2015-16

JOHN NEAR GRANT Recipient

Graphic Soldiers: Popular Sentiment as Reflected in Captain America and Spider-Man

Sadhika Malladi, Class of 2016

GRAPHIC SOLDIERS:

POPULAR SENTIMENT AS REFLECTED IN CAPTAIN AMERICA AND SPIDER-MAN

Sadhika Malladi 2016 John Near Scholar

Mentors: Ms. Katy Rees, Mrs. Lauri Vaughan April 11, 2016

Two of Marvel Comics’ most successful and well-known superheroes are Captain America and Spider-Man. While different in their personalities and methodologies, the two heroes were forged as relatable symbols of hope as it was defined in different time periods.

Created during World War II, Captain America stood as a bastion of nationalism and challenged the Axis Powers in his adventures. On the other hand, Spider-Man epitomized the postwar period of uncertainty and fought enemies working for the Soviet Union. Investigating the influence of the social, political, and economic circumstances of the time on the stylistic decisions made in the comic books may offer a novel perspective on popular sentiment regarding foreign and domestic powers. The story of Captain America, created during the Golden Age, reflected growing popular support for entry into WWII, while the Silver Age hero Spider-Man was a manifestation of growing fears of the booming military-industrial complex in relation to the Cold War.

Comic books closely follow the readership’s interest in the content and themes to maintain consumption. Therefore, the strongly typed good and evil characters of comic books often align with prevalent political, economic, and social ideologies While modern comic books are associated with a younger, largely male audience, they initially appealed to a much broader audience. A study conducted in 1945, during one of the peaks in comic book popularity, found that nearly half of all Americans consumed the entertainment medium, with nearly even percentiles of young girls and boys in the readership.1 Furthermore, 41 percent of men and 28 percent of all women between the ages of 18 and 30 purchased comic books at the time, indicating that the comics had wide appeal.2

Inspired in large part by the pulp magazine industry, comic books have fluctuated in popularity and content since their first appearance in the 1930s.3 The amount of disposable

income available to the average American family, public interest in the content conveyed in comic books, and the evolution of stereotypes used to portray characters contributed to the trends in comic book consumption.4 To encapsulate each of these factors as they vary with time and inform the creation of popular heroes, historians classify comic books roughly into the Golden Age, the Silver Age, the Bronze Age, and the Modern Age.5

The Golden Age, which began with the 1938 debut of Superman in Action Comics #1, ran through World War II and the immediate postwar period.6 Popular sentiment regarding the United States’ role in the war shifted rapidly during this time period.7 The archetypal superhero took shape as a man of virtue who defended helpless civilians against corruption and danger. Comic books were used on the war front and at home to reinforce narratives of entry into the war as an ennobling and necessary action against prevailing evil forces.8 Captain America, in particular, doubled as a humble and obedient soldier playing his role in the war effort as well as a noble superhero, emphasizing his ability to put aside his ego for the larger American mission. The graphical rendering of characters and their developments in popular comic books, such as Super-Man and Captain America, portrayed a pro-war stance, sometimes subtly and often times blatantly. As the first enduring time period during which multiple comic books became wildly popular, the Golden Age established comic books as a culturally relevant and influential medium of entertainment. However, when the war ended, the United States held few clear enemies to define villains, so comic books scrambled to maintain interesting and relatable storylines.9 Moreover, in 1950, the United States convened a special Senate Committee to investigate trends in increased amounts of organized crime, and the glorification of criminality in comic books became a topic of discussion.10 The Golden Age began to decline.

With the publication of Frederick Wertham’s Seduction of the Innocent in 1954, the content of comic books again came under scrutiny by the government and cautious parents alike.11 The widely read book accused the comic book industry of planting violent and rebellious thoughts in children that resulted in the marked increase in juvenile delinquency.12 As per the recommendation of the Senate, the industry self-imposed the Comics Code to place restrictions on the depiction of gore, violence, nudity, sex, the triumph of antisocial evil, and unflattering portrayals of law enforcement 13 As the code was negotiated, comic books diverged in subject, discussing humor and romance in a desperate effort to remain in public favor.14 Because the code was not set by the government and was a self-regulating measure in the industry, comic book writers and artists could choose whether to abide by its rules or not.15 A majority of the comics did follow the code, and adult readers of these stories felt that the censorship hindered plot development.16 As a result, comic books became an entertainment form primarily for younger audiences, and they lost popularity as publishers sought to reconcile popular archetypes with modified and censored storylines.17 As such, the Comics Code shifted content to cater toward a younger reader demographic, which helped stabilize the industry and created a structure within which the well-known elements of comic books, heroes and villains, could be reborn.18

The revival of The Flash in DC Comics’ Showcase #4 marks the start of The Silver Age in October 1956.19 While DC Comics revived the idea of superheroes, Marvel Comics capitalized on popular sentiment by creating uncertain and inherently flawed characters who had been thrust into the spotlight by coincidence.20 This new breed of superheroes struggled to balance their daily lives and obligations with the added burden and responsibility of their powers. Another common facet of Silver Age comics is the derivation of superpowers from radioactive or vaguely scientific experiments gone wrong.21 Common heroes who follow this

trend include The Incredible Hulk, the Atom, and Ant-Man. As such, the Silver Age is sometimes also referred to as the Atomic Age, reflective of the mystery surrounding the development of nuclear power and the further proposals of hydrogen bombs during the period.22

As a response to the Comics Code, subversive comics were published independently, known as “underground comix. ”23 The Silver Age was closely followed by the Bronze and then Modern Ages, which featured a return to the archetypal and popular superhero figures and classic storylines, as well as adaptations of a paper medium to film. As the artistic repression of the Comics Code Authority eased up, darker plot elements such as drug use and poverty returned 24

