . . . .

I had bought the minivan to move all my stuff when I sold the house. If I could not use the hatch, I would not be able to move my stuff, and then what? It did not take long to remember the thought that flashed into my head around the third time I switched off the locks. If I could not use the hatch, I might have to leave my stuff behind. It would be like being homeless. Homeless! That was the big fear behind the broken hatch.

Spotting the initial fear was like noticing the earliest discomfort in a movement. Ignoring that pain and barreling through took me on a path that was different from what I wanted. Seeing the beginning gave me choices to go in other directions.

I had found and made progress with the beginning and the middle. I had found the end but I had not felt any progress. What did I know about the end? At the end was another transition, from aggression to surrender. When I gave up on the hatch I had felt only defeat and humiliation, crushed by a tiny piece of plastic I could not see. But in hindsight, there had been a ray of light. I had come back to the present and accepted that I was powerless over the door.

Giving up a losing strategy was a real victory.

Applying Feldenkrais lessons in this way changed my understanding of my rage from “something that just happened to me” to “my reaction to something that frightened me.” Even as a child playing with blocks, I had turned my fear into anger so quickly that I didn’t even remember being scared. If I could pause and acknowledge the fear, and feel it, could I interrupt my old habit enough to prevent myself from flying into a rage? Could I direct my attention to what was actually happening in the present rather than being dragged into the past or future? If I had talked myself into it, could I learn to talk myself out of it? By directing my attention consciously, rather than falling into the old rage rut, could I teach myself to behave differently? What would it be like to accept a broken car door, or office politics, as things I could not or did not have to change immediately?

16 2020–2022

As a result of this process I began to be more careful with my self-talk when I started to feel frustrated and to incorporate soothing messages whenever I felt the rage pattern being activated. Mostly by reminding myself to stay in the present, I directed my awareness to articulating and addressing the threats I was unconsciously reacting to, such as worrying about bills. I began to prioritize my day to lessen my financial threats. For example, I started spending more time earlier in the day pricing my record collection to sell. Fighting great internal resistance, I spent time working on my resume and searching job postings. These steps seemed to help. My anxiety level came down and my days brightened. I applied myself to volunteer work using my skills of writing and editing. I even got some freelance jobs. Since it was now clear that my rage reactions were triggered by things I had every right to be afraid of, like losing my job or becoming homeless, I began to understand why I was getting so upset. Facing my fears and doing something to reduce the threats made my symptoms more manageable. I was not “cured,” but I had made progress. In the months since the battle with the hatch, my progress has mostly held and even expanded, despite new threats.

I found the Feldenkrais Method to be the most effective approach to solving my long-standing back problems. The Feldenkrais Method gets to the root of the problem and provides effective tools to reestablish functional movement whenever the old habits return. I have incorporated Feldenkrais teachings into my daily routine, mostly by doing “mini-ATM sessions.” Rather than trying to force change onto my body, Feldenkrais allows me to work with my existing patterns.

As an undergraduate, I studied physics. The language of physics seeks to describe the patterns of the universe in concise mathematical statements. I searched for patterns in the Feldenkrais lessons I learned from Deedee. Then I searched for patterns in my own thoughts and emotional experiences.

Like each of my movements, each rage reaction has a beginning, middle, and end. I approached my rage as a Feldenkrais practitioner might approach physical movement. To turn the head, one must also make adjustments in the torso, the eyes, the shoulders, and the arms.

To reduce a rage, I had to address the larger threats to my well being, and break them down. I had to interrupt habitual emotional reactions and seek more functional options. I had to look at the various components of my fears and take the time to articulate and understand them.

I was still bewildered by the overwhelming shame I felt following a tantrum. Where did it come from? I noticed a strong association between loss of control and feeling ashamed. When I was out of control, I was unable to direct my attention from the present to the past and

17 The Feldenkrais Journal #32 Listening

future. I lost perspective. Not being able to control my attention seemed to be a mark of immaturity. Without accurate information gained from directed awareness, I felt less secure, internally and in terms of my place in society. Now, whenever I begin to get frustrated, I try to bring my attention to the present, ask what threats I might be facing, and allow myself to feel afraid.

18 2020–2022

Learning to Teach the Feldenkrais Method® Online and Outside

David Hall Fritha Pengelly Fariya Doctor

David Hall GCFPCM , Assistant Feldenkrais Trainer Sydney, Australia

The level of group cohesion and engagement that has evolved over the last two years of my online lessons has been amazing. I’ve been practicing the Feldenkrais Method for over thirty years and I am more inspired than ever. I cannot see myself going back to weekly “in the flesh” classes. I love the fact that I can share my screen and give students a front row view of anatomical structures or other inspiring imagery.

