Editors (Left to Right)

Joseph M C Crawley (he/him)

Emma Macdonald (she/her)

Ayopo Olatunji (he/him)

Ryan Woods (he/him)

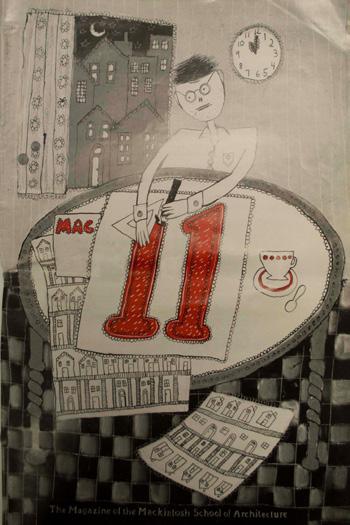

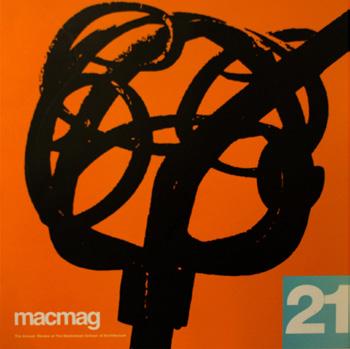

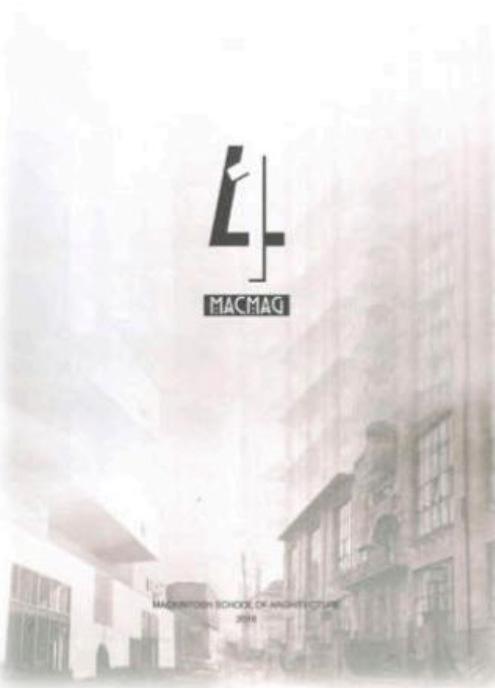

The MacMag has been a proud publication since 1974, which has represented some of the best work from the students at the Mackintosh School of Architecture. We are immensely proud to contribute to a long line of tradition, and present to you all the 49th edition, which showcases exemplar work from the academic year 2023/2024.

As editors, we are united in friendship, with a shared frustration of the current state of our political system, architectural education, society, and the prevalent conflicts across the world. We asked ourselves, how can we give a platform to the voices that aren’t being heard? How can we use our position to talk about issues that aren’t being discussed enough? With this common understanding, we explored the theme of ‘Transgression’, which acts as a polarised form of change, acknowledging the diverse ways architects and designers challenge the status quo, the built environment, and the socio-political sphere.

We have spoken to wonderful people in and around our industry who we believe to be transgressive characters in our field. They have opened our minds in far more ways than we could have ever imagined and have provided great insights into how we can challenge the accepted norms of our time. For this, we are incredibly grateful. Without their time and words, this publication would not carry the same weight.

We would like to extend our thanks to the many students who have submitted their work. The quality and care within the projects we have had the pleasure of featuring is a true testament to the skills and talents of the students at the Mackintosh School of Architecture.

We really hope you enjoy the 49th edition of the MacMag.

The theme of this year’s MacMag is transgressions - and when this was first tabled I asked the editorial team what they meant to explore through this choice. Was it about breaking rules, being a contrarian (old or young), behaving badly or quite what? It lead to an interesting discussion and hopefully a productive focus for MacMag 49.

We have at our core a growing sense of the social and societal responsibilities we respond to, how our behaviours need to provide models for the future that are responsible, ethical, progressive and inclusive. We want to change things for the better, and not just for ourselves as architects.

This is apparent when you look at the projects and the themes students are exploring throughout the school, where core challenges are unavoidable, and where our belief in an ethical, equal and sustainable underpinning to all aspects of practice thinking and output is critical for our futures.

We take it for granted that as a creative, informed, and intelligent community, we know when it is necessary to challenge established positions or orthodoxies, rethink the existing ways of doing things and to ignore or turn our backs on the accepted norm. Retaining the status quo is rarely our ambition, and we consider our ideas to be new, innovative and fresh, but how often are these ideas and proposals truly transformational? Do you have to transgress to make real change? What if we all chose to be transgressive - where would that take us to? I ask these questions to invite and provoke discussion rather than to define a position for myself as for anyone else.

A good and wise friend of the school, Pierre Von Meiss once said to me:

“Pas de change, pas de chance “ - no change, no luck

This edition of MacMag will hopefully help us all to think of the potential of the transgressive, where it figures in your personal behaviours and makeup, and where collectively it might take us to in the future.

We are the Architecture Scotland Alliance for Palestine (ASAP). We are a grassroots collective of active networks and groups operating across Scottish architecture, alongside architects, architectural workers, students, and educators, who have come together through group solidarity efforts and the sharing of educational resources in response to the current situation in Palestine.

We assert that architecture is inherently political. The architectural profession of Scotland, its cultural discourse and education, is tied to and itself a constituent part of wider global political, economical, social and environmental systems from which it cannot be detangled. We take note of the efforts of many in the industry to discuss, support initiatives and enact positive change in regards to wider concerns such as the climate emergency, urban agency and social welfare. Concerns such as these cannot be considered in a discrete Scottish context; our industry is not geographically, politically or economically inert and within it we can make no genuine progress without similarly recognising, discussing and joining global struggles. Despite this, architectural discourse in both Scotland and abroad has been largely silent in regards to the atrocities

committed by Israel in Palestine and against the Palestinian people; ASAP calls for this silence to be broken.

The atrocities committed by Israel, and their enabling by Western states such as the U.K., United States, Australia and Germany, form part of the aforementioned systems from which our industry is inseparable. Israel’s ongoing acts of unfathomable violence in Palestine have claimed the lives of 34,000+ innocent people, injured 70,000+, caused catastrophic conditions of imminent famine and been judged to plausibly amount to genocide by the International Court of Justice. In Gaza, 15 people are killed every hour, of which six are children. In addition to decrying these acts, our industry, its professional bodies, and educational institutions should also be decrying the widespread urbicide and ecocide committed by Israel, which has, in violation of the GenevaConventionrelativetotheProtection ofCivilianPersonsinTimeofWar, indiscriminately destroyed domestic and urban infrastructure while simultaneously targeting crucial infrastructure such as hospitals, schools, universities, places of worship, and sites of cultural and historic significance. Since Israel’s assault on Palestine began 6 months ago, 60% of residential buildings, 80% of commercial buildings and 80% of school buildings have been damaged in Gaza, 267 places of worship have been damaged, and only 11 out of 35 hospitals are partially functional; these figures are modest estimates, and represent the situation prior to Israel’s most recent assult on Rafah in May. At an underestimate in January, more than 281,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide have been emitted by Israel’s bombs; this exceeds the annual carbon footprint of more than 20 of the world’s most climate-vulnerable nations.

Beyond this destruction of architecture and urban infrastructure which has displaced 85% of Gaza’s population, the built environment is being actively weaponised by Israel through: controversial amendments to land law, facilitating the expansion of Israeli settlements; the segregation of land through the West Bank Barrier and its respective highly militarised and dehumanising

checkpoints; and the eradication of Palestinian urban and rural heritage alongside active efforts to limit the agricultural agency for current and future generations of Palestinians. These actions collectively facilitate the ethnic cleansing of the Palestinian people and architecturally materialise Israel’s apartheid regime.

The abhorrent acts described above are being decried globally, including by the Scottish Government, and beyond the indiscriminate acts of murder and destruction, the architectural community should be speaking against the use of architecture as a tool to aid these crimes. As practising members of the architecture industry, we believe it is our duty to highlight such violations, and use any tools or channels possible to support communities undergoing these atrocities, as well as seek to educate ourselves on how our industry is severely weaponised within the war in Gaza, as well as armed conflict in general. Beyond this, the Architects Code of the ARB requires registered architects to practise with care and consideration of the impacts of their work on wider society and the environment. This extends beyond such specificity of the Architects Code to the general duty of care and integrity expected of the architectural profession, in addition to the requirements for lifelong learning and CPD. Such a standard can only be meaningfully achieved if wider global concerns are holistically and honestly recognised as contributing factors, such as Israel’s acts of genocide and human rights abuse, its use of architecture as an apartheid tool in illegal settlements, the covert and colonialist granting of exploration rights along Gaza’s coast to corporate resource giants, and the economic systems which uphold and facilitate these actions.

ASAP represents a diverse cross section of the architecture industry in Scotland. The industry, its professional bodies and its educational institutions in Scotland have relied and culturally benefited from the work of many in this Alliance, particularly in supporting and leading efforts to forefront critical discussions and learning on intersectionality, diversity and climate justice. We mention this to note that rather than offer a veneer of progressiveness, it

is essential that such work is in turn reflected by our industry, whereby we uphold our duty to society, the environment and the world around us. This highlights the importance of understanding the entanglement of urban agency, human rights and environmental justice, all of which are essential to promoting an industry that alleviates inequality, rather than being complicit in amplifying it. Architecture in Scotland should respond properly to the ongoing genocide and humanitarian crisis inflicted by Israel in Palestine, in order to ensure its relevance and position as part of a global society and its struggles. Architecture is political; it cannot be inert.

We hope that through this alliance we will encourage people in architecture, including you, to take action. This alliance welcomes all, and we encourage you to join us.

To find out more, and sign your name to our statement, visit bit.ly/asap asap

We encourage you to use the below resources as a useful starting point to familiarise yourself, and your friends and colleagues, with the historical context of the ongoing situation in Palestine, as well its relationship with the built environment.

- HollowLand:Israel’sArchitectureof Occupation, Eyal Weizman

- DividedCities:Belfast,Beirut,Jerusalem, Mostar,andNicosia, Jon Calame and Esther Charlesworth

- CityofCollision:JerusalemandthePrinciplesof ConflictUrbanism, Philipp Misselwitz

- EnvironmentalWarfareinGaza:Colonial ViolenceandNewLandscapesofResistance, Shourideh Molavi

- The open access teach-in materials of Systems Literacy(Slow Factory) and TheArchitecture ofSettlerColonialisminPalestine(The Funambulist)

- The wider work of Architects for Gaza, Forensic Architecture and The Funambulist

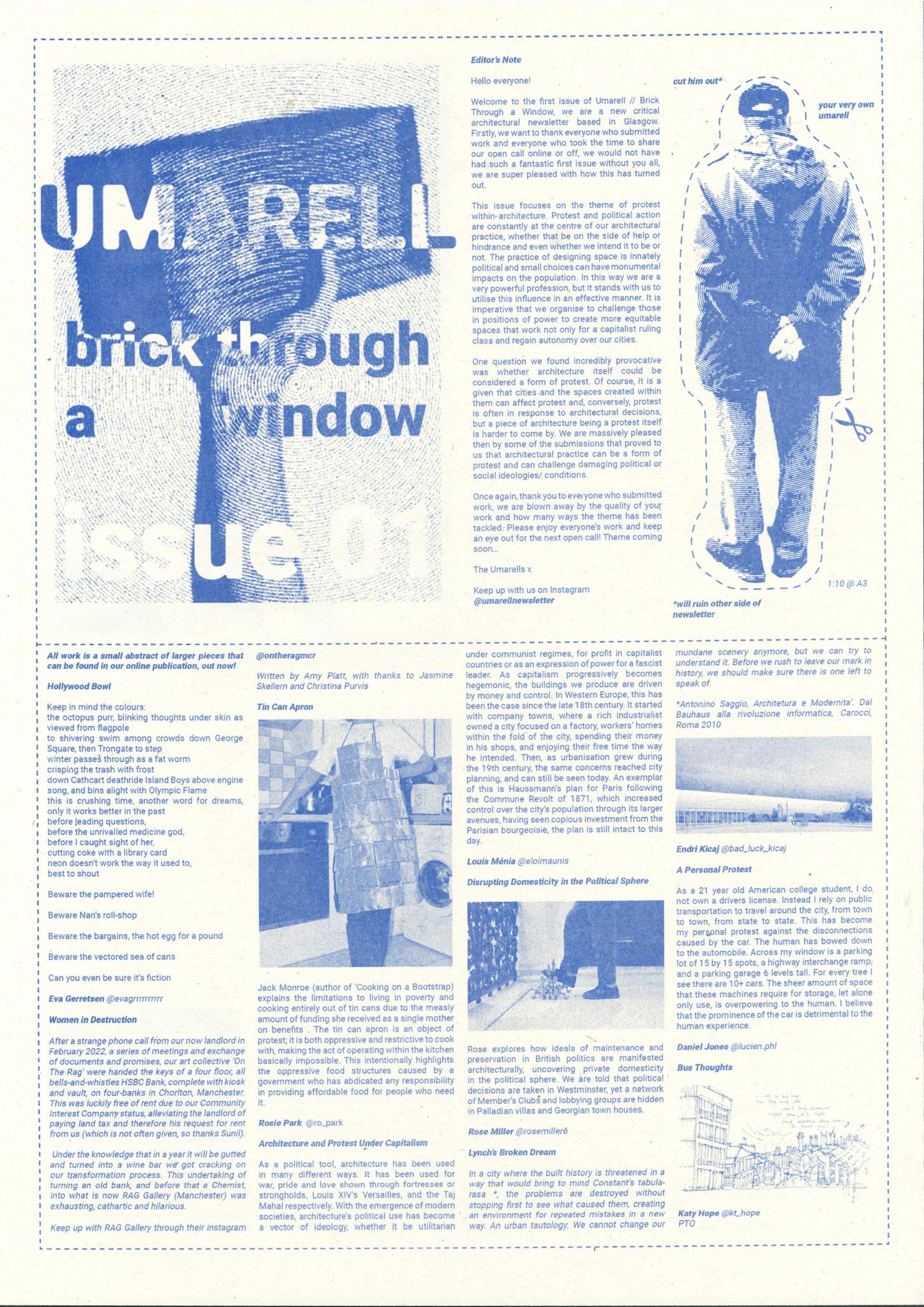

This year’s edition seeks to explore the theme of transgression. By definition, transgression is an act that goes against a law, rule, or code of conduct; an offence. However, the process of creating this year’s edition has shown us that the term is a lot more nuanced in its application and transgressive acts can take on many forms. We interpret transgression as a polarised form of change, acknowledging the diverse ways architects and designers challenge the status quo, the built environment, and the sociopolitical sphere.

In this edition, we look to explore ways in which the arts and architecture are critical of practice, education, and politics by creating new ways of living and working through systematic change.

A decade on from the independence referendum, Scotland has evolved into a much more politically engaged country which continues to feel the effects of a post-Brexit hangover. Glasgow, in particular, upholds its proud reputation of being a hotspot for cultivating political activism and championing social justice for all.

Taking inspiration from the city we all share, we explore the questions...

When do you choose to be transgressive?

How do you choose which form of transgression is appropriate? How do you sustain it?

Transgression addresses a multiplicity of contemporary notions about what architecture is, what it should be and what its future might be. We hope this edition will act as a catalyst to continue the discourse started in this publication.

MacMag 49 stands in solidarity with Palestine and condemns any form of oppression

Conversation With...

at The University of Liverpool

Author of ‘Architecture: From Prehistory to Climate Emergency’ & ‘Raw Concrete: The Beauty of Brutalism’

MM49:

Could you kindly introduce yourself?

