2022-23

Mitra FAMILY GRANT Recipient

Languages Live On: The Impact of Indigenous Languages on the Development of Modern Spanish in South America

Isha Moorjani

Languages Live On:

The Impact of Indigenous Languages on the Development of Modern Spanish

Isha Moorjani

2023 Mitra Family Scholar

Mentors: Ms. Isabel García, Mrs. Lauri Vaughan

April 12, 2023

Although most people living in Latin America speak Spanish, the language variations are diverse and by no means identical to the language spoken in Spain. Scholars have attributed this diversity to multiple factors, including immigration and the impact of Indigenous languages. Many Indigenous languages that thrived prior to colonization in the early sixteenth century are still spoken today to varying degrees. Their early interaction with the Spanish language also allowed them to influence the Spanish spoken in Latin America through lexical, phonetic, and morphosyntactic means.

Indigenous populations established themselves in the regions that currently form Chile approximately 10,000 years ago. Specifically, Mapuche peoples include a variety of ethnic groups.1 Varieties of the Mapudungun languages thrived in the regions that now form Chile and parts of Argentina (see fig. 1).2 While Spanish conqueror Pedro de Valdivia attacked the Mapocho Valley in Chile in 1536 and took land previously owned by the Inca Empire, he was unable to seize the Mapuche land across the Bío River.3 The Spanish conquerors, however, eventually forced the Mapuche to move further south.4 The Mapuche successfully retained control of their lands until the 1880s, when their lands became part of Chile, and many were placed in reducciones, or “reductions.”5 Mapuche opposition, however, continued and endured

1 "Chile," in Countries of the World and Their Leaders Yearbook 2021, ed. Karen Ellicott (Farmington Hills, MI: Gale, 2020), 1, Gale in Context: World History.; "Mapuches," in Americas, 2nd ed., ed. Timothy L. Gall and Jeneen Hobby, vol. 2, Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life (Detroit, MI: Gale, 2009), Gale in Context: World History

2 "Mapuches."

3 Martin Haspelmath and Uri Tadmor, eds., Loanwords in the World's Languages: A Comparative Handbook (Berlin, Germany: De Gruyter, 2009), 1044 -45, ProQuest Ebook Central

4 José Ignacio Hualde, Antxon Olarrea, and Erin O'Rourke, eds., The Handbook of Hispanic Linguistics , Blackwell Handbooks in Linguistics Ser. (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2012), 93:78 , ProQuest Ebook Central

5 “Mapuches,” ed. Timothy L. Gall and Jeneen Hobby; Ana Mariella Bacigalupo, "Mapuche," in Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture , 2nd ed., ed. Jay Kinsbruner and Erick D. Langer (Detroit, MI: Charles Scribner's Sons, 2008), 4 , Gale in Context: World History.

during Augusto Pinochet’s regime in the late twentieth century, and advocacy efforts for Mapuche rights continue today.6

Far from Chile in the South Pacific Ocean lies Easter Island, or La Isla de Pascua.

Current findings suggest that the Polynesian Rapa Nui society began around 1200 on Easter

6 “Mapuches,” ed. Timothy L. Gall and Jeneen Hobby.

7 Martin Haspelmath and Uri Tadmor, eds., Loanwords in the World's Languages: A Comparative Handbook , 1038.

Island. The Rapa Nui population experienced a dramatic fall in the late seventeenth century, due to shifts in Easter Island’s environment.8 Dutch traveler Jacob Roggeveen arrived on Easter Island in 1722, initiating interaction with Europeans. The Rapa Nui population continued to fluctuate in the late 1700s before facing another rapid fall in 1862, as many were brought to South America as slaves while disease attacked those back home. Easter Island’s contact with the Spanish language was catalyzed by the island’s annexation by Chile in 1888, by then an independent country.9 Since the Mapudungun language has been in contact with Chilean Spanish over hundreds of years, and the Rapa Nui language has been in contact with Chilean Spanish since Easter Island’s annexation, it is reasonable to suggest that both languages have influenced Spanish in some way. However, the idea of language contact between Indigenous languages and Chilean Spanish has been ignored. Examining the Indigenous language Nahuatl’s influence on Mexican Spanish, a more well-researched case of language contact in South America and identifying parallels between these cases of language contact thus is beneficial.

The Uto-Aztecan Nahuatl language influenced the Spanish spoken in the regions that now form Mexico, specifically around the Basin of Mexico and central Mesoamerica. (see fig. 2)

The Nahuas, an Indigenous population, spoke primarily Nahuatl, and many were able to maintain a sense of their cultural identity through altepetls, or small political entities, despite Hernán Cortés’ defeat of the Aztec Empire in 1521. 10 Nahuatl was also widely used as a lingua franca to

8 "Rapa Nui," in Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life , 3rd ed. (Farmington Hills, MI: Gale, 2017), 4 , Gale in Context: World History

9 "Rapa Nui," 4.

