4

Storie S from

Alma

Aman

Angela Hui

Cassius

Catherine Cheyenne

Elena

Estefany

Giulia

Hualing Nieh Engle

Jomar

Luna

Mark

Mia

Michelle Zauner

Min

Mio

Rachel

Rebecca

Simu Liu

Stephanie

Teo

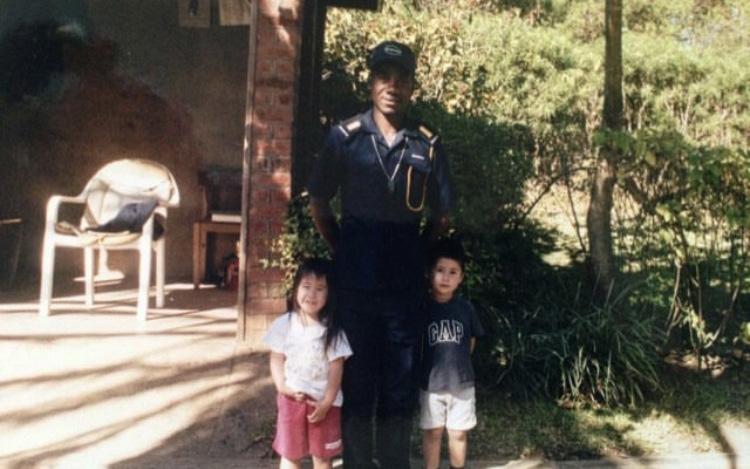

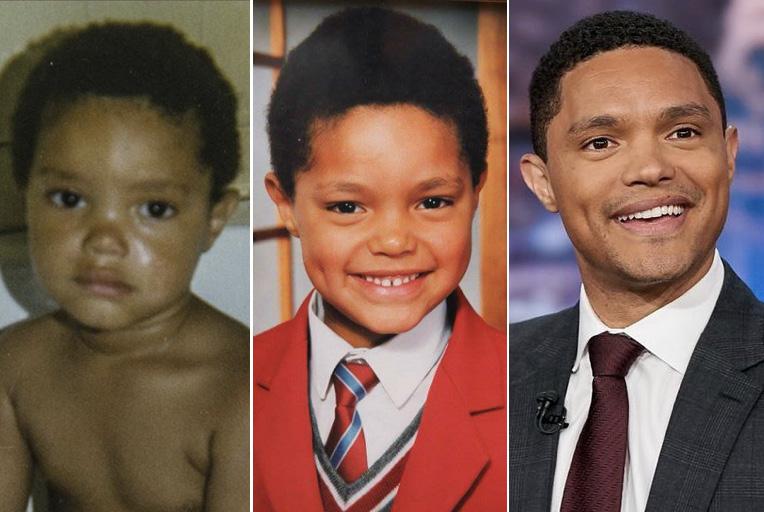

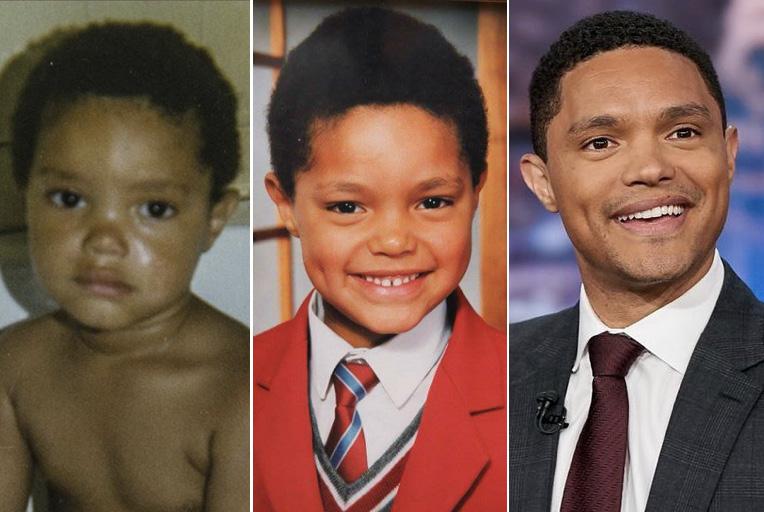

Trevor Noah

Victor

Zaym

Ziyang

t o more people who are battling cultural S tereotype S and S truggling with their own identity

*Ranked in no particular order, based on alphabetical order.

5

Disclaimer:

The content summarised in this project is excerpted from interviews and relevant books for readers. The views expressed solely represent the interviewees’ personal opinions. The public figures summarised from their works only represent my reflections on their statements.

Full names are used for public figures, while interviewees are identified by first name only.

8

This collaborative project comes from 20 in-depth interviews, 5 secondary research, and my own story. Those 26 stories all come from mixed-race and third-culture individuals.

The primary research includes people born between 1983-2005, spanning different generations who offer perspectives on cultural identity and heritage.

The First-person narrative describes the primary research participants while the third-person narrative depicts the public figures. All stories are individually summarised from interviews and literary works.

Many individuals embody both roles, so I did not categorise participants into distinct groups. This mirrors our shared feeling of disliking rigid labels, preferring a fluid sense of self. Thus, I organised alphabetically by first name to share our stories.

These 26 people’s narratives show 98 years changing within 25,000 words.

Our stories explore complexities of cultural identity – how our sense of self relates to diverse cultural influences growing up. We discuss feeling in-between, adapting to new environments yet maintaining ties to our roots. Diverse upbringings foster varied resilience alongside different internal conflicts.

Over time, many forge their own identity outside stereotypical labels. Identity transcends simplistic categorisation, often self-defined through an evolving process, gradually shaping one’s sense of self and place in the world. By sharing our stories, we illuminate the complex factors shaping who we are and where we come from.

I hope this project offers perspective to those navigating their identity while providing insights to open-minded readers without similar experiences.

I hope these 26 stories build a bridge between different kinds of people in the world - reminding us we are all different individuals, no different originally, simply human.

9

I am Portuguese Croatian - my dad is Jewish Portuguese and my mum is Croatian. I was born in Canada but never lived there, as my parents worked for the United Nations, so we moved between Lebanon, North Korea, Italy and Jamaica while growing up.

Moving so much, I felt I was leaving behind the familiar and starting over constantly.

But as a child, I didn’t appreciate that these experiences were nurturing useful skills. I didn’t realise they were shaping me into an innovative, emotionally intelligent thinker able to adapt to fast-paced environments.

My teachers even suggested learning disability checks because my multilayered thinking was deeper than peers’ and I saw things from different angles. This made it hard to communicate in ways others expected. They said I needed to improve my communication.

When writing early on, I would approach assignments uniquely, unlike English speakers raised in Canada or America. Learning five languages, I thought in multiple tongues simultaneously. It was difficult to differentiate between them in writing at that young age. Although this wasn’t an issue when speaking, writing involved consciously deciding which language to convey my thoughts in - a complexity others struggled to grasp.

Even now in undergraduate studies, these challenges remain to some extent. It is both a skill and fear. To ensure understanding, I will carefully think about who I’m speaking with and how we communicate.

I translate my thoughts into terms they will comprehend best. This is a technique honed through my upbringing.

The language skills act like a claim to belonging - if you can speak people’s tongue, you’re accepted on a deeper level than passport grants you.

Although never lived in Portugal or Croatia, my parents had this agreement that my mom would speak to me in

English and my dad would speak to me in Portuguese. But my dad was in a different duty station majority of the time.

If now they sent me to Portugal to take part in family events, I will not be accepted as the rest of the family is, because we couldn’t speak the same language, I couldn’t make the joke with them, and I don’t have the same nostalgia of a country that they do and living there every single day. Only knowing English and languages from school.

Now losing my Arabic being away from Lebanon, I’ve lost that connection too - now just nostalgia for a past home. I know that when I go there, I will be treated as a foreigner and I’ll feel like a foreigner and I won’t feel like I did when I was a kid.

“ i ’ve al S o come to embrace that i ’ll never have the S ame patriotic feeling S for a country that other S do. i don’t have a deeprooted place that i ’m from, S o i could never fight S omeone in S ulting “my country.” i don’t have that inten Se loyalty that make S my friend S pa SS ionately S upport their nation’S team in the w orld c up. t hi S u Sed to S adden me becau Se there’S nowhere i truly call home except where i ’m Sleeping at night.

but now i reali Se home i S ju S t a placeholder - i feel comfortable where i make my own Space.”

When asked about my background, I normally say I’m Portuguese Croatian. This conveys my family structure and multiculturalism without explaining everything repeatedly.

But I adapt my response depending on who I’m speaking with, to feel more familiar to them.

With Spanish speakers, I say I’m Portuguese. With Brazilians, also Portuguese. With Americans, Canadian. Here in Tajikistan, I say Croatian given the Slavic, post-Soviet culture.

So it allows that immediate knowledge from the other person to know that we have somewhat of the same social norms in us, so they’re more comfortable and they will expect that.

So I’m more likely to be invited to things and be more faster in a simulation and better welcomed by the people that I’m talking to. Also, I only share my full

12 Alma 18 year S old

“You have to adapt very quickly - learn fast and almost be a chameleon. You must immediately fit into a new culture seamlessly so you don’t stand out and can have a normal social life.

But when I was young and would meet my parents’ friends, I was a very aware child, like many thirdculture kids. I’d be discussing politics and cultural heritage at eight years old, asking why certain issues existed because I’d seen things so differently in other places while growing up.”

experience once the conversation goes deeper because I don’t want other people to think I am narcissistic.

Although people could understand what multicultural is like and in theory, each different multicultural person will have a very different experience of how that’s played out in their life. So that means that although you’re somewhat similar, it’s like you will only ever be in understanding of each other’s loneliness or lack of belonging.

My family’s history shows the struggles of belonging. My grandfather was a chemist, but when immigrating to Canada could only get labour jobs like forklift driving. After years of studying science, it must have been difficult transitioning to that role. My grandmother worked to support them as well, the lack of support for immigrant families pressured them out of their aspirations.

Growing up in Canada, my mother faced prejudice because her classmates’ parents assumed she was Pakistani because her name. At the time, Canada had negative sentiments towards Pakistanis, so she was often excluded.

When she had my brothers, she chose a more English name so they could better assimilate than with foreign names.

And when I was growing up in Jamaica for my high school, when the black lives matter movement started well, I was the racial minority in terms of actuality, immediately being the only European descent person in the room making me a target.

So saying that I was Canadian was more strategic for me because otherwise,

people that already knew that I was Portuguese would like to call me a colonist and all these other things. I use it to avoid conflict as another layer.

I suppose it’s not solely about our heritage, but rather a matter of not feeling like I belong, and this feeling has persisted for several generations.

tho Se that S tay S tagnant are the thing S that make my home, not S o much the country, but then i al S o in coming to term S with how i embrace it, i S then reali S ing that it’S S uch an a SSet enough for me. i can be S o much better with diplomacy and being and hold le SS bia S in my view.

