7 minute read

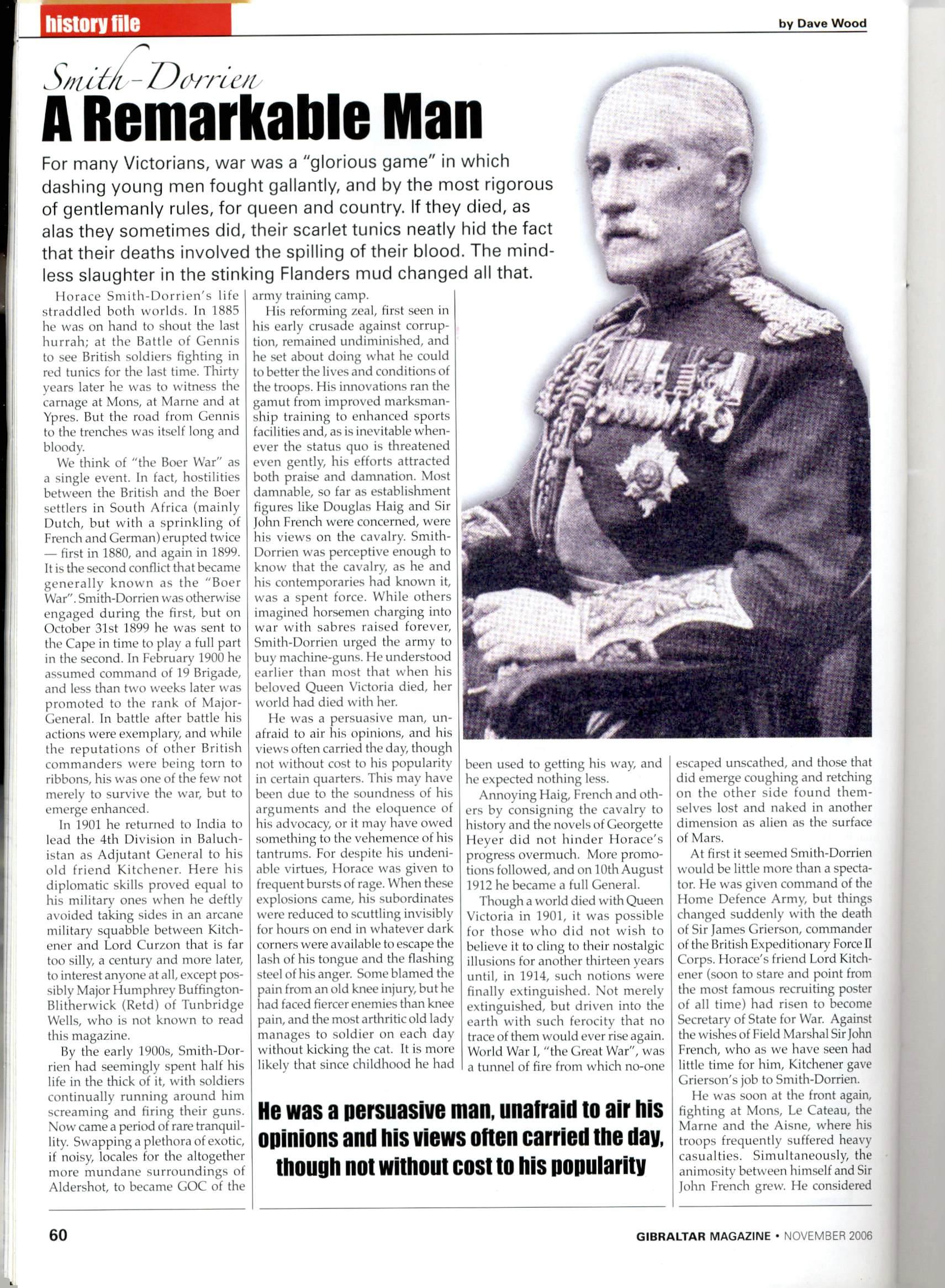

Smit/i -D(HTiaI A Remarkable Man

For many Victorians, war was a "glorious game" in which dashing young men fought gallantly, and by the most rigorous of gentlemanly rules,for queen and country. If they died, as alas they sometimes did, their scarlet tunics neatly hid the fact that their deaths involved the spilling of their blood. The mind less slaughter in the stinking Flanders mud changed all that.