BC:

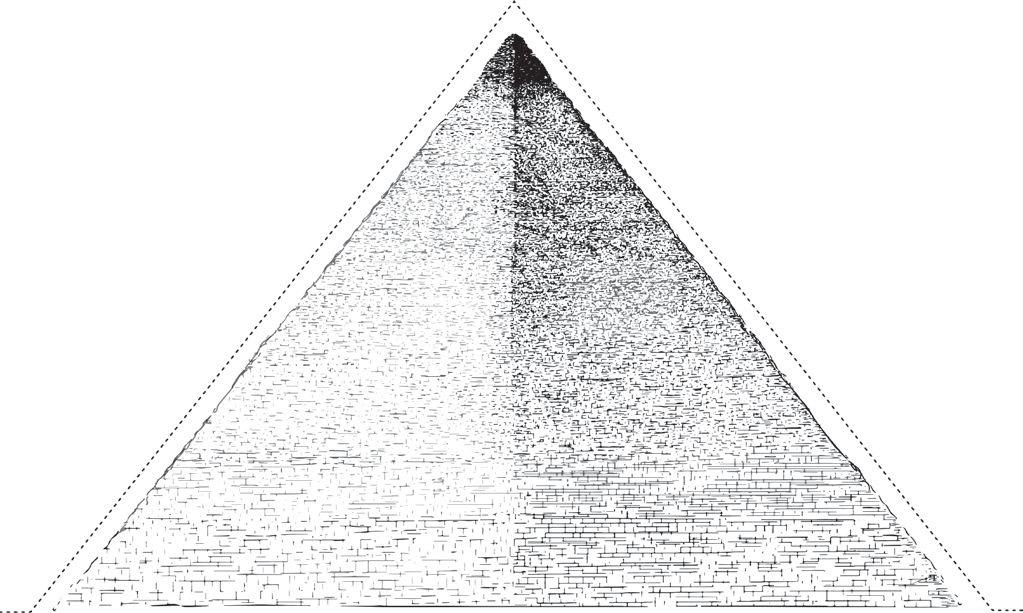

I’m Barnabas Calder, a Senior Lecturer in Architecture at the University of Liverpool, although I was, for five extremely happy years, a lecturer in Architecture at the University of Strathclyde. I absolutely love Glasgow - it’s a very hot contender for my favourite city on earth. I’m a historian of architecture and my research started out on Brutalist architecture, the architecture of the 1960s, heavy concrete stuff, particularly the works of Denys Lasdun, which I’m returning to finish my complete works soon. A few years ago, I was asked to do an introductory history of architecture that would introduce readers to important issues now. I was thinking about what the important issues now were and I thought about energy as being the biggest issue in contemporary architecture because of its role in driving the climate crisis. I did some back-of-the-envelope calculations about the Pyramid of Khufu, the biggest of all ancient monuments and discovered that all the labour that went into building amounted to a very, very small amount of energy in modern terms. I realised that was a very big story, so I started reading all the energy history I could and it took me into this first book to try and take energy history as the basis for an architectural history. I’ve been teaching that at Liverpool for some years now and trying to spread the word about it as wide as I can.

MM49:

In your book Raw Concrete: The Beauty of Brutalism (William Heinemann, 2016), you tell a very touching story about your brutalist pilgrimage to Hermit’s Castle in Achmelvich. You state that it is ‘one of the most evocative and beautiful buildings you have ever seen.’ Could you tell us of a similar structure or building that has the same effect on you, which is carbon-friendly and climate-conscious?

BC:

The thing that’s incredibly cheering about history from this point of view is that there’s an enormous range of buildings that are deeply sustainable, built with very local materials, built using very low heat input and built with an acute awareness of local climate and other issues like flooding. In Britain, you have to go back 400 years to get to these buildings. Around most of the world you can go back somewhere between 50 years and 150 years to get to them. From there, you get back, as far as architectural history can take you, 14,000 years of traceable human constructions. All of that is profoundly sustainable, all of the entire output of that period before the modern adoption of fossil fuels.

Every time I see a pre-1600 building in this country, I get that feeling of, ‘Oh, look at that, that material is from just at the end of the garden, that material was cut down just to make this building a few hours before it went into place and then they grew another tree to replace it and that material is just brought straight from the quarry not far away by sailboat or oars.’ It’s so universal around us in the older buildings but both you in Glasgow and I here in Liverpool lack many pre-industrial buildings to look at in our immediate surroundings. We’re both in cities that boomed so spectacularly under the influence of coal that you have to get out of the city or go and see the cathedral in your case, or one Tudor manor house in my case that is built before that, everything else is built on coal I think.

MM49:

We have seen a recent shift in architectural education to include environmentally conscious design teaching. As a Senior Lecturer at the University of Liverpool, do you think that students graduating now, compared to 5 years ago, are more equipped with the ability and the commitment to face the climate crisis?

BC:

This is a really important question. I think the answer is that it depends on the student to quite a large extent. At the moment, we are allowing people, and to some extent helping them, to produce very sustainable designs. But the tail of people who don’t want to is not being given much of a chase into doing so. I’ve heard quite a lot from students that if you design something really quite small,

where you’ve done a spectacularly good job of researching very local materials, very low carbon techniques, or reusing an existing building in a truly credible and sustainable way, you will struggle to do as well as someone who’s designed a kind of Archigram style megastructure but claims that it’s timber. That is very concerning and it’s something that requires the staff to want sustainability as much as the best students already do.

I always used to really appreciate about architecture schools the fact that they’re not very good at enforcing a single orthodoxy. I liked that heterodoxy. I find it quite frustrating. It’s not because I have a megalomaniac desire to enforce an orthodoxy, it just doesn’t make sense to be training people to produce enormous concrete buildings at a point where we know how ecocidal those are. Yet that’s still what a lot of architecture schools are doing.

MM49:

You are well renowned for your research and investigations into architectural history and energy. Your calculations and statistics prove to be very insightful in our education. Could you elaborate on how you preach to the masses about this important information? How do you make people listen that don’t want to listen?

“So, at the moment, the left-right culture war is the biggest threat to effective climate action.”

BC:

Huge thanks for saying it’s been useful in your education in some way because that was a big aim for the book and it came out of teaching architecture students! In terms of getting the message out more widely, you can’t talk to people who absolutely don’t want to hear it.

I think one of the most important things and something that I struggle with myself, is not to package environmental sustainability tightly with every other good idea and try and get them all through at once. What you end up doing is producing a kind of association that’s dangerously prevalent now between a particular political position and a particular environmental position, which means that overwhelmingly only people on the left at the moment are willing to be publicly outraged by our dismal performance on sustainability. If we could rapidly make everyone members of the left then that might become a viable option for achieving sustainability, but since we can’t, then packaging it in such a way that it gets rejected along with other things that the centre and the right don’t welcome is environmentally disastrous.

So, at the moment, the left-right culture war is the biggest threat to effective climate action. And it’s insane because whilst a lot of right-wing policies make selfish sense to the people who pursue them, their hostility to a habitable planet doesn’t make sense even to them, even to the handful of billionaires who are able to buy their way out of everything.

It’s in literally nobody’s interests for the environment to collapse. At the moment it feels as though it’s become a political issue, as controversial as redistribution of wealth. I’m in favour of redistribution of wealth. I actually think it would be very conducive to resolving the environmental process. But if you start with saying to people, ‘We have to redistribute wealth and carbon’, then they say, ‘Fuck off, I’m not redistributing my wealth’ and they don’t hear the bit about carbon. If you say, ‘Which of these two futures do you want for your great-grandchildren?’ and you set out the probable scenario if we carry on as at present and a scenario if we sort this out, that’s a very different proposition. We can appeal to selfishness, which is always - and not inappropriately - an important human motivator. So it’s important not to bundle

stuff together and not be right-but-annoying all the time - not come across as endlessly smug, which is something really difficult when you know you’re right! But in those discussions over the dinner table with the uncle who voted for Brexit and who thinks that everything that’s wrong with the world has to do with illegal immigration, try to keep as calm as you can when discussing the environment. It’s better that people who are wrong about everything else take some climate action rather than they don’t do something. The key thing is fighting against one’s own culture war instincts because we do worsen it from our side as well, even though we’re right.

The great advantage we have in pushing this to people who are a bit currently unconvinced and think it all sounds like dangerous change is that the conservative instincts that make them worry about change also make them love old buildings. Old buildings are the answer to a lot of these questions, so rather than saying, ‘We need to radically change everything’, you say to them, ‘We need to go back to the way things were’ and you say the right thing for your client. If you’ve got a very future-minded client, you say ‘We need to go forward into this exciting, sustainable renewable energy future’ and if you’ve got a client who’s a bit wary about it, and thinks that most modern buildings are ugly, you say, ‘We’ve got to rediscover our traditions and get back to our roots with this kind of architecture’ and both statements are true. It’s just a question of presenting the side of it that will make the clients, or the person you’re discussing it with, see the arguments and start to lose that hostile, immediate wince reaction that stops them from engaging with it in the first place.

MM49:

We are aware that you and Professor Florian Urban have been conducting some research into embodied energy as a metric. Should embodied energy also be embedded into our teaching to better understand the environmental implications of our built environment?

BC:

An assumption of energy scarcity needs to be the norm. Therefore, the solutions that are theoretically decarbonisable but very energy intensive are less desirable than ones that are also lower energy consuming. Until we have such enormous production of renewable electricity without negative environmental implications, we should not squander energy on things such as ever using aluminium. As things stand, aluminium has almost the same carbon footprint as the entire continent of Africa. We continue to use it all the time on buildings and say, ‘Oh, it’s got a very high content of recycled aluminium.’ Well, that doesn’t make it OK: it’s still energy-intensive to recycle. There’s still demand for new stuff to be produced. If you use some of the recycled stuff, someone makes more. We’re not in a situation where recycled aluminium is like local stone and it’s just a material that you make use of when it happens to be around. We’re in a situation where it’s being produced on an enormous scale from virgin bauxite.

MM49:

Following that, based on the research for your book Architecture: From Prehistory to Climate Emergency (Pelican, 2021), how have you observed architects navigating the tension between innovation and tradition, especially concerning energy consumption and sustainability in architecture?

BC:

There’s a very wide spectrum of practice from totally apocalyptic four-degrees-ofclimate-change-by-the-end-of-the-century practice, usually with the word sustainable shoved in front of it on all their literature, through to people who are genuinely trying very hard to do the right thing and have credible claims to partially achieving it. I think the word tradition is really interesting in that question because the concern is the fossil fuel tradition. People all around the world since the 1950’s have been deliberately and systematically taught a

concrete and steel basis for architecture and the HVAC norms of North America where the building, to be ‘prestigious’, must be 21 degrees all the time, whether it’s in Anchorage or Dubai. It should also look really glassy outside, which is insane in almost all climates. Next to nowhere is a glass-faced building without shading a good solution to embodied or operational energy use. These norms, which have become the worldwide tradition of architecture, are exactly wrong. The traditions we need are the old traditions.

We don’t need to go back to doing exactly what we were doing before, because quite often, there were problems like in preindustrial, pre-fossil fuel Northern European cities, there was quite often a significant problem with fire risk if they didn’t have a lot of local stone. London burned down often enough to mean that the contracts between landowners would say, ‘This is the border between our properties until the next fire and then we’ll rationalise it to get all those kinks out and have an easier party wall.’ They knew that at some stage, both buildings would burn down in a catastrophic city fire. There’s nobody who wants to go back to that. There are massive things we can learn in terms of walkability and in terms of material use, with modern fire sophistication. Similarly, around the world, there are problems that aren’t dealt with by just going back in time. Particularly with warming temperatures and increasingly extreme climates, there’s a big band of the world where it’s becoming increasingly dangerous in the hottest weather, not to have air conditioning. There’s a jump between saying ‘Air conditioning is a necessity at times for health’ and saying ‘All buildings need to be sealed with a 21-degree target.’ Air conditioning down to 30 degrees from 40 degrees is an awful lot less energy consumption than air conditioning from 40 to 21. It gives you the health effects you need and takes some of that humidity out, where the most dangerous effects from extreme heat come.

You don’t have to cool the entire house but could instead have a safety room, where in the worst times, you will go into the cooler room. In the same way, in cold countries in the coldest times, you gather in a warm room. I’ve noticed that in our attempts to heat our house as little as possible, I’m usually in the same room as the cat in winter because he and I

have both found the warmest place.

Adapting to use less energy is much pleasanter than trying to adapt to runaway climate emergency. We need to meet the needs of the present through renewable energy and older building traditions, and escape the habits of fossil fuel architecture. Fossil fuels made carbon-intense heat cheap, and labour expensive, so wherever possible coal or oil were swapped into processes to cheapen them.

“What the hell are we doing using this dangerous, carbon-intense junk?”

This results in a grotesque situation where we specify now plastic and aluminium claddings at huge embodied energy cost, which are only expected to last 30 years or so. If you thatched the facade instead you would have sequestered carbon, achieved a longer design life and, as the appalling tragedy at Grenfell Tower showed, in a fire it would burn slower and with combustion gasses that were less rapidly lethal. What the hell are we doing using this dangerous, carbon-intense junk?

MM49:

This is a topic we’ve been discussing as a group, where does the responsibility lie? Should we consider taking on jobs when we don’t agree with the ethics and morals with the client, by taking on that job are you then complicit? At the end of the day, an architecture practice is a business and if you turn it down, someone else will get the project. Or should we be turning down more projects by taking a stand?

BC:

Stay in architecture. The most powerful thing you can do to help is to remain an architect whilst continuing to care about the ecological emergencies. It’s not easy. Some get ground down by the guilt and cognitive dissonance of knowing the situation and carrying on having to be involved in a process that they know is harmful. We need you there as more senior architects as soon as possible, where you can make more difference. If all young architects refused to have anything to do with any kind of architecture practices that were doing the wrong thing that would potentially put pressure on, but how are you going to achieve that? Given the quantity of architects trained around the world, it’s not achievable and doing it on your own doesn’t make any difference. It makes more of a difference to get in there, do what you can at every stage, maybe walk out over things that are particularly bad. I can’t really understand why any ethical young architect would still be working for Fosters and Partners or BIG at this point given their prominence in pursuing carbonintense new construction on a very large scale. Too many leading architects are doing the most harmful thing you can, which is to actively mislead the client about how sustainable options are in carbon terms. That is an astonishingly culpable thing to do. Architects, of course, do not control what gets built or how, they can only propose design solutions. If an architect makes an accurate environmental case for retrofit with some timber extensions and a client opts to demolish and replace with reinforced concrete that’s on the client. If the architect tells the client that a new reinforced concrete building is a sustainable solution then the guilt lies with them for the outcome.

MM49:

Before 2035 Glasgow City Council wants to increase the city centre by around 40,000 people. How do we tackle a city such as Glasgow with a high stock of listed buildings such as the tenement and many national treasures which are on the brink of extinction, such as the Mackintosh building, whilst using form follows fuel and maintaining great climate and energy consciousness?

BC:

It’s a really interesting and important question. The challenge starts at the setting the intention stage. What Glasgow needs to do is not ask, ‘how can we be more sustainable while doing exactly what we want?’ But should be asking ‘how do we want what is sustainable?’. The question that contemporary business and government usually ask is ‘how do we cut carbon a bit whilst doing what we want to do anyway?’ The question they need to ask is ‘how we live good lives with zero carbon emissions?’ They’re very, very different questions. So a 10% carbon saving is seen as being an amazing achievement at the moment but actually, most of those savings are at least partially fictional and accounting tricks. Even if they were making 10% carbon carbon savings, that would be totally inadequate because we know we need to be at zero. We’re currently at the world’s highest ever emissions and going up every year, so the way we’re doing this is massively wrong. The challenge is to want to get it right because a lot of the time, the solutions are incredibly easy and very cheap but just not very appetising.

For example, a solution to reducing car use - is not to use a car. The solutions are all already there. Some people have mobilities which necessitate car use. The rest of us could make almost all our journeys by other means. There are a few rural contexts where that will be really difficult, but an overwhelming majority of the British population could give up their cars today and get by fine. I’m aware that it is not appetising. It doesn’t enable you to do all the things you do when you have a car but it does solve the problem really simply. A lot of these things are like that, we have a problem with our carbon emissions from buildings, so burn less gas to keep warm, live colder. Again, some people have specific health conditions that mean that it’s not safe for them to do so, so they can continue to keep at least one room at a level where they’re able to keep their health safe. But for the rest of us, we can live colder.

People keep saying we can’t move to renewables because they’re intermittent. Well, the answer is we have to move to renewables, so how do we live with an intermittent energy supply? The answer is that you have certain things that are

sacrosanct like life support machines and heating for people who desperately need it etc. You have other things that can become intermittent along with the energy supply. So you charge your devices and run your washing machine at points where it’s windy or sunny or where the tidal energy is adequate. You run your industries at points where the renewables are abundant and then they just go dormant when it stops and everybody goes home and draws a picture or plays with their children. It’s not hell, it’s not a terrible world. An awful lot of the things that people are worried about are made-up problems that we’ve chosen to invent for ourselves through our economic system.