10 Robert Haskett, "Nahuas," in Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture , 2nd ed., ed. Jay Kinsbruner and Erick D. Langer (Detroit, MI: Charles Scribner's Sons, 2008), 4 , Gale in Context: World History .; Justyna Olko, "Language Encounters: Toward a Better Comprehension of Contact -Induced Lexical Change in Colonial Nahuatl," Politeja: Europe-Latin America Cultural Encounters, no. 38 (2015): 36, JSTOR.

enable translation between various languages before and after Europeans landed in South America.11 Scholars currently have access to a wide variety of Nahuatl documents, as the Nahuas not only used their glyphic and partially syllabic scripts, but they also learned the Latin alphabet from Spanish missionaries who achieved fluency in Nahuatl. This abundance of writing allows for deeper exploration into linguistic contact with the Spanish language. 12

11 Ingrid Petkova, "La Presencia de los Nahuatlismos en el Español de México desde un Enfoque Diacrónico," Acta Hispanica 22 (2017): 46.; Olko, "Language Encounters," 36 , ProQuest.

12 Olko, 36.; Robert Haskett, "Nahuatl," in Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture , 2nd ed., ed. Jay Kinsbruner and Erick D. Langer (New York City, NY: Charles Scribner's Sons, 2008), 4, Gale in Context: World History.

13 Data from University of California, San Diego, "Map of Ancient Mexico," map, JSTOR.

Nahuatl-Spanish interaction shares many parallels with Rapa Nui-Spanish and Mapudungun-Spanish interaction, suggesting that Chilean Indigenous languages and their impact on Spanish require further study. While much of past research suggests the absence of linguistic influence from Chile’s Indigenous populations on modern Chilean Spanish, diachronic contact linguistics mechanisms, as seen through the influence of Nahuatl on Mexican Spanish, affirm the true extent of Mapudungun and Rapa Nui influence on Chilean Spanish.

The Development of the Spanish Language in Latin America

Before exploring how Indigenous languages have interacted with Spanish in Latin America over centuries, it is vital to understand the Spanish language’s arrival and development in Latin America. Koineization, a process that occurs when people who speak the same language with varying dialects or speaking styles come together, creates a new variation of the language or dialect.14 As Spain’s various regions possess varying speech styles, koineization can explain how Spanish spread in Latin America from individuals who emigrated from Spain. However, scholars have disagreed about the pattern of koineization that occurred in Latin America, leading to two main theories: the Andalucista hypothesis and the multiple koines hypothesis.15

Ralph Penny, who advances the Andalucista hypothesis, cites the work of researcher

Peter Boyd-Bowman and argues that despite the variety of Spanish regions represented in those who traveled from Spain to Latin America in the 1500s and 1600s, the Spanish language in Latin America at the time most closely reflected that of the southernmost region of Spain, Andalusia. 16

14 Ralph Penny, "Variation in Spanish America," in Variation and Change in Spanish (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 40-41, ProQuest Ebook Central.

15 Karen Dakin, Claudia Parodi, and Natalie Operstein, eds., Language Contact and Change in Mesoamerica and Beyond, Studies in Language Companion Ser. (Amsterdam, Netherlands: John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2017), 185:158, ProQuest Ebook Central.

16 Penny, "Variation in Spanish America," 141.

Penny explains a variety of reasons that help scholars understand why Andalusian Spanish may have impacted Latin American Spanish more dramatically than other dialects.17 Penny argues that many Andalusians moved to the Caribbean near the end of the fifteenth century. Since the Caribbean served as a stopping point for those making the journey to South America from Spain, the Andalusian variety of Spanish could have traveled to South America with travelers. Additionally, given family power dynamics centuries ago, women spent more time with their children than men. Since, according to Penny, most of the women who moved from Spain to South America within the first century of contact were Andalusian, it is reasonable to assert that many of the children raised by these women also spoke Andalusian Spanish. Lastly, relative to the number of people traveling from other Spanish regions mentioned earlier, there were more Andalusians overall who traveled to South America in the fifteenth century. 18 Penny also describes additional reasons that explain Andalusian Spanish’s impact on L atin American Spanish. For example, those who desired to travel to South America needed to remain near an Andalusian harbor for a time that ranged from a few months to one year, resulting in some degree of language transfer or acclimatization. 19

Andalusian features that transferred into Latin American Spanish include the pronunciation phenomenon of seseo, which is when /s/ and /z/ are both pronounced as /s/, as well as the use of the pronoun ustedes to describe two or more people rather than both the informal pronoun vosotros and the formal ustedes. 20 Thus, given the interaction between Spanish speakers

17 Penny, 142.

18 Penny, 141.

19 Penny, 141-142.

20 Penny, 142-144.

from a variety of Spanish regions and the transfer of largely Andalusian features of the language, koineization serves as a useful lens through which scholars can explore the development of the Spanish language in Latin America.