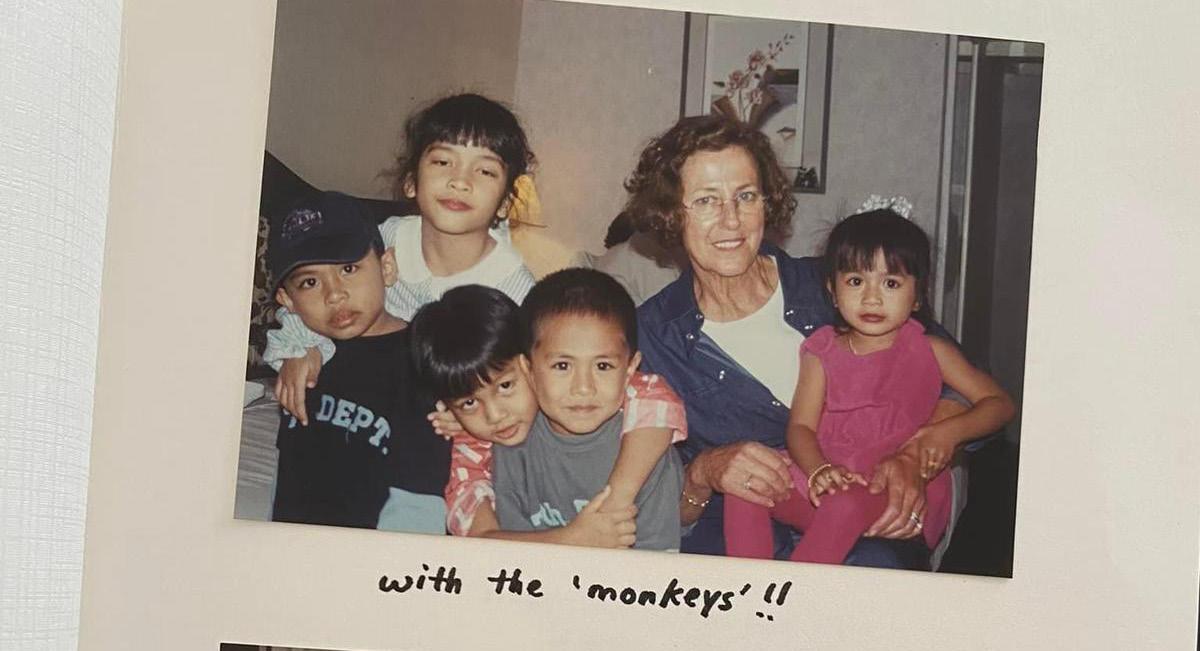

1 Me at age 5 in front of the United Nations headquarters

2 My Baka (grandmother) and Deda (grandfather).

3 My 6th birthday with my family in Tyre.

On the far left is my dad. The far righ you see my mom. Behind me are my 2 borthers and infronto fm be the cake my middle brother had made for me .

4 Me an my parents in london as they drop me off for University (2022).

5 A picture from my persepctive as I paint my part on my highschool graduation mural.

13

5 Me and my mom on the great wall when I was 7, 2012

6 My first flight at 9 months old on my move from Canada to Lebanon, 2004

7 Me and my Baka at our house in Canada, 2005

8 My family and I in the forbidden city in China, 2011

9

10

My oldest brother was at school.

14

My mom and me standing infront of chinese side of the Sino–Korean Friendship Bridge.

5 8 9 10 6 7

Me bowing to a kneeling soldier statue on the great wall of China, 2011

11

12

13

14

15

16

15

My brothers and I posing infront of the Korean Airline plane on our way for a trip on Mnt. Chilbo.

My first climate march at 6 years old in DPRK.

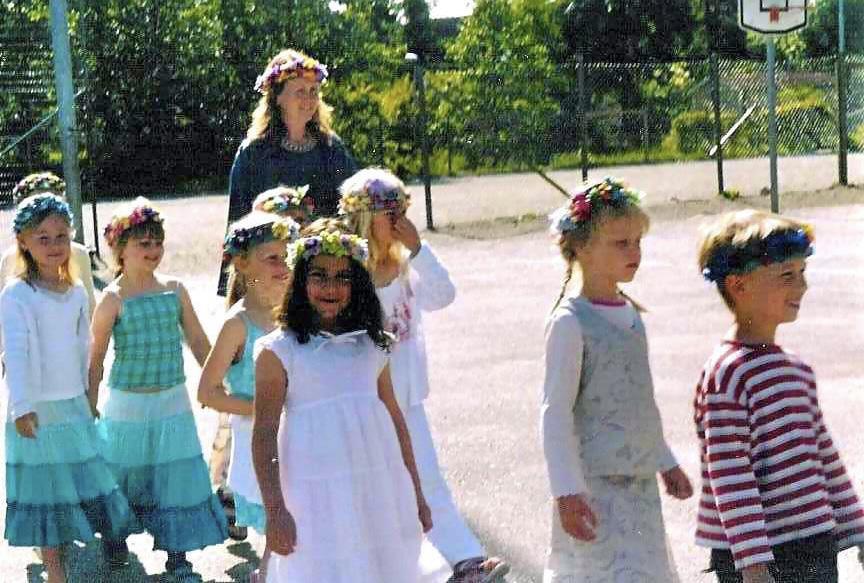

Me in grade 1 doing a school performance with my class in Tyre Lebanon.

When you travel a lot you learn how to get comfortable. This was my make shift bed while we traveled to Croatia to see my relatives.

My grade 5 graduation in Beruit Lebanon.

11 14 15 16 12 13

Me and my grandmother standing infront of our house in Portugal, 2021

33 year S old

“ f rom my childhood onward S , i never felt like i belonged anywhere. t hi S continued into early adulthood, where i tried fitting in with variou S group S - people of different culture S , religion S , etc. i con S tantly S truggled to find where i belonged.”

my diverse roots. Now, because of my upbringing, I feel at ease without a defined cultural label. I can relate to anyone. Whereas before I desperately sought belonging, I’m now content without a specific identity. I can openly accept people of all backgrounds without stereotypes or racism.

cultures will be destroyed by interacting. As a multicultural person, I could enjoy everything, which benefits me as a human.

I’m born to an intercaste couple, My mother is Anglo-Indian, a mix of British and Indian, and was raised Christian. And my dad is a pure Indian Muslim. So they were both of different religions. They was rasied and born in different area in India. India is big country which has more than 200 or 500 different kinds of cultures by different areas, and we have officially 28 languages, although I think there might be around 200 to 300 variations of languages. After having me, we moved to an area with yet another new language and culture. I was raised in this blended environment, influenced by various cultures and faiths.

In this huge multicultural country, you often feel the need to belong to a group identity. I felt left out without that anchor.

As a teen, I saw myself as an outsider while exploring my identity. For example when I identify my religion, like I am a Christian or I am a Muslim, I was trying to fit into both, but both of the groups couldn’t really accept me because I am not hundred percent of Christian or Muslim. When I more tagging myself I felt I am different from my friends or other people, I felt I didn’t belong to them not because other people treated me as an outsider, it was more a self-feeling. I put myself in that role.

Fortunately my parents didn’t restrict my exploration. Their guidance allowed me to learn and understand

“ m y name i S derived from a rabic. a man mean S “peace” in a rabic. i t al S o ha S different meaning S in h indi, meaning “love.” So the root S of my fir S t name e SSentially S ignify “peace and love” between the different language meaning S.”

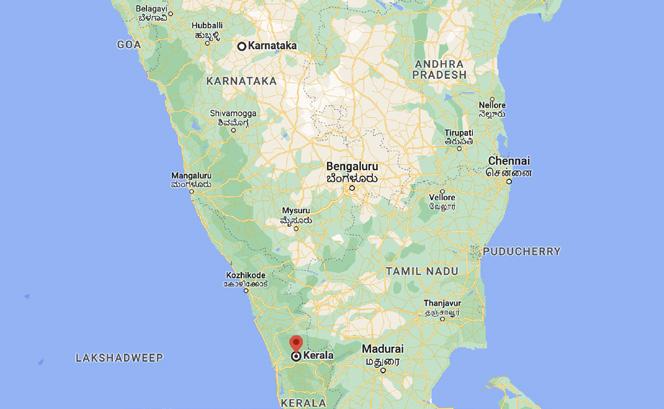

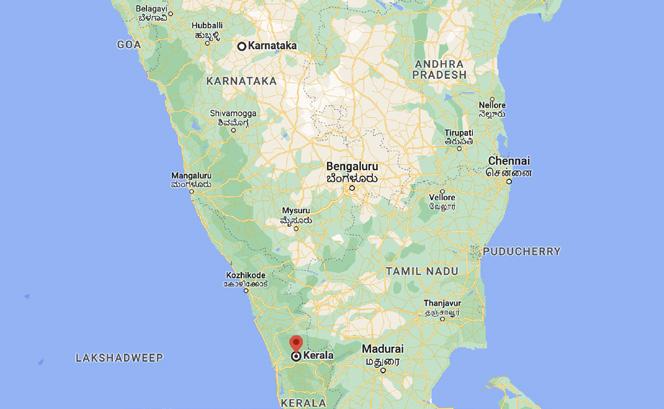

My parents were originally from another part called Kerala and but I grew up I was born and bought up in a place called Karnataka - like mini countries with distinct heritages and languages within southern India. Exposure to different people and media allowed me to pick up various languages as a child.

I currently speak five languages, four of which are Indian. Using local languages makes it easier to communicate with people and understand the culture built on that language and food. Conversations about Indian cuisine spark some people’s interest in trying it, leading to broader talks about culture. I hope to someday showcase the differences between southern and northern Indian food since most Indian restaurants in the U.K. feature northern dishes. Introducing more regional variety could give people a fuller experience of India’s diversity.

But to be honest, people seem less open to cultural mingling than in my childhood. Nowadays people appear more concerned about preserving identity. As a child, I felt people happily interacted across cultures. A gift of my upbringing was experiencing it all through my parents’ open-mindedness. We shouldn’t fear change or worry that

“ y ou don’t need to focu S on having your own cultural identity. t he mo S t important thing i S being a good per S on and treating other S well, regardle SS of culture. at the end of the day, you’re a human being and S o i S the other per S on.

t hat’S how you Should treat everybody, no matter what. f or that, you need to work on your Self and eliminate prejudice S rooted in culture.

t he i SS ue i S mo S t culture S define an “enemy” culture a S their oppo S ite. w hen you align with one culture, it automatically make S the other into opponent S or enemie S. t hi S happen S in i ndia - you’re born into one group, and ju S t becau Se of that, the other group become S your enemy. i t doe S n’t make Sen Se to me.”

16

Aman

1 My family and I dressed in our traditional attire for the Onam festival.

1 2

2 The map of Southern India. (©Google Map)

Angela Hui

*The content in this article is summarised and excerpted from interviews and relevant books and presented for the readers. The views expressed in the text solely represent the personal opinions of the interviewees. *文中內容是作者經採訪和相關書籍摘錄,以饗讀者。 以下內容僅代表受訪者的個人觀點。

“Many immigrant communities are reluctant to report any crime. Always better to take it upon ourselves to resolve whatever the issue is, because the police never believe us and we don’t want to kick up a fuss or rely on others. We’re taught not to speak out, not to rock the boat, keep our heads down and to fit in for fear of attracting unwanted attention on ourselves and our family. For my parents, silence is a form of protection, and dealing with matters on our own means safety. The see the mistreatment as the price of doing business and just another obstacle they have to overcome.”