Introduction to the Golden Age

In 1938, tensions in Europe were reaching a fever pitch once again following World War I. The Senate Nye Committee hearings concluded that American involvement in World War I was driven by banking interests, and H.C. Engelbrecht’s The Merchants of Death further exemplified the dangers of allowing American businesses to interact with members of foreign wars.25 The United States passed a series of Neutrality Acts in 1935, 1936, and 1937, intent on preventing American business from getting entangled in European affairs and compromising the neutral position of the nation.26 Thus, the argument for isolationism and non-interventionism grew stronger and the issue of foreign entanglement came to the forefront of the public’s attention.27

While isolationism and non-interventionism largely prevailed, figureheads of the comic book scene adopted a firm pro-war stance. From Captain America to Super-Man to Captain Marvel, superheroes increasingly conflated a moralistic tone with a nationalistic one, implying that America stood as a bastion of fairness and democracy and therefore must act to protect and propagate such ideas.28 The rogues gallery, the villains whom the superhero traditionally battles,

became increasingly composed of deranged people brainwashed by the Axis powers.29 Artists stylized villains with stereotypes that contributed to the dehumanization of the enemy.30

Fearful of German power and desiring to assist longtime ally Britain, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt requested a “cash and carry” policy to replace the Neutrality Acts and avoid direct American involvement in the war while providing assistance to Allied nations.31 As the war escalated, American policy shifted to provide increased support to Allied nations. The LendLease Act of 1941 allowed the United States to provide aid to Allied nations in exchange for leases on naval and army bases in Allied territory, effectively ending the commitment to neutrality.32 While the United States had begun actively supporting the Allied Powers, it had not officially declared war yet. However, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in December 1941, killing and injuring innocent American civilians.33 In response, the United States declared war on Japan and entered World War II. Japanese-Americans came under immediate suspicion, thought to have thwarted American defenses and to be complicit in an invasion of the West Coast.34 The panic and fear that people felt towards the Axis Powers’ unstoppable agenda thus extended to Americans, as President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 in 1942, ordering that all Japanese-Americans report to harsh internment camps.35 Roosevelt stated that the order was written in an effort to “[protect] against espionage and against sabotage to national-defense material, national-defense premises, and national-defense utilities.”36 Due to the personal nature of the attack on Pearl Harbor, one of the largest direct military operations against civilians, popular sentiment quickly turned against the Axis Powers, casting them as clear enemies in comic books.37

The entire nation shifted toward a war economy, calling for an all-hands-on-deck effort to supply the war. The War Production Board halted production of consumer products and

redirected labor toward the war effort.38 To earn the support of citizens who felt detached from a distant battlefield, the Office of War Information distributed propaganda to mobilize the citizens. Comic books were a key tool in official and informal propaganda in popular culture was enforcing stereotypes about the Axis Powers, as was prevalent in comic books.39

In August of 1945, after Germany had surrendered, the United States dropped two atomic bombs on Japan. Showcasing power that had never been attained by a nation before, the United States executed massive destruction in Japan. The secrecy of the development of the atomic bomb combined its destructive power contributed to pervasive fears about government spending on defense and the misuse of scientific advancement.40

Comic books began implying that the United States should play an active role in formulating a postwar world, overwhelmingly supporting public opinion. Superheroes clad in American colors, such as Captain America, rescued damsels in distress and young people brainwashed by villains.41 Partly because the entertainment value was tied to the action in the book, comics never implied that a non-interventionist approach to foreign relations might have been more noble.42 Furthermore, comic book superheroes were created to satisfy the escapist fantasies of a population working toward distant war effort.43 As such, the superheroes’ direct involvement in the war was appealing to readers.44 The people being saved always needed and appreciated the help they received, and the superhero would emerge unscathed from most ordeals.45 Comics began portraying an actively interventionist United States that provided aid in effort to maintain and propagate democracy even before the nation openly adopted that stance. In 1947, the Truman Doctrine formalized American involvement in global affairs by stating that the United States would support people resisting subjugation at the hands of outside influences.46 At the time, the doctrine established the United States as an active opponent to the status of USSR

satellite states and the so-called domino theory of communism by laying the foundation for containment policy.47

The Golden Age saw the rise of comic books and their influence in the nation. They were read widely from households to war fronts, and as such, they often imbued entertaining, actionpacked stories with a moralistic and patriotic tone.48 As the United States was embroiled in another violent war, comic books provided an optimistic commentary that established a moral justification for the war and encouraged every citizen to participate.49 To reinforce that message, comics often incorporated racist stylistic techniques that established the United States as a prevailing good in the face of the evil influence of the Axis powers.50 As one of the most popular heroes of the Golden Age, Captain America embodied this perspective throughout his adventures.

Introduction to Captain America

One of the most archetypal patriotic superheroes is Captain America, who debuted in March 1941 in Captain America Comics #1.51 Wildly popular during the Golden Age, Captain America emerged among the first generation of superheroes, idealized as the quintessential American soldier. The two primary writers on the early issues of the comics were Joe Simon and Jack Kirby, who consciously constructed Captain America as a political symbol.52 Simon explicitly commented on the purpose behind the character, claiming "the opponents to the war were all quite well organized. We wanted to have our say too.”53 In the cover of his debut issue, the authors boldly and purposefully depict him as a clear opponent to Adolf Hitler, whose moral deficiencies were widely recognized despite public uncertainty over American entry into the war.54 (See Fig. 1) In 1940, a propagandist film entitled To Hell with Hitler was released, the

poster showing Hitler being punched. (See Fig. 2). Similar stereotypical elements are highlighted in both cultural depictions, particularly the emblematic moustache.