Dakin, Parodi, and Operstein, however, argue in favor of the “multiple koines” hypothesis. Dakin explains koineization in Latin America through two stages: intragroup accommodation and leveled speech.21 Intragroup accommodation occurred in the 1500s when people arrived from different regions of Spain and were exposed to other Spanish variations. This interaction gradually resulted in leveled speech when Spanish speakers in Latin America largely adopted features of Old Castilian and Andalusian Spanish.22 To support this claim, Dakin studied hispanisms, or Spanish loanwords incorporated into Indigenous languages in Latin America, to demonstrate the variety of Spanish dialects that influenced Latin American Spanish and how the development of various koines ensued because of the interaction between those dialects. For example, the same Spanish loanwords are incorporated into Indigenous languages with different sounds based on the Spanish variation that was in contact with those Indigenous languages. Thus, “the loanwords from Spanish in the Amerindian languages show evidence of contact of Indigenous language speakers with speakers of Andalusian Spanish, Old Castilian Spanish as well as with speakers of the different koines that originated in the New World.” 23 The evidence backing the Andalucista hypothesis, demonstrated by Penny, and the reasoning behind the multiple koines hypothesis, demonstrated by Dakin, highlight the fascinating complexity behind language interaction and the early development of the Spanish language in Latin

21 Dakin, Parodi, and Operstein, Language Contact and Change in Mesoamerica and Beyond, 162.

22 Dakin, Parodi, and Operstein, 162.

23 Dakin, Parodi, and Operstein, 159 -160.

America. Thus, language is constantly changing based on interaction with other languages and dialects. The Nahuatl Language’s

Influence on the Spanish Language in Mexico

Before exploring features of the Nahuatl language that have influenced the Spanish spoken in the regions that now form Mexico, as well as features of Spanish that have entered Nahuatl, it is useful to first explain the superstratum and substratum theory of contact linguistics. When a group of people move from one region to another and their language becomes the primary language of that region, that language becomes the superstratum. 24 The superstratum eventually impacts the language that previously served as the primary language for that region, or the substratum, but the substratum does not completely disappear. 25 According to the concept of “delayed effect contact,” if the superstratum and substratum interact for hundreds of years, the substratum may actually slowly affect the superstratum.26 Using James Lockhart’s detailed steps of language contact between Nahuatl and Spanish, it is clear that this superstratum and substratum theory of contact linguistics effectively describes the interaction between Nahuatl, the substratum, and Spanish, the superstratum.

Olko explains that Lockhart’s theory of language transfer consists of three major stages that cover from Spanish arrival in Latin America to today. Lockhart studied the interaction

24 Raymond Hickey, ed., The Handbook of Language Contact , 2nd ed., Blackwell Handbooks in Linguistics Ser. (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2020), 425 -426, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/harkerebooks/detail.action?docID=6335166.

25 Hickey, 425-426.

26 Hickey, 10.

between Nahuatl and Spanish in the late twentieth century, and his hypothesis of language transfer accounts for neologisms, borrowing, and transfer of phonetic and syntactic features. 27

Phase 1, which covers the period from when the Spanish went to Latin America to the mid-sixteenth century, focuses on the prevalence of neologisms rather than drastic linguistic change in Nahuatl. Evidence suggests that many neologisms, or newly created words, eventually became part of common vocabulary, and soon, these Nahuatl neologisms carried the same significance as Spanish loanwords that entered the Nahuatl language. 28 For instance, the Nahuatl word guajolote became a synonym for the Spanish word pavo, which translates to turkey; the Nahuatl word cuate became a synonym for the Spanish word amigo, or friend; and the Nahuatl word chamaco became a synonym for the Spanish word niño, boy or child.29

Spanning the mid-1500s to 1600s, Phase 2 focuses on the transfer of nouns from Spanish into Nahuatl.30 However, these loanwords did not always transfer exactly as they existed in Spanish. In fact, many were modified to fit within the Nahuatl language. For example, the Spanish word imagen, or image, became magen or maxen in Nahuatl. Additionally, the Spanish word regidor, which means governing or councilor, is lexitol in Nahuatl.31 In some cases, words would transfer from Nahuatl into Spanish. Spanish speakers would adapt the word, and the latest version would return to Nahuatl. This phenomenon is known as backward borrowing. For example, the Nahuatl word for chocolate, xocolatl, entered Spanish as chocolatera, which then

27 Olko, "Language Encounters,” 37.

28 Olko, 37-40.

29 Petkova, "La Presencia de los Nahuatlismos en el Español de México desde un Enfoque Diacrónico," 46.

30 Olko, "Language Encounters,” 38.

31 Olko, 44.

transferred back into Nahuatl. Evidence appears in a Nahuatl document from 1650. 32 The etymology of xocolatl itself, alternatively spelled as chocolātl, is also fascinating. According to Merriam Webster, chocolātl’s source words include chikolli, which means hook and likely describes the tool that the Aztecs utilized to combine water and chocolate, and ātl, which signifies liquid or water.33 Some scholars, however, argue that the root word xocol means bitter, so xocolatl means bitter water, and other scholars argue that the first part of the word is derived from the Yucatec Maya root word chokol, which signifies hot.34 More examples of loanwords from Nahuatl to Spanish include jitomate or tomate for tomato, popote for straw, elote for corn, and chapulín for a locust or grasshopper.35 According to Petkova, evidence of many Nahuatl loanwords can also be found in Hernán Cortés’ letters, or his five relaciones, that he wrote to Spanish king Carlos I in the early sixteenth century. These letters described Cortés’ experiences, and the Nahuatl words he used referred to items common in Nahua society, but not necessarily Spanish society. Examples include acal, cacao, and panicap, which refer to a paddle boat, a cacao bean, and a type of beverage, respectively. 36

Phase 3, which covers the mid-1600s to modern times, focuses on the transfer of verbs and particles.37 For instance, the suffix -ecatl transferred as -eco to modern Spanish, and the

32 Olko, 46.

33 "Eight Words from Nahuatl, the Language of the Aztecs: Avocado, Chocolate, and More," Dictionary by Merriam-Webster, accessed March 24, 2023.