“Move the people around, not the buildings.”

When everyone wants to solve it, the solutions are much simpler than people think; it’s much less devastating than people think. It’s in everybody’s interest to achieve it. It’s only a matter of breaking the sense that it’s insoluble and then we can do it. But it’s not a question of looking at Glasgow’s existing policy that’s conceived around fossil fuel norms and trying to find something ingenious enough to fully fix the problems they throw up with it. It’s a question of thinking, ‘what should Glasgow look like as a fully sustainable city?’ The answer is almost all its buildings should be the ones that it already has, because it’s got loads and loads of buildings. They should have a lot of care given to their gutters because the rain is already a problem for Glasgow buildings and it’s getting more intense. They should have modest, carefully-conceived low-carbon interventions to improve insulation and air tightness where possible. But keep the buildings and put a wooden extension on the roof of the ones that can take it. Move the people around, not the buildings.

One person’s transgression is another person’s orthodoxy

Stage Leader

James Tait

Co-Pilot

Georgia Battye

Studio Tutors

Sam Brown

Maeve Dolan

Alan Hooper

Iain King

Robert Mantho

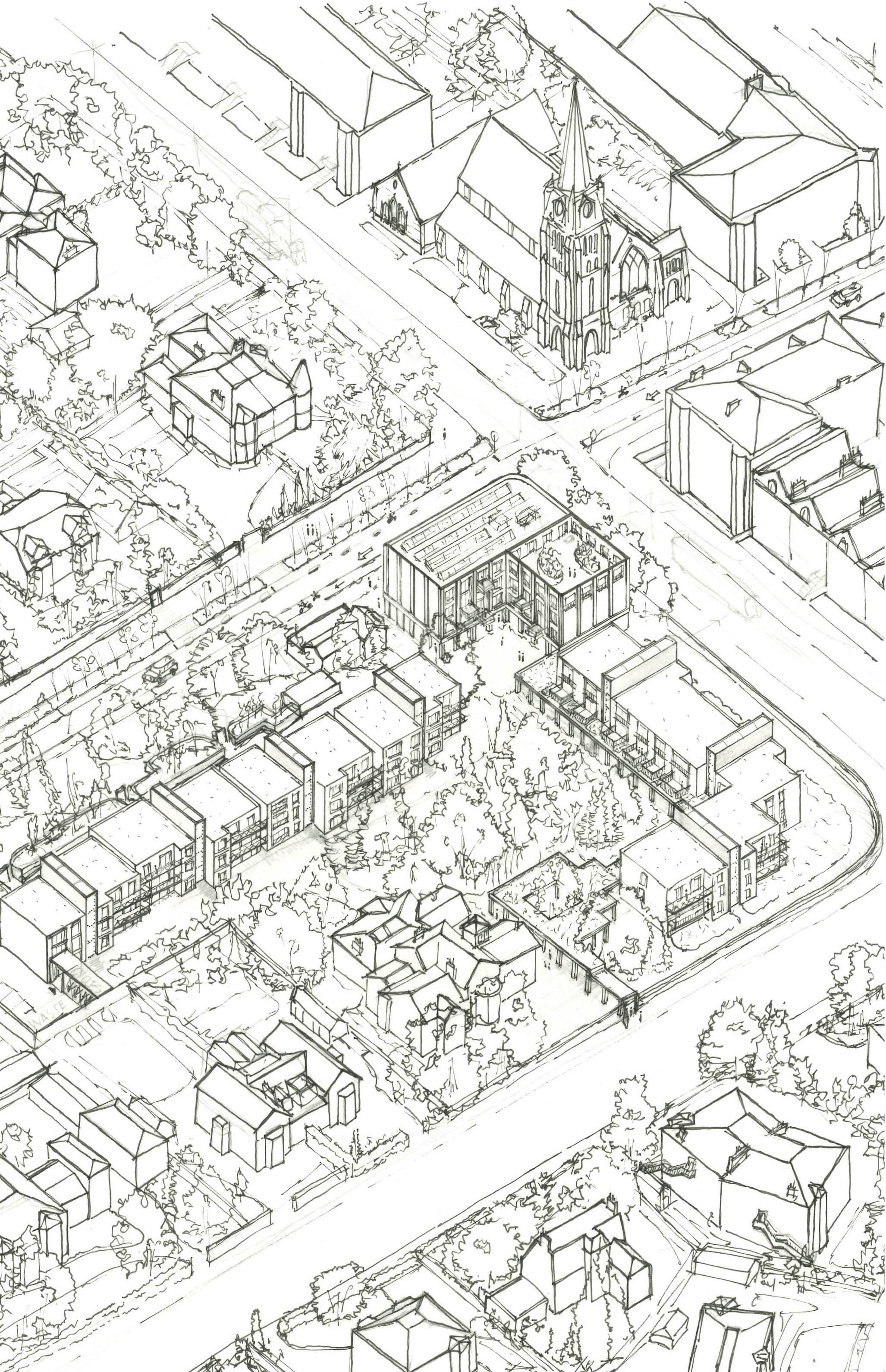

The aims of Stage 1 are threefold: To train hands in new ways of architectural observation, representation, and exploration, to open minds to the challenges and possibilities of being an architect in our current times, to embed students in the studio culture of the Mackintosh School of Architecture and wider Glasgow School of Art.

To achieve this aim, Semester 1 focuses on equipping students with the good habits required to achieve high standards of architectural production, exploration, and enquiry. Semester 2 builds on this foundation allowing students to develop, play, and explore with increasing agency and autonomy as the year progresses.

Through the course of the year we introduce students to: New ways of seeing architectural space, various ways of representing architectural ideas and aims, through drawing, modelling, and verbal communication. The analysis and appraisal of precedents and case studies, with a particular focus on the vernacular, understanding place and space, through mapping and site.

Basic concepts around the reuse and adaption of buildings, particularly in response to the climate crisis. Distilling and editing work to be clearly understood and appreciated by others, working and collaborating with others within MSA and the wider GSA. Developing designs in detail, applying knowledge gained in Architectural Technology.

As part of a wider shift in the undergraduate years to engage with rural environments, the year has been embedded in the Isle of Skye. We organised a series of talks from local makers, artists, and architects forging new links between the school and the local community. Investigations of Struan Jetty (on the west coast of Skye) laid the foundation for two projects - an adaptive reuse of a listed stables building and the establishment of a small community of dwellings - located on this same site. The study of place has been essential in allowing our students to test their analyses and ideas in-situ.

Ultimately, students by the end of this first year will become critically engaged, technically skilled, and independent free-thinkers ready to progress to the next stage of their architectural education.

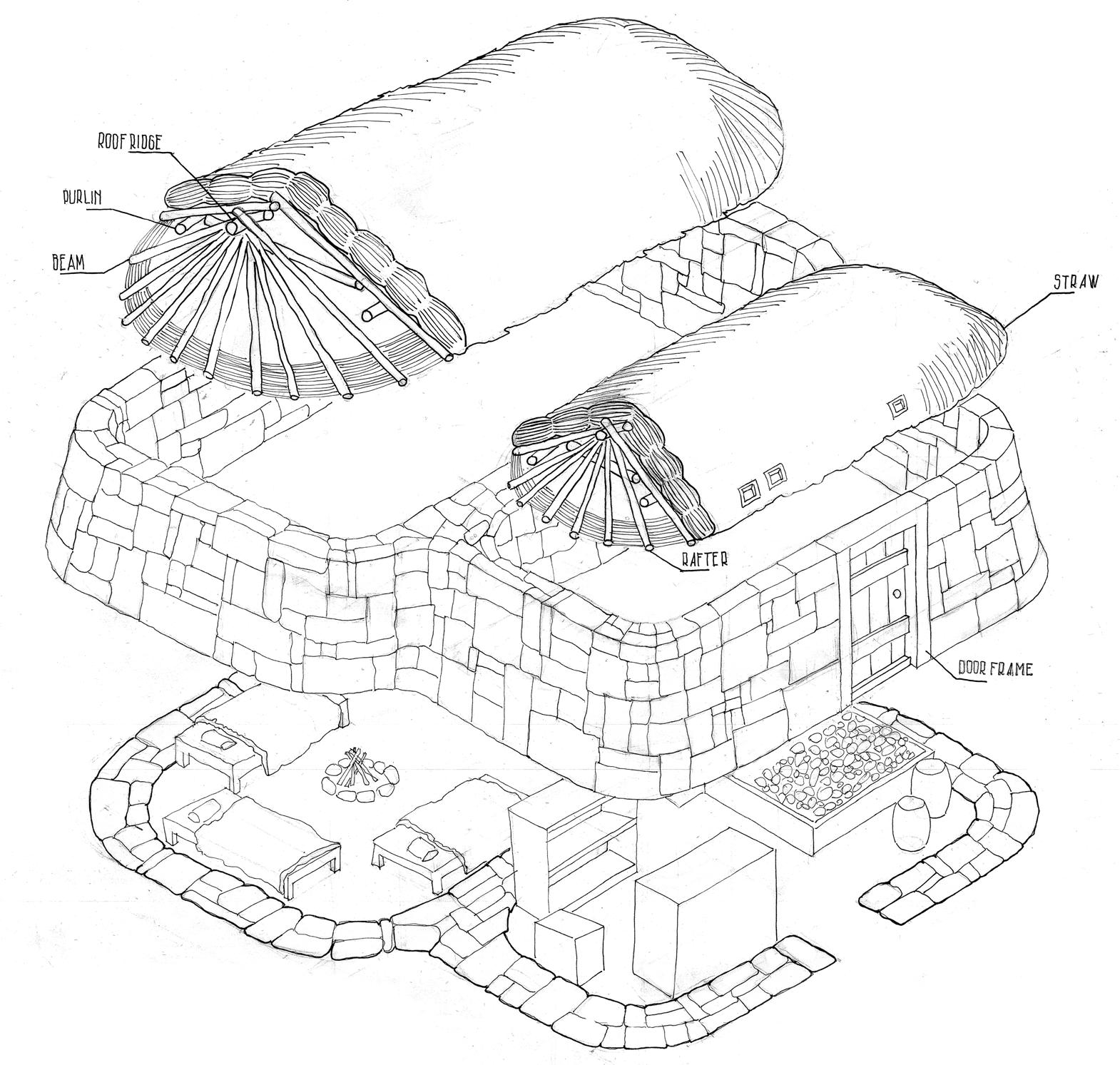

This project was to introduce us, as future architects, to primitive architecture. Primitive architecture is the beginning of the architectural profession as such. The main ideology of this project is: “It is estimated that only 1% of dwellings around the world have been designed by an architect.”

To me, this means that even if architecture was designed by the people and not by a professional, it is not far from being bad and impractical. We were offered to study several examples, and after choosing one particular one to study in depth and understand all its solutions, my choice fell on the Black House. I immediately found this example very interesting because compared to the others I noticed details that were designed to make it comfortable to live in. These details drew from the terrain and weather conditions that surrounded the inhabitants and creators of this architecture.

Responding to the brief “Material matters” whilst being conscious of designing in the anthropocene, I was tasked with designing a space for a maker of my choice, working with the existing ruin walls of a site I’d visited in the Isle of Skye.

We are all frantically searching for innovative solutions to the impending climate crisis when really we already have the answers. Yet nobody wants to listen to them. The answers are written in the land and known by those who are wise enough to listen to it. As Robin Wall

Kimmerer beautifully said: “If time is a turning circle..... the footprints of First Man lie on the path behind us and on the path ahead.... All things that were will come again” Bring nature back. That’s what I wish for my design to achieve. Blur the lines of urban and wild. They are not two separate ideas but one whole that have separated and are struggling to find their way back to one another.

My proposal looks to the land for the answers. Material matters and wood is at the heart of the form, function, heating and aesthetic of my design.

The material journeys through my design as it would in nature. Sensical and cyclical, connected to the land. The pruning and upkeep of the living structure provides my maker, a hand-tool woodcarver, with material to work with, any scraps are saved as fuel for the fire. An external sleeping space, inspired by vernacular dwellings, separates work and rest and further integrates the structure with the landscape. Finally a glass roof allows for the seasons to be felt from inside the workshop, bringing the outdoors in.

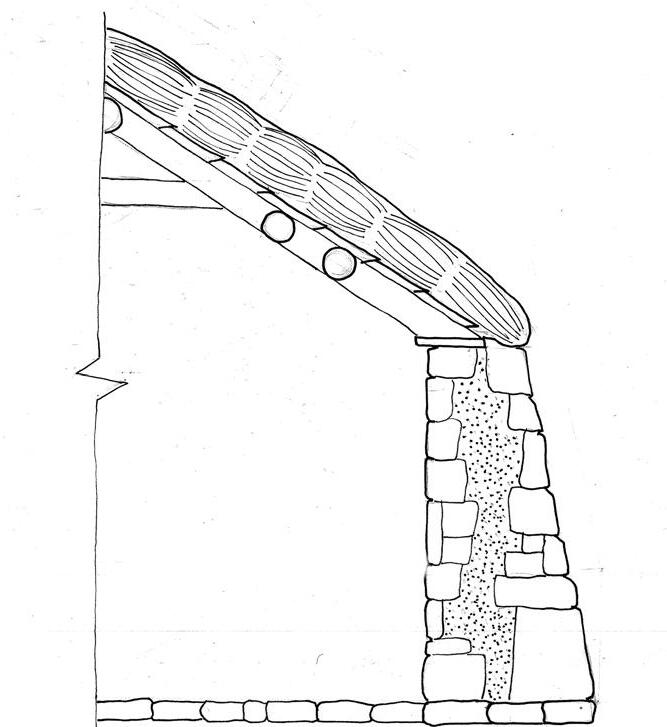

Having visited the site of an old ruin in Skye, we were given the brief of refurbishing the site into an artist’s residence and studio.

Local artists and historians lectured us on their practices, the history of Skye, and its current social climate. I chose to build a carpentry studio as there is a sustainable sawmill in Skye that can supply the development and carpentry practice within it. Due to Skye’s history of colonial rule and Highland Clearances, I chose to maintain the old stone structure

and rusted metal barn, preserving the history of the site.

I focused on designing a moving roof for the studio space to utilise the natural resources of the site. As the carpenter on Skye specified that they preferred to work in natural light, this roof has a glass ceiling with blinds operated by pulley systems. This controls glare and channelling winds, providing ventilation in the space. I aimed to conserve the site, in appearance and by having

as little environmental impact as possible. This design challenges the concept that a building must protect inhabitants from the environment and instead works with the natural elements available on Skye to fit into the landscape.