Angela is the child of first-generation immigrant parents, existing in an in-between space: the inherent crisis of being not Chinese enough or British enough. She grew up at a Chinese takeaway called Lucky Star in Beddau, a village in South Wales valley. From childhood to early adulthood, this restaurant was the centre of their universe, business and personal overlappingit was both the takeaway and her home. Business conflicted with family. Homework was squeezed between precious customer serving time, and she and her two brothers were not spared from chipping in to help with chores, answering phones, taking orders, packing boxes. Growing up a minority in Wales meant being an anomaly in Hong Kong too, meaning she didn’t fit in anywhere fully. She found it difficult to connect to her culture because in Beddau, there were not many faces like hers. She was often told to “go back to your own country” or kids would mock her saying “your parents use dog meat in their special fried rice” and pulled their eyes slanted. Yet whenever she went back to Hong Kong, may have looked like everyone else on the outside but stood out starkly. She called herself a banana - derogatory for looking yellow on the outside but white inside.

“ w hile tradition retain S it S iron grip over e a S t aS ian familie S , like mine, family dynamic S are no longer a S black and white in the face of modernity. f or year S i have been on a treadmill of validation and vanity, trying to pick and choo Se which lane Serve S me be S t. aS i Slow down, ba Sking in thi S moment, everything Seem S to click into place. w hy pick, why not both?”

From the way she spoke, dressed and carried herself, Hong Kongers could spot from a mile off that she wasn’t one of them. Her parents had immigrated to the UK from Hong Kong in the 80s to start a family and seek better quality of life. With little education, their only options were low-skilled physical labour like cleaning or running corner shops, fish and chip shops, takeaways and restaurants. Many immigrants of the time worked hard, sacrificing their own livelihoods to give their kids the best possible life, sparing the next generation their hardships. Her parents also do not have enough English skills, and she and her two brothers often had to act as their translators. She also couldn’t understand entirely Cantonese, undoubtedly presenting some identity comprehension obstacles. She wrote a memoir during the pandemic when hate crimes against East and Southeast Asians had risen 179%. “All my life I’ve hated being East Asian, especially a Chinese takeaway kid, but how does a person learn to hate something they were born into?” Hui writes. Her book was named Book of the Week by BBC Radio 4 and Book of the Year by The Guardian.

1 Angela and her book. (©Angela Hui)

2 Angela and her parents outside Lucky Star. (©Angela Hui)

3 Lucky Star Takeaway counter decor. (©Angela Hui)

17

1 2 3

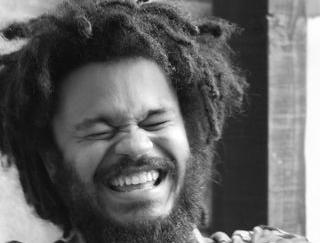

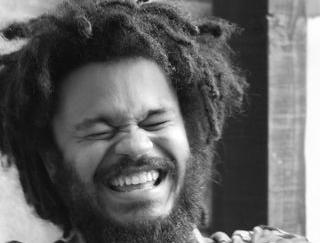

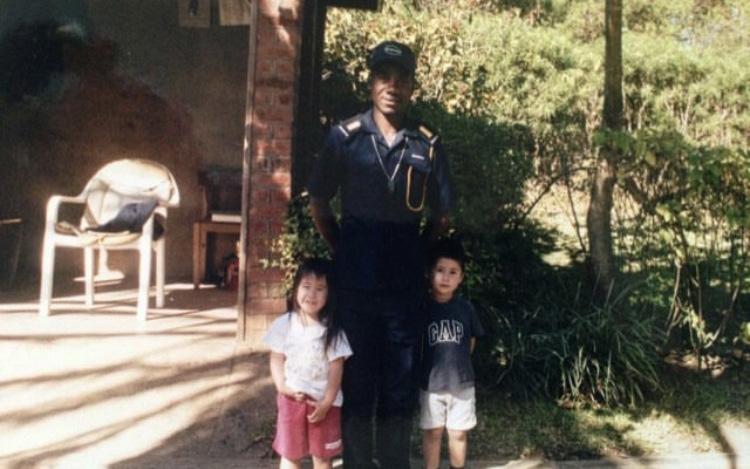

32 year S old

I am racially identified as Black, but have a mixed Caucasian and Jamaican family background. On my mum’s side, her family is from the Forest of Dean just below the Welsh border. My dad’s parents immigrated from Jamaica at some point. I don’t have a strong relationship with my Jamaican family due to my father’s absence and abuse, leading to negative experiences for me. I rarely saw him and cut off contact around age 13, only re-establishing it in my mid-20s, so I had relatively little contact with my Jamaican family while living primarily in white English communities.

I still vividly remember when I was about 7 attending a funeral with my dad. At that age, the unfamiliar Jamaican cultural setting provoked my anxiety, not knowing the expectations and norms. My neurodivergence compounded this. I did one thing violating their basic norms, then my father told others when I still there, “It’s okay, he’s white” as the explanation that I didn’t understand the context, implying I wasn’t one of them. He used “white” to characterize outsiders.

Comparing my childhood to adulthood, people treat me differently, though it’s hard to isolate these changes from moving through different spaces. My self-perception and how others see me have transformed significantly.

In childhood and adolescence, I lacked strong racial/cultural self-consciousness, though in hindsight I can see how they shaped my experiences. Growing up in a predominantly white British community contributed to this lack of awareness. With limited concepts of race themselves, people couldn’t provide a shared perspective on racism.

As we mature, we gain words and concepts to articulate experiences that previously stayed unspoken, potentially significantly impacting our self-understanding. Discussing such experiences is difficult without the language to fully express them. Gaining awareness involves having a community who shares those experiences, whether racial, gendered or otherwise.

Race is a social construct based on how society interprets physical features like skin and hair. Its socio-biopolitical history shapes racial categories in particular ways. As a result, my racialization shifts across contexts, not always aligning with being labelled Black.

You can see in this process with my dad calling me “white” as a child that he was policing the boundaries of who was part of a particular group. But it also showed my genuine unfamiliarity with that cultural context. These categories of white, and black don’t just refer to skin colour but to personality, culture, ethics - many aspects.

There’s a saying in philosophy that “the map is not the territory.” Categories, concepts and taxonomies help us relate to the world in certain ways, like a map simplifying details to aid navigation. But in that abstraction, there are always embedded values, politics, and assumptions - it’s never neutral. It doesn’t perfectly reflect just

I’ve mostly lived in majority white spaces and actually feel more naturally comfortable there. In different spaces, I probably feel similarly to how a white person might - not alienated, but unsure where I stand as people read me very differently. I exist where these categories break down. My experience relates a lot to how queer people describe their identities. So those two different identities’ assumptions also help me a lot to navigate my subjective understanding of this world.

I used to love acting and drama, dreaming of becoming an actor. However, I felt disheartened when I realised that many of the roles I aspired to play were limited to white characters. This socially and historically constructed taxonomy had ingrained itself in my mind, making me feel restricted. Then, I came across the TV show “Luther,” featuring Idris Elba as the lead character. He portrayed a smart London cop, and what struck me was how his blackness didn’t define his role. It resonated with me deeply, as I had always felt disconnected from those actors that focused solely on a character’s blackness, which reminded me of my father’s actions from my past.

At university I was often the only black student around. I’ve been singled out as smart and intelligent, which I dislike - it implies most black people aren’t. As the token smart black person, my intelligence became racialized - the exception to blackness. This contributed to social isolation growing up, leading me to over-identify with academic achievement for self-worth and ego, though it was fragile and stifling. This made me hesitant to explore new things and collaborate with others, hindering my learning process. However,

18 CASSIUS 28 y ear S old

one

reality.

1 1

to

“Sometimes people would say, ‘It’s a real shame you don’t have a connection to your Jamaican heritage’ when I would try and explain the relationship with my father. And I would get quite angry when people dismissed it. I coined this phrase when young - culture comes through the air you breathe, not the blood in your veins.”

Idris Elba in ‘Luther’ Copyright belongs

its production company.

as I’ve grown older, I’ve come to appreciate the beauty of humbly recognizing areas where I lack knowledge and learning from others.

I have a background in cognitive science, informatics, and machine learning. Now I’m more interested in social sciences. I’ve noticed that some of the top figures, like leading AI scholars in my field, are individuals with diverse backgrounds, including those of non-white heritage. This realisation holds great significance for me.

19

“I didn’t fit the stereotype in how I spoke. People would often say, “You’re the poshest black person I know,” because I speak with a middle-class English register. I didn’t see many black Nobel Prize scientists, which meant that racially, there was something in my racial essence that limited my potential for achievement.”

2

“ g rowing up with my n igerian S urname, people a SS umed it wa S my name when i wa S a child, even if they que S tioned it. but a S i got older, people S tarted to a SS ume i mu S t be married to a n igerian man, like the n igerian name belonged to S omeone el Se. i found that more fru S trating. So when i met my hu Sband and had the choice to take hi S briti Sh S urname, i opted for that becau Se it make S life ea S ier, really.”

My grandfather is Nigerian, though it’s a couple of generations back that he moved from Nigeria to the UK. He married my grandmother who was a white British woman, and then my dad married a white British woman too. My grandad was black, African and Nigerian - he was my only grandfather, my only reference point generationally in that sense.

A lot of people were moving to the UK from South Africa at that time, but when my grandad moved here, Nigeria was part of the Commonwealth so he had a British passport. All of my family were born in this country apart from my grandfather. The rest of my family are white British and very focused around Yorkshire, so people don’t assume I’m anything other than white British most of the time.

So generally I’m a person with an invisible dual heritage. But growing up, I had a Nigerian surname which led to a lot of questions, because I think the assumption was always “How does someone who looks like you have a name like that?”

At that time I didn’t get any guidance or support with those situations, but in recent years I can go online and find resources and people sharing their experiences. As a child there definitely wasn’t the sharing, acceptance and platforms to discuss these things that there

are now. I also always like seeing mixed ethnicity families represented in TV and film - it was never shown when I was growing up, so it’s nice now. There are a few actors and people with a similar background, who have a black grandparent, and I quite like reading their interviews to get a sense of how they navigate this.

I watched a film recently with a black or mixed race man reading to his white appearing daughter, which was really nice because it reminded me of myself and my grandad. People would take for granted a grandfather figure as some white man with a big white beard, but my grandad was a black man. Seeing that reflected feels significant to me. It’s definitely a positive thing.

The world tends to be quite a mono-racial place. And if you are mixed race, I think there’s a certain amount you’ve got to accept - that you’re always going to be viewed a bit differently through that monoracial lens. I feel like I’ve spent quite a lot of years battling against that, looking for acceptance and understanding. But actually, even though we probably don’t necessarily want to be educators all the time, we have to be the ones who share our stories and do that education. We can’t wait to be given permission - we’ve got to find and claim our own place.