Horace Smith-Dorrien's life army training camp, straddled both worlds. In 1885 His reforming zeal, first seen in he was on hand to shout the last his early crusade against corrupremained undiminished, and hurrah; at the Battle of Gennis tion, to see British soldiers fighting in red tunics for the last time. Thirty years later he was to witness the carnage at Mons, at Marne and at Ypres. But the road from Gennis to the trenches was itself long and bloody.

We think of "the Boer War" as a single event. In fact, hostilities between the British and the Boer settlers in South Africa {mainly Dutch, but with a sprinkling of French and German)erupted twice — first in 1880, and again in 1899. It is the second conflict that became generally known as the "Boer War".Smith-Dorrien was otherwise engaged during the first, but on October 31st 1899 he was sent to the Cape in time to play a full part in the second. In February 1900 he assumed command of 19 Brigade, and less than two weeks later was promoted to the rank of MajorGeneral. In battle after battle his actions were exemplary, and while the reputations of other British commanders were being torn to ribbons, his was one of the few not merely to survive the war, but to emerge enhanced.

In 1901 he returned to India to lead the 4th Division in Baluch istan as Adjutant General to his old friend Kitchener. Here his diplomatic skills proved equal to his military ones when he deftly avoided taking sides in an arcane military squabble between Kitch ener and Lord Curzon that is far too silly, a century and more later, to interest anyone at all,except pos sibly Major Humphrey BuffingtonBlitherwick (Retd) of Tunbridge Wells, who is not known to read this magazine.

By the early 1900s, Smith-Dorrien had seemingly spent half his life in the thick of it, with soldiers continually running around him screaming and firing their guns. Now came a period of rare tranquil lity. Swapping a plethora of exotic, if noisy, locales for the altogether more mundane surroundings of Aldershot, to became GCXI of the he set about doing what he could to better the lives and conditions of the troops. His innovations ran the gamut from improved marksman ship training to enhanced sports facilities and,as is inevitable when ever the status quo is threatened even gently, his efforts attracted both praise and damnation. Most damnable, so far as establishment figures like Douglas Haig and Sir John French were concerned, were his views on the cavalry. SmithDorrien was perceptive enough to know that the cavalry, as he and his contemporaries had known it, was a spent force. While others imagined horsemen charging into war with sabres raised forever, Smith-Dorrien urged the army to buy machine-guns. He understood earlier than most that when his beloved Queen Victoria died, her world had died with her.

He was a persuasive man, un afraid to air his opinions, and his views often carried the day,though not without cost to his popularity in certain quarters. This may have been due to the soundness of his arguments and the eloquence of his advocacy, or it may have owed something to the vehemence of his tantrums. For despite his undeni able virtues, Horace was given to frequent bursts of rage. When these explosions came, his subordinates were reduced to scuttling invisibly for hours on end in whatever dark corners were available to escape the lash of his tongue and the flashing steel of his anger. Some blamed the pain from an old knee injury,but he had faced fiercer enemies than knee pain,and the most arthritic old lady manages to soldier on each day without kicking the cat. It is more likelv that since childhood he had been used to getting his way, and he expected nothing less.

Annoying Haig, French and oth ers by consigning the cavalry to history and the novels of Georgette Heyer did not hinder Horace's progress overmuch. More promo tions followed,and on 10th August 1912 he became a full General.

Though a world died with Queen Victoria in 1901, it was possible for those who did not wish to believe it to cling to their nostalgic illusions for another thirteen years until, in 1914, such notions were finally extinguished. Not merely extinguished, but driven into the earth with such ferocity that no trace of them would ever rise again. World War 1,"the Great War", was 1 a tunnel of fire from which no-one e.scaped unscathed, and those that did emerge coughing and retching on the other side found them selves lost and naked in another dimension as alien as the surface of Mars.