Behind the main scene of Captain America punching Hitler, a screen shows an American ammunitions factory being bombed. The surrounding Nazis appear confused and their bullets ricochet harmlessly off Captain America. The cover’s overt establishment of Hitler as a foolish and easily conquered enemy for Captain America to beat clearly illustrates the authors’ support for entry into World War II and stereotypical commentary against the Germans, who are shown as befuddled and disorganized.

In addition to introducing a mature and patriotic superhero, Captain America Comics #1 also debuts Bucky, Captain America’s plucky young sidekick. Bucky represents a patriot of the latest generation, intended to connect with youth.55 By displaying enthusiasm and earning praise from others for his involvement in defeating villains, Bucky portrays a pro-war stance and suggests nobility in military service. The nation as a whole also believed that all citizens, including adolescents, ought to participate in the war effort in some manner, regardless of their abilities.56

Captain America serves as an emblem summarizing the romanticized American identity as it existed in 1941. Eager to serve his nation, Steve Rogers enters the draft. However, because of his asthma and generally frail physique, he is rejected repeatedly from the army. Through hard work and determination, he overcomes his innate shortcomings, primarily physical weakness, to realize his patriotism in the service of America.57 Unlike static symbols of America, Captain America provides a dynamic narrative that shifts and morphs with the rapidly changing landscape of American popular sentiment regarding domestic and foreign policy. When American popular sentiment turned against Japanese-Americans after Pearl Harbor, Captain America Comics quickly shifted to a set of anti-Japanese narratives, the first of which was showcased in the thirteenth issue published in April 1942.58 (See Fig. 3). The cover shows

Captain America punching Hirohito, who is portrayed with bestial qualities like jagged teeth, reminiscent of a predatory animal. Furthermore, at their feet, the scene of the Pearl Harbor bombing plays out, and a prominent logo urges readers to “Remember Pearl Harbor.”

Figure 3. Avison, Al and Don Rico. Captain America Comics #13. 1942.

Captain America reminds readers that the Japanese attacked the United States first, justifying entry into the war. After the bombing, President Roosevelt addressed the nation in December 1941, clearly asserting that “[the United States] will not only defend [itself] to the uttermost, but will make it very certain that this form of treachery shall never again endanger [it].”59 Roosevelt thus implies that the United States must enter the war to preserve national safety. Furthermore, by suggesting that Japan betrayed the nation through the act, Roosevelt set the tone for sentiments against Japanese-Americans. He also noted the duplicitous politics of the

Japanese government, because the United States was “still in conversation with [the Japanese] government and its emperor looking toward the maintenance of peace in the Pacific” at the time of the attack.60

The Captain has no supernaturally gifted powers, and the super-serum that granted him powers was developed through a governmental scientific program.61 The story portrays military defense spending as a gift to soldiers who sought to make a change but could not alone.62 Furthermore, the creation story of Captain America suggests that American intervention and active development and deployment of the military is required to win World War II. As such, the comic makes a case for the foreign aid that broke from non-interventionist policy and entangled the United States in the war. The hope and enthusiasm with which Captain America provides a service to his nation establishes him as a nationalist and a defender of democracy.

Captain America is known for his shield emblazoned with patriotic colors. Symbolically, he is one of the few superheroes to have a defensive tool. Roosevelt’s speech at Pearl Harbor similarly cast the United States’ involvement and strong nationalism as a mere defense against the deception and aggression of the Japanese 63 While the Captain often uses his shield to protect himself, he also throws it effectively, protecting others and knocking out enemies. The United States’ increasingly prominent role in discussions of formulating a postwar world, evidenced by the Atlantic Charter, similarly casts defense in a more aggressive light.64 In 1941, the United States and Great Britain jointly established eight principles in the Atlantic Charter that they would uphold to help define a postwar world.65 The transition of United States policy from noninterventionism to active participation was thus gradual.

Captain America acts as an antithesis to the contemporaneous Superman, who was borne to Earth from an alien planet and resolved to protect humanity, much like the narrative of a

hardworking immigrant. Unlike Superman, Captain America was created by the nation and seeks to serve it. He is the direct product of the evolving military-industrial complex, set to demonstrate the supposedly inevitable success of American foreign policy and its role in enriching American ideals such as democracy.66

Captain America Comics #2: The Ageless Orientals

While the first released issue of Captain America Comics established the premise of the series, the second issue provided a glimpse of the Captain in action with Bucky, his adolescent sidekick who served as a relatable figure for young readers enamored with the war 67

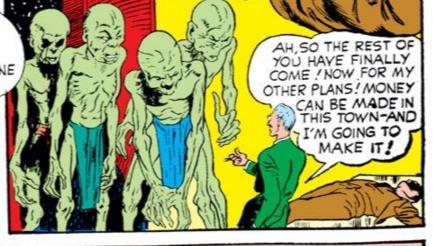

One of the most common enemies that Captain America was forced to take on was Orientals. The first issue focused on Germans, and the second focuses on Japanese or Chinese people, classified generically as Orientals. This narrative focuses on the Captain’s assault on socalled Oriental monsters. Infamous for being unstoppable, the monsters are shown as emaciated, bestial figures. (See Fig. 4). They drool and their eyes are lifeless. Moreover, they have no individual identities – all of the monsters act together, and they skulk about the room. The depiction of the monsters illustrates disgust with and hatred of the increasingly aggressive Japanese power as it stood in 1941. Although the Japanese had not attacked Pearl Harbor by the time of the publication of this issue, popular sentiment clearly ran against the Japanese.68 Propaganda posters of the series “Tokio Kid Say” were installed in many factories to urge workers to adopt conservation practices, showing a Japanese person with animalistic qualities like fangs and a deformed posture.69 (See Fig. 5). Drooling, the boy speaks in broken English, undermining his intelligence.70 The knife behind his back further reinforces perception of the Japanese as aggressive and ruthless, inspired in part by the attack on Pearl Harbor 71 Similarities

in propaganda and comic book depictions of the Japanese demonstrate the role that comics played in influencing and propagating stereotypes and vice versa.