34 Karen Dakin and Søren Wichmann, "Cacao and Chocolate: A Uto -Aztecan Perspective," Ancient Mesoamerica 11, no. 1 (Spring 2000): 60-62, JSTOR.

35 Instituto Cervantes, "Catálogo de Voces Hispánicas: México, México D.F." [Catalog of Hispanic Voices: México, México D.F.], Centro Virtual Cervantes, accessed March 24, 2023.

36 Petkova, "La Presencia," 49-50.

37 Olko, "Language Encounters,” 38.

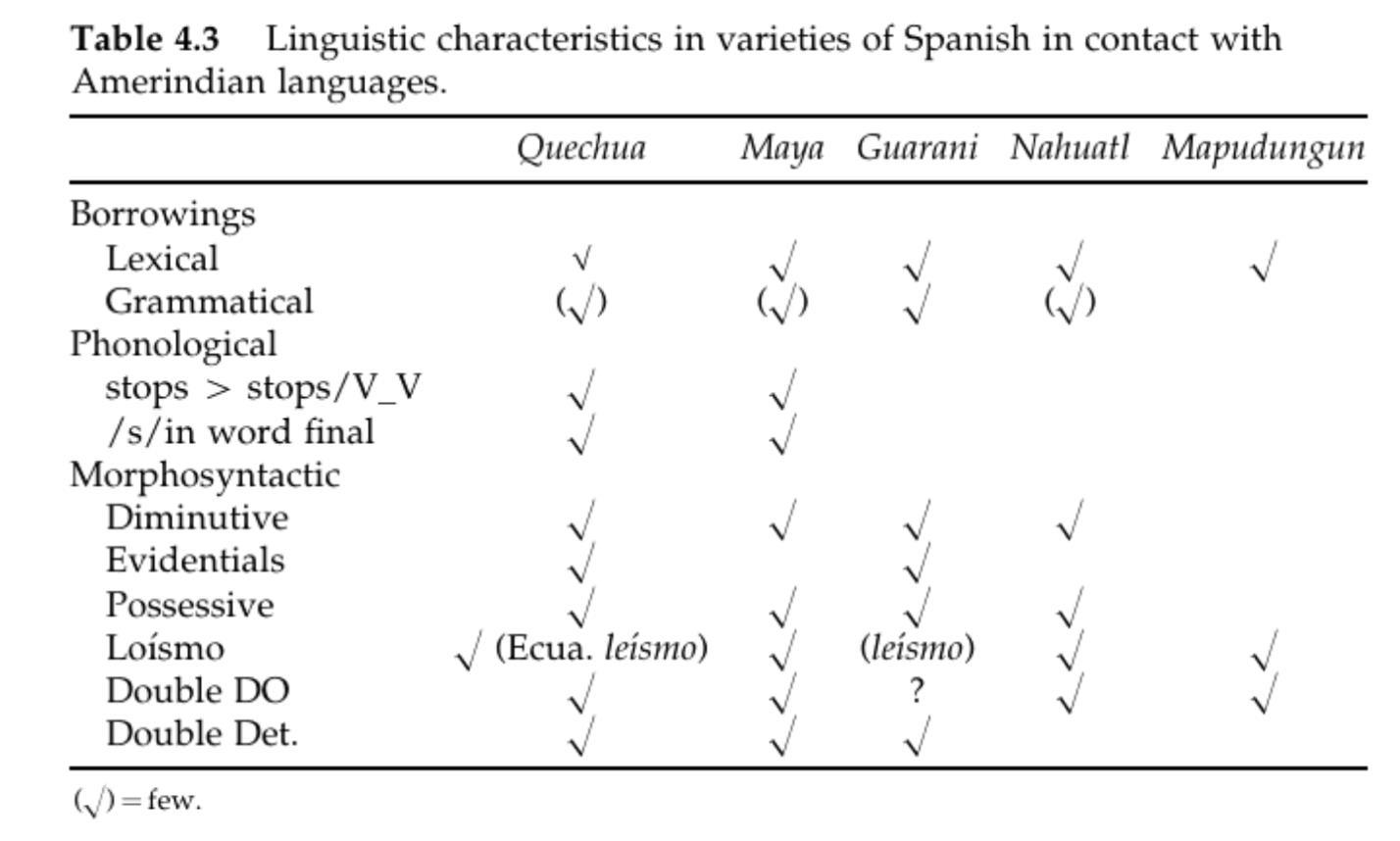

phonetic /tl/ sound from Nahuatl transferred into Spanish as well.38 Through Lockhart’s phases, scholars can study cases of lexical transfer from Nahuatl to Spanish through loanwords, neologisms, and backward borrowing, as well as some cases of grammatical and phonetic transfer. The Nahuatl column below demonstrates language similarities that Nahuatl shares with the Spanish language (see fig. 3):

The table highlights various Indigenous languages and the linguistic elements they have in common with Spanish. Nahuatl shares lexical, grammatical, and morphosyntactic features with Spanish, and Mapudungun shares lexical and morphosyntactic characteristics with Spanish, so this table provides a useful segway into a discussion of what Mapudungun has in common with the Spanish language.

