4 minute read

Bogie, Bradley and Busing

The Story of Pinellas County School Integration

A nine-part series exclusive to the Gabber

Advertisement

By James A. Schnur

Part 1: Brief Integration Disintegrates

John Donaldson, an Alabama native, came to the historic Gulfport area in 1868. He worked for a man named Louis Bell and married Anna Germain, a housekeeper for the Bell family. In the 1870s, the Donaldsons acquired a 40-acre tract in the present-day Childs Park area of St. Petersburg. They planted some of the earliest citrus groves in the area near St. Petersburg’s Tangerine Avenue, today called 18th Avenue South.

As they harvested crops, the Donaldsons saw more free-roaming cattle than people on the open range between their property and Lake Maggiore. They started a family. Their children played with other youth in a nearby frontier settlement that became Disston City, a predecessor of Gulfport. Historians such as Raymond Arsenault, John Bethell, Walter Fuller and Karl Grismer describe how well this family got along with other settlers in the area.

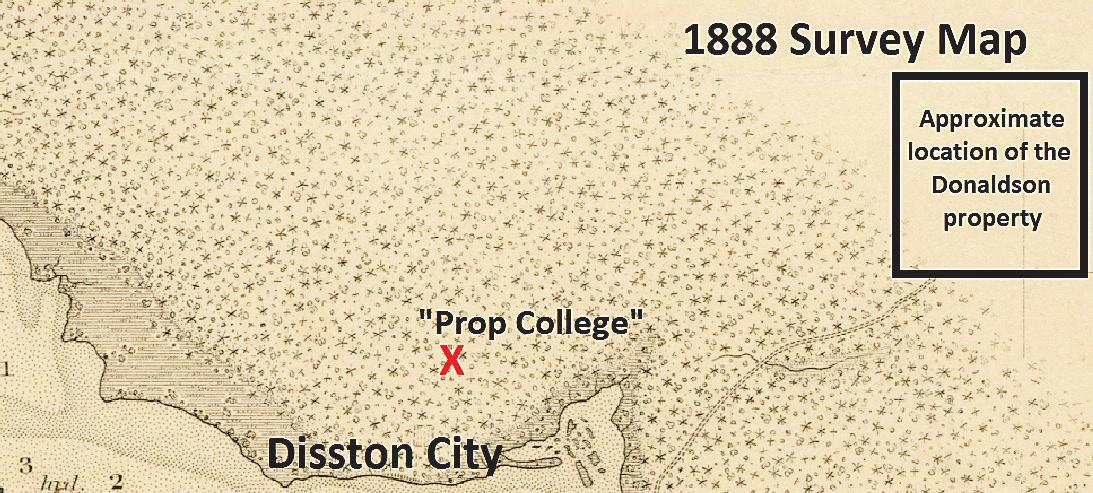

Englishman Arthur Norwood had noticed advertisements in a London paper touting the potential of a new development planned by Hamilton Disston. He came to Florida in the summer of 1886, built a simple school in a heavily wooded area near 49th Street and 26th Avenue South, and began teaching classes that fall. Some of the Donaldson children attended this school.

Davis Elementary School

Students called the one-room board-and-batten structure “Prop College” for the pine logs that propped up the exterior walls. Parents knew this tiny educational outpost as Disston City School, a predecessor to the original Gulfport Elementary (that opened at its present location in 1910.)

The Donaldsons’ experience in the 19th century looked like that of other pioneer families in the area, with one significant difference: Unlike their neighbors, John and Anna Germain Donaldson were Black, and had lived as slaves until the Civil War ended.

The first Black settlers in the St. Petersburg area, their children attended the first integrated school in present-day Pinellas County.

The Duel over Dual Schools

Technically, the Donaldson children who attended Prop College broke the law. Florida’s 1885 constitution included this mandate: “White and colored children shall not be taught in the same school, but impartial provision shall be made for both.”

US GEOLOGICAL SURVEY

The Reconstruction era offered a brief glimmer of hope in the former Confederacy. Agents from the federal Freedmen’s Bureau assisted former slaves who wanted an education who had once faced brutal punishment if they engaged in an act of civil disobedience that threatened the slavocracy: any attempt to gain basic literacy. The state constitution passed in 1868 proclaimed that counties should offer education “without distinction or preference.”

Blacks assumed a handful of leadership roles in Florida during Reconstruction. Jonathan C. Gibbs served four years as Florida’s secretary of state, then became superintendent of public instruction in 1873.

Gibbs died in August 1874. By one account, student enrollment increased by 80% during his brief tenure. Gibbs High School, opened in 1927, bears his name.

Three years after Gibbs died, so did any hope for educational equality in the immediate future. A contested presidential election in November 1876 raised claims of stolen votes. Uncertain tallies in Florida played a central role in a gridlocked electoral college. A February 1877 agreement between northern Republicans who had once pushed for Reconstruction and southern Democrats who had once seceded from the Union finally decided the election’s outcome.

That Compromise of 1877 ended Reconstruction. Southern Democrats once again reasserted “home rule.” White supremacy was reaffirmed in Dixie. Republicans maintained control of the White House. The efforts of the Freedmen’s Bureau ended and new Jim Crow measures disenfranchised Blacks.

Black workers performed much of the labor to build the Orange Belt Railway that put St. Petersburg on the map in 1888. Some of these workers settled in Methodist Town, as well as the Gas Plant district where Tropicana Field and its eastern parking lots sit today. Their drudgery laid the foundation for the Sunshine City, but their children could not attend classes in Disston City.

Plessy v. Ferguson, an 1896 U.S. Supreme Court decision, codified “separate but equal” facilities. That same year, William N. Sheats – the superintendent of public instruction who held the same office Gibbs once occupied – issued a report to the legislature. In this document, he proclaimed that “the Christian people of this State are conscientious and sincere in their belief that the races ought not to be educated together.”

When Pinellas gained independence from Hillsborough in 1912, the new county inherited 22 schools, all of them segregated. Four of these small facilities served Blacks, one each in Clearwater, Dunedin, St. Petersburg and Tarpon Springs. The St. Petersburg school that opened in 1893 later transitioned into Davis Academy, a two-story structure built at the intersection of 10th Avenue South and Third Street in 1914.

Dixie M. Hollins became the county’s first school superintendent in 1912. During his eight-year tenure, schools went from having buckets and wells to drinking fountains and indoor plumbing.

Next week, we learn how a young educator named Dixie encountered an older idea of Dixie that rose again in the twentieth century.

James A. Schnur graduated from Boca Ciega High as a member of the inaugural class that experienced Pinellas school desegregation from first through twelfth grades. To comply with court-ordered busing, he rode the bus for four of those years. He’s written five books about Pinellas communities and has also lectured and published about Florida and Florida education history.