Key

[1] 1:50 Model w/Pully System

[2] Kit of Parts - Roof Detail

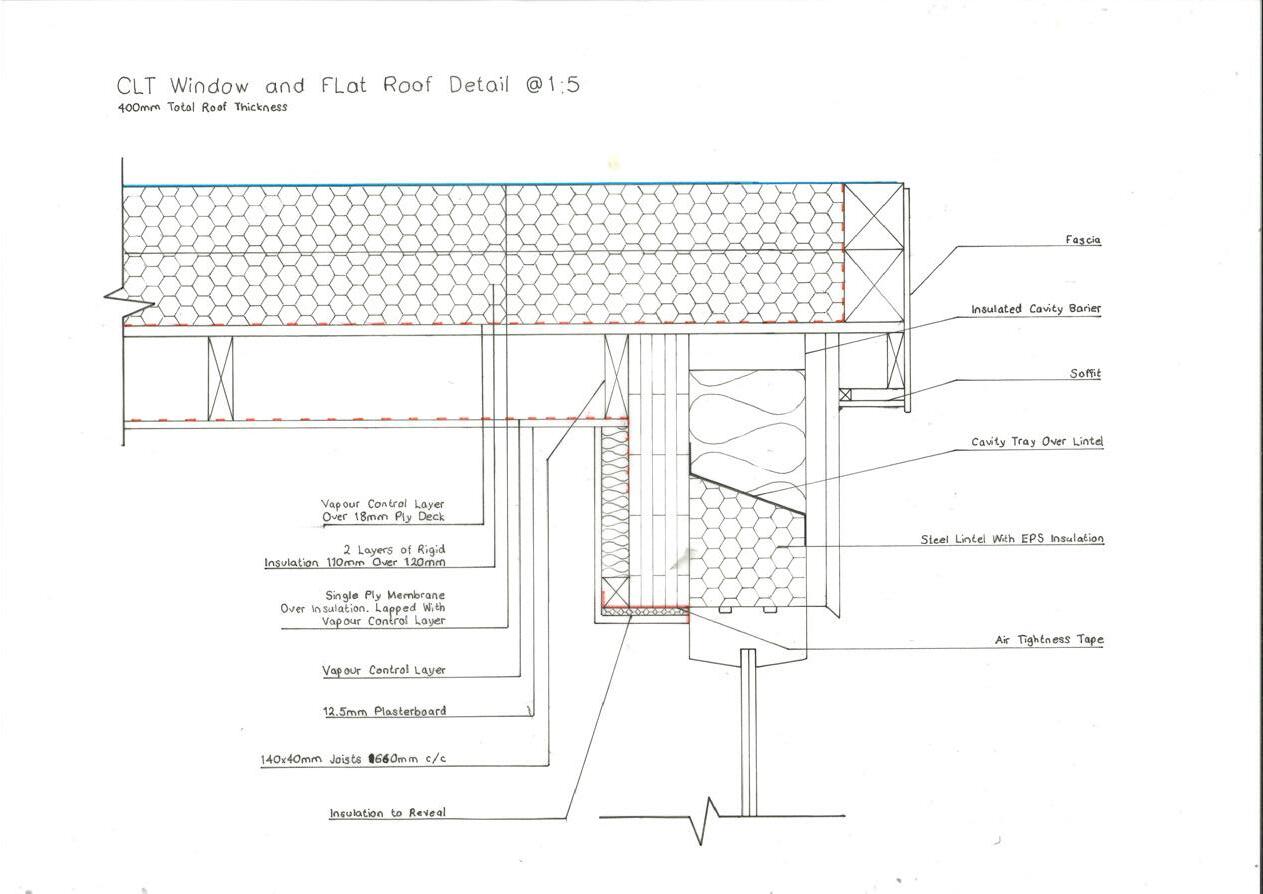

Adapt and Detail, aimed at extending the life of an at-risk Scottish stable house, located in Struan, Isle of Skye. The derelict building was to be renovated into a small-scale timber workshop, that could also facilitate some living quarters. The proposal required us to provide an architectural answer to the damage that the Anthropocene has inflicted. This

Our second project of stage one tasked us to consider and question how we define architecture. Asking us to think about the home and how we inhabit domestic space, as human beings, more universally and analytically. Researching domestic vernacular typologies in different environments helped broaden our understanding of how structures came to be and what we can learn in the modern age from a time when communities were much more connected to their culture, place, and ecology.

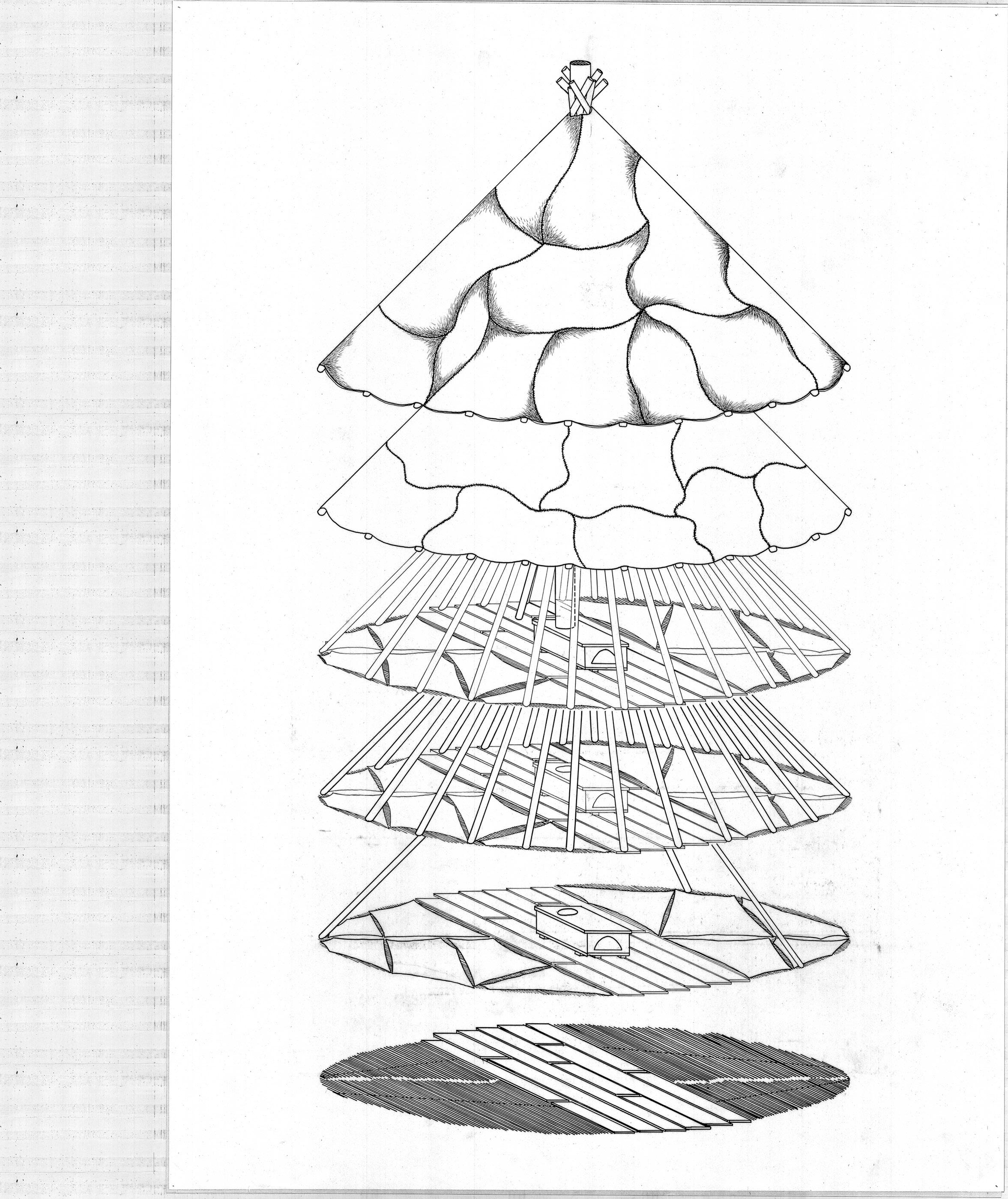

The Siberian choom or chum dwellings I have illustrated are temporary dwellings used by the nomadic Nenet People, still used today. The chooms are purposely designed to be easily constructed quickly and effectively in cold, challenging conditions. The Nenet People migrate north across the tundra every year following the ancient paths of the migrating reindeer. For this reason, it is fundamental they can be constructed and deconstructed every three to five days. To the rear of the choom there is an

imaginary line that points towards the tundra called the Sawein Line.

The Nenet People craftfully utilised the sparse materials they had available to them, allowing them to adapt to the cold winters, successfully displaying what can be achieved using only natural materials. They have transgressed to be able to live in an environment that is harsh and uninviting, an environment most people now would not attempt to pitch a tent in.

Project three presented the unique challenge of retrofitting an existing building situated amidst the breathtaking vistas of the Isle of Skye.

Central to the design process was a deep understanding of the cultural narrative woven into the fabric of the island, as well as a keen appreciation for the surrounding natural landscape. Anchoring the architectural intervention within the context of Skye’s rich heritage and rugged terrain fostered a harmonious integration of the built environment with its pristine surroundings, ensuring a design solution that resonates with both the locale and its inhabitants.