38 Petkova, "La Presencia," 45-46.

39 José Ignacio Hualde, Antxon Olarrea, and Erin O'Rourke, eds., The Handbook of Hispanic Linguistics , 80.

The Mapudungun Language’s Influence on the Spanish Language in Chile

According to Sadowsky, Chilean Spanish’s development is unique compared to other variations of Spanish, due to Chile’s natural geographic separation. For example, this unique development is evidenced by the fact that Chilean Spanish contains ninety-three unique consonantal allophones.40 Scholars have not thoroughly investigated Mapudungun’s influence on Spanish, however, and many past linguists have argued about the true extent of that influence.

Rudolf Lenz, a German linguist who studied Chilean Spanish, authored extensive scholarship on this topic, specifically Para el Conocimiento del Español de América, or For the Knowledge of Spanish in America, and the Diccionario Etimológico de las Voces Chilenas

Derivadas de Lenguas Indígenas Americanas, or the Etymological Dictionary of the Chilean Voices Derived from American Indigenous Languages 41 His theories argue that ten phonetic features characteristic of Chilean Spanish came from the Mapudungun language, but his ideas were later opposed by Spanish linguist Amado Alonso in Examen de la Teoría Indigenista de Rodolfo Lenz, or the Examination of Rudolf Lenz’s Indigenist Theory. 42 In order to disprove

Lenz’s theory, Alonso argued that those phonetic features could not have been derived from Mapudungun in Chilean Spanish because they also appeared in other varieties of Spanish around Latin America in regions without Mapuche populations.43 Sadowsky, however, recognizes that scholars should revisit Lenz’s hypothesis with a more modern lens. To do so, Sadowsky

40 Scott Sadowsky, "Español con (Otros) Sonidos Araucanos: La Influencia del Mapudungun en el Sist ema Vocalico del Castellano Chileno" [Spanish with (Different) Araucanian Sounds: The Influence of Mapudungun on the Chilean Spanish Vowel System], Boletín de Filología 55, no. 2 (July 2020), Gale OneFile: Informe Académico.

41 Sadowsky, "Español con (Otr os)."; Arturo Hernández Salles, "Influencia del Mapuche en el Castellano," Revista Documentos Lingüísticos y Literarios (Universidad Austral de Chile) , no. 7 (January 1, 1981): 34 -36, accessed February 17, 2023.

42 Salles, 35.

43 Salles, 35.

examined all ten of the language features that Lenz attributed to Mapudungun transfer and concluded that although three were unlikely to have been the result of Mapudungun transfer, the origins of four were inconclusive due to the scarce amount of evidence and research surrounding those features, and three were very likely to have been the result of Mapudungun transfer. 44 The three language features that were most likely to have come from Mapudungun include the fricative pronunciation of the /r/ sound, the affricative pronunciation of the /tJ/ sound, and the palatalization of the /k/, /g/, and /x/ sounds when they come before /e/ or /i/.45 Even though Lenz’s theory may not have been entirely correct, the fact that some phonetic features of Chilean Spanish likely have their origin in Mapudungun highlights the fact that the Mapudungun language did indeed impact Chilean Spanish. Furthermore, the fact that four of Lenz’s observations are inconclusive emphasizes the need for more research surrounding Indigenous influence on Chilean Spanish. Additionally, lexical and intonational transfer, as well as morphosyntactic influence, play a role in both Nahuatl-Spanish interaction and MapudungunSpanish interaction, which further suggests that Indigenous languages’ influence on Chilean Spanish requires further exploration.

Regarding lexical transfer and borrowing, Mapudungun has given loanwords to Spanish and Spanish has given loanwords to Mapudungun. However, according to Haspelmath and Tadmor, the Mapudungun language has acted as a symbol of Mapuche heritage and identity, which may explain why other Indigenous languages have contributed more loanwords to Spanish than Mapudungun.46 More specifically, many Mapudungun words are place names in Chile.47

44 Sadowsky, "Español con (Otros)."

45 Sadowsky.

46 Haspelmath and Tadmor, Loanwords in the World's, 1046.

47 Carlos Ramirez Sánchez, Voces Mapuches, 5th ed. (Valdivia, Chile: Editorial Alborada, 1986), 93 -95.

Other loanword examples from Mapudungun to Spanish include poncho, guata for stomach, laucha for mouse, and chuico for large vase, to name a few.48 Additional examples include colocolo for a type of wildcat, pino for a dish with onions and meat, and imbunche for witchcraft or sorcery.49 Since Nahuatl has also given loanwords to Spanish, this furthers the idea that perhaps Nahuatl contact with Spanish can help scholars understand Mapudungun contribution in Chile.