I have always been interested in the meditative and philosophical aspects of the work. The method as process and path. It’s not the most popular perspective and the number of people in my city who share that interest is limited. Around the world I’ve found a larger community.

I use a webcam, Zoom, Logic Pro, and the UA Apollo audio interface. I do the lesson as I deliver it using a DPA wireless microphone (experience!). The lesson I lead each week is created in the moment after immersion in the theme and preceded by an exploratory email.

Inspired by Moshe, I’ve always found recording and reviewing my lessons an invaluable source of professional development. Since May

19 The Feldenkrais Journal #32 Listening

2020 I have uploaded 124 new recordings. It’s so satisfying!

It was quite a job to get set up: the website, recording gear, and Zoom landscape all required a great deal of thought and tech savvy assistance. It has been an ongoing process of refinement that can be measured in my recordings. The thing is that you can now invest one or two thousand dollars in a set up that enables you to produce professional quality content that would have cost an arm and a leg a few decades ago.

The opportunities of this new medium for Feldenkrais® practice are endless. It’s the tactile nature of the voice that gives us the ability to create immersive educational experiences online. I'm still on a roll, creating new lessons each week, and look forward to tapping the potential for collaboration. [Fig 1]

21 The Feldenkrais Journal #32 Listening

Fig 1 David Hall in his new and improved Zoom landscape

As with most Feldenkrais practitioners I know, I transformed my practice during the pandemic. Since completing my ATM® Practicum in 2011, I had been teaching one weekly ATM class, often attended by just a handful of students. Since making the transition to online teaching in April of 2020, I am now teaching four weekly classes online with students from all over the world. After shutting down my in-person private practice in the spring of 2020, I transformed my front porch into a studio and re-opened for outdoor in-person sessions in the late summer. I’ve been successfully working with students outdoors since. The changes I’ve implemented over the past year have accelerated my learning, expanded my reach, and allowed me to continue to support my community through this time. Exploring many ATM lessons a week, teaching outdoors in a neighborhood with unpredictable elements (delivery trucks, kids playing in the pool next door, birds, heat and cold), and supporting students to develop resilience and adaptability has helped me to clarify what it means to survive in an ever changing environment, how to bring that larger context into my teaching. Additionally, teaching online has allowed me to share more responsibility for learning with my students . . . which is as it should be. [Fig 2]

22 2020–2022

Fig 2 Fritha Pengelly teaching on Zoom across from her porch studio Fritha Pengelly MFA, GCFPCM Northampton, MA

24 2020–2022

Fig 3 Fariya Doctor sustaining her Feldenkrais practice in style

Fariya Doctor B.Sc., RMT, GCFPCM Ontario, Canada

I had been teaching online for a couple of years prior to the Pandemic. When Covid hit and I had to shut down my clinic, I felt compelled to do more online teaching. My motivation was driven primarily by a feeling of isolation. Being an extrovert, I found it very hard not to see and share with people. I was grateful for my regular students showing up and we had a chance to bond and commiserate over Zoom. Thanks to online opportunities, I was also able to keep some income flowing in. Zooming has been a lifeline for me, a wonderful way for me to help people, especially those feeling disconnected or out of touch, and a vital way for me to earn a living these past two years. [Fig 3]

25 The Feldenkrais Journal #32 Listening

A Refinement of Weber’s Law

Mercedes von Deck

Weber’s Law

Dr. Feldenkrais often referred to Weber’s Law to explain his rationale for reducing effort in movement. Weber’s Law states that there is a constant ratio between the magnitude of a sensory stimulus—such as a sound, light, pressure, or muscular work—and the change in that stimulus needed to create a difference that the brain can recognize. In practical terms, if our senses are exposed to a large stimulus, a large change in the intensity of that stimulus is necessary for us to notice any difference. On the other hand, the smaller the initial sensory stimulation, the smaller the amount of change needed for us to discern a difference. Dr. Feldenkrais frequently brought up the example of a fly landing on a weight:

1 Moshe Feldenkrais, “Mind and Body,” Elizabeth Beringer, ed., Embodied Wisdom: The Collected Papers of Moshe Feldenkrais (Berkeley: Somatic Resources, 2010), 37.