Racist and nativist sentiments are further illustrated through the language in which they communicate, which looks like chicken scratch. (See Fig. 6). These panels and numerous others featuring the Japanese figures convey stereotypes through their emaciated figures, squinting eyes, and hunched postures.

The monsters are shown to be under the control of a man named Benson. Benson has the same stern expression, deformed mouth, and wrinkled skin as Hitler did in the first issue (See Fig. 7). The demeaning depiction of Japanese or Chinese people is completed by the ultimate weakness discovered by Captain America and Bucky: sound. An exploding grenade cannot break the skin of these invincible monsters, but the deafening sound kills them. Their lack of sophistication further dehumanizes the characters in the same way that propaganda did.

Thebetween Bucky, Agent Betty, and Captain America suggests that Agent Betty does not belong in the battlefield. Similarly, during the war, women were necessary but still relegated to secondary roles in the effort.72 Agent Betty works for the United States government, furthering the notion of a place for every person in the patriotic war effort. However, she is essentially futile, wandering accidentally into a situation from which Captain America must rescue her.73 He insists that she go back home and stays out of danger, despite being a fully-grown woman, while he and Bucky, an adolescent boy, continue their quest.74 Bucky, it should be noted, is similarly useless in many scenes, often injuring himself and highlighting the Captain’s bravery and abilities. However, the notion of keeping women off the fighting front lines while allowing young men to join the effort is clearly echoed in these two characters.

While Captain America’s heroics are a central theme of the comic book, his true identity as Steve Rogers is also featured when Captain America transitions back to a humble soldier. (See Fig. 8). Dressed in normal clothes, Steve Rogers sits outside his tent, whittling. Portraying Captain America as a noble hero who fights in the background without desire for recognition adds to the blue-collar nature of the hero. His transition into just another person in the war machine empathized with the plight of the workers and soldiers who would read the comic. To the many Americans who worked extra hours and supported households on war rations, seeing the Captain fade into Steve Rogers provided a sense of relatability and evoked the American ideal of civic virtue. Captain America provided both a hopeful daydream of becoming a hero and an inflated sense of involvement in the war effort despite the lack of recognition.

The episode ends with an advertisement for the Sentinels of Liberty, a program that allows people to send in money to receive a badge, made of “the same metal used in police and firemen badges” that would signify their participation in the efforts of Captain America and Bucky to “[rid] the U.S.A. of traitors who wish to destroy it.”75 The Sentinels of Liberty in many ways mirrored commercials for war bonds that sought to earn Captain America, and the ideals for which he fought, a loyal following. By relating people closely with Captain America, the Sentinels of Liberty gave people the sense that they were directly involved with his battles, which were proxies for World War II.

The early issues of Captain America Comics introduce a central superhero who obediently and fearlessly undertakes the role he is given in the war effort. As popular culture historian Dittmer asserts, the “characterization [of Captain America] as an explicitly American superhero establishes him as both a representative of the idealized American nation and as a defender of the American status quo.”76 By combatting Soviet threats and advertising his democratic ideology, Captain America serves as an important, relatable symbol to Americans

seeking a concrete expression of ideas that had drawn them into the war. As such, Captain America epitomizes popular sentiment during World War II.

Introduction to the Silver Age

The Silver Age addressed many postwar concerns held by Americans about the growing influence of the Soviet Union, the tension between democracy and communism, and the rapid development of destructive technology. Though the Second Red Scare and increasing fear and misconceptions about nuclear power technically occurred during the Golden Age, comics did not address these issues until the Silver Age because of the shift in content to humorous and romantic plots that avoided controversial topics.77 However, with the booming popularity of Superboy in the early 1950s, one of the only successful superhero titles after WWII, many comics writers sought to incorporate adolescent heroes who resonated well with their audiences.78 The Silver Age began in 1956 with the reappearance of The Flash, remodeled as a police scientist who gains powers by accident, but comic books tended to address issues in the early 1950s, including the growth of the Soviet Union, as well.79

In 1949, the polarization between the democratic west and the communist east became apparent through the ratification of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), a group of twelve nations committed to respond to an attack on any member.80 A notable break from the non-interventionist policies of the pre-WWII period, the formation of NATO spurred the creation of the Warsaw Pact in 1955.81 These two organizations divided the world into democratic and communist entities, setting the stage for the opposing sides of the Cold War, which would be strongly typed into heroes and villains in contemporaneous comic books. Misinformation and inflammatory rumors about communism influenced American sentiment 82 The American public largely believed in a worldwide communist conspiracy that asserted cooperation between Mao

Zedong of Red China and Joseph Stalin of the Soviet Union.83 The perceived efforts of communist nations to unite and impose their dogma on the rest of the world was one of many factors that turned Americans against their former allies in the Soviet Union.84

The Second Red Scare and McCarthyism, movements that began in the 1950s and informed American opinion and policy throughout the Cold War, further cemented anticommunism in the public.85 Paranoia of communism being a direct attack on American safety grew with evidence of espionage within the nation. 86,87 Such paranoia was not entirely unfounded, however, as certain cases, including the trial of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, uncovered American citizens as Soviet spies.88 Furthermore, the FBI illegally searched Amerasia, a communist newspaper published in the United States, and discovered classified documents, such as reports on the military powers of other nations.89 The earlier formation of the Central Intelligence Agency helped alleviate fears, but the American people were still concerned about a potential compromise to their democracy.90 Paranoia about insiders leaking confidential information to the United States’ enemies was also seen in comic books, such as in Amazing Spider-Man #2 when the Terrible Tinkerer sends American military communications to the Soviets. Villains disguised themselves as Americans, only to reveal themselves at a crucial moment and wreak havoc.