Though Alonso strongly opposed Lenz’s theories, he conceded in 1953 that Mapudungun may have influenced Chilean Spanish with intonational transfer. 50 Rogers explains a specific intonational plateau, or pattern of intonation, commonly found in Chilean Spanish broad focus statements:

They begin with an optional low tonal valley in which all phonetic content is realized at the same low intonational level. The valleys can be as short as two or three syllables or may extend for multiple stressed and unstressed words. The valleys end in a sudden rise on the stressed syllable of the final valley-internal word. The rise continues to a higher pitch level, where the speaker maintains the high F0 for anywhere between two or three syllables to multiple stressed and unstressed words. Finally, the contour ends in a sudden drop. In some cases, this final drop occurs over multiple stressed syllables and/or words,

48 Hualde, Olarrea, and O'Rourke, The Handbook, 93:70.

49 Instituto Cervantes, "Catálogo de Voces Hispánicas: Chile, Santiago" [Catalog of Hispanic Voices: Chile, Santiago], Centro Virtual Cervantes, accessed March 24, 2023.

50 Brandon M. A. Rogers, "Exploring Focus Extension in Mapudungun and Chilean Spanish Intonational Plateaus: The Case for Pragmatic Transfer through Language Contact," in Spanish Phonetics and Phonology in Contact: Studies from Africa, the Americas, and Spain , ed. Rajiv Rao, Issues in Hispanic and Lusophone Linguistics Ser. (Amsterdam, Netherlands: John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2020), 28:294 , ProQuest Ebook Central.

and in other cases the speaker rises above the plateau on the final stressed syllable and falls on all subsequent syllables.51

Here, broad focus refers to sentences that have no emphasis on any specific word throughout the sentence. Rogers provides various diagrams of this broad focus statement intonational plateau pattern with example sentences (see fig. 4).

In Figure 4, readers observe the low tone on para la mayoría before seeing the rise in pitch on the last syllable of mayoría, followed by a gradual drop in tone in the next few words of the sentence.

Readers observe the low tone on pero la infraestructura before seeing the rise in pitch on the last syllable of infraestructura, followed by a very gradual drop before a sudden drop to end the sentence (see fig. 5).

Interestingly, regarding Mapudungun and Chilean Spanish, Rogers also points out that “the plateaus in both languages show the same tendency to expand and retract the sustained high tonal portions to include a variety of content, even entire ideas or concepts.”54 Rogers explains the purpose of these intonational plateaus as “a mechanism for extending focus through which speakers signal the salience of an entire (often syntactically/semantically complex) idea, or strings of stressed words, that together form a phrase-level unit that is one highlighted entity

53 Rogers, 299.

54 Rogers, 318.

rather than simply a variant of broad focus statements.”55 This plateau pattern may have existed in both languages because cases of languages transferring completely novel intonation patterns into another language are scarce, so Rogers proposes that rather than transferring the intonational pattern itself, Mapudungun transferred the purpose of this intonational pattern to expand the focus of sentences and draw attention to every word rather than normally emphasized words. 56

To dive deeper into Chilean Spanish and Mapudungun’s influence on intonation, two case studies of the Spanish language in Cautín and Concepción highlight Mapudungun’s central role. According to Rogers, the Spanish spoken in Cautín, a southern Chilean province, exhibits specific morphosyntactic aspects characteristic of Mapudungun. While this phenomenon may be caused by the introduction of these morphosyntactic aspects by some other means, this theory does not eliminate the idea that Mapudungun may have transferred them. 57 Furthermore, Sadowsky conducted a study of the Chilean city of Concepción and found that even though Chilean Spanish phonologically is the same as other variations of Spanish, Chilean Spanish speakers’ pronunciation of vowels is similar to Mapudungun and different from most other Spanish variations, suggesting that Mapudungun impacted Concepción’s Spanish in that sense.58

Thus, Nahuatl contact with Spanish features neologisms, borrowing of words from Spanish into Nahuatl and vice versa, the transfer of verbs and particles, and some phonetic transfer. Mapudungun contact with Spanish also features lexical borrowing from Spanish to Mapudungun and vice versa, as well as phonetic transfer in specific Chilean regions and intonational similarity. Given past dismissal within the scholarly community surrounding

55 Rogers, 319.

56 Rogers, 319.

57 Rogers, 301.

58 Sadowsky, "Español con (Otros)."

Mapudungun, not much research has been conducted regarding the influence of Indigenous languages on Chilean Spanish, but these preliminary findings suggest that Mapudungun influence on Spanish should not be dismissed.

Language Contact Between Rapa Nui and Chilean Spanish on Easter Island

Following Chile’s annexation of Easter Island in 1888, Chile used the land for cattle before establishing control in 1966 when approximately 400 Chilean officials settled on the island, catalyzing language contact between the Rapa Nui language and Chilean Spanish. 59 Linguistic anthropologist Miki Makihara of Queens College and the City University of New York has authored numerous works about the Rapa Nui language and its interaction with Spanish. Although language shift from Rapa Nui to Spanish is occurring, Makihara argues for the development of “syncretic Rapa Nui speech styles” as the language encounters Spanish, highlighting its influence on the Spanish spoken on Easter Island specifically.60 Since Easter Island was officially annexed in 1888, it presents a unique case of faster language change as opposed to the more gradual case of Mapudungun contact with Spanish.