2 Moshe Feldenkrais, “Learning to Learn” (1980), http://thefieldcenter. org/06resources/ downloads/learning_to_ learn.pdf

If I hold a twenty pound weight, I cannot detect a fly landing on it because the least detectable difference in the stimulus is half a pound. On the other hand, if I hold a feather, a fly landing on it makes a great difference. Obviously then, in order to be able to tell the differences in exertion one must first reduce the exertion. Finer and finer performance is possible only if the sensitivity, that is, the ability to feel the difference is improved.1

If we are unable to sense the differences between two or more ways of performing an action, we will be unable to choose an option that is more comfortable or more efficient. In his treatise "Learning to Learn" Dr. Feldenkrais stresses, “It is easier to tell differences when the effort is light. All our senses are so built that we can distinguish minute differences when our senses are only slightly stimulated.” 2 While many of us have been taught we must work harder in order to perfect a skill, proceeding with more muscular force actually makes it more difficult to feel the small changes that will allow for lasting improvement. Weber’s Law launched the field of psychophysics—the science of measuring the effects of physical stimuli on the perception of sensations in the mind of the observer. Previously, science was focused on describing the physical world. Mental activity—our consciousness,

26 2020–2022

3 The Champalimaud Foundation, funded by the Portuguese entrepreneur Antonio de Sommer Champalimaud, created this state-of-the-art research facility in 2010 to support biomedical research that can improve the quality of life of individuals around the world through preventing, diagnosing, and treating disease.

perception, thinking, judgment, emotions, and memory—appeared unquantifiable, subject to force of will and random thoughts. In the 18th century, Ernst Weber showed that it is actually possible to measure processes occuring in the brain and to use these measurements to predict how the mind will perform. As it turns out, how accurately we can sense differences in weight and pressure has nothing to do with willpower.

4 Jose L. Pardo-Vazquez et al., “The mechanistic foundation of Weber’s law,” Nature Neuroscience 22 (2019): 1493–1502, https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41593-019-0439-7

The operation of Weber’s Law, also called the Weber Fechner Principle, has been replicated in hundreds of studies over the last two centuries. The effect across all sensory modalities has been observed in many animal species. At the same time, while Weber’s Law is reproducible, it has eluded definition by mathematical models. Multiple models have been proposed, yet all have failed to accurately describe the data—until recently. In August 2019, the journal Nature Neuroscience published the work of a team of researchers from the Champalimaud Center for the Unknown in Lisbon.3 By adding in the variable of reaction time and analyzing the time it takes for rats to make a decision regarding differences in the intensity of sound, the researchers were able to derive an accurate and precise mathematical model describing the cognitive processes underlying Weber’s Law.4 Weber as well as other scientists until the Champalimaud group did not consider the time it takes to distinguish differences in sensory stimuli when they noted that the difference in size of the smallest stimulus needed to detect differences in sensation is always in the same ratio to the magnitude of the starting stimulus. By adding in reaction times, the researchers from Lisbon were able to define a mathematical equation that reproducibly describes how animals sense differences between sensory stimuli based on the magnitude of the initial stimulus, no matter how small or large the stimulus. The research group emphasizes that the time it takes to sense differences is key to understanding how the brain processes sensation.

The History of Weber’s Law

5 Dennis Leri, “The Fechner Weber Principle,” 1997, Mental Furniture #10, Semiophysics, accessed November 1, 2022, http:// www.semiophysics.com/ SemioPhysics_Articles_ mental_10.html

6 Moshe Feldenkrais, Body and Mature Behavior: A Study of Anxiety, Sex, Gravitation and Learning (Berkeley: Somatic Resources, 2005), 147.

Ernst Heinrich Weber (1795-1878), for whom Weber’s Law is named, was a German physiologist and anatomist. He was interested in how people sense differences between varying amounts of sensory input, and studied the perception of weight, temperature, and pressure. In his research, Weber discovered that the minimum difference required to discern between two similar stimuli is proportional to the magnitude of the original stimulus.5 In other words, if the original stimulus increases, the magnitude of the difference between the stimuli required to sense the difference does too. Below the threshold of the smallest perceptible difference, no difference will be noticed; for instance, to identify the stronger of two pressure-stimuli applied to the skin, one must be at least 12% more intense than the other. For weight, the ratio is 1/20 to 1/40.6 If you have ever tried to compare the weights of melons in the grocery

27 The Feldenkrais Journal #32 Listening

7 Leri, ““The Fechner Weber Principle”.

store and have wondered why it is so hard to tell the difference by holding one in each hand, Weber’s Law has the explanation. If one melon weighs six pounds, the other melon must weigh about five ounces more or less for most people to tell the difference. This amount is the smallest detectable difference. A difference of a quarter pound, or four ounces, for example, would not be appreciated.