Stage Leader

Kathy Li

Co-Pilot India Czulowska-Burns

Studio Tutors

Graeme Armet

Rob Colvin

Joanna Doherty

Colin Glover

Nick van Jonker

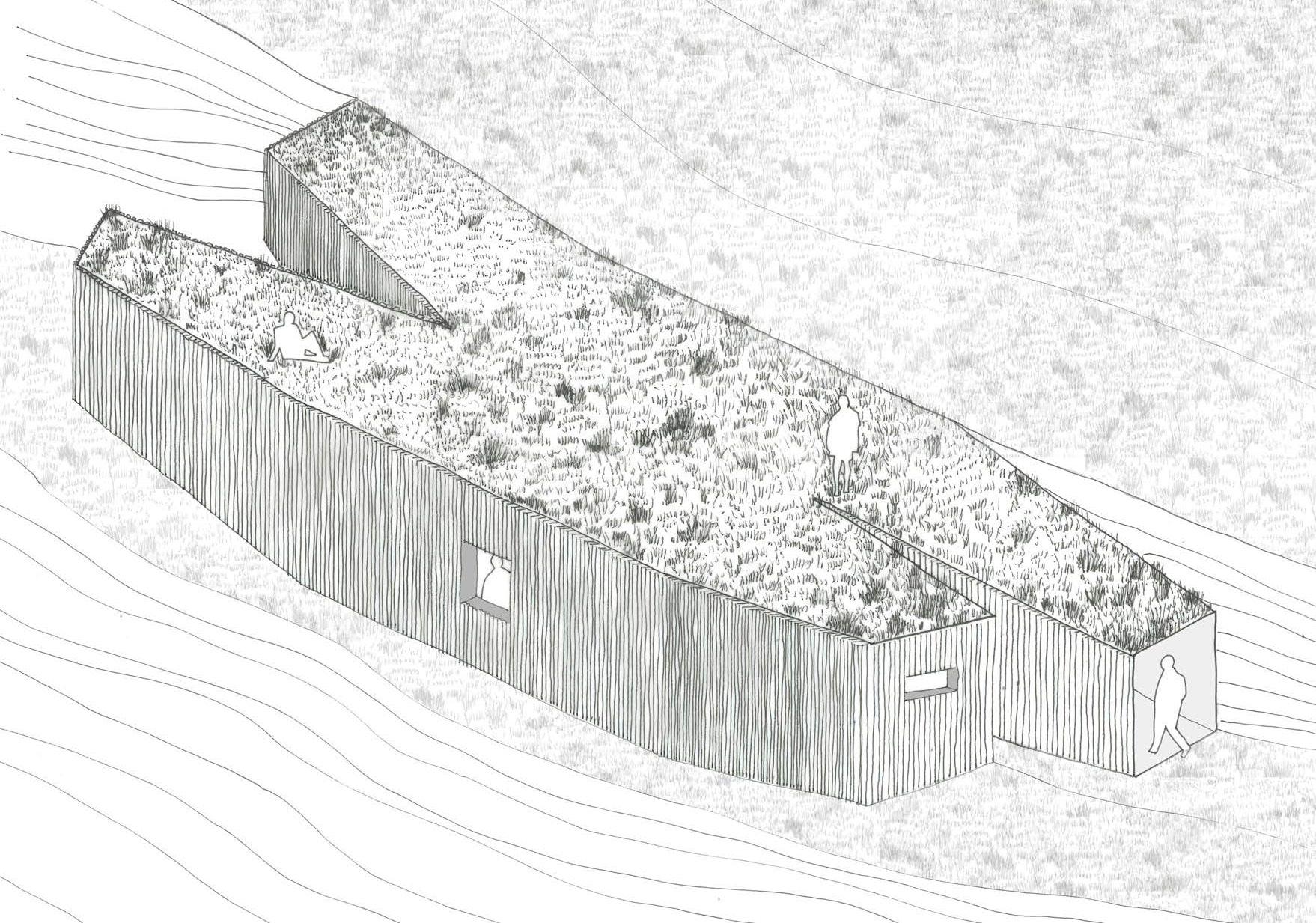

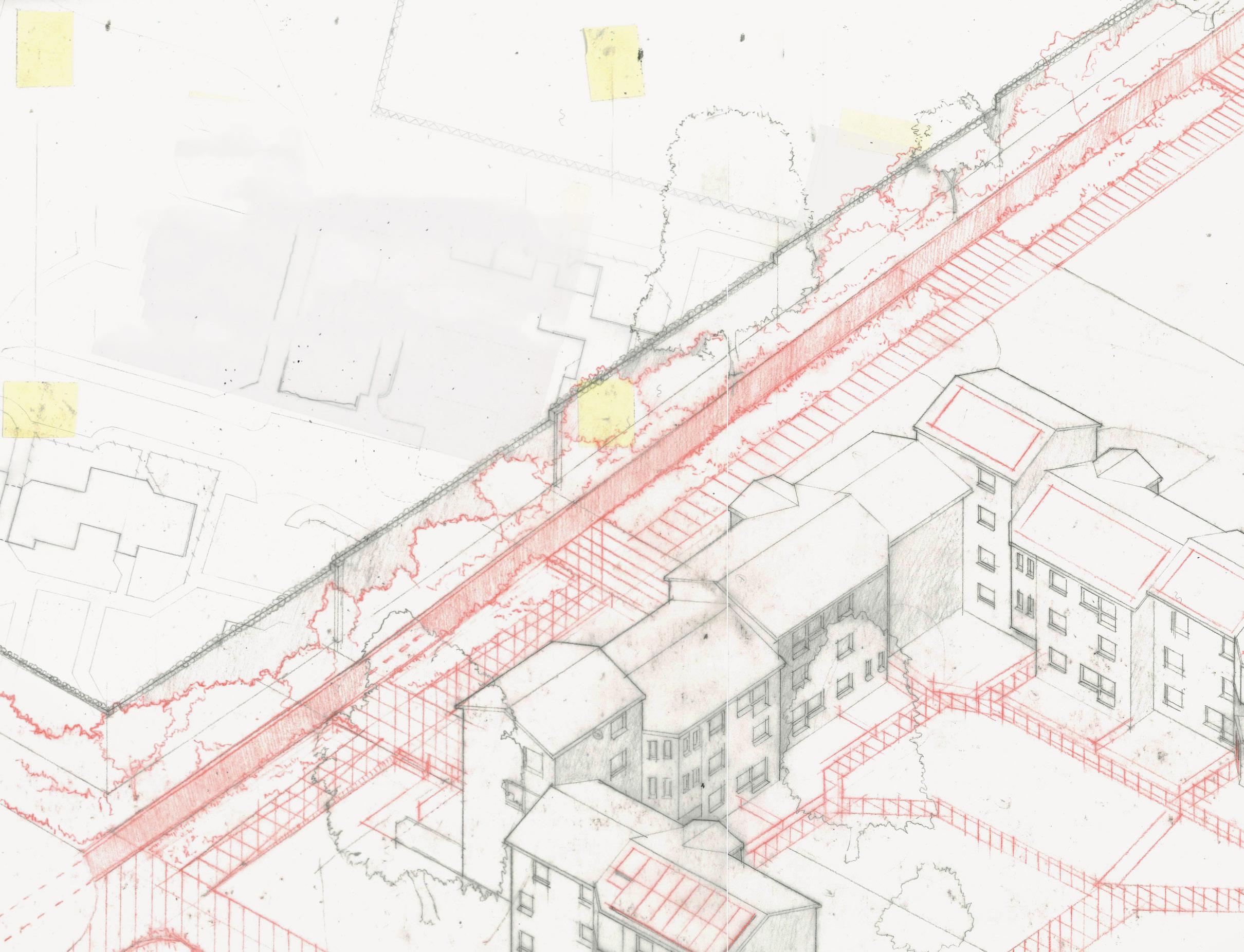

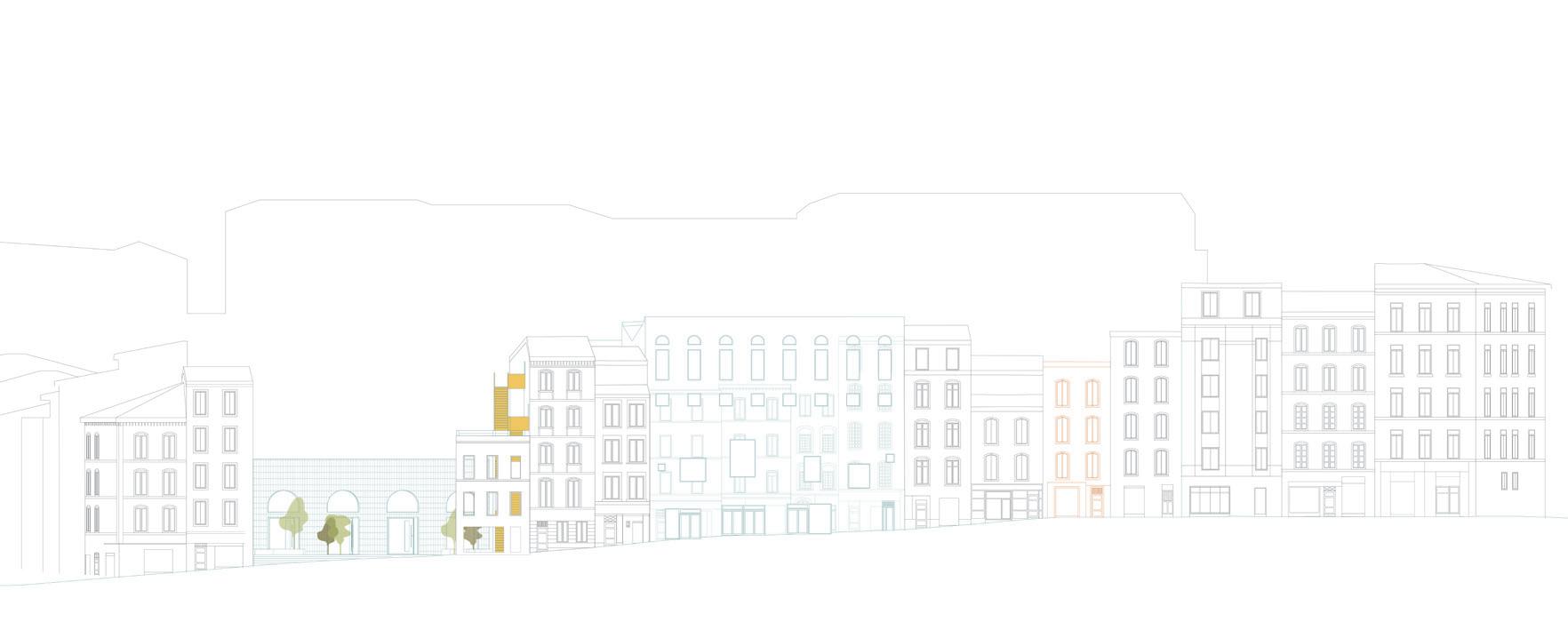

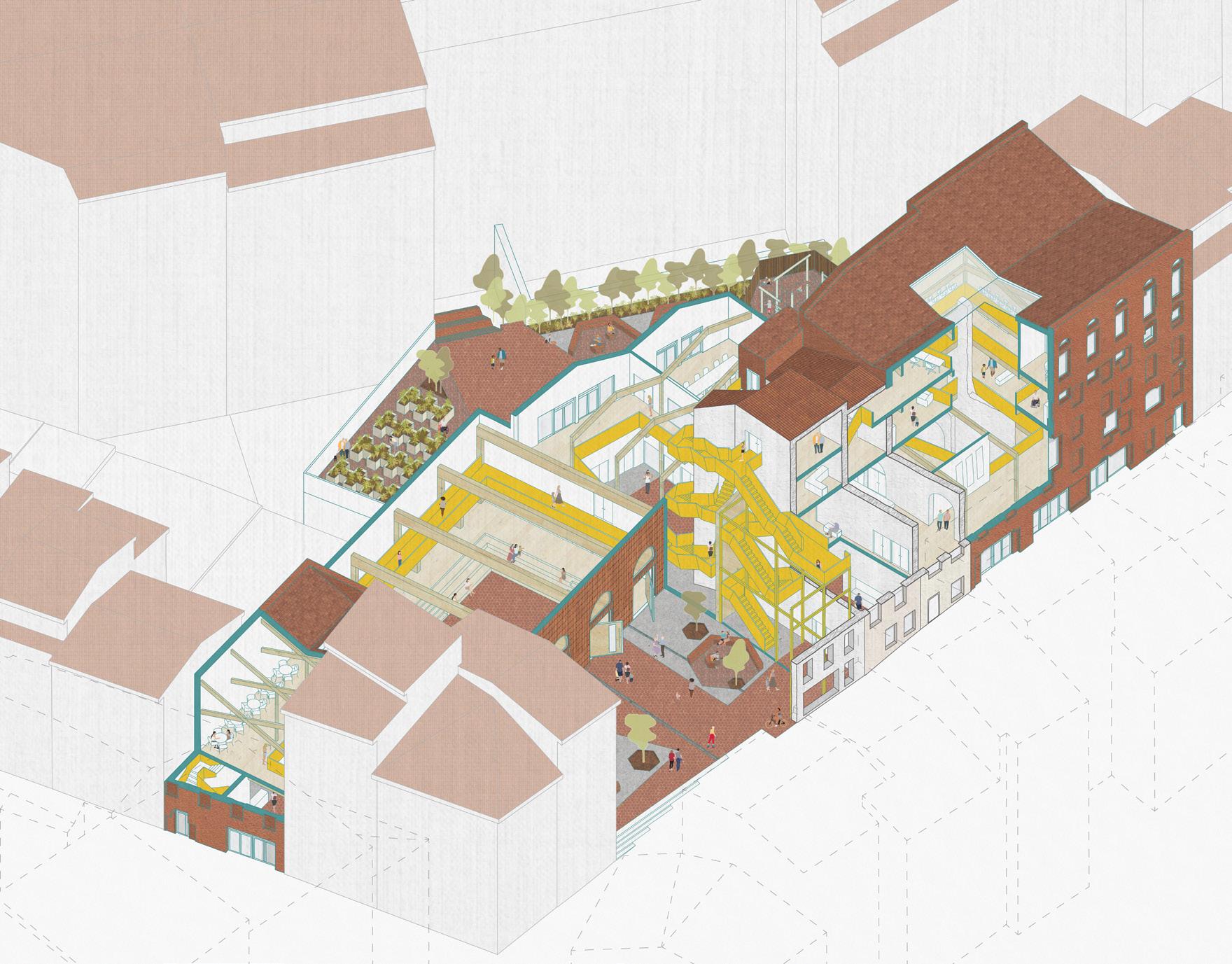

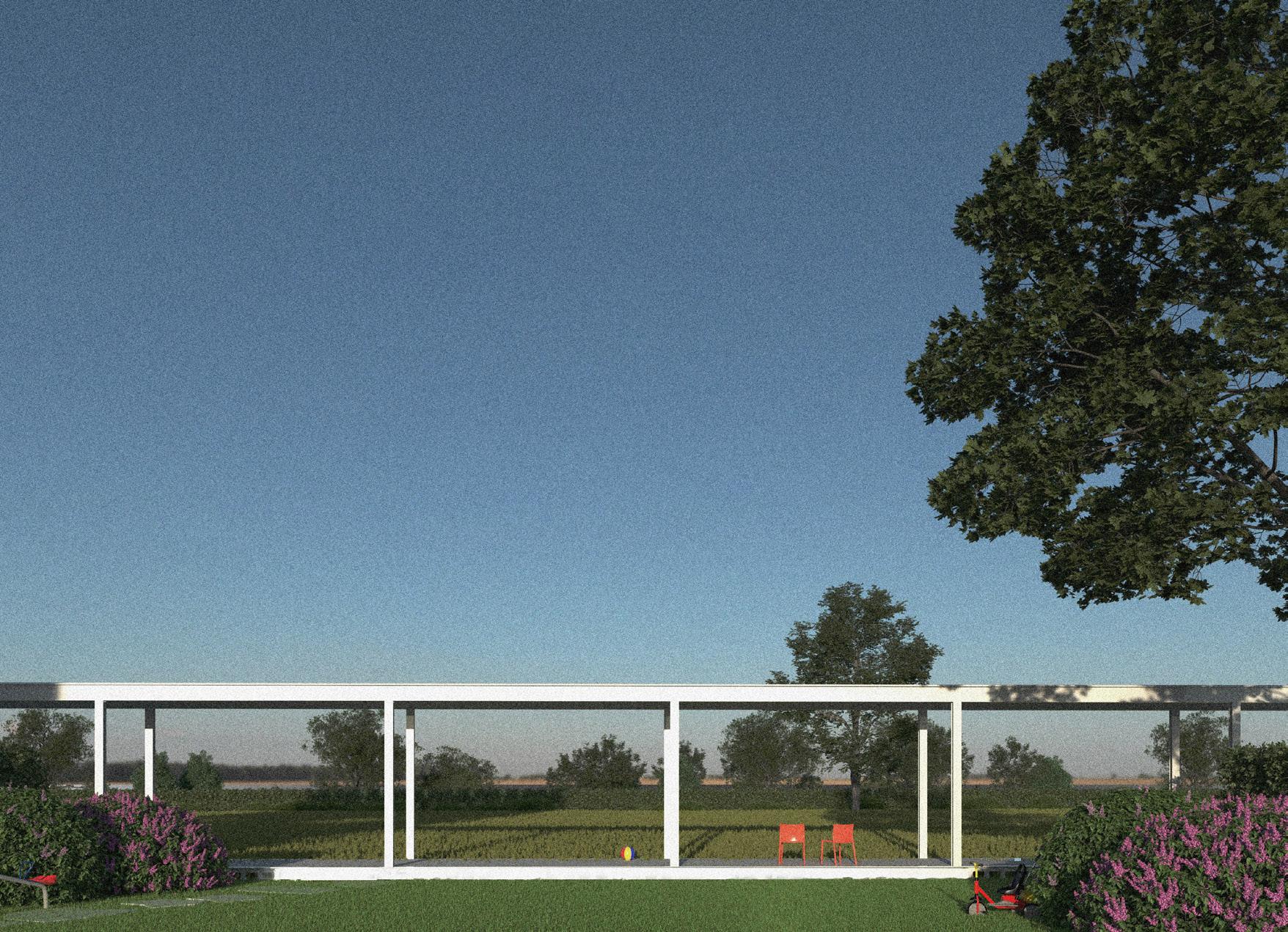

For the emerging Undergraduate Rural Lab, Stage 2 based ourselves in the town of Forres on the Moray coast, our task was to explore issues of a conviviality and climate change within a rural town. Inspired by the thoughts of philosopher and social critic Ivan Illich, using the idea that architecture can be a tool of conviviality, our projects centred around several themes; sustainable forms of living together, adaptive re-use, use of materials, architectural design and the climate crisis.

In Semester 1 we focused on housing. We used the typology of row-housing to explore how densification could be used to create convivial streets.

Studying16 contemporary housing designs by the likes of Mies, Peter Barber, Dorte Mandrup and Aravenna, our students worked in pairs to discover and exchange architectural information on two different schemes from the list, these existing designs were then developed through a series of spatial and programmatic adaptations. A three day convivial study trip to Inverness, Forres and Findhorn allowed us to gather information for a final, site based iteration of housing proposals, located on two existing carpark sites in the centre of Forres.

The trip also enabled us to meet our ‘clients’ at Orchard Road Studios and investigate our fourth and final project of the year in Semester 2. In this project students took an array of very ordinary existing buildings and were asked to carefully knit these together to form an arts based convivial building for Forres. Reducing the impact on carbon emissions and energy conservation were at the forefront of design ideas.

We mustn’t forget our foray into issues of design and the circular economy. Inspired by Thomas Thwaites ‘Toaster Project’ we collaborated with year 2 students of GSA’s Product Design engineering course, to source, deconstruct and forensically analyse components and materials of old IKEA furniture, from which a new product was designed, priced and marketed.

For this project, we took an existing precedent of row housing and created multiple iterations for a defined group of inhabitants.

My precedent was Alvaro Siza’s contribution to social housing, SAAL Bouça, and I chose to design for a multigenerational family. Multigenerational housing challenges the preconceptions of housing in the Western World. I believe our individualistic societies would gain a lot from a closer-knit community. That could mean living in a house with your immediate family or even sharing one with a chosen family, but humans thrive in community, and weaving that back into how we design could be a way to healthier, happier livelihoods.

This was my final iteration; the design motif was inspired by the local architecture in Porto, Portugal and by the designs of Ricardo Boffil, a contemporary of the original architect. The space allows for multiple areas of gathering with varying levels of privacy, and sleeps a family ranging from 4-10 people.

The fundamental characteristic of bricolage is that it is bound by place, using what is at hand. In the case of Robinson, this connection to place and resource is not by choice but out of survival. As a society are we not in a similar position to Robinson? (The world is burning). Could bricolage as a mode of thought help us achieve our climate goals? Evolution does not create perfection but remains open to change. The results are based on limited resources and time,

creating coexistent solutions with other species. It is context sensitive, integrative, valuing dynamism and diversity. It is born out of bricolage.

Through the process of constructing an education space and a studio for 15 artists, our proposal aims to embed underused/forgotten material cultures in Forres via a series of interventions to engage the public with the act of construction. In self build there is a fine line between

the architect absolving themself of responsibility and questioning the hierarchy and agency in the built environment. Is the role of the architect always to produce a finalised design? Our proposal exists on a gradient, as trust is built and skills are learnt, power structures within the design process morph; the architect becomes the facilitator.

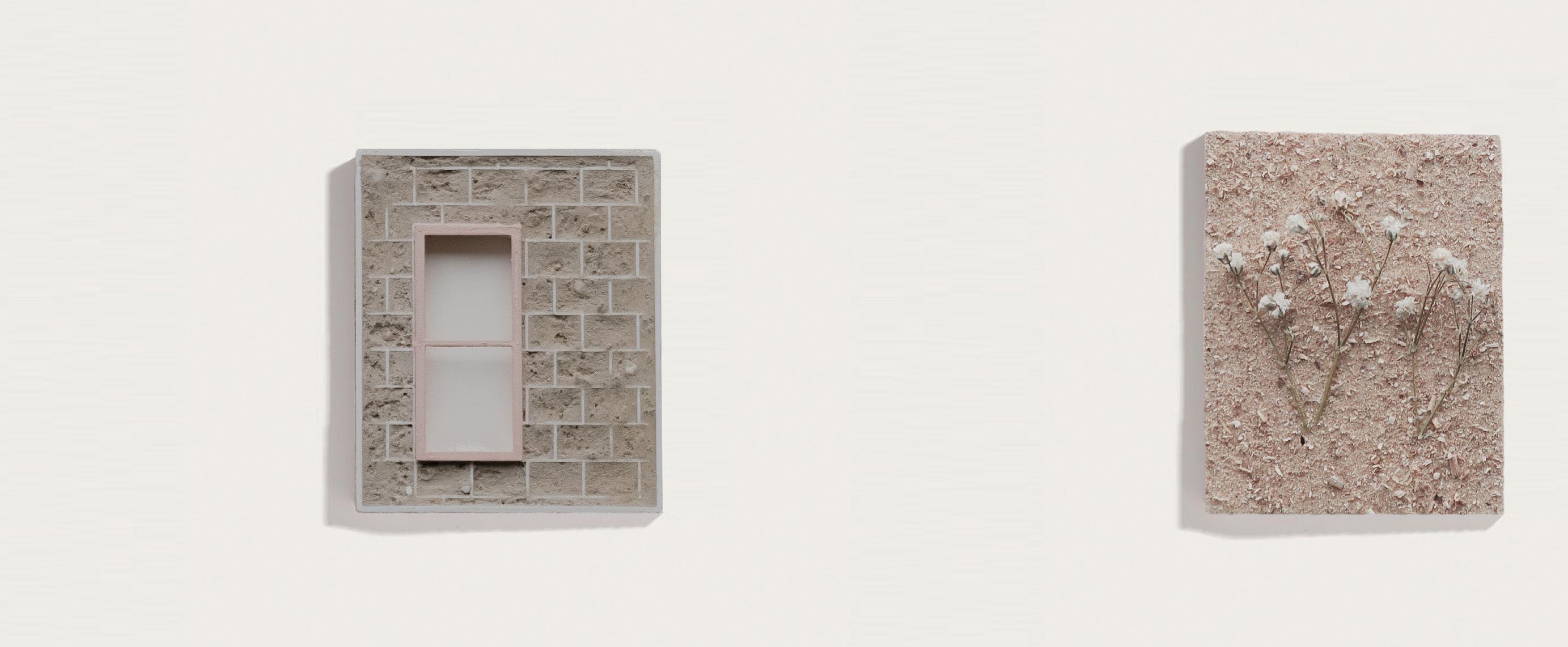

Key

[1] Worm’s Eye View

[2] Heather Study

Orchard Studios is a community art studio that comprises two adapted buildings, further developed to encourage creativity and conversation among artists and visitors. The garden space is of utmost importance to the artists at Orchard Studios, and the new design aims to create a boundaryfree environment that connects the two. The garden is now adorned with local Scottish vegetation, enhancing the appreciation of biodiversity with the landscape.