Makihara explains that speech styles vary depending on whether one’s first language is Rapa Nui or Chilean Spanish. In R1S2 Rapa Nui Spanish, or when a speaker learns Rapa Nui first and Spanish second, features of Spanish and Rapa Nui transferred to create a new variation of the language. First of all, Rapa Nui contains fewer consonants than Spanish, so when R1S2 speakers speak Spanish, they tend to exchange certain Spanish consonants that do not have a direct Rapa Nui counterpart for a Rapa Nui consonant that sounds similar to but does not directly

59 Miki Makihara, "Rapa Nui Ways of Speaking Spanish: Language Shift and Socialization on Easter Island," Language in Society 34, no. 5 (November 2005): 727 -728, JSTOR.; "Rapa Nui," 4.

60 Makihara, 728-729.

correspond to the Spanish one.61 Additionally, the Rapa Nui language does not distinguish between genders, while Spanish pronouns do, so when R1S2 speakers speak Spanish, they may use some Spanish pronouns interchangeably. Lastly, R1S2 speakers tend to use the third person singular Spanish pronouns, él and ella, as well as the present indicative Spanish verb form. 62 On the other hand, R2S1 Rapa Nui Spanish, or when a speaker learns Spanish first and Rapa Nui second, features the transfer of Rapa Nui loanwords and vocabulary.63 So, when studying R1S2 and R2S1 styles, it is clear that Rapa Nui and Chilean Spanish contact features phonetic transfer, grammatical substitution, and the borrowing of loanwords, all aspects of language contact th at Nahuatl exhibited in Mexico to some degree. However, consistent with the substratum and superstratum theory that Nahuatl and Mapudungun demonstrate, Chilean Spanish has gradually become the main language of use on Easter Island as it has in mainland Chile. Rapa Nui culture and language still live today, however, whether that be through these R1S2 and R2S1 speech styles or through more direct efforts to revitalize their culture. For example, even as many Rapa Nui children become fluent in Spanish, they still hear the Rapa Nui language among their relatives, helping them to learn. 64 Furthermore, in 1976, many schools on Easter Island began to include Rapa Nui language classes as part of their course offerings.65 Additionally, in some cases, Chilean influence on Easter Island can be transformed to represent Rapa Nui heritage more accurately. For instance, Tapati Rapa Nui, which means Rapa Nui Week, includes a variety of educational entertainment and

61 Makihara, 733-734.

62 Makihara, 734-735.

63 Makihara, 731.

64 Makihara, 744.

65 Makihara, 743.

interactive opportunities related to Rapa Nui heritage even though the event was first intended to be like a Chilean celebration.66 Lastly, the fact that many children on Easter Island tend to use Spanish does not necessarily mean that they do not value the Rapa Nui language. As Makihara notes, Spanish has become widely spoken on the island, but the children’s ability to blend features of Rapa Nui with Spanish suggests that they are connecting with and appreciating their heritage and the Rapa Nui language.67 Language, despite consisting of nonliving sounds, words, grammar, and tone, possesses a distinct vitality, as well as the ability to grow and change as the world evolves. The rich complexity of language history, specifically the history of the development of Spanish in Latin America and the impact of Indigenous languages, has given rise to debate among scholars about the true origins of modern Spanish in Latin America as well as the contribution of Indigenous languages in Latin America to modern Spanish. Past researchers have conducted extensive research regarding Nahuatl, partly due to the vast number of historical documents and resources available. Mapudungun and Rapa Nui’s impact on Chilean Spanish, however, has received less attention within the scholarly community, and researchers like Amado Alonso have argued against claims that Mapudungun may have influenced Chilean Spanish. Despite this decisive rejection of Mapudungun influence, more recent studies, such as those of Rogers and Sadowsky, suggest that Mapudungun has contributed to Chilean Spanish in terms of loanwords and lexical transfer, as well as intonational, phonetic, and morphosyntactic influence. Makihara’s work also suggests that the Rapa Nui language has contributed to Chilean Spanish through R1S2 and R2S1

Rapa Nui Spanish.

66 Makihara, 750-751.

67 Makihara, 754.

Similarly, Nahuatl contributed to Mexican Spanish by way of loanwords and lexical transfer, as well as some grammatical and phonetic influence. Though Nahuatl and Mapudungun have not influenced Spanish in the exact same way, this contrast is to be expected because the languages and their histories of interaction with the Spanish language vary. The fact that these languages have influenced Spanish in similar ways, however, suggests that Mapudungun has influenced the Spanish language more than previously thought. Additionally, Nahuatl, Mapudungun, and Rapa Nui are still spoken today to varying degrees. Thus, as scholars revisit Indigenous languages in Latin America and reassess Mapudungun influence, it is important to emphasize Indigenous contributions, revitalize Indigenous cultures, and encourage the teaching and learning of Indigenous languages.

Bibliography

Bacigalupo, Ana Mariella. "Mapuche." In Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, 2nd ed., edited by Jay Kinsbruner and Erick D. Langer. Vol. 4. Detroit, MI: Charles Scribner's Sons, 2008, Gale in Context: World History.