At first it seemed Smith-Dorrien would be little more than a specta tor. He was given command of the Home Defence Army, but things changed suddenly with the death of Sir James Grierson, commander of the British Expeditionary Force II Corps. Horace's friend Lord Kitch ener (soon to stare and point from the most famous recruiting poster of all lime) had risen to become Secretary of State for War. Against the wishes of Field Marshal Sir John French, who as we have seen had little time for him. Kitchener gave Grierson's job to Smith-Dorrien.

He was soon at the front again, fighting at Mons, Le Cateau, the Marne and the Aisne, where his troops frequently suffered heavy casualties. Simultaneously, the animosity between himself and Sir John French grew. He considered

French arrogant and stupid(a view which Haig came to share), but French was his superior, and had the upper hand.

Things came to a head with the second Battle of Ypresin May 1915. French gave orders that Smith-Dorrien considered asinine. Heignored them and recommended instead a tactical withdrawal.French sacked him and replaced him with Herbert Plumer, his choice for the job from the start. The unfairness of this can be gauged from the fact thatPlumer immediately made the same rec ommendation, which French now instantly accepted. It was too much for Kitchener. He promptly dismissed French and gave his job to Douglas Haig,

French, as vindictive as he was occasionally stupid, later wrote a book in which he virulently attacked Smith-Dorrien who, as a serving soldier, was unable to reply.

Back in London, Smith-Dorrien kicked his heels until he was asked to go and fight the Germansin Ger man East Africa (now Tanzania, Rwanda and Burundi). But on the way he fell ill with pneumonia and was unable to assume command. His military career effectively over, he returned home in January 1917 and was appointed lieutenant of the Tower of London.

He was 58 years old, and after a lifetime of almost constant combat a lesser man might have hung up his sword and devoted himself to feeding the ravens. But Horace found life dull without a challenge, and in July 1918, he moved on yet again. He became the Governor of Gibraltar.

It would be nice to say that this is where the story really starts, but despite holding office until May 1923, his time on the Rock was relatively uneventful. It might be imagined that a man whose first act on arrival was to close down the brothels would have been deeply unpopular with the troops,but this does not appear to be so. Autocratic he may have been, and his temper showed no sign of mellowing, but he was fair and decent, and the men knew it. And his celebrated impatience with foolish superiors can have done little damage to his reputation in the barracks.

After five quietly distinguished years, Horace left Gibraltar in September 1923, retiring first to Portugal, and later to England. It would have been entirely out of character for this man of action to spend his twilight years growing roses and snoozing behind a wellthumbed copy of The Times,and it should come as no surprise that he filled his hours with more energy than many a man half his age. He and his wife, Olive (they married in 1902) devoted much time to the welfare of Great War veterans,and Horace still found enough to write his memoirs, which were published in 1925. Here he showed himself a greater and far more magnanimous man than his old advocate John French. Given at last the oppor tunity to extract revenge for the insulting inaccuracies in French's book, he did not do so. French was still alive, and he wished to spare his feelings. Indeed, when French died shortly after the publica tion of Smith-Dorrien's memoirs, Horace acted as a pallbearer at his funeral.

A year later he played himself in a film recounting the story of The Battle of Mons.

Horace Smith-Dorrien died in Chippenham, Wiltshire, on Au gust 12th 1930. This man who had survived a lifetime of fighting in conflicts that spanned the world finally met his death not at the hands of a determined enemy, nor as the result of debilitating disease. It took a car crash.

Oh — and that trivia question with which we began? The Ca nadian mountain, the Australian vineyard, the road in Leicester, the avenue in Gibraltar all named in his memory are self-explanatory. But John Betjeman?

In Chapter 3 of his blank-verse autobiography. Summoned By Bells, the poet wrote:

In late September, in the conker time. When Poperinghe and Zillebeke and Mons Boomed with five-nines, large sepia gravures Of French, Smith-Dorrien and Haig were given Gratis with each half-pound of Brooke Bond tea.

When Betjeman's book was published in 1960,Hor ace had been dead for 30 years. The sepia gravures had long since faded,the tea had long been drunk. But his name was still fresh. He would have liked that.