8 Feldenkrais, Body and Mature Behavior, 147.

Another German physicist and philosopher, Gustav Theodor Fechner (1801-1887), furthered Weber’s work by inventing a unit of just noticeable differences (JND) and measuring sensation in terms of this unit. He explored touch and weight as well as visual acuity and brightness. Fechner confirmed that just noticeable differences were proportional to the size of the starting stimuli; furthermore, smaller differences can be appreciated more clearly when the starting stimuli is small. Fechner wanted to establish an exact relationship between a physical stimulus and the mind’s perception of that stimulus in order to quantify behavior. He tried to formulate an equation that could mathematically characterize the relationship between physical stimulation, the sensation of the stimulation, and the recognition in the brain of the stimulation.7 Since logarithmic scales represent the percentage of change, he determined that S = k log R where S is the intensity of sensation and increases exponentially in relation to the stimulus (R) where the constant k varies depending on the sense being tested.8 This equation seeks to quantify the nervous system’s ability to sense a change in each sensory stimulus as a proportion of the starting stimulus. If there are 100 x 100 watt lights in an indoor amphitheater and one burns out, spectators watching the game won’t notice. If there are ten lights and one burns out, this is beginning to approach the just noticeable difference. If there are five lights in the same size space, turning off one will be immediately apparent.

9 Myrl Cowdrick, “The Weber-Fechner Law and Sanford’s Weight Experiment,” The American Journal of Psychology 28, no. 4 (1917): 585–588, https://www.jstor.org/ stable/1413900

Fechner’s equation above was later shown to be only approximately true and to work best in the mid range of stimulus. Not all the measured data fit his equation.9 The key point is that he realized that our perception of physical events could be represented in a reproducible manner in the brain. His work advanced the field of psychophysics, making unseen mental activity available to scientific measurement.

Weber’s Law, also called the Weber Fechner Principle in honor of both men, continues to be understood intuitively and measured in terms of ratios, yet no mathematical model has been able to completely explain the law up until now. Finding a mathematical model has important implications for how the brain makes comparisons between two similar sensory experiences. A precise model of Weber’s Law could help us determine how the brain interprets differences and how perception works.

28 2020–2022

10 “Transduction” in Sensory Processes, Boundless Biology, Lumen (n.d.), accessed November 1, 2022, https://courses. lumenlearning.com/ boundless-biology/chapter/ sensory-processes

The Science of Weber’s Law

Weber and Fechner showed us that the human brain can tell differences between differing magnitudes of sensation as a proportion of the starting stimulus. Other scientists later confirmed the same phenomenon in other species. How might our knowledge of the brain and nervous system help explain the observations described by Weber’s Law? In turn, can Weber’s Law lead to better understanding of how sensory information is processed by the brain?

A sensory stimulus causes the sensory receptors in our skin, eyes, ears, nose, or tongue to fire and send nerve impulses, or action potentials of electrical activity, along the sensory nerve to the spinal cord and brain. Sensory receptors communicate the size of the sensory stimulus through two different mechanisms: increasing how fast the nerve impulses are sent (the firing rate), and increasing how many receptors are activated. A more intense stimulus initiates faster firing of more nerve impulses in more sensory receptors.10

The integration of sensory information begins as soon as the information is received in the central nervous system. How the brain translates this data into perception is largely unknown. Research building on Weber’s Law by the Champalimaud Center for the Unknown in Lisbon might provide a key. Mental processes previously considered unmeasurable, such as sensations and thoughts, may be usefully measured.

Knowing how perception occurs in the brain could have important implications for the treatment of disorders of perception such as hearing loss, vision loss, or loss of proprioception, which can lead to difficulties with balance. While these disorders can originate at the level of the sensory organ, they can also occur centrally in the brain. We don’t know if each sense receptor is mapped to its own neuron in the brain or whether the impulses activate wider networks of neurons. If we can better understand perception, perhaps we can find a way to improve the connection between our sense organs and our brains, or activate larger or different areas of the brain when a deficit occurs. This concept of neuroplasticity suggests that healthy parts of the brain can take over the function of injured or malfunctioning parts.

As discussed, it is easier to feel differences when the starting stimulus is smaller. The brain seems to be able to discern the addition of a few more receptors when there are small numbers of receptors firing in the first place, but we cannot tell if a few more receptors are added when there are a large number of receptors firing to begin with. What is happening in the brain to make this true?