Wartime measures, such as the incarceration of Japanese-Americans and the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s unofficial search for subversive activity, had compromised civil liberties in favor of national security.91 The notion of a loyal “American” was solidified and idealized in this time period, as seen with the Golden Age trends in comic books.92 Frustration with the discovery of information and the inability to prosecute the apparent criminals, as seen in the FBI case against Amerasia, was one of many driving factors in the rise of vigilantism.93

Spider-Man and other Silver Age heroes often entered into offices and homes without warrants and collected evidence that police officers could otherwise not access. The shift toward a law enforcement system that allowed and even encouraged the violation of civil liberties in a quest to maintain national security in the midst of communist threats thus carried through into comic books and informed the characters of many heroes.

The compromise of civil liberties was further illustrated in the government’s lackluster response to the Civil Rights movement during this period. In all public and private aspects of life, from housing to movies to education, blacks struggled in the postwar period despite gaining opportunities in the wartime economy.94 Comic books largely neglected the issue of race, catering to a largely white audience. However, in the late 1960s, Marvel published the first African-American superhero, The Falcon, focusing on his American identity as it interacts with his African ancestry.95 The Falcon, or Sam Wilson, travels to a remote island in response to a request for a hunting falcon.96 He discovers the occupants to be Nazis, working with Red Skull, a common Nazi archenemy of Captain America.97 Unlike Captain America, who simply fights battles, The Falcon chooses to remain on the island and organize the natives who have been enslaved by the Nazis.98 In fighting Red Skull, The Falcon establishes himself as an American who protects and propagates democratic ideas, but his connection with the island natives references his African ancestry in a subtle yet empowering way.99

The postwar period was also characterized by a growing fear of technology as it might be used or abused in military conquests. The secrecy of the atomic bomb and the devastating effect it had on Japan had shocked many Americans, but the realization that the Soviet Union had developed one a few years later incited fear among Americans.100 Radioactivity became a fascinating topic to research and explore, because it had a seemingly profound though largely

unknown effect on people.101 The focus on radiation and how it affected the lives of superheroes and villains alike led to the moniker of the Atomic Age for this time period.102

The development of the atomic bomb had been largely supported by scientists and politicians alike, but the introduction of designs for a much more powerful hydrogen bomb prompted concern from many parties. Scientists like Albert Einstein, and politicians like James Conant who served on the Atomic Energy Commission, opposed the hydrogen bomb because of the moral and physically destructive consequences of such power.103 Although comics sought to understand the role that such power can play in the hands of the wrong people, they also perpetuated misconceptions about the scientific theories behind them. In order to create more engaging and action-packed narratives, comic books often exaggerated the effect that radioactivity had on people while downplaying the high security under which such volatile material was kept, as was exemplified by Doctor Octopus in Amazing Spider-Man. 104

Growing uncertainty in the American public, brought about by the ideological challenge of communism, threats of subterfuge, and a development of science beyond common understanding contributed to and informed comic book content during the Silver Age. Although readers were generally younger than in the Golden Age, comic books continued to address social issues, albeit with a more simplified perspective.105 Generally, superheroes of the Silver Age came into their powers by chance, as opposed to the nobility of the Golden Age, and were fallible.106 Though they had generally good intentions, they were far from perfect and struggled with many of the same issues in daily life as ordinary Americans Heroes were thus more realistic and less idealized than in the Golden Age.

Introduction to Spider-Man

Published in March 1963, Spider-Man represents a combination of public fears regarding scientific experimentation and advancement, the younger generation’s increasing desire to take a more active role in political affairs and the comic industry’s movement toward fallible superheroes who emulate realistic adolescents.107 As an ordinary boy struggling with typical high school problems, Peter Parker resonates with the audience. Because he stumbles accidentally into his powers, he appeals further to the public who wishes to see the power of science in the hands of common people as opposed to under the jurisdiction of elite and governmental forces.108

Emphasizing Peter Parker as a playful superhero, excited by his powers and somewhat irresponsible at times, epitomizes the Silver Age theme of fallible heroes.109

While Peter is a typical boy at first, he is alienated from his friends and family as a result of a radioactive spider’s bite, which imbues him with web-spinning abilities. The newfound power consumes his life as he seeks solitude to understand his capabilities. Because he has to keep his powers a secret, Peter grows distant from his aunt, his only living family member

Unlike Captain America, whose secret identity served as a source of comic relief and dramatic irony, Spider-Man must learn to reconcile the isolation of his secret with the relationships he values. Furthermore, Peter himself struggles to understand how he can be timid as an ordinary teenager and fearless as a superhero. Themes of alienation and a quest for identity pervade the series, mirroring the younger generation’s disillusionment with the wars of their parents and their fractious political identity as the civil rights movement transitioned into the 1960s.110

Peter’s interest in science is evident, as he often appears as a bookish character. His scientific prowess comes in handy when fighting villains such as Doctor Octopus, who is a celebrity for his scientific knowledge and serves as a role model to other aspiring scientists.