20

Catherine 1 2

1 My grandma and grandad, 1970s

My mum, from Barnsley with my dad. 1970s

40 year S old

“ t here’S a perception that mixed race ju S t mean S you look like one of your parent S. p eople Seem to think that’S ea S y to under S tand. but that’S not the full picture at all. t here are different culture S worldwide, S o you can’t S ay mixed race look S one particular way. e ven people who did look like my dad - black and white mixed race - have children, and tho Se children may have familie S with people from other ethnicitie S. So you can’t engage with mixed-race identitie S without accepting that we all look different. m aybe that feel S like a new thing in the la S t 20 year S. but obviou Sly, that’S not true nowaday S - all throughout hi S tory, and certainly within the la S t few generation S , it’S been happening. p eople’S thinking need S to catch up to tho Se new generation S.”

I only found out at my grandma’s funeral that she had actually given all her children Nigerian names - so my dad had a Nigerian name and a British name, but he never told me that. My dad was born in 1955. Thinking about how attitudes to black and white couples were even more positive recently, back in 1955 it was really unheard of. I feel my dad was part of one of those new generations having to navigate a mixed race identity without any other role models, research or cultural figures to look to. So I think it was really difficult for him. For those reasons I think he found it hard to connect with his heritage.When I was young, my dad tried using Nigerian food to connect with his roots - we had some African soup once but we thought it tasted so bad we never had it again. But I do feel bad because as a child I don’t appreciate that my dad was making an effort.

Now it’s my turn, I’ve found I’m very curious to learn some Nigerian language and phrases using apps. The technology available now means you can learn about your ancestors’ culture in a way you never could before, which is amazing. It’s nice to be able to say a few words in the language of your ancestors.

I’ve also got two children of my own, and I want to pass on what I can, because they’ll probably have the same identity questions I did, even more so another generation removed.

My kids recently had to research a particular country’s culture for school. They had to look into the food, language and other aspects. Each child had a table, and the whole class would go around to every table as the kids presented on their chosen country.

They could pick any country they wanted. It was really nice because my son picked Nigeria, and I was so proud he felt able to talk about that part of his identity.

I think it’s important schools give children that opportunity without any judgement or questioning why they chose that country. It teaches really valuable skills.

The school does a wonderful job of just learning about different cultures, not labelling or categorising people.

5

3 Me and my dad in our garden in Sheffield maybe 1989?

4 My dad with the next generation, my two sons.

5 My grandmother Kathleen Jessop, from Sheffield for many generations and my dad as a toddler, taken around 1958.

21

3 4

6 My grandfather Warrian Obodo, second from the right with his friends in Sheffield 1950s. They were all enterprising young men starting new lives in the UK from Nigeria and many remained lifelong friends. One became a famous nightclub owner in Sheffield and it’s special to trace my family story along the growth in Black British culture from the 1950s to present day.

7 My grandma and grandad at the pub, 1980s.

8 Me, my dad and my boys in Sheffield, 2017

9 Me and my cousin Simone, 1990s. Her mum is my dad’s youngest sister Margaret who married a man with an Afro-carribean background. They live in Birmingham.

22

6 9 10 7 8

10 My grandparents, 2000s

11 Family gathering. One of my favourite photos, we didn’t all get together very often . This photo has my uncle and my mum in the front. Behind (r-l) is my aunty Maureen, my grandad, my aunty margaret and to the left my uncle ernie who is Maureen’s husband. Ernie has Italian roots, adding another branch of culture to my wider family. I’m guessing around 1980s.

12 Me and my brother with my grandad, 2004

13 My mums family, 1990s. My mum was one of 11 so I have a LOT of cousins! Me and my brother are the only ones with a mixed background and we’ve never felt anything but part of the family. My dad was the first ‘black’ person my grandparents had met, but they were so welcoming. I’ve always felt proud to come from families so accepting of difference.

14 Christmas 1990s. My grandma and grandad in their house, me and my brother really happy with our gifts. We went to their house every boxing day.

15 My husband James, with me and our boys in London. 2022

23

11 12 13 14 15

CHEYENNE

33 year S old

to an S wer “ n ew c aledonia”, and then explain where it wa S and what it wa S.”

But outside the Pacific, when I arrived in Scotland for example, my first answer is generally that I come from very far away. And second that I’m French, from an island off Australia.

“

n ew c aledonia wa S already not that well known, even unknown to the average au S tralian.

i t wa S n’t well known becau Se the fir S t place i moved to when i left n ew c aledonia wa S

au S tralia. w hen i wa S S tudying there , white au S tralian S e Specially didn’t know where n ew c aledonia wa S or what it wa S r ather, people from other place S , like el Sewhere in the pacific, knew where n ew

c aledonia wa S - for example immigrant S in au S tralia and n ew Zealand, or people from f iji and other pacific i Sland S.

but white au S tralian S generally didn’t, unle SS they had been there on a crui Se S topover. f rom the moment i left n ew c aledonia, whenever S omeone a Sked where i wa S from, i ’d have

I’m basically an indigenous person from New Caledonia. So my cultural heritage is very much that part of very native, but also because we’re still very much French and we have administratively we’re still French and our school system is French. We speak French.

That was basically my experience growing up, except when I lived in Vanuatu after finishing my bachelor’s degree. When I lived in Vanuatu, everyone knew what New Caledonia was because before colonisation, New Caledonia and Vanuatu were very linked culturally. So people there knew of those links even though colonisation severed them. When asked where I was from, they would usually first guess Fiji, then ask if I spoke French when I said New Caledonia. Even though we are still very much French there.

So there is a thread in how I answer that question. In the Pacific I would just say I’m from New Caledonia and expand on it being close by or French depending on people’s reactions.

My grandfather on my father’s side is French. So there was already a multicultural divide in my family - half of my family, or two thirds, are native, and the other third is very French. When my grandparents got married in the early 1960s, the priest would only officiate the wedding after 10pm, when everyone had gone home, because he didn’t want to marry a white man and a black woman officially. So growing up with both native cultural background and a lot of French cultural history, as well as the heavy history of colonisation in New Caledonia, brought a lot of challenges in learning to navigate how people related to each other there.

So my mother tongue is actually French now. Oddly, it’s my mother tongue because it’s the one I retained - before starting kindergarten I only spoke my parents’ native languages, but when French was introduced in school I lost most of those and only spoke French. I didn’t start picking up

24

1 3 2 4

my native languages again until middle school. But I have a French accent when I speak.

In New Caledonia we have a very weird mix of underlying heritagewe’ve picked up a lot from French culture, like cuisine and habits. You won’t find a person in New Caledonia without wine and baguettes in their kitchen - those staples brought by the French stayed.

But we’re also influenced by our geographic situation, close to Englishspeaking countries but also Southeast Asia. So staples in most households include wine, bread, rice and noodles. It took me a while when away from home to get used to not having bread or rice at every meal.

We use a lot of things well in our cooking, which comes from the pre-colonisation native culture that we try to keep. It’s not just food but habits and culture too. There are things unique to New Caledonia I can’t find elsewhere that I have to get sent from home, even just snacks, spices and candies that are part of the culture I grew up in.

“ i don’t have any accent when i Speak f rench, becau Se my grandad and mo S t of my dad’S family are teacher S - f rench teacher S So i learned from a very early age to Speak properly, pronounce word S correctly, and u Se proper grammar and Sentence S i had a very nerdy background in that Sen Se. but it al S o meant that for a lot of people, if they hadn’t heard me Speak, even back home, they wouldn’t believe i wa S actually a native. f or example, even S ome of the S ignificant other S of my cou Sin S , if they’d only heard me Speak f rench on the phone to my cou S in and thing S like that. a nd then the fir S t time we met in per S on, they’d immediately S ay:“o h wait, you’re not white!”

New Caledonia (©Google Map)

1 Port Vila - New Year day at the beach because its too hot for anything else.

2 1997 - on my mother’s family’s tribal lands.

3 Maré, New Caledonia.

4 Mom’s grandparents hut on tribal land.

5 Phare Amédé.

6 Noumea - Port Moselle.

7 Something from home ends up on my walls wherever I go.

8 Phare Amede

25

5 6 7 8

10

11

12

26 9 13 10 14 11 12 15

9 Dad’s parent. Grandma was indigenous Kanak and Grandad is full French expat.

Visit of the Cultural Centre Jean Marie Tjibaou - Mom, Cousin, Grandfather and I.

Drinking Kava (traditional drink) with Tongan and Fijian friends (and mom).

Aunt, Mom, colleague and I, drinking Kava - Port Vila, Vanuatu.

13 Family friends excursio with Mom and I.

14 Grandfather planting a tree for his 6rth grandchild.

15 West Papua candidacy to Melanesian Spearhead Group brough to the MSG Secretariat.

I was born in Romania, from Romanian parents, and moved to the UK when I was 22. The way I respond to “Where are you from?” has changed significantly since I first moved here. I used to be quite naive and openly share where I was born - a country that unfortunately doesn’t have a very positive image these days. As I went through university and entered the workplace, I became more aware of how I am perceived.

I felt those around me did not welcome me warmly. They expected, in simple terms, for me to be a “black sheep” who would do something wrong, based on stereotypes about my home country. This is a shame.

So nowadays, how do I answer that question? I went through a phase of avoidance, saying I was born on the continent rather than being straightforward.

But now, as I have gained confidence in my professional status through studying and working hard, I feel I have shown I am not a “bad” person. This gives me the credibility to just state where I am from.

Does my answer change depending on the situation? If I feel I am in a friendly setting, I find it easier to share my origins. In environments where the question seems to come out of nowhere, I still feel guarded and tense, but I do still answer honestly.

When younger and first moving abroad, you’re braver because you don’t know better. The challenge comes when you start perceiving how others interact with you. The “real world” differs greatly from the university bubble and comes with loneliness you don’t anticipate.

As I said, I now feel self-defended in my identity, which is what saddens me most - that people’s first question is often “Where are you from?” rather than something like “What interests you about this sport?” when I try to join a club. I expect interest in me as an individual, not assumptions based on my background.

I went through a time when I retracted, when I avoided interacting when I didn’t want to be in those social circumstances. There used to be a time when I used to joke and say, I bet you someone will ask me what I’m from at this event, nobody is gonna focus on my research or my project or what I did. The first question would be, where are you from? Was all I want to talk about was of the amazing things that I had done. I wanted to share that because I thought that was successful.

These experiences taught me people likely do not have positive expectations of me. But gaining confidence through my professional and personal growth has better equipped me to

tackle the “where are you from” question head-on. I am different and will forever be seen as different - but that is okay.

“i’m actually not S tupid - i ’m quite clever when Speaking another language. but a S you go through life, i only S tudied here in the uk . i f you a Sked me to tran Slate my work or S tudie S into r omanian, my family’S language, i would S truggle. i tend to S witch back to e ngli Sh. So in expre SS ing my Self generally, i ’ve noticed recently that i ’m lo S ing the ability to fully convey what i want in r omanian, S ince i don’t u Se it often - only with my immediate family.”

The way I use the language is still for me, still a tool to come across, a tool to express myself. Whilst with the Romanian language, it’s very different. I am able to use words that maybe are very unique for that space. They cannot be translated or maybe a few words that we use in English, we only translate them in a word in Romanian or there are, as I said, there are some words that actually are so full of meaning and they are only specific for that place. English isn’t my native tongue, so I see it more as a tool to connect, build bridges, and make impressions. When I use this language, my thoughts go quickly and think how am I gonna translate it.