Many models of neuron operation in the brain have been previously proposed to describe Weber’s Law. Before the recent discovery by the Champalimaud Center for the Unknown research group, none were entirely successful. Most older models tried to use Signal Detection

29 The Feldenkrais Journal #32 Listening

11 Joshua I. Gold and Takeo Watanabe, “Perceptual learning,” Current Biology 20, no. 2 (January 2010): 46–48, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. cub.2009.10.066

12 Stephen W. Link, “Psychophysical Theory and Laws, History of,” International Encyclopaedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences vol. 19, 2nd edition, ed. James D. Wright, (Oxford: Elsevier, 2015), 470–476.

13 Stephen Link, “Fechner’s Pillars: Contributions to Hypothesis Testing, Statistics, Psychoanalysis, and Cognition,” (2001), accessed November 1, 2022, http://psychologie. biphaps.uni-leipzig.de/ fechner/generalinfo/PDFs/ SLink.pdf

14 Lester E. Krueger, “Reconciling Fechner and Stevens: Toward a unified psychophysical law,” Behavioral and Brain Sciences 12, no. 2 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989): 251–320, https://doi.org/10.1017/ S0140525X0004855X .

Theory, a computational framework that describes how to extract a sensory signal from background noise. Signal Detection Theory effectively describes how the brain overcomes noise in the environment and noise resulting from its own internal processes in order to perceive sensory signals; it has not, however, been able to explain Weber’s Law.11 The psychologist Stephen Link has written extensively about Fechner’s experiments, and created a model explaining Weber’s Law in terms of the accumulation of sensory impulses; more impulses allow the brain to notice bigger stimuli.12 What Link could not explain was how the brain factors out the magnitude of the starting stimulus.13 Stanley Steven’s Power Law fit curves to data points of sensory detection but used averages and could not explain individual data points.14 None of these models managed to account for how the brain distinguishes differences differently depending on the starting magnitude of the stimulus. Meanwhile, in the context of movement education, Dr. Feldenkrais knew that we had to decrease the magnitude of what we were doing in order to allow our nervous systems and brains to notice the difference between various ways of performing a movement.

Prior to the work in Champalimaud, researchers began to fear that mental phenomena could not be described by mathematical equations. They were concerned that there might be too many confounding factors in the functioning of the brain and that willpower, thoughts, and distractions could not be factored out.

Recent research

The research from the Champalimaud Center for the Unknown, led by Jose Pardo-Vasquez, is innovative; it is the first to create an accurate mathematical model of how the brain processes sensory information. As described in their 2019 Nature Neuroscience paper, Pardo-Vasquez and his team studied the ability of rats to notice differences in sound intensity by recording the time it takes for the rats to respond to louder sounds. Noting that Weber’s Law looks at only one aspect of discrimination—its accuracy—they examined the role played by time.

The researchers fitted the animals with mini-headphones, which delivered sound simultaneously to both ears. The sound in one of the two headphones was made to be slightly louder. The researchers recorded how long it took for the rats to turn their heads to the louder sound, and found that the rats’ behavior followed Weber’s Law exactly.

The rats’ ability to tell which sound was louder depended on the ratio between the intensity or loudness of the sounds. The rats were just as capable of telling the difference between two loud sounds and two soft sounds as long as the ratio between the sound intensities was the same. Just as when we are comparing larger weights, the absolute difference between the two sounds had to be greater the louder the sounds. But again, the ratio stayed the same. The louder the sounds, however, the

30 2020–2022

15 Pardo-Vazquez et al., “The mechanistic foundation of Weber’s law,” 1493–1502.

shorter the time needed by the rats to discriminate between the two sounds.

To describe this psychophysical regularity or rule, the researchers defined a new term: the time-intensity equivalence in discrimination (TIED). The TIED describes how reaction times change as a function of the size or magnitude of the initial stimulus. The TIED is smaller with louder sounds.

The team showed that by adding in reaction times, they are able to derive an accurate mathematical model that links the intensity of a pair of sounds and the time it takes to discriminate between them. Weber’s Law only describes the fact that for sound, it is easier to hear the same difference between two soft sounds than between two loud sounds. The new mathematical model confirms this relationship and also predicts reaction times accurately. The relationship between the loudness of the sounds and the time it took the rats to react was found to be incredibly precise. The research team obtained similar results with sound in humans and with the sense of smell in rats, suggesting their model may be applicable for all senses across species.