The artist’s studio prioritizes illumination, with large openings that allow natural light to cascade within, thereby reducing energy consumption and creating a natural atmosphere. Enhanced by using sustainable materials such as stone cladding on both buildings, sourced from local demolition sites, and a thickened envelope for better heat retention.

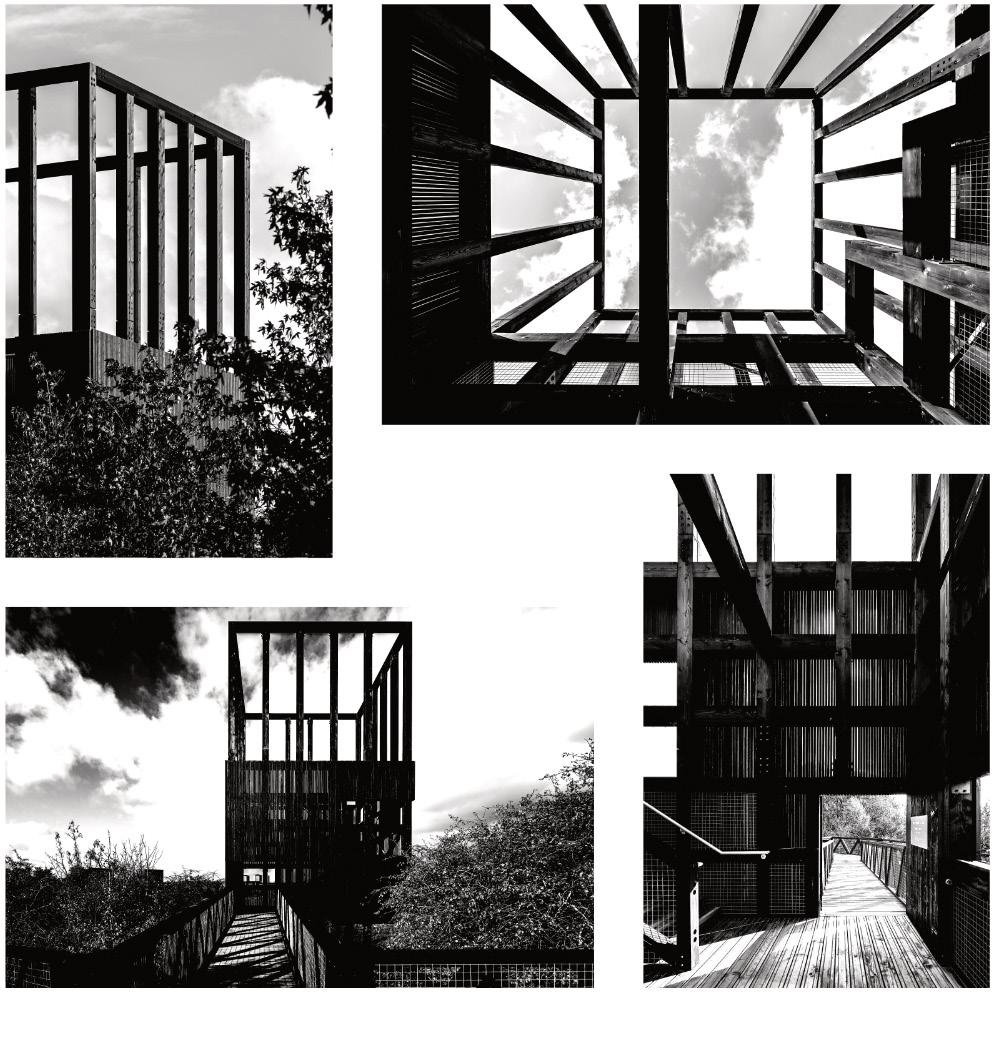

The location features a building for contemporary arts and natural materials, along with a watchtower

that blends into the rural landscape of Forres. The other building is for resident artists, with upgraded amenities to support their creative work. Visitors and resident artists alike can enjoy the garden and connect with nature.

Key

[1] Section Visualisation

[2] Atmospheric Sketch

[3] Orchard Studio Section

[4] Site Visual

The shielin-bough project aimed to take two vernacular shelters from different cultures and use them as a seed to collaboratively design a unique structure that provided shelter and space for learning, storytelling and food on GSA’s Highlands and Islands Campus in Forres. An international collaboration between students from MSA, the Forres Campus and The University of Lapland brought us and a group of students into a series of intense design and sharing sessions in spring of last year which allowed us to learn more about the Scottish Shieling and Finnish Laavu, both of which were somewhat ramshackle shelters for working people in the wilderness, with the shieling for pre-Clearance farmers in the Highlands, and the laavu originally for woodsmen and hunters before latterly becoming a social space for all people in nature.

Following this initial collaborative burst, the design team shrunk to just four in September and continued to work on finalising designs. The project was to be built by students and staff, most of whom would know the site and their own needs far better than we in Glasgow ever could, and so we decided to take a step back from a prescriptive design, and instead specified a loose structural system that could expand or contract, depending on the needs of us building it at the time.

With materials and design more or less ready, we headed to Forres where we met the local students and staff, as well as our Finnish compatriots, and began an intensive building and learning process over a week, where we socialised and learned from each other, visited the local material suppliers we were using, and most importantly built the structure, nearly to completion. A second visit by us from MSA in February helped get the project over the line into completion.

The project involved a great deal of listening; to those from separate and valuable cultures, to those who will use the space, and to those who have expertise in building and construction at this small, human scale. Alongside the practical and

organisational skills involved in acting as organisers and builders, this perhaps was one of the most important things learned in this process, that listening to those who will use your spaces will allow for a unique and fascinating design process. Working collaboratively, loosely and in constant communication with stakeholders is, for now, relatively unique, but creates spaces that are worthwhile, and experiences that are even more so.

Images: Chi-Kwan Kip, Stage 2

Stage Leader

Luca Brunelli

Co-Pilot

Neil Mochrie

Studio Tutors

Ian Alexander

Isabel Garriga

Henry McKeown

Adrian Stewart

As part of the MSA BArch Rural Lab, Stage 3 sets the inquiry in Lochaber and Fort William, inviting students to explore how architecture can serve as a critical tool for reimagining the relationships between local people, tourists, other species, and the landscape that supports them. We adopt the broad conceptual framework of the ‘critical zone,’ as articulated in ecological, social, and political terms by Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel. Beyond merely describing a territory, the ‘critical zone’ has the power to question and prompt a reassessment of our interdependencies with both ‘the world we live in’ and ‘the world we live of,’ the places we inhabit, and the geographic locations from which we extract the resources that sustain our lifestyles. While the scale of these interconnections is planetary, the use of the term ‘zone’ conveys its fragmentary, patchy, and discontinuous condition.

We acknowledge the limitations of architecture and individual buildings to provide radical solutions at the scale of the ecological crisis, however we believe in architecture’s potential to engage with the specific and the fragmentary—the critical zone—and to host human

activities that generate meaningful places. We challenge students to explore how architecture can critically engage with the interdependencies of the critical zone at three levels: spatially, by providing a ‘platform’—a space (a range of spaces organized in buildings)—for observing, learning, and reflecting upon them; materially, by researching and exploring how the sourcing and assembling of materials that form buildings can become a manifestation of their emerging critical position on this issue; and symbolically, by examining how architecture can also express and manifest a critical appraisal of designing in and with the critical zone. This is evidenced through two design projects set in two significantly different contexts: Fort William town centre in semester 1 and the wider Lochaber critical zone in semester 2.

This project is titled ‘Recovering a lost identity’ and has culminated in producing a memorial for Colonialism, in particular looking at Scotland’s involvement in the British Raj. The memorial in its conception began by looking at the vernacular architecture of Assam where many Scottish went over to start and participate in creating tea plantations.

Key

[1] Construction Detail

[2] Plantation and Site Contour Map

[3] Section

The structure begins taking the form of a bamboo house in Assam but then slowly as you move through, down the structure it begins to fragment and fracture creating moments. These moments frame views of the landscape, allowing the viewer to see through the structure as they move down. Once nearing the end of the structure it is seen in a state

of disorder, it no longer appears to be traditional but retains a memory of what once was. At the end the viewer is engaging with the landscape in its entirety and is surrounded by the remaining fragments of the structure, at this point it is but a mere memory.

Project 2 had us design an observatory in the Lochaber area of the Scottish highlands. I have chosen the Knoydart Peninsula for this project and would go on to design a sensory bothy. In this harsh peninsula off the west coast of Scotland, there is a privately owned piece of land, 17,000 acres in size, dedicated to living remotely, in touch with the environment and wildlife. The isolated off-grid living forces the small population of 111 residents to work with each other and the environment in order to live in the land in which they sit.

“In a world of scarcity, interconnection and mutual aid become critical for survival.”

This is becoming more important as the world deals with the effects of overconsumption and climate change. There is much to learn from the sustainable living methods which the people of Knoydart have adopted.

The observatory will be a sensory bothy focusing on individual views of Knoydart, those being the town of Inverie, the distant islands and waterways,

the Munros of the valley, and the peatlands. The form of the building is based on the views; each tapered viewing space looks at one aspect of Knoydart. These viewing spaces are bare rooms with the sole focus on the picture windows. The bothy offers a sheltered space to use your sight to view the good work of ecoliving. The journey to the observatory is as important as the bothy itself.

Key

[1] Picture Windows of Panorama Views

[2] Interior Render

[3] Isometric

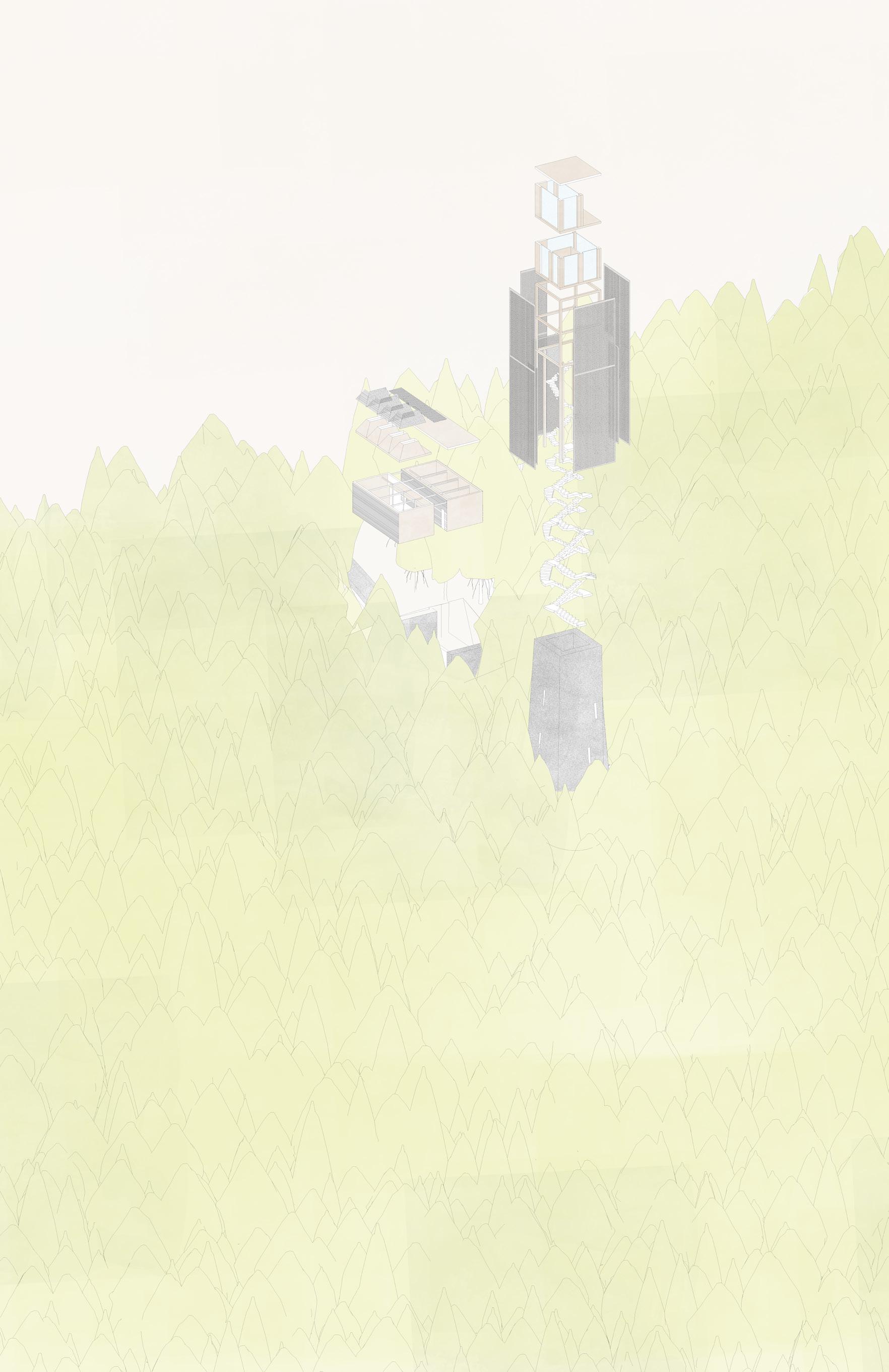

An observatory on someone’s ‘self’, hovering 30m above ground in a remote location of Loch Treig, simulating a stylite experience. Designed to be a thoughtful experience from the first steps to the top of the tower. Where one can stay as long as needed, away from the material world and the word’s temptations, reflect on themselves and a space for contemplation. Where success on the outside begins on the inside. Suspended on a 20m high stone base, that blends in with its environment and then followed by a 10m core wrapped in aluminium mesh, reflecting, and disappearing

with the weather conditions. Complimented and tucked away within the woodlands, by a supporting building to its east, that can accommodate 4 more people that will support the person in the stylite tower, same as a real stylite monk would, that would then take turns on the stylite experience to reflect on themselves and contemplate.

Key

[1] Site Section

[2] Perspective Section

[3] External Render

[4] Exploded Axonometric

The concept focuses upon immersing the visitor emotionally into the environment. The interconnective catalyst is ‘water’, a physical cleansing mechanism provoking an aesthetic engagement with the beauty of the awe inspiring surrounding landscape, promoting personal mental well-being. By instigating personal reflections via the pool and sauna, the aim is to induce behavioural changes, fostering conservatism and a love for the landscape. The pavilion hosts a personal instrumental value, a spiritual encounter, a provision of shelter. Water nurtures an observatory response to go beyond the self.

In this project, I looked at the wider context of Lochaber to gain understanding of the wider rural context and experience of living in this part of Scotland. The Knoydart Peninsula is an area of land that has been bought by the Knoydart foundation and works on the principle that the local community has full control and responsibility over this area. A key part of this small community is the Knoydart Forest Trust, who have planted over 600,000 trees to help boost biodiversity in this landscape. The impact of deforestation in Scotland has

damaged our ecosystems more than most realise, this is because the highlands are now primarily covered in acidic grassland, which is due to poor soil structure (nutrient poor soil that vegetation struggles to survive in). The KFT face two main issues, not having a place to stay when they are planting in remote locations and the soil conditions. This structure provides not only a hub for the people planting trees; it is also made out of mycelium which would help rewild the soil during planting as the mycorrhizal network (a hidden network of

mycelium) is essential for a successful forest as it helps the equal transportation of nutrients between floras. Finally, this structure is semi-permanent so after the forest is planted, any non-biodegradable materials will be removed from the site and the mycelium brick hut will be reclaimed by the forest.