I find it hard to express myself in Romanian because I cannot find the words. I do not remember how to say certain things, because they would not be everyday words, they would be unique words, and I would find it hard to remember how do I say that. And I would stop and I will take a deep breath in, and I will stop and think.

I always when I get stuck like this and I’m not able to say things in Romanian, is more often with my brother who just talk very fast and challenge and we’re debating about something. And I would not be able to keep up and I would stop that would say I am losting some languages now. and he would laugh and he will slow down. But it is definitely I am losing myself. I think that what I’m losing is that part that allows me to say those nice things in another language.

27 ELENA 39 year S old

I don’t want to feel ashamed of where I’m from. I want to believe I actually bring many benefits. Being born in one country yet only living as an adult in another gives great adaptability and resilience - it makes me more flexible and creative individually. I see that in my daily life; I adapt to circumstances quicker because I had to learn how.

Obviously there is nothing to be ashamed of. As you said, people have certain images about countries and individuals, but we aren’t all the same. I may behave like people here, but when I speak with an accent, I’m clearly different and not fully accepted. The same happens when I’m in Romania. So to me, belonging means being accepted. When that acceptance doesn’t come easily, I feel I don’t fully belong anywhere.

I’ve been stuck between these two worlds, like each has half of me and I’m constantly seeking the other half and a space that feels whole. This feeling is like wanting coffee but not knowing where the machine is - it’s just a different setup that I have to relearn.

“ i believe that when looking at out S ider S - people who don’t belong to our village - the fir S t priority Should be en S uring the out S ider you welcome in won’t harm your community. but after that initial caution, you Should welcome them. i n my ca Se, even after many year S of feeling out S ide the village and S till not fully belonging anywhere, i keep waiting and hoping. i may be clo Ser now, peering in the window, but i ’m not yet in S ide.

i ’m in between two village S , continually trying to under S tand my identity and where i belong.”

What hurts is how people perceive me at face value. Like that diamond covered in mud, I know underneath there is the value I want others to see.

The negativity is just surface-level dirt; not everyone or everything represents the bad parts that may have occurred.”

28

“I think deep down it’s like having a diamond ring while doing muddy gardening work - you know its inherent value, despite appearances. That’s how I feel about my cultural background.

It brings so much - poetry, intense emotions typical of Romanians who’ve had to be flexible across empires. It brings drive and commitment, as Romania has persevered through harsh times to improve itself.

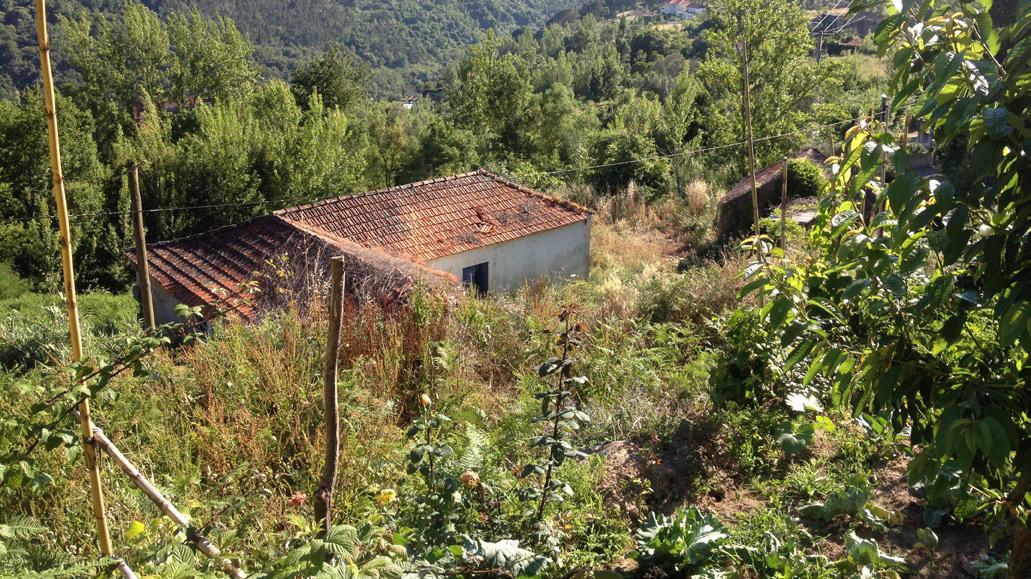

31 year S old

I was born and grew up in Venezuela. My dad moved to the country when he was nineteen, which is quite complicated. I hold a Portuguese passport but would say I’m from Venezuela. I have to explain this over and over, as it easily confuses people. For example, when I told my Scottish boyfriend’s family, they sometimes assumed I was from Brazil or Colombia since I mainly speak Spanish and some Portuguese. People base assumptions about where I’m from on the languages I know.

The time I spent in Venezuela gave me a great sense of humour and open-mindedness. Many multicultural backgrounds mixed there - half Portuguese, half Spanish, half Italian - very common. Venezuelans make jokes but appropriately, so you don’t feel uncomfortable. When I moved to Scotland, I kept this same outlook. I knew my name had alternate spellings and pronunciations here, so at first, I just let people say my name however they wanted. But I changed this after someone made offensive jokes about it. Since then, I ask people to call me Steph instead of Estefany.

Having changed countries several times - from Venezuela to Spain and Portugal, and now Scotland - I feel disconnected from many things, both Venezuelan and Portuguese.

To our Portuguese family, we’re the foreigners, the Venezuelans. I also felt this back when living in Spain with some of my sisters, many things there resonated with me. Now in Scotland with my partner, my heart is here too. I’m a mix of all these places - I don’t need to choose just one. These varied experiences shape who I am today. And because of them, I can speak different

languages and navigate the cultures.

I like exploring fusion projects out of curiosity - like friends mixing flamenco with bossa nova - blending Spanish, Latin, and Brazilian heritage. When I explore these cross-cultural things, I feel supported. This fusion shows in the food our family eats too. I was never a huge fan of typical Venezuelan Christmas dinners - we tend to have more Portuguese-style meals. This just feels normal to mesome dishes take me back to Venezuela, others to Portugal or Spain.

“ i ’m S till figuring out what it mean S to belong. i n general, i think people with mixed background S like me will alway S have a Sen Se of exploring and trying to find where we fit in the world.”

I know how to speak Portuguese but it’s true I procrastinated properly learning and getting deeper into it. I’m not great at writing Portuguese since I never learned grammar - only speaking, listening, and reading it during summer holidays with my Portuguese family.

My dad moved to Venezuela at nineteen and never spoke Portuguese with me. It was easier for him to just speak the language I already knew rather than teach me Portuguese. But once he bought me a record of Portuguese-Canadian artist Nelly Furtado when she was first getting famous. Now I still remember the lyrics to “I’m Like a Bird” - it was interesting to hear some songs in Portuguese.

29

“My background is split between Venezuela, where I was born and raised, and Portugal, where my dad was from. I don’t feel fully connected to some aspects of Venezuelan culture and people, but I also don’t feel connected to the Portuguese side either”

ESTEFANY

1 3 2 4

1 Portuguese family.

2 Portuguese family visiting Venezuela.

3 Parents, sister and cousins.

4 Cousins harvesting in Portugal.

I have so many questions for my late father that I’ll now never get to ask. I want to ask my dad about navigating migration because I feel like I’m reliving his history in Scotland.

My own migration makes me feel closer to him. I think my dad was a brave person. He had to learn how to interact with and get involved in a new community. He came to a new country and learned a new language, even though he was already 19. Those two languages have similarities but it was still very difficult. He never properly learned how to write. I remember having to help my dad write letters to the council because he thinks he will write a mix of Portuguese and Spanish.

I feel he likely had ongoing feelings of missing home, making me wonder if he ever felt out of place like I sometimes do here.

But they taught me important things - to expand my mind. They and those experiences gave me a new life perspective with fewer barriers, and the drive to explore further.

30

7 10 8 9

7 Venezuela y Portugal Flags in Portuguese Community event

8 Portugl 2016.

9 Puerto Cabello - Venezuela3.

10 Grandmother, sister, mom and nephew.

“You should accept and embrace your own culture. But in the end, no matter what others say is important, what truly matters is how you see yourself. Regardless of external validation from others, you need to selfvalidate - accept, embrace, and affirm your own story and identity.”

“ i believe my own cultural identity i S quite unique and cannot be pinned down to ju S t one country.”

“ d epending on which communitie S here and culture S i ’m feeling di S connected from, i will ju S t immer Se my Self in thing S in that language. So going back to like film, mu S ic, film and mu S ic would probably be the main one that i would try to.”

My heritage stems from Italy, Greece, and Syria. I was born in Rome, representing an already mixed-heritage background. During my childhood in Sweden, where I attended a public school for six years, I had the opportunity to immerse myself deeply in a new culture. It was a significant turning point for me. I learned Swedish as my second language and built my first profound cultural connection.

Moving subsequently to Slovenia for four years presented new linguistic and cultural challenges. I vividly remember introducing myself to new classmates and teachers, saying, ‘I’m Giulia, I’m Italian, but I come from Sweden.’ This confused them, as many people assumed that nationality follows a linear path, and they asked me to rephrase it. My limited English proficiency at the time hindered me from fully explaining my complex background.

Returning to Italy after my time in Slovenia, I encountered linguistic challenges within the Italian language. Addressing individuals in higher positions, such as teachers or figures of authority, required altering my narrative structure in a way I wasn’t used to. It was a difficult adjustment, as Italian was primarily spoken at home, and I had limited exposure to the higher grammatical structures. Consequently, I became hesitant to speak extensively in the classroom, fearing that I might mix verb conjugations. I then moved for three years to Greece, where I further explored a culture and language I had only ever spoken at home before.

Choosing Scotland for my undergraduate and postgraduate studies marked a significant chapter in my life.

Over those years, I embraced my mixed heritage and realised I didn’t need to fit into traditional Mediterranean cultures and stereotypes. Instead, I’ve created my unique cultural blend, finding a sense of belonging in the middle ground. I’ve come to understand that many others share this feeling of not fitting into a single culture and have found comfort in their own mixed cultural identities.

My linguistic abilities extend to Italian, Swedish, English, Spanish, French, and Greek. While fluency may vary due to changing environments, this linguistic diversity has profoundly influenced my personality. I’ve become adept at forming new friendships and adapting to new surroundings, but I’ve also faced challenges in maintaining long-term relationships due to limited practice during my youth. As a result, I tend to seek new interactions over prolonged connections. The fast pace of changing environments has also contributed to my more introverted, observant, and shy tendencies.

I consider various mediums, such as dance, music, films, and books, to be powerful tools for deepening my connection to my heritage, I can express my cultural identity and feel a stronger sense of self, especially through dance. Food also plays a significant role in confirming my mixed background. Combining recipes and cooking methods from my diverse heritages and experiences, I create dishes embodying my unique cultural blend. For example, I will use spices from Syria in my Italian dishes. Food is a way to narrate my background.

“ i ’ve learned that my interpretation of my own culture i S what truly matter S i ’ve di S covered that my ver S ion S tand S on it S own and Should not be compared to S omeone el Se’S experience S.’’