Surprisingly, although it has long been recognized that reaction time is a key diagnostic in sensory discrimination (e.g. recall how fast it takes you to hit the brake when you see a squirrel dart into the road), few studies previously explored the effects of reaction time on Weber’s Law. As stated above, most models of Weber’s Law have been cast within Signal Detection Theory, which seeks to determine how the brain picks out one sound or sensation in relation to other less important sensations, and do not address reaction times.15

When sensory receptors are stimulated, they relay how great the stimulus is by increasing the firing rate of the neurons. By studying how the time it takes to react to differences in sound intensity changes when the sounds are softer or louder, the Lisbon research group hopes to eventually explain how stimulus intensity is encoded in the activity of sensory neurons. All senses studied so far display the same relationship. To mathematically describe Weber’s Law, researchers also had to contend with the fact that nearly all sensory judgments can be changed by the context in which a stimulus is perceived. The beauty of the time-intensity equivalence is that it is not affected by other sensory input other than what is being studied in each trial. Despite distractions, the reaction times to softer or louder sounds remained the same if the ratio between the two sounds was above the threshold of noticeable differences.

16 Armin Iraji et al., “The spatial chronnectome reveals a dynamic interplay between functional segregation and integration,” Human Brain Mapping 40, no. 10 (July 2019): 3058–60, https:// onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/ abs/10.1002/hbm.24580

Recent research in brain mapping focuses on flexible brain networks created by the interaction and communication among neurons, known as "functional connectivity." These brain networks shift depending on the cognitive tasks. Rather than discrete areas of the brain being solely responsible for interpreting sensory information, whole networks of neurons may work together to process a sensation and to create a motor response.16 The neurons involved seem to change from moment

31 The Feldenkrais Journal #32 Listening

17 Feldenkrais, “Learning to Learn”.

18 Moshe Feldenkrais, “Image, Movement, and Actor: Restoration of Potentiality interview with Feldenkrais,” Embodied Wisdom: The Collected Papers of Moshe Feldenkrais, ed. Elizabeth Beringer. (Berkeley: Somatic Resources, 2010), 101.

19 Layna Verin, “The Teaching of Moshe Feldenkrais,” accessed November 1, 2022, https://feldenkraisnoho. com/wp-content/ uploads/2012/12/ Feldenkrais.LVarticle.pdf

to moment. Different or larger networks could be activated depending on the intensity of the sensory stimulus. The new mathematical model may help tease out whether brain network activation can explain Weber’s observations that smaller differences are easier to pick up when the starting stimulus is smaller, but can still be distinguished for larger stimuli if there is a large enough difference between the stimuli.

Applications to the Feldenkrais Method® of somatic education

The recent research at the Champalimaud Center for the Unknown is consistent with Dr. Feldenkrais’ insight that moving slowly with minimal effort is necessary to discern subtle differences. The brain can then chose the better way. Just as distinguishing between the intensities of soft sounds takes longer than loud sounds, distinguishing between subtle aspects of physical movement takes time. While we don’t need a lot of muscular effort to achieve proficiency, we do need to sense the differences and explore the options. In "Learning to Learn," Feldenkrais writes, “The lighter the effort we make, the faster is our learning of any skill; and the level of perfection we can attain goes hand in hand with the finesse we obtain. We stop improving when we sense no difference in the effort made or in the movement.” 17 Sensing differences is crucial.

To be able to tell the differences between various stimuli and clarify our movement, we must also reduce the strain we hold in our bodies. While Signal Detection Theory does not fully explain Weber’s Law, it does recognize the significance of the brain's ability to filter out important sensory stimuli from background noise. Dr. Feldenkrais said that “the keenness of our self-realization depends on” our awareness of unnecessary effort, noting that “most people do not realize the amount of useless strain they have in their eyes, mouth, legs, stomachs.” To be able to pick up on subtle differences—those that make the difference— we have to reduce the background straing and constant firing in the brain. When “your brain becomes quiet . . . you see things that you never saw before. The possibility of making new combinations, which were inhibited before, is restored.” 18

Feldenkrais often combined movements in novel ways, which required students to slow down and pay attention before even attempting to engage in the lesson and “mobilize”. “Making you aware of the minute interval between the time your body mobilizes itself for a movement and [the moment] you actually do that movement . . . allows you to exercise that capacity for differentiation and to change.” 19 The research done in Champalimaud, which describes the time it takes

32 2020–2022

to react to differences in sensory inputs, clarifies that sensing slight differences requires more time.