Key

[1] Entrance View

[2] Decay Render

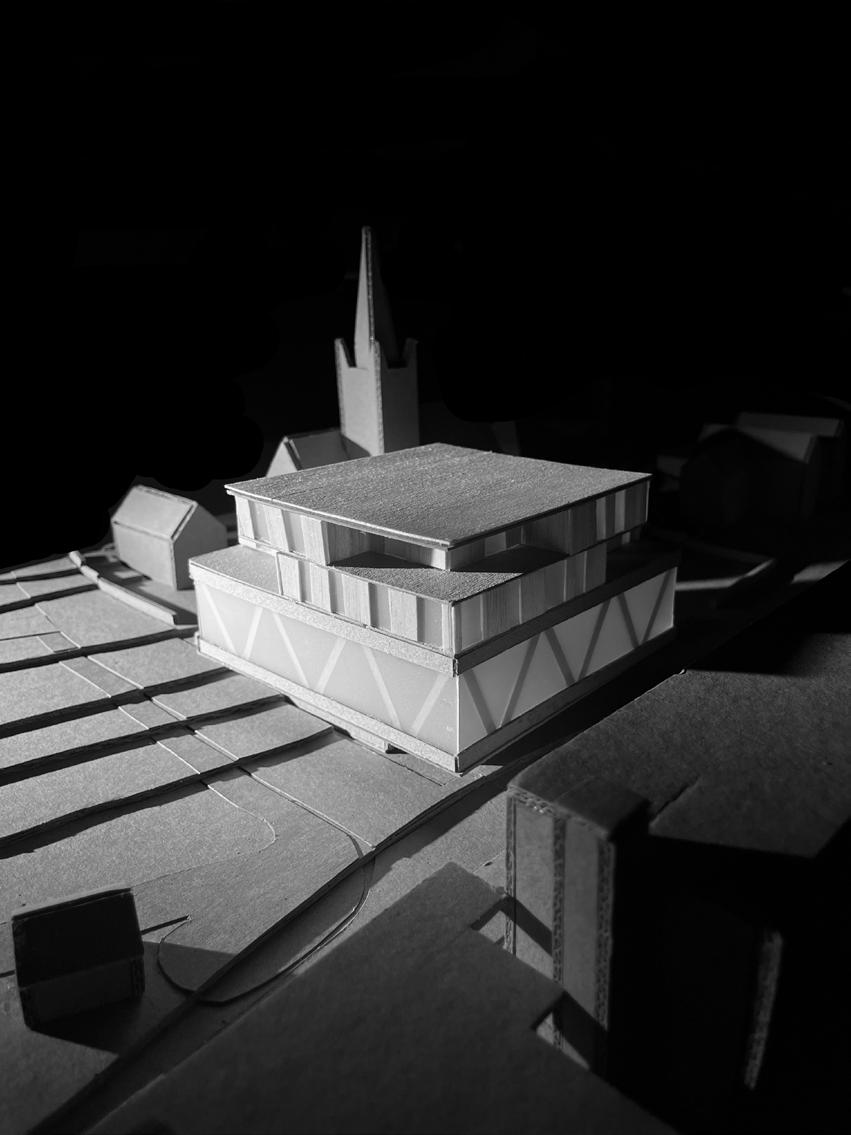

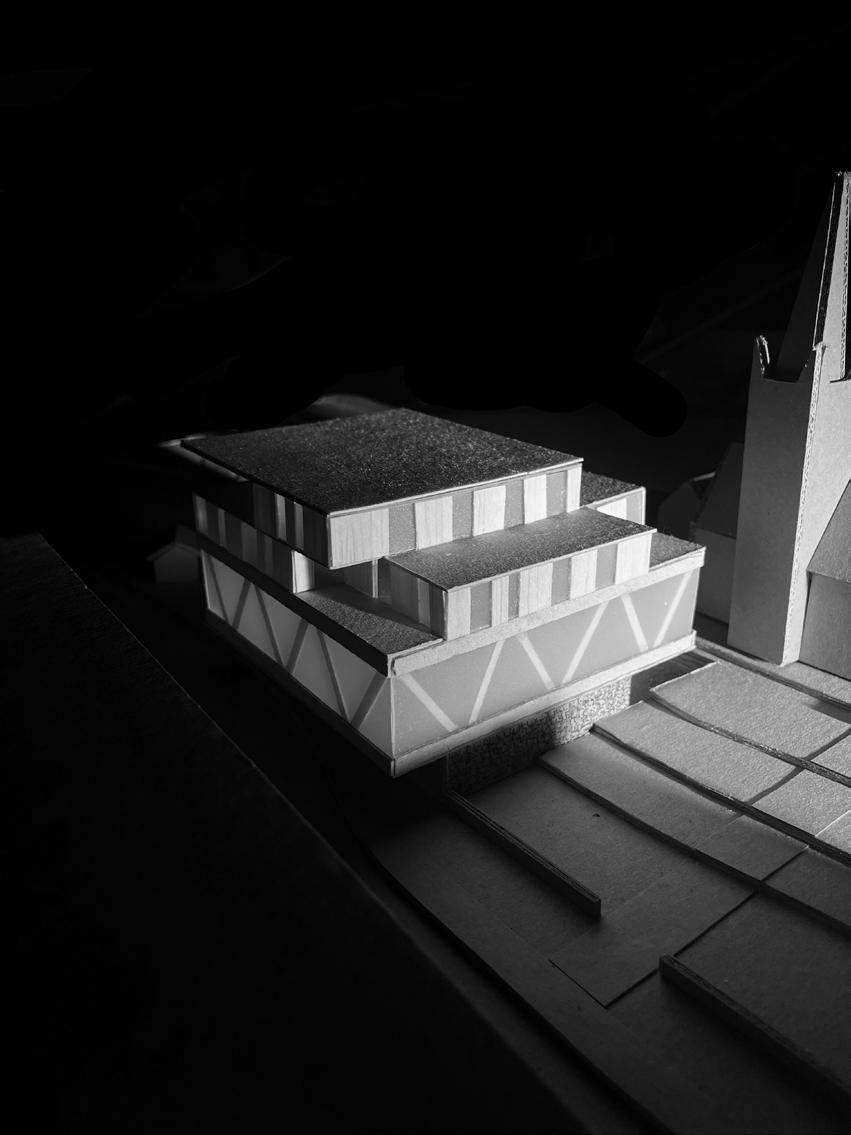

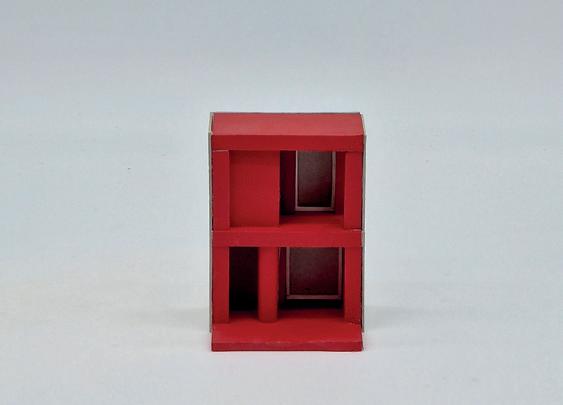

The proposed lifelong crafts learning retreat in Fort William encourages its inhabitants and tourists to engage with the craftsmanship of stone carving in a collaborative manner. It cultivates a sense of community through collective accommodation schedules for short or long-term stays. It also encourages visitors to engage with the local community, socialising the tourism. The design corresponds to its surroundings by creating a walkable space and highlighting outdoor-indoor relations through multiple balconies and outside

exhibitions. The heart of the retreat -the studio- is located on a cantilevered first floor with a glass facade, blurring the boundary between the inside/outside and public/private. The concrete structure on the lower floors creates a dialogue with the stone curated in studios, emphasising its qualities - the rawness, heaviness, and elegance. Its open layout allows easy rescheduling of the internal space, enabling adaptive reuse. The reusable timber structure on the upper floors enhances the design’s sustainability value, boosting

residents’ good health and well-being. The timber used in the structure is sourced from a local company - BSW Timberyard, which boosts the local economy. The retreat is a safe space promoting equality and quality education in the craft, providing new workspaces and accommodations in the town.

Key

[1] Site Sketch

[2] Location Plan

[3] Model

MASS is the Mackintosh Architecture Student Society, an organisation run by the students of the school. The society aims to be the catalyst and backdrop of the incredible studio culture the Mac is renowned for. Having now fully recovered from Covid, and the studio back up and running to its fullest, we’ve been eager to re-instate, re-vive and re-establish the studio culture. Mainly focusing this year of different social events to encourage the inter-mingling of all stages, creating new bonds that are then translated in studio, strengthening our community and learn from each other, because let be honest, if there’s a

command on a software you don’t know, somebody else surely has that sorted!

One thing we’ve been particularly proud of is bringing the Mass Bar back up and running (most of the time). But most importantly bringing back the espresso machine that seemed to be broken for years now! Raising money through the Mass Bar to be able to organise bigger events, allowing for cross GSA students to join in as well, broadening our horizons outside architecture and interacting with the rest of the creative world of the school.

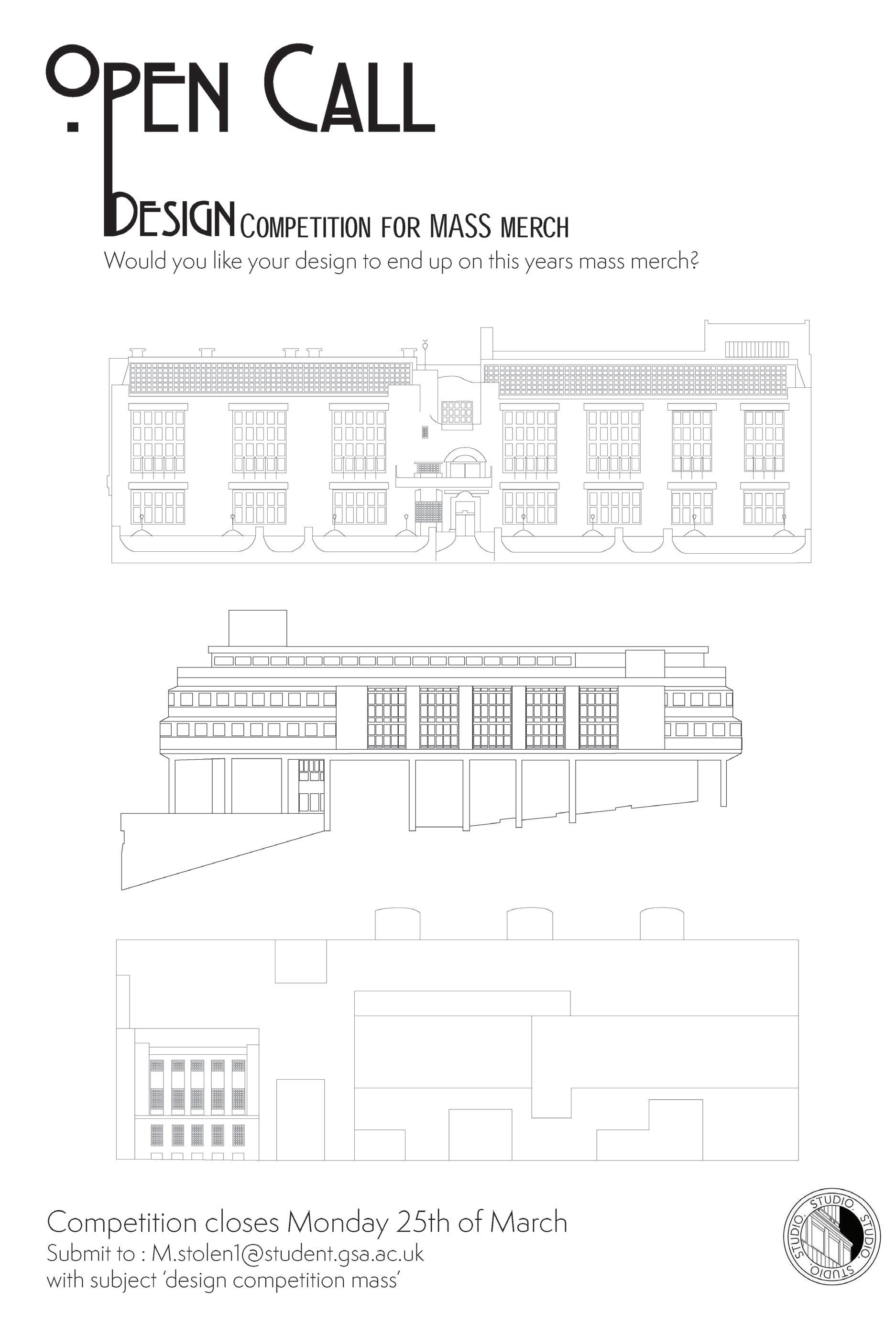

In response to the evolving landscape of architectural education and the opportunities presented by the adjustment in studio spaces at the Mackintosh School of Architecture, we introduced the 1:5 Chair Marquette Competition and a fully funded 1:1 chair live build.

This initiative is conceived not only as a creative endeavour but as a catalyst for revitalizing studio culture, especially in the wake of the disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Acknowledging the MASS coffee bar as an area that students and staff use to socialise. The competition required students and staff to collaborate in teams and the winning designs from the Chair Marquette Competition will be translated into full-scale, full funded, functional chairs through a Live Build collaboration with the Technical department during the upcoming summer. These 1:1 chairs will be situated on the MASS coffee bar.

Sustainable Material Sourcing through Recycling and Up-cycling.

The Chair Marquette Competition and final chair build aims to promote collaboration, sustainability, and thoughtful design principles among students and staff at the Mackintosh School of Architecture and GSA. By challenging participants to create studio-inspired chair marquette using recycled and up-cycled materials, the competition encourages resourcefulness, eco-conscious practices, and reflection on how design impacts studio spaces and users.

Affric Andrew Townend BA Fine Art - Photography Practice

Leonard Yihao Li Master of Letters in Fine Art Practice

Margaret Gray Master of Letters in Art Writing Anthony Di Gaetano Bachelor of Architecture

Tomasz Sawczuk Bachelor of Architecture

Creative Insights: Camillo Feuchter from (@a_chair_with_ no_name), a Dundee-based maker and spatial designer, shares his process of crafting stunning chairs from up-cycled materials at the MASS bar.

Student Showcase: Diverse 1:5 marquette chairs crafted by students from various departments of GSA on display at the MASS bar.

Exploring Materials: Winners of the Chairs for MASSes competition visit Glasgow Wood to select materials for their innovative designs. Glasgow Wood are a charity and social enterprise ensuring that as much timber as possible is reused before being down-cycled into kindling or sending it to landfill. By getting as much of this reclaimed timber as possible back into our community for DIY or garden projects.

In Conversation With...

A grassroots organisation of architectural workers and students that are united in the campaign to end the exploitative methods of practice that have come to define the world of architecture.

“Longer

tables, not taller fences”

CE: Charlie Edmonds

PM: Priti Dipak Mohandas

MM49:

Can you please introduce yourselves and tell us a bit about why you started Future Architects Front?

CE:

I’m Charlie and I’m currently a person with a lot of hats, as most overworked millennials are. The key ones are a CoLead in a group called Civic Square which is an organisation working towards built environment transition in Birmingham and I also teach at LSA in the Critical Practice module. We started FAF in the beginning of 2021 when Priti and I had both recently finished our Masters in Cambridge. Essentially, we wanted to check whether we were seeing the same things that everyone else was seeing. We were increasingly frustrated with how far practice deviates from how you’re taught that architecture is something that is rooted in social and ecological value and then you move into practice and it’s purely coordinated according to capital, land value, and these types of things. It was originally a way of voicing, not only our frustration, but a collective generational frustration with the way that architecture was practised currently, particularly regarding the conditions of younger people in the profession. FAF was originally supposed to just be a vehicle for an open letter that we wrote to the Royal Institute of British Architects but has snowballed to such an extent that it has carried on, through intrinsic momentum.