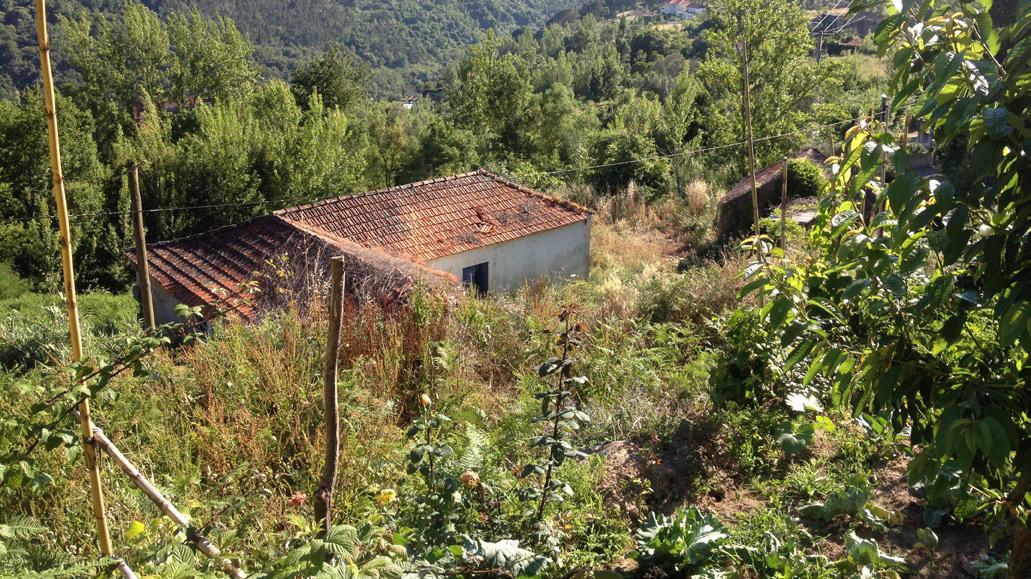

2 In Sweden circa 2001, first time I

3 My first own home in Edinburgh and where my exploration and acceptance of my mixed heritage began, during lockdown, 2020.

4 My first time in the Middle East, I felt very really happy and at home. Circa 2018.

31

GIULIA 1 2 3 4

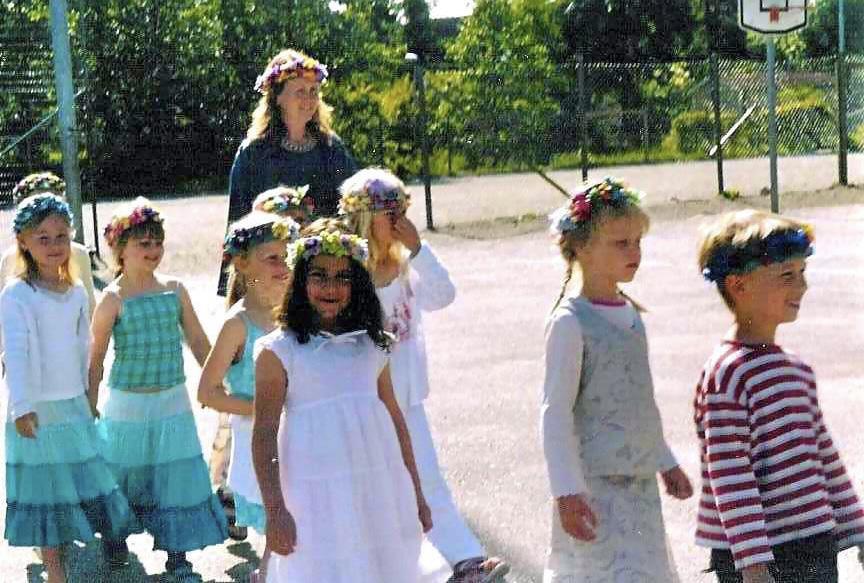

1 Me in Sweden with my classmates during Midsommar, circa, 2003.

explored with playing dress up and theatre play.

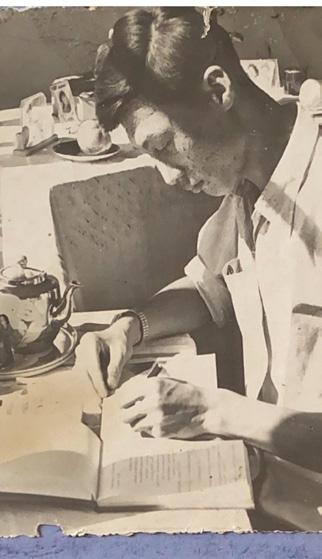

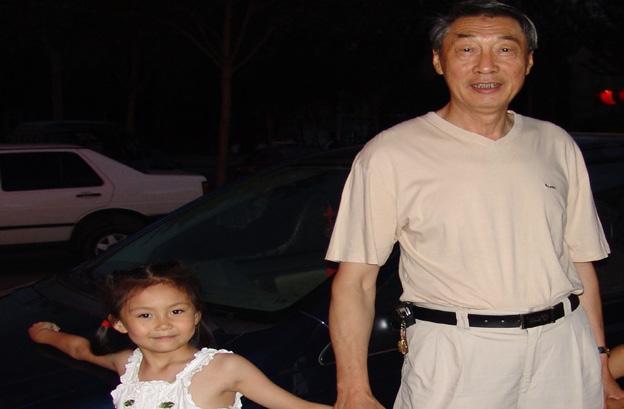

Hualing Nieh Engle 聶華苓 98 year S old

“

i wa S alway S the out S ider. i n taiwan, i wa S conS idered a mainlander. but even among the mainlander S there, i wa S S till an out S ider. i n iowa, i ’m S imply c hine Se. i n a merica overall, i ’m an aS ian a merican. m ainlander, out S ider, outca S t - i ’ve been labeled them all. i even laugh now during conference S becau Se i truly don’t know where i belong anymore.”

From 1925 to 2023, a span of 98 years, the overlapping shadows and complex imagery of this great era, from her homeland in mainland China, to her temporary residence in Taiwan in her youth, and settling in America from middle age until now, Hualing Nieh Engle transcended geographical and cultural boundaries, rose above political and historical divisions, using her consistently delicate and elegant strokes to depict her own winding and moving life, writing down memories of three life stages, three eras and three spaces of activity.

She fled through three generations. Military defeats, civil wars, the War of Resistance against Japan, the Sino-Japanese War, the Chinese Civil War.

As a child, because of her father’s association with the Guangxi warlords, she had to evade assassination by the Chiang Kai-shek forces, hiding in the Japanese concession in Hankou. In 1936, her father was killed by the Red Army while serving as commissioner in Guizhou. In 1937, when the War of Resistance against Japan broke out, she was 14 years old, and became a refugee student. In 1949, at the age of 24, she brought her family from mainland China to Taiwan, immediately participating in the Free China(自由中國)magazine founded by Mr. Lei Zhen(雷震) and Mr. Hu Shi(胡適) . In 1951, her elder brother Hanzhong died in an air force plane crash in Taiwan.

She couldn’t support the left because of what happened to her father, but wasn’t sure about their ideas anyway. At the same time, however, she wasn’t happy with Chiang Kai-shek’s government. She was very alone, neither on the left nor on the right, while it seemed everyone else took a political position. She couldn’t take sides - she was an outsider - so she began writing about the situation of the Chinese at the time. The title of the work was “Metamorphosis” (變形虫) .That was the beginning of her career as a writer.

Gradually, because of Free China magazine’s sharp criticism and incisive rebuttals of Taiwan’s social and political issues, after eleven years, in 1960, it was shut down by the government. Free China was banned, and Hualing Nieh was also put under surveillance by secret police. She lived in fear every day, not knowing which day she would be taken away like them. Lei Zhen was sentenced to 10 years imprisonment with deprivation of political rights for 7 years for “inciting rebellion”; As the only woman in the magazine, Hualing Nieh was not affected for the time being, but lost an important part of her life. At that time, Hualing was in another dark period of her life. The shadow of

*文中內容是作者經採訪和相關書籍摘錄,以饗讀者。

the Free China group had not yet been swept away, and her mother had passed away from cancer. If not for her two lovely daughters, she might have passed away long ago.

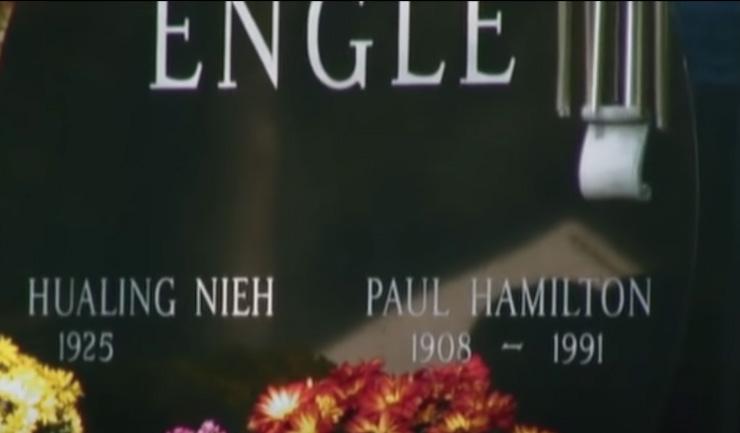

It was at this extremely depressed time that she met the cheerful, humorous American poet Paul Engle. In 1963, Engle came to Asia representing the “Iowa Writers’ Workshop” to recruit writers. At a party, he saw the quietly standing Hualing, the sadness in her eyes deeply attracted him, making him involuntarily want to approach and comfort her. In the autumn of 1964, with friends’ help, Hualing finally came to Iowa, Hualing’s marriage to her ex-husband was already beyond saving. After being separated for 7 years, they finally divorced. Hualing and Engle then embarked on a romance, with a poet’s romance and unique humour, he soothed her heart that had experienced many tribulations over the years. Finally he won her love. Hualing, who had faced adversity for half her life, finally gained a stable, happy home.

They lived in a pink house by the Iowa River, with a willow tree in front. In spring, the willow strands blew in the wind like misty rain, evoking a Jiangnan feel. On the hill behind, there was a hundred-year-old oak tree, thick and sturdy. Engle built a swing on its branches, where Hualing would swing back and forth, as if returned to childhood.

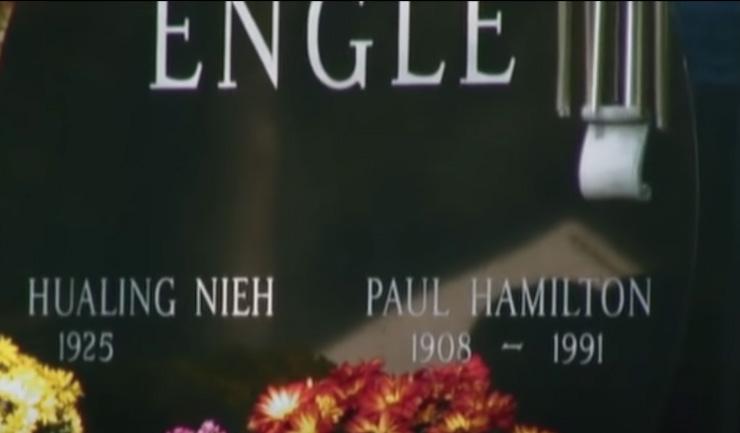

In 1991, when Engle accompanied her to Poland to receive an international cultural contribution award, he suddenly suffered a heart attack and collapsed at Chicago Airport.