Knowing the mathematics behind Weber’s Law and the time-intensity equivalence in discrimination may not help people move better.

Understanding that our nervous systems can sense differences better when muscular effort is minimal can help students of Feldenkrais® lessons to appreciate the easy movement that improves how they feel and use their bodies. The deeper understanding of why this takes time afforded by the research at Champalimaud is good confirmation.

Feldenkrais lessons often seem to create magical results. Weber’s Law and its refinement provide insight into why.

33 The Feldenkrais Journal #32 Listening

The Advantages and Disadvantages of a Diagnosis: The Case of Yuval

Michal Ritter

Yuval first came to my office with the complaint of lower back pain. The stiffness in his movement was immediately apparent. At 65, Yuval walked without differentiating the main parts of his body; his chest and pelvis moved as more or less one unit. In addition, his knees remained bent as he walked. As we approached one another, I could see that there was no expression in Yuval’s face. His voice was unclear.

These qualities of movement are all typical presentations of Parkinson’s disease.

According to Yuval’s answers in my routine questionnaire, however, he had not received a diagnosis and was not taking any medications at this point. He considered himself to be a “healthy person”.

During our first Functional Integration® (FI®) lesson, Yuval began to feel the ability to move with greater ease and less effort. He became aware of his breathing, accompanied by the movement of his ribs and diaphragm. In feeling the balance between the agonist and antagonist muscles, Yuval was able to distinguish between his chest and his pelvis. This newfound awareness contributed to his uprightness when standing and walking at the end of the lesson. Yuval realized the difference. Rediscovering the ability of his jaw to move readily changed Yuval’s facial expression, and with the hint of a smile he reported that he had almost forgotten of his back pain.

I was thrilled; it was surprising to observe such a change during one lesson. I wondered what role the lack of a diagnosis had played in Yuval’s ability to improve so much so quickly. I was impressed by how receptive Yuval was to the options I put forward during the lesson. He embraced them with great curiosity and optimism. Furthermore, Yuval accepted my suggestion to start a series of Feldenkrais® sessions.

Yuval and I continued to work together for three months, at which

34 2020–2022

point Yuval reported feeling much better. He said that his back pain had disappeared completely and that he enjoyed significant improvement in performing his daily life activities.

Dancing to rhythmical music was a regular part of our lessons. Yuval seemed to enjoy every moment of it, his body responding to the music with a soft, smooth motion. So I suggested he ask his wife to dance with him, but he determinedly refused, claiming that his wife would not be happy to dance with “such a clumsy man like me”.

Every so often Yuval would tell me that his wife had various complaints about his appearance and functioning. She was not happy with the way he moved, saying he walked with a bent back and did not move his hands while walking. She said that his facial expressions were different from what they used to be. She urged him to see a neurologist in order to understand what had caused these changes.

I wondered whether Yuval’s wife had already assumed a diagnosis. Fearing what the future could bring, she may not have been able to recognize the progress that Yuval was making through our FI lessons. Later on, Yuval told me that indeed, she had guessed the diagnosis a while before.

Yuval finally gave in to his wife’s urging and visited a neurologist. The title that doomed his fate came as a surprise to him. Just as he was experiencing easy and free movement, feeling more secure, and enjoying his ability to dance, Yuval received the bitter diagnosis: You have Parkinson’s disease.

I was also surprised when I saw Yuval at our next lesson, shortly after he had been diagnosed. Yuval walked in stiffly, his knees bent, which reminded me of our first encounter. I didn’t understand what had happened. When he sat down to take off his shoes, his right hand began to shake vigorously—a symptom that hardly manifested before—and it took him a long time to carry out the task. Then, without looking at me directly, in a hoarse voice, his face frozen, Yuval said: “I have Parkinson’s. Now I understand why my wife was complaining all the time.” “And what about the tremendous progress you have experienced during the past months?” I asked. “I don’t remember that I made any progress. With a sickness like this we just deteriorate,” Yuval answered sadly.

I asked him to lie on the FI table and placed a flat round air cushion behind his chest. I gave him an FI lesson in which every movement came to pass freely through his chest, aided by the air cushion under his ribs. The movement was transmitted readily throughout his body and his breathing pattern changed to include the full expansion of his entire rib cage.

At the end of the lesson, when Yuval stood up and began to walk, however, he resumed the truncated gate he had displayed at the beginning of the lesson. He thanked me and left with a despondent look in his eyes. I feared that the achievement of his journey so far had been lost along with the joy of dancing he had experienced only a few days earlier.