Similarly, the American public sought to understand the new technologies being developed as a part of the rapidly accelerating space race with the Soviet Union.111 Another common theme in Spider-Man that sharply contrasts with Captain America is the media’s perception of his influence on society. The Captain is welcomed as a national hero who defends the average man selflessly. Investigations into his identity are half-hearted as long as he continues to rescue others from distress. On the other hand, Spider-Man is seen as a public menace who causes damage and interferes with police work. This image is perpetuated by Mr. Jameson, who uses his position as an editor at a prominent newspaper to continually deface Spider-Man as a vigilante who is a bad influence on the younger generation.

One of the most shocking and harrowing storylines in Spider-Man is the death of Uncle Ben in the first issue. To make money initially, Peter would don his Spider-Man costume and enter fighting rings. Disillusioned with the world as an orphan and because of his family’s financial hardships, the Spider-Man who enters the ring is selfish. He lets a fleeing thief escape, not feeling personally responsible to stop him, but later finds his Uncle Ben robbed and killed by that same thief. The first issue then concludes with the famous adage: “with great power there must also come – great responsibility!”112

Ironically, Mr. Jameson publishes and capitalizes on Peter Parker’s high quality pictures of Spider-Man. Several points are notable in this transaction. Firstly, Peter still needs to earn an income to support his aunt, reinforcing one of the Silver Age themes of the inexorable burden of daily life as it inhibits the growth of young adults Captain America served in the army, but he was able to leave his position whenever necessary. On the other hand, Spider-Man must continue to take care of his aunt while fulfilling the new responsibilities his power places on him. Furthermore, Spider-Man acts alone, and his family is never a main storyline in the comics.

In the first issue, Peter is shown as a fallible superhero. He struggles to understand the place for his new powers in his life. Unlike Captain America, who is driven by American ideals and seems to have pure intentions at every turn, Peter is forced to be selfish at times to support his aging aunt and complete his education. By moving away from the idealism of Captain America and his ability to save everyone, The Amazing Spider-Man portrays a more realistic storyline that appealed to adolescents attempting to find their personal and social identities in a rapidly changing landscape.

The Amazing Spider-Man #3: Doctor Octopus

When Spider-Man begins to settle into his power and newfound responsibilities, he encounters the problem of hubris. As an adolescent suddenly gifted great power, he often uses his skills to impress people for personal gain. However, in the Silver Age, superheroes were demonstrably fallible. As the first villain to effectively disarm Spider-Man, Doctor Octopus places limits on Spider-Man’s abilities in a way that Captain America did not experience 113 He uses metal arms to conduct nuclear experiments from a distance, and he explicitly notes his power over the radiation that everyone fears. (See Fig. 9). As a result of an experiment gone wrong, Doctor Octopus’ contraption has adhered to his body. (See Fig. 9). In addition to the physical damages, his mind is now more aggressive due to the radiation, and he grows paranoid of his caretakers. Scientifically, it was known that the effects of radioactivity could be avoided by lead suits.114 However, to embellish the story and capitalize on public misconceptions of the technology, the comic book portrays radiation as an unseen, unstoppable force that corrupts.

Doctor Octopus’ creation story reflects public sentiments about nuclear power during the time. There was a vague understanding of the dangers of radiation and its association with nuclear experiments, but also a fear of radiation as an indomitable force.115 As opposed to electricity or water, which could be contained in wires or channels, the destructive force of radiation moved through the air and could not be seen, felt, or heard. However, people felt that harnessing and controlling nuclear power would put the USA above USSR in an incalculable way.116 Given that both countries had developed nuclear bombs that showcased immense power, people feared the destructive capabilities of weapons based on similar and improved technology.

However, with the secretive nature of experimentation and the subsequent enigmatic discourse on nuclear power in the public, people were concerned about who had access to this newfound technology.117 In the hands of one man, as Doctor Octopus demonstrates, radioactivity and nuclear power could be the most destructive force the world had seen to date. All the checks put in place by the government could not help curb the influence held by that one man. Doctor Octopus even blatantly claims: “I have the right to do anything – as long as I have the power!”118 To gain access to the largest known concentration of nuclear power, Doctor Octopus simply

unlocked a single door without oversight. Fears over protecting nuclear technology to maintain secrecy and public safety are exemplified in the Doctor’s apparent omnipotence.119

When Spider-Man faces off against Doctor Octopus and loses the fight, his morale diminishes quickly. Similarly, the United States’ dominance over the USSR, particularly on the matter of technological development, was precarious.120 While the need for rapid development and military spending was apparent, many scientists saw the arms race as an ultimately toxic endeavor.121

The pressing question was whether the USA would survive the arms race with the USSR. These anxieties, among other things, manifest in Spider-Man’s vague “spider sense,” a sixth sense that warns him of impending danger. Doctor Octopus can be seen as an allegory for the arms race between the USA and the USSR. Started as a means of improving the state of science in the world and gaining the respect and fear of other scientists, the arms fuse onto the doctor, representative of the nation’s dependency on the booming military-industrial complex and the attachment of American ideals to the competition with the USSR.

The first several issues of Amazing Spider-Man painted a character vastly different from Captain America. Focused on self-improvement and preoccupied with supporting his aging aunt, Spider-Man seems to have no higher purpose. Unlike Captain America, Spider-Man is often shown in his weakest moments, after the death of his uncle and when his girlfriend is later kidnapped. He serves as a relatable and fallible character, and as such his actions are not driven by a higher morality. Spider-Man represented a new breed of superhero, one that managed to balance mundane duties with the additional responsibility of saving lives.