Now, she still resides by the Iowa River, writing, writing, writing... What drives her is not success, but the sense of loss experienced time and again in life.

“ i am a tree with root S in mainland c hina, a trunk in taiwan, and leave S flouri Shed in iowa.”

After getting to know writers from many regions and reading their works, she discovered that the fate of the Chinese was also the fate of 20th century humanity. This feeling she gained from exposure to world literature expanded her horizons and influenced her writing.

When she came to Iowa in 1964, she lost touch with her mother tongue. She couldn’t make up her mind which language to write in - Chinese or English? She had already published seven books in Chinese but was also familiar with Western literature. Her novel The Lost Golden Bell,(失落的金鈴子)for instance, was one of the earliest examples of what had come to be called Modernism. She majored in English literature in college, then in Taiwan translated Henry James, Faulkner and other Western writers. After moving to the U.S., she wondered, should she now start writing in English? Or keep going in Chinese? She couldn’t write a word for several years. Then, one day in 1970, she sat down and wrote “Mulberry and Peach”(桑青 與桃紅)in Chinese on checked paper, and suddenly couldn’t stop writing!

32

*The content in this article is summarised and excerpted from interviews and relevant books and presented for the readers. The views expressed in the text solely represent the personal opinions of the interviewees.

以下內容僅代表受訪者的個人觀點。

33 1 6 7 8 9 10 2 3 4 5

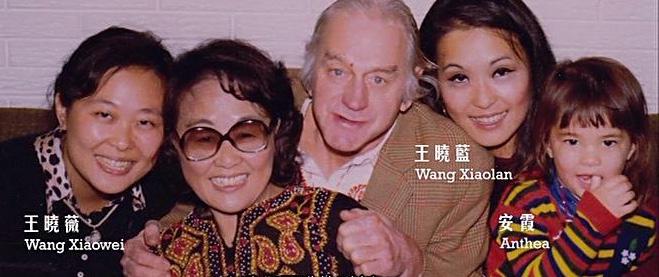

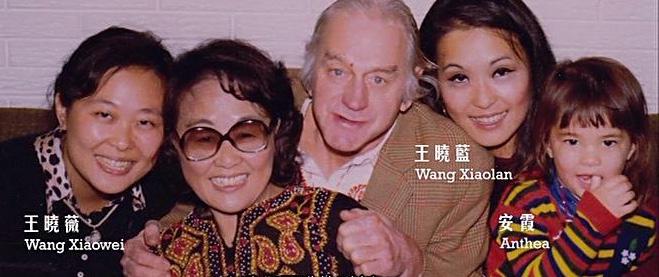

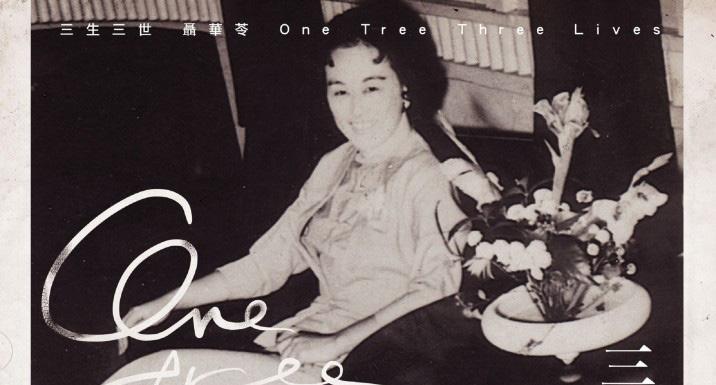

1 Hualing’s family. ©Hualing Nieh Engle

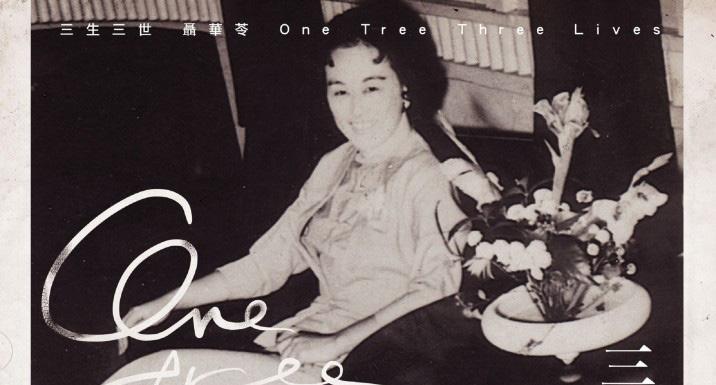

2 The poster of Hualing’s documentary. ©Hualing Nieh Engle

3 The picture of the Free China organizer.©Hualing Nieh Engle

4,5 Hualing and Paul.©Hualing Nieh Engle

6 Hualing, her two daughters, Paul, and their grandchild.©Hualing Nieh Engle 7 Hualing and Paul.©Hualing Nieh Engle

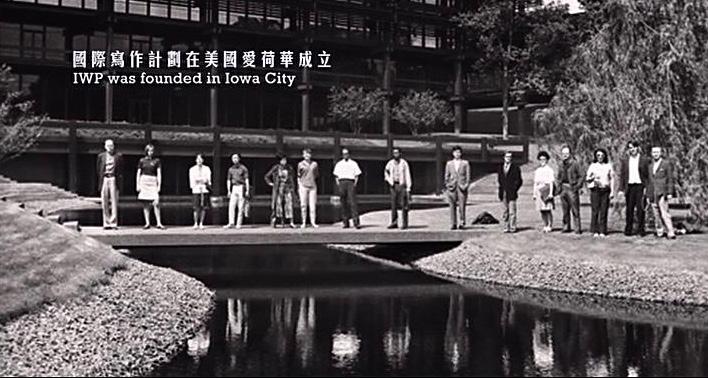

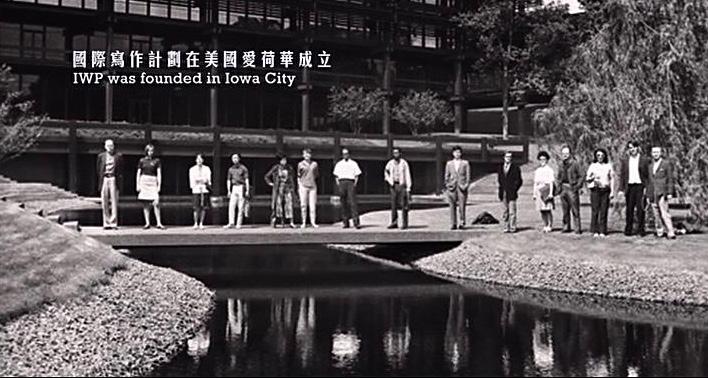

8,9 Iowa Writers’ Workshop picture.©Hualing Nieh Engle

10 Paul’s grave photo. ©Hualing Nieh Engle

Mulberry and Peach was very popular. The book depicts a Chinese woman’s struggles for her life in mainland China, Taiwan and America. It represented a fission of her Chinese and American identities into her writing. The Chinese magazine Asia Weekly named it one of the top 100 Chinese novels of the 20th century. From then on, she kept writing in her mother tongue. She has published 24 books so far. The Chinese experience expressed in another language feels like a skeleton without flesh and blood - like a Chinese person in an American suit. She feels closer to the Chinese writers who write in their native language

In 1966, after obtaining an MFA in fiction from the Writers’ Workshop, she suggested to Engle, now retired from the Workshop, that they start an international writing program specifically for writers worldwide. Their shared vision was to invite published writers from around the world to Iowa City to hone their craft, exchange ideas, and build cross-cultural friendships. With the University of Iowa’s support and private funding, the first group of international writers gathered in Iowa City in 1967 as the pioneering participants of the International Writing Program (IWP).

It was very expensive to bring writers from foreign countries, so they agreed should bring outstanding writers and emerging talent. Each writer was a costly investment. In the first year of the IWP, 1967, they could only afford twelve writers. There was Dai Tian (戴天)from Hong Kong and Ya Xian(瘂 弦) from Taiwan, Ryuichi Tamura (田村隆一)and Tauchi Hatsuyoshi (田内初義)from Japan, Fernando Afable and Wilfrido D. Nolledo from the Philippines. They also had Hans Christoph Buch from Germany, Sankha Gnosh from India, Eugene Nicole from France, Tahereh Saffarzadeh from Iran, Wilton Sankawulo from Liberia, Singaporean writer May Wang, and Daniachew Worku from Ethiopia.

In 1976, 300 writers from around the world nominated Hualing Nieh Engle and Paul Engle for the Nobel Prize for Peace.

*The content in this article is summarised and excerpted from interviews and relevant books and presented for the readers. The views expressed in the text solely represent the personal opinions of the interviewees.

*文中內容是作者經採訪和相關書籍摘錄,以饗讀者。

以上內容僅代表受訪者的個人觀點。

34

“My home in mainland China is gone. My home in Taiwan is no longer there, either. I’ve been here in Iowa for over 40 years. My children grew up here, my grandchildren were born here. I had a full life with Paul Engle. Iowa is my home. We hosted many IWP parties here. My house is too big for me now, but I’m still here. I feel it’s full of my life with Paul. It’s kept me going; I couldn’t live anywhere else. This is my home. I have more memoirs to write.”

“ i can tell when it’S genuine curio S ity and we might have S omething in common. but when there’S a confu Sed face followed by ‘ w here are you from?’, i think ‘ h ere we go again’. i t’S ju S t confu S ing when they’re perplexed and want me to explain everything.”

“ i am trying to See my Self not a S half of anything but a S a full per S on who’S had full life experience S - ju S t a bit more Spread out. i ’m S till working on fully embracing it for my Self and Seeing my Self a S culturally whole, i ju S t draw from more cultural reference S than one. i am making an identity for my Self that feel S like mine.”

“ r ight now i ’m taking a big S tep to explore my own heritage and identity by moving back to i ndia. t hi S i S a deci S ion i ’m making for my Self, not S omething i really want guidance on. i don’t think anyone ha S the right to judge whether it’S good or not. t here’S no one right way to feel about any of thi S.”

My dad is Indian and my mum is English. I moved to the UK when I was about four years old, after living in North India - not a long time, but formative. Nowadays when asked where I’m from, I prefer saying India, though I’ll quickly pass on the question, simply saying I’m half Indian, half British. If people seem surprised I don’t appear fully Indian, so be it.

I know about half the cultural references from the UK and half from India, but never feel fully part of either. It’s harder being a blend of both cultures without knowing many in the same boat.

Having moved around a lot and lived away from home, I lack really strong family ties, though I sometimes visit my Indian relatives. Much heritage hasn’t been passed to me - it’s always been independent learning. I wouldn’t describe my background well. I think it’s something I’m still trying to understand, a lifelong endeavour as a first-generation mixed race person.