PM:

I’m Priti, I’m now doing my PhD in Urban Geography and I specialise in looking at rehousing programmes for people that live in informal settlements or live on the streets, particularly in South Africa. A lot of what I look at is also gender and I’m now looking at masculinity, violence and housing and how those things are connected. Overarching all of that, I look at politics, state politics and the idea of government, responsibility and improvement, how that translates down into the home and how the home is representative of big national politics. Social justice has always been at the core of my work and Charlie’s work. We have both always grappled with theory, practice, activism, politics and how to bring all those things together. Instead of going to practice for the placement,

we went off and did field work. Charlie worked in a school and I worked at the frontlines of a grassroots NGO and we felt like we had purpose. We were also doing our thesis and doing all this theory stuff and it was all connecting with design. And then Charlie and I were just constantly going to the pub saying, “What the fuck, we have to end all of this and go sit in an office and do a 9 to 5 and not get paid for all the hours that we’re working?”. That isn’t okay! It’s repeated. It’s cyclical and it’s generational. We didn’t want to do it, we refused to do it. But there was also this fear of being political amongst our colleagues; as if it’s okay to do it within the confines of academia but the moment you go into practice, you’re a little soldier in a big army and you can’t do that anymore. There was an article in the AJ by FAME (Female Architects of Minority Ethnic) about the chances of a woman getting into the senior ranks of an architecture firm, and then you look at the racial statistics behind that and I was like, “What is the point of me even being here? I can’t make any systematic change.”

CE:

“Our deviation from the traditional route to qualification is not because we couldn’t get to the Part Three if we wanted, it’s because we thought we could actually contribute so much more to the built environment through avenues outside of architecture.”

MM49:

It’s nice to get to know the roots of FAF a bit better. You discussed the open letter to the senior management of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) in 2021. We were interested to know how that came about, what that looked like and its response?

CE:

We decided the RIBA made sense as a first target of the organisation. At the time FAF wasn’t anything, it was just an Instagram page with a few hundred followers of people who had responded to some questionnaires that we’d put out and shared their frustrations with practice at the moment. So we knew that for us to try and intervene effectively in these wider systemic contexts, we would need to find a leverage point. RIBA was a great leverage point because not only are they a really big, well known, globally recognised architecture institution, they also have a fair amount of autonomy in the sense that they have their own council and board, they are a charity, they can set their own code of practice. Whereas sometimes people ask, why didn’t we initially start talking to the ARB (Architects Registration Board)? But the ARB are directed according to policy and government departments so the ability to leverage and influence their behaviour is far less viable than a more independent organisation like RIBA. Around half of all architectural practices are RIBA chartered which means that if you can introduce something into the RIBA Code of Practice, like a ban on unpaid overtime, you effectively change the landscape of the profession dramatically just with one update to a code of conduct.

If you look at the RIBA election turnouts, it pretty much never goes above 15% of membership voting in any election. So it’s also an organisation that is really steered by a small minority of figures who understand that they can utilise it for their own interests. At the time, there wasn’t really any organised group trying to push back against that. If you look at the history of RIBA Presidents prior to Muyiwa Oki, they’ve all been 50+ years old, generally white men, who own their own practices. Muyiwa is the first person who is actually a worker who’s in that position. Essentially, we’re looking at the influence that the

RIBA could have when compared to the contemporary intentional uselessness of the Institute. It’s intentionally not trying to do anything bold or radical. The open letter was based on a survey that we had put out, which asked people to share the conditions they were working under. Generally, things like if they were working unpaid overtime, if they could live comfortably on their salary, and one question said “Do you feel supported by RIBA” and around 95% of people said no. That provided the quantitative basis to the letter which showed that things are bad, particularly for younger people in the profession. We also asked people in this form to share experiences in a long form written capacity and through reading all of those experiences, we boiled down our demands. The demands were things like to ban unpaid overtime, to introduce more inclusive governance to RIBA and to have greater transparency in spending. It was incredibly well received, even though we were very unknown at this point. We got over 1800 signatures in a couple of weeks.

RIBA did a response to it, they met with us and they said they were going to consult on actioning all of the demands. Perhaps unsurprisingly, nothing ended up coming of that, even though it was posted on their website that they were going to do all of these things. It’s still up there, you can still go and look at it and they say, “We had the meeting and we’re going to do all this stuff” and nothing ever came of it. So we then asked ourselves, if the people in the RIBA aren’t going to do anything in the face of a huge democratic demand to do something, then why don’t we just take advantage of the low voter turnout and elect some people ourselves, who will do something?

PM:

All of this came from a place of curiosity on our part, and the timing was perfect. It was COVID and we were all at home. Charlie and I were talking about how we knew these patterns of exploitation were embedded within our profession, but we needed to find a way to bring all those experiences together and to validate our own feelings that we had on the issue. And that’s really what the letter did. Our entire friendship at the time was based on sending these stupid memes that were very political. When

Charlie started posting these on the FAF Instagram page, it really started tumbling and people started catching on and the numbers just increased so rapidly and vastly. Then we started interacting with other organisations like SAW (Section of Architectural Workers) and unionising started to become a part of it. It all really did come from a place of curiosity and the pace and intensity of it shows how universal a lot of these experiences are. The thing got legs, and ran!

MM49:

The meme format plays a big part of your online presence and is a much more visual way to engage with people online. How has this light-hearted and humorous approach raised engagement with the issues you’re tackling and how might you see its potential in acting as a democratising tool?

CE:

It’s definitely a multifaceted thing because the memes serve several different purposes. One is definitely democratising the information and making the conversations we’re having, and the organising we’re doing, far more accessible. One of my favourite ones we’ve ever made is an old man handing out machine guns to little animals, which represent how we try to build class consciousness through our work with young architects - who are then able to ‘fire’ and fight back through joining a union. [1]

Essentially, that’s a theory to practice pipeline that I’m sure if you wanted to you could make that a really elaborate essay about class consciousness and political agency. But you could also just do this and get the same point across. A lot of great critique takes the form of writing and essays, but if you solely exist in that long form, critical writing space, I think you miss a really huge opportunity to make your point and connect with more people. There’s another side to it as well which is the ad hoc DIY nature of organising like this, because the whole FAF page is almost like a throwback to old political zines. The whole point of an old 60s, 70s zine is that they’re cheaply made, they’re printed as low fi and as easy and quickly as possible. You’re mainly interested in getting the message out and you’re not fixating too much on how finessed or glossy the actual product itself is. A lot of the visuals and aesthetics and memes of FAF have come down to necessity, it has to be strategically as low energy but as high impact output as possible. The meme is the best encapsulation of that because it can take five minutes to make but you can have a huge impact. I think the funniest example of that for me, is this one [2], which was the lowest effort. After posting this, SAW, the architecture union, told me that in the wake of this, about 50 people joined the union. That is the perfect example of low energy input, high energy output.

“I think a ridiculous image highlights the ridiculousness of the situation and the stupidity of it.”

PM:

An important thing that maybe we don’t realise is that we’re making the intangible tangible, through an image. I think that’s what garnered so much momentum because it was physically there for the first time, it’s not just stuff that we’ve been told all over all these years. The exploitation in architectural practice is like an urban myth so to actually have it visual has been so powerful. I think a ridiculous image highlights the ridiculousness of the situation and the stupidity of it. It’s not difficult. Pay people. We’re going through all this trouble and drama just to get a really simple outcome.

MM49:

Thankfully, the architectural sphere is beginning to generate more discourse around the exploitation of architectural workers, specifically architectural assistants. As a large percentage of our reader base are students, what are the exploitative tactics that young designers and architects should look out for in the workplace?

CE:

The main one is definitely unpaid overtime. There’s an AJ investigation into the conditions of architectural assistants and a lot of the investigation was done in collaboration with us because we drove a significant number of people to fill out the survey. They found that 40% of Part One

architectural assistants are paid less than a real living wage, 88% of Part One and Two architectural assistants say they’re never paid for overtime and 8% of people said they’re working without a contract. And 16% said during COVID they were asked to work while on furlough. We’re in a profession that routinely either breaks or pushes the limits of what is acceptable as employment law in the UK. I think the biggest problem is that you aren’t taught these things in university, even in a Management Practice and Law course. You’re typically taught about the profession from the perspective of a practice owner. You’re not taught what the Working Time Directive is, for example, which sets out the maximum amount of hours that you can be asked to work per week by law. You’re not told about the fact that the vast majority of architecture practices will ask you to opt out of that, so that they can ask you to work more than those hours. You’re not taught that you actually have no obligation to opt out from that and if you say to a practice that’s offering you a job, actually no I’m not going to do that, I’m going to keep my rights as a worker, it is illegal for them to withdraw the job offer. All of these things, which are hugely important, are not taught in architecture school, or at least they weren’t when we went to architecture school.

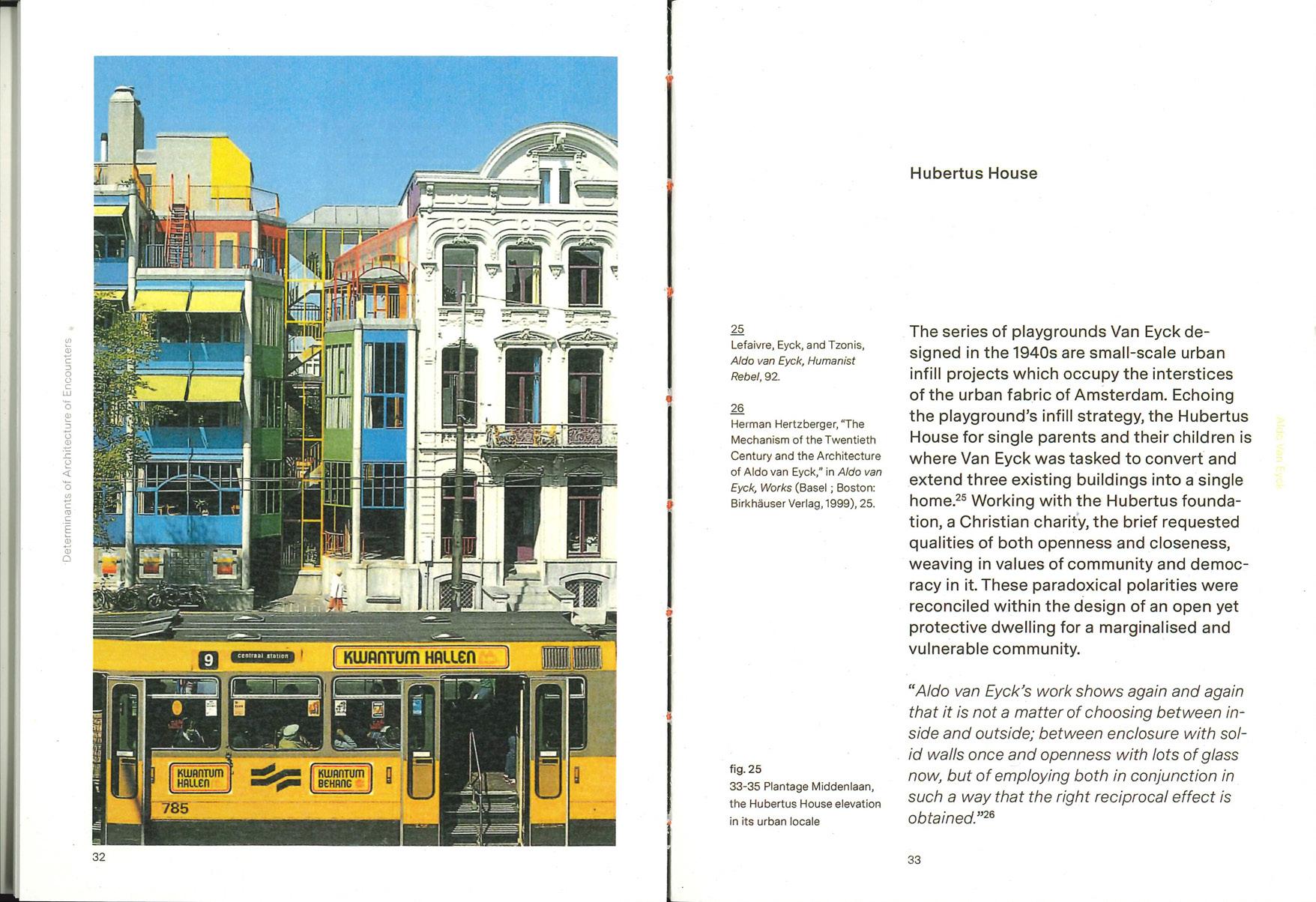

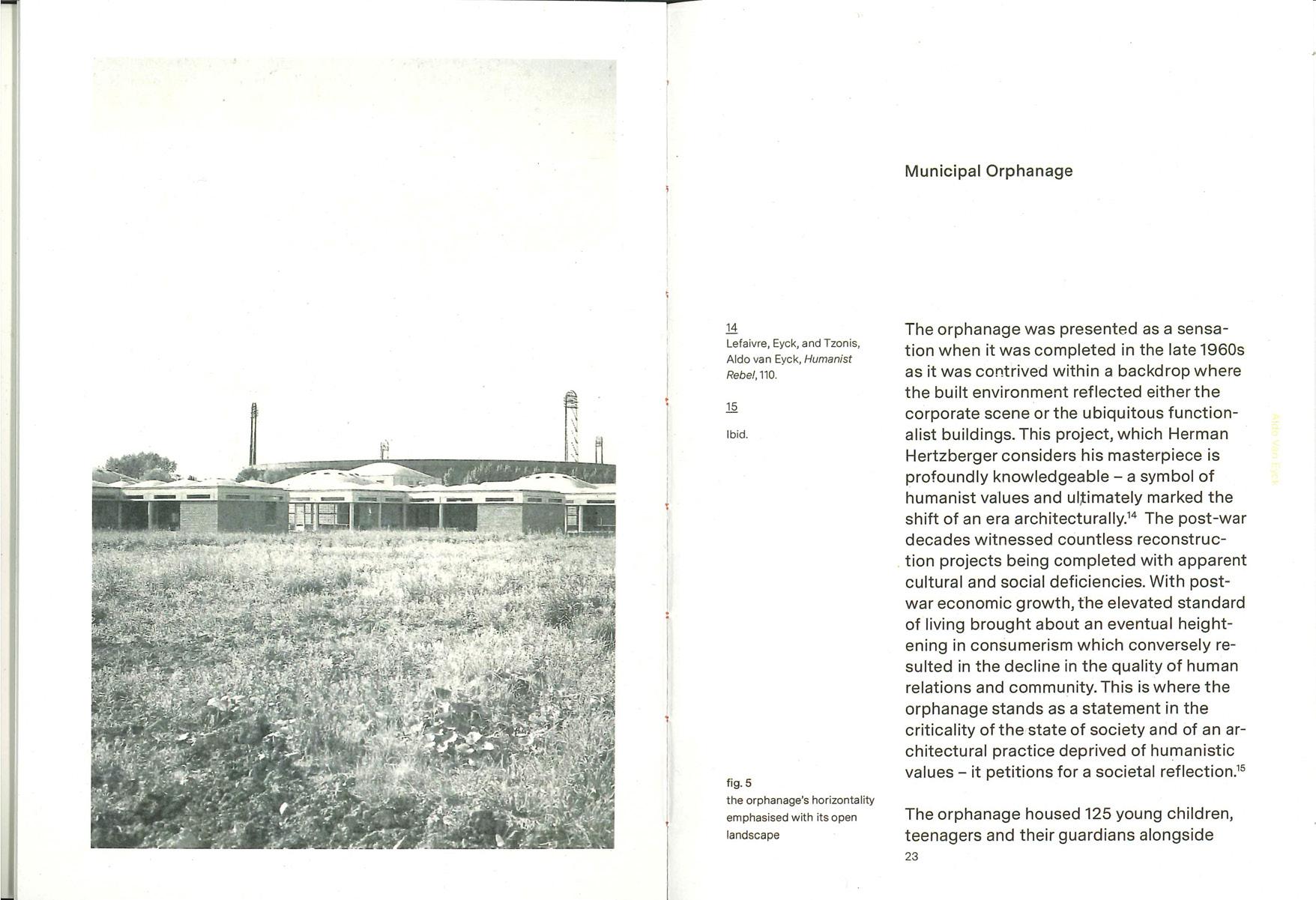

Joining the union is the most important thing that any graduate can do. Not only does it connect you directly to the best source of information for your rights but it also connects you to a group of people who are going to have solidarity with your place in the world as a worker and connect you with a group of people who are going to stand up, not just for themselves but for you as well, and are very much committed to transforming the conditions for architectural workers in the UK. From my point of view, it’s a no-brainer to join the union. There’s no downsides. It’s an amazing group of people and they’re doing incredible, important work. Right now we’re seeing loads of practices go through quite big redundancy processes and a lot of people are panic joining the union because of this, but the frustrating thing is that because of the draconian union rules in the UK, you need to have been in the union for at least two months before they