In the Golden Age, comics were extraordinarily optimistic, with Captain America glorifying the war effort and instilling a nationalistic fervor. However, during the Silver Age,

comic books were forced to restrict their content due to the self-imposed Comics Code Authority, but themes of alienation and fear of technology still informed the narratives and superheroes. Spider-Man epitomized these themes, receiving his superpowers from the mystical properties of radiation and battling villains who had set out to push the frontiers of science but went astray with their newfound power.

The apparent differences between Captain America and Spider-Man were contemporaneous with shifting popular sentiment regarding the development of the United States as a global power. Captain America epitomized an ideal form of the United States as it acted on the world stage, and people responded well to the United States actively propagating and establishing democracy in foreign nations. However, in less than a decade, prevailing opinion shifted to one of caution and confusion amidst the brewing Cold War with the Soviet Union. Spider-Man debuted as a fallible and relatable character who fought technological inventions that went awry. The parallel changes in idealized heroes and public opinion regarding American military and foreign policy suggest that comic books provide insight into the issues that concerned the readership. As a cheaply produced and widely available medium, comic books help a wide variety of readers interact with current events as they occur, serving as a unique and honest barometer of swiftly shifting opinions.

Notes

1 Sanderson Vanderbilt, "The Comics," Yank, the Army Weekly, November 23, 1945, 8, Sanderson Vanderbilt, "The Comics," Yank, the Army Weekly, November 23, 1945, [Page #], accessed March 30, 2016, http://www.unz.org/Pub/Yank-1945nov2300008?View=PDF.accessed March 30, 2016.

2 Ibid.

3 Jean-Paul Gabilliet, Of Comics and Men: A Cultural History of American Comic Books, trans. Bart Beaty and Nick Nguyen (Jackson, USA: University Press of Mississippi, 2010), 13, originally published as Des Comics et des hommes: Histoire culturelle des comic books aux Etats-Unis (Paris: Editions du Temps, 2005).

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 Richard Reynolds, "Masked Heroes," in Superhero Reader, ed. Charles Hatfield, Jeet Heer, and Kent Worcester (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2013), 100, previously published in Super Heroes: A Modern Mythology (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1994), 7-25.

7 Ibid.

8 Vanderbilt, "The Comics," 8.

9 Reynolds, "Masked Heroes," in Superhero Reader, 100.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid., 101.

14 Christian Russell, Heroic Moments: A Study of Comic Book Superheroes in RealWorld Society, 124, accessed March 30, 2016.

15 Ibid.

16 Ibid.

17 Reynolds, "Masked Heroes," in Superhero Reader, 101.

18 Russell, Heroic Moments: A Study, 124.

19 Ibid.

20 Ibid.

21 Ibid.

22 Ibid.

23 Ibid.

24 Reynolds, "Masked Heroes," in Superhero Reader, 101.

25 Ibid.

26 David M. Kennedy, The American People in the Great Depression (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 399-401.

27 Ibid., 387-388.

28 Gabilliet, Of Comics and Men, 20.

29 Ibid.

30 Ibid.

31 Kennedy, Freedom from Fear: The American, 400.

32 Ibid.

33 William H. Chafe, The Unfinished Journey, 3rd ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995), 3.

34 Ibid.

35 Ibid., 4

36 Ibid.

37 Ibid.

38 James T. Patterson, Grand Expectations (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), 8.

39 Chafe, The Unfinished Journey, 4-5.

40 Ibid., 48.

41 Randy Duncan and Matthew J. Smith, Icons of the American Comic Book: From Captain America to Wonder Woman (Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2013), 1:193.

42 Ibid., 195.

43 Ibid.

44 Ibid., 196

45 Ibid., 199.

46 Chafe, The Unfinished Journey, 67.

47 Ibid.

48 Duncan and Smith, Icons of the American, 1:193-201.

49 Ibid.

50 Ibid.

51 Jack Kirby and Joe Simon, comic strip, Captain America Comics #1, March 1, 1941, 1, accessed August 25, 2015, http://marvel.com/comics/issue/7849/captain_america_comics_1941_1.

52 Bradford W. Wright, Comic Book Nation (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003), 36.

53 Ibid.

54 Ibid.

55 Jason Dittmer, "Captain America's Empire: Reflections on Identity, Popular Culture, and Post-9/11 Geopolitics,"Annals of the Association of American Geographers 95, no. 3 (September 2005): 629, accessed September 18, 2015, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3693960.

56 Ibid.

57 Ibid.

58 Al Avison, Don Rico, and Stan Lee, comic strip, Captain America Comics #13, April 1, 1942, 1, accessed April 1, 2016, http://marvel.com/comics/issue/7853/captain_america_comics_1941_13.

59 Chafe, The Unfinished Journey, 10.

60 Ibid.

61 Dittmer, "Captain America's Empire: Reflections," 630.

62 Ibid.

63 Ibid.

64 Ibid.

65 Ibid.

66 Ibid.

67 Jack Kirby and Joe Simon, comic strip, Captain America Comics #2, April 1, 1941, 1, accessed August 25, 2015, http://marvel.com/comics/issue/7849/captain_america_comics_1941_1.

68 James T. Patterson, Grand Expectations (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), 8.

69 Hannah Miles, "WWII Propaganda: The Influence of Racism," Artifacts, no. 6 (March 2012): 1, accessed April 6, 2016, https://artifactsjournal.missouri.edu/2012/03/wwii-propagandathe-influence-of-racism/.