I’ve tried engaging with communities of similar experiences - no one else half British-Indian, but all with mixed heritage. We relate discussing cultural navigation. The comfort is that no one asks your family history upon meeting - we all understand. Sharing is welcome but not expected. I know some ask where I’m from out of kindness, so I’ll adapt my answer, like saying I’m Indian but grew up in the UK. It gives them that feeling of connection.

I blend my two cultural sides in different ways. For example, my mum chose my first name to bridge bothit’s traditional in the UK and India. In Hindi it means “moonlight,” while in English it refers to a small, dark-haired boy, which suits me.

Growing up I learned both English and Hindi, though my Hindi has slowly faded over the years. This October I’m doing a Hindi language course in Delhi, as it’s something I’ve always tried picking back up in the UK, but struggle without immersion. I think learning the language will help me connect more to that side of my heritage, overcoming a persistent barrier with my family.

My dad and his family speak a particular dialect, while my siblings mix that with Hindi. So visiting India involves learning multiple languagesnever just one.

Like language, Indian cuisine has vast regional diversity. I enjoy cooking Indian food, though it doesn’t quite match my family’s tastes - I just experiment on my own. I’ll try making dishes like rajma in the UK, and attempt British food like apple crumble in India without an oven.

Growing up around white Brits, connecting to my Indian heritage meant embracing pop culture - musicians, films representing Indian and Pakistani culture. It created a sense of ties when I lacked an actual community.

My Indian and British families don’t interact much - I’m the only link. I don’t share a whole lot with them. I feel Indian in India and British in Britain.

My Indian family may judge me for my whiteness, while my white family judges my Indianness. They don’t appreciate why I’m confused or curious to learn more. I’ve long yearned for information about my life and family history, but it’s not deemed urgent or important to them. Much of my support has come from others in the mixed community, talking about our complicated lives and how we each navigate heritage. I learn so much hearing how others relate to their background.

I used to want to fully fit in, whether in Britain or India. Now I know I’ll always feel somewhat an outsider in both, but I don’t mind. I have lives in each place - friends, work, travel. Sure, some may see me as an outsider, but it doesn’t bother me.

Cultures intertwine with nations and citizenship, which I’m sceptical of. My identity on paper often mismatches how I feel. For me, anywhere could slowly become home through building relationships and belonging.

35 JOMAR 25 year S old

*Jomar is used as a pseudonym for the interviewee.

I feel I’ve become different since first coming to Britain. I think it’s due to cultural reasons, but living here has made me focus more on myself first, compared to when I was in China. Now I’m back in China, though I loved where I studied in the UK at the time, it was truly difficult to stay. These years I live between various cities like Changsha, Beijing and Shanghai, yet don’t feel I belong to any particular place, even country. I only feel I belong to myself. If forced to choose somewhere I feel belong, I’d liken it to a single room rather than a whole house - just having that one satisfying space is enough.

To be honest, I haven’t had time lately to contemplate identityShanghai is so massive and busy that you barely have time to think of others, let alone yourself. I still don’t know if this city is where I’ll settle down long-term. For now, I just try to focus on my own happiness - if I’m content here, I’ll remain. But I sometimes feel alone, like everything is meaningless.

You work 9 am to 9 pm just to pay rent, with no time to reflect on what you like or dislike - just sitting at your desk is enough.

Sometimes I think back to when I was studying in England, especially when I stayed in London. I felt relaxed there because everyone in London seems like an outsider, so I didn’t feel like I stood out. At that time, I always tried to experience new things. When I first arrived, I explored the local area instead of locking myself in my room. I visited different places near my home and used different languages to talk with locals, which could give me a new perspective compared to only learning from YouTube or other social media.

I’ve maintained this adventurous personality even now. Although I’m originally from a northern city in China, I’ve really tried to learn the Shanghai dialect. I feel this language can help me have deeper conversations with Shanghai locals, so I won’t feel excluded. During the long lockdowns, I couldn’t stand being cooped up for days on end. One day I left my room and knocked on my neighbour’s door, even though I had never talked to them before. I just couldn’t lock myself in my room any longer - I needed real human interaction. Luckily, my neighbours

were a very nice middle-aged couple. I went over for tea and opened up about struggling mentally during lockdown. After that conversation, we built a good relationship. So I think if you ever feel uncomfortable and want to find someone to talk to, you could ask for help from near people and also help to search for free mental health counselling services to express what you’re feeling.

Conversations allow the two-way exchange of knowledge and experiences. For example, when I was doing my postgraduate degree, I had discussions with my classmates from other countries and found the different cultural beliefs about where babies come from fascinating. The stories are totally different in Japan, Europe and ChinaJapan has fairytales about babies born in peaches, Europe has stories about babies delivered by birds, and China says they come from apple trees or rubbish bins! It’s really interesting to learn about other cultures. Not only do you gain new knowledge, but you also pass your knowledge to others.

I think that’s the power of sharing perspectives.

36 LUNA 31 year S old

“I cannot feel settled or like I belong anywhere. I’m a homeless who only belongs to myself. “

“I think it would be good for schools to teach respect for other cultures and backgrounds and bravely try new things - that’s quite important. As for me, I don’t personally struggle with this. I consider myself very open to people of all kinds of backgrounds. But if schools could support cultivating this openness and respect, that would be beneficial.”

“ m y grandparent S were all born and rai S ed in taiwan. i ’m 29 now, and when i wa S in nur S ery, my e ngli S h teacher S taught me to S ay i ’m c hine S e. t hat’S why i would S ay i ’m c hine Se. but when i wa S in primary S chool, when i S aid “o h, i ’m c hine Se,” there wa S a girl who turned around and S aid, “ n o, you’re not c hine Se. y ou Shouldn’t S ay you’re c hine Se. y ou’re taiwane S e.” t hat wa S the fir S t time i wa S in thi S weird S ituation of thinking “ w hat’S taiwane Se?” i t wa S S o funny to me. t hi S wa S back around 2000-2001 and i S till remember it clearly - it wa S the fir S t time i ’d heard the phra Se “being taiwane Se.”

If you ask me about the difference between Taiwanese culture and Chinese culture, I can’t really tell - it seems very similar, probably the same. But if you ask about pop culture trends, I don’t know. Culture can be so dynamic with many facets. I remember being invited to a Chinese New Year gathering this year as the only Taiwanese person there.

They were watching the Chinese New Year’s Eve TV show and I didn’t know any of the performers. I know that show is a Chinese tradition, like how Christmas is celebrated here by watching cliche films. But if you ask me to name Chinese singers or artists, I have no idea. Sometimes I can’t understand certain idioms or phrases Chinese people use. The Chinese we speak are a bit different now, also they could figure me out easily by the accent. It was a gathering that I do not very enjoy.

So when asked about my culture, I just say I’m from Taiwan, and the culture is similar to Chinese culture. There is a lot of history behind Taiwanese identity - it’s a very recent, 21st-century development. For me personally, I can say I’m from Taiwan, I’m Taiwanese, but I also celebrate certain Chinese cultural traditions in my own way. But there’s complexity behind what it means to be Taiwanese that is still evolving.

I’ve always doubted what the concept of “being Taiwanese” really means. I don’t know what defines Taiwanese identity, yet also know I’m not Chinese.

If asked about the concrete differences between Taiwanese and Chinese, I couldn’t pinpoint anything specific. Yet I don’t align with those who say if you’re culturally Chinese, you can call yourself Chinese. That broad identification has changed.

30 years ago, Chinese descendants in Singapore and Malaysia also called themselves Chinese. It was about ancestral ties and culture. But I feel that nowadays “Chinese” means specifically supporting China’s nation and systems - a narrower designation that excludes others self-identifying as Chinese.

Before, we could all happily call ourselves Chinese. But now people in Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore, and Malaysia are more reluctant to claim that label. I studied political science, so think a lot about how Taiwanese identity is being actively created by the government to differentiate from China. But I have mixed feelings - this seems more political than cultural to me.

It’s like the atmosphere in the early 2000s polarized people in Taiwan around identity without much healthy debate. You were either on one side or the other. I feel my own position got swept toward one side based on my southern hometown, a stronghold for one party. But is that faction really me?

Went to Taiwan after years away, and I felt like an outsider despite the familiarity. I can’t see myself living there now, though I don’t always love Aberdeen either. I feel more comfortable here - maybe without as many friends, but with a sense of independence. I don’t think I belong firmly anywhere. People should be independent, not claimed by any group or ideology.

Having spent 3 years in the UK, I’m often asked about my background, perhaps because Aberdeen is quite isolated compared to other Scottish cities. Some locals assume I wasn’t born here. A few times, people have randomly shouted Japanese greetings at me on the street, which feels uncomfortable. Assuming someone’s ethnicity based just on appearance doesn’t sit right with me. How you define some one’s race just by their appearance?

This likely also happens because the UK hasn’t had as much Asian immigration as the US - it’s mostly been Indian and Pakistani, not East Asian. When I visit my uncle’s family in California each summer, people don’t ask where I’m from as often. Race is a more sensitive issue there since America is an immigrant society.

I find it fascinating how some old Hong Kong films from the 80s/90s frequently used America to explore Chinese identity struggles, even while HK was under British rule. There seems to be something about the US setting that lends itself to exploring cultural dislocation and self-discovery.

37

Mark 29 year S old

*The content in this article is summarised and excerpted from interviews and presented for the readers. The views expressed in the text solely represent the personal opinions of the interviewees.

*文中內容是作者經採訪摘錄總結,以饗讀者。 以下內容僅代表受訪者的個人觀點。

For example, in the film ‘Comrades: Almost a Love Story’(甜 蜜蜜), which I watched in my early 20s, The main character that Maggie played struggled with her identity. When she meets her boyfriend Leon in Hong Kong, she lies that she was born and raised there because she speaks Cantonese. Leon believes it but still has doubts. Eventually, Maggie admits she’s actually from Guangzhou but has always aspired to be a Hong Kong citizen. I find it so interesting to see her almost trying to fake being from somewhere else. And by the end, she’s moved to America and is happy to get a green card there. She keeps wanting

to move and change her citizenship and identity.

It’s interesting how America plays a role in making Chinese people examine their identity in films. Movies about Chinese identity or self-discovery like ‘Full Moon in New York’ (人 在紐約), ‘An Autumn’s Tale’(秋天的童 話), and ‘Farewell China’(愛在別鄉的 季節) from the 80s/90s are often set in America.

These characters struggle with not feeling rooted in Mainland/Hong Kong/Taiwan but also not belonging abroad in the US.

I do resonate with that desire for transformation - feeling unsatisfied with yourself and wanting to hide and reinvent at that time.

“ t he meaning behind my c hine S e name y un Z hi i S that ‘yun’ (昀) meanS Sun, while ‘Z hi’ (知)meanS knowledge. So together ‘ y un Z hi’ S ignifie S S omething like “ S hining knowledge” or “S un S hine on learning.”

t he implication i S having extenS ive knowledge illuminated and enlightened.”

1 The poster of ‘Comrades: Almost a Love Story’(甜蜜蜜) . Copyright belongs to its production company.

2 The poster of ‘An Autumn’s Tale’(秋天的童話) Copyright belongs to its production company.