"Chile." In Countries of the World and Their Leaders Yearbook 2021, edited by Karen Ellicott. Vol. 1. Farmington Hills, MI: Gale, 2020, Gale in Context: World History.

Dakin, Karen, Claudia Parodi, and Natalie Operstein, eds. Language Contact and Change in Mesoamerica and Beyond. Vol. 185. Studies in Language Companion Ser. Amsterdam, Netherlands: John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2017, ProQuest Ebook Central.

Dakin, Karen, and Søren Wichmann. "Cacao and Chocolate: A Uto-Aztecan Perspective."

Ancient Mesoamerica 11, no. 1 (Spring 2000): 55-75, JSTOR.

Data from University of California, San Diego. "Map of Ancient Mexico." Map, JSTOR.

"Eight Words from Nahuatl, the Language of the Aztecs: Avocado, Chocolate, and More." Dictionary by Merriam-Webster. Accessed March 24, 2023. https://www.merriamwebster.com/words-at-play/words-from-nahuatl-the-language-of-the-aztecs.

Haskett, Robert. "Nahuas." In Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, 2nd ed., edited by Jay Kinsbruner and Erick D. Langer. Vol. 4. Detroit, MI: Charl es Scribner's Sons, 2008, Gale in Context: World History.

. "Nahuatl." In Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, 2nd ed., edited by Jay Kinsbruner and Erick D. Langer, 767-68. Vol. 4. New York City, NY: Charles Scribner's Sons, 2008, Gale in Context: World History.

Haspelmath, Martin, and Uri Tadmor, eds. Loanwords in the World's Languages : A Comparative Handbook. Berlin, Germany: De Gruyter, 2009, ProQuest Ebook Central.

Hickey, Raymond, ed. The Handbook of Language Contact. 2nd ed. Blackwell Handbooks in Linguistics Ser. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2020, ProQuest Ebook Central.

Hualde, José Ignacio, Antxon Olarrea, and Erin O'Rourke, eds. The Handbook of Hispanic Linguistics. Vol. 93. Blackwell Handbooks in Linguistics Ser. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2012, ProQuest Ebook Central.

Instituto Cervantes. "Catálogo de Voces Hispánicas: Chile, Santiago" [Catalog of Hispanic Voices: Chile, Santiago]. Centro Virtual Cervantes. Accessed March 24, 2023. https://cvc.cervantes.es/lengua/voces_hispanicas/chile/santiago.htm.

. "Catálogo de Voces Hispánicas: México, México D.F." [Catalog of Hispanic Voices: México, México D.F.] Centro Virtual Cervantes. Accessed March 24, 2023. https://cvc.cervantes.es/lengua/voces_hispanicas/mexico/mexicodf.htm.

Makihara, Miki. "Rapa Nui Ways of Speaking Spanish: Language Shift and Socialization on Easter Island." Language in Society 34, no. 5 (November 2005): 727-62, JSTOR.

"Mapuches." In Americas, 2nd ed., edited by Timothy L. Gall and Jeneen Hobby. Vol. 2 of Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life. Detroit, MI: Gale, 2009, Gale in Context: World History.

Olko, Justyna. "Language Encounters: Toward a Better Comprehension of Contact -Induced Lexical Change in Colonial Nahuatl." Politeja: Europe-Latin America Cultural Encounters, no. 38 (2015): 35-52, JSTOR.

Penny, Ralph. "Variation in Spanish America." In Variation and Change in Spanish, 136-73. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2000, ProQuest Ebook Central.

Petkova, Ingrid. "La Presencia de los Nahuatlismos en el Español de México desde un Enfoque Diacrónico." Acta Hispanica 22 (2017): 45-53, ProQuest.

"Rapa Nui." In Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life, 3rd ed. Vol. 4. Farmington Hills, MI: Gale, 2017, Gale in Context: World History.

Rogers, Brandon M. A. "Exploring Focus Extension in Mapudungun and Chilean Spanish Intonational Plateaus: The Case for Pragmatic Transfer through Language Contact." In Spanish Phonetics and Phonology in Contact: Studies from Afr ica, the Americas, and Spain, edited by Rajiv Rao, 293-323. Vol. 28. Issues in Hispanic and Lusophone Linguistics Ser. Amsterdam, Netherlands: John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2020, ProQuest Ebook Central.

Sadowsky, Scott. "Español con (Otros) Sonidos Araucanos: La Influencia del Mapudungun en el Sistema Vocalico del Castellano Chileno" [Spanish with (Different) Araucanian Sounds: The Influence of Mapudungun on the Chilean Spanish Vowel System]. Boletín de Filología 55, no. 2 (July 2020), Gale OneFile: Informe Académico.

Salles, Arturo Hernández. "Influencia del Mapuche en el Castellano." Revista Documentos Lingüísticos y Literarios (Universidad Austral de Chile) , no. 7 (January 1, 1981): 34-44. Accessed February 17, 2023.

http://www.revistadll.cl/index.php/revistadll/article/view/73.

Sánchez, Carlos Ramirez. Voces Mapuches. 5th ed. Valdivia, Chile: Editorial Alborada, 1986.