35 The Feldenkrais Journal #32 Listening

What happened? Why had there been such an extreme negative change in Yuval’s condition? The answer struck me . . . but could it really be? Could the simple fact of a diagnosis of Parkinson's disease have such an immediate negative impact?

Considering the case of Yuval, and similar responses following diagnosis and the naming of conditions for other students of mine, I would like to highlight some of the negative aspects of receiving a diagnosis, while also acknowledging important benefits.

A diagnosis is a title, a heading at the top of a list of symptoms that fill certain criteria. Nowadays, at least in the western world, it is common to seek and to provide a diagnosis when someone feels badly or when someone is experiencing anything unfamiliar in their health. But what compels patients and doctors to search so hard for a diagnosis, and what effects can receiving a diagnosis have on our bodies and abilities? As complex symptoms appear, such as pain or physical changes, feelings of worry and helplessness can arise and with them the desire to find an official understanding that encapsulates what’s going on, which we often believe will lead to a solution.

It is important to mention some of the advantages to diagnosis. A diagnosis offers more certainty, even if it is difficult to accept. For the patient, the moment diagnosis is given, a sense of control over their life is often regained. A diagnosis is something tangible that they can point to when others want to know what’s wrong. At times, reaching a diagnosis may allow a physician to provide appropriate care, which they may not have considered or implemented without the diagnosis.

A diagnosis can lead to solutions that fulfill the needs of both patient and doctor, alleviating suffering and illuminating a path forward. When a diagnosis is discovered, there are protocols the doctor can follow and clear instructions for the patient regarding how to deal with the problem. At times, the patient receives a prognosis that fulfills the need to know what to expect in the future.

But the process of naming a condition can, at times, become long and exhausting. The state of suspension itself can produce fears about what might happen in various possible scenarios. Ideas about what lies ahead may cause anxiety, which can, in certain cases, become severe.

If and when a diagnosis is given, patients read about the illness on the internet, where information about further characteristic symptoms appear. Patients may anticipate these symptoms and begin to feel them, in accordance with what is “expected” of people with their diagnosis. Curiosity and possibility may diminish as a result as limitations set in. When diagnosed, patients sometimes lose their sense of self, valuable connections to their self-image, and the internal sense of what is good for them.

36 2020–2022

Diagnosis can be a form of prison, or an illusion. Once a diagnosis has been made, patients often come to rely on the medical treatment offered to them as the only option. They become more distant from their own body and more dependent on external evaluation. This dependency blurs their ability to feel and define what is right for them. Patients often come to expect the treatment to do all the work—that way they can continue to live according to their previous patterns and behaviors. But these patterns may have contributed to the development of their condition, and their continuation may in fact cause more stress and damage.

A diagnosis is made at a point in a person’s life when they are temporarily weak. It can perpetuate this state even when the condition that led to the diagnosis is no longer relevant.

When I was 16 years old, my dance teacher told me, in an explicit manner, in front of my peers, that I would never be able to become a dancer. Taking her word for it, I stopped dancing for many years. Studying the Feldenkrais Method® of somatic education enabled me to place a huge question mark on this estimation. Nowadays, despite having been labeled a non-dancer at a formative time in my self-development, dancing is one of my favorite activities, and many dancers and dance teachers take part in my classes.

At the beginning of a Feldenkrais lesson, we may feel it is difficult to carry out a function; some activities even feel impossible. During the lesson, after some reorganization and new experience, we discover that the activity is possible, and can even be carried out easily and with pleasure. Imagine if we allowed our initial inability to become our definitive "diagnosis"? We would never have tried carrying out actions in new and different ways, and we would be living a life of limitations.

Looking back, most of us can remember a label or diagnosis that has limited our ability to function. Only by becoming aware of their effects can we reverse such limitations and regain control of our lives.

A diagnosis is given by one person, or group of people, to another. To what extent are the people giving the diagnosis aware of all the implications of the diagnosis for the person receiving it? This question is even more significant in the case of mental health practice, where doctors are often tasked with determining to what extent a person should be considered normal.

Without a diagnosis, we are more likely to discover self-treatment and an approach tailored to our specific needs. Instead of dark clouds, symptoms can function as red traffic lights, alerting us to the detrimental effects of certain habitual behaviors. Becoming intimately aware of our particular condition, we can experiment with different paths forward. Of course, there is no rule book saying that a diagnosis should prevent us from doing any of these things.

Alongside the medical practice of diagnosis, where identical labels are often applied uniformly to different people in different life

37 The Feldenkrais Journal #32 Listening