70 Ibid.

71 Ibid.

72 Patterson, Grand Expectations, 6.

73 Ibid., 7.

74 Ibid.

75 Ibid., 18.

76 Dittmer, "Captain America's Empire: Reflections," 627.

77 Reynolds, "Masked Heroes," in Superhero Reader, 101.

78 Gabilliet, Of Comics and Men, 53.

79 Ibid.

80 Patterson, Grand Expectations, 167.

81 Ibid., 127.

82 Reynolds, "Masked Heroes," in Superhero Reader, 101.

83 Ibid., 172.

84 Ibid.

85 Ibid., 196.

86 Duncan and Smith, Icons of the American, 1:201.

87 Stan Lee, Steve Ditko, and Johnny Dee, comic strip, Amazing Spider-Man #2, March 10, 1963, 1, accessed August 25, 2015, http://marvel.com/comics/issue/6482/amazing_spiderman_1963_1.

88 James T. Patterson, Grand Expectations (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), 204.

89 Patterson, Grand Expectations, 181.

90 Ibid., 133.

91 Ibid., 180.

92 Gabilliet, Of Comics and Men, 24.

93 Russell, Heroic Moments: A Study, 125.

94 Patterson, Grand Expectations, 384.

95 Russell, Heroic Moments: A Study, 125.

96 Ibid.

97 Ibid.

98 Ibid.

99 Ibid.

100 Patterson, Grand Expectations, 173.

101 Ibid.

102 Russell, Heroic Moments: A Study, 123.

103 Ibid.

104 Stan Lee, Steve Ditko, and Johnny Dee, comic strip, Amazing Spider-Man #1, March 10, 1963, 24, accessed August 25, 2015, http://marvel.com/comics/issue/6482/amazing_spiderman_1963_1.

105 Russell, Heroic Moments: A Study, 124.

106 Gabilliet, Of Comics and Men, 47.

107 Lee, Ditko, and Dee, comic strip, 1.

108 Bradford W. Wright, Comic Book Nation (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003), 276.

109 Ibid.

110 Ibid., 277.

111 Patterson, Grand Expectations, 338.

112 Lee, Ditko, and Dee, comic strip, 1.

113 Ibid.

114 Patterson, Grand Expectations, 178.

115 Ibid., 173.

116 Ibid.

117 Ibid.

118 Lee, Ditko, and Dee, comic strip, 13.

119 Patterson, Grand Expectations, 177.

120Ibid., 175.

121 Ibid.

Biliography

Avison, Al, Don Rico, and Stan Lee. Comic strip. Captain America Comics #13, April 1, 1942. Accessed April 1, 2016.

http://marvel.com/comics/issue/7853/captain_america_comics_1941_13.

Chafe, William H. The Unfinished Journey. 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995.

Costello, Matthew J. Secret Identity Crisis: Comic Books and the Unmasking of Cold War America. New York, NY: Continuum, 2009.

Dittmer, Jason. “Captain America’s Empire: Reflections on Identity, Popular Culture, and Post9/11 Geopolitics.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 95, no. 3 (September 2005): 626-43. Accessed September 18, 2015. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3693960.

Duncan, Randy, and Matthew J. Smith. Icons of the American Comic Book: From Captain America to Wonder Woman. Vol. 1. Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2013.

Gabilliet, Jean-Paul. Of Comics and Men: A Cultural History of American Comic Books. Translated by Bart Beaty and Nick Nguyen. Jackson, USA: University Press of Mississippi, 2010. Originally published as Des Comics et des hommes: Histoire culturelle des comic books aux Etats-Unis (Paris: Editions du Temps, 2005).

Kennedy, David M. Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 19291945. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Kirby, Jack, and Joe Simon. Comic strip. Captain America Comics #1, March 1, 1941. Accessed August 25, 2015. http://marvel.com/comics/issue/7849/captain_america_comics_1941_1.

Comic strip. Captain America Comics #2, April 1, 1941. Accessed August 25, 2015. http://marvel.com/comics/issue/7849/captain_america_comics_1941_1.

Lee, Stan, Steve Ditko, and Johnny Dee. Comic strip. Amazing Spider-Man #1, March 10, 1963. Accessed August 25, 2015. http://marvel.com/comics/issue/6482/amazing_spiderman_1963_1.

Comic strip. Amazing Spider-Man #2, March 10, 1963. Accessed August 25, 2015. http://marvel.com/comics/issue/6482/amazing_spider-man_1963_1.

Miles, Hannah. “WWII Propaganda: The Influence of Racism.” Artifacts, no. 6 (March 2012). Accessed April 6, 2016. https://artifactsjournal.missouri.edu/2012/03/wwii-propagandathe-influence-of-racism/.

Patterson, James T. Grand Expectations. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Reynolds, Richard. “Masked Heroes.” In Superhero Reader, edited by Charles Hatfield, Jeet Heer, and Kent Worcester. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2013. Previously published in Super Heroes: A Modern Mythology. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1994. 7-25.

Russell, Christian. Heroic Moments: A Study of Comic Book Superheroes in Real-World Society. Accessed March 30, 2016.

Szasz, Ferenc Morton. Atomic Comics: Cartoonist Confront the Nuclear World. Reno: University of Nevada Press, 2012.

Vanderbilt, Sanderson. “The Comics.” Yank, the Army Weekly, November 23, 1945, 8-9. Accessed March 30, 2016. http://www.unz.org/Pub/Yank-1945nov23-00008?View=PDF.

Wright, Bradford W. Comic Book Nation. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003.